Thermal Denaturation and Aggregation of Myosin Subfragment 1 Isoforms with Different Essential Light Chains

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. New Approach to Analysis of Irreversible Denaturation of Multidomain Proteins

2.1. Theory

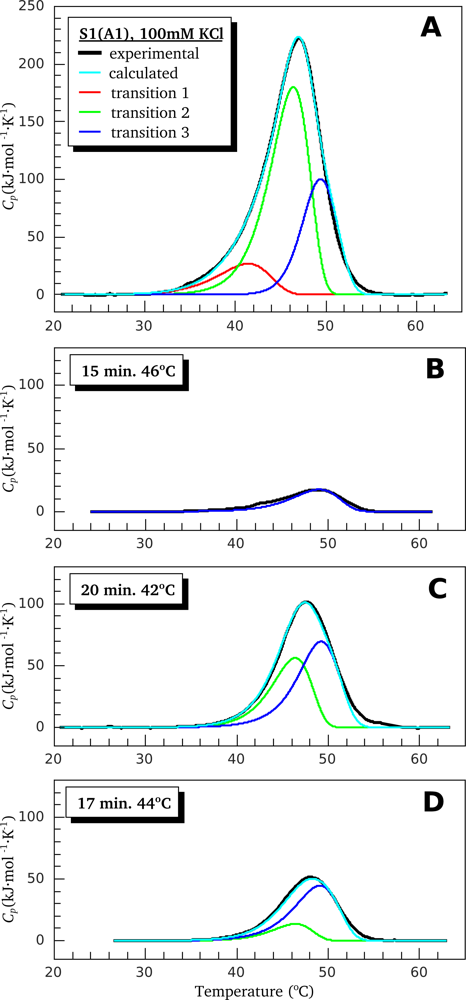

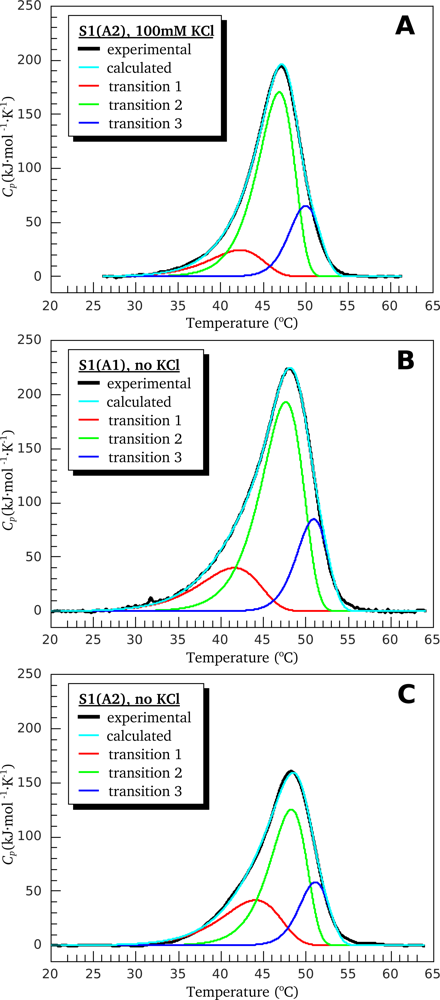

2.2. Resolving Power of the Method. Selection of the Annealing Conditions

3. Results and Discussion

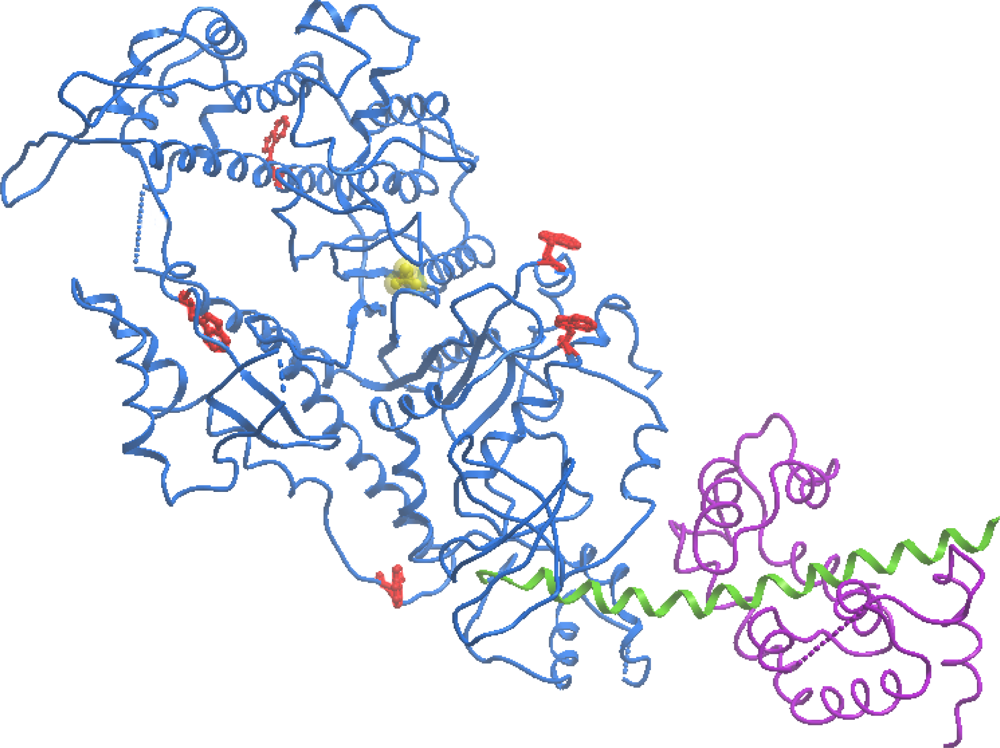

3.1. Thermal Denaturation of Myosin S1 Isoforms Studied by DSC

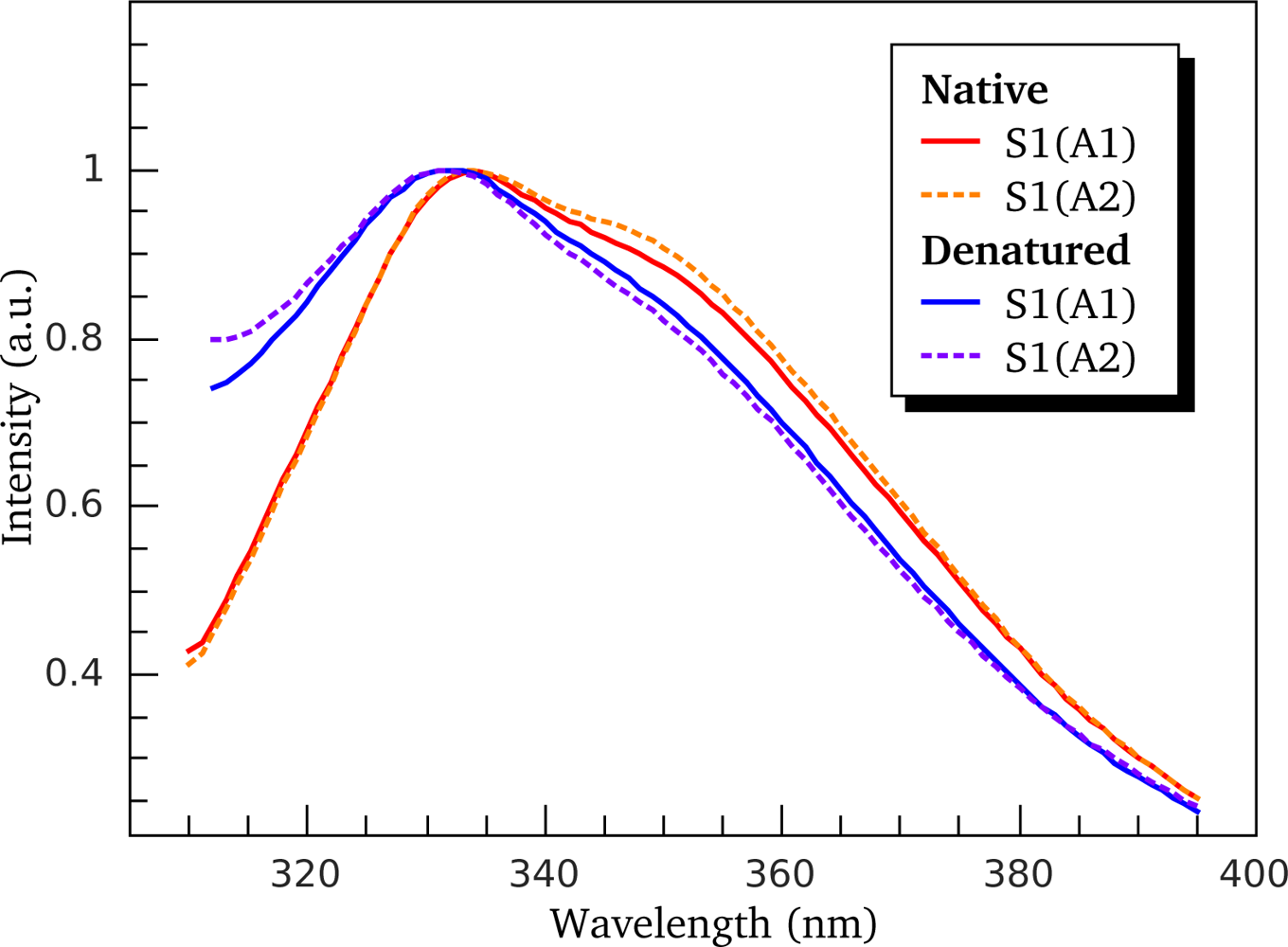

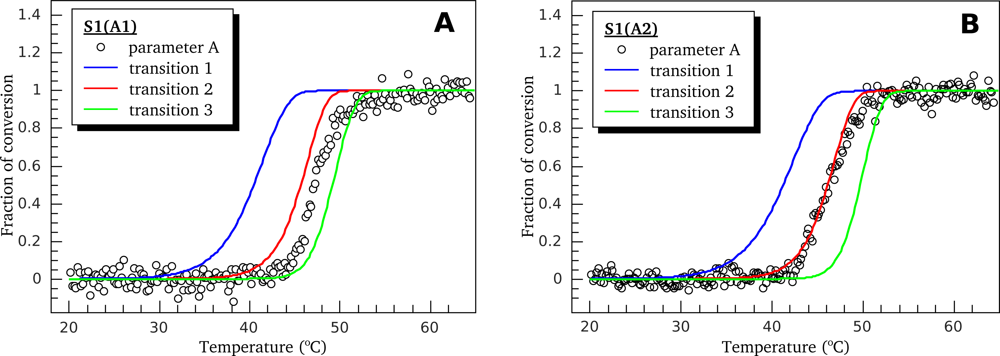

3.2. Thermally-Induced Changes in the Intrinsic Fluorescence of S1 Isoforms

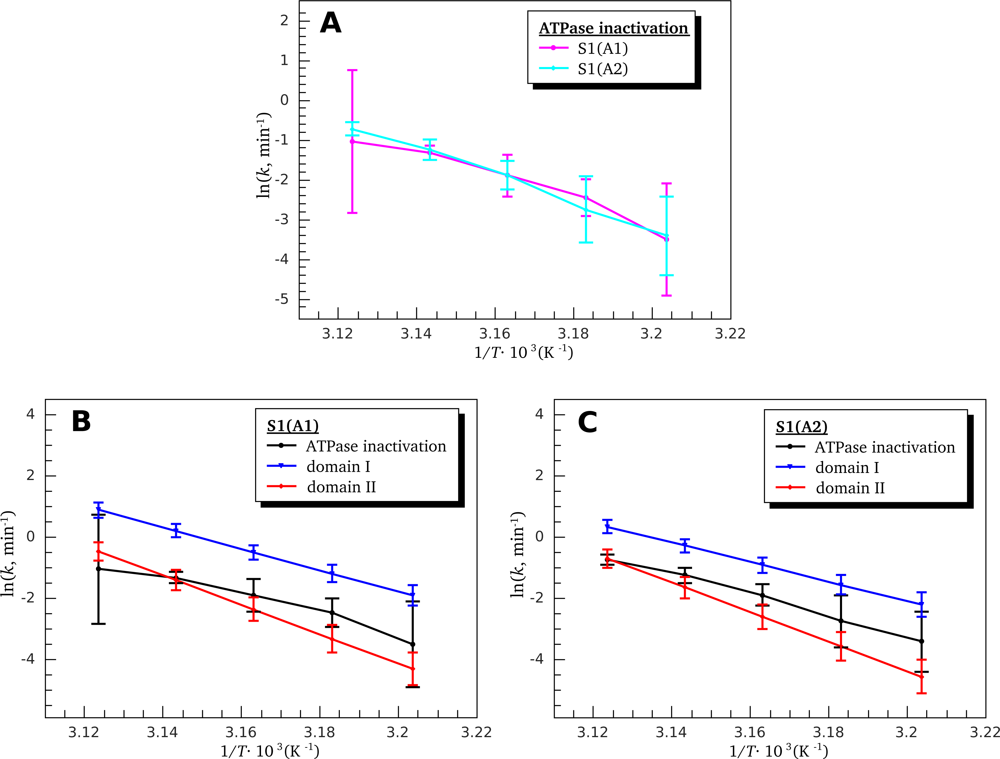

3.3. Heat-Induced Inactivation of S1 ATPase

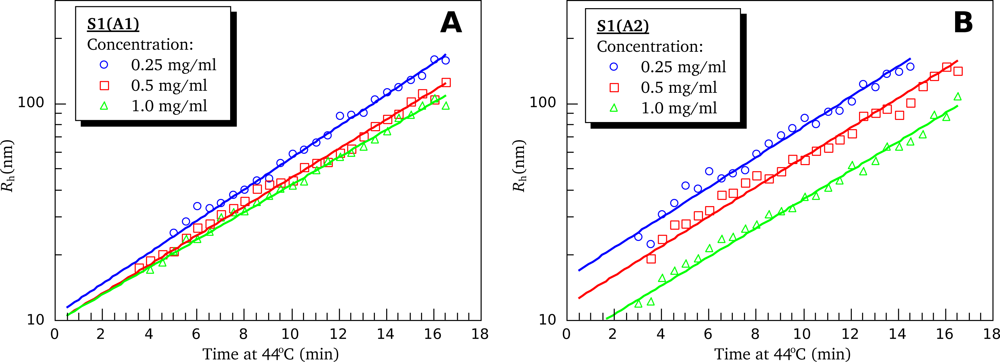

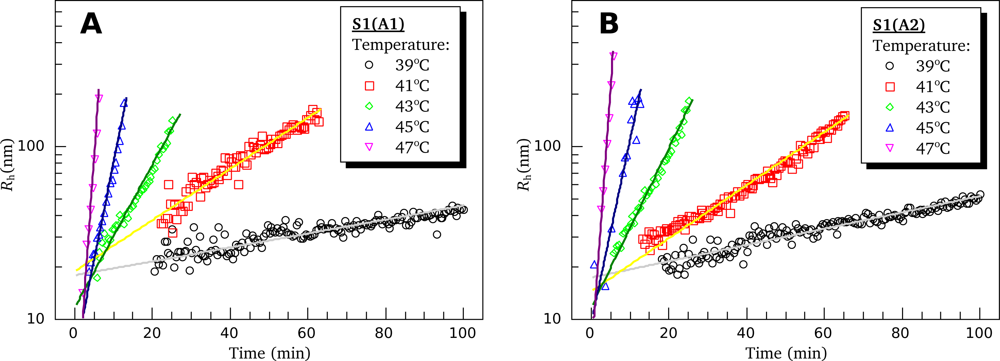

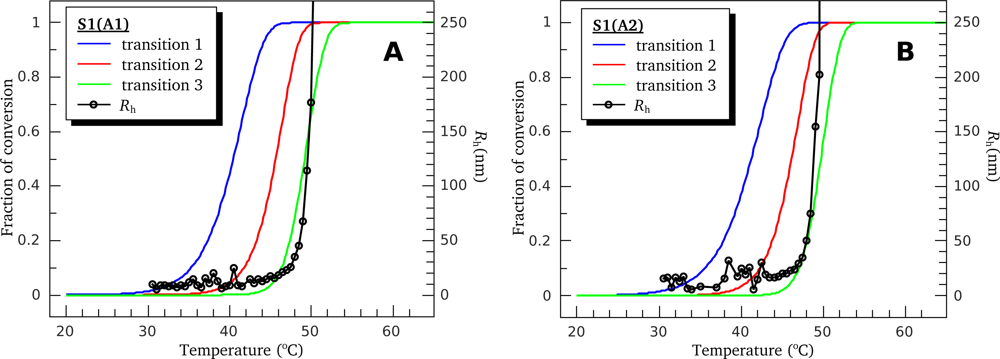

3.4. Heat-Induced Aggregation of S1 Isoforms

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Protein Preparations

4.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

4.3. Estimation of Chemical Base Line in DSC Experiments

4.4. Intrinsic Fluorescence

4.5. ATPase Inactivation

4.6. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

4.7. Calculation Procedures

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Rayment, I; Rypniewski, WP; Schmidt-Base, K; Smith, R; Tomchick, DR; Benning, MM; Winkelmann, DA; Wesenberg, G; Holden, HM. Three-dimensional structure of myosin subfragment 1: a molecular motor. Science 1993, 261, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rayment, I. The structural basis of the myosin ATPase activity. J. Biol. Chem 1996, 271, 15850–15853. [Google Scholar]

- Uyeda, TQ; Abramson, PD; Spudich, JA. The neck region of the myosin motor domain acts as a lever arm to generate movement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 4459–4464. [Google Scholar]

- Weeds, AG; Taylor, RS. Separation of subfragment-1 isoenzymes from rabbit skeletal muscle myosin. Nature 1975, 257, 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, G; Weeds, AG. The amino-acid sequence of the alkali light chains of rabbit skeletal muscle myosin. Eur. J. Biochem 1974, 44, 317–334. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, PD; Slayter, CS; Pope, B; Weeds, AG. Studies on the actin activation of myosin subfragment-1 isoenzymes and the role of the myosin light chains. Eur. J. Biochem 1979, 99, 385–394. [Google Scholar]

- Chalovich, JM; Stein, LA; Greene, LE; Eisenberg, E. Interaction of isozymes of myosin subfragment 1 with actin: effect of ionic strength and nucleotide. Biochemistry 1984, 23, 4885–4889. [Google Scholar]

- Sutoh, K. Identification of myosin-binding sites on the actin sequence. Biochemistry 1982, 21, 3654–3661. [Google Scholar]

- Trayer, IP; Trayer, HR; Levine, BA. Evidence that the N-terminal region of A1-light chain of myosin interacts directly with the C-terminal region of actin. A proton magnetic resonance study. Eur. J. Biochem 1987, 164, 259–266. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashibara, T; Miyanishi, T. Binding of the amino-terminal region of myosin alkali 1 light chain to actin and its effect on actin-myosin interaction. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 12821–12827. [Google Scholar]

- Andreev, OA; Saraswat, LD; Lowey, S; Slaughter, C; Borejdo, J. Interaction of the N-terminus of chicken skeletal essential light chain 1 with F-actin. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 2480–2485. [Google Scholar]

- Pliszka, B; Redowicz, MJ; Stepkowski, D. Interaction of the N-terminal part of the A1 essential light chain with the myosin heavy chain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2001, 281, 924–928. [Google Scholar]

- Borejdo, J; Ushakov, DS; Moreland, R; Akopova, I; Reshetnyak, Y; Saraswat, LD; Kamm, K; Lowey, S. The power stroke causes changes in the orientation and mobility of the termini of essential light chain 1 of myosin. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 3796–3803. [Google Scholar]

- Lowey, S; Saraswat, LD; Liu, H; Volkmann, N; Hanein, D. Evidence for an interaction between the SH3 domain and the N-terminal extension of the essential light chain in class II myosins. J. Mol. Biol 2007, 371, 902–913. [Google Scholar]

- Mrakovcic-Zenic, A; Oriol-Audit, C; Reisler, E. On the alkali light chains of vertebrate skeletal myosin. Nucleotide binding and salt-induced conformational changes. Eur. J. Biochem 1981, 115, 565–570. [Google Scholar]

- Levitsky, DI; Nikolaeva, OP; Vedenkina, NS; Shnyrov, VL; Golitsina, NL; Khvorov, NV; Permyakov, EA; Poglazov, BF. The effect of alkali light chains on the thermal stability of myosin subfragment 1. Biomed. Sci 1991, 2, 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- Abillon, E; Bremier, L; Cardinaud, R. Conformational calculations on the Ala14-Pro27 LC1 segment of rabbit skeletal myosin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1990, 1037, 394–400. [Google Scholar]

- Kurganov, BI; Lyubarev, AE; Sanchez-Ruiz, JM; Shnyrov, VL. Analysis of differential scanning calorimetry data for proteins. Criteria of validity of one-step mechanism of irreversible protein denaturation. Biophys. Chem 1997, 69, 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Levitsky, DI; Khvorov, NV; Shnyrov, VL; Vedenkina, NS; Permyakov, EA; Poglazov, BF. Domain structure of myosin subfragment-1. Selective denaturation of the 50 kDa segment. FEBS Lett 1990, 264, 176–178. [Google Scholar]

- Levitsky, DI; Shnyrov, VL; Khvorov, NV; Bukatina, AE; Vedenkina, NS; Permyakov, EA; Nikolaeva, OP; Poglazov, BF. Effects of nucleotide binding on thermal transitions and domain structure of myosin subfragment 1. Eur. J. Biochem 1992, 209, 829–835. [Google Scholar]

- Levitsky, DI. Domain Structure of the Myosin Head. In Soviet Scientific Reviews Section D: Physico-Chemical Biology; Harwood Academic Publishers GmbH: Newark, NJ, USA, 1994; Volume 12, pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, SW; Elzinga, M. Amino acid sequence of rabbit skeletal muscle myosin. 50-kDa fragment of the heavy chain. J. Biol. Chem 1990, 265, 4893–4901. [Google Scholar]

- Permyakov, EA; Burstein, EA. Some aspects of studies of thermal transitions in proteins by means of their intrinsic fluorescence. Biophys. Chem 1984, 19, 265–271. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova, IM; Stepanenko, OV; Stepanenko, OV; Povarova, OI; Biktashev, AG; Verkhusha, VV; Shavlovsky, MM; Turoverov, KK. The place of inactivated actin and its kinetic predecessor in actin folding-unfolding. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 13127–13132. [Google Scholar]

- Khanova, HA; Markossian, KA; Kurganov, BI; Samoilov, AM; Kleimenov, SYu; Levitsky, DI; Yudin, IK; Timofeeva, AC; Muranov, KO; Ostrovsky, MA. Mechanism of chaperone-like activity. Suppression of thermal aggregation of beta-L-crystallin by alpha-crystallin. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 15480–15487. [Google Scholar]

- Markossian, KA; Khanova, HA; Kleimenov, SYu; Levitsky, DI; Chebotareva, NA; Asryants, RA; Muronetz, VI; Saso, L; Yudin, IK; Kurganov, BI. Mechanism of thermal aggregation of rabbit muscle glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 13375–13384. [Google Scholar]

- Markossian, KA; Yudin, IK; Kurganov, BI. Mechanism of suppression of protein aggregation by alpha-crystallin. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2009, 10, 1314–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Trayer, HR; Trayer, IP. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer within the complex formed by actin and myosin subfragment 1. Comparison between weakly and strongly attached states. Biochemistry 1988, 27, 5718–5727. [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli, UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaeva, OP; Orlov, VN; Bobkov, AA; Levitsky, DI. Differential scanning calorimetric study of myosin subfragment 1 with tryptic cleavage at the N-terminal region of the heavy chain. Eur. J. Biochem 2002, 269, 5678–5688. [Google Scholar]

- Shakirova, LI; Mikhailova, VV; Siletskaya, EI; Timofeev, VP; Levitsky, DI. Nucleotide-induced and actin-induced structural changes in SH1-SH2-modified myosin subfragment 1. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil 2007, 28, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Markov, DI; Pivovarova, AV; Chernik, IS; Gusev, NB; Levitsky, DI. Small heat shock protein Hsp27 protects myosin S1 from heat-induced aggregation, but not from thermal denaturation and ATPase inactivation. FEBS Lett 2008, 582, 1407–1412. [Google Scholar]

- Kremneva, E; Nikolaeva, O; Maytum, R; Arutyunyan, AM; Kleimenov, SYu; Geeves, MA; Levitsky, DI. Thermal unfolding of smooth muscle and non-muscle tropomyosin alpha-homodimers with alternatively spliced exons. FEBS J 2006, 273, 588–600. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Mayorga, O; Freire, E. Dynamic analysis of differential scanning calorimetry data. Biophys. Chem 1987, 27, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Filimonov, VV; Potekhin, SA; Matveev, SV; Privalov, PL. Thermodynamic analysis of scanning microcalorimetry data. 1. Algorithms for deconvolution of heat absorption curves. Mol Biol (Mosk) 1982, 16, 551–562. (in Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Turoverov, KK; Haitlina, SYu; Pinaev, GP. Ultra-violet fluorescence of actin. Determination of native actin content in actin preparations. FEBS Lett 1976, 62, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Turoverov, KK; Kuznetsova, IM. Intrinsic fluorescence of actin. J. Fluoresc 2003, 13, 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Staiano, M; Scognamiglio, V; Rossi, M; D’Auria, S; Stepanenko, OV; Kuznetsova, IM; Turoverov, KK. Unfolding and refolding of the glutamine-binding protein from Escherichia coli and its complex with glutamine induced by guanidine hydrochloride. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 5625–5633. [Google Scholar]

- Panusz, HT; Graczyk, G; Wilmanska, D; Skarzynski, J. Analysis of orthophosphate-pyrophosphate mixtures resulting from weak pyrophosphatase activities. Anal. Biochem 1970, 35, 494–504. [Google Scholar]

- Markov, DI; Nikolaeva, OP; Levitsky, DI. Effects of myosin “essential” light chain A1 on aggregation properties of the myosin head. Acta Naturae 2010, 2(2(5)), 77–81. [Google Scholar]

| High ionic strength conditions (100 mM KCl) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Domain I (transition 1) | Domain II (transition 2) | Domain II (transition 3) | |||

| S1(A1) | S1(A2) | S1(A1) | S1(A2) | S1(A1) | S1(A2) | |

| T*, K | 317.5 ± 0.4 | 319.0 ± 0.4 | 321.2 ± 0.4 | 321.6 ± 0.4 | 324.5 ± 0.4 | 324.7 ± 0.4 |

| Ea, kJ/mole | 290 ± 40 | 265 ± 40 | 400 ± 40 | 400 ± 40 | 340 ± 40 | 380 ± 40 |

| ΔH, kJ/mole | 200 ± 20 | 200 ± 20 | 1030 ± 100 | 970 ± 100 | 500 ± 50 | 300 ± 30 |

| Low ionic strength conditions (no KCl) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Domain I (transition 1) | Domain II (transition 2) | Domain II (transition 3) | |||

| S1(A1) | S1(A2) | S1(A1) | S1(A2) | S1(A1) | S1(A2) | |

| T*, K | 319.2 ± 0.4 | 321.4 ± 0.4 | 323.0 ± 0.4 | 323.0 ± 0.4 | 325.5 ± 0.4 | 325.6 ± 0.4 |

| Ea, kJ/mole | 230 ± 40 | 250 ± 40 | 350 ± 40 | 400 ± 40 | 390 ± 40 | 390 ± 40 |

| ΔH, kJ/mole | 370 ± 40 | 380 ± 40 | 1260 ± 130 | 720 ± 70 | 400 ± 40 | 260 ± 30 |

© 2010 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Markov, D.I.; Zubov, E.O.; Nikolaeva, O.P.; Kurganov, B.I.; Levitsky, D.I. Thermal Denaturation and Aggregation of Myosin Subfragment 1 Isoforms with Different Essential Light Chains. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 4194-4226. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11114194

Markov DI, Zubov EO, Nikolaeva OP, Kurganov BI, Levitsky DI. Thermal Denaturation and Aggregation of Myosin Subfragment 1 Isoforms with Different Essential Light Chains. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2010; 11(11):4194-4226. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11114194

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarkov, Denis I., Eugene O. Zubov, Olga P. Nikolaeva, Boris I. Kurganov, and Dmitrii I. Levitsky. 2010. "Thermal Denaturation and Aggregation of Myosin Subfragment 1 Isoforms with Different Essential Light Chains" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 11, no. 11: 4194-4226. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11114194