General

Optical rotations were determined with a Perkin-Elmer 343 model polarimeter at the sodium D line at 20 °C.

1H-NMR spectra and and

13C-NMR were recorded at the frequencies stated. Chemical shifts are reported relative to internal Me

4Si (δ 0.0) in CDCl

3 or CDCl

3-MeOD, or HOD for D

2O (δ 4.84) or CD

2HOD (δ 3.31) for

1H and Me

4Si in CDCl

3 (δ 0.0) or CDCl

3 (δ 77.0) or CD

3OD (δ 49.05) for

13C.

1H- NMR signals were assigned with the aid of COSY.

13C-NMR signals were assigned with the aid of DEPT, HSQC and/or HMBC. Coupling constants are reported in hertz. The IR spectra were recorded as thin films between NaCl plates or with an ATR attachment. Low and high resolution mass spectra were measured on either a micromass VG 70/70H or VG ZAB-E or Waters LCT premiere XE spectrometers and were measured in positive and/or negative mode. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on aluminium sheets precoated with silica gel and spots visualized by UV and charring with H

2SO

4-EtOH (1:20) or cerium molybdate. Flash chromatography was carried out with silica gel 60 (0.040–0.630 mm). Chromatography solvents were used as obtained from suppliers. CH

2Cl

2, MeOH, and THF reaction solvents were dried using a Pure Solv™ Solvent Purification System and acetonitrile, DMF, pyridine, and toluene were used as purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The experimental details for the preparation of

6,

7,

9,

13,

14,

16–

18,

19b–

24b,

35,

38,

42,

43,

44 and

46b and their analytical data have been reported previously [

13,

14].

1,2,3,4-Tetra-O-benzoyl-α-D-galactopyranuronic acid, allyl ester (

20a).

d-Galactose (5.4 g, 0.03 mol) and trityl chloride (17.0 g, 0.04 mol) were dried under diminished pressure for 3 h. The mixture was taken up in pyridine (80 mL) and heated at 90 °C for 16 h, then The solution was then cooled to 0 °C and benzoyl chloride (17 mL, 0.15 mol) was added slowlyand he reaction mixture was then allowed to attain room temp, stirred for 20 h, and the mixture was then diluted with CH

2Cl

2 and washed with water, 2 M HCl, satd aq NaHCO

3, brine, dried over Na

2SO

4 and the solvent was removed under diminished pressure. The resulting syrup was dissolved in CH

2Cl

2-MeOH (1:2, 150 mL) and conc. H

2SO

4 (15 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred for 1 h at room temp and then washed with water, satd aq NaHCO

3, brine, and dried over Na

2SO

4, and the solvent was removed under diminished pressure. Flash chromatography (petroleum ether-EtOAc, 4:1) gave

19a as a white solid and a mixture of anomers (10.9 g, 61%). The NMR data (

1H and

13C) for

19a were in agreement with data reported in the literature [

36]. To

19a (10.0 g, 0.017 mol) in CH

2Cl

2 (100 mL) and H

2O (40 mL) were added TEMPO (0.5 g) and BAIB (16.2 g, 0.05 mol). The mixture was stirred vigorously for 2 h and satd Na

2S

2O

3 (40 mL) was then added and the resulting mixture stirred for 15 min. The layers were separated and the aq phase acidified with 1M HCl and extracted with CH

2Cl

2 (×3). The combined organic layers were dried over Na

2SO

4, and the solvent was removed under diminished pressure to give the galacturonic acid intermediate (9.5 g, 91%). The resulting solid was dissolved in THF (100 mL), to this K

2CO

3 (115 mg, 0.84 mmol), 18-crown-6 (10 mg) and allyl iodide (140 mg, 0.84 mmol, 80 µL) were added. The reaction was stirred in the dark for 16 h at room temp. The reaction mixture was diluted with Et

2O, washed with water, sodium thiosulfate, water, brine, dried over MgSO

4. The solvent was then removed under reduced pressure and then flash chromatography (EtOAc-cyclohexane 1:4) of the residue gave

20a (484 mg, 44%) as a white solid; R

f 0.53 (EtOAc-cyclohexane 2:5); [α]

D +87 (

c 4.7, CHCl

3); IR (film) cm

−1: 3065, 2930, 1733, 1451, 1263, 1092, 1069;

1H-NMR (CDCl

3, 400 MHz ): δ 8.05 (4H, m, aromatic H), 7.89 (2H, dd,

J = 7.2 Hz,

J = 1.3 Hz, aromatic H), 7.83 (2H, dd,

J = 7.2,

J = 1.3 Hz, aromatic H), 7.61 (1H, tt,

J = 7.5 Hz,

J = 1.2 Hz, aromatic H), 7.56 (1H, tt,

J = 7.4,

J = 1.2 Hz, aromatic H), 7.45 (6H, m, aromatic H), 7.30 (4H, m, aromatic H), 6.28 (2H, m, H-1, H-4), 6.01 (1H, dd,

J = 10.3 Hz,

J = 8.3 Hz, H-2), 5.79 (1H, dd,

J = 10.3 Hz,

J = 3.5 Hz, H-3), 5.72 (1H, ddt,

J = 17.2 Hz,

J = 10.3 Hz,

J = 6.1 Hz, C

H=CH

2), 5.22 (1H, dd,

J = 17.2 Hz,

J = 1.3 Hz, CH=C

H2), 5.07 (1H,

J = 10.3 Hz,

J = 1.0 Hz, CH=C

H2), 4.86 (1H, d,

J = 1.5 Hz, H-5), 4.59 (2H, m, OC

H2CH=CH

2);

13C-NMR (CDCl

3, 100 MHz): δ 165.4, 165.2, 165.1, 165.0 164.7 (each C=O), 133.8, 133.6, 133.4 (2s), 130.7, 130.3, 130.1, 129.8, 129.7, 128.8, 128.7, 128.6, 128.5, 128.4 (3s), 128.3 (each C or CH), 120.0 (alkene CH

2) 92.6 (C-1), 73.7 (C-5), 71.2 (C-3), 69.0 (C-4), 68.2 (C-2), 66.7 (O

CH

2CH=CH

2); ESI-HRMS calcd for C

37H

30O

11Na 673.1686, found

m/z 673.1714 [M+Na]

+.

2,3,4-Tri-O-benzoyl-1-deoxy-1-(2,2,2-trichloro-1-iminoethoxy)-α-d-galactopyranuronic acid,allyl ester (11). Allyl ester 20a (325 mg, 0.50 mmol) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (3 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. To this HBr 33% in AcOH (2 mL) was added and the reaction stirred at room temp for 3 h. The reaction was quenched with satd NaHCO3), washed with water, brine, dried over MgSO4, and the solvent removed under reduced pressure to give the intermediate bromide (237 mg, 78%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 7.99 (4H, d, J = 7.4 Hz, aromatic H), 7.82 (2H, d, J = 7.4 Hz, aromatic H), 7.61 (1H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, aromatic H), 7.54 (1H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, aromatic H), 7.46 (3H, m, aromatic H), 7.39 (2H, t, J = 7.8 Hz, aromatic H), 7.28 (2H, t, J = 7.8 Hz, aromatic H), 7.02 (1H, d, J = 3.9 Hz, H-1), 6.32 (1H, dd, J = 3.2 Hz, J = 1.3 Hz, H-4), 6.05 (1H, dd, J = 10.5 Hz, J = 3.2 Hz, H-3), 5.75 (1H, ddt, J = 17.1 Hz, J = 10.5 Hz, J = 6.1 Hz, CH=CH2), 5.66 (1H, dd, J = 10.5 Hz, J = 3.9 Hz, H-2), 5,24 (1H, dd, J = 17.1 Hz, J = 0.8 Hz, J = CH=CH2), 5.17 (1H, d, J = 1.3 Hz, H-5), 5.10 (1H, d, J = 10.3 Hz, CH=CH2), 4.60 (2H, m, OCH2CH=CH2); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ 165.4, 165.3, 165.0, 164.9 (each C=O), 133.9, 133.7, 133.4, 130.5, 130.0, 129.9, 129.7 (3s), 128.6, 128.5, 128.4, 128.3 (each C or CH), 120.2 (alkene CH2), 87.4 (C-1), 72.9 (C-5), 68.7 (C-4), 68.6 (C-3), 67.9 (C-2), 66.8 (OCH2CH=CH2). This bromide (237mg, 0.39 mmol) was dissolved in acetone (18 mL) and H2O (2 mL). To this Ag2CO3 (64 mg, 0.23 mmol) was added and the reaction stirred in the dark at room temp for 24 h. The reaction mixture was filtered through celite, which was rinsed with CH2Cl2. The filtrate was washed with water, brine, dried over MgSO4, and the solvent removed under reduced pressure. Flash chromatography (EtOAc-cyclohexane 2:5) gave the hemiacetal (164 mg, 77%) as a colourless oil; Rf 0.18 (EtOAc-cyclohexane 2:5); IR (film) cm−1: 3446, 3069, 2961, 1730, 1264, 1094, 1070, 1026; ES-HRMS calcd for C30H27O10 547.1604, found m/z 547.1612 [M+H]+; NMR data for the α anomer: 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 8.00-7.26 (15H, ms, aromatic H), 6.30 (1H, dd, J = 3.5 Hz, J = 1.6 Hz, H-4), 6.08 (1H, dd, J = 10.7 Hz, J = 3.5 Hz, H-3), 5.96 (1H, t, 3.6 Hz, H-1), 5.70 (2H, overlapping signals, H-2 & CH=CH2), 5.22 (1H, dd, J = 17.2 Hz, J = 1.3 Hz, CH=CH2), 5.18 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz, H-5), 5.06 (1H, dd, J = 10.4 Hz, J = 1.1 Hz, CH=CH2), 4.62 (1H, dd, J = 12.5 Hz, J = 6.5 Hz, OCH2CH=CH2), 4.55 (1H, dd, J = 12.5 Hz, J = 6.3 Hz, OCH2CH=CH2), 4.16 (1H, d, J = 3.6 Hz, OH); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ 167.3, 165.9, 165.6, 165.2 (each C=O), 133.5, 133.4, 133.1, 130.7, 129.9, 129.8 (2s), 129.7, 129.1 (2s), 129.0, 128.5, 128.4, 128.2, 119.9 (alkene CH2), 91.2 (C-1), 69.9 (C-4), 68.8 (2s, C-2 & C-5), 67.7 (C-3), 66.5 (OCH2CH=CH2); selected NMR data for the β anomer: 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 6.22 (1H, dd, J = 3.4 Hz, J = 1.5 Hz, H-4), 5.29 (1H, s), 4.68 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz), 4.30 (1 H, d, J = 8.3 Hz, OH); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ 166.6, 165.9, 165.5, 165.1 (each C=O), 120.0 (alkene CH2), 96.1 (C-1), 73.0 (C-5), 71.4 (C-2), 70.7, 69.0, 66.7 (OCH2CH=CH2). This hemiacetal (166 mg, 0.30 mmol) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (6 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. To this trichloroacetonitrile (0.3 mL, 3.0 mmol) and DBU (5 drops) were added, and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 4 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to a volume of 2 mL and flash chromatography (EtOAc-cyclohexane 1:4) then gave 11 (133 mg, 63%) as a yellow oil; Rf 0.34 (EtOAc-cyclohexane 2:5); IR (film) cm−1: 3328, 3072, 2958, 1735, 1677, 1452, 1265, 1106, 1068, 1027, 709; 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ 8.69 (1H, s, NH), 8.02 (2H, d, J = 7.2 Hz, aromatic H), 7.94 (2H, J = 7.2 Hz, aromatic H), 7.82 (2H, d, J = 7.2 Hz, aromatic H), 7.60 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, aromatic H), 7.46 (4H, m, aromatic H), 7.34 (2H, t, J = 7.8 Hz, aromatic H), 7.27 (2H, t, J = 7.8Hz, aromatic H), 7.05 (1H, d, J = 3.5 Hz, H-1), 6.37 (1H, dd, J = 3.3 Hz, J = 1.4 Hz, H-4), 6.10 (1H, dd, J = 10.7 Hz, J = 3.3 Hz, H-3), 5.96 (1H, J = 10.7 Hz, J = 3.5 Hz, H-2), 5.75 (1H, ddt, J = 17.1 Hz, J = 10.4, J = 6.1 Hz, CH=CH2), 5.22 (1H, dd, J = 17.1 Hz, J = 1.2 Hz, CH=CH2), 5.11 (1H, d, J = 1.4 Hz, H-5), 5.07 (1H, dd, J = 10.4 Hz, J = 0.7 Hz, CH=CH2), 4.62 (1H, dd, J = 12.7 Hz, J = 6.1 Hz, OCH2CH=CH2), 4.56 (1H, dd, J = 12.7 Hz, J = 6.1 Hz, OCH2CH=CH2); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz): δ 165.6, 165.4, 165.4, 165.0 (each C=O), 160.2 (C=N), 133.6, 133.5, 133.3, 130.7, 129.9, 129.8, 129.7, 128.8 (2s), 128.6, 128.5, 128.4, 128.3, 120.0 (CH=CH2), 93.6 (C-1), 71.2 (C-5), 69.4 (C-4), 67.8 (C-3), 67.3 (C-2), 66.6 (OCH2CH=CH2); ES-HRMS calcd for C32H26O10NCl3Na 712.0520, found m/z 712.0545 [M+Na]+.

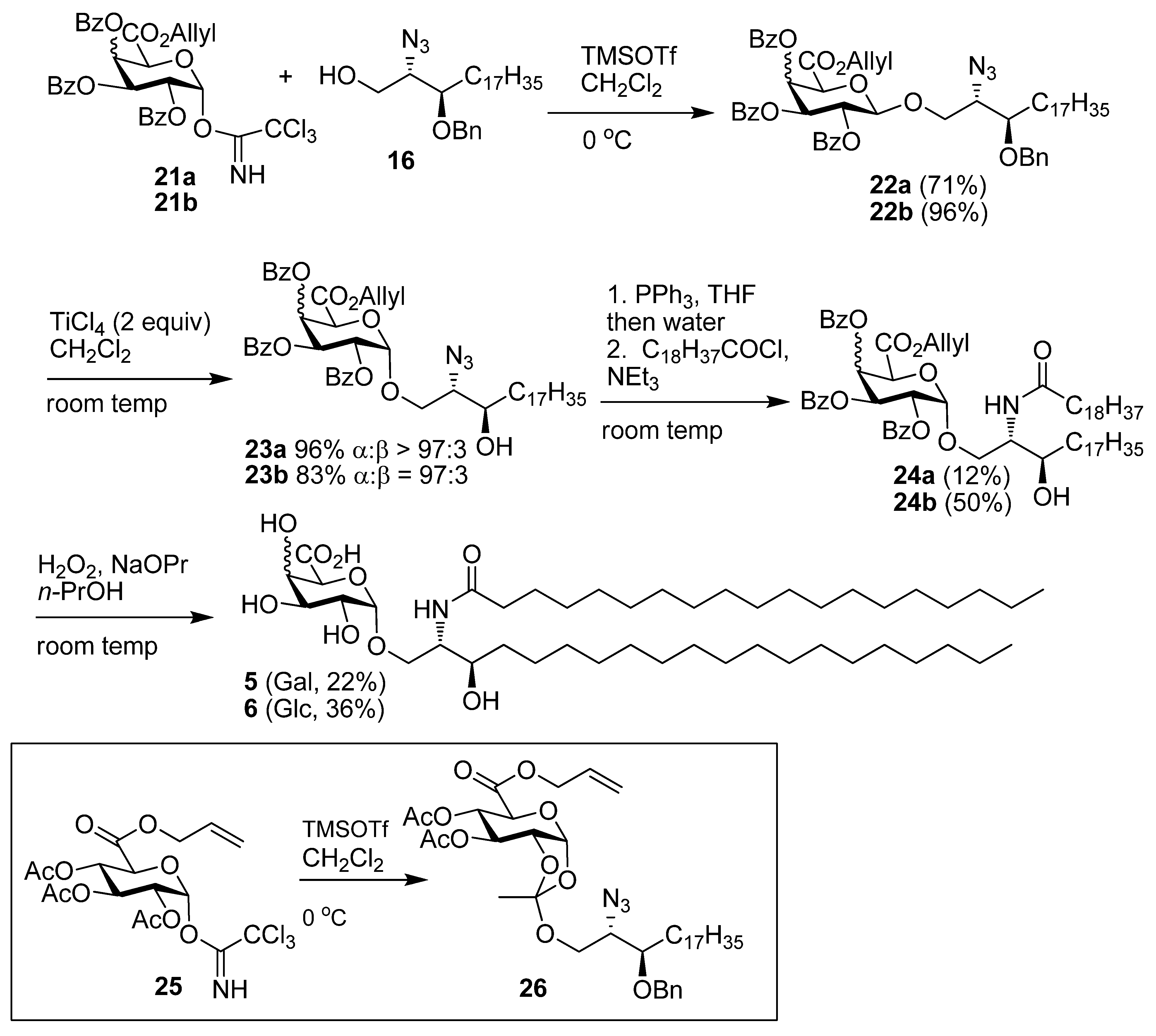

((2S,3R)-2-Azido-3-benzyloxyicosanyl) 2,3,4-tri-O-benzoyl-β-d-galactopyranuronic acid, allyl ester (22a). Alcohol 16 (78 mg, 0.18 mmol) and imidate 11 (133 mg, 0.19 mmol) were dissolved in CH2Cl2 (6 mL) and stirred over 4Å MS for 20 min then cooled to 0 °C. To this TMSOTf (0.1M, 0.035 mmol, 0.35 mL) was added and the reaction stirred at 0 °C for 40 min. Solid NaHCO3 (30 mg) was added and the mixture stirred for 20 min and then filtered through celite, which was rinsed with CH2Cl2. The solvent was then removed under reduced pressure and flash chromatography (EtOAc-cyclohexane 1:4) gave 22a (127 mg, 75%) as a yellow oil; Rf 0.50 (EtOAc-cyclohexane 2:5); [α]D +76 (c 6.6 ,CHCl3); IR (film) cm−1: 3064, 2924, 2853, 2099, 1734, 1261, 1108; 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ 7.99 (2H, dd, J = 8.3 Hz, J = 1.1 Hz, aromatic H), 7.95 (2H, J = 8.3 Hz, J = 1.1 Hz, aromatic H), 7.81 (2H, J = 8.3 Hz, J = 1.1 Hz, aromatic H), 7.56 (1H, tt, J = 7.5 Hz, J = 1.2 Hz, aromatic H), 7.50 (1H, tt, J = 7.4 Hz, J = 1.2 Hz, aromatic H), 7.43 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, aromatic H), 7.36 (8H, m, aromatic H), 7.26 (3H, m, aromatic H), 6.21 (1H, dd, J = 3.5 Hz, J = 1.2 Hz, H-4), 5.82 (1H, dd, J = 10.4 Hz, J = 7.9 Hz, H-2), 5.75 (1H, ddt, J = 17.2 Hz, J = 10.3 Hz, J = 6.0 Hz, CH=CH2), 5.63 (1H, dd, J = 10.4 Hz, J = 3.5 Hz, H-3), 5.23 (1H, dd, J = 17.2 Hz, J = 1.3 Hz, CH=CH2), 5.07 (1H, dd, J = 10.3 Hz, J = 1.0 Hz, CH=CH2), 4.91 (1H, d, J = 7.9 Hz, H-1), 4.58–4.64 (3H, overlapping signals, BnCHH, H-5, OCH2CH=CH2) 4.56 (1H, ddt, J = 13.0 Hz, J = 6.0 Hz, J = 1.0 Hz, OCH2CH=CH2), 4.46 (1H, d, 11.3 Hz, BnCHH), 4.25 (1H, dd, J = 10.7 Hz, J = 5.6 Hz, CHHO), 3.81 (1H, dd, J = 10.7 Hz, J = 5.0 Hz, CHHO), 3.70 (1H, dd, J = 10.7 Hz, J = 5.4 Hz, CHN3), 3.50 (1H, ddd, J = 3.5 Hz, J = 5.5 Hz, J = 8.0 Hz, CHOBn), 1.45 (2H, m, CH2), 1.27 (30H, s, 15 CH2), 0.88 (3H, t, J = 6.9 Hz, CH3); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz): δ 165.5, 165.4, 165.1, 165.0 (each C=O), 138.2, 133.4, 133.3, 133.2, 130.9, 130.0, 129.8, 129.7, 129.2, 128.9, 128.7, 128.5, 128.3 (3s), 128.0, 127.6, 119.7 (CH=CH2), 101.3 (C-1), 78.3 (CHOBn), 72.9 (C-5), 72.7 (BnCH2), 71.3 (C-3), 69.2 (C-2), 69.0 (C-4), 68.9 (CH2O), 66.5 (OCH2CH=CH2), 63.1 (CHN3), 31.9, 30.7 (3s), 29.6 (2s), 29.5 (2s), 29.3, 26.9, 25.0, 22.6 (each CH2), 14.1 (CH3); ES-HRMS calcd for C57H71O11N3Na 996.4986, found m/z 996.4960 [M+Na]+.

((2S,3R)-2-Azido-3-hydroxyicosanyl) 2,3,4-tri-O-benzoyl-α-D-galactopyranuronic acid, allyl ester (23a). The β-glycoside 22a (125 mg, 0.129 mmol) was dissolved in CHCl3 (6 mL), to this TiCl4 (48 mg, 0.25 mmol, 27 µL) was added and the reaction was stirred at room temp for 3 h. The reaction mixture was poured onto satd NaHCO3-Et2O (1:9) and stirred for 30 min. The mixture was filtered through celite, which was rinsed with Et2O, the organic layer was decanted and dried over MgSO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and then flash chromatography of the residue (EtOAc-cyclohexane 1:9) gave 23a (114 mg, 99%) as a yellow oil; Rf 0.26 (EtOAc-cyclohexane 1:4); [α]D +110 (c 5.7, CHCl3); IR (film) cm−1: 3521, 3068, 2924, 2853, 2098, 1732, 1265, 1094, 1026; 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ 8.00 (4H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, aromatic H), 7.81 (2H, dd, J = 8.4 Hz, J = 1.2 Hz, aromatic H), 7.59 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, aromatic H), 7.51 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, aromatic H), 7.45 (3H, m, aromatic H), 7.37 (2H, t, J = 7.8 Hz, aromatic H), 7.26 (2H, t, J = 7.8 Hz, Hz), 6.28 (1H, dd, J = 3.5 Hz, J = 1.4 Hz, H-4), 6.01 (1H, dd, J = 10.8 Hz, J = 3.5 Hz, H-3), 5.76 (1H, ddt, J = 17.2 Hz, J = 10.4 Hz, J = 6.1 Hz, CH=CH2), 5.70 (1H, dd, J = 10.8 Hz, J = 3.6 Hz, H-2), 5.61 (1H, d, J = 3.6 Hz, H-1), 5.23 (1H, dd, J = 17.2 Hz, J = 1.3 Hz, CH=CH2), 5.08 (1H, dd, J = 10.4 Hz, J = 0.9 Hz, CH=CH2), 4.96 (1H, d, J = 1.4 Hz, H-5), 4.62 (1H, dd, J = 12.7 Hz, J = 6.1 Hz, OCH2CH=CH2), 4.57 (1H, dd, J = 12.7 Hz, J = 6.1 Hz, OCH2CH=CH2), 4.12 (1H, dd, J = 10.6 Hz, J = 2.8 Hz, CHHO), 3.80 (1H, dd, J = 10.6 Hz, J = 6.8 Hz, CHHO), 3.69 (1H, m, CHOH), 3.48 (1H, td, J = 6.5 Hz, J = 2.8 Hz, CHN3), 1.80 (1H, d, J = 4.6 Hz, OH), 1.38 (4H, m, 2 CH2), 1.26 (s, 28H, 14 CH2), 0.88 (3H, t, J = 0.88 Hz, CH3); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz): δ 166.4, 165.9, 165.4, 165.1 (each C=O), 133.5 (2s), 133.2, 130.8, 129.9, 129.8, 129.7, 129.0 (2s), 128.9, 128.5, 128.4, 128.2, 119.9 (alkene CH2), 97.6 (C-1), 71.2 (CHOH), 69.8 (C-4), 69.3, 69.2, 68.5 (C-2), 67.8 (C-3), 66.5 (OCH2CH=CH2), 65.3 (CHN3), 33.7, 31.9, 29.7, 29.6, 29.5 (3s), 29.3, 26.9, 25.5, 22.6 (each CH2), 14.1 (CH3); ES-HRMS calcd for C50H65O11N3Na 906.4517, found m/z 906.4526 [M+Na]+.

((2S,3R)-2-(N-Nonadecanoylamino)-3-hydroxyicosan-1-yl) 2,3,4-tri-O-benzoyl-α-D-galactopyran-uronic acid, allyl ester (24a). Azide 23a (110 mg, 0.125 mmol) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (4 mL) and PBu3 (62 μL, 0.25 mmol) was added. The reaction was stirred at room temp for 1.5 h followed by the addition of H2O (2 mL) and MeOH (0.5 mL) and the reaction stirred for a further 2 h. The reaction was diluted with Et2O, washed with water, brine, dried over MgSO4, and the solvent removed under reduced pressure. The crude amine was take up in CH2Cl2 (4 mL) and cooled to 0 °C, to this DIEPA (48 mg, 0.37 mmol, 65 µL) and nonadecanoyl chloride (0.50 mL of 0.25 mM, 0.125 mmol) were respectively added, and the reaction allowed to attain room temp over 16 h. The reaction mixture was taken up in Et2O, washed with water, brine, dried over MgSO4 and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. Flash chromatography (EtOAc-cyclohexane 1:4) gave 24a (15 mg, 12%) as a white solid; Rf 0.18 (EtOAc-cyclohexane 2:5); IR (film) cm−1: 3309, 2917, 2850, 1731, 1650, 1266, 1094; 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ 8.01 (2H, d, J = 7.2 Hz, aromatic H), 7.96 (2H, d, J = 7.3 Hz, aromatic H), 7.82 (2H, d, J = 7.2 Hz, aromatic H), 7.61 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, aromatic H), 7.54 (1H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, aromatic H), 7.46 (3H, m, aromatic H), 7.40 (2H, t, J = 7.8 Hz, aromatic H), 7.29 (2H, t, J = 7.9 Hz, aromatic H), 6.31 (1H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, NH), 6.26 (1H, dd, J = 3.4 Hz, J = 1.3 Hz, H-4), 5.96 (1H, dd, J = 10.7 Hz, J = 3.4 Hz, H-3), 5.76 (1H, ddt, J = 17.2 Hz, J = 10.3 Hz, J = 6.2 Hz, CH=CH2), 5.68 (1H, dd, J = 10.7 Hz, J = 3.7 Hz, H-2), 5.58 (1H, d, J = 3.7 Hz, H-1), 5.24 (1H, dd, J = 17.2 Hz, J = 1.2 Hz, CH=CH2), 5.10 (1H, dd, J = 10.3 Hz, J = 1.2 Hz, CH=CH2), 4.81 (1H, d, J = 1.3 Hz, H-5), 4.63 (1H, dd, J = 12.8 Hz, J = 6.2 Hz, OCH2CH=CH2), 4.57 (1H, dd, J = 12.8 Hz, J = 6.2 Hz, OCH2CH=CH2), 4.10 (1H, dd, J = 10.4 Hz, J = 2.2 Hz, CHHO), 4.00 (1H, m, CHOH), 3.83 (1H, dd, J = 10.4 Hz, J = 3.6 Hz, CHHO), 3.56 (1H, m, CHN), 2.39 (1H, brs, OH), 2.24 (2H, m, COCH2), 1.62 (4H, m, 2 CH2), 1.27 (60H, br s, 30 CH2), 0.89 (6H, t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 CH3); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz): δ173.2, 166.1, 165.5 (2s), 165.1 (each C=O), 133.8, 133.6, 133.3, 130.8, 130.0, 129.8, 129.7, 128.9 (2s), 128.6 (2s), 128.5, 128.3, 120.0 (alkene CH2), 97.4 (C-1), 73.2 (CHOH), 69.7 (2s), 69.1 (C-5), 68.7 (C-2), 67.8 (C-3), 66.6 (OCH2CH=CH2), 52.1 (CHN), 36.8 (COCH2), 34.9, 31.9, 29.8, 29.7 (4s), 29.6, 29.5 (2s), 29.4 (4s), 26.9, 25.9, 25.8, 22.7 (each CH2), 14.1 (2 × CH3). ES-HRMS calcd for C69H104O12N 1138.7559, found m/z 1138.7515 [M+H]+.

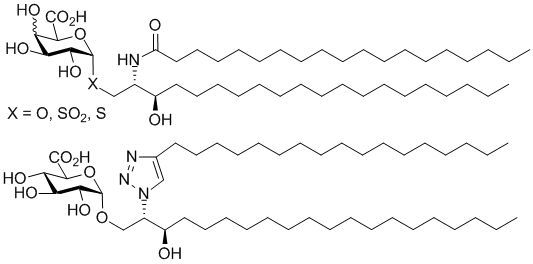

((2S,3R)-2-(N-Nonadecanoylamino)-3-hydroxyicosan-1-yl) α-d-galactopyranuronic acid (5). The protected lipid 24a (8 mg, 7 µmol) was dissolved in n-PrOH (4 mL) and H2O2 (30%, 0.3 mL), and to this nPrONa-nPrOH (0.1 M, 60 µmol, 600 µmL) was added at a rate of 100 µL/h. After the addition was completed, the reaction mixture was then centrifuged at 15000 rpm for 15 min, the supernatant was removed and the precipitate washed twice with water. The precipitate was then lyophilised to give 5 (1.2 mg, 22%) as a white solid; 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ 4.93 (1H, d, J = 2.3 Hz, H-1), 4.26 (1H, s, H-5), 4.22 (1H, m), 3.88 (1H, m, CNH), 3.81 (1H, dd, J = 10.1 Hz, J = 3.0 Hz, H-2), 3.78 (3H, overlapping signals), 3.62 (1H, td, J = 7.2 Hz, J = 1.9 Hz, CHOH), 2.21 (2H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, CH2CO2), 1.64-1.53 (4H, m, CH2), 1.27 (60H, br s, CH2), 0.89 (6H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, CH3); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz): δ 175.1 (C=O), 99.9 (C-1), 72.0 (C-5), 71.0 (C-3), 71.0 (CHOH), 70.8, 68.9, 68.2, 53.7 (CHN), 36.5 (COCH2), 36.7, 32.3, 30.0 (2s), 29.9, 27.8, 29.7 (2s), 26.3, 26.1, 23.0, 14.2.

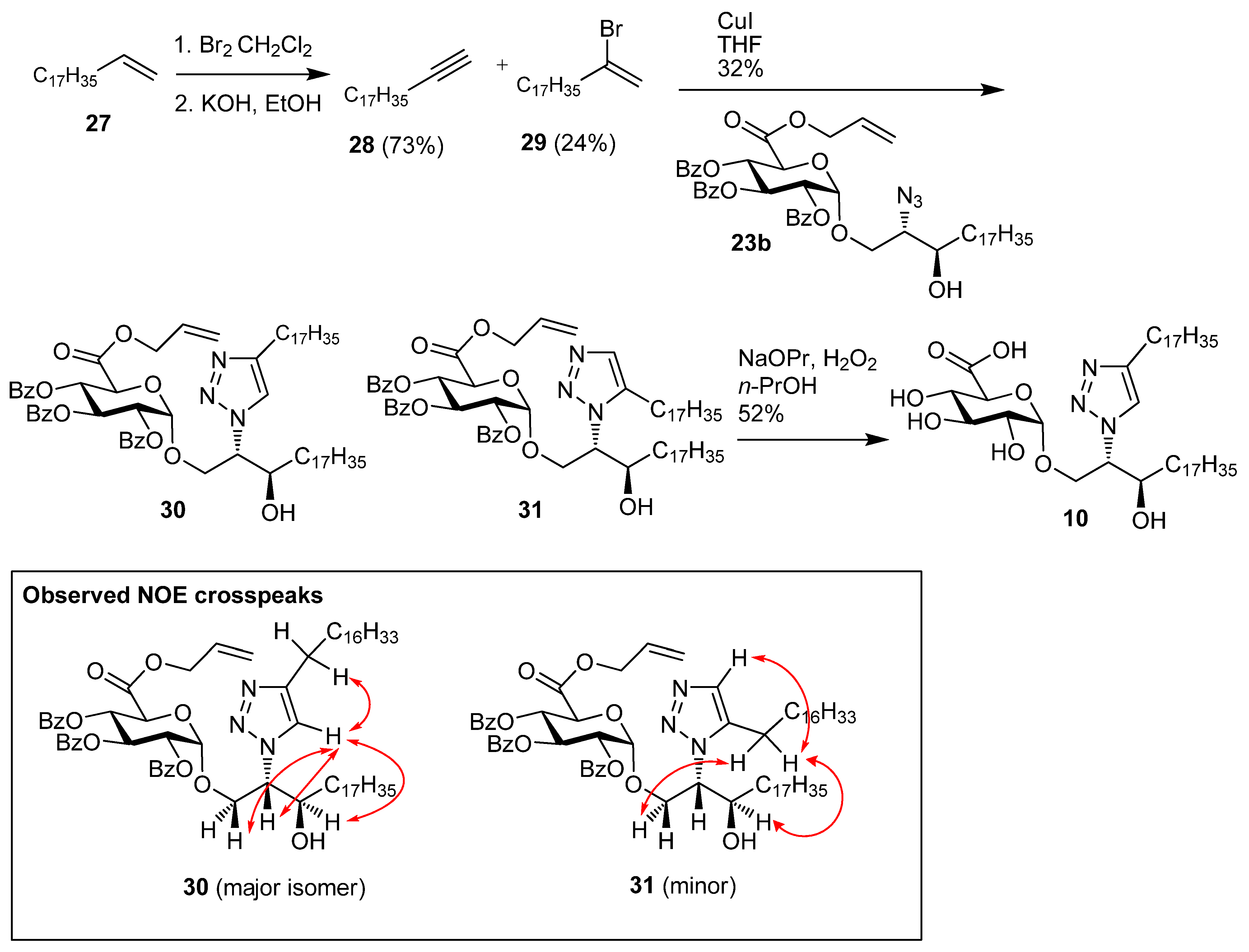

1-Nonadecyne (28). Nonadec-1-ene 27 (1.96 g, 7.37 mmol) was dissolved in CHCl3 (15 mL) and bromine (1.44 g, 9.00 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was then stirred for 30 min at room temp. The solution was diluted with cyclohexane, washed with Na2S2O4, water, brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give 1,2-dibromononadecane (3.1 g, 97%) as a white solid; Rf 0.51 (cyclohexane); IR (film) (cm−1): 2923, 2852, 1465, 1143; 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 4.17 (1H, m, CHBr), 3.85 (1H, dd, J = 10.2 Hz, J = 4.4 Hz, CHHBr), 3.63 (1H, t, J = 10.0 Hz, CHHBr), 2.14 (1H, m, CHHCHBr), 1.78 (1H, m, CHHCHBr), 1.56 (2H, m), 1.27 (28H, s, CH2), 0.88 (3H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, CH3); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ 53.2 (CHBr), 36.4 (CH2Br), 36.0, 31.9, 29.7 (2 s), 29.6, 29.5, 29.4 (2s), 28.8, 26.8, 22.7, 14.1 (CH3). 1,2-Dibromononadecane (2.00 g, 4.69 mmol) and KOH (2.67 g, 46.9 mmol) were dissolved in EtOH (40 mL) and heated at reflux for 48 h. The reaction mixture was then diluted with cyclohexane, washed with water, brine, dried over MgSO4, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. Flash chromatography (cyclohexane) gave 28 (0.91 g, 73%) as a white solid; Rf 0.51 (cyclohexane);IR (film) (cm−1): 3287, 2917, 2849, 1462, 908, 731, 630; 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 2.16 (2H, td, J = 7.1 Hz, J = 2.6 Hz, HCCCH2), 1.89 (1H, t, J = 2.6 Hz, CH), 1.52 (2H, m), 1,43 (30H, s), 0.88 (3H, t, J = 6.7, CH3); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ 84.5 (HCC), 68.0 (CCH), 32.0, 29.8, 29.7 (2s), 29.6, 29.5, 29.2, 28.8, 28.6, 27.0, 22.7, 18.4, 14.1 (CH3).

((2S,3R)-2-(4-Heptadecyl-1H-1,2,3-triazolyl)-3-hydroxyicosan-1-yl) 2,3,4-tri-O-benzoyl-α-d-galacto-pyranuronic acid, allyl ester (30) and ((2S,3R)-2-(5-heptadecyl-1H-1,2,3-triazolyl)-3-hydroxyicosan-1-yl) 2,3,4-tri-O-benzoyl-α-d-galactopyranuronic acid, allyl ester (31). Azide 23b (78 mg, 88.3 µmol) and alkyne 28 (46 mg, 177 µmol) were dried under vacuum. The reagents were taken up in toluene (1.5 mL), which was followed by the addition of copper(I) iodide (17 mg, 88 µmol), and the reaction mixture heated at reflux for 24 h. The reaction mixture was purified by flash chromatography to give (32 mg, 32%) as an inseparable 86:14 mixture of 30:31 (yellow solid); [α]D +32.0 (c 1.0, CHCl3); IR (film) cm−1: 3406, 3070, 2919, 2850, 1733, 1452, 1264, 1108, 1069, 709; 1H-NMR for major isomer (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ 7.93 (2H, dd, J = 8.4 Hz, J = 1.2 Hz, aromatic H), 7.91 (2H, dd, J = 8.4 Hz, J = 1.2 Hz, aromatic H), 7.88 (2H, dd, J = 8.4 Hz, J = 1.2 Hz, aromatic H), 7.52 (1H, m, aromatic H), 7.44 (2H, m, aromatic H), 7.37 (5H, m, aromatic H), 7.31 (2H, t, J = 7.8 Hz, aromatic H), 6.13 (1H, t, J = 9.8 Hz, H-3), 5.92 (1H, ddt, J = 17.0 Hz, J = 10.4 Hz, J = 6.1 Hz, CH=CH2) 5.67 (1H, t, J = 9.8 Hz, H-4), 5.41 (1H, d, J = 3.6 Hz, H-1), 5.30 (1H, dd, J = 9.8 Hz, J = 3.6 Hz, H-2), 5.18 (1H, dd, J = 17.1 Hz, J = 1.3 Hz, CH=CH2), 5.08 (1H, dd, J = 10.4 Hz, J = 0.9 Hz, CH=CH2), 4.56–4.64 (2H, overlapping signals), 4.48–4.54 (2H, overlapping signals), 4.30 (1H, dd, J = 11.1 Hz, J = 2.8 Hz, CHHO), 4.15 (1H, dd, J = 11.1 Hz, J = 6.8 Hz, CHHO), 4.05 (1H, br s, CHOH), 2.69 (1H, s, OH), 2.50 (1H, dt, J = 15.0 Hz, J = 7.9 Hz, CHH), 2.42 (1H, dt, J = 15.0 Hz, J = 7.8 Hz, CHH), 1.00–1.75 (64H, 32 x CH2), 0.88 (6H, t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 x CH3); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz): δ 167.0, 165.6, 165.3, 165.1 (each C=O), 148.4 (N=CH), 133.6, 133.4, 133.3, 130.7, 129.9, 129.8, 129.7, 128.9, 128.8, 128.6 (2s), 128.4 (2s), 128.3, 121.2, 119.6 (alkene CH2), 97.0 (C-1), 71.4 (CHN), 71.2 (C-2), 69.8 (C-4), 69.5 (C-5), 69.3 (C-3), 67.8 (CH2O), 66.9 (OCH2CH=CH2), 64.9 (CHOH), 33.8, 31.9, 29.7 (2s), 29.6 (2s), 29.5 (2s), 29.4 (2s), 29.3, 25.6, 25.5, 22.7 (each CH2), 14.1 (CH3); ES-HRMS calcd for C69H102O11N3 1148.7514, found m/z 1148.7570 [M+H]+.

((2S,3R)-2-(4-Heptadecyl-1H-1,2,3-triazolyl)-3-hydroxyicosan-1-yl) α-d-galactopyranuronic acid (10). The 86:14 mixture of protected glycolipids 30 and 31 (10 mg, 8.7 µmol) were dissolved in n-PrOH (2 mL) and H2O2 (30%, 0.2 mL), and to this nPrONa-nPrOH (500 µmL of 0.1 M, 50 µmol) was added at a rate of 80 µL/h. Water (5 mL) was then added to the reaction mixture and the solution centrifuged at 15000 rpm for 15 min, the supernatant was removed and the precipitate washed twice with water. The precipitate was then lyophilised to give a mixture of regioisomers (3.6 mg, 52%) where the 1,4-regioisomer 10 was the major product and there was also 12% of the 1,5-regioisomer. Analytical data for the major isomer 10: 1H-NMR (CDCl3-CD3OD 2:1, 600 MHz): δ 7.64 (1H, s, triazole H), 4.85 (1H, d, J = 2.9 Hz, H-1), 4.59 (1H, br s, CHN), 4.10-4.20 (2H, m, CH2O), 4.03 (1H, td, J = 7.8 Hz, J = 3,4 Hz, CHOH), 3.88 (4H, br s, OH), 3.63–3.73 (2H, m, H-3, H-5), 3.40–3.45 (2H, m, H-2, H-4), 2.69 (2H, t, J = 7.8 Hz, CH2), 1.62–1.72 (2H, overlapping signals, CH2), 1.1–1.55 (60H, overlapping signals, CH2), 0.89 (6H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2 x CH3); 13C-NMR (CDCl3-CD3OD 2:1, 150 MHz): δ 176.5 (C=O), 130.1, 128.6 (triazole C and CH), 100.1 (C-1), 73.9, 72.6, 72.0, 70.7, 70.3, 68.2, 66.2, 33.8, 32.2, 30.0, 29.7, 29.6, 25.8, 25.7, 22.9, 14.2; ES-HRMS calcd for C45H84O8N3 794.6258, found m/z 794.6276 [M-H]−.

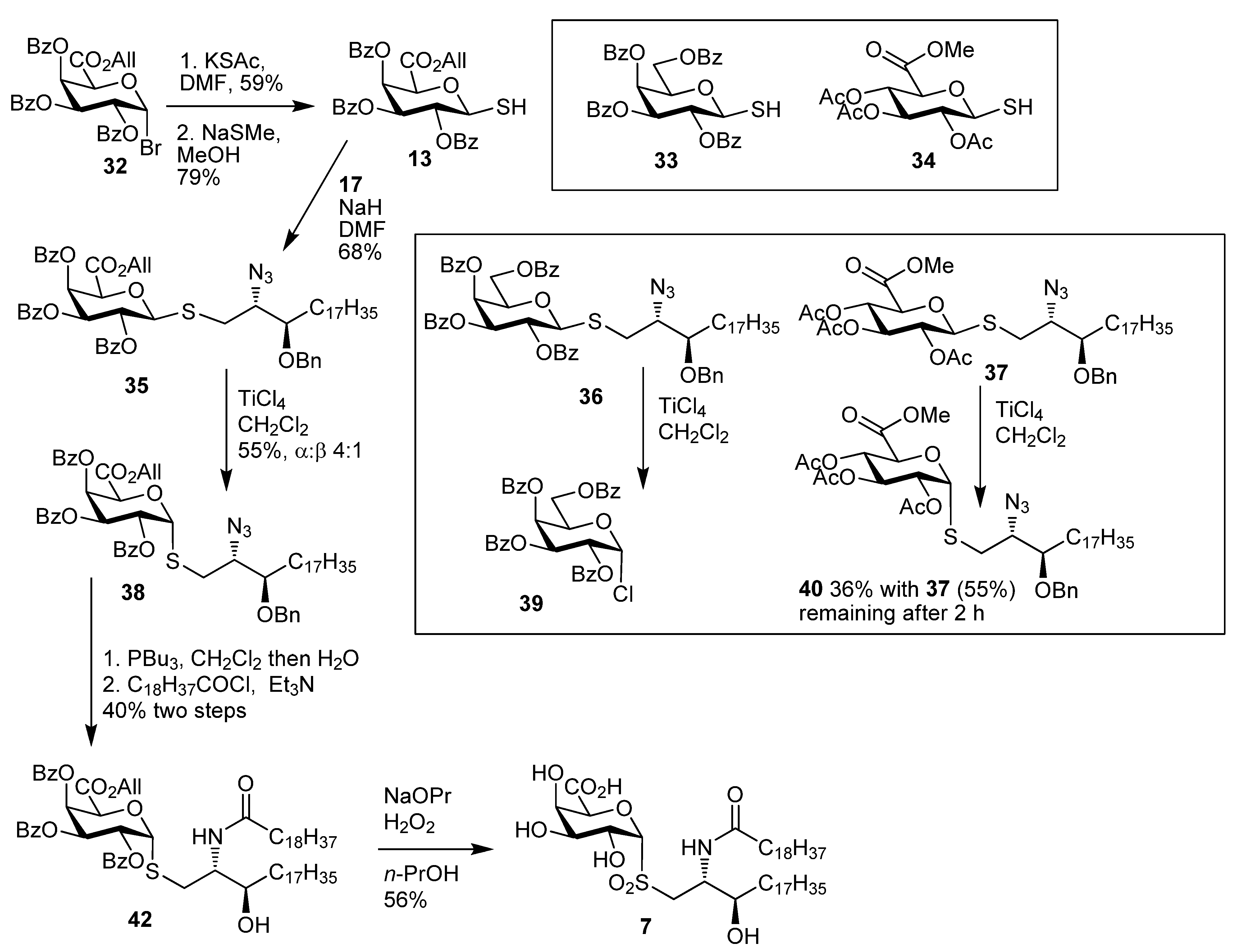

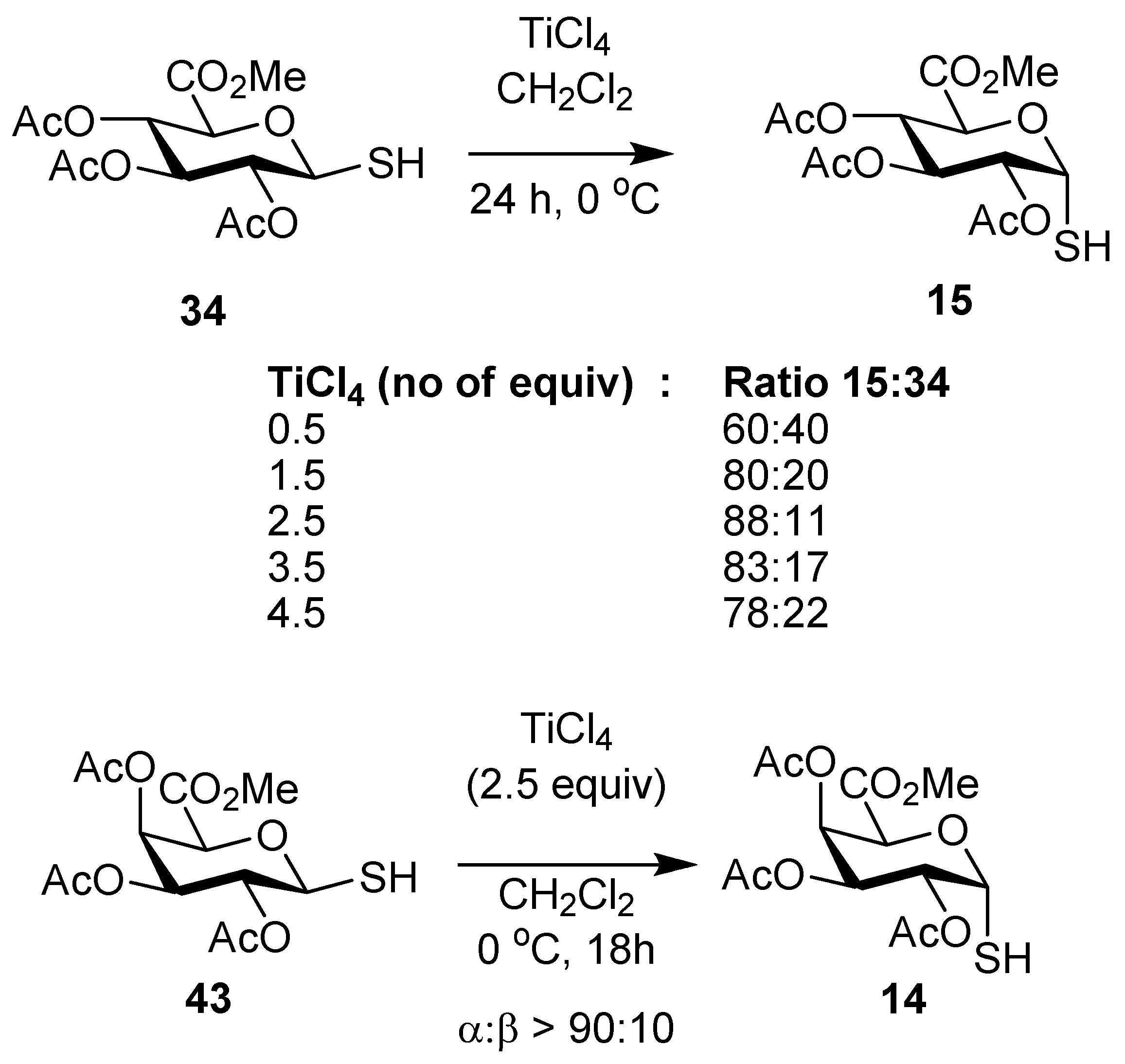

2,3,4-Tri-O-acetyl-α-thio-d-glucopyranosiduronic acid, methyl ester (15). To a stirred solution of the β-thiol10 34 (100 mg, 0.28 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (3 mL) was added TiCl4 (76 µL, 0.7 mmol) dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred for 10 min at room temp and then cooled to 0 °C overnight, and CH2Cl2 and satd NH4Cl were then added, and the phases were separated and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic layers were washed with water, brine, dried over MgSO4 and the solvent was removed to give an 8:1 mixture of 15 and 34 (65 mg, 65%) as a white foam. Analytical data for 15: IR (film) cm−1: 2955, 2572, 1747, 1438, 1370, 1214, 1077, 1042; 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ 5.98 (1H, t, J = 5.7, H-1), 5.39 (1H, t, J = 9.0, H-3), 5.17 (1H, t, J = 8.9, H-4), 5.02 (1H, dd, J = 9.3, 5.2, H-2), 4.76 (1H, d, J = 9.2, H-5), 3.76 (3H, s, OCH3), 2.09 (3H, s), 2.06 (3H, s), 2.05 (3H, s) (each OAc), 2.02 (1H, s, SH); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.5, 169.4, 167.7 (each C=O), 76.4 (C-1), 69.8 (C-2), 69.4 (C-5), 68.9 (C-4), 68.6 (C-3), 52.8 (OMe), 20.6, 20.5 (2s) (each OAc); ESI-HRMS calcd for C13H17O9S 349.0593, found m/z 349.0584 [M-H]−.

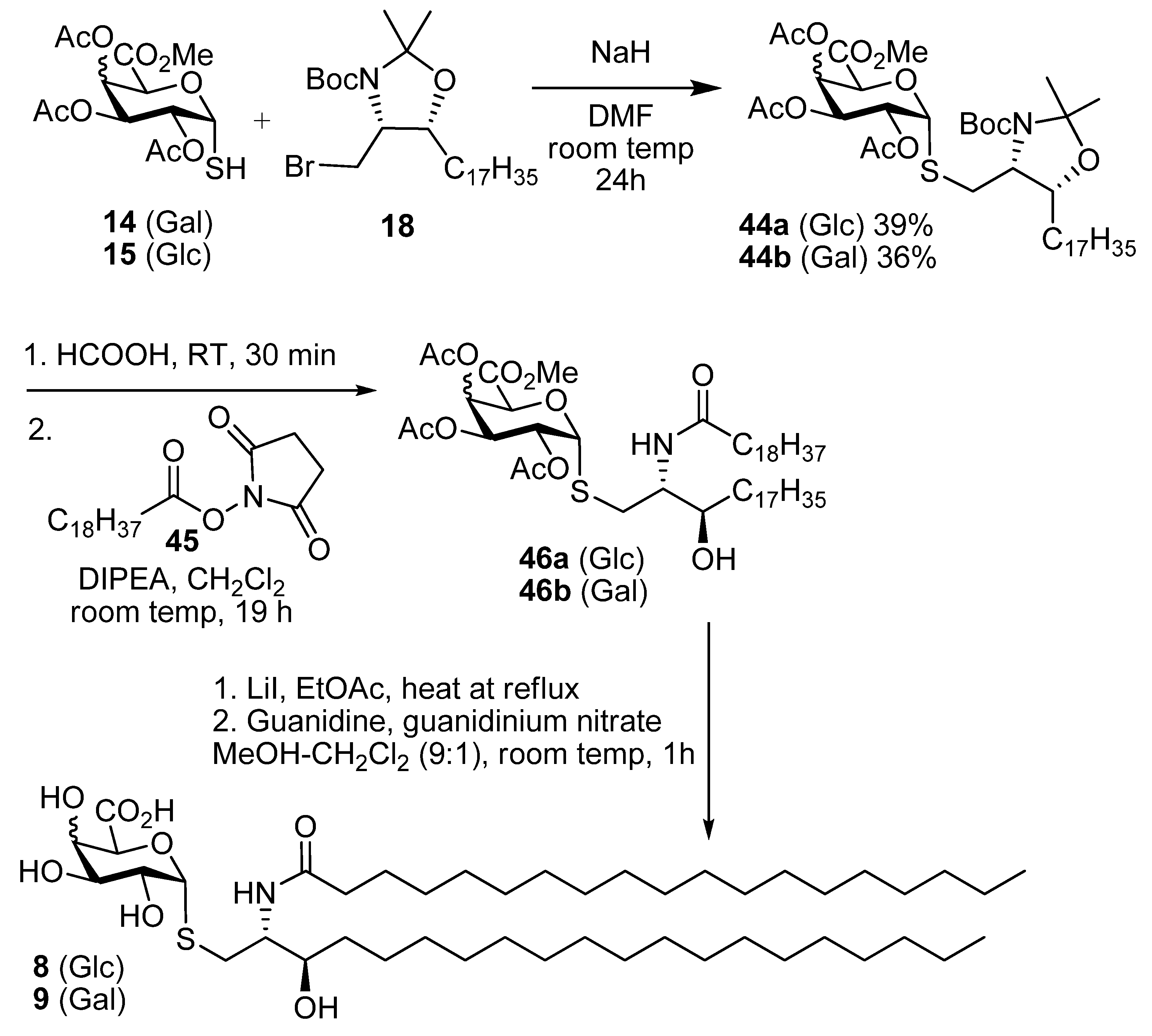

Methyl ((4S,5R)-5-heptadecyl-2,2-dimethyl-3-t-butoxycarbonyl-oxazolidin-4-yl)methyl 2,3,4-tri-O-acetyl-thio-α-d-glucopyranosiduronate (44a). Thiol 15 (155 mg, 0.44 mmol) was dissolved in dry DMF (3 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. Sodium hydride (16 mg of a 60% dispersion in mineral oil, 0.4 mmol) was added slowly and the reaction was stirred for 30 min. A solution of the bromide 18 (179 mg, 0.15 mmol) in DMF was then added dropwise and the mixture allowed to attain room temp and stirred overnight. EtOAc and water were added and the aqueous layer was washed with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were washed with water, brine, dried over MgSO4 and the solvent was removed. Flash chromatography (petroleum ether-EtOAc 4:1) gave 44a (42 mg, 39%) as a colourless oil; [α]D +60 (c, CHCl3); IR (film) cm−1: 2923, 2853, 1752, 1697, 1457, 1375, 1177, 1040; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.60–5.80 (1H, overlapping signals, H-1), 5.41–5.31 (1H, overlapping signals, H-3), 5.24–5.14 (1H, overlapping signals, H-4), 5.03 (1H, dd, J = 9.8, 5.5, H-2), 4.72 (1H, overlapping signals, H-5), 3.90–4.10 (2H, overlapping signals, CHO, CHN), 3.74 (3H, s, OMe), 2.08–2.00 (9H, overlapping signals, OAc), 1.05–1.80 (40H), 0.88 (3H, t, J = 6.7, CH3); 13C-NMR (125MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.8, 169.5, 169.4, 167.9 (C=O), 92.5, 83.3 (C-1), 80.1, 76.6 (C-3'), 70.0 (C-2), 69.5 (C-3), 69.1 (C-4), 68.9 (C-5), 58.6 (C-2'), 52.9 (OMe), 32.1, 29.9, 29.7, 29.5, 28.6 (each CH2), 22.8, 20.8, 20.7 (2s), 14.3 (each CH3); ESI-HRMS calcd for C41H71NO12SNa 824.4595, found m/z 824.4586 [M+Na]+.

Methyl ((2S,3R)-2-(N-nonadecanoylamino)-3-hydroxyicosan-1-yl) 2,3,4-tri-O-acetyl-thio-d-glucopyranosiduronate (46a). N-Hydroxysuccinimide (0.76 g, 6. 6 mmol) and EDC (1.25 g, 6.6 mmol) were added to a solution of nonadecanoic acid (1.87 g, 6.6 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (50 mL) and the mixture was stirred overnight at room temp. The solvent was concentrated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2. The solution was washed with water, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure to yield 45 as a white solid (2.45 g, 98%). This intermediate was used without further purification; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.83 (4H, s, O=CCH2CH2C=O), 2.60 (2H, t, J = 7.5, CH2C=O), 1.79–1.69 (2H, m, CH2), 1.39 (2H, dd, J = 14.9, 7.0, CH2), 1.27 (29H, s, each alkyl CH2), 0.88 (3H, t, J = 6.9, CH3); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.1, 168.6 (each C=O), 31.9, 30.9, 29.6, 29.6, 29.6, 29.5, 29.3, 29.0, 28.8, 25.6, 24.6, 22.7 (each CH2), 14.1 (CH3). Compound 44a (30 mg, 0.04 mmol) was taken up in formic acid (3 mL) and stirred vigorously for 30 min. Toluene (5 mL) was added and the solvents were removed under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was taken up in water and basified with solid NaHCO3. The mixture was then extracted into CH2Cl2, dried over MgSO4 and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was taken up in CH2Cl2 (2 mL) and DIPEA (22 µL, 0.13 mmol) was added. To this was added a solution of 45 (37 mg, 0.09 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1.5 mL) and the mixture was stirred at room temp for 16 h. The reaction mixture was partitioned between EtOAc and satd NaHCO3. Phases were separated and the aqueous phase extracted into EtOAc. The combined organic phases were washed with brine, dried over MgSO4 and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. Flash chromatography (petroleum ether-EtOAc 3:1) gave 46a (19 mg, 57% over two steps) as a white solid; [α]D +48 (c 1.0 in CHCl3); IR (film) cm−1: 3294 (br), 2917, 2850, 1751, 1650, 1467, 1219, 1043; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.12 (1H, d, J = 8.5, NH), 5.69 (1H, d, J = 5.2, H-1), 5.29 (1H, t, J = 9.0, H-3), 5.21 (1H, t, J = 9.0, H-4), 4.99 (1H, dd, J = 9.0, 5.2, H-2), 4.74 (1H, d, J = 9.0, H-5), 4.01 (1H, br s, CHO), 3.79–3.73 (3H, m, OMe), 3.68 (1H, br s, CHN), 3.03 (1H, dd, J = 14.0, 8.0, SCH2), 2.84 (1H, dd, J = 14.0, 3.5, SCH2), 2.19 (2H, d, J = 4.3, CH2), 2.08, 2.04, 2.03 (each 3H, each s, each CH3), 1.62 (4H, s, 2 × CH2), 1.45 (2H, m, CH2), 1.32–1.22 (60H, overlapping signals, each CH2), 0.87 (6H, t, J = 6.9, 2 × CH3); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.7, 169.8, 169.5, 169.4, 167.9 (each C=O), 83.5 (C-1), 73.6 (CHO), 70.0 (C-2), 69.2 (2s) (C-3 & C-5), 68.8 (C-4), 54.0 (CHN), 53.0 (OMe), 36.7, 34.0, 31.9 (each CH2), 29.7 (3s), 29.6, 29.4 (2s), 26.0, 25.7, 22.7 (each CH2), 20.7, 20.6 (2s), 14.1 (each CH3); ESI-HRMS calcd. for C52H94NO11S 940.6548, found m/z 940.6578 [M-H]−.

Methyl ((2S,3R)-2-(N-nonadecanoylamino)-3-hydroxyicosan-1-yl) 2,3,4-tri-O-acetyl-thio-d-glucopyranosiduronate (8). Protected lipid derivative 46a (3.0 mg, 0.3 µmol) was dissolved in anhydrous EtOAc (200 µL) and LiI (15 mg, 0.11 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was heated at 70 °C for 6 h. Upon cooling the reaction mixture was washed with H2O, brine, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was then taken up in a guanidine-guanidinium nitrate solution (2 mL, 1M in CH2Cl2-MeOH 1:9) the reaction was stirred at room temp for 1 h. The reaction was neutralised by the addition of Amberlite® resin IR-20, filtered and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified using lipophilic Sephadex® LH-20 to give the title compound (1.4 mg) as a white powder; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3-MeOD 2:1) δ 5.21 (1H, d, J = 4.5), 4.31 (1H, br s), 3.78 (1H, br s), 3.58 (2H, br s), 3.45 (1H, s), 3.31–3.50 (2H, overlapping signals), 2.55–2.80 (2H, m, SCH2), 0.85-2.15 (66H), 0.65 (6H, br s, 2 CH3); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3-MeOD 2:1) δ 175.5 (C=O), 87.6 (C-1), 73.5 (CHOH), 71.4 (C-2), 70.4 (C-3), 69.0 (C-5), 67.2 (C-4), 53.6 (CHN), 35.3, 31.3 (CH2S), 34.0, 29.4, 26.1, 26.0, 22.9, 22.7, 19.3 (each CH2), 14.1 (CH3); ESI-HRMS calcd for C45H86NO8S 800.6074, found m/z 800.6077 [M-H]−.