Transcriptome Comparative Profiling of Barley eibi1 Mutant Reveals Pleiotropic Effects of HvABCG31 Gene on Cuticle Biogenesis and Stress Responsive Pathways

Abstract

:1. Introduction

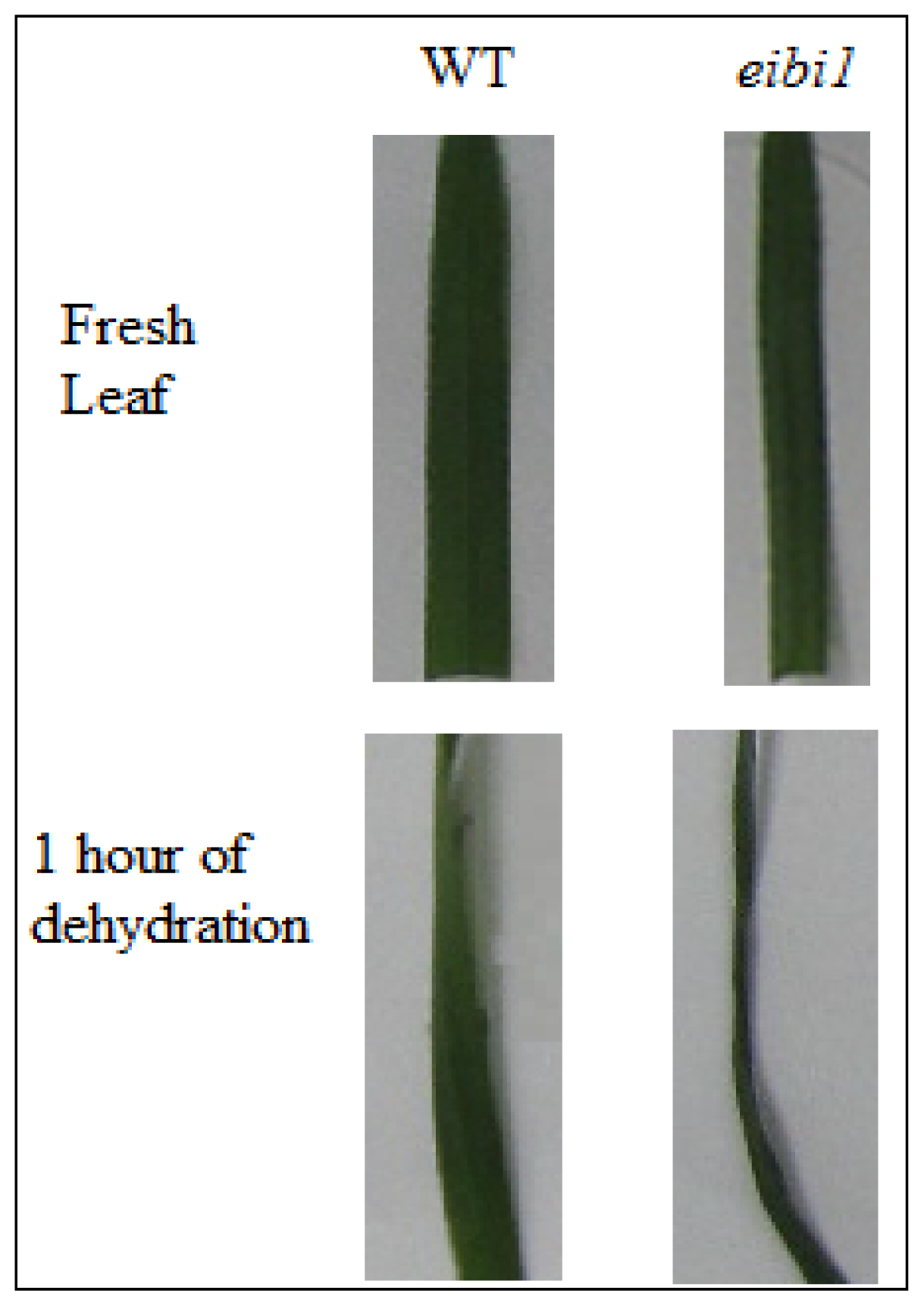

2. Results and Discussion

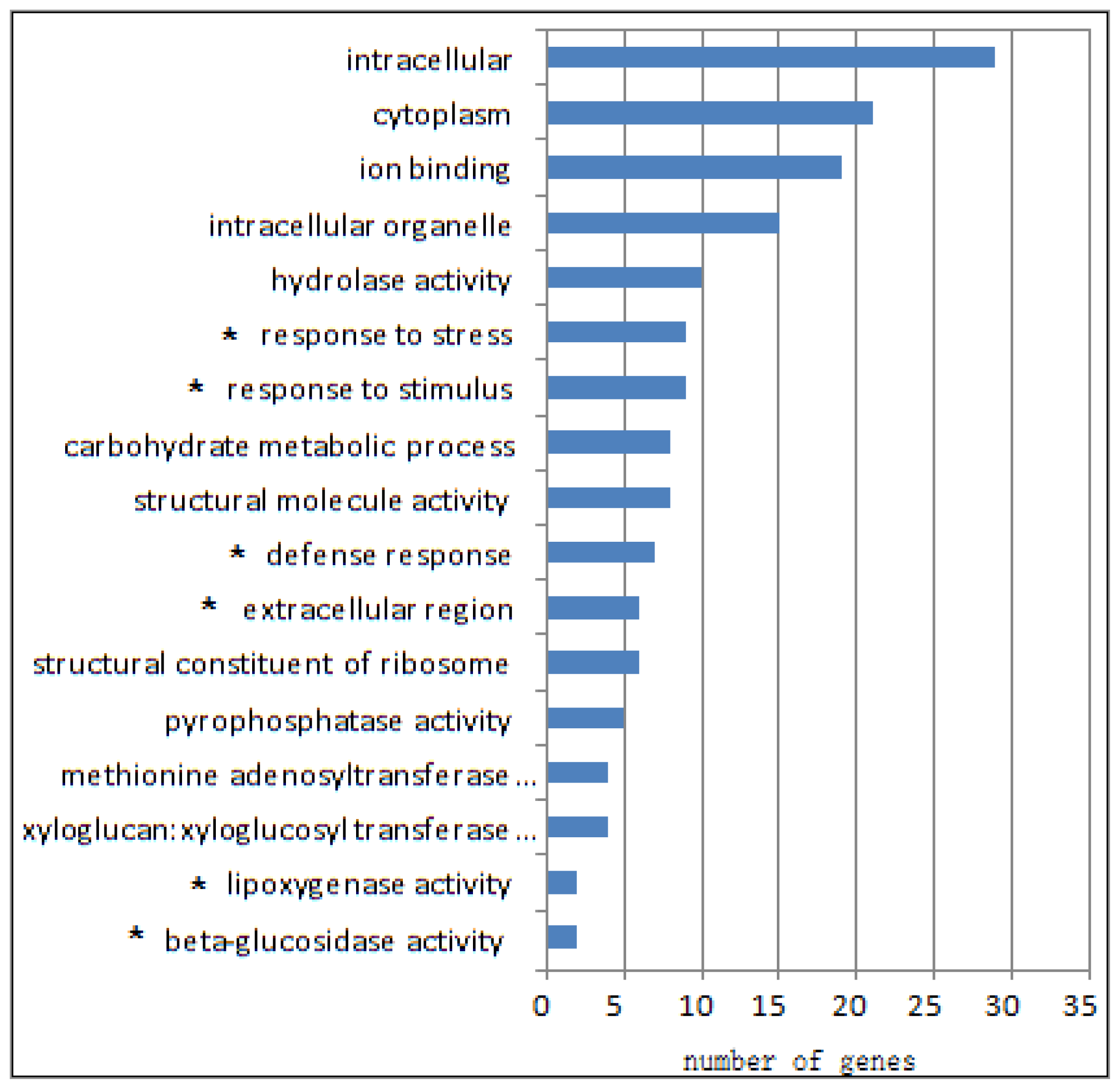

2.1. Differential Transcriptomes of eibi1 Compared with the Wild Type

2.2. Stress and Fatty Acid Metabolism Related Pathways Were Up-Regulated

2.3. The Metabolic Pathways Were Down-Regulated

2.4. The Epigenetic Related Pathways

2.5. Validation of Microarray Data by qRT-PCR

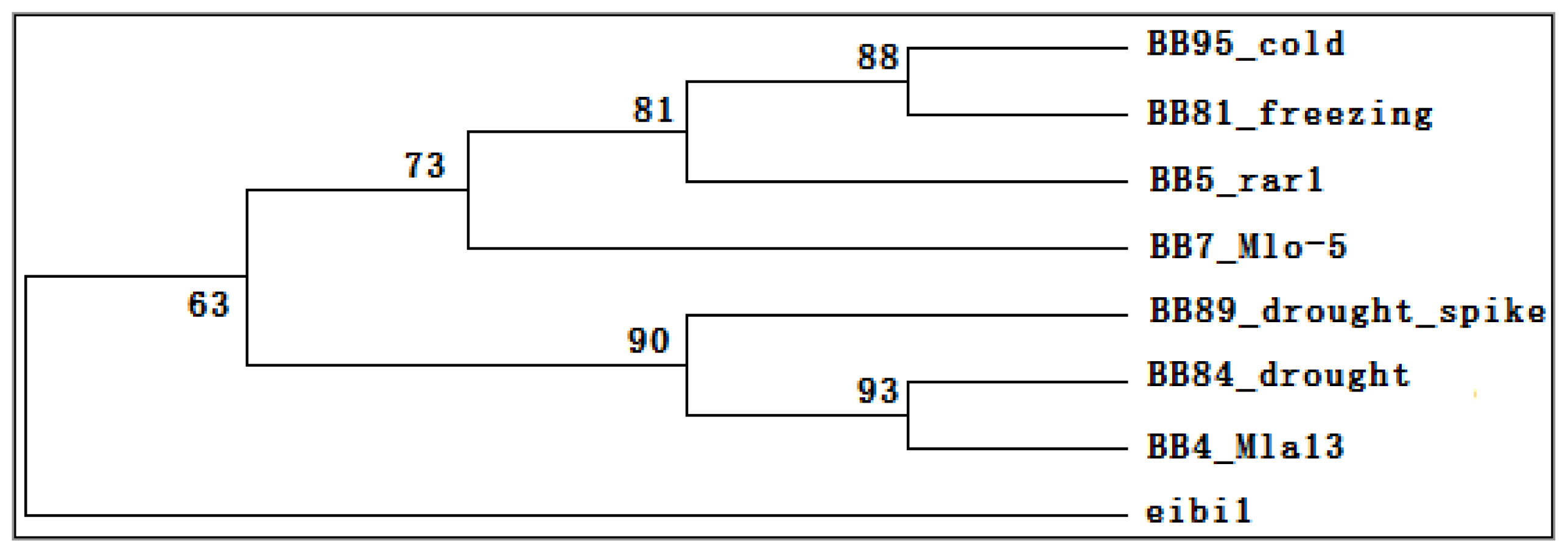

2.6. Transcriptomic Comparison of eibi1 with Other Barleys under Stresses

3. Experimental

3.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Design

3.2. Leaf Transcriptomic Microarray Analysis

3.3. Quantitative RT-PCR Validation of Eibi1 and Wild Type Gene Expression

3.4. Comparative Transcriptomic Analysis

4. Conclusions

| (Putative) gene function | Contig/gene designation | Regulation in eibi1/WT |

|---|---|---|

| Thionin | Contig1579_s_at | 39.5 |

| Contig1570_s_at | 18.5 | |

| Contig1582_x_at | 6.96 | |

| Contig1580_x_at | 4.07 | |

| Horcolin | Contig6157_s_at | 9.42 |

| Pathogen-related protein pir | Contig5607_s_at | 4.87 |

| Methyl jasmonate-inducible lipoxygenase 2 | Contig2305_at | 2.059 |

| Lipoxygenase | Contig23795_at | 3.729 |

| Metallophosphatase | Contig2289_at | 2.409 |

| carbonate dehydratase | Contig897_s_at | 2.363 |

| Chitinase | Contig2990_at | 5.87 |

| β-amylase | Contig1411_s_at | 5.03 |

| RNase S-like protein | contig5059_s_at | 2.212 |

| Lectin | contig11641_s_at | 2.099 |

| subtilisin-like protease | Contig13847_s_at | 3.188 |

| α-L-arabinofuranosidase/β-D-xylosidase | Contig7032_s_at | 2.842 |

| endo-1,3-β-glucanase | HVSMEm0003C15r2_s_at | 2.609 |

| glutathione synthetase | Contig14516_at | 2.379 |

| GDSL-motif lipase/hydrolase | Contig15_s_at | 6.113 |

| CYP450 | ||

| Contig 11818_at | 5.409 | |

| Contig 25477_at | 3.52 | |

| Contig3160_at | 3.235 | |

| Contig13847_at | 3.191 | |

| Contig14804_at | 2.308 | |

| Contig7194_at | 2.292 | |

| Contig14663_at | 2.111 | |

| ContigCEb0006F_at | 2.018 | |

| Fatty acid | Contig23795_at | 3.729 |

| Contig5664_at | 2.535 | |

| HVSMEn0002B08r2_at | 2.164 | |

| Contig2305_at | 2.059 |

| (Putative) gene function | Contig/gene designation | Regulation in eibi1/WT |

|---|---|---|

| ribophorin I | Contig4748_s_at | 0.499 |

| sucrose synthase 1 | Contig689_s_at | 0.499 |

| dTDP-glucose 4-6-dehydratase-like protein | Contig2918_s_at | 0.48 |

| UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase | Contig2915_at | 0.469 |

| UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase | Contig2031_s_at | 0.206 |

| ribosomal protein S8 | Contig1024_at | 0.467 |

| 60S | Contig2369_s_at | 0.43 |

| ribosomal protein L24 | HI02E24u_s_at | 0.331 |

| rpS28 | Contig3403_s_at | 0.321 |

| ribosomal protein L17.1, cytosolic | rbags1i23_s_at | 0.302 |

| Ribosomal protein S7 | Contig1668_at | 0.273 |

| peroxidase (EC 1.11.1.7), pathogen-induced | Contig2118_at | 0.325 |

| HSP80-2 | Contig1204_s_at | 0.433 |

| Endoxyloglucan transferase (EXT) | Contig5258_at | 0.423 |

| Serine carboxypeptidase III precursor (CP-MIII) | Contig682_s_at | 0.413 |

| glutathione peroxidase-like protein | Contig2453_at | 0.406 |

| Pyrophosphate phospho-hydrolase (PPase) | Contig2018_at | 0.389 |

| phenylalanine ammonia-lyase | Contig1805_s_at | 0.496 |

| phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (EC 4.3.1.5) | Contig1803_at | 0.37 |

| phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (EC 4.3.1.5 | HVSMEm0015M15r2_s_at | 0.366 |

| phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (EC 4.3.1.5) | Contig1800_at | 0.353 |

| Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Contig149_at | 0.361 |

| immunophilin | HVSMEg0002K18r2_s_at | 0.358 |

| ascorbate peroxidase | Contig1727_s_at | 0.242 |

| plasma membrane proton ATPase | Contig2_s_at | 0.296 |

| xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XET) | Contig2670_x_at | 0.3 |

| xyloglucan endo-1,4-β-D-glucanase(XET) | Contig2672_at | 0.335 |

| xyloglucan endo-1,4-β-D-glucanase | Contig2670_s_at | 0.358 |

| promoter-binding factor-like protein | Contig10705_at | 0.443 |

| Actin | Contig1390_M_at | 0.187 |

| serine carboxypeptidase III | Contig682_s_at | 0.413 |

| glutathione peroxidase-like protein GPX54Hv | Contig2453_at | 0.406 |

| (Putative) gene function | Contig/gene designation | Regulation in eibi1/WT |

|---|---|---|

| Methionine adenosyltransferase 1 | Contig1269_at | 0.456 |

| Methionine adenosyltransferase 1 | Contig1271_x_at | 0.427 |

| Methionine adenosyltransferase 1 | Contig1269_s_at | 0.327 |

| S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine hydrolase | Contig1791_x_at | 0.477 |

| S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine hydrolase | Contig1794_s_at | 0.271 |

| methionine synthase protein | Contig1424_at | 0.244 |

| putative histone deacetylase HD2 | Contig1625_at | 0.348 |

| Contig | Predict functional gene | EST accession | Primers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contig1579_s_at | Thionin | AK250720 | TGAATCTTCTCCCTGAATCCG CAAATAGATTCATCGTGGCGA |

| Contig6157_s_at | horcolin | AY033628 | CTACGTGACCGAAATCTCCG GCCATGTAAGGCACTTCACAA |

| Contig2990_at | chitinase | X78671 | CAACACCTTTCCGGGCTT CCGTCATCCAGAACCACATC |

| Contig 25477_at | CYP450 | AK252707 | CTTCCACAACGACCCTGACT AGCACCTGCACATCAAAGTTC |

| Contig23795_at | lipoxygenase | AJ507213 | TGATCCATCTGAAGCAGCCT TTGACGGTGAAGAAGGCG |

| Contig23796_at | Fatty acid | AJ507214 | CGCAGAGCAGCAATGTTG GCGACGGCAGGTATGACTT |

| Contig2031_s_at | UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase | AY677177 | TGAATCTTCTCCCTGAATCCG CAAATAGATTCATCGTGGCGA |

| Contig1269_s_at | Methionine adenosyltransferase 1 | AK249878 | CTACGTGACCGAAATCTCCG GCCATGTAAGGCACTTCACAA |

| Contig1794_s_at | S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine hydrolase | AM039898 | CAACACCTTTCCGGGCTT CCGTCATCCAGAACCACATC |

| Contig1424_at | methionine synthase protein | AM039905 | CTTCCACAACGACCCTGACT AGCACCTGCACATCAAAGTTC |

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, G.; Sagi, M.; Song, W.N.; Krugman, T.; Fahima, T.; Korol, A.B.; Nevo, E. Wild barley eibi1 mutation identifies a gene essential for leaf water conservation. Planta 2004, 219, 684–693. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Komatsuda, T.; Pourkheirandish, M.; Sameri, M.; Sato, K.; Krugman, T.; Fahima, T.; Korol, A.B.; Nevo, E. Mapping of the eibi1 gene responsible for the drought hypersensitive cuticle in wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum). Breed. Sci 2009, 59, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Komatsuda, T.; Pourkheirandish, M.; Sameri, M.; Sato, K.; Krugman, T.; Fahima, T.; Korol, A.B.; Nevo, E. Genetic targeting of candidate genes for drought sensitive gene eibi1 of wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum). Breed. Sci 2009, 59, 637–644. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Komatsuda, T.; Ma, J.F.; Nawrath, C.; Pourkheirandish, M.; Tagiri, A.; Hu, Y.G.; Sameri, M.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; et al. An ATP-binding cassette subfamily G full transporter is essential for the retention of leaf water in both wild barley and rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 12354–12359. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, J.L.; Cnudde, F.; Gerats, T. Forward genetics and map-based cloning approaches. Trends Plant Sci 2003, 8, 484–491. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, J.M.; Ecker, J.R. Moving forward in reverse, genetic technologies to enable genome-wide phenomic screens in Arabidopsis. Nat. Rev. Genet 2006, 7, 524–536. [Google Scholar]

- Close, T.J.; Wanamaker, S.I.; Caldo, R.A.; Turner, S.M.; Ashlock, D.A.; Dickerson, J.A.; Wing, R.A.; Muehlbauer, G.J.; Kleinhofs, A.; Wise, R.P. A new resource for cereal genomics, 22K Barley GeneChip comes of age. Plant Physiol 2004, 134, 960–968. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, R.M.; Gleason, C.A.; Edwards, A.; Hadfield, J.; Downie, J.A.; Oldroyd, G.E.D.; Long, S.R. A Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase required for symbiotic nodule development, Gene identification by transcript-based cloning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 4701–4705. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Fetch, T.; Nirmala, J.; Schmierer, D.; Brueggeman, R.; Steffenson, B.; Kleinhofs, A. Rpr1, a gene required for Rpg1-dependent resistance to stem rust in barley. Theor. Appl. Genet 2006, 113, 847–855. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, L.; Moscou, M.J.; Meng, Y.; Xu, W.; Caldo, R.A.; Shaver, M.; Nettleton, D.; Wise, R.P. Transcript-based cloning of RRP46, a regulator of rRNA processing and R gene-independent cell death in barley-powdery mildew interactions. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3280–3295. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Lavery, L.; Gill, U.; Gill, K.; Steffenson, B.; Yan, G.; Chen, X.; Kleinhofs, A. A cation/proton-exchanging protein is a candidate for the barley NecS1 gene controlling necrosis and enhanced defense response to stem rust. Theor. Appl. Genet 2009, 118, 385–397. [Google Scholar]

- Stec, B. Plant thionins—The structural perspective. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 2006, 63, 1370–1385. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald, I.; Heinig, I.; Thole, H.H.; Neumann, D.; Kahmann, U.; Kloppstech, K.; Gau, A.E. Purification and characterisation of a jacalin-related, coleoptile specific lectin from Hordeum vulgare. Planta 2007, 226, 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme, E.J.M.; Barre, A.; Rouge, P.; Peumans, W.J. Potato lectin, an updated model of a unique chimeric plant protein. Plant J 2004, 37, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.H.; Tian, B.; Lia, Y.L. Overexpression of a wheat jasmonate-regulated lectin increases pathogen resistance. Biochimie 2010, 92, 187–193. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, P.J.; Somssich, I.E. Transcriptional control of plant genes responsive to pathogens. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol 1998, 1, 311–315. [Google Scholar]

- Umate, P.; Tuteja, N. Genome-wide analysis of lipoxygenase gene family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Signal. Behav 2011, 6, 335–338. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, T.H.; Howe, K.J.; Matas, A.J.; Buda, G.J.; Thannhauser, T.W.; Rose, J.K.C. Mining the surface proteome of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruit for proteins associated with cuticle biogenesis. J. Exp. Bot 2010, 61, 3759–3771. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.E.; Nemacheck, J.A.; Shukle, J.T.; Subramanyam, S.; Saltzmann, K.D.; Shukle, R.H. Induced epidermal permeability modulates resistance and susceptibility of wheat seedlings to herbivory by Hessian fly larvae. J. Exp. Bot 2011, 62, 4521–4531. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, T.; Jin, S.; Yoshida, M.; Hoshino, T.; Opassiri, R.; Cairns, J.R.K. Expression of an endo-(1,3;1,4)-β-glucanase in response to wounding, methyl jasmonate, abscisic acid and ethephon in rice seedlings. J. Plant Physiol 2009, 166, 1814–1825. [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme, E.J.; Zhang, W.; Peumans, W.J. Induction of cytoplasmic mannose-binding jacalin-related lectins is a common phenomenon in cereals treated with jasmonate methyl ester. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci 2004, 69, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Voisin, D.; Nawrath, C.; Kurdyukov, S.; Franke, R.B.; Reina-Pinto, J.J.; Efremova, N.; Will, I.; Schreiber, L.; Yephremov, A. Dissection of the complex phenotype in cuticular mutants of Arabidopsis reveals a role of SERRATE as a mediator. PLoS Genet 2009, 5, e1000703. [Google Scholar]

- Eckermann, C.; Eichel, J.; Schroder, J. Plant methionine synthase, new insights into properties and expression. Biol. Chem 2000, 381, 695–703. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Wang, A.; Ma, X.; Nevo, E.; Chen, G. Consensus maps of cloned plant cuticle genes. Sci. Cold Arid Reg 2010, 2, 465–476. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, S.; Wen, M.; Bird, D.; Wu, X.; Samuels, L.; Kunst, L.; Jetter, R. The cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP96A15 is the midchain alkane hydroxylase responsible for formation of secondary alcohols and ketones in stem cuticular wax of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2007, 145, 653–667. [Google Scholar]

- Bourquin, V.; Nishikubo, N.; Abem, H.; Brumer, H.; Denman, S.; Eklund, M.; Christiernin, M.; Teeri, T.T.; Sundberg, B.; Mellerowicz, E.J. Xyloglucan Endotransglycosylases have a function during the formation of secondary cell walls of vascular tissues. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 3073–3088. [Google Scholar]

- Nishitani, K. Endo-xyloglucan transferase, a new class of transferase involved in cell wall construction. J. Plant Res 1992, 108, 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi, A.; Mori, H.; Kamisaka, S.; Hoson, T. A new type of endo-xyloglucan transferase devoted to xyloglucan hydrolysis in the cell wall of azuki bean epicotyls. Plant Cell Physiol 2001, 42, 154–161. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Kitamura, S. Cloning and expression of a UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase gene in rice. J. Exp. Bot 2004, 54, 1997–1999. [Google Scholar]

- Izydorczyk, M.S.; Biliaderis, C.G. Cereal arabinoxylans, advances in structure and physicochemical properties. Carbohydr. Polym 1995, 28, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Faik, A.; Price, N.J.; Raikhel, N.V.; Keegstra, K. An Arabidopsis gene encoding an α-xylosyltransferase involved in xyloglucan biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 7797–7802. [Google Scholar]

- Mirouze, M.; Paszkowski, J. Epigenetic contribution to stress adaptation in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol 2011, 14, 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Astolfi, S.; Zuchi, S.; Hubberten, H.M.; Pinton, R.; Hoefgen, R. Supply of sulphur to S-deficient young barley seedlings restores their capability to cope with iron shortage. J. Exp. Bot 2010, 61, 799–806. [Google Scholar]

- Radchuk, V.V.; Sreenivasulu, N.; Radchuk, R.I.; Wobus, U.; Weschke, W. The methylation cycle and its possible functions in barley endosperm development. Plant Mol. Biol 2005, 59, 289–307. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Aguayo, I.; Rodriguez-Galan, J.M.; Garcia, R.; Torreblanca, J.; Pardo, J.M. Salt stress enhances xylem development and expression of S-adenosyl-l-methionine synthase in lignifying tissues of tomato plants. Planta 2004, 220, 278–285. [Google Scholar]

- Fojtova, M.; Kovar, A.; Votruba, I.; Holy, H. Evaluation of the impact of S-adenosylhomocysteine metabolic pools on cytosine methylation of the tobacco genome. Eur. J. Biochem 1998, 252, 347–352. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.H.; Yu, N.; Jiang, S.M.; Shangguan, X.X.; Wang, L.J.; Chen, X.Y. Down-regulation of S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine hydrolase reveals a role of cytokinin in promoting transmethylation reactions. Planta 2008, 228, 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L.; Fong, M.P.; Wang, J.J.; Wei, N.E.; Jiang, H.; Doerge, R.W.; Chen, Z.J. Reversible histone acetylation and deacetylation mediate genome-wide, promoter-dependent and locus-specific changes in gene expression during plant development. Genetics 2005, 169, 337–345. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L.; Chen, Z.J. Blocking histone deacetylation in Arabidopsis induces pleiotropic effects on plant gene regulation and development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 200–205. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Qin, F.; Huang, L.; Sun, Q.; Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, D.X. Rice histone deacetylase genes display specific expression patterns and developmental functions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2009, 388, 266–271. [Google Scholar]

- Caldo, R.A.; Nettleton, D.; Wise, R.P. Interaction-dependent gene expression in Mla-specified response to barley powdery mildew. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2514–2528. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, P.; Baum, M.; Grando, S.; Ceccarelli, S.; Bai, G.; Li, R.; von Korff, M.; Varshney, R.K.; Graner, A.; Valkoun, J. Differentially expressed genes between drought-tolerant and drought-sensitive barley genotypes in response to drought stress during the reproductive stage. J. Exp. Bot 2009, 60, 3531–3544. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, R.P.; Caldo, R.A.; Hong, L.; Shen, L.; Cannon, E.; Dickerson, J.A. BarleyBase/PLEXdb: A Unified Expression Profiling Database for Plants and Plant Pathogens. In Plant Bioinformatics: Methods and Protocols; Edwards, D., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 347–363. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Q.; Wang, X.J. GOEAST: A web-based software toolkit for Gene Ontology enrichment analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 2008, 36, W358–W363. [Google Scholar]

- Custom Primers—OligoPerfect Designer; Invitrogen: Carlsbad, CA, USA, 2006.

- Page, R.D. TreeView: An application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comp. Appl. Biosci 1996, 12, 357–358. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Lang, T.; Li, G.; Chen, G.; Nevo, E. Transcriptome Comparative Profiling of Barley eibi1 Mutant Reveals Pleiotropic Effects of HvABCG31 Gene on Cuticle Biogenesis and Stress Responsive Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 20478-20491. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms141020478

Yang Z, Zhang T, Lang T, Li G, Chen G, Nevo E. Transcriptome Comparative Profiling of Barley eibi1 Mutant Reveals Pleiotropic Effects of HvABCG31 Gene on Cuticle Biogenesis and Stress Responsive Pathways. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013; 14(10):20478-20491. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms141020478

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Zujun, Tao Zhang, Tao Lang, Guangrong Li, Guoxiong Chen, and Eviatar Nevo. 2013. "Transcriptome Comparative Profiling of Barley eibi1 Mutant Reveals Pleiotropic Effects of HvABCG31 Gene on Cuticle Biogenesis and Stress Responsive Pathways" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 10: 20478-20491. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms141020478