Engineering Cofactor Preference of Ketone Reducing Biocatalysts: A Mutagenesis Study on a γ-Diketone Reductase from the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Serving as an Example

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Homology Modeling of Gre2p

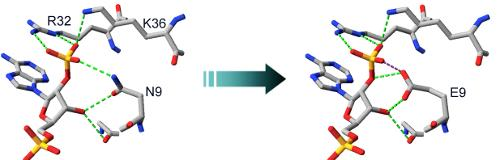

2.2. Structural Basis of Cofactor Specificity in Gre2p

2.3. Design and Experimental Evaluation of Mutants

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Chemicals

3.1.1. Strains and Growth Conditions

3.1.2. Molecular Biology Techniques/Construction of Plasmids

3.2. Homology Modeling

3.2.1. Enzyme Assays

3.2.2. Disintegration of E. coli Cells

3.2.3. Kinetic Characterization

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Bhowmick, K; Joshi, N. Syntheses and applications of C2-symmetric chiral diols. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2006, 17, 1901–1929. [Google Scholar]

- Bode, S; Wolberg, M; Müller, M. Stereoselective synthesis of 1,3-diols. Synthesis 2006, 4, 557–588. [Google Scholar]

- Burk, MJ. Modular phospholane ligands in asymmetric catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res 2000, 33, 363–372. [Google Scholar]

- Burk, MJ; Feaster, JE; Harlow, RL. New chiral phospholanes; synthesis, characterization, and use in asymmetric hydrogenation reactions. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1991, 2, 569–592. [Google Scholar]

- Burk, M; Ramsden, J. Modular, chiral P-heterocycles in asymmetric catalysis. In Handbook of Chiral Chemicals; Ager, D, Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 249–268. [Google Scholar]

- Short, RP; Kennedy, RM; Masamune, S. An improved synthesis of (-)-(2R,5R)-2,5-dimethylpyrrolidine. J. Org. Chem 1989, 54, 1755–1756. [Google Scholar]

- Díez, E; Fernández, R; Marqués-López, E; Martín-Zamora, E; Lassaletta, JM. Asymmetric synthesis of trans-3-amino-4-alkylazetidin-2-ones from chiral N,N-dialkylhydrazones. Org. Lett 2004, 6, 2749–2752. [Google Scholar]

- Cowart, M; Pratt, J; Stewart, A; Bennani, Y; Esbenshade, T; Hancock, A. A new class of potent non-imidazole H3 antagonists: 2-aminoethylbenzofurans. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2004, 14, 689–693. [Google Scholar]

- Depré, D; Chen, LY; Ghosez, L. A short multigram asymmetric synthesis of prostanoid scaffolds. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 6797–6812. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, QH; Yeung, CH; Chan, ASC. An improved synthesis of chiral diols via the asymmetric catalytic hydrogenation of prochiral diones. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1997, 8, 4041–4045. [Google Scholar]

- Solladie, G; Huser, N; Garcia-Ruano, JL; Adrio, J; Carreno, MC; Tito, A. Asymmetric synthesis of both enantiomers of 2.5-hexane diol and 2.6- heptane diol induced by chiral sulfoxides. Tetrahedron Lett 1994, 35, 5297–5300. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, J; Berenguer, R; Garcia, J; Loscertales, T; Manzanal, J; Vilarrasa, J. Stereoselective reduction of unsaturated 1,4-diketones. A practical route to chiral 1,4-diols. Tetrahedron Lett 1997, 38, 1091–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Mattson, A; Ohrner, N; Hult, K; Norin, T. Resolution of diols with C2-symmetry by lipase catalysed transesterification. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1993, 4, 925–930. [Google Scholar]

- Nagai, H; Morimoto, T; Achiwa, K. Facile enzymatic synthesis of optically active 2,5-hexanediol derivatives and its application to the preparation of optically pure cyclic sulfate for chiral ligands. Synlett 1994, 4, 289–290. [Google Scholar]

- Trost, BM. Atom economy - A challenge for organic synthesis: Homogeneous catalysis leads the way. Angew. Chem. Int. Edt 1995, 34, 259–281. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, R; van Rantwijk, F. Biocatalysis for sustainable organic synthesis. Aust. J. Chem 2004, 57, 281–289. [Google Scholar]

- Alcalde, M; Ferrer, M; Plou, F; Ballesteros, A. Environmental biocatalysis: from remediation with enzymes to novel green processes. Trends Biotechnol 2006, 24, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Lieser, JK. A simple synthesis of (S,S)-2,5-hexanediol. Synth. Commun 1983, 13, 765–767. [Google Scholar]

- Daussmann, T; Hennemann, HG; Rosen, TC; Dünkelmann, P. Enzymatic technologies for the synthesis of chiral alcohol derivatives. Chem. Ing. Technol 2006, 78, 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, K; Edegger, K; Kroutil, W; Liese, A. Overcoming the thermodynamic limitation in asymmetric hydrogen transfer reactions catalyzed by whole cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2006, 95, 192–198. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, M; Katzberg, M; Bertau, M; Hummel, W. Highly efficient and stereoselective biosynthesis of (2S,5S)-hexanediol with a dehydrogenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Org. Biomol. Chem 2010, 8, 1540–1550. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, S; Mitsuhashi, S; Kumobayashi, H. Process for producing optically active gamma-hydroxyketones. . European Patent EP 0592881B1, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Katzberg, M; Wechler, K; Müller, M; Dunkelmann, P; Stohrer, J; Hummel, W; Bertau, M. Biocatalytical production of (5S)-hydroxy-2-hexanone. Org. Biomol. Chem 2009, 7, 304–314. [Google Scholar]

- Edegger, K; Mang, H; Faber, K; Gross, J; Kroutil, W. Biocatalytic oxidation of sec-alcohols via hydrogen transfer. J. Mol. Catal. A 2006, 251, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ema, T; Moriya, H; Kofukuda, T; Ishida, T; Maehara, K; Utaka, M; Sakai, T. High enantioselectivity and broad substrate specificity of a carbonyl reductase: Towards a versatile biocatalyst. J. Org. Chem 2001, 66, 8682–8684. [Google Scholar]

- Ema, T; Yagasaki, H; Okita, N; Nishikawa, K; Korenaga, T; Sakai, T. Asymmetric reduction of a variety of ketones with a recombinant carbonyl reductase: Identification of the gene encoding a versatile biocatalyst. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2005, 16, 1075–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Kaluzna, I; Andrew, AA; Bonilla, M; Martzen, MR; Stewart, JD. Enantioselective reductions of ethyl 2-oxo-4-phenylbutyrate by Saccharomyces cerevisiae dehydrogenases. J. Mol. Catal. B 2002, 17, 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, M; Hahn-Hägerdal, B; Gorwa-Grauslund, MF. Screening of two complementary collections of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to identify enzymes involved in stereo-selective reductions of specific carbonyl compounds: An alternative to protein purification. Enzyme Microb. Technol 2003, 33, 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Kaluzna, IA; Matsuda, T; Sewell, AK; Stewart, JD. Systematic investigation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae enzymes catalyzing carbonyl reductions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 12827–12832. [Google Scholar]

- Johanson, T; Katz, M; Gorwa-Grauslund, MF. Strain engineering for stereoselective bioreduction of dicarbonyl compounds by yeast reductases. FEMS Yeast Res 2005, 5, 513–525. [Google Scholar]

- Kaluzna, IA; Feske, BD; Wittayanan, W; Ghiviriga, I; Stewart, JD. Stereoselective, biocatalytic reductions of α-Chloro-β-keto esters. J. Org. Chem 2005, 70, 342–345. [Google Scholar]

- Ema, T; Yagasaki, H; Okita, N; Takeda, M; Sakai, T. Asymmetric reduction of ketones using recombinant E. coli cells that produce a versatile carbonyl reductase with high enantioselectivity and broad substrate specificity. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 6143–6149. [Google Scholar]

- Warringer, J; Blomberg, A. Involvement of yeast YOL151W/GRE2 in ergosterol metabolism. Yeast 2006, 23, 389–398. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, M; Horn, P; Tournu, H; Hauser, NC; Hoheisel, JD; Brown, AJP; Dickinson, JR. A transcriptome analysis of isoamyl alcohol-induced filamentation in yeast reveals a novel role for Gre2p as isovaleraldehyde reductase. FEMS Yeast Res 2007, 7, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, CN; Porubleva, L; Shearer, G; Svrakic, M; Holden, LG; Dover, JL; Johnston, M; Chitnis, PR; Kohl, DH. Associating protein activities with their genes: rapid identification of a gene encoding a methylglyoxal reductase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 2003, 20, 545–554. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J; Wu, L; Knight, J. Stability of NADPH: Effect of various factors on the kinetics of degradation. Clin. Chem 1986, 32, 314–319. [Google Scholar]

- Andreadeli, A; Platis, D; Tishkov, V; Popov, V; Labrou, NE. Structure-guided alteration of coenzyme specificity of formate dehydrogenase by saturation mutagenesis to enable efficient utilization of NADP+. FEBS J 2008, 275, 3859–3869. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, YW; Pineau, I; Chang, HJ; Azzi, A; Bellemare, V; Laberge, S; Lin, SX. Critical residues for the specificity of cofactors and substrates in human estrogenic 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1: Variants designed from the three-dimensional structure of the enzyme. Mol. Endocrinol 2001, 15, 2010–2020. [Google Scholar]

- Serov, AE; Popova, AS; Fedorchuk, VV; Tishkov, VI. Engineering of coenzyme specificity of formate dehydrogenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. J 2002, 367, 841–847. [Google Scholar]

- Steen, I; Lien, T; Madsen, M; Birkeland, NK. Identification of cofactor discrimination sites in NAD-isocitrate dehydrogenase from Pyrococcus furiosus. Arch. Microbiol 2002, 178, 297–300. [Google Scholar]

- Kristan, K; Stojan, J; Moller, G; Adamski, J; Rizner, TL. Coenzyme specificity in fungal 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 2005, 241, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Rosell, A; Valencia, E; Ochoa, WF; Fita, I; Pares, X; Farres, J. Complete reversal of coenzyme specificity by concerted mutation of three consecutive residues in alcohol dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem 2003, 278, 40573–40580. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensberger, AH; Elling, RA; Wilson, DK. Structure-guided engineering of xylitol dehydrogenase cosubstrate specificity. Structure 2006, 14, 567–575. [Google Scholar]

- Bubner, P; Klimacek, M; Nidetzky, B. Structure-guided engineering of the coenzyme specificity of Pseudomonas fluorescens mannitol 2-dehydrogenase to enable efficient utilization of NAD(H) and NADP(H). Febs Lett 2008, 582, 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Jörnvall, H; Persson, B; Krook, M; Atrian, S; Gonzàlez-Duarte, R; Jeffery, J; Ghosh, D. Short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDR). Biochemistry 1995, 34, 6003–6013. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, JD; Rodriguez, S; Kayser, MM. Cloning, structure and activity of ketone reductases from baker’s yeast. In Enzyme Technologies for Pharmaceutical and Biotechnological Applications; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ; Chapter 7, pp. 175–207. [Google Scholar]

- Schlieben, NH; Niefind, K; Müller, J; Riebel, B; Hummel, W; Schomburg, D. Atomic resolution structures of R-specific alcohol dehydrogenase from Lactobacillus brevis provide the structural bases of its substrate and cosubstrate specificity. J. Mol. Biol 2005, 349, 801–813. [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi, M; Matsuura, K; Kaibe, H; Tanaka, N; Nonaka, T; Mitsui, Y; Hara, A. Switch of coenzyme specificity of mouse lung carbonyl reductase by substitution of threonine 38 with aspartic acid. J. Biol. Chem 1997, 272, 2218–2222. [Google Scholar]

- Duax, WL; Pletnev, V; Addlagatta, A; Bruenn, J; Weeks, CM. Rational proteomics I. Fingerprint identification and cofactor specificity in the short-chain oxidoreductase (SCOR) enzyme family. Proteins 2003, 53, 931–943. [Google Scholar]

- Otten, LG; Hollmann, F; Arends, IW. Enzyme engineering for enantioselectivity: From trial-and-error to rational design? Trends Biotechnol 2010, 28, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rost, B. Twilight zone of protein sequence alignments. Protein Eng. Design Select 1999, 12, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chothia, C; Lesk, AM. The relation between the divergence of sequence and structure in proteins. EMBO J 1986, 5, 823–826. [Google Scholar]

- Wallner, B; Elofsson, A. Identification of correct regions in protein models using structural, alignment, and consensus information. Protein Sci 2006, 15, 900–913. [Google Scholar]

- Benkert, P; Tosatto, SCE; Schomburg, D. QMEAN: A comprehensive scoring function for model quality assessment. Proteins 2008, 71, 261–277. [Google Scholar]

- Rossmann, MG; Moras, D; Olsen, KW. Chemical and biological evolution of a nucleotide-binding protein. Nature 1974, 250, 194–199. [Google Scholar]

- Kallberg, Y; Oppermann, U; Jornvall, H; Persson, B. Short-chain dehydrogenase. Protein Sci 2002, 11, 636–641. [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh, K; Jornvall, H; Persson, B; Oppermann, U. The SDR superfamily: functional and structural diversity within a family of metabolic and regulatory enzymes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 2008, 65, 3895–3906. [Google Scholar]

- Kamitori, S; Iguchi, A; Ohtaki, A; Yamada, M; Kita, K. X-ray structures of NADPH-dependent carbonyl reductase from Sporobolomyces salmonicolor provide insights into stereoselective reductions of carbonyl compounds. J. Mol. Biol 2005, 352, 551–558. [Google Scholar]

- Jörnvall, H; Persson, M; Jeffery, J. Alcohol and polyol dehydrogenases are both divided into two protein types, and structural properties cross-relate the different enzyme activities within each type. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 4226–4230. [Google Scholar]

- Geissler, R; Brandt, W; Ziegler, J. Molecular modeling and site-directed mutagenesis reveal the benzylisoquinoline binding site of the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase salutaridine reductase. Plant Physiol 2007, 143, 1493–1503. [Google Scholar]

- McKeever, BM; Hawkins, BK; Geissler, WM; Wu, L; Sheridan, RP; Mosley, RT; Andersson, S. Amino acid substitution of arginine 80 in 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 3 and its effect on NADPH cofactor binding and oxidation/reduction kinetics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1601, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, PB; Golovin, A. Cation-Pi interactions in protein-protein interfaces. Proteins 2005, 59, 231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi, M; Kaibe, H; Matsuura, K; Kakumoto, M; Tanaka, N; Nonaka, T; Mitsui, Y; Hara, A. Site-directed mutagenesis of residues in coenzyme-binding domain and active site of mouse lung carbonyl reductase. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 1997, 414, 555–561. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, D; Sawicki, M; Pletnev, V; Erman, M; Ohno, S; Nakajin, S; Duax, WL. Porcine carbonyl reductase - Structural basis for a functional monomer in short chain dehydrogenases/reductases. J. Biol. Chem 2001, 276, 18457–18463. [Google Scholar]

- Schormann, N; Karpova, E; Zhou, J; Zhang, Y; Symersky, J; Bunzel, R; Huang, WY; Arabshahi, A; Qiu, S; Luan, CH; Gray, R; Carson, M; Tsao, J; Luo, M; Johnson, D; Lu, S; Lin, G; Luo, D; Cao, Z; Li, S; McKinstry, A; Shang, Q; Chen, YJ; Bray, T; Nagy, L; DeLucas, L. Crystal Structure of putative Tropinone Reductase-II from Caenorhabditis Elegans with Cofactor and Substrate. Protein Data Bank 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Petit, P; Granier, T; d’Estaintot, BL; Manigand, C; Bathany, K; Schmitter, JM; Lauvergeat, V; Hamdi, S; Gallois, B. Crystal Structure of Grape Dihydroflavonol 4-Reductase, a Key Enzyme in Flavonoid Biosynthesis. J. Mol. Biol 2007, 368, 1345–1357. [Google Scholar]

- Luetz, S; Giver, L; Lalonde, J. Engineered enzymes for chemical production. Biotech. Bioeng 2008, 101, 647–653. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J; Fritsch, EF; Maniatis, T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Friberg, A; Johanson, T; Franzen, J; Gorwa-Grauslund, MF; Frejd, T. Efficient bioreduction of bicyclo[2.2.2]octane-2,5-dione and bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-7-ene-2,5-dione by genetically engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Org. Biomol. Chem 2006, 4, 2304–2312. [Google Scholar]

- Larkin, MA; Blackshields, G; Brown, NP; Chenna, R; McGettigan, PA; McWilliam, H; Valentin, F; Wallace, IM; Wilm, A; Lopez, R; Thompson, JD; Gibson, TJ; Higgins, DG. Clustal W and clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2947–2948. [Google Scholar]

- Guex, N; Peitsch, MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 1997, 18, 2714–2723. [Google Scholar]

- Sippl, MJ. Calculation of Conformational Ensembles from Potentials of Mean Force - an Approach to the Knowledge-Based Prediction of Local Structures in Globular-Proteins. J. Mol. Biol 1990, 213, 859–883. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, K; Bordoli, L; Kopp, J; Schwede, T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: A web-based environment for protein structure homology modeling. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Schormann, N; Zhou, J; Karpova, E; Zhang, Y; Symersky, J; Bunzel, B; Huang, WY; Arabshahi, A; Qiu, S; Luan, CH; Gray, R; Carson, M; Tsao, J; Luo, M; Johnson, D; Lu, S; Lin, G; Luo, D; Cao, Z; Li, S; McKinstry, A; Shang, Q; Chen, YJ; Bray, T; Nagy, L; DeLucas, L. Crystal structure of short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase of unknown function from Caenorhabditis elegans with Cofactor. Protein Data Bank 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, D; Wawrzak, Z; Weeks, CM; Duax, WL; Erman, M. The refined three-dimensional structure of 3α,20β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and possible roles of the residues conserved in short-chain dehydrogenases. Structure 1994, 2, 629–640. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, N; Nonaka, T; Tanabe, T; Yoshimoto, T; Tsuru, D; Mitsui, Y. Crystal structures of the binary and ternary complexes of 7-alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 7715–7730. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, A; Endo, M; Higashi, T; Nakatsu, T; Yamada, Y; Oda, J; Kato, H. Capturing enzyme structure prior to reaction initiation: Tropinone reductase-II-substrate complexes. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 5566–5573. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, C; Maser, E; Mobus, E; Klebe, G; Reuter, K; Ficner, R. The crystal structure of 3 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/carbonyl reductase from Comamonas testosteroni shows a novel oligomerization pattern within the short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family. J. Biol. Chem 2000, 275, 41333–41339. [Google Scholar]

- Lukacik, P; Kavanagh, KL; Oppermann, U. Structure and function of human 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 2006, 248, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Pilka, E; Guo, K; Kavanagh, K; Von Delft, F; Arrowsmith, C; Weigelt, J; Edwards, A; Sundstrom, M; Oppermann, U. Crystal structure of 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase type1, complexed with NAD+. Protein Data Bank 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Benach, J; Atrian, S; Gonzàlez-Duarte, R; Ladenstein, R. The catalytic reaction and inhibition mechanism of Drosophila alcohol dehydrogenase: Observation of an enzyme-bound NAD-ketone adduct at 1.4 Å resolution by X-ray crystallography. J. Mol. Biol 1999, 289, 335–355. [Google Scholar]

| Abbreviation | Name/putative function of the protein | Source organism | NCBI GenBank Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zroux | AF178079_1 dehydrogenase | Zygosaccharomyces rouxii | AAF22287.1 |

| Pstip | GRE2 methylglyoxal reductase | Pichia stipitis CBS 6054 | XP_001384081 |

| Dhans | DEHA2A06314p hypothetical protein | Debaryomyces hansenii | CAG84554.2 |

| Pguil | PGUG_03246 hypothetical protein | Pichia guilliermondii ATCC 6260 | XP_001485517.1 |

| Lelon | hypothetical protein | Lodderomyces elongisporus NRRL YB-4239 | XP_001527072.1 |

| Cglab | hypothetical protein | Candida glabrata | XP_445918.1 |

| GRE2 | Yol151wp / 3-methyl butanal reductase | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | NP_014490 |

| Calbi | oxidoreductase | Candida albicans SC5314 | XP_719286 |

| Lthrm | KLTH0F04026p | Lachancea thermotolerans CBS6340 | XP_002554383 |

| Ygl39 | dehydrogenase YGL039w | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | NP_011476.1 |

| Cglob | CHGG_00287 hypothetical protein | Chaetomium globosum CBS 148.51 | XP_001219508.1 |

| Ylipo | YALI0D07062p | Yarrowia lipolytica | XP_502514 |

| Vpoly | hypothetical protein | Vanderwaltozyma polyspora DSM 70294 | XP_001642950.1 |

| Pmarn | ketoreductase | Penicillium marneffei ATCC 18224 | XP_002151938 |

| Aclav | ketoreductase | Aspergillus clavatus NRRL 1 | XP_001275327 |

| Nfish | ketoreductase | Neosartorya fischeri NRRL 181 | XP_001260510 |

| Aderm | ketoreductase | Ajellomyces dermatitidis SLH14081 | XP_002625096 |

| Ptrit | dihydroflavonol-4-reductase | Pyrenophora tritici-repentis Pt-1C-BFP | XP_001938846 |

| Aflav | aldehyd reductase II | Aspergillus flavus NRRL3357 | EED56897.1 |

| Aoryz | RIB40 hypothetical protein | Aspergillus oryzae | XP_001817435.1 |

| SSCR | carbonyl reductase | Sporobolomyces salmonicolor | AAF15999 |

| Acaps | aldehyd reductase | Ajellomyces capsulatus G186AR | EEH09765.1 |

| Bfckl | BC1G_06734 hypothetical protein | Botryotinia fuckeliana B05.10 | XP_001554946.1 |

| Ssclr | SS1G_13307 hypothetical protein | Sclerotinia sclerotiorum 1980 | XP_001585790.1 |

| Gzeae | FG11217.1 hypothetical protein | Gibberella zeae PH-1 | XP_391393.1 |

| PDB-Code | Name of the protein | Source organism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1XKQ | short-chain dehydrogenase / reductase with unknown function | Caenorhabditis elegans | [74] |

| 1XHL | tropinone reductase II | Caenorhabditis elegans | [65] |

| 2HSD | 3α,20β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase | Streptomyces exfoliates | [75] |

| 1AHH | 7 α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase | Escherichia coli | [76] |

| 1IPE | tropinone reductase II | Datura stramonium | [77] |

| 1FK8 | 3α-ydroxysteroid dehydrogenase | Comamonas testosteroni | [78] |

| 1ZBQ | 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 4 | Homo sapiens | [79] |

| 2GDZ | 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase type1 | Homo sapiens | [80] |

| 1B14 | alcohol dehydrogenase | Drosophila lebanonensis | [81] |

| 1N5D | carbonyl reductase | Sus scrofa | [64] |

| Gre2p wt | Gre2p N9E | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NADPH | NADH | NADPH | NADH | |

| KM cin mM | 0.038 | 1.45 | 1.52 | 0.96 |

| vmax a,cin U/g (protein) | 288 | 81 | 272 | 147 |

| Cofactor preference b | 136 | 0,007 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| Namea | Sequenceb |

|---|---|

| GRE2N_F (PstI)c | 5′–AACTGCAGAACAGATAGCAGTATCACACGCCCGTAAAT–3′ |

| GRE2N_R (HindIII)c | 5′–AAAAGCTTGAAGAGAAAAATGCGCAGAGATGTACTAGATGAT–3′ |

| R32E_F | 5′–GGTCATCGGTTCTGCCGAAAGTCAAGAAAAGGCCGAGAATTTAACGG–3′ |

| R32D_F | 5′–GGTCATCGGTTCTGCCGACAGTCAAGAAAAGGCCGAGAATTTAACGG–3′ |

| R32G_F (BamHI) | 5′–GGTCATCGGTTCTGCCGGATCCCAAGAAAAGGCCGAGAATTTAACGG–3′ |

| R32L_F | 5′–GGTCATCGGTTCTGCTTTAAGTCAAGAAAAGGCCGAGAATTTAACGC–3′ |

| A31E_F | 5′–GAAGACTATAAGGTCATCGGTTCTGAGAGAAGTCAAGAAAAGGCC–3′ |

| A31D_F (BstYI) | 5′–GAAGACTATAAGGTCATCGGATCTGATAGAAGTCAAGAAAAGGCC–3′ |

| N9D_F (BsgI) | 5′–CAGTTTTTGTTTCAGGTGCAGACGGGTTCATTGCCCAAC–3′ |

| N9E_F | 5′–CAGTTTTTGTTTCAGGTGCTGAGGGGTTCATTGCCCAAC–3′ |

© 2010 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Katzberg, M.; Skorupa-Parachin, N.; Gorwa-Grauslund, M.-F.; Bertau, M. Engineering Cofactor Preference of Ketone Reducing Biocatalysts: A Mutagenesis Study on a γ-Diketone Reductase from the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Serving as an Example. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 1735-1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11041735

Katzberg M, Skorupa-Parachin N, Gorwa-Grauslund M-F, Bertau M. Engineering Cofactor Preference of Ketone Reducing Biocatalysts: A Mutagenesis Study on a γ-Diketone Reductase from the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Serving as an Example. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2010; 11(4):1735-1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11041735

Chicago/Turabian StyleKatzberg, Michael, Nàdia Skorupa-Parachin, Marie-Françoise Gorwa-Grauslund, and Martin Bertau. 2010. "Engineering Cofactor Preference of Ketone Reducing Biocatalysts: A Mutagenesis Study on a γ-Diketone Reductase from the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Serving as an Example" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 11, no. 4: 1735-1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11041735