Biofunctional Constituents from Liriodendron tulipifera with Antioxidants and Anti-Melanogenic Properties

Abstract

:1. Introduction

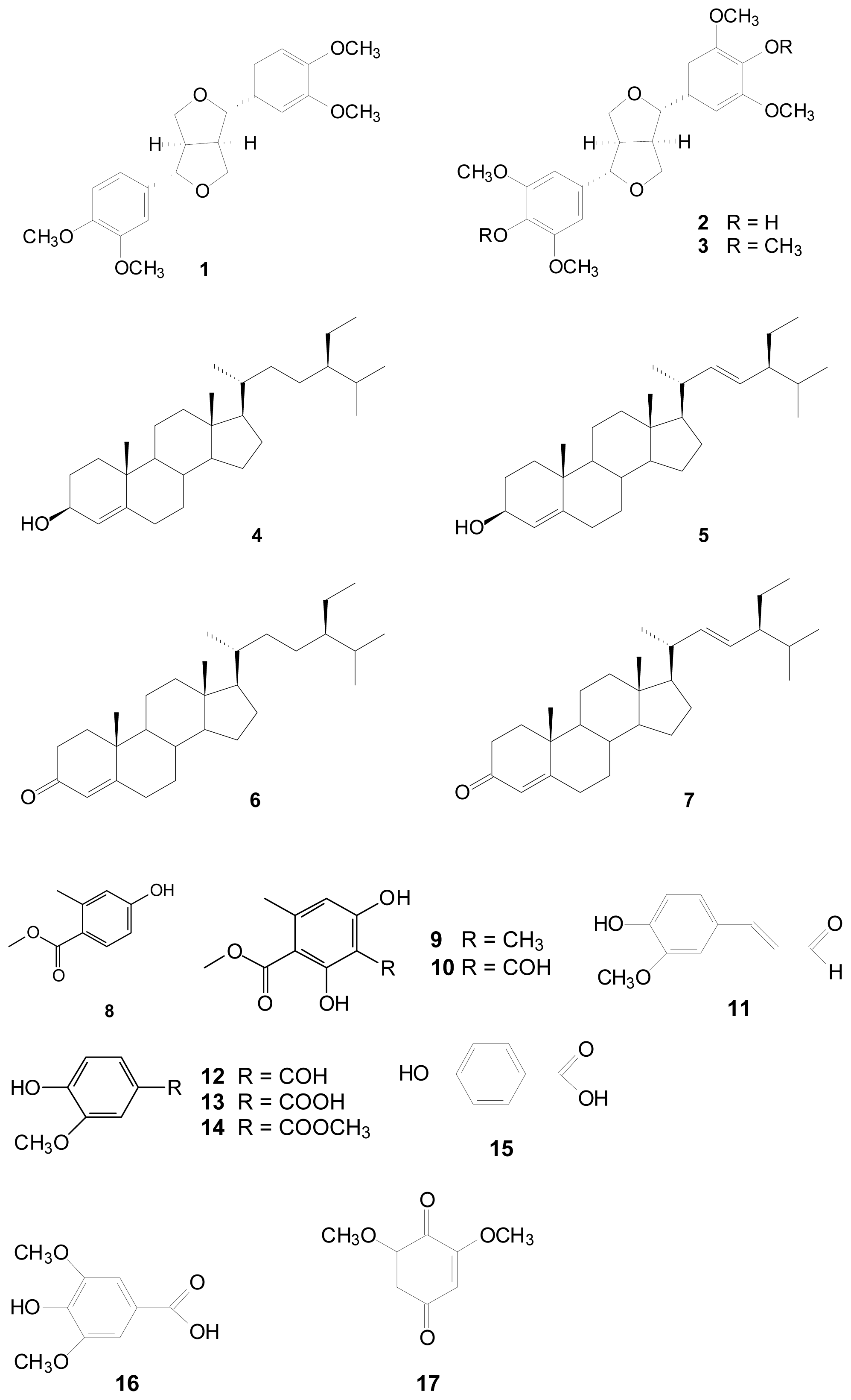

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Antioxidant Activities of Compounds 1 to 17 from Liriodendron tulipifera

2.1.1. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Activity Assay

2.1.2. ABTS+ Cation Radical Scavenging Assay

2.1.3. Ferrous Ions Chelating Capacity

2.1.4. FRAP Power

2.2. In vitro Mushroom Tyrosinase Inhibition

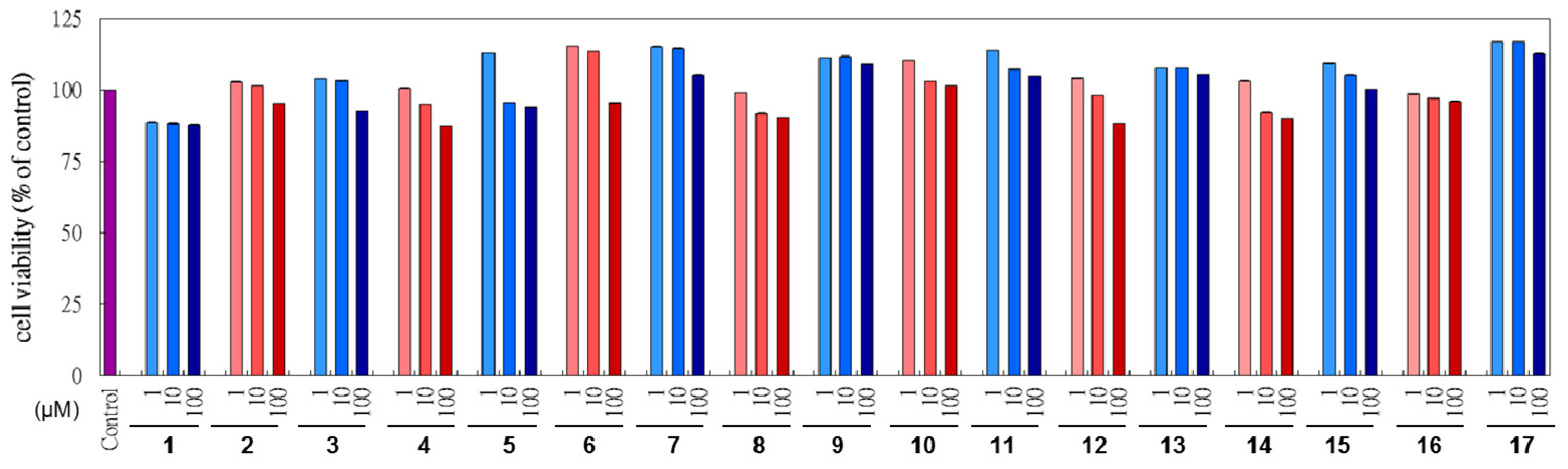

2.3. Cytotoxicity of L. tulipifera Compounds in B16F10 Cells

2.4. Cell Based Examination on L. tulipifera Compounds

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General Procedure

3.2. Plant Material

3.3. Extraction Isolation and Identification

3.4. Reagents and Materials

3.5. Determination of DPPH Radical Scavenging Capacity

3.6. ABTS+ Cation Radical Scavenging Assay

3.7. Metal Chelating Activity

3.8. Reducing Power

3.9. Assay on Mushroom Tyrosinase Activity

3.10. Cell Culture

3.11. Cell Viability

3.12. Melanin Quantification

3.13. Tyrosinase Assay

3.14. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Kim, T.W. The Woody Plants of Korea in Color; Kyo-Hak publishing Co., Ltd.: Seoul, Korea, 1995; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Merkle, S.A.; Sommer, H.E. Yellow-Poplar (Liriodendron spp.). In Biotechnology in Agriculture and Forestry, Trees III; Bajaj, Y.P.S., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1991; Volume 16, pp. 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, I.; Hufford, C.D. Phenylpropanoids, sesqiterpenes, and alkaloids from the seeds of Liriodendron tulipifera. J. Nat. Prod 1989, 52, 1177–1179. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.H.; Qin, G.W.; Li, X.Y.; Xu, R.S. New biflavanones and bioactive compounds from Stellera chamaejasme L. Yao Xue Xue Bao 2011, 36, 669–671. [Google Scholar]

- Kelm, M.A.; Nair, M.G. A brief summary of biologically active compounds from Magnolia spp. Nat. Prod. Chem 2000, 24, 845–873. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.Y.; Cheng, M.J.; Chiang, Y.J.; Bai, J.C.; Chiu, C.T.; Lin, R.J.; Hsui, Y.R.; Lo, W.L. Chemical constituents from the leaves of Machilus zuihoensis Hayata var. mushaensis (Lu) Y.C. Liu. Nat. Prod. Res 2009, 23, 871–875. [Google Scholar]

- Baldé, A.M.; Apers, S.; de Bruyne, T.E.; van den Heuvel, H.; Claeys, M.; Vlietinck, A.J.; Pieters, L.A. Steroids from Harrisonia abyssinica. Planta Med 2000, 66, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Piao, Y.Z.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, Y.A.; Lee, H.S.; Hammock, B.D.; Lee, Y.T. Development of ELISAs for the class-specific determination of organophosphorus pesticides. J. Agric. Food Chem 2009, 57, 10004–10013. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, I.S.; Lotina-Hennsen, B.; Mata, R. Effect of lichen metabolites on thylakoid electron transport and photophosphorylation in isolated spinach chloroplasts. J. Nat. Prod 2000, 63, 1396–1399. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, M.; Li, X. Antioxidant activity and chemical composition of Torreya grandis cv. Merrillii seed. Nat. Prod. Commun 2009, 4, 1565–1570. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.Y.; Chang, F.R.; Wu, Y.C. Cheritamine, a new N-Fatty acyl tryamine and other constituents from the stems of Annona cherimola. J. Chin. Chem. Soc 1999, 46, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.M.; Chou, Y.T.; Hong, Z.L.; Chen, H.A.; Chang, Y.C.; Yang, W.L.; Chang, H.C.; Mai, C.T.; Chen, C.Y. Bioconstituents from stems of Synsepalum dulcificum Daniell (Sapotaceae) inhibit human melanoma proliferation, reduce mushroom tyrosinase activity and have antioxidant properties. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng 2011, 42, 204–211. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.Y.; Cheng, K.C.; Chang, A.Y.; Lin, Y.T.; Hseu, Y.C.; Wang, H.M. 10-Shogaol, an antioxidant from Zingiber officinale for skin cell proliferation and migration enhancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2012, 13, 1762–1777. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.M.; Cheng, K.C.; Lin, C.J.; Hsu, S.W.; Fang, W.C.; Hsu, T.F.; Chiu, C.C.; Chang, H.W.; Hsu, C.H.; Lee, A.Y. Obtusilactone A and (−)-sesamin induce apoptosis in human lung cancer cells via inhibiting mitochondrial Lon protease and activating DNA damage checkpoints. Cancer Sci 2010, 101, 2612–2620. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.C.; Chou, H.I.; Wu, P.F.; Wang, H.M.; Chen, C.Y. Bio-functional constituents from the stems of Liriodendron tulipifera. Molecules 2012, 17, 4357–4372. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.M.; Pan, J.L.; Chiu, C.C.; Chen, C.Y.; Yang, M.H.; Chang, J.S. Identification of anti-lung cancer extract from Chlorella vulgaris C–C by antioxidant property using supercritical carbon dioxide extraction. Process Biochem 2010, 45, 1865–1872. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, W.T.; Huang, T.S.; Chiu, C.C.; Pan, J.L.; Liang, S.S.; Chen, B.H.; Chen, S.H.; Liu, P.L.; Wang, H.C.; Wang, H.M.; et al. Biological properties of acidic cosmetic water from seawater. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2012, 13, 5952–5971. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.Y.; Kuo, P.L.; Chen, Y.H.; Huang, J.C.; Ho, M.L.; Lin, R.J.; Chang, J.S.; Wang, H.M. Tyrosinase inhibition, free radical scavenging, antimicrobial and anticancer proliferation activities of Sapindus mukorossi extracts. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng 2010, 41, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.M.; Chen, C.Y.; Chen, H.A.; Huang, W.C.; Lin, W.R.; Chen, T.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Chien, H.J.; Lu, P.L.; Lin, C.M.; et al. Zingiber officinale (ginger) compounds with tetracycline have synergistic effects against clinical extensively-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Phytother. Res 2010, 24, 1825–1830. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.H.; Chang, H.W.; Huang, H.M.; Chong, I.W.; Chen, J.S.; Chen, C.Y.; Wang, H.M. (−)-Anonaine induces oxidative stress and DNA damage to inhibit growth and migration of human lung carcinoma H1299 cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 2284–2290. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.M.; Chen, C.Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Ho, M.L.; Chou, Y.T.; Chang, H.C.; Lee, C.H.; Wang, C.Z.; Chu, I.M. (−)-N-Formylanonaine from Michelia alba as a human tyrosinase inhibitor and antioxidant. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 5241–5247. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.M.; Chen, C.Y.; Wen, Z.H. Identifying melanogenesis inhibitors from Cinnamomum subavenium with in vitro and in vivo screening systems by targeting the human tyrosinase. Exp. Dermatol 2011, 20, 242–248. [Google Scholar]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved abts radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radical Biol. Med 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.M.; Chiu, C.C.; Wu, P.F.; Chen, C.Y. Subamolide E from Cinnamomum subavenium induces sub G1 cell cycle arrest, caspase-dependent apoptosis, and reduces migration ability of human melanoma cells. J. Agric. Food Chem 2011, 59, 8187–8192. [Google Scholar]

| Compounds | DPPH (%) | ABTS (%) | Chelating (%) | Reducing power (OD700) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C a | 88.6 ± 1.8 | 76.4 ± 5.6 | - | - |

| EDTA b | - | - | 86.9 ± 4.5 | - |

| BHA c | - | - | - | 0.98 ± 0.1 |

| (−)-Eudesmin (1) | ns | 64.1 ± 5.6 | ns | 0.28 ± 0.0 |

| (+)-Syringaresinol (2) | 38.5 ± 4.8 | 84.8 ± 7.3 | ns | 0.66 ± 0.3 |

| (+)-Yangambin (3) | ns | 28.1 ± 6.7 | 13.5 ± 0.6 | 0.24 ± 0.0 |

| β-Sitosterol (4) | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Stigmasterol (5) | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| β-Sitostenone (6) | ns | 52.4 ± 7.4 | ns | 0.29 ± 0.0 |

| Stigmastenone (7) | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Methyl 4-hydroxy-2-methylbenzoate (8) | ns | ns | 17.4 ± 9.1 | 0.18 ± 0.0 |

| β-Orcinol carboxylate (9) | ns | 79.8 ± 2.2 | ns | 0.45 ± 0.0 |

| Methyl haematommate (10) | ns | 72.5 ± 6.1 | 19.8 ± 8.3 | 0.28 ± 0.0 |

| Coniferyl aldehyde (11) | ns | ns | ns | 0.24 ± 0.0 |

| Vanillin (12) | ns | 19.4 ± 5.5 | ns | 0.24 ± 0.0 |

| Vanillic acid (13) | ns | 22.7 ± 5.2 | ns | 0.18 ± 0.0 |

| Methyl vanillate (14) | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| p-Hydroxybenzoic acid (15) | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Syringic acid (16) | ns | 49.4 ± 10.8 | ns | 0.25 ± 0.0 |

| 2,6-Dimethoxy-p-quinone (17) | ns | 31.5 ± 13.5 | 25.5 ± 6.8 | 0.29 ± 0.0 |

| L. tulipifera compounds | Mushroom tyrosinase inhibition (%) |

|---|---|

| Kojic acid a | 89.2 ± 0.1 |

| (−)-Eudesmin (1) | ns |

| (+)-Syringaresinol (2) | ns |

| (+)-Yangambin (3) | ns |

| β-Sitosterol (4) | ns |

| Stigmasterol (5) | ns |

| β-Sitostenone (6) | ns |

| Stigmastenone (7) | ns |

| Methyl 4-hydroxy-2-methylbenzoate (8) | 23.2 ± 0.4 |

| β-Orcinol carboxylate (9) | ns |

| Methyl haematommate (10) | ns |

| Coniferyl aldehyde (11) | ns |

| Vanillin (12) | ns |

| Vanillic acid (13) | 22.8 ± 0.4 |

| Methyl vanillate (14) | ns |

| p-Hydroxybenzoic acid (15) | 15.4 ± 0.4 |

| Syringic acid (16) | 10.6 ± 0.4 |

| 2,6-Dimethoxy-p-quinone (17) | ns |

© 2013 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, W.-J.; Lin, Y.-C.; Wu, P.-F.; Wen, Z.-H.; Liu, P.-L.; Chen, C.-Y.; Wang, H.-M. Biofunctional Constituents from Liriodendron tulipifera with Antioxidants and Anti-Melanogenic Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 1698-1712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14011698

Li W-J, Lin Y-C, Wu P-F, Wen Z-H, Liu P-L, Chen C-Y, Wang H-M. Biofunctional Constituents from Liriodendron tulipifera with Antioxidants and Anti-Melanogenic Properties. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013; 14(1):1698-1712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14011698

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Wei-Jen, Yi-Chieh Lin, Pei-Fang Wu, Zhi-Hong Wen, Po-Len Liu, Chung-Yi Chen, and Hui-Min Wang. 2013. "Biofunctional Constituents from Liriodendron tulipifera with Antioxidants and Anti-Melanogenic Properties" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 1: 1698-1712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14011698