Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Theoretical Studies of New Quasi-Podands from Bile Acid Derivatives Linked by 1,2,3-Triazole Rings

Abstract

:1. Introduction

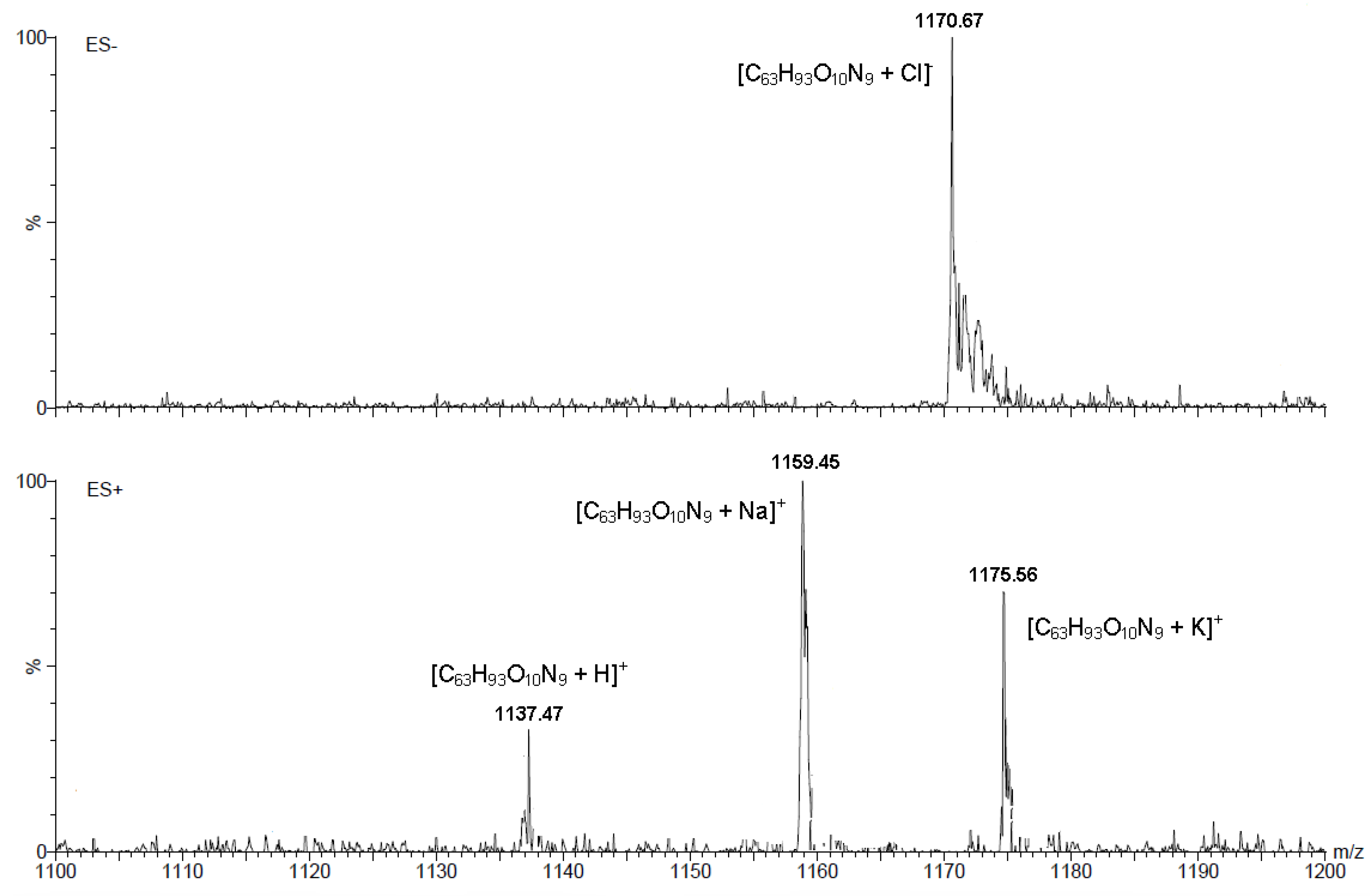

2. Results and Discussion

| Focal Predicted Activity (PA > 0.70) | Compound | |

|---|---|---|

| 9 | 10 | |

| Acylcarnitine hydrolase inhibitor | 0.79 | 0.90 |

| Glyceryl-ether monooxygenase inhibitor | 0.72 | 0.84 |

| Alkenylglycerophosphocholine hydrolase inhibitor | 0.82 | 0.82 |

| Biliary tract disorders treatment | 0.73 | 0.81 |

| Hypolipemic | – | 0.77 |

| Alkylacetylglycerophosphatase inhibitor | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| Cholesterol antagonist | 0.79 | 0.72 |

| Compound | Heat of Formation [kcal/mol] | Distance [Å] of N(28)-N(28') | Bond Angle [°] of N(28)-C(31)-C(32) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | −217.30 | 5.49 | 110.8 |

| 10 | −382.73 | 5.49 | 110.8 |

| 11 | −440.71 | 5.75 | 110.8 |

| 12 | −568.23 | 5.73 | 111.7 |

| 13 | −694.62 | 5.46 | 110.8 |

3. Experimental

3.1. General

Synthesis: General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compounds 9 and 11

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nicolaou, K.C.; Montagnon, T. Steroids and the Pill. In Molecules that Changed the World; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2008; pp. 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Dewick, P.M. Steroids. In Medicinal Natural Products A Biosynthetic Approach, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2009; pp. 275–277. [Google Scholar]

- Lack, L.; Donity, F.O.; Walker, T.; Singletary, G.D. Synthesis of conjugated bile acids by means of a peptide coupling reagent. J. Lipid Res. 1973, 14, 367–370. [Google Scholar]

- Tserng, K.-Y.; Hachey, D.L.; Klein, P.D. An improved procedure for the synthesis of glycine and taurine conjugates of bile acids. J. Lipid Res. 1977, 18, 404–407. [Google Scholar]

- Batta, A.K.; Salen, G.; Shefer, S. Substrate specificity of cholylglycine hydrolase for the hydrolysis of bile acid conjugates. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 15035–15039. [Google Scholar]

- Huijghebaert, S.M.; Hofmann, A.F. Influence of the amino acid moiety on deconjugation of bile acid amidates by cholylglycine hydrolase or human fecal cultures. J. Lipid Res. 1986, 27, 742–752. [Google Scholar]

- Yuexian, L.; Dias, J.R. Dimeric and oligomeric steroids. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 283–304. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A.P. Cholaphanes, et al; steroids as structural components in molecular engineering. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1993, 22, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willimann, P.; Marti, T.; Fürer, A.; Diederich, F. Steroids in molecular recognition. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 1567–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamminen, J.; Kolehmainen, E. Bile acids as building blocks of supramolecular hosts. Molecules 2001, 6, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, U.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Sarkar, A.; Rao, P.; Indi, S.S. Hydrophobic pockets in a nonpolymeric aqueous gel: Observation of such a gelation process by color change. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2281–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, X.X. Invertible amphiphilic molecular pockets made of cholic acid. Langmuir 2009, 25, 10913–10917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, J.; Zhu, X.X.; Junk, M.J.N.; Hinderberger, D. Molecular pockets derived from cholic acid as chemosensors for metal ions. Langmuir 2010, 26, 2958–2962. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Junk, M.J.N.; Luo, J.; Hinderberger, D.; Zhu, X.X. 1,2,3-Triazole-containing molecular pockets derived from cholic acid: The influence of structure on host−guest coordination properties. Langmuir 2010, 26, 13415–13421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janout, V; Jing, B.W.; Regen, S.L. Molecular umbrella-assisted transport of an oligonucleotide across cholesterol-rich phospholipid bilayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15862–15870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janout, V; Jing, B.W.; Regen, S.L. Bioconjugate-based molecular umbrellas. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009, 20, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospieszny, T.; Koenig, H.; Brycki, B. Synthesis and spectroscopic studies of new quasi podands from bile acid derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 4700–4704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Dias, J.R. Synthesis and characterization of dimeric bile acid ester derivatives. J. Prakt. Chem. 1997, 339, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Dias, J.R. Synthesis of α- and β-dimers of lithocholic acid esters. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 1996, 28, 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.P.; Muller, J.G.; Burrows, C.J. Structural effects in novel steroidal polyamine-DNA binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 12077–12078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.P.; Cullimore, P.A.; McDonald, R.S.; O’Leary, S. Large hydrophobic interactions with clearly defined geometry. A dimeric steroid with catalytic properties. Can. J. Chem. 1982, 60, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paryzek, Z.; Joachimiak, R.; Piasecka, M.; Pospieszny, T. A new approach to steroid dimers and macrocycles by the reaction of 3-chlorocarbonyl derivatives of bile acids with O,O-, N,N-, and S,S-dinucleophile. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 46, 6212–6215. [Google Scholar]

- Willemen, H.M.; Vermonden, T.; Marcelis, A.T.M.; Sudhölter, E.J.R. N-Cholyl amino acid alkyl esters−a novel class of organogelators. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 12, 2329–2335. [Google Scholar]

- Willemen, H.M.; Vermonden, T.; Marcelis, A.T.M.; Sudhölter, E.J.R. Alkyl derivatives of cholic acid as organogelators: One-component and two-component gels. Langmuir 2002, 18, 7102–7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkonen, A.; Lahtinen, M.; Virtanen, E.; Kaikkonen, S.; Kolehmainen, E. Bile acid amidoalcohols: Simple organogelators. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2004, 20, 1233–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steed, J.W.; Atwood, J.L. Supramolecular Chemistry, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: London, UK, 2009; pp. 118–120, 278–281. [Google Scholar]

- Maia, A.; Landini, D.; Leska, B.; Schroeder, G. Silicon polypodands: Powerful metal cation complexing agents and solid–liquid phase-transfer catalysts of new generation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 4149–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H.C.; Finn, M.G.; Sharpless, K.B. Click chemistry: Diverse chemical function from a few good reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, S.; Muldoon, J.; Finn, M.G.; Fokin, V.V.; Kolb, H.C.; Sharpless, K.B. “On water”: Unique reactivity of organic compounds in aqueous suspension. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 3275–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornøe, Ch. W.; Christensen, C.; Meldal, M. Peptidotriazoles on solid phase: [1,2,3]-Triazoles by regiospecific copper(I)-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions of terminal alkynes to azides. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 3057–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Xue, P.; Sun, H.H.Y.; Williams, I.D.; Sharpless, K.B.; Fokin, V.V.; Jia, G. Ruthenium-catalyzed cycloaddition of alkynes and organic azides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15998–15999. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, H.C.; Finn, M.G.; Sharpless, K.B. Click-Chemie: Diverse chemische funktionalität mit einer handvoll guter reaktionen. Angew. Chem. 2001, 113, 2056–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tron, G.C.; Pirali, T.; Billington, R.A.; Canonico, P.L.; Sorba, G.; Genazzani, A.A. Click chemistry reactions in medicinal chemistry: Applications of the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition between azides and alkynes. Med. Res. Rev. 2008, 28, 278–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latyshev, G.V.; Baranov, M.S.; Kazantsev, A.V.; Averin, A.D.; Lukashev, N.V.; Beletskaya, I.P. Copper-catalyzed [1,3]-dipolar cycloaddition for the synthesis of macrocycles containing acyclic, aromatic and steroidal moieties. Synthesis 2009, 2605–2615. [Google Scholar]

- Pore, V.S.; Aher, N.G.; Kumar, M.; Shukla, P.K. Design and synthesis of fluconazole/bile acid conjugate using click reaction. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 11178–11186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Pandey, P.S. Anion Recognition by 1,2,3-triazolium receptors: Application of click chemistry in anion recognition. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Chhatra, R.K.; Pandey, P.S. Synthesis of click bile acid polymers and their application in stabilization of silver nanoparticles showing iodide sensing property. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatmurge, N.S.; Hazra, B.G.; Pore, V.S.; Shirazi, F.; Deshpande, M.V.; Kadreppa, S.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Gonnade, R.G. Synthesis and biological evaluation ofbile aciddimers linked with 1,2,3-triazoleandbis-β-lactam. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 3823–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospieszny, T.; Małecka, I.; Paryzek, Z. Synthesis and spectroscopic studies of new bile acid derivatives linked by a 1,2,3-triazole ring. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, T.M.; McMurry, T.J.; Hosseini, M.W.; Reyes, Z.E.; Hahn, F.E.; Raymond, K.N. Ferric ion sequestering agents. 22. Synthesis and characterization of macrobicyclic iron(III) sequestering agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 2965–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aher, N.G.; Pore, V.S.; Patil, S.P. Design, synthesis, and micellar properties of bile acid dimers and oligomers linked with a 1,2,3-triazole ring. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 12927–12934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maue, M.; Bernitzki, K.; Eilermann, M.; Schrader, T. Bifunctional bisamphiphilic transmembrane building blocks for artificial – signal transduction. Synthesis 2008, 14, 2247–2256. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-López, P.; de la Torre, M.C.; Montenegro, H.E.; Asenjo, M.; Sierra, M.A. A straightforward synthesis of tetrameric estrone-based macrocycles. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 3555–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-López, P.; de la Torre, M.C.; Asenjo, M.; Ramírez-Castellanos, J.; González-Calbet, J.M.; Rodrígez-Gimeno, A.; Ramírez de Arellano, C.; Sierra, M.A. A new family of “clicked” estradiol-based low-molecular-weight gelatores having highly symmetry-dependent gelation ability. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 10281–10283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharma Expert Predictive Services Version 2.0 © 2011–2013. Available online: http://www.pharmaexpert.ru/PASSOnline/ (accessed on 1 November 2013).

- Poroikov, V.V.; Filimonov, D.A.; Borodina, Y.V.; Lagunin, A.A.; Kos, A. Robustness of biological activity spectra predicting by computer program PASS for noncongeneric sets of chemical compounds. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2000, 40, 1349–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poroikov, V.V.; Filimonov, D.A. How to acquire new biological activities in old compounds by computer prediction. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2002, 16, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poroikov, V.V.; Filimonov, D.A. Predictive Toxicology; Helma, C., Ed.; Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 459–478. [Google Scholar]

- Stepanchikova, A.V.; Lagunin, A.A.; Filimonov, D.A.; Poroikov, V.V. Prediction of biological activity spectra for substances: Evaluation on the diverse sets of drug-like structures. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujistsu. CAChe 5.04 UserGuide, Fujitsu: Chiba, Japan, 2003.

- Stewart, J.J.P. Optimization of parameters for semiempirical methods. III Extension of PM3 to Be, Mg, Zn, Ga, Ge, As, Se, Cd, In, Sn, Sb, Te, Hg, Tl, Pb, and Bi. J. Comput. Chem. 1991, 12, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.J.P. Optimization of parameters for semiempirical methods I. Method. J. Comput. Chem. 1989, 10, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds 9–13 are available from the authors.

© 2014 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Pospieszny, T.; Koenig, H.; Kowalczyk, I.; Brycki, B. Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Theoretical Studies of New Quasi-Podands from Bile Acid Derivatives Linked by 1,2,3-Triazole Rings. Molecules 2014, 19, 2557-2570. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19022557

Pospieszny T, Koenig H, Kowalczyk I, Brycki B. Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Theoretical Studies of New Quasi-Podands from Bile Acid Derivatives Linked by 1,2,3-Triazole Rings. Molecules. 2014; 19(2):2557-2570. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19022557

Chicago/Turabian StylePospieszny, Tomasz, Hanna Koenig, Iwona Kowalczyk, and Bogumił Brycki. 2014. "Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Theoretical Studies of New Quasi-Podands from Bile Acid Derivatives Linked by 1,2,3-Triazole Rings" Molecules 19, no. 2: 2557-2570. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19022557