Prospects for a Megacity Region Transition in Australia: A Preliminary Examination of Transport and Communication Drivers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Whether introduction of ‘fast rail’, connecting Melbourne with regional cities at operating speeds of less than 100 km/h, provided sufficient savings in travel times to stimulate population and employment growth in the non-metropolitan centres.

- Whether introduction of broadband services across Victoria at different operating speeds ranging from 12 Mbps to 1000 Mbps has been associated with uniform rates of take-up in metropolitan compared to regional centres.

- Whether positive population and employment impacts associated with the introduction of HSR (>200 km/h) for intercity rail corridors in SE England represent an analogue for future HSR projects linking Melbourne and its regional cities.

2. Background

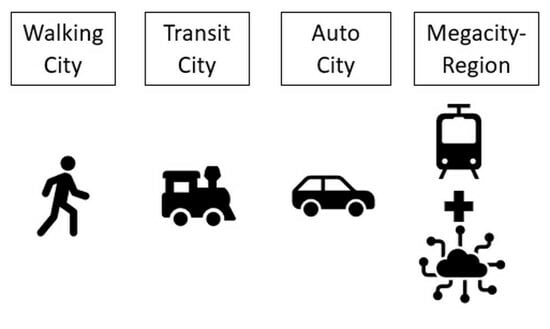

2.1. Industrial Transitions

2.2. Technology Transitions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Spatial Context

3.1.1. Business as Usual: Melbourne and the Regions

3.1.2. Melbourne Megacity Region

3.2. Proposed Analytics

3.2.1. Regional Fast Rail

3.2.2. Broadband

3.2.3. High-Speed Rail (UK)

4. Analyses and Results

4.1. Exploring the Impacts of Regional Fast Rail on Regional Population and Employment Growth in Victoria

4.2. Broadband Uptake: An Indicator of Telecommuting Capacity, Human Capital, Industry Structure Potential?

4.3. Assessing Impact of HSR in Southeast England: An Analogue for Selected Corridors in Victoria?

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bureau of Infrastructure Transport and Regional Economics. The Evolution of Australian Towns; Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development: Canberra, Australia, 2014.

- Centre for Population. Regional Population, 2022–23; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2024.

- Committee for Melbourne. Benchmarking Melbourne 2024; Committee for Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, J.; Houghton, K.; Vonthethoff, B. Regional Population Growth—Are We Ready? The Economics of Alternative Australian Settlement Patterns; The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Future Earth Australia. 2023 Update: Sustainable Cities and Regions. 10-Year Strategy to Enable Urban Systems Transformation; Future Earth Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Future Earth Australia: The Australian Academy of Science. Sustainable Cities and Regions: 10 Year Strategy to Enable Urban Systems Transformation; Future Earth Australia: The Australian Academy of Science: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of Australia. Building Up & Moving Out. Inquiry into the Australian Government’s Role in the Development of Cities; House of Representatives Standing Committee on Infrastructure, Transport and Cities, Ed.; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Planning Institute of Australia [PIA]. Through the Lens: The Tipping Point; Planning Institute of Australia [PIA]: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- SGS Economics & Planning. Reimagining Australia’s South-East: Prepared for the Committee for Melbourne; SGS Economics & Planning: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Regional Australia Institute. The Future of Work: Setting Kids up for Success; Regional Australia Institute: Canberra, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Regional Cities Victoria [RCV]. Growing our Regions, Growing Victoria: RCV Strategic Priorities 2017–2018; Regional Cities Victoria [RCV]: Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, A.; Castree, N.; Kitchin, R. A Dictionary of Human Geography; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS]. Population Projections Australia, 2017 to 2066; Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS]: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Levin, I.; Nygaard, C.; Gifford, S.; Newton, P. (Eds.) Migration and Urban Transitions in Australia; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government. Intergenerational Report 2023: Australia’s Future to 2063; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2023.

- Center for Population. 2022 Population Statement; Center for Population: Canberra, Australia, 2022.

- Hare, J.; Kehoe, J. Australia has reached ‘peak migration’. Australian Financial Review, 24 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS]. 3101.0—Australian Demographic Statistics, June 2018; Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS]: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Australian Government. The State of Australia’s Environment. Available online: https://soe.dcceew.gov.au/ (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Victorian Government. Victoria in Future 2019. Population Projections 2016 to 2056; Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning: Melbourne, Australia, 2019.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS]. Census DataPacks. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/datapacks?release=2021&product=TSP&geography=ALL&header=S (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Newton, P. Liveable and Sustainable? Socio-Technical Challenges for Twenty-First-Century Cities. J. Urban Technol. 2012, 19, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, P.; Glackin, S. Understanding Infill: Towards New Policy and Practice for Urban Regeneration in the Established Suburbs of Australia’s Cities. Urban Policy Res. 2014, 32, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, P.; Newman, P.; Glackin, S.; Thomson, G. Greening the Greyfields: New Models for Regenerating the Middle Suburbs of Low-Density Cities; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- SGS Economics & Planning. Economic Performance of Australia’s Cities and Regions, 2018–2019; SGS Economics & Planning: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S.; Bucifal, S.; Drake, P.; Hendrickson, L. Australian Geography of Innovative Entrepreneurship. Research Paper 3/2015; Department of Industry and Science: Canberra, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bolleter, J.; Freestone, R. Planning for a Continent of Cities: Long-Range Scenarios for Australian Urbanisation; SGS Economics & Planning: Perth, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo, G. Is decentralisation the answer? In Productivity Commission, A ‘Sustainable’ Population? In Key Policy Issues, Roundtable Proceedings; Productivity Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2011; pp. 133–170. [Google Scholar]

- Bolleter, J. The Ghost Cities of Australia: A Survey of New City Proposals and Their Lessons for Australia’s 21st Century Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Piko, L.; Taylor, E.; Horne, R. Balance Victoria: Prospects for Decentralisation; Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Planning for Australia’s Population Future; Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

- Albanese, A. Meeting of National Cabinet—Working Together to Deliver Better Housing Outcomes; Office of the Australian Prime Minister: Canberra, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Victorian Government. A Long Term Housing Plan. Available online: https://www.vic.gov.au/long-term-housing-plan (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Godde, C. Bitter blow’: Geelong to Melbourne fast-rail link axed. The Canberra Times, 16 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kolovos, B. Victoria announces first large Suburban Rail Loop contract amid ‘excessive secrecy’ concerns. The Guardian, 12 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P.; Pain, K. The Polycentric Metropolis: Learning from Mega-City Regions in Europe; Easthscan: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P.J.; Ni, P.; Derudder, B.; Hayler, M.; Huang, J.; Witlox, F. Global Urban Analysis A Survey of Cities in Globalization; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.-F.; Donegan, P.; Chisholm, C.; Oberklaid, M. Mapping Australia’s Economy: Cities as Engines of Prosperity; Grattan Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD]. Regions and Cities at a Glance 2018—AUSTRALIA; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gipps, P.; Brotchie, J.; Henshaw, D.; Newton, P.; O’Connor, K. The Journey to Work: Employment and the Changing Structure of Australian Cities; Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. The Global City: New York, Tokyo, London; Princeton University Press: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.J. Global City-Regions: Trends, Theory, Policy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Glaeser, E.L. Triumph of the City; Penguin Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. The Changing Geography of America’s Creative Class. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-08-27/the-changing-geography-of-america-s-creative-class?embedded-checkout=true (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Donegan, M.; Drucker, J.; Goldstein, H.; Lowe, N.; Malizia, E. Which Indicators Explain Metropolitan Economic Performance Best? Traditional or Creative Class. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2008, 74, 80–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratchett, L.; Hu, R.; Walsh, M.; Tuli, S. The Knowledge City Index: A Tale of 25 Cities in Australia; The neXus Research Centre, Faculty of Business, Government and Law: Canberra, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, A. Regional Australia Is Calling the Shots Now More than Ever. Available online: https://theconversation.com/regional-australia-is-calling-the-shots-now-more-than-ever-110432 (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- Regional Australia Institute. [In]Sights for Competitive Regions: Demography; Regional Australia Institute: Canberra, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, G.; Newton, P.; Newman, P. Urban Regeneration and Urban Fabrics in Australian Cities. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2017, 10, 169–190. [Google Scholar]

- Laird, P. Can the New High Speed Rail Authority Deliver after 4 Decades of Costly Studies? Available online: https://theconversation.com/can-the-new-high-speed-rail-authority-deliver-after-4-decades-of-costly-studies-206287 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Newton, P. Delays at Canberra: Why Australia Should Have Built Fast Rail Decades Ago. Available online: https://theconversation.com/delays-at-canberra-why-australia-should-have-built-fast-rail-decades-ago-57733 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Newton, P. Telematic Underpinnings of the Information Economy. In Cities of the 21st Century: New Technologies and Spatial Systems; Brotchie, J., Batty, M., Hall, P., Newton, P., Eds.; Longman Cheshire: Melbourne, Australia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, P. Changing Places? Households, Firms and Urban Hierarchies in the Information Age. In Cities in Competition: Productive and Sustainable Cities for the 21st Century; Brotchie, J., Batty, M., Blakely, E., Hall, P., Newton, P., Eds.; Longman Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, T.; Currie, G.; Aston, L. COVID and working from home: Long-term impacts and psycho-social determinants. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2022, 156, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moglia, M.; Glackin, S.; Hopkins, J.L. The Working-from-Home Natural Experiment in Sydney, Australia: A Theory of Planned Behaviour Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PWC. 2023 Future of Work Outlook. Available online: https://www.pwc.com.au/important-problems/future-of-work/2023-Future-of-Work-Outlook.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Denham, T. The limits of telecommuting: Policy challenges of counterurbanisation as a pandemic response. Geogr. Res. 2021, 59, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.; Sinha, S.; Flanagan, A. A Review of the State of Impact Evaluation; Independent Evaluation Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bolleter, J.; Edwards, N.; Freestone, R.; Nichols, D.; Hooper, P. Evaluating scenarios for twenty-first century Australian settlement planning: A Delphi study with planning experts. Int. Plan. Stud. 2022, 27, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infrastructure Victoria. Choosing Victoria’s Future. 5 Development Scenarios. Available online: https://www.infrastructurevictoria.com.au/project/choosing-victorias-future/ (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Department of the Treasury. Working Future: The Australian Government’s White Paper on Jobs and Opportunities; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2023.

- Australian Railway Association and ARUP. Faster Rail Report. Bringing Australia’s Rail Network Up to Speed; ARA and ARUP: Canberra, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD]. Redefining Urban: A New Way to Measure Metropolitan Areas; OECD: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, C. Anthropological invariants in travel behavior. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 1994, 47, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeckel, R. Working from Home: Modeling the Impact of Telework on Transportation and Land Use. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 26, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, J.; Wenner, F.; Thierstein, A. Working From Home and COVID-19: Where Could Residents Move to? Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, E.O.; Santiago, M.Q.; Pastor, I.O. Road and Railway Accessibility Atlas of Spain. J. Maps 2011, 7, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitten, J. The influence of Melbourne-Sydney intercity high-speed rail on spatial accessibility: An analysis of current proposals. In Proceedings of the 9th State of Australian Cities Conference, Perth, Australia, 30 November–5 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- de Silva, H.; Lightfoot, A. Commuting to work by private vehicle in Melbourne: Trends and policy implications. In Proceedings of the Australasian Transport Research Forum, Canberra, Australia, 29 September–1 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Victoria State Government. Plan Melbourne 2017–2050; Victoria State Government: Melbourne, Australia, 2017.

- Hall, P. Looking Backward, Looking Forward: The City Region of the Mid-21st Century, Regional Studies. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.; Hull, A. The Futures of the City Region. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glocker, D. The Rise of Megaregions: Delineating a New Scale of Economic Geography. CFE Working Paper; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yaro, R.; Zhang, M.; Steiner, F. Megaregions and America’s Future; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, P. Australian State of the Environment Report: Human Settlements Theme Commentary. Available online: https://webarchive.nla.gov.au/awa/20120319025906/http://www.environment.gov.au/soe/2006/publications/commentaries/settlements/index.html (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Committee for Sydney. The Sandstone Megaregion: Uniting Newcastle—Central Coast—Sydney—Wollongong; Committee for Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, P. Hyperconnected Regional Settlements Could Take Pressure off Melbourne and Sydney. Available online: https://www.thefifthestate.com.au/urbanism/planning/hyperconnected-regional-settlements-could-take-pressure-off-melbourne-and-sydney (accessed on 18 June 2020).

- High Speed Rail Authority, HRSA. Corporate Plan 2023–24 to 2026–27; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2023.

- Newton, P.; Brotchie, J.; Gipps, P. (Eds.) Cities in Transition: Changing Economic and Technological Processes and Australia’s Settlement System; Environment Australia: Canberra, Australia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brotchie, J.; Hall, P.; Newton, P. The Transition to an Information Society. In The Spatial Impact of Technological Change; Brotchie, J., Hall, P., Newton, P., Eds.; Methuen: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Newton, P.; Moglia, M.; Pineda-Pinto, M.; Prasad, D. (Eds.) Future City Making. Frontiers of Mission-Oriented Research for Urban Transitions; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, M. Mission-Oriented Research and Innovation in the European Union. A Problem-Solving Approach to Fuel Innovation-Led Growth; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, M. Mission Economy. A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism; Penguin: Sydney, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS]. Census DataPack for Urban Centres and Localities, Victoria, 2016; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2016.

- Office for National Statistics [ONS]. Estimates of the Population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland; Government of the United Kingdom: London, UK, 2020.

- Snape, J. Satellite, Fixed Wireless, Fibre and Mobile Broadband: Australia’s Internet Technologies Compared for You. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-01-16/fixed-wireless-fibre-satellite-nbn-explained/13046584 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- National Broadband Network [NBN]. Financial Reports. Available online: https://www.nbnco.com.au/corporate-information/about-nbn-co/corporate-plan/financial-reports (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Philbeck, T.; Davis, N. The Fourth Industrial Revolution: Shaping New Era. J. Int. Aff. 2018, 72, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS]. How ANZSCO Works; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2021.

- Preston, J.; Wall, G. The Ex-ante and Ex-post Economic and Social Impacts of the Introduction of High-speed Trains in South East England. Plan. Pract. Res. 2008, 23, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.; O’Donoghue, D. The Channel Tunnel: Transport patterns and regional impacts. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 31, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickerman, R. High-speed Rail and Regional Development: The Case of Intermediate Stations. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 42, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. Can Urban Congestion Really Be Solved with High Speed Rail? Available online: https://www.thefifthestate.com.au/columns/spinifex/can-urban-congestion-really-be-solved-with-high-speed-rail (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Buxton, M. This Is How Regional Rail Can Help Ease Our Big Cities’ Commuter Crush. Available online: https://theconversation.com/this-is-how-regional-rail-can-help-ease-our-big-cities-commuter-crush-81902 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Collins, J. The Regions Can Take More Migrants and Refugees, with a Little Help. Available online: https://theconversation.com/the-regions-can-take-more-migrants-and-refugees-with-a-little-help-121942 (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Denham, T.; Dodson, J. Regional Cities Beware—Fast Rail Might Lead to Disadvantaged Dormitories, Not Booming Economies. The Conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/regional-cities-beware-fast-rail-might-lead-to-disadvantaged-dormitories-not-booming-economies-119090 (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Searle, G. Making Small Cities Bigger Will Help Better Distribute Australia’s 25 Million People. Available online: https://theconversation.com/making-small-cities-bigger-will-help-better-distribute-australias-25-million-people-101180 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Terrill, M.; Moran, G.; Crowley, T. Fast Train Fever: Why Renovated Rail Might Work But Bullet Trains Wont; Grattan Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics [ONS]. Population Estimates for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: Mid-2017. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/releases/populationestimatesforukenglandandwalesscotlandandnorthernirelandmid2017 (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS]. Census of Population and Housing—Local Government Areas Time Series Profile, 2006; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2007.

- NOMIS. Annual Population Survey—Usual Resident Population by District, 2011 (KS101EW). Available online: https://www.nomisweb.co.uk/census/2011/ks101ew (accessed on 10 March 2019).

- NOMIS. Annual Population Survey—Industry of Employment by District, 2004 to 2018. Available online: https://www.nomisweb.co.uk/home/detailedstats.asp (accessed on 10 March 2019).

- Chen, C.; Hall, P. The Impacts of High-speed Trains on British Economic Geography: A study of the UK’s InterCity 125/225 and its Effects. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M. Inventing Future Cities; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nilles, J. Telecommunications-Transportation Tradeoff: Options for Tomorrow; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, P.; Wulff, M. Working at Home: Emerging Trends and Spatial Implications. In Houses and Jobs in Cities and Regions; O’Connor, K., Ed.; University of Queensland Press: Brisbane, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Global Workplace Analytics. Latest Work-At-Home, Telecommuting, Mobile Work and Remote Work Statistics. Available online: https://globalworkplaceanalytics.com/telecommuting-statistics (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Barraro, J.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S. Why Working from Home Will Stick; National Bureau of Economic Research: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, A. Has COVID Really Caused an Exodus from Our Cities? In Fact, Moving to the Regions Is Nothing New. Available online: https://theconversation.com/has-covid-really-caused-an-exodus-from-our-cities-in-fact-moving-to-the-regions-is-nothing-new-154724 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Real Insurance. The Real Australian Commute Report. Available online: https://www.realinsurance.com.au/documents/the-real-australian-commute-report-whitepaper.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Hargroves, K.; Smith, M. The Natural Advantage of Nations: Business Opportunities, Innovation and Governance in the 21st Century; Earthscan: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication; UNEP: Paris, Freance, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, P.; Newman, P. Critical Connections: The role of the built environment sector in delivering green cities and a green economy. Sustainability 2015, 7, 9417–9443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, P.; Prasad, D.; Sproul, A.; White, S. (Eds.) Decarbonising the Built Environment. Charting the Transition; Palgrave Macmillan, Springer Nature: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, D. Sydney’s New Industry Leading Automated Recycling Facility. Available online: https://thefifthestate.com.au/waste/sydneys-new-industry-leading-automated-recycling-facility (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Malik, A.; Li, M.; Lenzen, M.; Fry, J.; Liyanapathirana, N.; Beyer, K.; Boylan, S.; Lee, A.; Raubenheimer, D.; Geschke, A.; et al. Impacts of climate change and extreme weather on food supply chains cascade across sectors and regions in Australia. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, P.; Doherty, P. The challenges to urban sustainability and resilience. In Resilient Sustainable Cities: A Future; Newton, P., Pearson, L., Roberts, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Moonen, T. Mega Metropolitan Areas: Planning for Growth, Managing for the Future. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/sustainablecities/how-manage-urban-expansion-mega-metropolitan-areas (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Newton, P.; Frantzeskaki, N. Creating a National Urban Research and Development Platform for Advancing Urban Experimentation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, R.; Spiller, M. Australia’s Metropolitan Imperative. An Agenda for Governance Reform; CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Geography | Average Annual Growth (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2018–2036 (%) | 2021–2036 (%) | |

| Metropolitan Melbourne | ||

| Inner Melbourne LGAs | 2.4 | 2.7 |

| Established Melbourne LGAs | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Outer Metropolitan Growth Areas | 3.0 | 2.9 |

| Peri-urban LGAs | 1.8 | 2.7 |

| Non-metropolitan Regions | ||

| Regional City LGAs | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| Other Regional LGAs | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Region | Population 2021 * | Average Median Personal Income ($2021, ann.) * | Average Median Household Income ($2021, ann.) * | Ave House Price ($M) (2019) ** | Average Commute Distance ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner Melbourne | 1,141,000 | $55,800 | $106,000 | 1.154 | 9.5 |

| Outer Melbourne | 3,692,000 | $42,500 | $98,400 | 0.776 | 17.2 |

| Principal regional cities | 695,000 | $38,300 | $74,800 | 0.344 | 15.9 |

| Anchor City/ Destination City | 2021 Population | Max. Speed (km/h) | Date Opened |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melbourne to: | 4,833,000 | - | - |

| Geelong | 271,000 | 160 | September 2006 |

| Ballarat | 113,800 | 160 | December 2005 |

| Bendigo | 121,500 | 160 | February 2006 |

| Shepparton | 68,400 | 100–130 | N.A. |

| Wodonga | 43,300 | 100 | N.A. |

| Latrobe | 77,300 | 160 | October 2006 |

| London to: | 8,800,000 | - | - |

| Birmingham | 1,145,000 | 200 | December 2005 |

| Ashford | 133,000 | 230 | June 2009 |

| LGA Name | Dist. to Melb. | Total Employment | Employment in Producer Service Sectors * | Employment in People Serving Sectors * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (km) | 2021 | Avg Ann. Growth 2006–2021 | 2021 | Avg Ann. Growth 2006–2021 | 2021 | Avg Ann. Growth 2006–2021 | |

| Hume | 31 | 102,892 | 3.5 | 13,393 | 4 | 44,787 | 4.3 |

| Melton | 34 | 81,442 | 5.4 | 11,300 | 5.5 | 35,837 | 6.3 |

| Whittlesea | 35 | 107,055 | 4.5 | 14,700 | 5 | 49,969 | 5.7 |

| Wyndham | 36 | 135,825 | 6.4 | 26,213 | 8.1 | 57,772 | 6.8 |

| Greater Geelong | 60 | 129,587 | 2.8 | 16,510 | 3.2 | 69,792 | 3.4 |

| Macedon Ranges | 75 | 25,279 | 2.2 | 3881 | 3.1 | 11,473 | 2.4 |

| Moorabool | 79 | 18,429 | 3 | 2030 | 3.1 | 8230 | 3.6 |

| Mitchell | 85 | 23,504 | 3.6 | 2152 | 4.3 | 10,598 | 3.5 |

| Surf Coast | 109 | 18,769 | 4.1 | 2841 | 6 | 9719 | 4.4 |

| Ballarat | 119 | 53,104 | 2.3 | 5934 | 1.8 | 30,150 | 2.8 |

| Mount Alexander | 123 | 8570 | 1.6 | 1092 | 3.8 | 4480 | 2.1 |

| Hepburn | 129 | 7159 | 1.5 | 979 | 3.5 | 3522 | 1.7 |

| Baw Baw | 132 | 26,602 | 3.1 | 2638 | 3.6 | 12,198 | 3.8 |

| Strathbogie | 140 | 4925 | 1.3 | 447 | 2.6 | 2083 | 2.3 |

| Greater Bendigo | 142 | 56,299 | 2.1 | 6367 | 1.7 | 29,878 | 2.5 |

| Latrobe | 155 | 32,139 | 0.8 | 2849 | 0 | 16,608 | 1.4 |

| Golden Plains | 157 | 12,341 | 3.3 | 1177 | 3.6 | 5556 | 4.1 |

| Colac-Otway | 163 | 10,642 | 0.9 | 939 | 0.6 | 4614 | 0.9 |

| Pyrenees | 166 | 3032 | 1.2 | 196 | 1.4 | 1234 | 2.2 |

| Central Goldfields | 171 | 4693 | 0.9 | 319 | 0.2 | 2369 | 1.8 |

| Campaspe | 179 | 17,368 | 0.6 | 1260 | 0.6 | 7741 | 1.3 |

| Corangamite | 185 | 7583 | 0.1 | 455 | 1.2 | 2710 | 0.7 |

| Greater Shepparton | 200 | 30,136 | 1.1 | 2672 | 0.4 | 14,169 | 1.7 |

| Loddon | 209 | 3085 | −0.2 | 159 | 0.4 | 1030 | 0.4 |

| Benalla | 215 | 6251 | 0.4 | 507 | 1.2 | 2861 | 0.2 |

| Wellington | 220 | 19,315 | 0.8 | 1367 | 0.4 | 9582 | 1.3 |

| Ararat | 223 | 4973 | 0.4 | 275 | 0.6 | 2445 | 0.9 |

| Wangaratta | 240 | 14,043 | 0.8 | 1227 | 1.2 | 7293 | 1.4 |

| Moyne | 243 | 8539 | 1 | 605 | 2.5 | 3473 | 1.8 |

| Warrnambool | 260 | 17,305 | 1.5 | 1576 | 0.8 | 9750 | 1.9 |

| Gannawarra | 288 | 4391 | −0.7 | 269 | −0.4 | 1731 | 0.1 |

| Indigo | 291 | 8366 | 1.2 | 710 | 2.2 | 4068 | 1.4 |

| Wodonga | 303 | 20,689 | 1.7 | 1777 | −0.2 | 11,496 | 2.3 |

| East Gippsland | 376 | 19,190 | 1.3 | 1501 | 1.5 | 9829 | 1.5 |

| Swan Hill | 386 | 9866 | 0.5 | 707 | 0.4 | 3924 | 0.4 |

| Online LGA average | 108 | 41,501 | 2.4 | 4828 | 2.7 | 21,490 | 2.8 |

| Offline LGA average | 192 | 26,149 | 1.7 | 3368 | 2.1 | 3924 | 2.2 |

| Online LGA median | 119 | 26,602 | 2.3 | 2849 | 3,1 | 12,198 | 2.8 |

| Offline LGA median | 193 | 11,492 | 1.2 | 1078 | 1.2 | 4612 | 1.7 |

| 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 | 2020 | 2021 | 2021% Share Connections | 2021 Pop (‘000) | % Pop. Share | Ratio of NBN Connection to Pop. Share | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geelong | 0 | 636 | 6878 | 31,922 | 58,198 | 62,862 | 3.3 | 278 | 4.8 | 0.69 |

| Ballarat | 315 | 5571 | 19,972 | 29,820 | 36,996 | 38,466 | 2.0 | 157 | 2.6 | 0.81 |

| Bendigo | 0 | 368 | 903 | 26,330 | 36,409 | 38,174 | 2.0 | 152 | 2.6 | 0.81 |

| Shepparton | 0 | 1863 | 15,702 | 18,592 | 19,679 | 20,125 | 1.1 | 130 | 2.2 | 0.50 |

| Latrobe | 0 | 168 | 5293 | 21,064 | 22,183 | 22,735 | 1.2 | 271 | 4.6 | 0.28 |

| Albury Wodonga | 1 | 275 | 4539 | 33,125 | 35,652 | 36,917 | 2.0 | 286 | 4.8 | 0.42 |

| Melbourne | 2473 | 46,129 | 212,204 | 685,609 | 1,551,328 | 1,666,319 | 88.4 | 4714 | 78.4 | 1.12 |

| Total | 2789 | 55,010 | 265,491 | 846,462 | 1,760,445 | 1,885,598 | 100 | 6010 | 100 |

| Speed (Mbps) | Max TC4 12,25 | Max TC4 50,100 | Max TC4 250–1000 | Total Connections | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % Residential |

| Geelong | 17,292 | 4.8 | 44,917 | 3.2 | 653 | 0.6 | 62,862 | 85.6 |

| Ballarat | 9754 | 2.7 | 26,950 | 1.9 | 1762 | 1.7 | 38,466 | 84.2 |

| Bendigo | 9593 | 2.7 | 28,239 | 2.0 | 342 | 0.3 | 38,174 | 85.8 |

| Shepparton | 4545 | 1.3 | 14,423 | 1.0 | 1157 | 1.1 | 20,125 | 79.8 |

| Latrobe | 7700 | 2.1 | 14,872 | 1.0 | 163 | 0.2 | 22,735 | 86.6 |

| Albury-Wodonga | 9284 | 2.6 | 27,228 | 1.9 | 405 | 0.4 | 36,917 | 83.6 |

| Melbourne | 301,971 | 83.8 | 1,262,510 | 89.0 | 101,838 | 95.8 | 1,666,319 | 83.6 |

| Total | 360,139 | 100.0 | 1,419,139 | 1.0 | 106,320 | 1.0 | 1,885,598 | 83.7 |

| Speed (Mbps) | Max TC4 12,25 | Max TC4 50,100 | Max TC4 250–1000 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Geelong | 1623 | 3.9 | 7354 | 2.9 | 53 | 0.3 |

| Ballarat | 1142 | 2.7 | 4676 | 1.9 | 249 | 1.6 |

| Bendigo | 900 | 2.2 | 4507 | 1.8 | 25 | 0.2 |

| Shepparton | 748 | 1.8 | 2095 | 0.8 | 222 | 1.5 |

| Latrobe | 713 | 1.7 | 2311 | 0.9 | 13 | 0.1 |

| Albury-Wodonga | 1033 | 2.5 | 4973 | 2.0 | 39 | 0.3 |

| Melbourne | 35,531 | 85.2 | 223,801 | 89.6 | 14,578 | 96.0 |

| Total | 41,690 | 100.0 | 249,717 | 100.0 | 15,179 | 100.0 |

| City | Total Employed Persons 2021 | Total Full Time Employed Persons 2021 | High-Skilled Workforce 2021 | % Change: Total Employed 2011–2021 | % Change: Full Time Employed 2011–2021 | % Change: High-Skilled Workforce 2011–2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | ||||||

| Melbourne | 2,403,200 | 1,444,700 | 981,300 | 40.8 | 26.6 | 19.6 | 40.8 |

| Ballarat | 53,100 | 29,700 | 18,100 | 34.2 | 25.6 | 18.3 | 35.7 |

| Bendigo | 56,300 | 31,500 | 18,300 | 32.5 | 23.1 | 16.8 | 30.5 |

| Geelong | 129,600 | 72,000 | 44,300 | 34.2 | 35.8 | 27.6 | 55.8 |

| Latrobe | 32,100 | 18,000 | 8200 | 25.6 | 6.2 | 0.1 | 11.5 |

| Shepparton | 30,100 | 17,900 | 9600 | 31.8 | 13.1 | 8.7 | 13.7 |

| Wodonga | 20,700 | 12,500 | 5800 | 28.3 | 22.5 | 17.2 | 31.1 |

| LAD Name | Dist. to London | Total Employment | Employment in Producer Service Sectors (Cat. K–N) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (km) | 2006 | 2016 | % p.a. | 2005 | 2018 | % p.a. | |

| Barnet | 18 | 138,000 | 167,000 | 1.6 | 33,500 | 53,100 | 4.5 |

| Harrow | 22 | 83,000 | 89,000 | 0.6 | 20,800 | 31,800 | 4.1 |

| Barking and Dagenham | 23 | 51,000 | 64,000 | 2.0 | 9600 | 14,300 | 3.8 |

| Bexley | 24 | 73,000 | 88,000 | 1.6 | 20,200 | 21,500 | 0.5 |

| Hillingdon | 27 | 201,000 | 206,000 | 0.2 | 15,600 | 22,000 | 3.2 |

| Havering | 29 | 86,000 | 97,000 | 1.0 | 19,600 | 33,000 | 5.3 |

| Dartford | 39 | 53,000 | 70,000 | 3.2 | 5800 | 12,700 | 9.2 |

| Milton Keynes | 86 | 144,000 | 200,000 | 3.9 | 18,400 | 28,200 | 4.1 |

| Ashford | 96 | 56,000 | 70,000 | 2.5 | 8400 | 4900 | −3.2 |

| Kettering | 129 | 39,000 | 49,000 | 2.0 | 5100 | 5300 | 0.3 |

| Rugby | 138 | 48,000 | 53,000 | 1.0 | 4300 | 6300 | 3.6 |

| Coventry | 153 | 156,000 | 174,000 | 1.2 | 14,200 | 21,500 | 4.0 |

| Blaby | 159 | 50,000 | 59,000 | 1.4 | 6700 | 5000 | −2.0 |

| North Warwickshire | 171 | 38,000 | 50,000 | 2.4 | 2500 | 4000 | 4.6 |

| Solihull | 177 | 113,000 | 128,000 | 1.0 | 16,600 | 16,800 | 0.1 |

| Bromsgrove | 186 | 41,000 | 51,000 | 1.9 | 6400 | 7000 | 0.7 |

| Lichfield | 194 | 49,000 | 56,000 | 1.1 | 6500 | 7300 | 0.9 |

| Birmingham | 205 | 543,000 | 576,000 | 0.6 | 57,300 | 74,200 | 2.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Newton, P.; Whitten, J.; Glackin, S.; Reynolds, M.; Moglia, M. Prospects for a Megacity Region Transition in Australia: A Preliminary Examination of Transport and Communication Drivers. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16093712

Newton P, Whitten J, Glackin S, Reynolds M, Moglia M. Prospects for a Megacity Region Transition in Australia: A Preliminary Examination of Transport and Communication Drivers. Sustainability. 2024; 16(9):3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16093712

Chicago/Turabian StyleNewton, Peter, James Whitten, Stephen Glackin, Margaret Reynolds, and Magnus Moglia. 2024. "Prospects for a Megacity Region Transition in Australia: A Preliminary Examination of Transport and Communication Drivers" Sustainability 16, no. 9: 3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16093712