An Android Malicious Code Detection Method Based on Improved DCA Algorithm

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Works

3. Problem Statement and Preliminaries

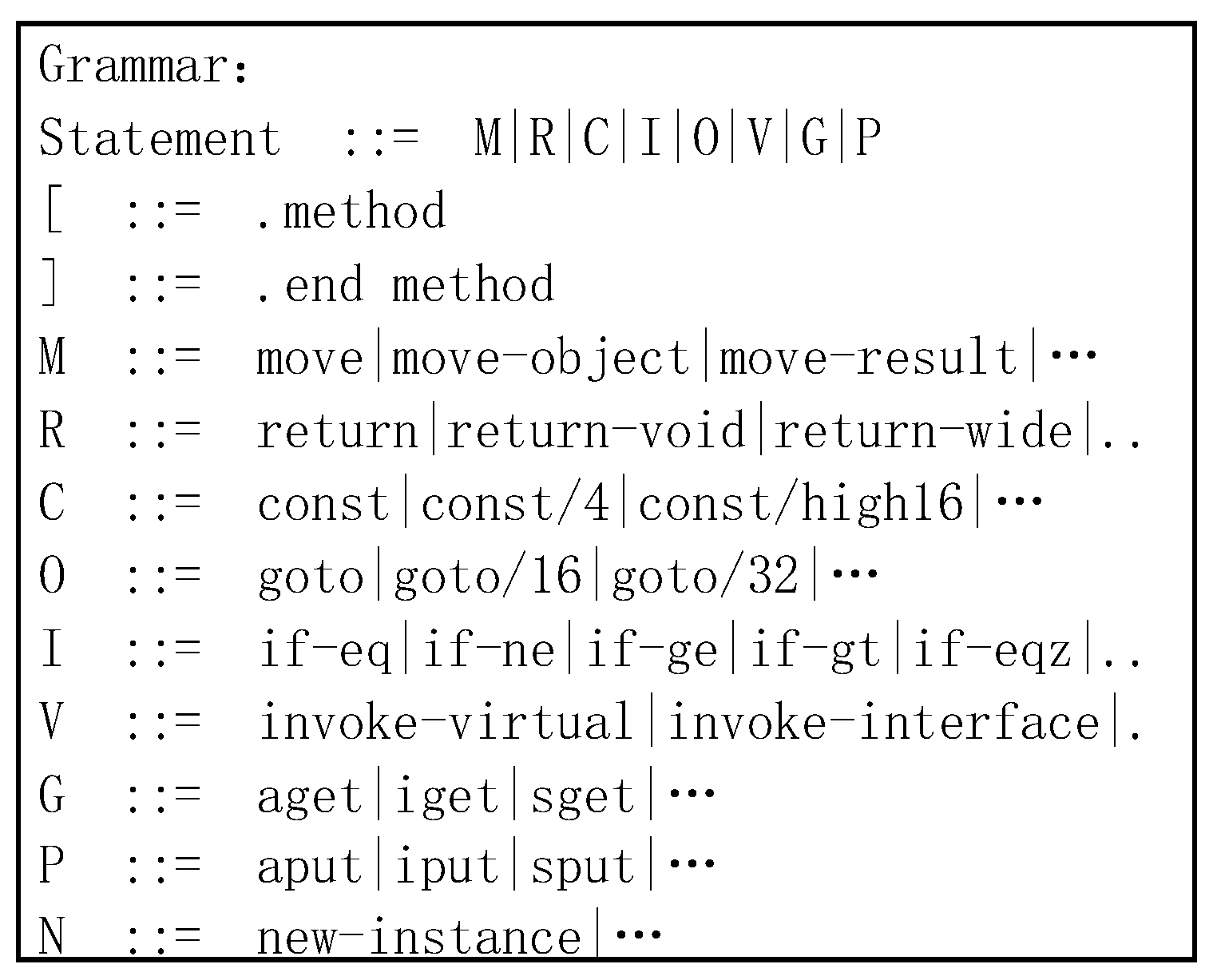

3.1. Dalvik Reduced Instruction Set

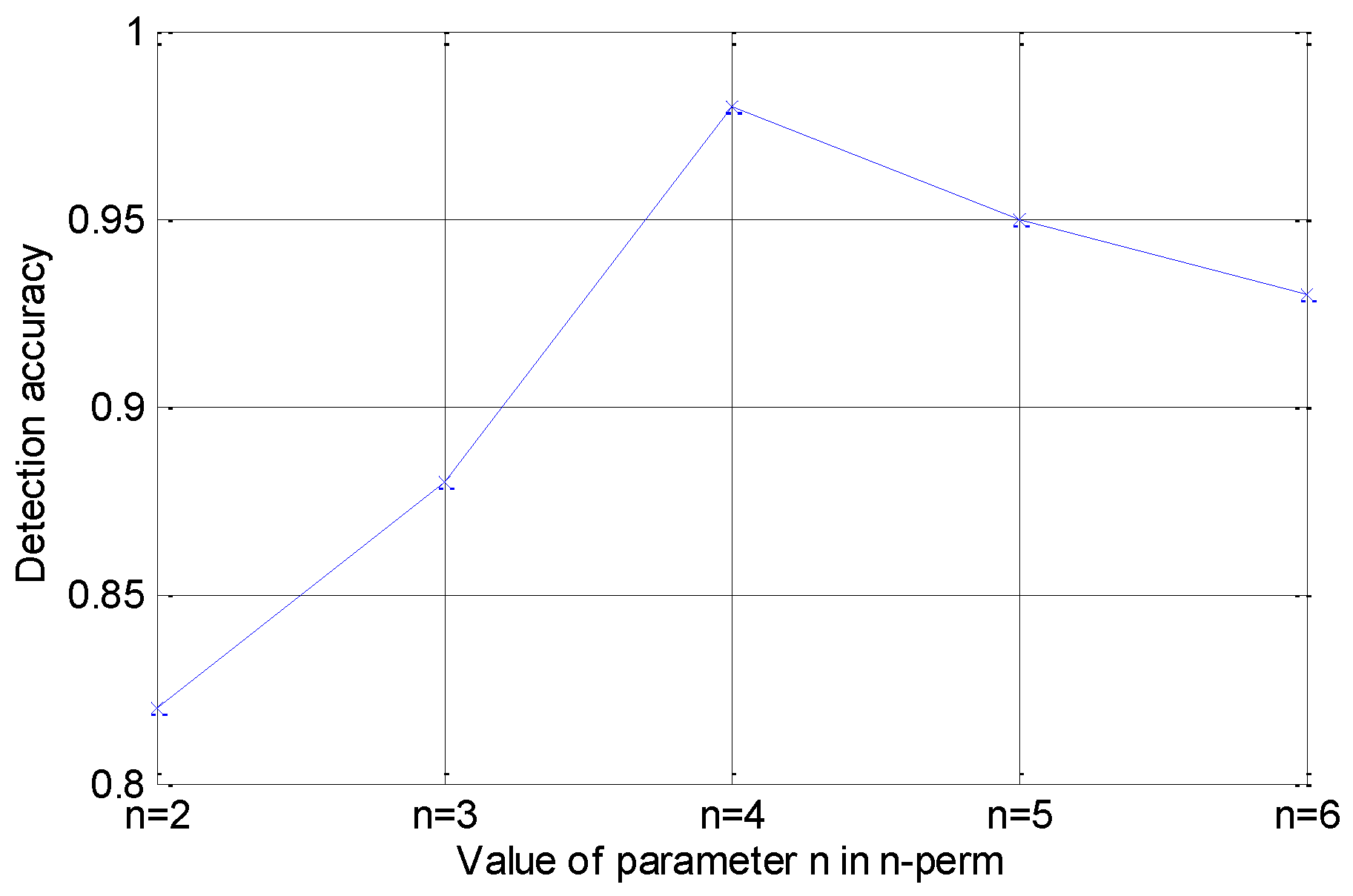

3.2. N-Perm Algorithm

3.3. DCA Algorithm

3.4. Code Obfuscation

4. Design of Detection Method Based on Improved DCA Algorithm

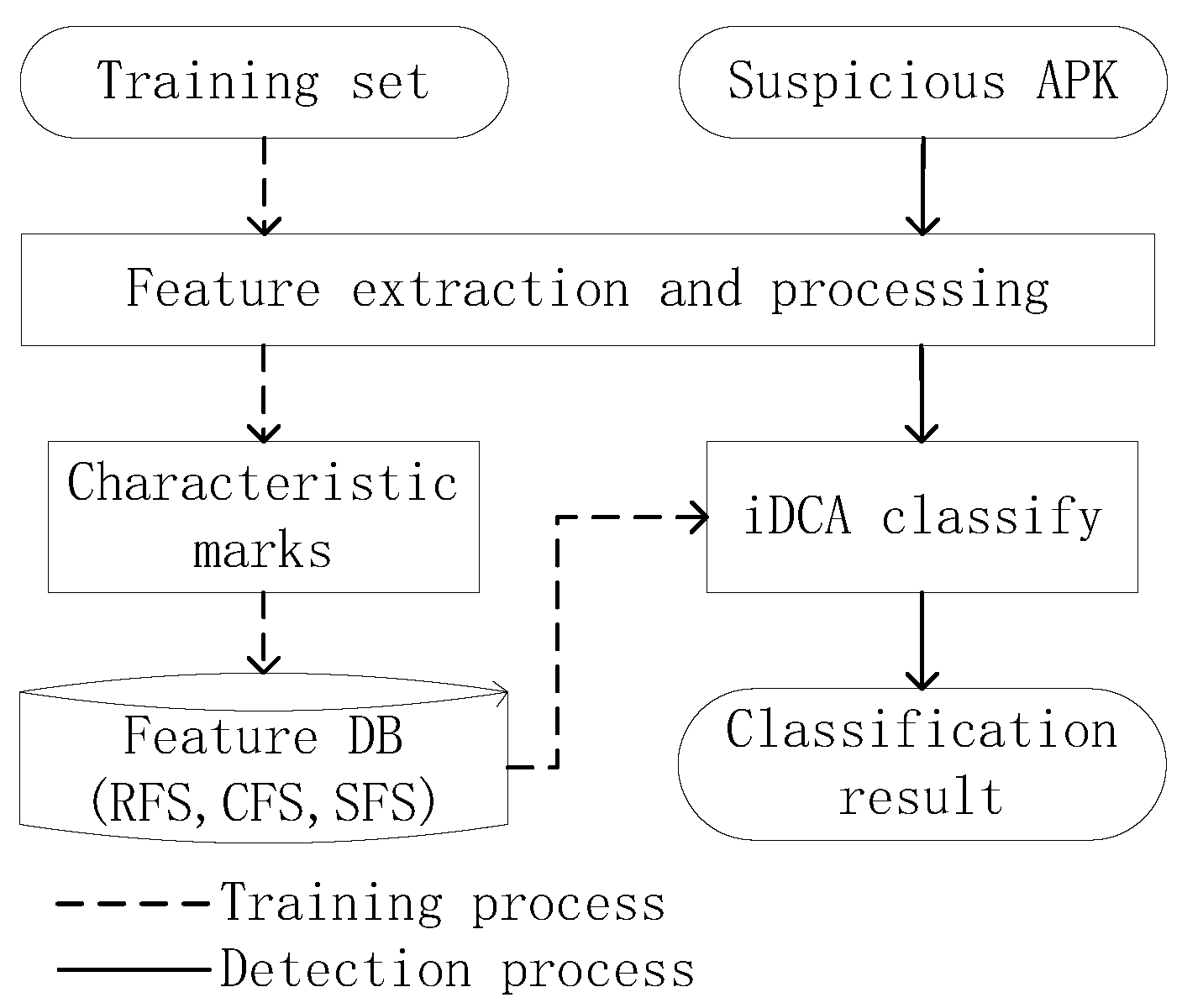

4.1. System Overview

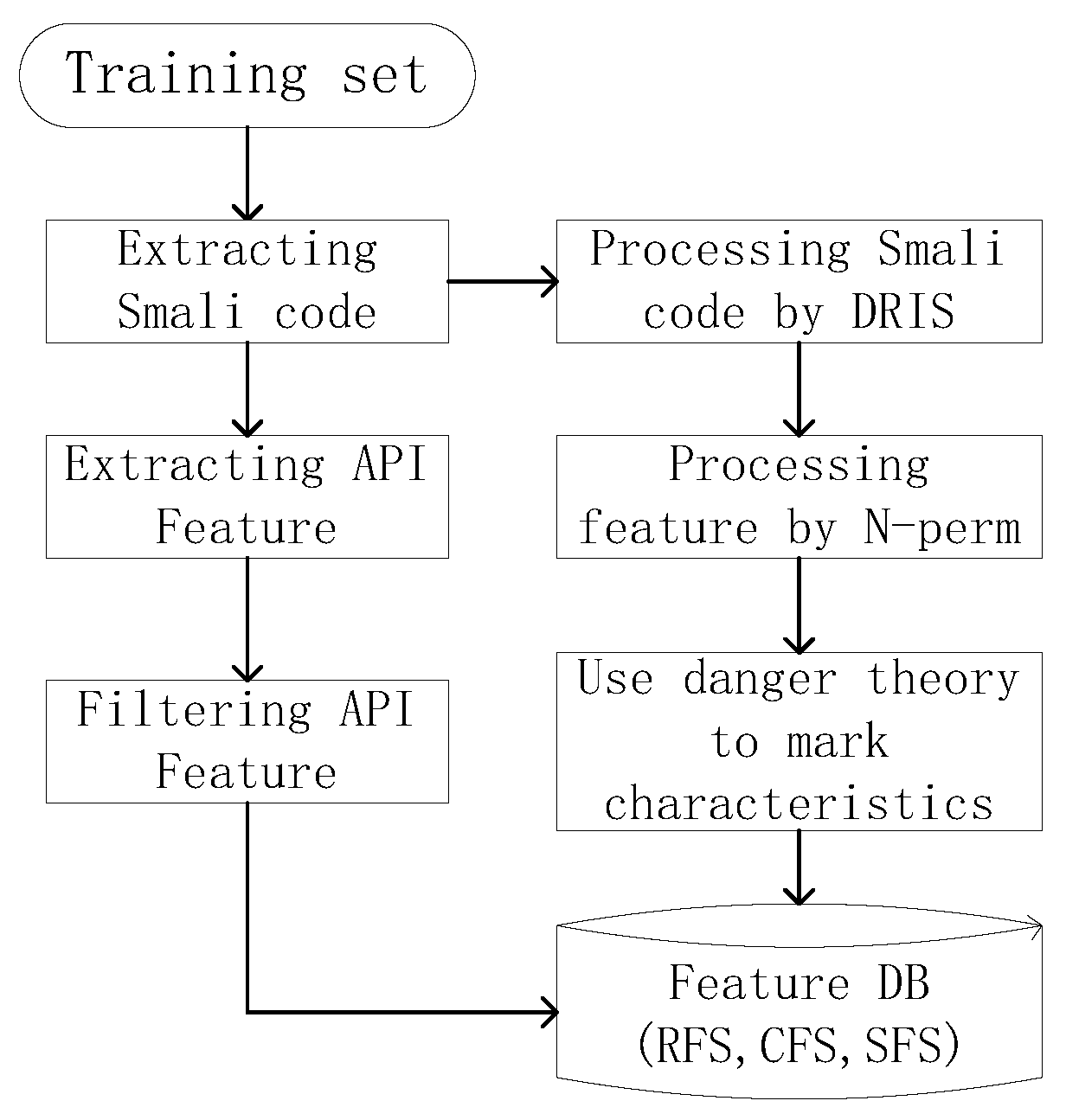

4.2. Training Part

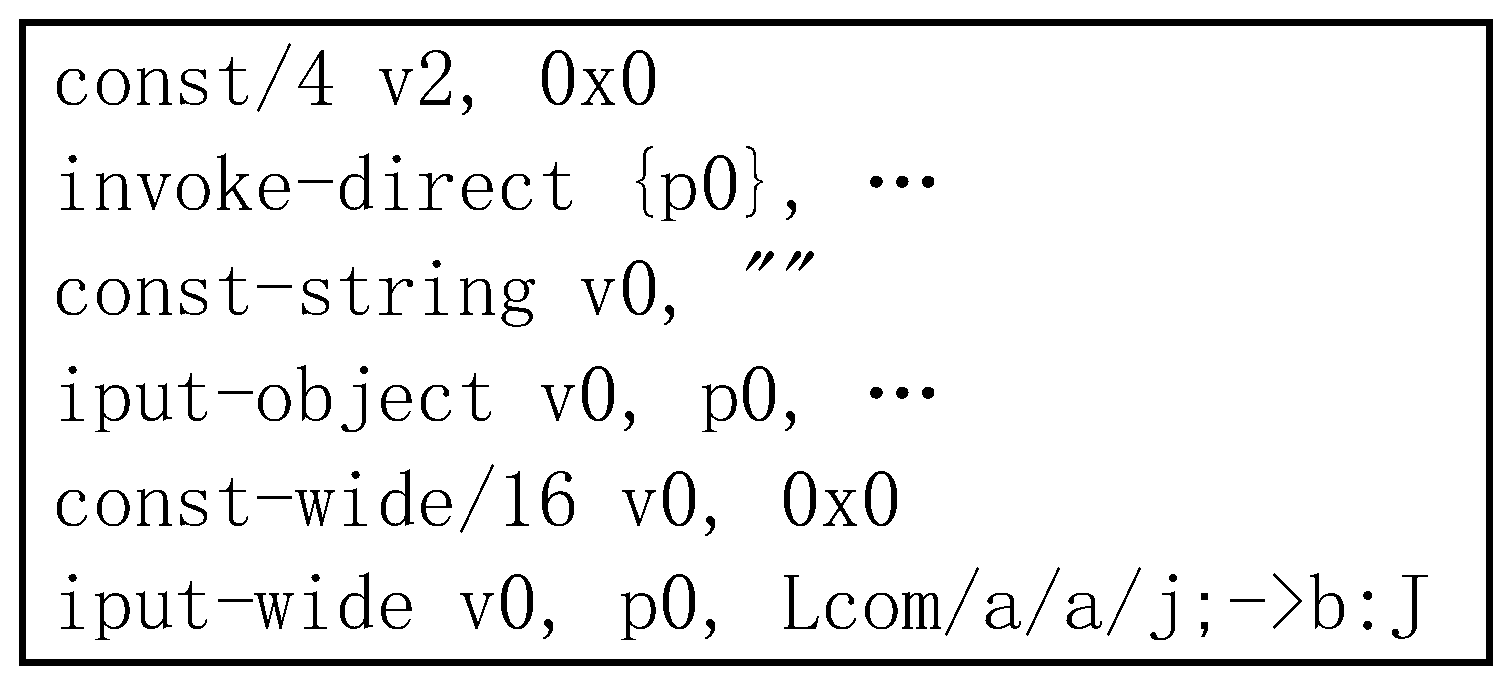

4.2.1. Input Data Processing Method

4.2.2. Mark Characteristic

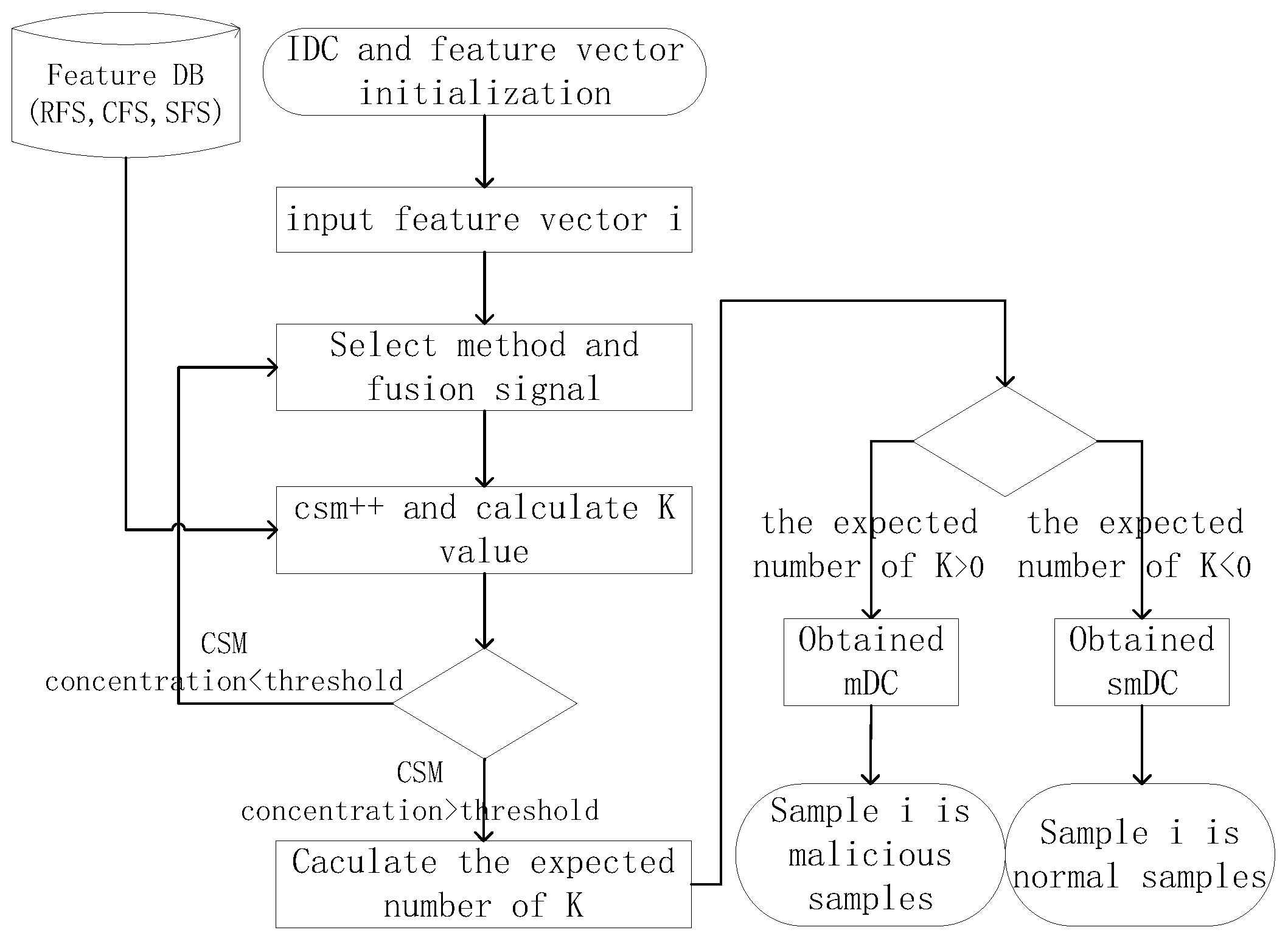

4.3. The Improved Dendritic Cell Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 Pseudocode for iDCA | |

| Input: Antigen and Signals | |

| Output: Antigen Types and | |

| 1: | procedure iDCA |

| 2: | |

| 3: | while do |

| 4: | while do |

| 5: | |

| 6: | |

| 7: | |

| 8: | |

| 9: | |

| 10: | if then |

| 11: | |

| 12: | if then |

| 13: | |

| 14: | else |

| 15: | |

| 16: | end if |

| 17: | end if |

| 18: | end while |

| 19: | |

| 20: | |

| 21: | end while |

| 22: | return |

| 23: | end procedure |

4.4. Analysis of iDCA

5. Experimental Design

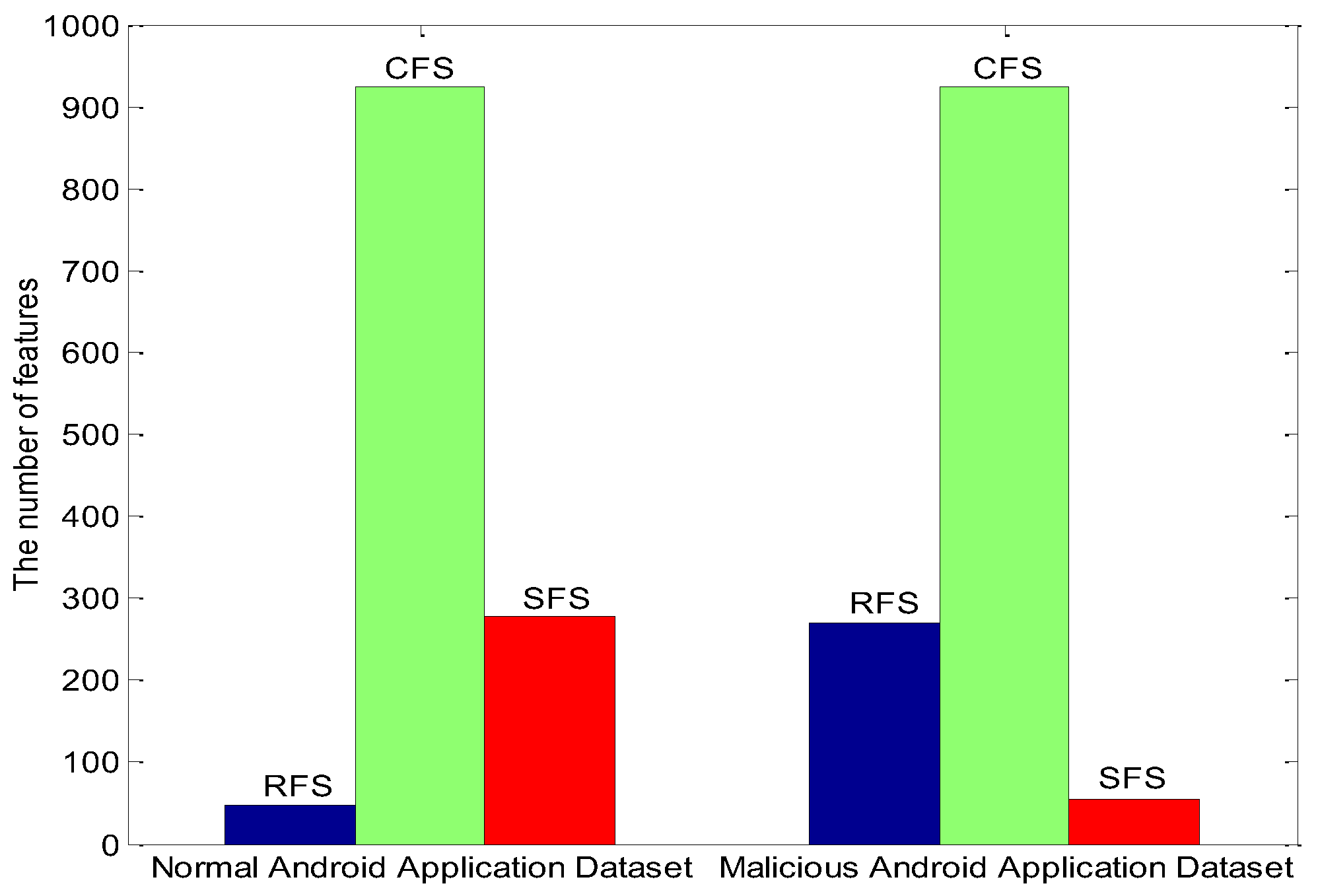

5.1. Experimental Data Processing

5.2. Results Contrast

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/266136/global-market-share-held-by-smartphone-operating-systems/ (accessed on 1 November 2016).

- AVL. Available online: http://blog.avlyun.com/2016/02/2759/2015report/ (accessed on 5 February 2016).

- Shangguan, L.; Yang, Z.; Liu, A.X.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y. Relative localization of RFID tags using spatial-temporal phase profiling. In Proceedings of the 12th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 15th), Oakland, CA, USA, 4–6 May 2015.

- Seo, S.H.; Gupta, A.; Sallam, A.M.; Bertino, E.; Yim, K. Detecting mobile malware threats to homeland security through static analysis. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2014, 38, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabtai, A.; Fledel, Y.; Kanonov, U.; Elovici, Y.; Dolev, S. Google android: A state-of-the-art review of security mechanisms. arXiv, 2009; arXiv:0912.5101. [Google Scholar]

- Si-han, Q. Research Progress on Android Security. J. Softw. 2016, 27, 45–71. [Google Scholar]

- Enck, W.; Ongtang, M.; McDaniel, P. On lightweight mobile phone application certification. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Chicago, IL, USA, 9–13 November 2009; pp. 235–245.

- Ongtang, M.; McLaughlin, S.; Enck, W.; McDaniel, P. Semantically rich application-centric security in Android. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2012, 5, 658–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauman, M.; Khan, S.; Zhang, X. Apex: Extending android permission model and enforcement with user-defined runtime constraints. In Proceedings of the 5th ACM Symposium on Information, Computer and Communications Security, Beijing, China, 13–16 April 2010; pp. 328–332.

- Wognsen, E.R.; Karlsen, H.S.; Olesen, M.C.; Hansen, R.R. Formalisation and analysis of Dalvik bytecode. Sci. Comput. Programm. 2014, 92, 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, B.P.; Li, N.; Gates, C.; Potharaju, R.; Nita-Rotaru, C.; Molloy, I. Android permissions: A perspective combining risks and benefits. In Proceedings of the ACM Symposium on Access Control Models & Technologies Ser Sacmat, Newark, NJ, USA, 20–22 June 2012; pp. 13–22.

- Sato, R.; Chiba, D.; Goto, S. Detecting Android malware by analyzing manifest files. APAN 2013, 36, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.J.; Mao, C.H.; Wei, T.E.; Lee, H.M.; Wu, K.P. Droidmat: Android malware detection through manifest and api calls tracing. In Proceedings of the 2012 Seventh Asia Joint Conference on Information Security (Asia JCIS), Tokyo, Japan, 9–10 August 2012; pp. 62–69.

- Weichselbaum, L.; Neugschwandtner, M.; Lindorfer, M.; Fratantonio, Y.; van der Veen, V.; Platzer, C. Andrubis: Android Malware under the Magnifying Glass; TR-ISECLAB-0414-001; Vienna University of Technology: Vienna, Austria, May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zou, S.; Jiang, X. Riskranker: Scalable and accurate zero-day android malware detection. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services, Lake District, UK, 25–29 June 2012; pp. 281–294.

- Li, T.; Dong, H.; Yuan, C.Y.; Du, Y.J.; Xu, G.A. Description of Android Malware Feature Based on Dalvik Instructions. J. Comput. Res. Dev. 2014, 7, 1458–1466. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Tangil, G.; Tapiador, J.E.; Peris-Lopez, P.; Blasco, J. Dendroid: A text mining approach to analyzing and classifying code structures in Android malware families. Expert Syst. Appl. 2014, 41, 1104–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kong, D.G.; Tan, X.B.; Xi, H.S.; Gong, T.; Shuai, J.M. Obfuscated Malware Detection Based on Boosting Multilevel Features. J. Softw. 2011, 3, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pektas, A.; Eris, M.; Acarman, T. Proposal of n-gram based algorithm for malware classification. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Emerging Security Information, Systems and Technologies, French Riviera, France, 21–27 August 2011; pp. 14–18.

- Ng, D.V.; Hwang, J.I.G. Android malware detection using the dendritic cell algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics (ICMLC), Lanzhou, China, 13–16 July 2014; Volume 1, pp. 257–262.

- Cesare, S.; Xiang, Y. Classification of malware using structured control flow. In Proceedings of the Eighth Australasian Symposium on Parallel and Distributed Computing-Volume 107, Brisbane, Australia, 1 January 2010; pp. 61–70.

- Li, W.J.; Wang, K.; Stolfo, S.J.; Herzog, B. Fileprints: Identifying file types by n-gram analysis. In Proceedings of the Sixth Annual Workshop on Information Assurance, New York, NY, USA, 15–17 June 2005; pp. 64–71.

- Matzinger, P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1994, 12, 991–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greensmith, J. The Dendritic Cell Algorithm. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, C.; Tornquist, P.; Mckenna, R.; Pearson, Z.; Clause, J. How Does Code Obfuscation Impact Energy Usage? In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance and Evolution, Raleigh, NC, USA, 2–10 October 2016; pp. 131–140.

- Faruki, P.; Bharmal, A.; Laxmi, V.; Ganmoor, V.; Gaur, M.S.; Conti, M.; Rajarajan, M. Android Security: A Survey of Issues, Malware Penetration and Defenses. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2014, 17, 998–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, Y.; Jung, J.H.; Yi, J.H. Server-based code obfuscation scheme for APK tamper detection. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2014, 9, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, S.; Shafiq, M.Z.; Tabish, S.M.; Farooq, M. A sense of danger for windows processes. In Artificial Immune Systems; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 220–233. [Google Scholar]

- Rychtáriková, R.; Korbel, J.; Macháček, P.; Císař, P.; Urban, J.; Štys, D. Point Information Gain and Multidimensional Data Analysis. Entropy 2016, 18, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y. Intelligent Security IT System for Detecting Intruders Based on Received Signal Strength Indicators. Entropy 2016, 18, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; Greensmith, J.; Aickelin, U. Theoretical formulation and analysis of the deterministic dendritic cell algorithm. Biosystems 2013, 111, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Johnson, J.T.; Majurec, N.; Frankford, M.; Stewart, K.; Smith, G.E.; Westbrook, L. Simulation and analysis of polarimetric radar signatures of human gaits. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2014, 50, 2164–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.Y.; Park, J.; Fuchs, Z.; Parada, F.; Hanna, P.; Derov, J.; Noyola, M. Multispectral target recognition using adaptive radar and infrared data integration. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 13–18 July 2014; pp. 189–190.

- Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Feng, D.W.; Liu, J.Q.; Han, Z.; Zhang, X.L. Exploring permission-induced risk in Android applications for malicious application detection. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensic Secur. 2014, 9, 1869–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| DC | Dendritic cell, in this paper is APK sample |

| iDC | immature DC, in this paper is test sample |

| smDC | semi-mature DC, in this paper is normal sample |

| mDC | mature DC, in this paper is malicious sample |

| CSM | the concentration of co-stimulatory molecules, represents the process of iDC transforming |

| k | represents the danger degree of single method in current APK |

| a measure indicating the polarisation towards anomaly or normality | |

| M | a set of malicious APK |

| N | a set of normal APK |

| V | a set of suspicious APK |

| S | a set of characteristics after data extraction |

| DS | danger signal, represents the hazard degree |

| SS | safe signal, represents the safe degree |

| RFS | risk feature set, a set contains danger characteristic |

| CFS | common feature set, a set contains common characteristic |

| SFS | safe feature set, a set contains safe characteristic |

| represents the danger degree of current characteristic or method | |

| represents the safe degree of current characteristic or method |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Gong, L.; Mo, X.; Yang, H.; Zhao, Y. An Android Malicious Code Detection Method Based on Improved DCA Algorithm. Entropy 2017, 19, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/e19020065

Wang C, Li Z, Gong L, Mo X, Yang H, Zhao Y. An Android Malicious Code Detection Method Based on Improved DCA Algorithm. Entropy. 2017; 19(2):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/e19020065

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Chundong, Zhiyuan Li, Liangyi Gong, Xiuliang Mo, Hong Yang, and Yi Zhao. 2017. "An Android Malicious Code Detection Method Based on Improved DCA Algorithm" Entropy 19, no. 2: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/e19020065