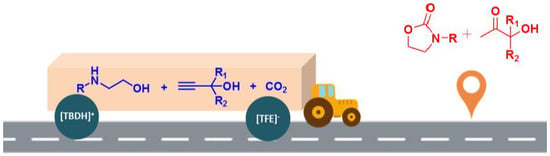

Ionic Liquid-Promoted Three-Component Domino Reaction of Propargyl Alcohols, Carbon Dioxide and 2-Aminoethanols: A Thermodynamically Favorable Synthesis of 2-Oxazolidinones

Abstract

:1. Introduction

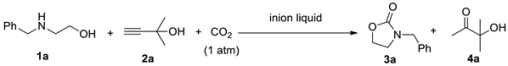

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Optimization of the Reaction Conditions

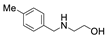

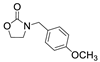

2.2. Investigation of Substrate Applicability

2.3. Recycle Tests

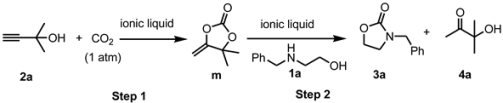

2.4. Mechanism Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and General Analytic Methods

3.2. General Procedure for the Synthesis of 2-Aminoethanol Derivatives [33]

3.3. General Procedure for the Synthesis of ILs [67]

3.4. General Procedure for the Synthesis of 2-Oxazolidinones and α-Hydroxyl Ketones

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Choi, S.; Drese, J.H.; Jones, C.W. Adsorbent materials for carbon dioxide capture from large anthropogenic point sources. ChemSusChem 2009, 2, 796–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alessandro, D.M.; Smit, B.; Long, J.R. Carbon dioxide capture: Prospects for new materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6058–6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Quéré, C.; Raupach, M.R.; Canadell, J.G.; Marland, G. Trends in the sources and sinks of carbon dioxide. Nat. Geosci. 2009, 2, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cokoja, M.; Bruckmeier, C.; Rieger, B.; Herrmann, W.A.; Kühn, F.E. Transformation of carbon dioxide with homogeneous transition-metal catalysts: A molecular solution to a global challenge? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 8510–8537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, M.; Jørgensen, M.; Krebs, F.C. The teraton challenge. A review of fixation and transformation of carbon dioxide. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 43–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börjesson, M.; Moragas, T.; Gallego, D.; Martin, R. Metal-catalyzed carboxylation of organic (pseudo)halides with CO2. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 6739–6749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.; Teong, S.P.; Zhang, Y. Transition metal complex catalyzed carboxylation reactions with CO2. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 293, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Diao, Z.-F.; Guo, C.X.; He, L.N. Carboxylation of olefins/alkynes with CO2 to industrially relevant acrylic acid derivatives. J. CO2 Util. 2013, 1, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, R.R.; Pornpraprom, S.; D’Elia, V. Catalytic strategies for the cycloaddition of pure, diluted, and waste CO2 to epoxides under ambient conditions. ACS Catal. 2017, 8, 419–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, M.; Pasquale, R.; Young, C. Synthesis of cyclic carbonates from epoxides and CO2. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 1514–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.F.; Yuan, G.Q.; Chen, H.J.; Jiang, H.F.; Li, Y.W.; Qi, C.R. Efficient conversion of CO2 with olefins into cyclic carbonates via a synergistic action of I2 and base electrochemically generated in situ. Electrochem. Commun. 2013, 34, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Isahak, W.N.R.; Che Ramli, Z.A.; Mohamed Hisham, M.W.; AmbarYarmo, M. The formation of a series of carbonates from carbon dioxide: Capturing and utilisation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshbaf, S.; Fekri, L.Z.; Nikpassand, M.; Mohammadi, R.; Vessally, E. Dehydrative condensation of β-aminoalcohols with CO2: An environmentally benign access to 2-oxazolidinone derivatives. J. CO2 Util. 2018, 25, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulla, S.; Felton, C.M.; Ramidi, P.; Gartia, Y.; Ali, N.; Nasini, U.B.; Ghosh, A. Advancements in oxazolidinone synthesis utilizing carbon dioxide as a C1 source. J. CO2 Util. 2013, 2, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; He, L.N. Upgrading carbon dioxide by incorporation into heterocycles. ChemSusChem 2015, 8, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.-Z.; He, L.N.; Gao, J.; Liu, A.H.; Yu, B. Carbon dioxide utilization with C–N bond formation: Carbon dioxide capture and subsequent conversion. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 6602–6639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vessally, E.; Mohammadi, R.; Hosseinian, A.; Edjlali, L.; Babazadeh, M. Three components coupling of amines, alkyl halides and carbon dioxide: An environmentally benign access to carbamate esters (urethanes). J. CO2 Util. 2018, 24, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshadi, S.; Vessally, E.; Hosseinian, A.; Soleimani-amiric, S.; Edjlali, L. Three-component coupling of CO2, propargyl alcohols, and amines: An environmentally benign access to cyclic and acyclic carbamates (A Review). J. CO2 Util. 2017, 21, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.H.; Himeda, Y.; Muckerman, J.T.; Manbeck, G.F.; Fujita, E. CO2 hydrogenation to formate and methanol as an alternative to photo- and electrochemical CO2 reduction. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12936–12973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunasekar, G.H.; Park, K.; Jung, K.D.; Yoon, S. Recent developments in the catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 to formic acid/formate using heterogeneous catalysts. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, A.; Bansode, A.; Urakawa, A.; Bavykina, A.V.; Wezendonk, T.A.; Makkee, M.; Gascon, J.; Kapteijn, F. Challenges in the greener production of formates/formic acid, methanol, and DME by heterogeneously catalyzed CO2 hydrogenation processes. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 9804–9838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.L.; Jiang, Z.; Su, D.S.; Wang, J.Q. Research progress on the indirect hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to methanol. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Yang, G.H.; Tao, K.; Yoneyama, Y.; Tan, Y.S.; Tsubaki, N. An introduction of CO2 conversion by dry reforming with methane and new route of low-temperature methanol synthesis. Accounts Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1838–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khusnutdinova, J.R.; Garg, J.A.; Milstein, D. Combining low-pressure CO2 capture and hydrogenation to form methanol. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 2416–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, J.; Pérez-Balado, C.; Iglesias, B.; Muñoz, L. Carbon dioxide as a carbonylating agent in the synthesis of 2-oxazolidinones, 2-oxazinones, and cyclic ureas: Scope and limitations. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 3037–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.J.; Khan, Y.; Maeng, J.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Hwang, J.; Cheong, M.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, H.S. Efficient catalytic systems for the carboxylation of diamines to cyclic ureas using ethylene urea as a promoter. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 209, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Moreno, R.B. Synthesis of ureas from titanium imido complexes using CO2 as a C1 reagent at ambient temperature and pressure. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 1334–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.H.; Gu, L.; Gao, Y.G.; Qin, Y.S.; Wang, X.H.; Wang, F.S. Biodegradable CO2-based polycarbonates with rapid and reversible thermal response at body temperature. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2013, 51, 1893–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Sablong, R.J.; Koning, C.E. Chemoselective alternating copolymerization of limonene dioxide and carbon dioxide: A new highly functional aliphatic epoxy polycarbonate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11572–11576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geschwind, J.; Wurm, F.; Frey, H. From CO2-based multifunctional polycarbonates with a controlled number of functional groups to graft polymers. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2013, 214, 892–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heravi, M.M.; Zadsirjan, V. Oxazolidinones as chiral auxiliaries in asymmetric aldol reactions applied to total synthesis. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2013, 24, 1149–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heravi, M.M.; Zadsirjan, V.; Farajpour, B. Applications of oxazolidinones as chiral auxiliaries in the asymmetric alkylation reaction applied to total synthesis. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 30498–30551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallesham, B.; Rajesh, B.M.; Reddy, P.R.; Srinivas, D.; Trehan, S. Highly efficient CuI-catalyzed coupling of aryl bromides with oxazolidinones using Buchwald’s protocol: A short route to linezolid and toloxatone. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 963–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surmaitis, R.M.; Nappe, T.M.; Cook, M.D. Serotonin syndrome associated with therapeutic metaxalone in a patient with cirrhosis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 34, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quayle, W.C.; Oliver, D.P.; Zrna, S. Field dissipation and environmental hazard assessment of clomazone, molinate, and thiobencarb in Australian rice culture. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 7213–7220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buyck, T.; Pasche, D.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, J. Synthesis of oxazolidin-2-ones by oxidative coupling of isonitriles, phenyl vinyl selenone and water. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 2278–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdach, A.; Hadrami, E.M.E.; Gil, S.; Zaragozá, R.J.; Zaballos-Garcíaa, E.; Sepúlveda-Arquesa, J. Reactivity difference between diphosgene and phosgene in reaction with (2,3-anti)-3-amino-1,2-diols. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 6392–6397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, R.; Raut, D.S.; Della Ca’, N.; Fini, F.; Carfagna, C.; Gabriele, B. Catalytic oxidative carbonylation of amino moieties to ureas, oxamides, 2-oxazolidinones, and benzoxazolones. ChemSusChem 2015, 8, 2204–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, C.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Cao, C.; Pang, G.; Shi, Y. Synthesis of oxazolidinones and derivatives through three-component fixation of carbon dioxide. Chem. Cat. Chem. 2018, 10, 3057–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, Y.; Foo, S.W.; Yamazaki, Y.; Saito, S. Catalytic fluoride triggers dehydrative oxazolidinone synthesis from CO2. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 50851–50857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, F.; Okada, Y.; Matsumoto, C.; Yamada, M.; Nakazawa, K.; Mukai, C. Energyless CO2 absorption, generation, and fixation using atmospheric CO2. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 64, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.H.; Lee, K.B.; Hyun, J.C.; Kim, S.H. Correlation and prediction of the solubility of carbon dioxide in aqueous alkanolamine and mixed alkanolamine solutions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2002, 41, 1658–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, S.W.; Takada, Y.; Yamazaki, Y.; Saito, S. Dehydrative synthesis of chiral oxazolidinones catalyzed by alkali metal carbonates under low pressure of CO2. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 4717–4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, S.I.; Kanamaru, H.; Senboku, H.; Arai, M. Preparation of cyclic urethanes from amino alcohols and carbon dioxide using ionic liquid catalysts with alkali metal promoters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2006, 7, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, H.; Baba, A.; Nomura, R.; Kori, M.; Ogawa, S. Improvement of the process in the synthesis of 2-oxazoiidinones from 2-amino alcohols and carbon dioxide by use of triphenylstibine oxide as catalyst. Ind. Eng. Chem. Prod. Res. Dev. 1985, 24, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanage, B.M.; Fujita, S.I.; Ikushimabc, Y.; Arai, M. Synthesis of cyclic ureas and urethanes from alkylen e diamines and amino alcohols with pressurized carbon dioxide in the absence of catalysts. Green Chem. 2003, 5, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez, R.; Concepción, P.; Corma, A.; García, H. Ceria nanoparticles as heterogeneous catalyst for CO2 fixation by omega-aminoalcohols. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 4181–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulla, S.; Felton, C.M.; Gartia, Y.; Ramidi, P.; Ghosh, A. Synthesis of 2-oxazolidinones by direct condensation of 2-aminoalcohols with carbon dioxide using chlorostannoxanes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2013, 1, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, T.; Fernández, I.; Steadman, B.; Mannisto, J.K.; Repo, T. Carbon dioxide-based facile synthesis of cyclic carbamates from amino alcohols. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 3166–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paz, J.; Pérez-Balado, C.; Iglesias, B.; Muñoz, L. Carbonylation with CO2 and phosphorus electrophiles: A convenient method for the synthesis of 2-oxazolidinones from 1,2-amino alcohols. Synlett 2009, 3, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinsmore, C.J.; Mercer, S.P. Carboxylation and Mitsunobu reaction of amines to give carbamates: Retention vs inversion of configuration is substituent-dependent. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2885–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, M.; Honda, M.; Nakagawa, Y.; Tomishige, K. Direct conversion of CO2 with diols, aminoalcohols and diamines to cyclic carbonates, cyclic carbamates and cyclic ureas using heterogeneous catalysts. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2014, 89, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.D.; Cao, Y.; Ma, R.; He, L.N. Thermodynamically favorable protocol for the synthesis of 2-oxazolidinones via Cu(I)-catalyzed three-component reaction of propargylic alcohols, CO2 and 2-aminoethanols. J. CO2 Util. 2018, 25, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.W.; Zhou, Z.H.; Wang, M.Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, P.; Xun, J.Y.; He, L.N. Thermodynamically favorable synthesis of 2-oxazolidinones through silver-catalyzed reaction of propargylic alcohols, CO2, and 2-aminoethanols. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 2054–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.D.; Song, Q.W.; Lang, X.D.; Chang, Y.; He, L.N. Ag(I) /TMG-promoted cascade reaction of propargyl alcohols, carbon dioxide, and 2-aminoethanols to 2-oxazolidinones. Chemphyschem 2017, 18, 3182–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvim, H.G.O.; Correa, J.R.; Assumpção, J.A.F.; da Silva, W.A.; Rodrigues, M.O.; de Macedo, J.L.; Fioramonte, M.; Gozzo, F.C.; Gatto, C.C.; Neto, B.A.D. Heteropolyacid-containing ionic liquid-catalyzed multicomponent synthesis of bridgehead nitrogen heterocycles: Mechanisms and mitochondrial staining. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 4044–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.Y.; Song, Q.W.; Ma, R.; Xie, J.N.; He, L.N. Efficient conversion of carbon dioxide at atmospheric pressure to 2-oxazolidinones promoted by bifunctional Cu(II)-substituted polyoxometalate-based ionic liquids. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.K.; Baker, G.A.; Zhao, H. Ether- and alcohol-functionalized task-specific ionic liquids: Attractive properties and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 4030–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giernoth, R. Task-specific ionic liquids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 2834–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yu, B.; Zhang, H.; Xu, H.; Hao, L.; Han, B.; Liu, Z. Task-specific ionic liquid and CO2-cocatalysed efficient hydration of propargylic alcohols to α-hydroxy ketones. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 2297–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Yu, B.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hao, L.; Gao, X.; Liu, Z. A protic ionic liquid catalyzes CO2 conversion at atmospheric pressure and room temperature: Synthesis of quinazoline-2,4-(1H,3H)-diones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5922–5925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Cà, N.; Gabriele, B.; Ruffolo, G.; Veltri, L.; Zanetta, T.; Costa, M. Effective guanidine-catalyzed synthesis of carbonate and carbamate derivatives from propargyl alcohols in supercritical carbon dioxide. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.W.; Yu, B.; Li, X.D.; Ma, R.; Diao, Z.F.; Li, R.G.; Li, W.; He, L.N. Efficient chemical fixation of CO2 promoted by a bifunctional Ag2WO4/Ph3P system. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 1633–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.D.; Ma, R.; He, L.N. Fe(NO3)3·9H2O-catalyzed aerobic oxidation of sulfides to sulfoxides under mild conditions with the aid of trifluoroethanol. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2015, 26, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuklov, I.A.; Dubrovina, N.V.; Börner, A. Fluorinated alcohols as solvents, cosolvents and additives in homogeneous catalysis. Synthesis 2007, 19, 2925–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, K.S.; Kesavan, V.; Crousse, B.; Bonnet-Delpon, D.; Bégué, J.P. Mild and selective oxidation of sulfur compounds in trifluoroethanol: Diphenyl disulfide and methyl phenyl sulfoxide. Org. Synth. 2003, 80, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, A.G.; Liu, L.; Wu, G.F.; Chen, G.; Chen, X.Z.; Ye, W.D. Aza-Michael addition of aliphatic or aromatic amines to α,β-unsaturated compounds catalyzed by a DBU-derived ionic liquid under solvent-free conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 1653–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors. |

| Entry | IL (mol%) | Yield/% [b] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 4a | ||

| 1 | [DBUH][Im] | 14 | 13 |

| 2 | [DBUH][OAc] | 19 | 21 |

| 3 | [DBUH][TFE] | 23 | 27 |

| 4 | [DBUH][TFA] | 21 | 21 |

| 5 | [DBUH][Cl] | 13 | 9 |

| 6 | [TBDH][Im] | 27 | 30 |

| 7 | [TMGH][Im] | 22 | 21 |

| 8 | [P4444][Im] | trace | trace |

| 9 | [TBDH][TFE] | 33 | 39 |

| Entry | IL (mol%) | Yield/% [b] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 4a | ||

| 1 | [DBUH][Im] (10) | 13 | 11 |

| 2 | [DBUH][OAc] (10) | 7 | 6 |

| 3 | [DBUH][TFE] (10) | 3 | 5 |

| 4 | [DBUH][TFA] (10) | 9 | 9 |

| 5 | [DBUH]Cl (10) | 13 | 16 |

| 6 | [TBDH][Im] (10) | 5 | 9 |

| 7 | [TMGH][Im] (10) | 33 | 37 |

| 8 | [P4444][Im] (10) | 25 | 26 |

| 9 | [TBDH][TFE] (10) | 59 | 55 |

| 10 [c] | [TBDH][TFE] (10) | 57 | 58 |

| 11 [d] | [TBDH][TFE] (10) | 47 | 47 |

| 12 [e] | [TBDH][TFE] (10) | 56 | 53 |

| 13 | [TBDH][TFE] (15) | 94 | 97 |

| 14 | [TBDH][TFE] (20) | 44 | 46 |

| 15 | TBD (15) | trace | trace |

| 16 | TFE (15) | trace | trace |

| 17 | — | trace | trace |

| Entry | Substrate | Yield/% [b] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

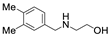

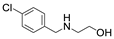

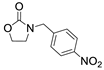

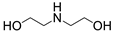

| 1 |  1a |  2a |  3a (94, 90c) |  4a (97, 93c) |

| 2 |  1a |  2b |  3a (80) |  4b (79) |

| 3 |  1a |  2c |  3a (73) |  4c (76) |

| 4 |  1a |  2d |  3a (99) |  4d (99) |

| 5 |  1a |  2e |  3a (61) |  4e (63) |

| 6 |  1b |  2a |  3b (89) |  4a (89) |

| 7 |  1c |  2a |  3c (85) |  4a (82) |

| 8 |  1d |  2a |  3d (99) |  4a (99) |

| 9 |  1e |  2a |  3e (82) |  4a (80) |

| 10 |  1f |  2a |  3f (24) |  4a (23) |

| 11 |  1g |  2a |  3g (93) |  4a (92) |

| 12 |  1h |  2a |  3h (95) |  4a (97) |

| 13 |  1i |  2a |  3i (58) |  4a (57) |

| 14 |  1j |  2a |  3j (94) |  4a (98) |

| Entry | IL | Yield/% [b] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | 3a | 4a | ||

| 1 | [DBUH][Im] | 87 | 97 | 99 |

| 2 | [DBUH][OAc] | 88 | 90 | 93 |

| 3 | [DBUH][TFE] | 46 | 63 | 62 |

| 4 | [DBUH][TFA] | 54 | 55 | 54 |

| 5 | [DBUH]Cl | 75 | 50 | 50 |

| 6 | [TBDH][Im] | 75 | 57 | 54 |

| 7 | [TMGH][Im] | 76 | 49 | 46 |

| 8 | [P4444][Im] | 34 | 44 | 43 |

| 9 | [TBDH][TFE] | 43 | 99 | 99 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xia, S.; Song, Y.; Li, X.; Li, H.; He, L.-N. Ionic Liquid-Promoted Three-Component Domino Reaction of Propargyl Alcohols, Carbon Dioxide and 2-Aminoethanols: A Thermodynamically Favorable Synthesis of 2-Oxazolidinones. Molecules 2018, 23, 3033. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23113033

Xia S, Song Y, Li X, Li H, He L-N. Ionic Liquid-Promoted Three-Component Domino Reaction of Propargyl Alcohols, Carbon Dioxide and 2-Aminoethanols: A Thermodynamically Favorable Synthesis of 2-Oxazolidinones. Molecules. 2018; 23(11):3033. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23113033

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Shumei, Yu Song, Xuedong Li, Hongru Li, and Liang-Nian He. 2018. "Ionic Liquid-Promoted Three-Component Domino Reaction of Propargyl Alcohols, Carbon Dioxide and 2-Aminoethanols: A Thermodynamically Favorable Synthesis of 2-Oxazolidinones" Molecules 23, no. 11: 3033. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23113033