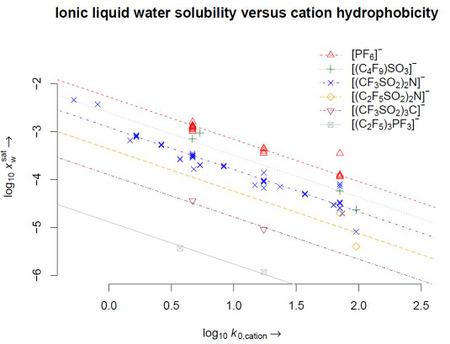

Explaining Ionic Liquid Water Solubility in Terms of Cation and Anion Hydrophobicity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theory

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Appendix

| Cation[a] | Anion[b] | Δest,exp | Temperature [K] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM16 | (C2F5)3PF3 | −5.93 | −5.98 | −0.05 | 293.15 |

| Pyr14 | (C2F5)3PF3 | −5.43 | −5.39 | 0.04 | 293.15 |

| Py8-4Me | (C2F5SO2)2N | −5.4 [21] | −5.11 | 0.29 | 298.15 |

| IM16 | (CF3SO2)3C | −5.04 | −4.99 | 0.05 | 293.15 |

| IM18 | (C2F5SO2)2N | −4.7 [23] | −4.99 | −0.29 | 298 |

| Py8-4Me | AsF6 | −4.91 [21] | −4.91 | 0 | 298.15 |

| Py8-4Me | (CF3SO2)2N | −5.09 [21] | −4.66 | 0.43 | 298.15 |

| Pyr18 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.71 [22] | −4.56 | 0.15 | 298 |

| IM18 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.5 [25] | −4.54 | −0.04 | 288.15 |

| IM18 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.59 | −4.54 | 0.05 | 293.15 |

| IM18 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.1 [27] | −4.54 | −0.44 | 293.15 |

| IM18 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.49 [25] | −4.54 | −0.05 | 293.15 |

| IM18 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.14 [24] | −4.54 | −0.4 | 296.5 |

| IM18 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.1 [26] | −4.54 | −0.44 | 298 |

| IM18 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.6 [23] | −4.54 | 0.06 | 298 |

| IM18 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.47 [25] | −4.54 | −0.07 | 298.15 |

| Py6-4NMe2 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.53 | −4.5 | 0.03 | 293.15 |

| Py6-4NMe2 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.53 [24] | −4.5 | 0.03 | 296.5 |

| IM14 | (CF3SO2)3C | −4.44 [24] | −4.49 | −0.05 | 296.5 |

| Py8-4Me | (C4F9)SO3 | −4.63 [21] | −4.35 | 0.28 | 298.15 |

| IM17 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.31 [25] | −4.29 | 0.02 | 288.15 |

| IM17 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.3 [25] | −4.29 | 0.01 | 293.15 |

| IM17 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.29 [25] | −4.29 | 0 | 298.15 |

| IM18 | (C4F9)SO3 | −4.23 [26] | −4.24 | −0.01 | 298 |

| IM16-2Me | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.15 [24] | −4.12 | 0.03 | 296.5 |

| IM16 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.05 [25] | −4 | 0.05 | 288.15 |

| IM16 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.18 | −4 | 0.18 | 293.15 |

| IM16 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.86 [27] | −4 | −0.14 | 293.15 |

| IM16 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.05 [25] | −4 | 0.05 | 293.15 |

| IM16 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.03 [24] | −4 | 0.03 | 296.5 |

| IM16 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.02 [25] | −4 | 0.02 | 298.15 |

| Pyr16 | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.12 | −3.94 | 0.18 | 293.15 |

| IM18 | PF6 | −3.95 [28] | −3.91 | 0.04 | 288.15 |

| IM18 | PF6 | −3.92 [28] | −3.91 | 0.01 | 293.15 |

| IM18 | PF6 | −3.93 | −3.91 | 0.02 | 293.15 |

| IM18 | PF6 | −3.46 [30] | −3.91 | −0.45 | 295 |

| IM18 | PF6 | −3.9 [28] | −3.91 | −0.01 | 298.15 |

| IM15 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.74 [25] | −3.72 | 0.02 | 288.15 |

| IM15 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.73 [25] | −3.72 | 0.01 | 293.15 |

| IM15 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.71 [25] | −3.72 | −0.01 | 298.15 |

| Py8-4Me | PhBF3 | −3.6 [21] | −3.6 | 0 | 298.15 |

| Py4-3Me | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.7 [24] | −3.55 | 0.15 | 296.5 |

| Py4-4Me | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.69 [26] | −3.55 | 0.14 | 298 |

| Pip14 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.78 [22] | −3.51 | 0.27 | 298 |

| IM14 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.54 [25] | −3.5 | 0.04 | 288.15 |

| IM14 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.5 | −3.5 | 0 | 293.15 |

| IM14 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.53 [25] | −3.5 | 0.03 | 293.15 |

| IM14 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.46 [27] | −3.5 | −0.04 | 293.15 |

| IM14 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.49 [29] | −3.5 | −0.01 | 294.15 |

| IM14 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.5 [24] | −3.5 | 0 | 296.5 |

| IM14 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.51 [26] | −3.5 | 0.01 | 298 |

| IM14 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.51 [25] | −3.5 | 0.01 | 298.15 |

| Pyr14 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.57 | −3.41 | 0.16 | 293.15 |

| Pyr14 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.59 [22] | −3.41 | 0.18 | 298 |

| IM16 | PF6 | −3.45 [28] | −3.37 | 0.08 | 288.15 |

| IM16 | PF6 | −3.35 | −3.37 | −0.02 | 293.15 |

| IM16 | PF6 | −3.41 [28] | −3.37 | 0.04 | 293.15 |

| IM16 | PF6 | −3.36 [28] | −3.37 | −0.01 | 298.15 |

| IM13 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.29 [25] | −3.28 | 0.01 | 288.15 |

| IM13 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.28 [25] | −3.28 | 0 | 293.15 |

| IM13 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.27 [25] | −3.28 | −0.01 | 298.15 |

| Py4-4Me | (C4F9)SO3 | −3.03 [26] | −3.25 | −0.22 | 298 |

| IM14 | (C4F9)SO3 | −3.15 [26] | −3.2 | −0.05 | 298 |

| IM12 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.12 [25] | −3.1 | 0.02 | 288.15 |

| IM12 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.08 [27] | −3.1 | −0.02 | 293.15 |

| IM12 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.1 [25] | −3.1 | 0 | 293.15 |

| IM12 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.1 [24] | −3.1 | 0 | 296.5 |

| IM12 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.08 [25] | −3.1 | −0.02 | 298.15 |

| Py8-4Me | CF3SO3 | −3.09 [21] | −3.09 | 0 | 298.15 |

| Mor11O2 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.19 | −3.06 | 0.13 | 293.15 |

| Py8-4Me | BF4 | −2.98 [21] | −3.01 | −0.03 | 298.15 |

| IM18 | BF4 | −2.93 [30] | −2.9 | 0.03 | 295 |

| IM14 | PF6 | −3 [28] | −2.87 | 0.13 | 288.15 |

| IM14 | PF6 | −2.8 [27] | −2.87 | −0.07 | 293.15 |

| IM14 | PF6 | −2.9 | −2.87 | 0.03 | 293.15 |

| IM14 | PF6 | −2.96 [28] | −2.87 | 0.09 | 293.15 |

| IM14 | PF6 | −2.93 [31] | −2.87 | 0.06 | 294 |

| IM14 | PF6 | −2.87 [29] | −2.87 | 0 | 294.15 |

| IM14 | PF6 | −2.89 [30] | −2.87 | 0.02 | 295 |

| IM14 | PF6 | −2.9 [24] | −2.87 | 0.03 | 296.5 |

| IM14 | PF6 | −2.92 [28] | −2.87 | 0.05 | 298.15 |

| Py3OH | (CF3SO2)2N | −2.43 | −2.83 | −0.4 | 293.15 |

| IM12OH | (CF3SO2)2N | −2.34 [24] | −2.66 | −0.32 | 296.5 |

| IM12 | B(CN)4 | −2.46 [24] | −2.46 | 0 | 296.5 |

| N4444 | (6-2Et)2SS | −1.52 [32] | −1.52 | 0 | 298 |

References and Notes

- Walden, P. Ueber die Molekulargrösse und elektrische Leitfähigkeit einiger geschmolzener Salze (Molecular weights and electrical conductivity of several fused salts). Bull Acad. Imper. Sci. St. Petersburg 1914, 8, 405–422. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes, JS; Zaworotko, MJ. Air and water stable 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium based ionic liquids. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Comm 1992, 1992, 965–967. [Google Scholar]

- Heintz, A. Recent developments in thermodynamics and thermophysics of non-aqueous mixtures containing ionic liquids. A review. J. Chem. Thermodyn 2005, 37, 525–535. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, R; Kragl, U. Do we understand the volatility of ionic liquids? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2007, 46, 6582–6584. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, R; Kragl, U. Verstehen wir die Flüchtigkeit ionischer Flüssigkeiten? Angew. Chem 2007, 119, 6702–6704. [Google Scholar]

- Rebelo, LP; Lopes, JN; Esperanca, JM; Guedes, HJ; Lachwa, J; Najdanovic-Visak, V; Visak, ZP. Accounting for the unique, doubly dual nature of ionic liquids from a molecular thermodynamic and modeling standpoint. Acc. Chem. Res 2007, 40, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Padua, AA; Costa Gomes, MF; Canongia-Lopes, JN. Molecular solutes in ionic liquids: a structural perspective. Acc. Chem. Res 2007, 40, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Weingärtner, H. Understanding ionic liquids at the molecular level: Facts, problems, and controversies. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2008, 47, 654–670. [Google Scholar]

- Deetlefs, M; Seddon, KR; Shara, M. Predicting physical properties of ionic liquids. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2006, 8, 642–649. [Google Scholar]

- Slattery, JM; Daguenet, C; Dyson, PJ; Schubert, TJ; Krossing, I. How to predict the physical properties of ionic liquids: a volume-based approach. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2007, 46, 5384–5388. [Google Scholar]

- Lynden-Bell, RM; Del Popolo, MG; Youngs, TG; Kohanoff, J; Hanke, CG; Harper, JB; Pinilla, CC. Simulations of ionic liquids, solutions, and surfaces. Acc. Chem. Res 2007, 40, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone, S; Malvaldi, M; Chiappe, C. A RISM approach to the liquid structure and solvation properties of ionic liquids. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2007, 9, 5576–5581. [Google Scholar]

- Couling, DJ; Bernot, RJ; Docherty, KM; Dixon, JK; Maginn, EJ. Assessing the factors responsible for ionic liquid toxicity to aquatic organisms via quantitative structure - property relationship modeling. Green Chem 2006, 8, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ranke, J; Stock, F; Müller, A; Stolte, S; Störmann, R; Bottin-Weber, U; Jastorff, B. Lipophilicity parameters for ionic liquid cations and their correlation to in vitro cytotoxicity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety 2007, 67, 430–438. [Google Scholar]

- García-Lorenzo, A; Tojo, E; Tojo, J; Teijeira, M; Rodríguez-Berrocal, FJ; Pérez González, M; Martínez-Zorzano, VS. Cytotoxicity of selected imidazolium-derived ionic liquids in the human Caco-2 cell line. Substructural toxicological interpretation through a QSAR study. Green Chem 2008, 10, 508–516. [Google Scholar]

- Ranke, J; Stolte, S; Stormann, R; Arning, J; Jastorff, B. Design of sustainable chemical products — the example of ionic liquids. Chem. Rev 2007, 107, 2183–2206. [Google Scholar]

- Harjani, JR; Singer, RD; Garcia, MT; Scammells, PJ. The design and synthesis of biodegradable pyridinium ionic liquids. Green Chem 2008, 10, 436–438. [Google Scholar]

- Kalidas, C; Hefter, G; Marcus, Y. Gibbs energies of transfer of cations from water to mixed aqueous organic solvents. Chem. Rev 2000, 100, 819–852. [Google Scholar]

- Stolte, S; Arning, J; Bottin-Weber, U; Pitner, W; Welz-Biermann, U; Jastorff, B; Ranke, J. Effects of different head groups and modified side chains on the cytotoxicity of ionic liquids. Green Chem 2007, 9, 760–767. [Google Scholar]

- Branco, LC; Rosa, JN; Ramos, JJM; Afonso, CAM. Preparation and characterization of new room temperature ionic liquids. Chem. Eur. J 2002, 8, 3671–3677. [Google Scholar]

- Papaiconomou, N; Salminen, J; Lee, J-M; Prausnitz, JM. Physicochemical properties of hydrophobic ionic liquids containing 1-octylpyridinium, 1-octyl-2-methylpyridinium, or 1-octyl-4-methylpyridinium cations. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2007, 52, 833–840. [Google Scholar]

- Salminen, J; Papaiconomou, N; Kumara, RA; Lee, J; Kerr, J; Newmana, J; Prausnitz, JM. Physicochemical properties and toxicities of hydrophobic piperidinium and pyrrolidinium ionic liquids. Fluid Phase Equilib 2007, 261, 421–426. [Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi, T; Tsujioka, N; Kurita, S; Iwami, Y. Phase-boundary potential across the nonpolarized interface between the room-temperature molten salt and water. Electrochem. Commun 2003, 5, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Chapeaux, A; Simoni, LD; Stadtherr, MA; Brennecke, JF. Liquid phase behavior of ionic liquids with water and 1-Octanol and modeling of 1-Octanol/Water partition coefficients. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2007, 52, 2462–2467. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, MG; Carvalho, PJ; Gardas, RL; Marrucho, IM; Santos, LMNBF; Coutinho, JAP. Mutual solubilities of water and the [c(n)mim][tf(2)n] hydrophobic ionic liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 1604–1610. [Google Scholar]

- Papaiconomou, N; Yakelis, N; Salminen, J; Bergman, R; Prausnitz, JM. Synthesis and properties of seven ionic liquids containing 1-methyl-3-octylimidazolium or 1-butyl-4-methylpyridinium cations. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2006, 51, 1389–1393. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H; Dai, S; Bonnesen, PV. Solvent extraction of Sr2+ and Cs+ based on room-temperature ionic liquids containing monoaza-substituted crown ethers. Anal. Chem 2004, 76, 2773–2779. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, MG; Neves, CMSS; Carvalho, PJ; Gardas, RL; Fernandes, AM; Marrucho, IM; Santos, LMNBF; Coutinho, JAP. Mutual solubilities of water and hydrophobic ionic liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 13082–13089. [Google Scholar]

- Shvedene, NV; Borovskaya, SV; Sviridov, VV; Ismailova, ER; Pletnev, IV. Measuring the solubilities of ionic liquids in water using ion-selective electrodes. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2005, 381, 427–430. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, JL; Maginn, EJ; Brennecke, JF. Solution thermodynamics of imidazolium-based ionic liquids and water. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 10942–10949. [Google Scholar]

- Carda-Broch, S; Berthod, A; Armstrong, DW. Solvent properties of the 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate ionic liquid. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2003, 375, 191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Nishi, N; Kawakami, T; Shigematsu, F; Yamamoto, M; Kakiuchi, T. Fluorine-free and hydrophobic room-temperature ionic liquids, tetraalkylammonium bis(2-ethylhexyl)sulfosuccinates, and their ionic liquid-water two-phase properties. Green Chem 2006, 8, 349–355. [Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi, T. Ionic-liquid vertical bar water two-phase systems. Anal. Chem 2007, 79, 6442–6449. [Google Scholar]

IM1n |  Mor11O2 |  Py3OH |

IM14 |  N4444 |  Py4-3Me |

IM12OH |  Pip14 |  Pyn-4Me |

IM16-2Me |  Pyr1n |  Py6-4NMe2 |

| Ionic liquid | Acronym |

|---|---|

| 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride | IM12 Cl |

| 1-(3-hydroxypropyl)pyridinium chloride | Py3OH Cl |

| 4-(ethoxymethyl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride | Mor11O2 Cl |

| 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate | IM14 PF6 |

| 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide | IM14 (CF3SO2)2N |

| 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate | IM16 PF6 |

| 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide | IM16 (CF3SO2)2N |

| 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium tris(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)methide | IM16 (CF3SO2)3C |

| 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluorotris(pentafluoroethyl)phosphate | IM16 (C2F5)3PF3 |

| 1-octyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate | IM18 PF6 |

| 1-octyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide | IM18 (CF3SO2)2N |

| 1-(3-hydroxypropyl)pyridinium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide | Py3OH (CF3SO2)2N |

| 4-(dimethylamino)-1-hexylpyridinium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide | Py6-4NMe2 (CF3SO2)2N |

| 1-butyl-1-methylpyrrolidinium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide | Pyr14 (CF3SO2)2N |

| 1-butyl-1-methylpyrrolidinium trifluorotris(pentafluoroethyl)phosphate | Pyr16 (C2F5)3PF3 |

| 1-hexyl-1-methylpyrrolidinium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide | Pyr16 (CF3SO2)2N |

| Cation hydrophobicity

| IL water solubility

| |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cation[a] | log k0,c | Anion[b] | T [K] | |

| IM16 | 1.2 [14] | (C2F5)3PF3 | −5.93 | 293.15 |

| Pyr14 | 0.57 [14] | (C2F5)3PF3 | −5.43 | 293.15 |

| Py8-4Me | 2 [14] | (C2F5SO2)2N | −5.4 | 298.15 [21] |

| Py8-4Me | 2 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −5.09 | 298.15 [21] |

| IM16 | 1.2 [14] | (CF3SO2)3C | −5.04 | 293.15 |

| Py8-4Me | 2 [14] | AsF6 | −4.91 | 298.15 [21] |

| Pyr18 | 1.9 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.71 | 298 [22] |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | (C2F5SO2)2N | −4.7 | 298 [23] |

| Py8-4Me | 2 [14] | (C4F9)SO3 | −4.63 | 298.15 [21] |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.6 | 298 [23] |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.59 | 293.15 |

| Py6-4NMe2 | 1.8 [19] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.53 | 293.15 |

| Py6-4NMe2 | 1.8 [19] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.53 | 296.5 [24] |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.5 | 288.15 [25] |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.49 | 293.15 [25] |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.47 | 298.15 [25] |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | (CF3SO2)3C | −4.44 | 296.5 [24] |

| IM17 | 1.6 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.31 | 288.15 [25] |

| IM17 | 1.6 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.3 | 293.15 [25] |

| IM17 | 1.6 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.29 | 298.15 [25] |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | (C4F9)SO3 | −4.23 | 298 [26] |

| IM16 | 1.2[14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.18 | 293.15 |

| IM16-2Me | 1.4 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.15 | 296.5 [24] |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.14 | 296.5 [24] |

| Pyr16 | 1.2 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.12 | 293.15 |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.1 | 298 [26] |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.1 | 293.15 [27] |

| IM16 | 1.2 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.05 | 288.15 [25] |

| IM16 | 1.2 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.05 | 293.15 [25] |

| IM16 | 1.2 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.03 | 296.5 [24] |

| IM16 | 1.2 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −4.02 | 298.15 [25] |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | PF6 | −3.95 | 288.15 [28] |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | PF6 | −3.93 | 293.15 |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | PF6 | −3.92 | 293.15 [28] |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | PF6 | −3.9 | 298.15 [28] |

| IM16 | 1.2 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.86 | 293.15 [27] |

| Pip14 | 0.68 [19] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.78 | 298 [22] |

| IM15 | 0.92 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.74 | 288.15 [25] |

| IM15 | 0.92 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.73 | 293.15 [25] |

| IM15 | 0.92 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.71 | 298.15 [25] |

| Py4-3Me | 0.73 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.7 | 296.5 [24] |

| Py4-4Me | 0.73 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.69 | 298 [26] |

| Py8-4Me | 2 [14] | PhBF3 | −3.6 | 298.15 [21] |

| Pyr14 | 0.57 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.59 | 298 [22] |

| Pyr14 | 0.57 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.57 | 293.15 |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.54 | 288.15 [25] |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.53 | 293.15 [25] |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.51 | 298.15 [25] |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.51 | 298 [26] |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.5 | 296.5 [24] |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.5 | 293.15 |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.49 | 294.15 [29] |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.46 | 293.15 [27] |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | PF6 | −3.46 | 295 [30] |

| IM16 | 1.2 [14] | PF6 | −3.45 | 288.15 [28] |

| IM16 | 1.2 [14] | PF6 | −3.41 | 293.15 [28] |

| IM16 | 1.2 [14] | PF6 | −3.36 | 298.15 [28] |

| IM16 | 1.2 [14] | PF6 | −3.35 | 293.15 |

| IM13 | 0.42 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.29 | 288.15 [25] |

| IM13 | 0.42 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.28 | 293.15 [25] |

| IM13 | 0.42 [14] | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.27 | 298.15 [25] |

| Mor11O2 | 0.17 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.19 | 293.15 |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | (C4F9)SO3 | −3.15 | 298 [26] |

| IM12 | 0.22 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.12 | 288.15 [25] |

| IM12 | 0.22 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.1 | 296.5 [24] |

| IM12 | 0.22 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.1 | 293.15 [25] |

| Py8-4Me | 2 [14] | CF3SO3 | −3.09 | 298.15 [21] |

| IM12 | 0.22 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.08 | 293.15 [27] |

| IM12 | 0.22 | (CF3SO2)2N | −3.08 | 298.15 [25] |

| Py4-4Me | 0.73 [14] | (C4F9)SO3 | −3.03 | 298 [26] |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | PF6 | −3 | 288.15 [28] |

| Py8-4Me | 2 [14] | BF4 | −2.98 | 298.15 [21] |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | PF6 | −2.96 | 293.15 [28] |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | PF6 | −2.93 | 294 [31] |

| IM18 | 1.9 [14] | BF4 | −2.93 | 295 [30] |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | PF6 | −2.92 | 298.15 [28] |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | PF6 | −2.9 | 293.15 |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | PF6 | −2.9 | 296.5 [24] |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | PF6 | −2.89 | 295 [30] |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | PF6 | −2.87 | 294.15 [29] |

| IM14 | 0.67 [14] | PF6 | −2.8 | 293.15 [27] |

| IM12 | 0.22 | B(CN)4 | −2.46 | 296.5 [24] |

| Py3OH | −0.09 | (CF3SO2)2N | −2.43 | 293.15 |

| IM12OH | −0.28 [19] | (CF3SO2)2N | −2.34 | 296.5 [24] |

| N4444 | 2.3 [14] | (6-2Et)2SS | −1.52 | 298 [32] |

| Parameter | UFT data only | Full dataset |

|---|---|---|

| m | 0.97 | 0.881 |

| c(6-2Et)2SS | 0.521 (1) | |

| cBF4 | −1.268 (2) | |

| cCF3SO3 | −1.343 (1) | |

| cC(CN)3 | −1.642 (3) | |

| cPhBF3 | −1.853 (1) | |

| cB(CN)4 | −2.264 (1) | |

| cPF6 | −2.178 (3) | −2.28 (18) |

| c(C4F9)SO3 | −2.61 (4) | |

| c(CF3SO2)2N | −2.868 (8) | −2.911 (50) |

| cAsF6 | −3.165 (1) | |

| c(C2F5SO2)2N | −3.363 (2) | |

| c(CF3SO2)3C | −3.841 (1) | −3.902 (2) |

| c(C2F5)3PF3 | −4.803 (2) | −4.883 (2) |

| n | 14 | 88 |

| df | 9 | 74 |

| R2 | 0.999 | 0.998 |

| RSE | 0.157 | 0.16 |

© 2009 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Ranke, J.; Othman, A.; Fan, P.; Müller, A. Explaining Ionic Liquid Water Solubility in Terms of Cation and Anion Hydrophobicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 1271-1289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms10031271

Ranke J, Othman A, Fan P, Müller A. Explaining Ionic Liquid Water Solubility in Terms of Cation and Anion Hydrophobicity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2009; 10(3):1271-1289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms10031271

Chicago/Turabian StyleRanke, Johannes, Alaa Othman, Ping Fan, and Anja Müller. 2009. "Explaining Ionic Liquid Water Solubility in Terms of Cation and Anion Hydrophobicity" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 10, no. 3: 1271-1289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms10031271