8q24.21 Locus: A Paradigm to Link Non-Coding RNAs, Genome Polymorphisms and Cancer

Abstract

:1. Introduction

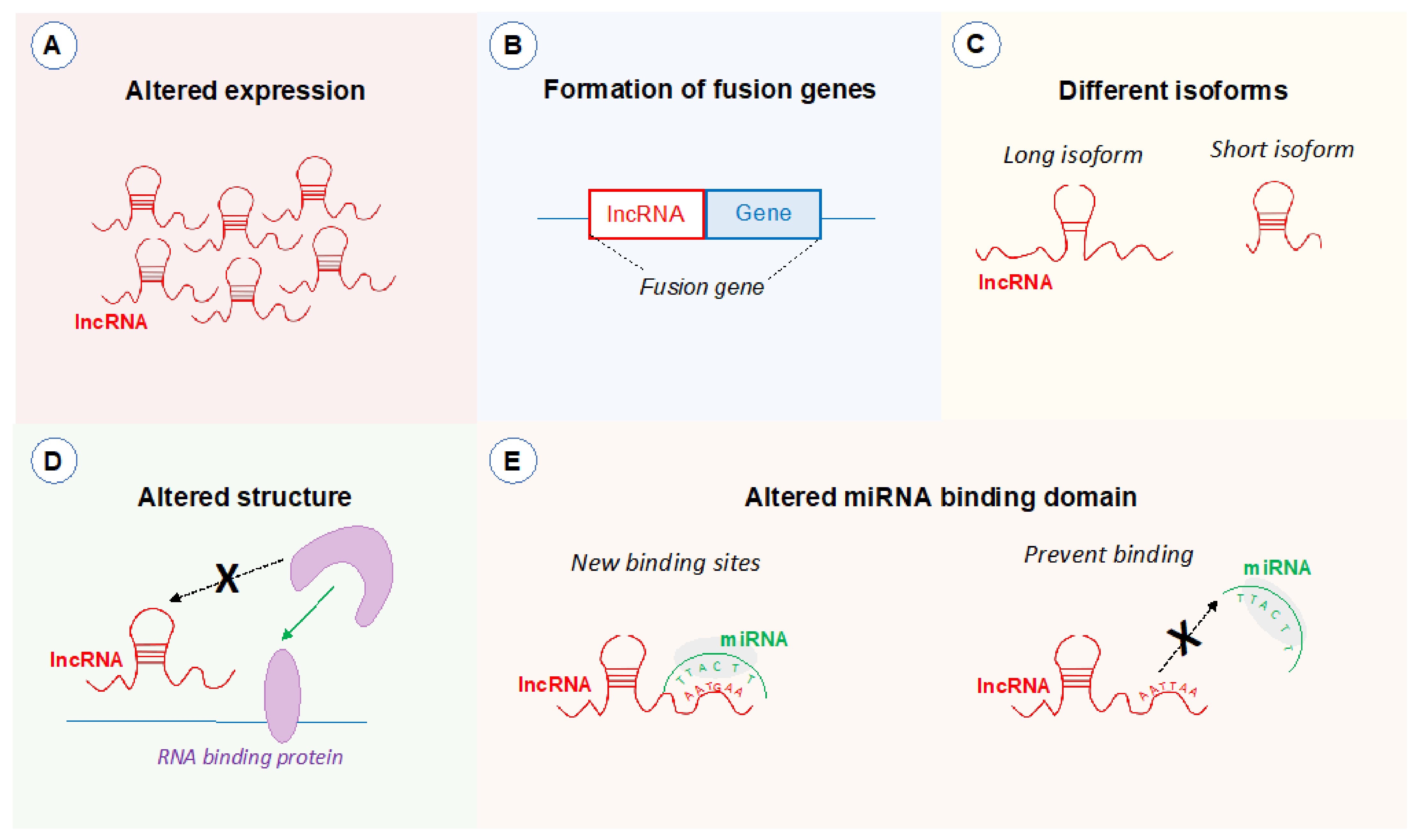

2. LncRNAs and Their Functions

3. LncRNAs, GWAS and Cancer

4. 8q24.21

4.1. 8q24.21 LncRNA Expression Changes in Cancer

4.2. 8q24.21 LncRNAs in miRNA Regulation

4.3. 8q24.21 LncRNAs and Chromatin Modifications

4.4. 8q24.21 LncRNAs and c-Myc Regulation

5. Potential Impact of Genetic Polymorphisms on 8q24.21 LncRNAs

5.1. Amplifications

5.2. Structural Variations

5.3. Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms

6. Future Work and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature 2004, 431, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giral, H.; Landmesser, U.; Kratzer, A. Into the Wild: GWAS Exploration of Non-coding RNAs. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, J.J.; Chang, H.Y. Unique features of long non-coding RNA biogenesis and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djebali, S.; Davis, C.A.; Merkel, A.; Dobin, A.; Lassmann, T.; Mortazavi, A.; Tanzer, A.; Lagarde, J.; Lin, W.; Schlesinger, F.; et al. Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature 2012, 489, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ma, L.; Bajic, V.B.; Zhang, Z. On the classification of long non-coding RNAs. RNA Biol. 2013, 10, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, R.-W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.-L. Cellular functions of long noncoding RNAs. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintacuda, G.; Young, A.N.; Cerase, A. Function by Structure: Spotlights on Xist Long Non-coding RNA. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2017, 4, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, K.C.; Chang, H.Y. Molecular mechanisms of long noncoding RNAs. Mol. Cell. 2011, 43, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, L.; Sun, K.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Lu, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, F.; Bao, X.; et al. Linc-YY1 promotes myogenic differentiation and muscle regeneration through an interaction with the transcription factor YY1. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohammad, F.; Mondal, T.; Guseva, N.; Pandey, G.K.; Kanduri, C. Kcnq1ot1 noncoding RNA mediates transcriptional gene silencing by interacting with Dnmt1. Development 2010, 137, 2493–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, K.C.; Yang, Y.W.; Liu, B.; Sanyal, A.; Corces-Zimmerman, R.; Chen, Y.; Lajoie, B.R.; Protacio, A.; Flynn, R.A.; Gupta, R.A.; et al. A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 472, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dimitrova, N.; Zamudio, J.R.; Jong, R.M.; Soukup, D.; Resnick, R.; Sarma, K.; Ward, A.J.; Raj, A.; Lee, J.T.; Sharp, P.A. Lin-cRNA-p21 activates p21 in cis to promote Polycomb target gene expression and to enforce the G1/S checkpoint. Mol. Cell. 2014, 54, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, X.; Haider, A.M.S.S.; Moran, M. The role of interactions of long non-coding RNAs and heterogeneous nuclear ribonu-cleoproteins in regulating cellular functions. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 2925–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shan, Y.; Ma, J.; Pan, Y.; Hu, J.; Liu, B.; Jia, L. LncRNA SNHG7 sponges miR-216b to promote proliferation and liver metastasis of colorectal cancer through upregulating GALNT1. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gong, C.; Maquat, L.E. lncRNAs transactivate STAU1-mediated mRNA decay by duplexing with 3’ UTRs via Alu elements. Nature 2011, 470, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tripathi, V.; Ellis, J.D.; Shen, Z.; Song, D.Y.; Pan, Q.; Watt, A.T.; Freier, S.M.; Bennett, C.F.; Sharma, A.; Bubulya, P.A.; et al. The Nuclear-Retained Noncoding RNA MALAT1 Regulates Alternative Splicing by Modulating SR Splicing Factor Phosphorylation. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoon, J.H.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Srikantan, S.; Yang, X.; Martindale, J.L.; De, S.; Huarte, M.; Zhan, M.; Becker, K.G.; Gorospe, M. Lin-cRNA-p21 suppresses target mRNA translation. Mol. Cell 2012, 47, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carrieri, C.; Cimatti, L.; Biagioli, M.; Beugnet, A.; Zucchelli, S.; Fedele, S.; Pesce, E.; Ferrer, I.; Collavin, L.; Santoro, C.; et al. Long non-coding antisense RNA controls Uchl1 translation through an embedded SINEB2 repeat. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 491, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.T. Epigenetic Regulation by Long Noncoding RNAs. Science 2012, 338, 1435–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sud, A.; Kinnersley, B.; Houlston, R.S. Genome-wide association studies of cancer: Current insights and future perspectives. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 692–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.Y.; Muller, W.J. Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, a003236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmitt, A.M.; Chang, H.Y. Long Noncoding RNAs in Cancer Pathways. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deng, J.; Yang, M.; Jiang, R.; An, N.; Wang, X.; Liu, B. Long Non-Coding RNA HOTAIR Regulates the Proliferation, Self-Renewal Capacity, Tumor Formation and Migration of the Cancer Stem-Like Cell (CSC) Subpopulation Enriched from Breast Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pan, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhou, F.; Su, B.; Li, Y. DNA methylation profiles in cancer diagnosis and therapeutics. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanly, D.J.; Esteller, M.; Berdasco, M. Interplay between long non-coding RNAs and epigenetic machinery: Emerging targets in cancer? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 20170074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.A.; Shah, N.; Wang, K.C.; Kim, J.; Horlings, H.M.; Wong, D.J.; Tsai, M.-C.; Hung, T.; Argani, P.; Rinn, J.L.; et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 464, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppi, K.; Pitt, J.J.; Wahlberg, B.M.; Caplen, N.J. The 8q24 Gene Desert: An Oasis of Non-Coding Transcriptional Activity. Front. Genet. 2012, 3, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dang, C.V.; O’Donnell, K.A.; Zeller, K.I.; Nguyen, T.; Osthus, R.C.; Li, F. The c-Myc target gene network. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2006, 16, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisanzio, C.; Freedman, M.L. Chromosome 8q24-Associated Cancers and MYC. Genes Cancer 2010, 1, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Lin, X.; Kapoor, A.; Chow, M.J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, K.; Tang, D. The Oncogenic Potential of the Centromeric Border Protein FAM84B of the 8q24.21 Gene Desert. Genes 2020, 11, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wei, J.; Xu, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Zeng, S.; Qian, L.; Yang, X.; Ou, C.; Lin, W.; Gong, Z.; et al. Overexpression of GSDMC is a prognostic factor for predicting a poor outcome in lung adenocarcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 21, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chattaragada, M.S.; Riganti, C.; Sassoe, M.; Principe, M.; Santamorena, M.M.; Roux, C.; Curcio, C.; Evangelista, A.; Allavena, P.; Salvia, R.; et al. FAM49B, a novel regulator of mitochondrial function and integrity that sup-presses tumor metastasis. Oncogene 2018, 37, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Müller, T.; Stein, U.; Poletti, A.; Garzia, L.; Rothley, M.; Plaumann, D.; Thiele, W.; Bauer, M.; Galasso, A.; Schlag, P.; et al. ASAP1 promotes tumor cell motility and invasiveness, stimulates metastasis formation in vivo, and correlates with poor survival in colorectal cancer patients. Oncogene 2010, 29, 2393–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hayashi, H.; Arao, T.; Togashi, Y.; Kato, H.; Fujita, Y.; De Velasco, M.A.; Kimura, H.; Matsumoto, K.; Tanaka, K.L.; Okamoto, I.; et al. The OCT4 pseudogene POU5F1B is amplified and promotes an aggressive phenotype in gastric cancer. Oncogene 2015, 34, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buniello, A.; MacArthur, J.A.L.; Cerezo, M.; Harris, L.W.; Hayhurst, J.; Malangone, C.; McMahon, A.; Morales, J.; Mountjoy, E.; Sollis, E.; et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D1005–D1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hrdlickova, B.; de Almeida, R.C.; Borek, Z.; Withoff, S. Genetic variation in the non-coding genome: Involvement of micro-RNAs and long non-coding RNAs in disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 1910–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mercer, T.R.; Dinger, M.E.; Mattick, J.S. Long non-coding RNAs: Insights into functions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huarte, M. The emerging role of lncRNAs in cancer. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1253–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Chen, Y.; Liao, X.; Liu, D.; Li, F.; Ruan, H.; Jia, W. Overexpression of long noncoding RNA PCAT-1 is a novel biomarker of poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. Med Oncol. 2013, 30, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.-H.; Yang, H.; Jiang, J.-H.; Lu, S.-W.; Peng, C.-X.; Que, H.-X.; Lu, W.-L.; Mao, J.-F. Prognostic significance of long non-coding RNA PCAT-1 expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 4126–4131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Wan, M.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Leng, K.; Kang, P.; Cui, Y.; Jiang, X. Long noncoding RNA PCAT1 regulates extrahepatic chol-angiocarcinoma progression via the Wnt/beta-catenin-signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017, 94, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.-H.; Wu, Q.-Q.; Li, S.-Q.; Yang, T.-X.; Liu, Z.-H.; Tong, Y.-S.; Tuo, L.; Wang, S.; Cao, X.-F. Upregulation of the long noncoding RNA PCAT-1 correlates with advanced clinical stage and poor prognosis in esophageal squamous carcinoma. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 2501–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarrafzadeh, S.; Geranpayeh, L.; Ghafouri-Fard, S. Expression Analysis of Long Non-Coding PCAT-1in Breast Cancer. Int. J. Hematol. Stem Cell Res. 2017, 11, 185–191. [Google Scholar]

- Sur, S.; Nakanishi, H.; Steele, R.; Ray, R.B. Depletion of PCAT-1 in head and neck cancer cells inhibits tumor growth and induces apoptosis by modulating c-Myc-AKT1-p38 MAPK signalling pathways. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, W.; Dong, N.; Huang, J.; Ye, B. Long non-coding RNA PCAT1 promotes cell migration and invasion in human laryngeal cancer by sponging miR-210-3p. J. BUON 2020, 24, 2429–2434. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, Y.; Ma, X. The lncRNA PCAT1 is correlated with poor prognosis and promotes cell proliferation, invasion, migration and EMT in osteosarcoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, Y.; Ge, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, G.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Chu, H. The association of rs710886 in lncRNA PCAT1 with bladder cancer risk in a Chinese population. Gene 2017, 627, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, Y.; Fu, C.; Wang, C.; Duan, X.; Zou, W.; Zhao, T. Knockdown of long non-coding RNA PCAT1 in glioma stem cells promotes radiation sensitivity. Med Mol. Morphol. 2018, 52, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.D.; Lu, J.; Lin, Y.S.; Gao, C.; Qi, F. Functional role of long non-coding RNA CASC19/miR-140-5p/CEMIP axis in colorectal cancer progression in vitro. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 1697–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Guo, R.X.; Han, L.P.; Gu, H.; Liu, M.Z. Effect of CASC19 on proliferation, apoptosis and radiation sensitivity of cervical cancer cells by regulating miR-449b-5p expression. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2020, 55, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Hu, T.; Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Cao, Y. Long non-coding RNA PRNCR1 modulates non-small cell lung cancer cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, invasion, and EMT through PRNCR1/miR-126-5p/MTDH axis. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20193153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Zou, Y.; Li, R.; Liu, D. Long noncoding RNA PRNCR1 exerts oncogenic effects in tongue squamous cell carcinoma in vitro and in vivo by sponging microRNA944 and thereby increasing HOXB5 expression. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 46, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- He, X.; Tan, X.; Wang, X.; Jin, H.; Liu, L.; Ma, L.; Yu, H.; Fan, Z. C-Myc-activated long noncoding RNA CCAT1 promotes colon cancer cell proliferation and invasion. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 12181–12188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treeck, O.; Skrzypczak, M.; Schüler-Toprak, S.; Weber, F.; Ortmann, O. Long non-coding RNA CCAT1 is overexpressed in endometrial cancer and regulates growth and transcriptome of endometrial adenocarcinoma cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2020, 122, 105740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ding, D.; Jiang, Z.; Du, T.; Liu, J.; Kong, Z. Long non-coding RNA CCAT1/miR-148a/PKCzeta prevents cell migration of prostate cancer by altering macrophage polarization. Prostate 2019, 79, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cao, Y.; Shi, H.; Ren, F.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, R. Long non-coding RNA CCAT1 promotes metastasis and poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Exp. Cell Res. 2017, 359, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, G.; Ma, Y.; Qu, H. lncRNA CCAT1 contributes to the growth and invasion of gastric cancer via targeting miR-219-1. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 19457–19468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, C.; Sun, L.; Jin, X.; Han, M.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, X.; Lv, J.; Li, T. Long non-coding RNA CARLo-5 promotes tumor progression in hepatocellular carcinoma via suppressing miR-200b expression. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 70172–70182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lai, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.; Ye, L. Down-regulation of LncRNA CCAT1 enhances radiosensitivity via regulating miR-148b in breast cancer. Cell Biol. Int. 2018, 42, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, Y. CCAT-1 promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of cervical cancer cells via the Wnt signaling pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 68059–68070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lv, L.; Jia, J.-Q.; Chen, J. The lncRNA CCAT1 Upregulates Proliferation and Invasion in Melanoma Cells via Suppressing miR-33a. Oncol. Res. Featur. Preclin. Clin. Cancer Ther. 2018, 26, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, K.; Wu, Q.; Jiang, S.; Yuan, H.; Huang, S.; Li, H. CCAT1 promotes laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma cell proliferation and invasion. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016, 8, 4338–4345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cui, B.; Li, B.; Liu, Q.; Cui, Y. lncRNA CCAT1 Promotes Glioma Tumorigenesis by Sponging miR-181b. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 118, 4548–4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunkumar, G.; Murugan, A.K.; Rao, H.P.S.; Subbiah, S.; Rajaraman, R.; Munirajan, A.K. Long non-coding RNA CCAT1 is overexpressed in oral squamous cell carcinomas and predicts poor prognosis. Biomed. Rep. 2017, 6, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, H.; Zhong, J.; Bian, Z.; Fang, X.; Peng, Y.; Hu, Y. Long non-coding RNA CCAT1 promotes human retinoblastoma SO-RB50 and Y79 cells through negative regulation of miR-218-5p. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 87, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.-Z.; Chu, B.-F.; Zhang, Y.; Weng, M.-Z.; Qin, Y.-Y.; Gong, W.; Quan, Z.-W. Long non-coding RNA CCAT1 promotes gallbladder cancer development via negative modulation of miRNA-218-5p. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, M.; Zhang, Q.; Tian, X.H.; Wang, J.L.; Niu, Y.X.; Li, G. lncRNA CCAT1 is a biomarker for the proliferation and drug resistance of esophageal cancer via the miR-143/PLK1/BUBR1 axis. Mol. Carcinog. 2019, 58, 2207–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadifard, M.; Pashaiefar, H.; Yaghmaie, M.; Montazeri, M.; Sadraie, M.; Momeny, M.; Jalili, M.; Ahmadvand, M.; Ghaffari, S.H.; Mohammadi, S.; et al. Expression Analysis of PVT1, CCDC26, and CCAT1 Long Noncoding RNAs in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomark. 2018, 22, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wei, H.; Li, L. LncRNA CCAT1/miR-130a-3p axis increases cisplatin resistance in non-small-cell lung cancer cell line by targeting SOX4. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2017, 18, 974–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Cheng, L. Long non-coding RNA CCAT1/miR-148a axis promotes osteosarcoma proliferation and migration through regulating PIK3IP1. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2017, 49, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Hao, S. LncRNA CCAT1 modulates the sensitivity of paclitaxel in nasopharynx cancers cells via miR-181a/CPEB2 axis. Cell Cycle 2017, 16, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, K.; Hua, L.; Wei, L.; Meng, J.; Hu, J. Correlation Between CASC8, SMAD7 Polymorphisms and the Susceptibility to Colo-rectal Cancer: An Updated Meta-Analysis Based on GWAS Results. Medicine 2015, 94, e1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, R.; Zhong, P.; Xiong, L.; Duan, L. Long Noncoding RNA Cancer Susceptibility Candidate 8 Suppresses the Proliferation of Bladder Cancer Cells via Regulating Glycolysis. DNA Cell Biol. 2017, 36, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.-H.; Chen, S.-H.; Lv, Q.-L.; Sun, B.; Qu, Q.; Qin, C.-Z.; Fan, L.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, L.; Zhou, H.-H. Clinical Significance of Long Non-Coding RNA CASC8 rs10505477 Polymorphism in Lung Cancer Susceptibility, Platinum-Based Chemotherapy Response, and Toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 545. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, E.R.; Hsieh, M.J.; Chiang, W.L.; Hsueh, K.C.; Yang, S.F.; Su, S.C. Association of lncRNA CCAT2 and CASC8 Gene Polymor-phisms with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ling, H.; Spizzo, R.; Atlasi, Y.; Nicoloso, M.; Shimizu, M.; Redis, R.S.; Nishida, N.; Gafà, R.; Song, J.; Guo, Z.; et al. CCAT2, a novel noncoding RNA mapping to 8q24, underlies metastatic progression and chromosomal instability in colon cancer. Genome Res. 2013, 23, 1446–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cai, Y.; Li, X.; Shen, P.; Zhang, D. CCAT2 is an oncogenic long non-coding RNA in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Biol. Res. 2018, 51, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yan, L.; Wu, X.; Yin, X.; Du, F.; Liu, Y.; Ding, X. LncRNA CCAT2 promoted osteosarcoma cell proliferation and invasion. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 2592–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, M.; Wang, L.; He, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Li, X. lncRNA CCAT2 promotes radiotherapy resistance for human esophageal carcinoma cells via the miR-145/p70S6K1 and p53 pathway. Int. J. Oncol. 2019, 56, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-J.; Zhu, J.-F.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, P.-P.; Zhang, J.-J. Upregulation of lncRNA CCAT2 predicts poor prognosis in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and is correlated with leukemic cell proliferation. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2018, 11, 5658–5666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Qiao, C.; Zong, L.; Chen, Y. Long non-coding RNA-CCAT2 promotes the occurrence of non-small cell lung cancer by regulating the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 4600–4606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qiu, M.; Xu, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Hu, J.; Xu, L.; Yin, R. CCAT2 is a lung adenocarcinoma-specific long non-coding RNA and promotes invasion of non-small cell lung cancer. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 5375–5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.-D.; Jiang, J.; Liu, M.-M.; Zhuang, R.-J.; Wang, H.; Li, P.-L. Silencing CCAT2 inhibited proliferation and invasion of epithelial ovarian carcinoma cells by regulating Wnt signaling pathway. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2017, 10, 11771–11778. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, P.; Cao, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Cui, Z. Knockdown of lncRNA CCAT2 inhibits endometrial cancer cells growth and metastasis via sponging miR-216b. Cancer Biomark. 2017, 21, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.J.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.Z.; Wang, Y.; Nian, W.Q.; Wang, L.L.; Li, L.C.; Luo, H.L.; Wang, D.L. Long non-coding RNA CCAT2 promotes the breast cancer growth and metastasis by regulating TGF-beta signaling pathway. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 706–714. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.L.; Liao, Y.; Qiu, M.X.; Li, J.; An, Y. Long non-coding RNA CCAT2 promotes cell proliferation and invasion through regulating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2017, 39, 1010428317711314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hua, F.; Li, C.-H.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.-P. Long Noncoding RNA CCAT2 Knockdown Suppresses Tumorous Progression by Sponging miR-424 in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Oncol. Res. 2018, 26, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.-L.; Shu, Y.-G.; Tao, M.-Y. LncRNA CCAT2 promotes angiogenesis in glioma through activation of VEGFA signalling by sponging miR-424. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2020, 468, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Liu, C.; Wang, C.; Ling, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, S.; Xu, B.; Guan, H.; et al. LncRNA CCAT1 Promotes Prostate Cancer Cell Proliferation by Interacting with DDX5 and MIR-28-5P. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 2469–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Lu, Y.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, W.; Li, X. Long non-coding RNA CASC11 interacts with hnRNP-K and activates the WNT/beta-catenin pathway to promote growth and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2016, 376, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, W.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, W. LncRNA CASC11 promotes the cervical cancer progression by activating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Biol. Res. 2019, 52, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Kang, W.; Lu, X.; Ma, S.; Dong, L.; Zou, B. LncRNA CASC11 promoted gastric cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion in vitro by regulating cell cycle pathway. Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 1886–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, H.; Xu, C.; Le, W.; Ge, B.; Wang, T. lncRNA CASC11 promotes cancer cell proliferation in bladder cancer through miR-NA-150. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 13487–13493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Nan, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yang, M.; Song, Q. LncRNA CASC11 promotes TGF-β1, increases cancer cell stemness and predicts postoperative survival in small cell lung cancer. Gene 2019, 704, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, R.; Jiang, Y.; Lai, B.; Lin, Y.; Wen, J. The positive feedback loop FOXO3/CASC11/miR-498 promotes the tumorigenesis of non-small cell lung cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 519, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.; Wu, J.; Yin, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Nie, Z.; Yin, J. LncRNA CASC11 promotes cancer cell proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting miRNA-188-5p. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20190251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, S.-G.; Wang, C.-H.; He, R.-Q.; Xu, R.-Y.; Ji, C.-B. LncRNA CASC11 promotes the development of esophageal carcinoma by regulating KLF6. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 8878–8887. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Han, J. Silencing CASC11 curbs neonatal neuroblastoma progression through modulating mi-croRNA-676-3p/nucleolar protein 4 like (NOL4L) axis. Pediatric Res. 2020, 87, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Feng, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y. Overexpression of CASC11 in ovarian squamous cell carcinoma mediates the development of cancer cell resistance to chemotherapy. Gene 2019, 710, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Yuan, X.; Li, G.; Ma, M.; Sun, J. Long noncoding RNA CASC11 promotes osteosarcoma metastasis by suppressing degradation of snail mRNA. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Zhang, S.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, C.; Feng, F. SP1 induced lncRNA CASC11 accelerates the glioma tumorigenesis through targeting FOXK1 via sponging miR-498. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 116, 108968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Z.; Xu, B.; He, L.; Zhang, G. PVT1 Promotes Angiogenesis by Regulating miR-29c/Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) Signaling Pathway in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 5418–5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Zhao, J.; He, Y. Long non-coding RNA PVT1 functions as an oncogene in human colon cancer through miR-30d-5p/RUNX2 axis. J. B.U.ON. Off. J. Balk. Union Oncol. 2018, 23, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Fang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Amplification of lncRNA PVT1 promotes ovarian cancer proliferation by binding to miR-140. Mamm. Genome 2019, 30, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Jin, J.; Han, G.; Sun, C.; Pizzi, M.P.; Huo, L.; Scott, A.; Wang, Y.; Ma, L.; et al. LncRNA PVT1 up-regulation is a poor prognosticator and serves as a therapeutic target in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Jing, Y.; Wei, F.; Tang, Y.; Yang, L.; Luo, J.; Yang, P.; Ni, Q.; Pang, J.; Liao, Q.; et al. Long non-coding RNA PVT1 predicts poor prognosis and induces radioresistance by regulating DNA repair and cell apoptosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Zou, H.; Yang, H.; Wang, L.; Chu, H.; Jiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, A. Long noncoding RNA plasmacytoma variant trans-location 1 gene promotes the development of cervical cancer via the NFkappaB pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 2433–2440. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Huang, J. Clinical significance of the expression of long non-coding RNA PVT1 in glioma. Cancer Biomark. 2019, 24, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Cao, S.; Li, C.; Xu, M.; Wei, H.; Yang, H.; Sun, Q.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, L. LncRNA PVT1 regulates growth, migration, and invasion of bladder cancer by miR-31/ CDK1. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 4799–4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, W.; Zhang, J.; Ge, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Peng, W.; Wang, D.; Gong, A.; Xu, M. Long noncoding RNA PVT1 promotes epithelialmesenchymal transition via the TGFbeta/Smad pathway in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2018, 40, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Peng, X.; Jin, H.; Liu, J. Long non-coding RNA PVT1 promotes autophagy as ceRNA to target ATG3 by sponging microRNA-365 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gene 2019, 697, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Liu, G.; Zhang, X.; Du, N. Long noncoding RNA TMEM75 promotes colorectal cancer progression by activation of SIM2. Gene 2018, 675, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wang, P.; Mo, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Deng, T.; Zhou, M.; Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, C. lncRNA-CCDC26, as a novel biomarker, predicts prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncol Lett. 2019, 18, 2203–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, T.; Yoshikawa, R.; Harada, H.; Harada, Y.; Ishida, A.; Yamazaki, T. Long noncoding RNA, CCDC26, controls myeloid leukemia cell growth through regulation of KIT expression. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, S.; Hui, Y.; Li, X.; Jia, Q. Silencing of lncRNA CCDC26 Restrains the Growth and Migration of Glioma Cells In Vitro and In Vivo via Targeting miR-203. Oncol. Res. Featur. Preclin. Clin. Cancer Ther. 2018, 26, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, K.; Liu, M.; Cao, Y. New Insight into microRNA Functions in Cancer: Oncogene–microRNA–Tumor Suppressor Gene Network. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2017, 4, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, D.; Hu, Y. Long Non-coding RNA PVT1 Competitively Binds MicroRNA-424-5p to Regulate CARM1 in Radiosensi-tivity of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2019, 16, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, L.; Hu, N.; Wang, C.; Zhao, H.; Gu, Y. Long non-coding RNA CCAT1 promotes multiple myeloma progression by acting as a molecular sponge of miR-181a-5p to modulate HOXA1 expression. Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, Y.; Yue, P.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Li, Y. PCAT-1 contributes to cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer through miR-128/ZEB1 axis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 118, 109255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Kong, D.; Sun, D.; Li, J. Long non-coding RNA CCAT2 acts as an oncogene in osteosarcoma through regulation of miR-200b/VEGF. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 2994–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tong, W.; Han, T.C.; Wang, W.; Zhao, J. LncRNA CASC11 promotes the development of lung cancer through targeting mi-croRNA-302/CDK1 axis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 6539–6547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Li, K.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.-L.; He, C.; Wang, H. Down-regulation of long noncoding RNA PVT1 inhibits esophageal carcinoma cell migration and invasion and promotes cell apoptosis via microRNA-145-mediated inhibition of FSCN1. Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 2554–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, J.; Yu, Y.; Li, H.; Hu, Q.; Chen, X.; He, Y.; Xue, C.; Ren, F.; Ren, Z.; Li, J.; et al. Long non-coding RNA PVT1 promotes tumor progression by regulating the miR-143/HK2 axis in gallbladder cancer. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fu, C.; Li, D.; Zhang, X.; Liu, N.; Chi, G.; Jin, X. LncRNA PVT1 Facilitates Tumorigenesis and Progression of Glioma via Regulation of MiR-128-3p/GREM1 Axis and BMP Signaling Pathway. Neurotherapeutics 2018, 15, 1139–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, Z.; Cui, J.; Song, Y. Long noncoding RNA PVT1 promotes EMT via mediating microRNA-186 targeting of Twist1 in prostate cancer. Gene 2018, 654, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Han, X.; Hu, Z.; Chen, L. The PVT1/miR-216b/Beclin-1 regulates cisplatin sensitivity of NSCLC cells via modulating autophagy and apoptosis. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2019, 83, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.-J.; Zhao, L.-F.; Jia, C.-W.; Xu, M.-Y. Long noncoding RNA PVT1 enhances the viability and invasion of papillary thyroid carcinoma cells by functioning as ceRNA of microRNA-30a through mediating expression of insulin like growth factor 1 receptor. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 104, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Chen, W.; Peng, J.; Li, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Shao, C.; Yang, W.; Yao, H.; Zhang, S. LncRNA PVT1 triggers Cy-to-protective autophagy and promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma development via the miR-20a-5p/ULK1 Axis. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Hu, L.; Cheng, J.; Xu, J.; Zhong, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, Z. lncRNA PVT1 promotes the angiogenesis of vascular endothelial cell by targeting miR-26b to activate CTGF/ANGPT2. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chang, Q.-Q.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chen, Z.; Chang, S. LncRNA PVT1 promotes proliferation and invasion through enhancing Smad3 expression by sponging miR-140-5p in cervical cancer. Radiol. Oncol. 2019, 53, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, Y.; Luo, X.; He, W.; Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Lai, Y.; Ye, Y. Long Non-Coding RNA PVT1/miR-150/ HIG2 Axis Regulates the Proliferation, Invasion and the Balance of Iron Metabolism of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 49, 1403–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Liu, S.; Xing, G.; Wang, F. lncRNA PVT1/MicroRNA-17-5p/PTEN Axis Regulates Secretion of E2 and P4, Proliferation, and Apoptosis of Ovarian Granulosa Cells in PCOS. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2020, 20, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Longfei, L.; Long, W.; Feng, Z.; Chen, J.; Chao, L.; Peihua, L.; Xiongbing, Z.; Chen, H. LncRNA PVT1 regulates VEGFC through inhibiting miR-128 in bladder cancer cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 1346–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, C.; Chen, Y.; Kong, W.; Fu, L.; Liu, Y.; Yao, Q.; Yuan, Y. PVT1-derived miR-1207-5p promotes breast cancer cell growth by targeting STAT6. Cancer Sci. 2017, 108, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, H. Long non-coding RNA CCAT1/miR-218/ZFX axis modulates the progression of laryngeal squamous cell cancer. Tumour Biol. 2017, 39, 1010428317699417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dou, C.; Sun, L.; Jin, X.; Han, M.; Zhang, B.; Li, T. Long non-coding RNA colon cancer-associated transcript 1 functions as a competing endogenous RNA to regulate cyclin-dependent kinase 1 expression by sponging miR-490-3p in hepatocellular car-cinoma progression. Tumour Biol. 2017, 39, 1010428317697572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, C.; Li, X.; Fan, Q.; Liu, G.; Yin, J. CCAT1 promotes triple-negative breast cancer progression by suppressing miR-218/ZFX signaling. Aging 2019, 11, 4858–4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Chang, J.; Du, X.; Hou, J. Long non-coding RNA PCAT-1 contributes to tumorigenesis by regulating FSCN1 via miR-145-5p in prostate cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 95, 1112–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Cao, J.; Zhong, Q.; Zeng, L.; Cai, C.; Lei, L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, F. Long noncoding RNA PCAT-1 promotes invasion and metastasis via the miR-129-5p-HMGB1 signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 95, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, G.; Wang, C.-X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Hu, S.; Cao, Z.; Min, B.; Li, L.; Tian, X.; Hu, H.-B. Long noncoding RNA CCAT2 functions as a competitive endogenous RNA to regulate FOXC1 expression by sponging miR-23b-5p in lung adenocarcinoma. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 7998–8007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Jiang, A. Long noncoding RNA CCDC26 as a potential predictor biomarker contributes to tumorigenesis in pan-creatic cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016, 83, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.; Wijesinghe, S.; Halsall, J.; Kanhere, A. A long intergenic non-coding RNA regulates nuclear localisation of DNA methyl transferase-1. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, H.-T.; Fang, L.; Cheng, Y.-X.; Sun, Q. LncRNA PVT1 regulates prostate cancer cell growth by inducing the methylation of miR-146a. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 3512–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, G.; Liu, J. Long noncoding RNA PVT1 promotes cervical cancer progression through epigenetically silencing miR-200b. APMIS 2016, 124, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Fang, F.; Li, P.; Wang, B. LncRNA PCAT1 promotes metastasis of endometrial carcinoma through epigenetical downregulation of E-cadherin associated with methyltransferase EZH2. Life Sci. 2020, 243, 117295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Deng, G.; Liu, T.; Chen, W.; Zhou, Y. Long noncoding RNA PCAT-1 acts as an oncogene in osteosarcoma by reducing p21 levels. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 2622–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.Y.; Ferracin, M.; Pileczki, V.; Chen, B.; Redis, R.; Fabris, L.; Zhang, X.; Ivan, C.; Shimizu, M.; Rodriguez-Aguayo, C.; et al. Cancer-associated rs6983267 SNP and its accompanying long noncoding RNA CCAT2 induce myeloid malignancies via unique SNP-specific RNA mutations. Genome Res. 2018, 28, 432–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shtivelman, E.; Bishop, J.M. The PVT gene frequently amplifies with MYC in tumor cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1989, 9, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, M.; Mo, Y.; Li, X.; Li, G.; Zeng, Z.; Xiong, W.; He, Y. Long non-coding RNA PVT1 interacts with MYC and its downstream molecules to synergistically promote tumorigenesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 4275–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tseng, Y.Y.; Moriarity, B.S.; Gong, W.; Akiyama, R.; Tiwari, A.; Kawakami, H.; Ronning, P.; Reuland, B.; Guenther, K.; Beadnell, T.C.; et al. PVT1 dependence in cancer with MYC copy-number increase. Nature 2014, 512, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnsson, P.; Morris, K.V. Expanding the functional role of long noncoding RNAs. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 1284–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yeh, E.; Cunningham, M.; Arnold, H.; Chasse, D.; Monteith, T.; Ivaldi, G.; Hahn, W.C.; Stukenberg, P.T.; Shenolikar, S.; Uchida, T.; et al. A signalling pathway controlling c-Myc degradation that impacts oncogenic trans-formation of human cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004, 6, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.W.; Xu, J.; Sun, R.; Mumbach, M.R.; Carter, A.C.; Chen, Y.G.; Yost, K.E.; Kim, J.; He, J.; Nevins, S.A.; et al. Promoter of lncRNA Gene PVT1 Is a Tumor-Suppressor DNA Boundary Element. Cell 2018, 173, 1398–1412.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prensner, J.R.; Chen, W.; Han, S.; Iyer, M.K.; Cao, Q.; Kothari, V.; Evans, J.R.; Knudsen, K.E.; Paulsen, M.T.; Ljungman, M.; et al. The long non-coding RNA PCAT-1 promotes prostate cancer cell proliferation through cMyc. Neoplasia 2014, 16, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kajino, T.; Shimamura, T.; Gong, S.; Yanagisawa, K.; Ida, L.; Nakatochi, M.; Griesing, S.; Shimada, Y.; Kano, K.; Suzuki, M.; et al. Divergent lncRNA MYMLR regulates MYC by eliciting DNA looping and promoter-enhancer interaction. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e98441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.-F.; Yin, Q.-F.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.-O.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H.-B.; Ge, J.; Lu, X.; et al. Human colorectal cancer-specific CCAT1-L lncRNA regulates long-range chromatin interactions at the MYC locus. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arakawa, N.; Sugai, T.; Habano, W.; Eizuka, M.; Sugimoto, R.; Akasaka, R.; Toya, Y.; Yamamoto, E.; Koeda, K.; Sasaki, A.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of DNA copy number alterations in early and advanced gastric cancers. Mol. Carcinog. 2016, 56, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, R.; Ching, H.C.; Seong, M.K.; Har, Y.C.; Taib, N.A.M. Integrated analysis of copy number and loss of heterozygosity in primary breast carcinomas using high-density SNP array. Int. J. Oncol. 2011, 39, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alberto, L.; Tolomeo, D.; Cifola, I.; Severgnini, M.; Turchiano, A.; Augello, B.; Squeo, G.; Pietro, D.; Traversa, D.; Daniele, G.; et al. MYC-containing amplicons in acute myeloid leukemia: Genomic structures, evolution, and transcriptional consequences. Leukemia 2018, 32, 2152–2166. [Google Scholar]

- Haverty, P.M.; Hon, L.S.; Kaminker, J.S.; Chant, J.; Zhang, Z. High-resolution analysis of copy number alterations and associated expression changes in ovarian tumors. BMC Med Genom. 2009, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Radtke, I.; Mullighan, C.G.; Ishii, M.; Su, X.; Cheng, J.; Ma, J.; Ganti, R.; Cai, Z.; Goorha, S.; Pounds, S.B.; et al. Genomic analysis reveals few genetic alterations in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 12944–12949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quigley, D.A.; Dang, H.X.; Zhao, S.G.; Lloyd, P.; Aggarwal, R.; Alumkal, J.J.; Foye, A.; Kothari, V.; Perry, M.D.; Bailey, A.M.; et al. Genomic Hallmarks and Structural Variation in Meta-static Prostate Cancer. Cell 2018, 174, 758–769.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vargas-Rondon, N.; Villegas, V.E.; Rondon-Lagos, M. The Role of Chromosomal Instability in Cancer and Therapeutic Re-sponses. Cancers 2017, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cory, S.; Graham, M.; Webb, E.; Corcoran, L.; Adams, J.M. Variant (6;15) translocations in murine plasmacytomas involve a chromosome 15 locus at least 72 kb from the c-myc oncogene. EMBO J. 1985, 4, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.; Adams, J.M. Chromosome 8 breakpoint far 3’ of the c-myc oncogene in a Burkitt’s lymphoma 2;8 variant translocation is equivalent to the murine pvt-1 locus. EMBO J. 1986, 5, 2845–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinen, Y.; Sakamoto-Inada, N.; Nagoshi, H.; Taki, T.; Maegawa, S.; Tatekawa, S.; Tsukamoto, T.; Mizutani, S.; Shimura, Y.; Yamamoto-Sugitani, M.; et al. 8q24 amplified segments involve novel fusion genes between NSMCE2 and long noncoding RNAs in acute myelogenous leukemia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2014, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nagoshi, H.; Taki, T.; Hanamura, I.; Nitta, M.; Otsuki, T.; Nishida, K.; Okuda, K.; Sakamoto, N.; Kobayashi, S.; Yamamoto-Sugitani, M.; et al. Frequent PVT1 rearrangement and novel chi-meric genes PVT1-NBEA and PVT1-WWOX occur in multiple myeloma with 8q24 abnormality. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 4954–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taniwaki, M. Recent advancements in molecular cytogenetics for hematological malignancies: Identification of novel PVT1 fusion genes. Rinsho Ketsueki 2015, 56, 2056–2065. [Google Scholar]

- Northcott, P.A.; Shih, D.J.H.; Peacock, J.; Garzia, L.; Morrissy, A.S.; Zichner, T.; Stuetz, A.M.; Korshunov, A.; Reimand, J.; Schumacher, S.E.; et al. Subgroup-specific structural variation across 1000 medulloblastoma genomes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 488, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sarver, A.L.; Murray, C.D.; Temiz, N.A.; Tseng, Y.Y.; Bagchi, A. MYC and PVT1 synergize to regulate RSPO1 levels in breast cancer. Cell Cycle 2016, 15, 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, K.; Ding, L.; Chang, T.-C.; Shao, Y.; Chiang, J.; Mulder, H.; Wang, S.; Shaw, T.I.; Wen, J.; Hover, L.; et al. Structure and evolution of double minutes in diagnosis and relapse brain tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 137, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Storlazzi, C.T.; Fioretos, T.; Surace, C.; Lonoce, A.; Mastrorilli, A.; Strömbeck, B.; D’Addabbo, P.; Iacovelli, F.; Minervini, C.; Aventin, A.; et al. MYC-containing double minutes in hematologic malignancies: Evidence in favor of the episome model and exclusion of MYC as the target gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, T.; Ike, F.; Murata, T.; Obata, Y.; Utiyama, H.; Yokoyama, K.K. Genes encoded within 8q24 on the amplicon of a large extrachromosomal element are selectively repressed during the terminal differentiation of HL-60 cells. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2008, 640, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Redis, R.S.; Vela, L.E.; Lu, W.; de Oliveira, J.F.; Ivan, C.; Rodriguez-Aguayo, C.; Adamoski, D.; Pasculli, B.; Taguchi, A.; Chen, Y.; et al. Allele-Specific Reprogramming of Cancer Metabolism by the Long Non-coding RNA CCAT2. Mol. Cell. 2016, 61, 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jendrzejewski, J.; He, H.; Radomska, H.S.; Li, W.; Tomsic, J.; Liyanarachchi, S.; Davuluri, R.V.; Nagy, R.; De La Chapelle, A. The polymorphism rs944289 predisposes to papillary thyroid carcinoma through a large intergenic noncoding RNA gene of tumor suppressor type. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8646–8651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hua, J.T.; Ahmed, M.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Soares, F.; Lu, J.; Zhou, S.; Wang, M.; Li, H.; et al. Risk SNP-Mediated Promoter-Enhancer Switching Drives Prostate Cancer through lncRNA PCAT19. Cell 2018, 174, 564–575.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuan, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, Z.; Owzar, K.; Han, Y.; Su, L.; Wei, Y.; Hung, R.J.; McLaughlin, J.; Brhane, Y.; et al. A Novel Genetic Variant in Long Non-coding RNA Gene NEXN-AS1 is Associated with Risk of Lung Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, M.; Habibi, M.; Noroozi, R.; Rakhshan, A.; Sarrafzadeh, S.; Sayad, A.; Omrani, M.D.; Ghafouri-Fard, S. HOTAIR genetic variants are associated with prostate cancer and benign prostate hyperplasia in an Iranian population. Gene 2017, 613, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.-R.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, A.-Y. lncRNASNP2: An updated database of functional SNPs and mutations in human and mouse lncRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D276–D280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Meng, Q.; Yang, H.; Zhu, H.; Tang, W.; Li, X.; Aschner, M.; et al. MALAT1 rs664589 Poly-morphism Inhibits Binding to miR-194-5p, Contributing to Colorectal Cancer Risk, Growth, and Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 5432–5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shen, C.; Yan, T.; Wang, Z.; Su, H.-C.; Zhu, X.; Tian, X.; Fang, J.-Y.; Chen, H.; Hong, J. Variant of SNP rs1317082 at CCSlnc362 (RP11-362K14.5) creates a binding site for miR-4658 and diminishes the susceptibility to CRC. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Onay, U.V.; Briollais, L.; Knight, J.A.; Shi, E.; Wang, Y.; Wells, S.; Li, H.; Rajendram, I.; Andrulis, I.L.; Ozcelik, H. SNP-SNP interactions in breast cancer susceptibility. BMC Cancer 2006, 6, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, H.-Y.; Callan, C.Y.; Fang, Z.; Tung, H.-Y.; Park, J.Y. Interactions of PVT1 and CASC11 on Prostate Cancer Risk in African Americans. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019, 28, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tseng, Y.Y.; Bagchi, A. The PVT1-MYC duet in cancer. Mol. Cell. Oncol. 2015, 2, e974467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Homer-Bouthiette, C.; Zhao, Y.; Shunkwiler, L.; Van Peel, B.; Garrett-Mayer, E.; Baird, R.C.; Rissman, A.I.; Guest, S.T.; Ethier, S.P.; John, M.C.; et al. Deletion of the murine ortholog of the 8q24 gene desert has anti-cancer effects in transgenic mammary cancer models. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ma, L. New Insights into Long Non-Coding RNA MALAT1 in Cancer and Metastasis. Cancers 2019, 11, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| 8q24.21 LncRNA | Cancers in Which the lncRNA Has Been Studied |

|---|---|

| PCAT1 | Colorectal cancer [40], hepatocellular carcinoma [41], extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma [42], oesophageal squamous carcinoma [43], breast cancer [44], head and neck squamous carcinoma [45], laryngeal cancer [46], osteosarcoma [47], bladder cancer [48], glioma [49] |

| CASC19 | Colorectal cancer [50], cervical cancer [51] |

| PRNCR1 | Non-small cell lung cancer [52], tongue squamous cell carcinoma [53] |

| CCAT1 | Colon cancer [54], endometrial cancer [55], prostate cancer [56], ovarian cancer [57], gastric cancer [58], hepatocellular carcinoma [59], breast cancer [60], cervical cancer [61], melanoma [62], laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma [63], glioma [64], oral squamous cell carcinoma [65], retinoblastoma [66], gallbladder cancer [67], oesophageal cancer [68], acute myeloid leukaemia [69], non-small cell lung cancer [70], osteosarcoma [71], nasopharynx cancer [72] |

| CASC8 | Colorectal cancer [73], bladder cancer [74], lung cancer [75], hepatocellular carcinoma [76] |

| CCAT2 | Colon cancer [77], pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [78], osteosarcoma [79], oesophageal carcinoma [80], hepatocellular carcinoma [76], acute myeloid leukaemia [81], non-small cell lung cancer [82], lung adenocarcinoma [83], ovarian carcinoma [84], endometrial cancer [85], breast cancer [86], renal cell carcinoma [87], epithelial ovarian cancer [88], glioma [89], prostate cancer [90] |

| CASC11 | Colorectal cancer [91], cervical cancer [92], gastric cancer [93], bladder cancer [94], small cell lung cancer [95], non-small cell lung cancer [96], hepatocellular carcinoma [97], oesophageal carcinoma [98], neonatal neuroblastoma [99], ovarian squamous cell carcinoma [100], osteosarcoma [101], glioma [102] |

| PVT1 | Non-small cell lung cancer [103], colon cancer [104], ovarian cancer [105], oesophageal adenocarcinoma [106], nasopharyngeal carcinoma [107], cervical cancer [108], glioma [109], bladder cancer [110], pancreatic cancer [111], hepatocellular carcinoma [112] |

| TMEM75 | Colorectal cancer [113] |

| CCDC26 | Acute myeloid leukaemia [114], acute monocytic leukaemia [115], chronic myeloid leukaemia [115], glioma [116] |

| 8q24.21 LncRNA | miRNAs and Affected Target Genes |

|---|---|

| PVT1 | miR-424-5p (CARM1) [119], miR-145 (FSCN1) [124], miR-143 (HK2) [125], miR-128-3p (GREM1) [126], miR-186 (Twist1) [127], miR-216b (Beclin-1) [128], miR-30a (IGF1) [129], miR-20a-5p (ULK1) [130], miR-29c (VEGF) [103], miR-26b (CTGF) [131], miR-140-5p (SMAD3) [132], miR-150 (HIG2) [133], miR-365 (ATG3) [112], miR-17-5p (PTEN) [134], miR-31 (CDK1) [110], miR-128 (VEGF) [135], miR-1207-5p (STAT6) [136] |

| CCAT1 | miR-181a-5p (HOXA1) [120], miR-143 (PLK1) [68], miR-148a (PKC) [56], miR-130a-3p (SOX4) [70], miR-218 (ZFX) [137], miR-148 (PIK3IP1) [71], miR-490-3p (CDK1) [138], miR-181a (CPEB2) [72], miR-218 (ZFX) [139] |

| PCAT1 | miR-128 (ZEB1) [121], miR-145-5p (FSCN1) [140], miR-129-5p (HMGB1) [141], miR-122 (WNT1) [42] |

| CCAT2 | miR-200b (VEGF) [122], miR-23b-5p (FOXC1) [142], miR-424 (VEGFA) [89] |

| CASC11 | miR-302 (CDK1) [123], miR-676-3p (NOL4L) [99], miR-498 (FOXK1) [102] |

| PRNCR1 | miR-944 (HOXB5) [53], miR-126-5p (MTDH) [52] |

| CASC19 | miR-140-5p (CEMIP) [50] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wilson, C.; Kanhere, A. 8q24.21 Locus: A Paradigm to Link Non-Coding RNAs, Genome Polymorphisms and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22031094

Wilson C, Kanhere A. 8q24.21 Locus: A Paradigm to Link Non-Coding RNAs, Genome Polymorphisms and Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(3):1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22031094

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilson, Claire, and Aditi Kanhere. 2021. "8q24.21 Locus: A Paradigm to Link Non-Coding RNAs, Genome Polymorphisms and Cancer" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 3: 1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22031094