Camphor—A Fumigant during the Black Death and a Coveted Fragrant Wood in Ancient Egypt and Babylon—A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

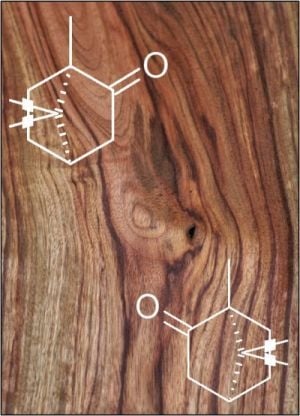

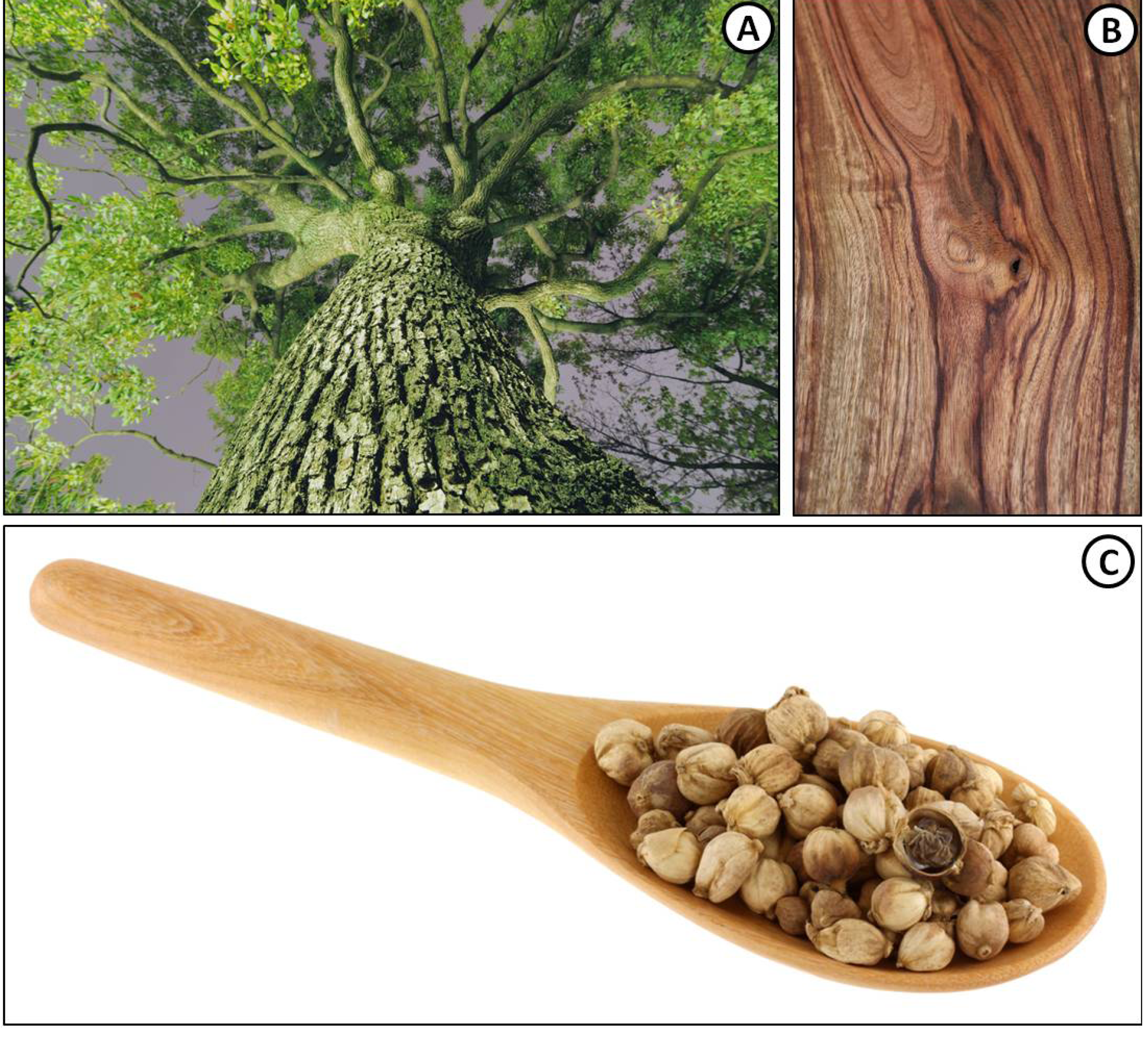

2. Physical Properties and Sources of Camphor

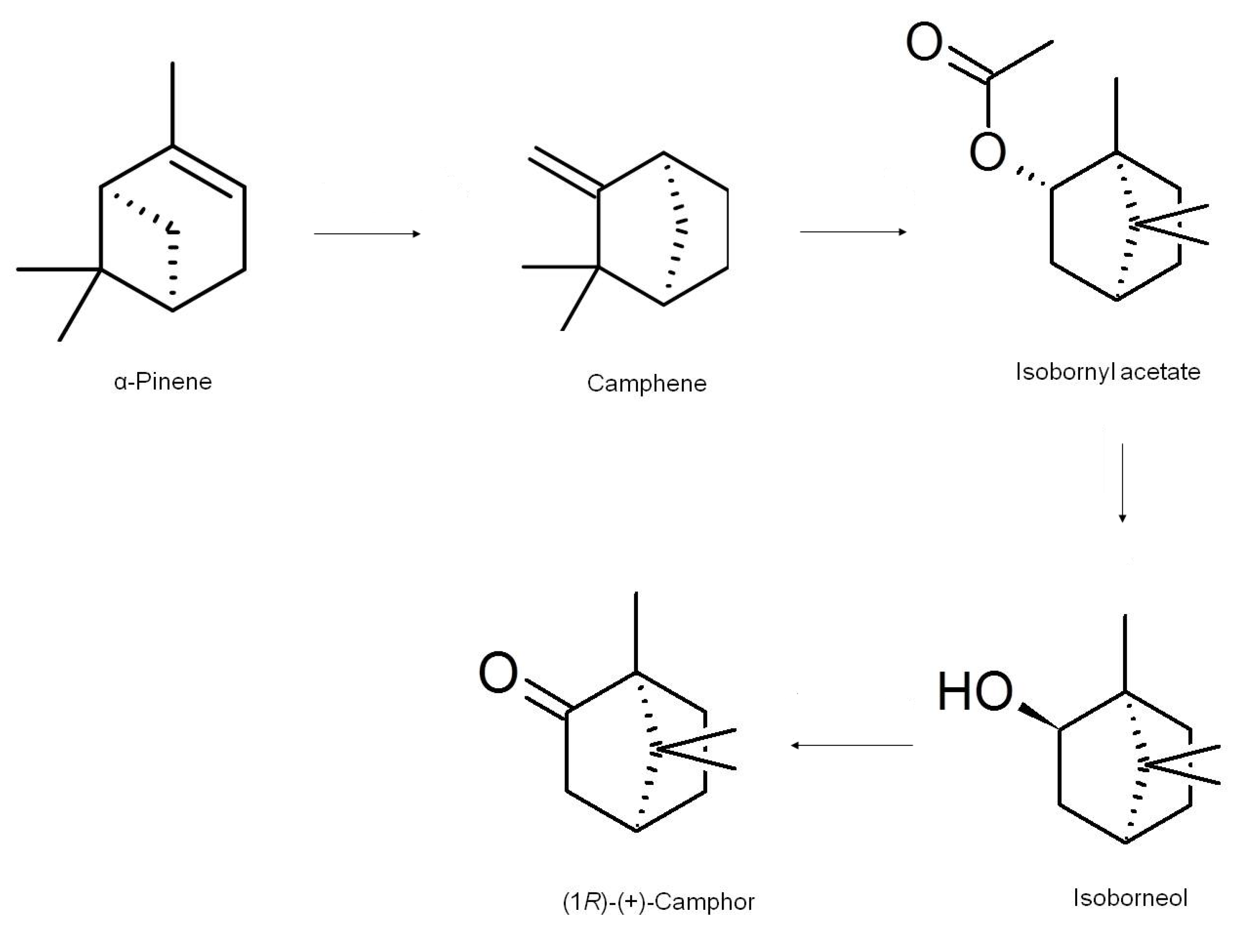

3. Biosynthesis and Chemical Synthesis of Camphor

4. Camphor as a Chiral Starting Material and Auxiliary

5. The Biological Properties of Camphor

5.1. Antimicrobial Activity

5.1.1. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities

5.2. Antitussive Activity

5.3. Anti-Nociceptive Activity

5.4. Antimutagenic and Anticancer Activity

5.5. Insecticidal Activity

5.6. Cardiovascular Effects

5.7. Camphor as a Potential Skin Penetration Enhancer

5.8. Other Applications

5.9. Allelopathic Activity

6. Toxicity of Camphor

7. Conclusions

References

- Keller, H. The World I Live in; Cosimo Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2009; p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- Vernet-Maury, E.; Alaoui-Ismaïli, O.; Dittmar, A.; Delhomme, G.; Chanel, J. Basic emotions induced by odorants: A new approach based on autonomic pattern results. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1999, 75, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, B.E.; van Oudtshoorn, B.; Gericke, N. Medicinal plants of South Africa, 2nd ed.; Briza Publications: Pretoria, South Africa, 2009; p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA); Natural Resources Conservation Service. Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J. Presl (camphor tree). Available online: http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=CICA&photoID=cica_002_ahp.tif/ (accessed on 21 April 2013).

- Hattori, A. Camphor in the Edo era fireworks. Yakushiqaku Zasshi 2001, 36, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Donkin, R.A. Dragon’s brain Perfume: An Historical Geography of Camphor; Koninklijke Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1999; p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Ando, Y. Single-wall and multi-wall carbon nanotubes from camphor-a botanical hydrocarbon. Diamond Relat. Mater. 2003, 12, 1845–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Carneiro, M.R.; Felzenszwalb, I.; Paumgartten, F.J. Mutagenicity testing (+/−)-camphor, 1,8-cineole, citral, citronellal, (−)-menthol and terpineol with the Salmonella/microsome assay. Mutat. Res. 1998, 416, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. Terpenes: The expansion of chiral pool. In Handbook of Chiral Chemicals, 2nd ed.; Ager, D.J., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Juteau, F.; Masotti, V.; Bessière, J.M.; Dherbomez, M.; Viano, J. Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of Artemisia annua essential oil. Fitoterapia 2002, 73, 532–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirillini, B.; Velasquez, E.R.; Pellegrino, R. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oil of Piper angustifolium. Planta Med. 1996, 62, 372–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdem, D.P.; Gage, D.A. Chemical composition of essential oil from the root bark of Sassafras albidum. Planta Med. 1995, 61, 574–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljoen, A.; van Vuuren, S.; Ernst, E.; Klepser, M.; Demirci, B.; Baser, H.; van Wyk, B. Osmitopsis astericoides (Asteraceae)—The antimicrobial activity and essential oil composition of a Cape-Dutch remedy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 88, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerschmidt, F.J.; Clark, A.M.; Soliman, F.M.; El-Kashoury, E.S.; Abd El-Kawy, M.M.; El-Fishawy, A.M. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oils of Jasonia candicans and J. montana. Planta Med. 1993, 59, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpott, N.W. Intramuscular Injections of camphor in the treatment of engorgement of the breasts. CMAC 1929, 20, 494–495. [Google Scholar]

- Liebelt, E.L.; Shannon, M.W. Small doses, big problems: A selected review of highly toxic common medications. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 1993, 19, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.C.; Hobbs, J.B.; Banthorpe, D.V.; Harborne, J.B. Natural Products: Their Chemistry and Biological Significance; Longman Scientific & Technical: Harlow, Essex, UK, 1994; pp. 309–311. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, K.; Garbe, D.; Surburg, H. Common Fragrance and Flavor Materials; Wiley-VCH Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 1997; pp. 49, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Nandi, N. Study of chiral recognition of model peptides and odorants: Carvone and camphor. Curr. Sci. 2005, 88, 1929–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Rebound Health. Camphor. Available online: reboundhealth.com/cms/images/pdf/Textbooks/camphor%20id%2015853.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2013).

- Lopes-Lutz, D.; Alviano, D.S.; Alviano, C.S.; Kolodziejczyk, P.P. Screening of chemical composition, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Artemisia essential oils. Phytochemistry 2008, 8, 1732–1738. [Google Scholar]

- Viljoen, A.M.; Njenga, E.W.; van Vuuren, S.F.; Bicchi, C.; Rubiolo, P.; Sgorbini, B. Essential oil composition and in vitro biological activities of seven Namibian species of Eriocephalus L. (Asteraceae). JEOR 2006, 18, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Damjanoviæ-Vratnica, B.; Dakov, T. ; Šukoviæ, D.; Damjanoviæ, J. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oil of wildgrowing Salvia officinalis L. from Montenegro. JEOBP 2008, 11, 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kelen, M.; Tepe, B. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of the essential oils of three Salvia species from Turkish flora. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 4096–4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croteau, R.; Hooper, C.L.; Felton, M. Biosynthesis of monoterpenes. Partial purification and characterization of a bicyclic monoterpenol dehydrogenase from sage (Salvia officinalis). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1979, 188, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croteau, R.; Karp, F. Biosynthesis of monoterpenes: Preliminary characeterisation of bornyl pyrophosphate synthetase from sage (Salvia officinalis) and demonstration that geranyl pyrophosphate is the preferred substrate for cyclization. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1979, 198, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croteau , R.; Karp, F. Biosythesis of monoterpenes: Hydrolysis of bornyl pyrophosphate, an essential step in camphor biosynthesis, and hydrolysis of geranyl pyrophosphate, the acyclic precursor of camphor, by enzymes from sage (Salvia officinalis). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1979, 198, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croteau, R.; Felton, M.; Karp, F.; Kjonaas, R. Relationship of camphor biosynthesis to leaf development in sage (Salvia officinalis). Plant Phys. 1981, 67, 820–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Guo, P.; Liu, G. Asymmetric Synthesis X: The high enantioselective synthesis of (R)-α-substituted benzylic amines via the modified (+)-camphor derivative as chiral synthon. Synth. Commun. 1990, 20, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, R.V.; Gaeta, C.A. Camphorae: Chiral intermediates for the total synthesis of steroids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 6105–6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Du, P.; Sun, Y.; Lin, L.; Liu, Y. Synthesis of vitcamphor derivatives of camphor and its preliminary anti-inflammatory activity. HHBE 2011, 6027903, 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Magiatis, P.; Skaltsounis, A.L.; Chinou, I.; Haroutounian, S.A. Chemical composition and in vitro antimicrobial activity of the essential oils of three Greek Achillea species. Z. Naturforsch. C 2002, 57, 287–290. [Google Scholar]

- De Heluani, C.S.; de Lampasona, M.P.; Vega, M.I.; Catalan, C.A.N. Antimicrobial activity and chemical composition of the leaf and root oils from Croton hieronymi Griseb. JEOR 2005, 17, 351–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Yang, Y.; Yu, H.; Ying, Y.; Zou, G. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oils of Chrysanthemum indicum. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 96, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotan, R.; Kordali, S.; Cakir, A.; Kesdek, M.; Kaya, Y.; Kilic, H. Antimicrobial and insecticidal activities of essential oil isolated from Turkish Salvia hydrangea DC: Ex Benth. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2008, 36, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setzer, W.N.; Vogler, B.; Schmidt, J.M.; Leahy, J.G.; Rives, R. Antimicrobial activity of Artemisia douglasiana leaf essential oil. Fitoterapia 2004, 75, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soković, M.; van Griensven, L.J.L.D. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils and their components against the three major pathogens of the cultivated button mushroom, Agaricus bisporus. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2006, 116, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivropoulou, A.; Nikolaou, C.; Papanikolaou, E.; Kokkini, S.; Lanaras, T.; Arsenakis, M. Antimicrobial, cytotoxic and antiviral activities of Salvia fruticosa essential oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 3197–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo, S.; Cavero, S.; Jaime, L.; Ibañez, E.; Señoráns, F.J.; Reglero, G. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of Rosmarinus officinalis L. essential oil obtained via supercritical fluid extraction. J. Food Prot. 2005, 68, 790–795. [Google Scholar]

- Sökmen, A.; Vardar-Ünlü, G.; Polissiou, M.; Daferera, D.; Sökmen, M.; Dönmez, E. Antimicrobial activity of essential oil and methanol extracts of Achillea sintenisii Hub. Mor. (Asteraceae). Phytother. Res. 2003, 17, 1005–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mevy, J.P.; Bessiere, J.M.; Dherbomez, M.; Millogo, J.; Viano., J. Chemical composition and some biological activities of the volatile oils of a chemotype of Lippia chevalieri Moldenke. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 682–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, B.; Simard, R.E.; Holley, R.A.; Piette, G.J.P.; Bégin, A. Antibacterial activity of selected fatty acids and essential oils against six meat spoilage organisms. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1997, 37, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabanca, N.; Demirci, B.; Başer, K.H.C.; Aytac, Z.; Ekici, M.; Khan, S.I.; Jacob, M.R.; Wedge, D.E. Chemical composition and antifungal activity of Salvia macrochlamys and Salvia recognita essential oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 6593–6597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Logu, A.; Loy, G.; Pellerano, M.L.; Bonsiqnore, L.; Schivo, M.L. Inactivation of HSV-1 and HSV-2 and prevention of cell-to-cell virus spread by Santolina insularis essential oil. Antiviral Res. 2000, 48, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrow, A.; Eccles, R.; Jones, A.S. The effects of camphor, eucalyptus and menthol vapour on nasal resistance to airflow and nasal sensation. Acta Otolaryngol. 1983, 96, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laude, E.A.; Morice, A.H.; Grattan, T.J. The antitussive effects of menthol, camphor and cineole in conscious guinea-pigs. Pulm. Pharmacol. 1994, 7, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKemy, D.D.; Neuhausser, W.M.; Julius, D. Identification of a cold receptor reveals a general role for TRP channels in thermosensation. Nature 2002, 416, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKemy, D.D. How cold is it? TRPM8 and TRPA1 in the molecular logic of cold sensation. Mol. Pain 2005, 1, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Nepali, K.; Sapra, S.; Bijjem, K.R.V.; Kumar, R.; Suri, O.P.; Dhar, K.L. Effect of nitrogen insertion on the antitussive properties of menthol and camphor. Med. Chem. Res. 2012, 21, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.G. Sensory characteristics of camphor. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1990, 94, 662–666. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Blair, N.T.; Clapham, D.E. Camphor activates and strongly desensitizes the transient receptor potential vanilloid subtype 1 channel in a vanilloid-independent mechanism. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 8924–8937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.D., Jr. The use of California sagebrush (Artemisia californica) liniment to control pain. Pharmaceuticals 2012, 5, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanta, V.K.; Hiramoto, N.S.; Solvason, H.B.; Tyring, S.K.; Spector, N.H.; Hiramoto, R.N. Conditioned enhancement of natural killer cell activity, but not interferon, with camphor or saccharin-LiCl conditioned stimulus. J. Neurosci. Res. 1987, 18, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Welsch, C.W.; Rao, A.R. Modulatory influence of camphor on the activities of hepatic carcinogen metabolizing enzymes and the levels of hepatic and extrahepatic reduced glutathione in mice. Cancer Lett. 1995, 88, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, H.C.; Roa, A.R. Radiosensitizing effect of camphor on transplantable mammary adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Lett. 1988, 43, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, H.C.; Singh, S.; Singh, S.P. Radiomodifying influence of camphor on sister-chromatid exchange induction in mouse bone marrow. Mutat. Res. 1989, 224, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanematsu, N.; Shibata, K.I. Investigation of DNA reactivity of endodontic agents by rec-assay. Gifu Shika Gakkai Zasshi 1990, 17, 592–597. [Google Scholar]

- Simić, D.; Vuković-Gacić, B.; Knezević-Vukcević, J. Detection of natural bioantimutagens and their mechanisms of action with bacterial assay-system. Mutat. Res. 1998, 402, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković-Gacić, B.; Nikcević1, S.; Berić-Bjedova, T.; Knezević-Vukcević, J.; Simić, D. Antimutagenic effect of essential oil of sage (Salvia officinalis L.) and its monoterpenes against UV-induced mutations in Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2006, 44, 1730–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, B.; Mitić-Ćulafić, D.; Vuković-Gacić, B.; Knezević-Vukcević, J. Modulation of genotoxicity and DNA repair by plant monoterpenes camphor, eucalyptol and thujone in Escherichia coli and mammalian cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 2035–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Oliveira, A.C.; Ribeiro-Pintob, L.F.; Paumgartten, F.J.R. In vitro inhibition of CYP2B1 monooxygenase by beta-myrcene and other monoterpenoid compounds. Toxicol. Lett. 1997, 92, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methyl bromide technical options committee (MBTOC): Assessment of alternatives to methyl bromide. Nairobi, Kenya, United Nations Environment Programme, Ozone Secretariat. 1998. Available online: http://ozone.unep.org/Assessment_Panels/TEAP/Reports/MBTOC/MBTOC-Assesment-Report-2010.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2013).

- Li, Y.S.; Zou, H.Y. Insecticidal activity of extracts from. Eupatorium adenophorum against four stored grain insects. Entomol. Knowl. 2001, 38, 214–216. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, W.J.; Dória, G.A.A.; Maia, R.T.; Nunes, R.S.; Carvalho, G.A.; Blank, A.F.; Alves, P.B.; Marçal, R.M.; Cavalcanti, S.C.H. Effects of essential oils on Aedes aegypti larvae: Alternatives to environmentally safe insecticides. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 3251–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, R.H. The biochemical ecology of higher plants. In Chemical Ecology; Sondheimer, E., Simeone, J.B., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1970; pp. 43–70. [Google Scholar]

- Brattsten, L.B. Cytochrome P-450 involvement in the interactions between plant terpenes and insect herbivores. In Plant Resistance to Insects; Hedin, P.A., Ed.; ACS (American Chemical Society): Washington, DC, USA, 1983; pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Obeng-Ofori, D.; Reichmuth, C.H.; Bekele, A.J.; Hassanali, A. Toxicity and protectant potential of camphor, a major component of essential oil of Ocimum kilimandscharicum, against four stored product beetles. Int. J. Pest Manag. 1998, 44, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Bekele, J.; Hassanali, A. Blend effects in the toxicity of the essential oil constituents of Ocimum kilimandscharicum and Ocimum kenyense (Labiateae) on two post-harvest insect pests. Phytochemistry 2001, 57, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozman, V.; Kalinovic, I.; Korunic, Z. Toxicity of naturally occurring compounds of Lamiaceae and Lauraceae to three stored-product insects. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2006, 43, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liska, A.; Rozman, V.; Kalinovic, I.; Ivecic, M.; Balicevic, R. Contact and fumigant activity of 1,8-cineole, eugenol and camphor against Tribolium castaneum (Herbst). 2010, 425, 716–720. [Google Scholar]

- Qiantai, L.; Yongcheng, S. Studies on effect of several plant materials against stored grain insects. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Stored-Product Protection; Zuxun, J., Quan, L., Yongsheng, L., Xianchang, T., Lianghua, G., Eds.; Sichuan Publishing House of Science and Technology: Chengdu, China, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 836–844. Available online: http://spiru.cgahr.ksu.edu/proj/iwcspp/pdf2/7/836.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Abivardi, C.; Zareh, N. Effect of camphor on embryonic and postembryonic development of Callosobruchus chinensis. J. Econ. Entomol. 1977, 70, 818–820. [Google Scholar]

- Riddick, E.W.; Aldrich, J.R.; de Milo, A.; Davis, J.C. Potential for modifying the behavior of the multi-colored Asian lady beetle (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) with plant-derived natural products. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2000, 93, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojimelukwe, P.C.; Adler, C. Toxicity and repellent effects of eugenol, thymol, linalool, menthol and other pure compounds on Dinoderus bifloveatus (Coleoptera: Bostrichidae). J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2000, 2, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Prates, H.T.; Leite, R.C.; Craveiro, A.A.; Oliveira, A.B. Identification of some chemical components of the essential oil from molasses grass (Melinis minutiflora Beauv.) and their activity against cattle-tick (Boophilus microplus). J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 1998, 9, 993–997. [Google Scholar]

- Arlian, L.G. Arthropod allergens and human health. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2002, 47, 395–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.C.; Jang, Y.S.; Hieu, T.T.; Lee, C.K.; Ahn, Y.J. Toxicity of Myristica fragrans seed compounds against B. germanica (Dictyoptera: Blattellidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2007, 44, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlit, A.M.; Lopes, N.P.; Gama, R.A.; Tadei, W.P.; de Andrade Neto, V.F. Patent literature on mosquito repellent inventions which contain plant essential oils—A review. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 598–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briassoulis, G.; Narlioglou, M.; Hatzis, T. Toxic encephalopathy associated with use of DEET insect repellents: A case analysis of its toxicity in children. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2001, 20, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillij, Y.G.; Gleiser, R.M.; Zygadlo, J.A. Mosquito repellent activity of essential oils of aromatic plants growing in Argentina. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 2507–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.A.; Razdan, R.K. Relative efficacy of various oils in repelling mosquitoes. Indian J. Malariol. 1995, 32, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Seyoum, A.; Palsson, K.; Kung’a, S.; Kabiru, E.W.; Lwande, W.; Killeen, G.F.; Hassanali, A.; Knols, B.G. Traditional use of mosquito-repellent plants in western Kenya and their evaluation in semi-field experimental huts against Anopheles gambiae: Ethnobotanical studies and application by thermal expulsion and direct burning. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002, 96, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyoum, A.; Killeen, G.F.; Kabiru, E.W.; Knolls, B.G.J.; Hassanali, A. Field efficacy of thermally expelled or live potted repellent plants against African malaria vectors in western Kenya. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2003, 8, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, O.T. Camphor and strychnine as cardiac stimulants. JAMA 1928, 90, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, G.G.; Breithaupt-Grögler, K.; Butzer, R.; Herrmann, V.; Malerczyk, C.; Mang, C.; Roll, S. Klinische pharmakologie von D-Campher. In Phytopharmaka VI; Rietbrock, N., Ed.; Steinkopff Verlag: Darmstadt, Germany, 2000; pp. 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Belz, G.G.; Loew, D. Dose-response related efficacy in orthostatic hypotension of a fixed combination of D-camphor and an extract from fresh Crataegus berries and the contribution of the single components. Phytomedicine 2003, 10 (Suppl. 4), 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.C.; Barry, B.W. Terpenes and the lipid-protein-partitioning theory of skin penetration enhancement. Pharmaceut. Res. 1991, 8, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, T.; Kanetake, T.; Saita, M.; Noda, K. Effects of l-menthol and dl-camphor on the penetration and hydrolysis of methyl salicylate in hairless mouse skin. J. Pharmacobiodyn 1991, 14, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.Y.; Tsai, T.H.; Lin, Y.Y.; Wong, W.W.; Wang, M.N.; Huang, J.F. Transdermal delivery of tea catechins and theophylline enhanced by terpenes: A mechanistic study. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, G.; Vamshi, V.Y.; Kishan, V.; Madhusudan, R.Y. Studies on the influence of penetration enhancers on in vitro permeation of carvedilol across rat abdominal skin. Curr. Trends Biotechnol. Pharm. 2007, 1, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, R.; Aqil, M.; Ahad, A.; Ali, A.; Khar, R.K. Basil oil is a promising skin penetration enhancer for transdermal delivery of labetolol hydrochloride. Drug Develop. Ind. Pharm. 2008, 34, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Sheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, J. Effect of menthol and camphor on permeation of compound diphenhydramine cream in vitro. Cent. South Pharm. 2011, 2, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Jamshidzadeh, A.; Sajedianfard, J.; Nekooeian, A.A.; Tavakoli, F.; Omrani, G.H. Effects of Camphor on Sexual Behaviors in Male Rats. IJPS 2006, 2, 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Nikravesh, M.R.; Jalali, M. The effect of camphor on the male mice reproductive system. Urol. J. 2004, 1, 268–272. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, P.C.; Lydon, J.; Danforth, H.D. Effects of components of Artemisia annua on coccidia infections in chickens. Poult Sci. 1997, 76, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar]

- Tariku, Y.; Hymete, A.; Hailu, A.; Rohloff, J. In vitro evaluation of antileishmanial activity and toxicity of essential oils of Artemisia absinthium and Echinops kebericho. Chem. Biodivers. 2011, 8, 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, J.R. Phytochemistry, allelopathy and the capability attributes of camphor laurel (Cinnamomum camphora (L.) Ness & Eberm.). Ph.D. Thesis, Southern Cross University, Lismore, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, Y.; Yamahi, K.; Kobayashi, K. Allelopathic activity of camphor released from camphor tree (Cinnamomum camphora). Allelopathy J. 2011, 27, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- De Martino, L.; Mancini, E.; de Almeida, L.F.R.; de Feo, V. The antigerminative activity of twenty-seven monoterpenes. Molecules 2010, 15, 6630–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, J.M. Poisoning: Toxicology, Symptoms, Treatments, 4th ed.; CC. Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Rabl, W.; Katzgraber, F.; Steinlechner, M. Camphor ingestion for abortion (case report). Forensic Sci. Int. 1997, 89, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International program on chemical safety (IPCS) INCHEM. Camphor. Available online: http://www.inchem.org/documents/pims/pharm/camphor.htm/ (accessed on 1 December 2012).

- Love, J.N.; Sammon, M.; Smereck, J. Are one or two dangerous? Camphor exposure in toddlers. J. Emerg. Med. 2003, 27, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, W.J. Camphor poisoning: Over-the-counter dangers. Pediatrics 1976, 57, 428–431. [Google Scholar]

- Theis, J.G.; Koren, G. Camphorated oil: Still endangering the lives of Canadian children. CMAJ 1995, 152, 1821–1824. [Google Scholar]

- Manoguerra, A.S.; Erdman, A.R.; Wax, P.M.; Nelson, L.S.; Caravati, E.M.; Cobaugh, D.J.; Chyka, P.A.; Olson, K.R.; Booze, L.L.; Woolf, A.D.; et al. Camphor Poisoning: An evidence-based practice guideline for out-of-hospital management. Clin. Toxicol. 2006, 44, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzung, G.B. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology, 7th ed.; Appleton and Lange: Stamford, CT, USA, 1998; pp. 372–375. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin, R.E.; Smith, R.P.; Hodge, H.C. Clinical Toxicology of Commercial Products, 5th ed.; Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Park, T.; Seo, H.; Kang, B.; Kim, K. Noncompetitive inhibition by camphor of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001, 61, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, J.; Hamilton, R.; Homel, S.; McCabe, J. Camphorated oil intoxication in pregnancy; report of a case. Obstet. Gynecol. 1965, 25, 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- Leuschner, J. Reproductive toxicity studies of d-camphor in rats and rabbits. Arzneim. Forsch. 1997, 47, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Enaibe, B.; Eweka, A.; Adjene, J. Toxicological effects of camphor administration on the histology of the kidney of the rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Internet J. Toxicol. 2008, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahook, M.Y.; Thomas, S.A.; Ciardella, A.P. Central serous chorioretinopathy associated with chronic dermal camphor application. Internet J. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 4, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Millet, Y.; Jouglard, J.; Steinmetz, M.D.; Tognetti, P.; Joanny, P.; Arditti, J. Toxicity of some essential plant oils. Clinical and experimental study. Clin. Toxicol. 1981, 18, 1485–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, W.; Vermaak, I.; Viljoen, A. Camphor—A Fumigant during the Black Death and a Coveted Fragrant Wood in Ancient Egypt and Babylon—A Review. Molecules 2013, 18, 5434-5454. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules18055434

Chen W, Vermaak I, Viljoen A. Camphor—A Fumigant during the Black Death and a Coveted Fragrant Wood in Ancient Egypt and Babylon—A Review. Molecules. 2013; 18(5):5434-5454. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules18055434

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Weiyang, Ilze Vermaak, and Alvaro Viljoen. 2013. "Camphor—A Fumigant during the Black Death and a Coveted Fragrant Wood in Ancient Egypt and Babylon—A Review" Molecules 18, no. 5: 5434-5454. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules18055434