Preparation of a Facilitated Transport Membrane Composed of Carboxymethyl Chitosan and Polyethylenimine for CO2/N2 Separation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Membrane Preparation

2.3. Membrane Characterization

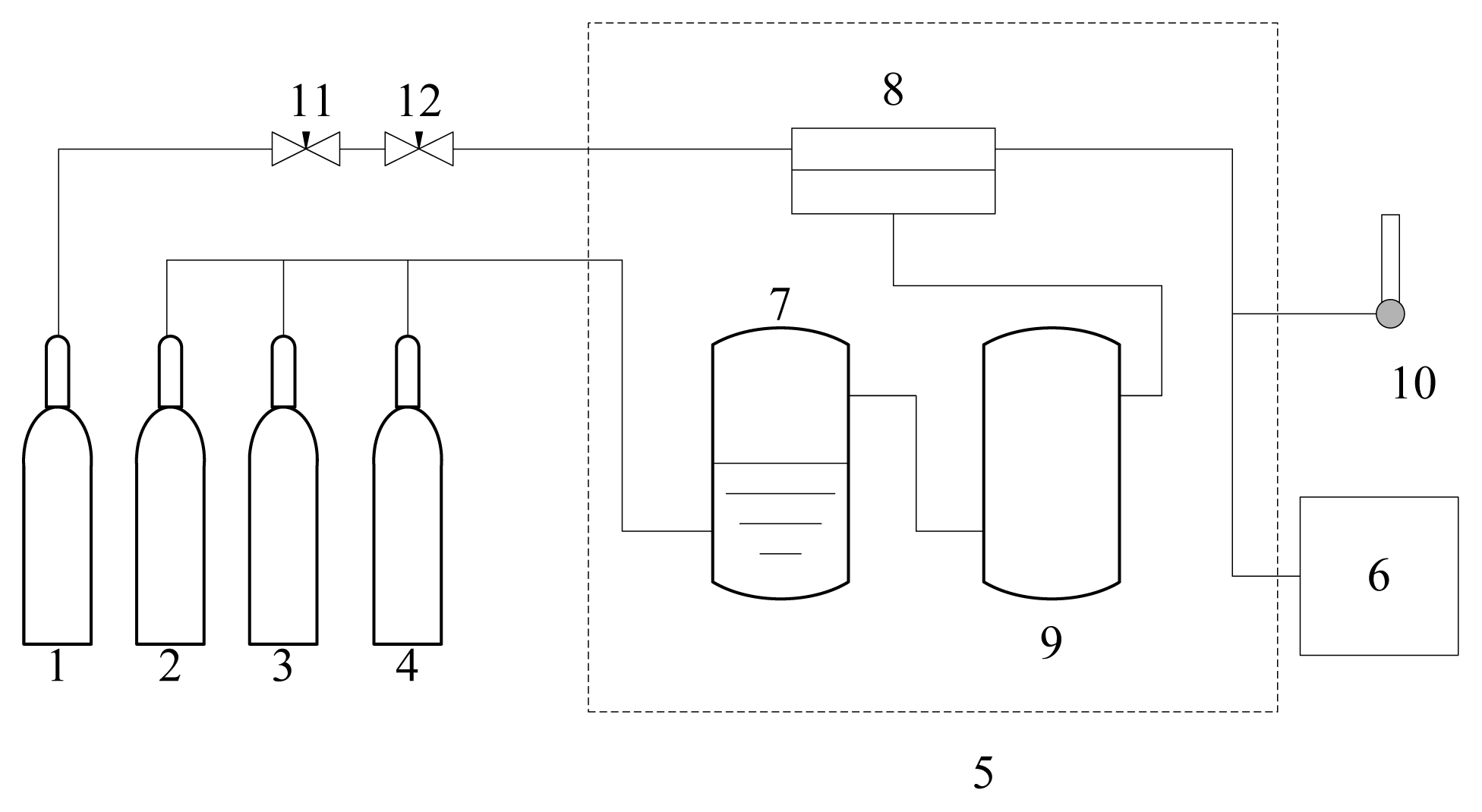

2.4. Permeation Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

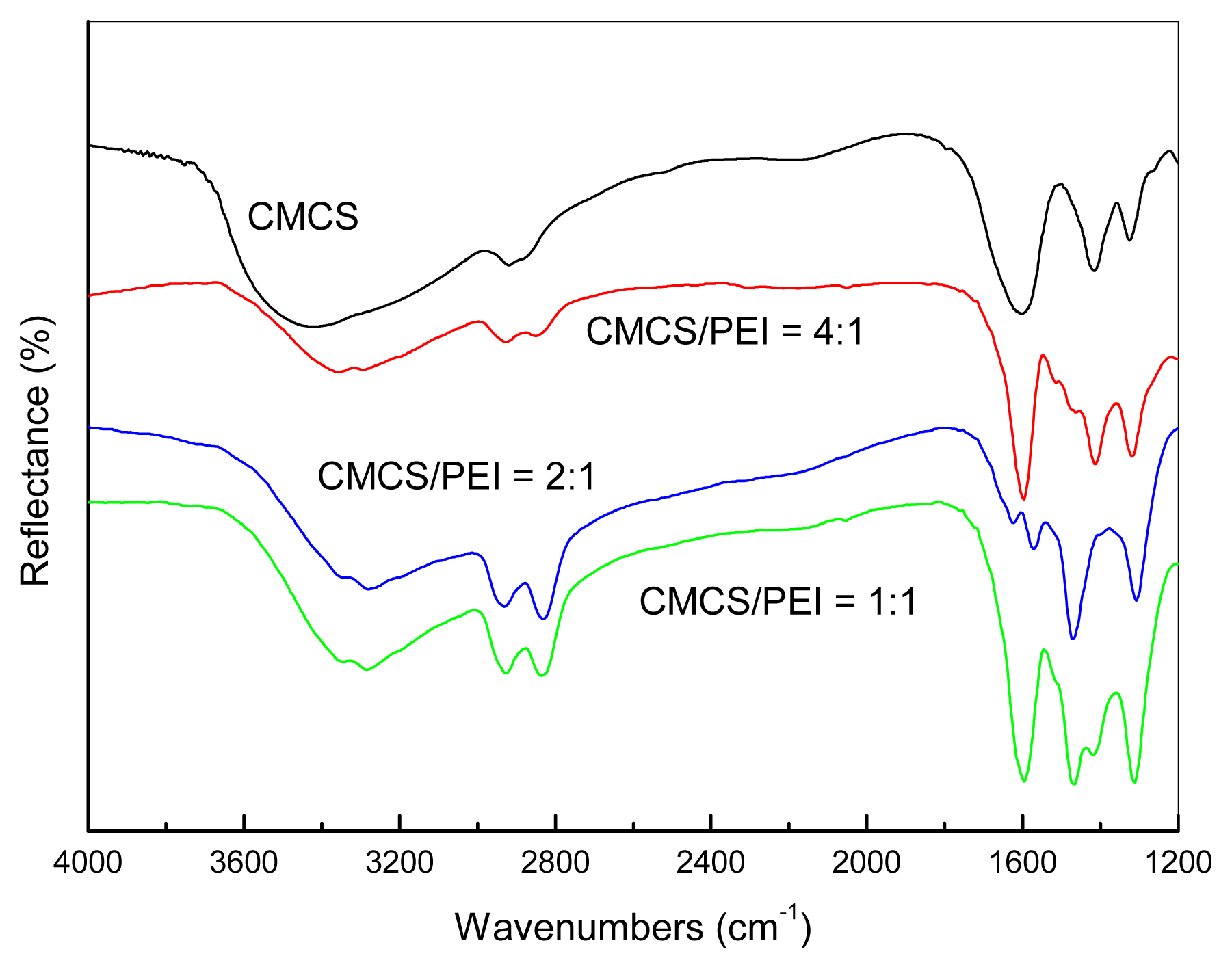

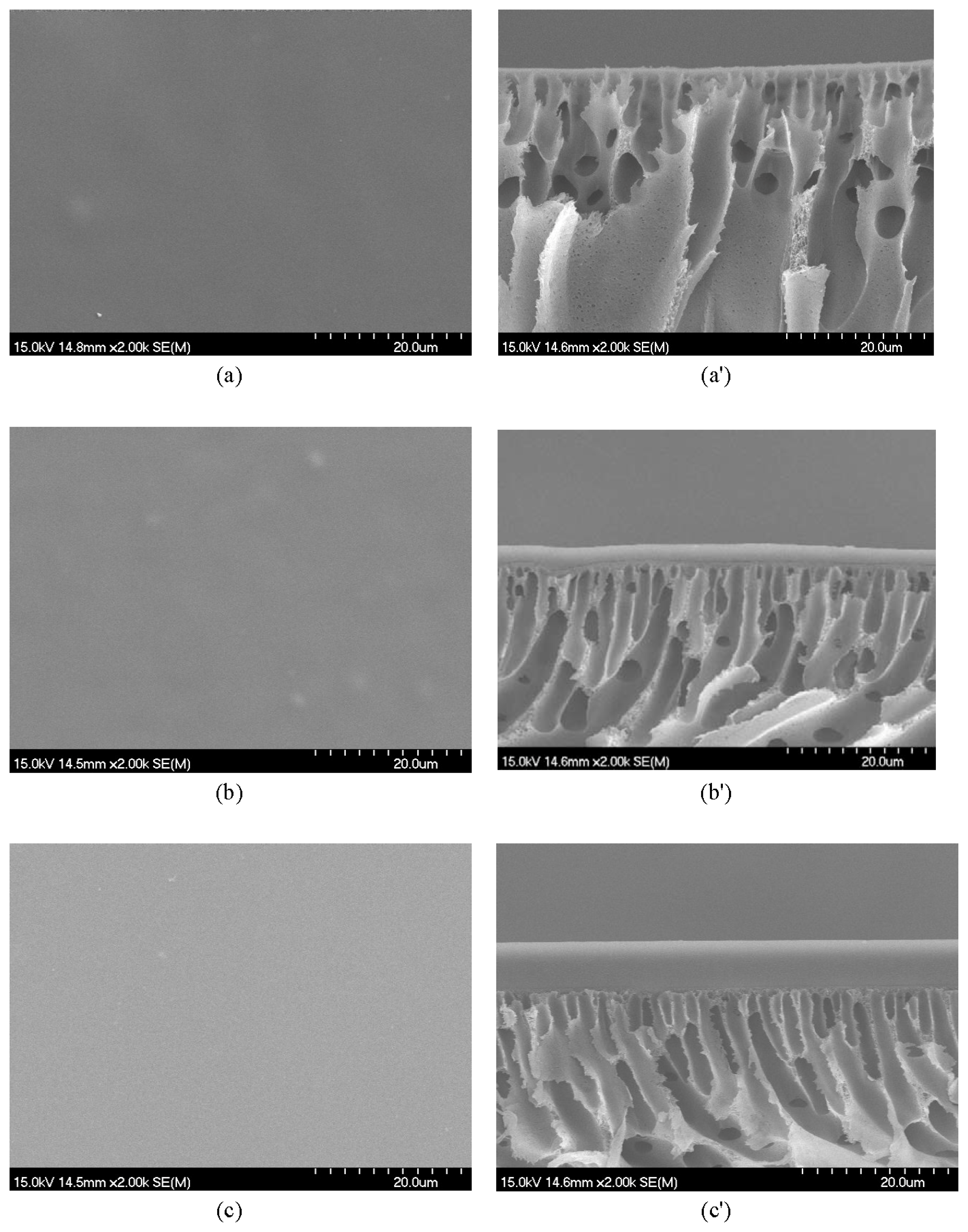

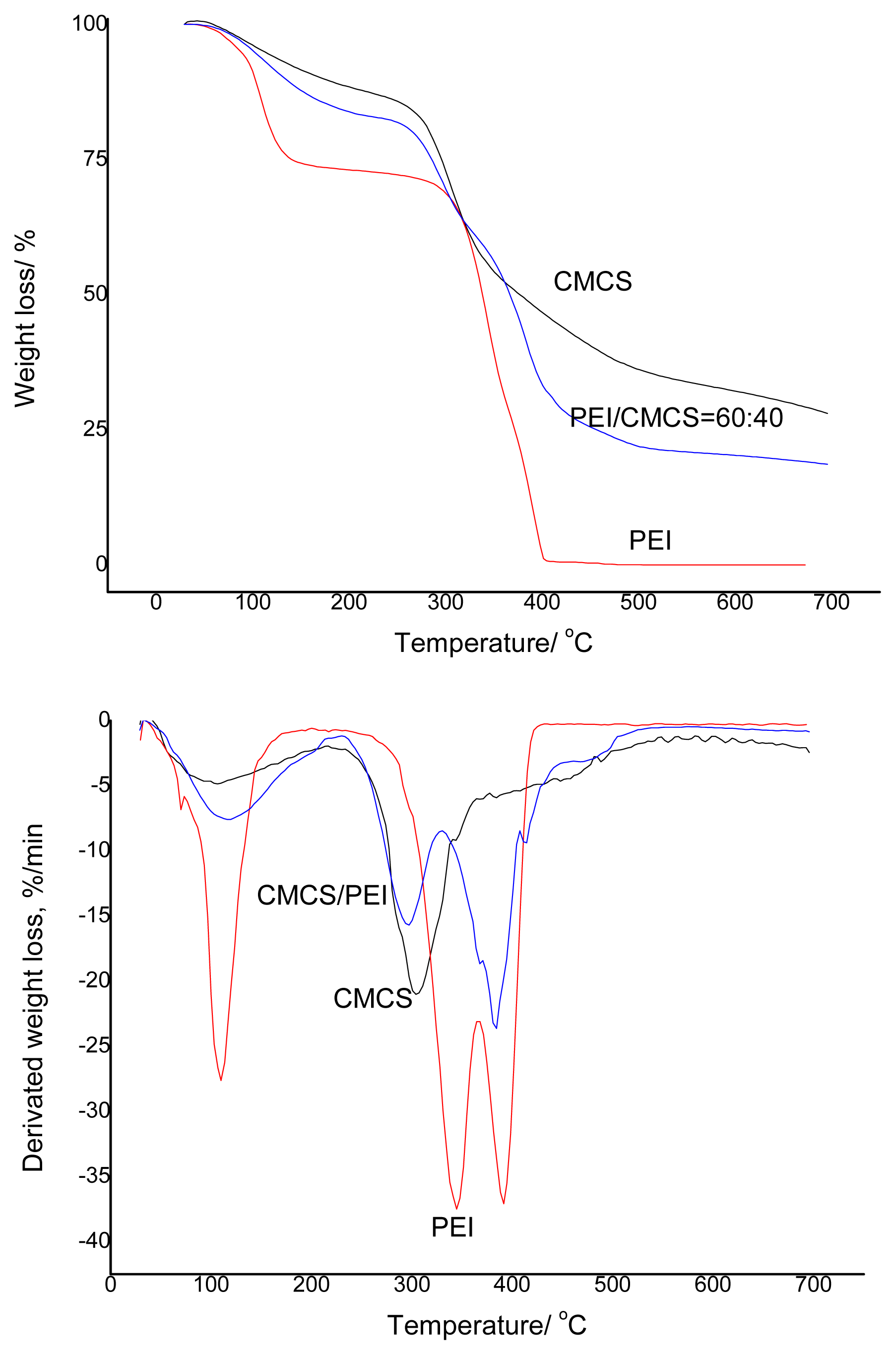

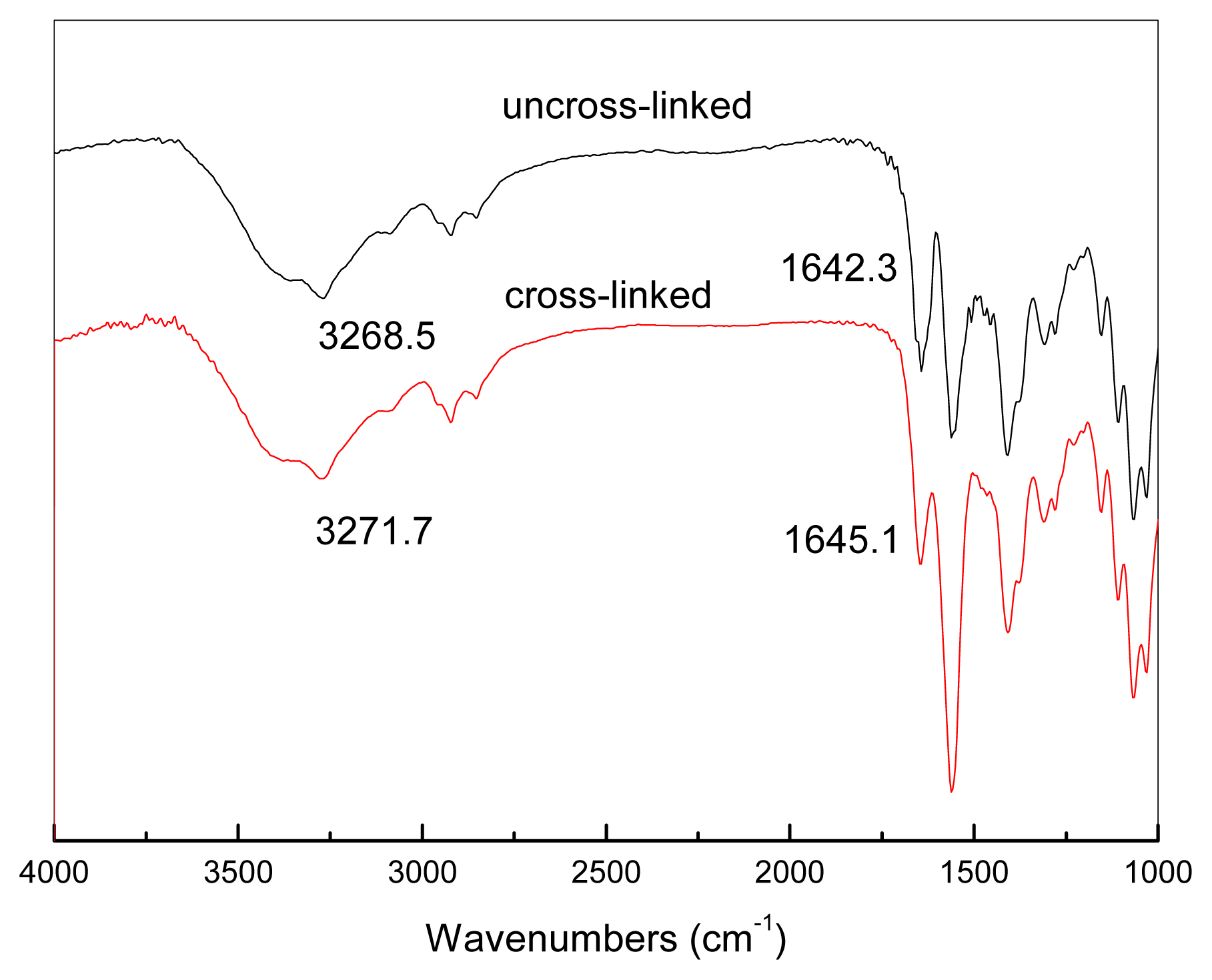

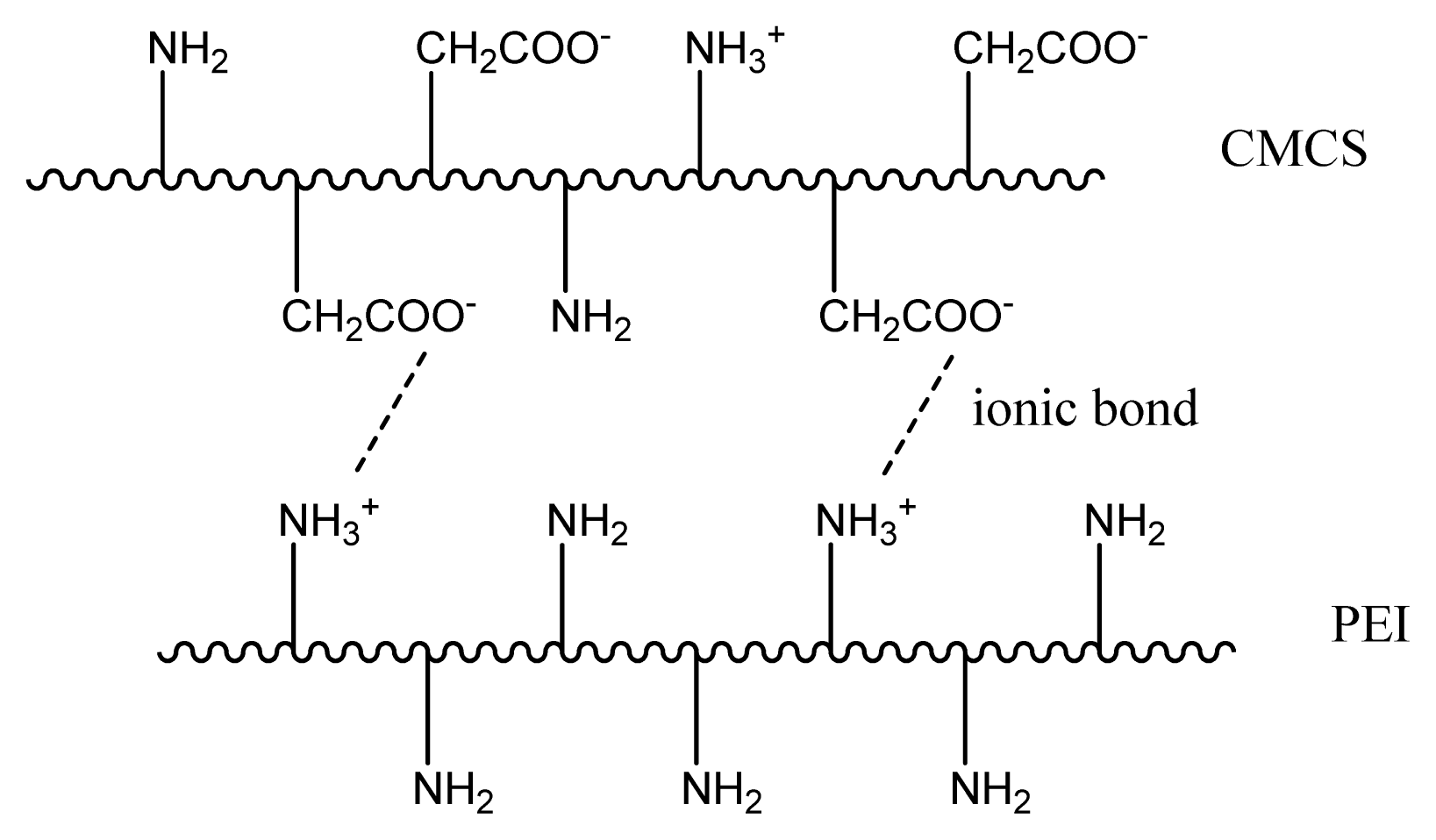

3.1. Miscibility of the CMCS/PEI Blends

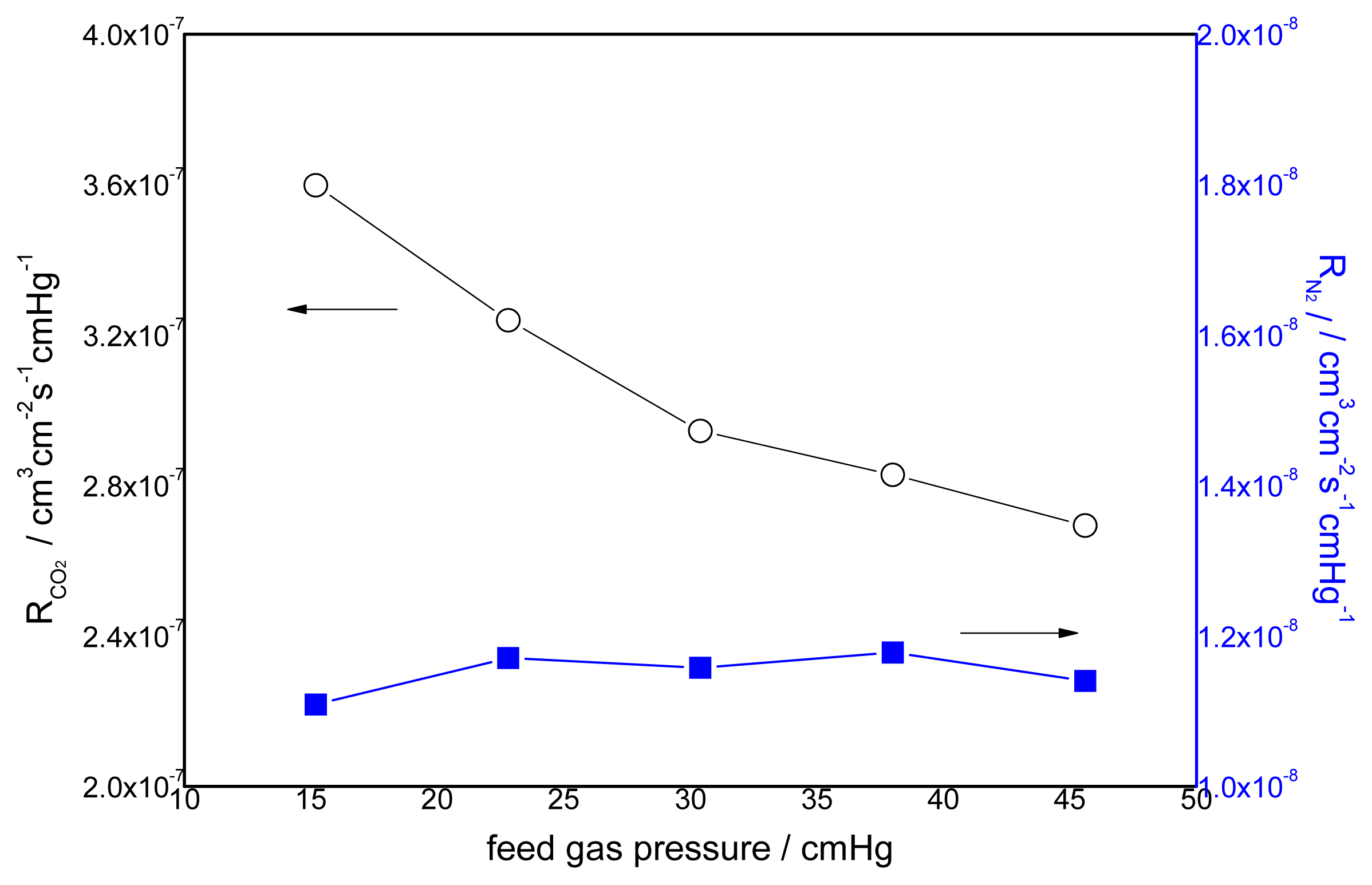

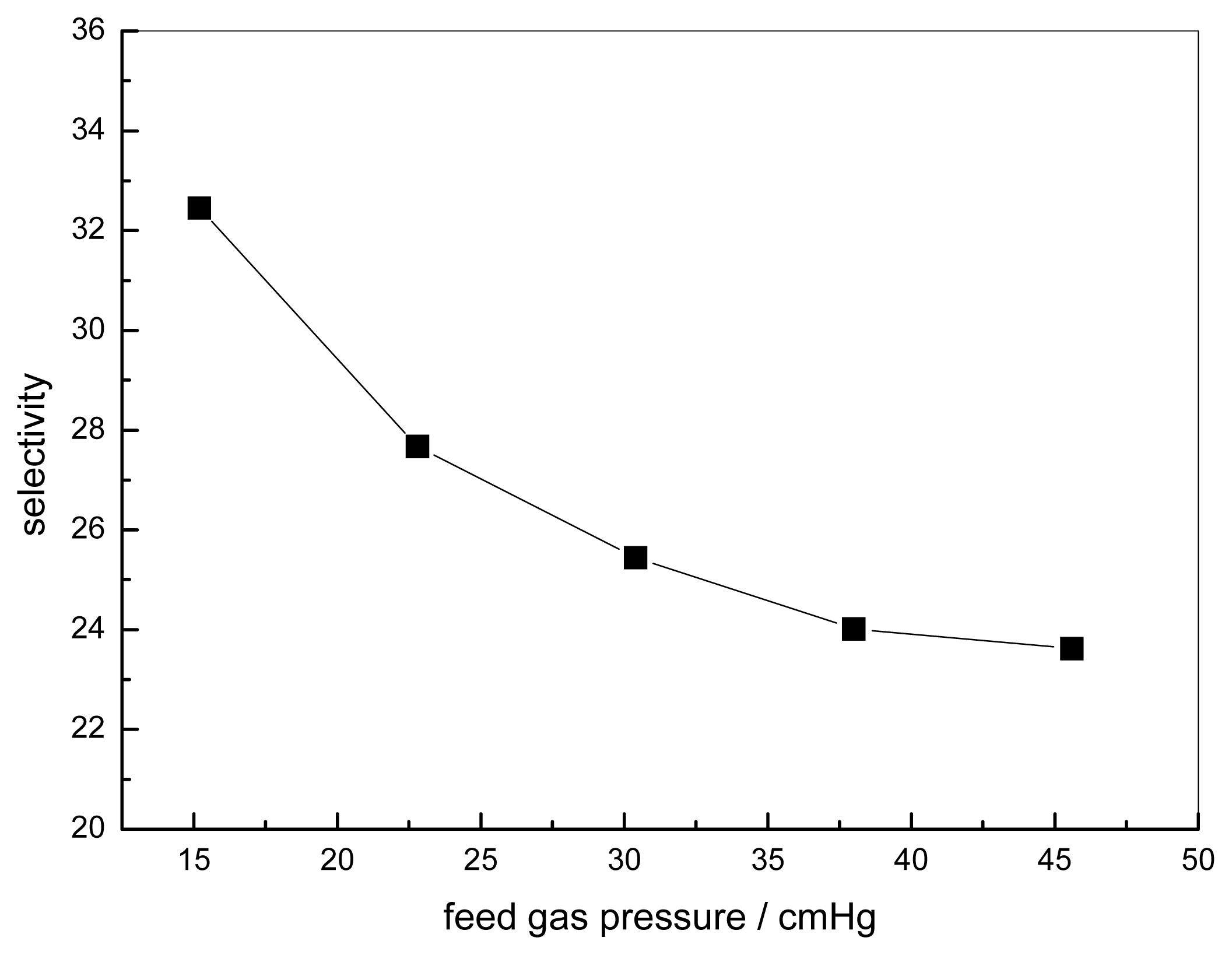

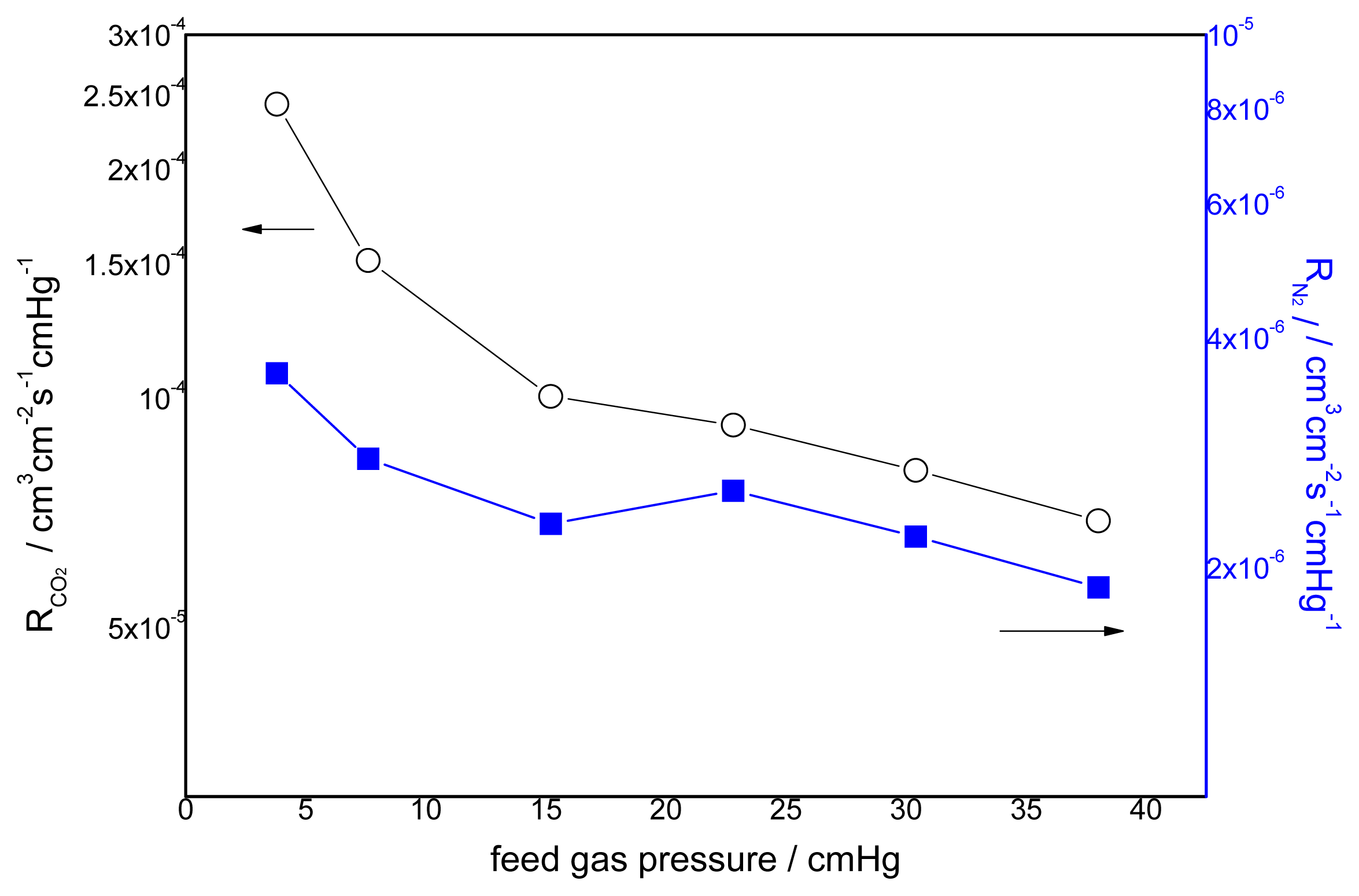

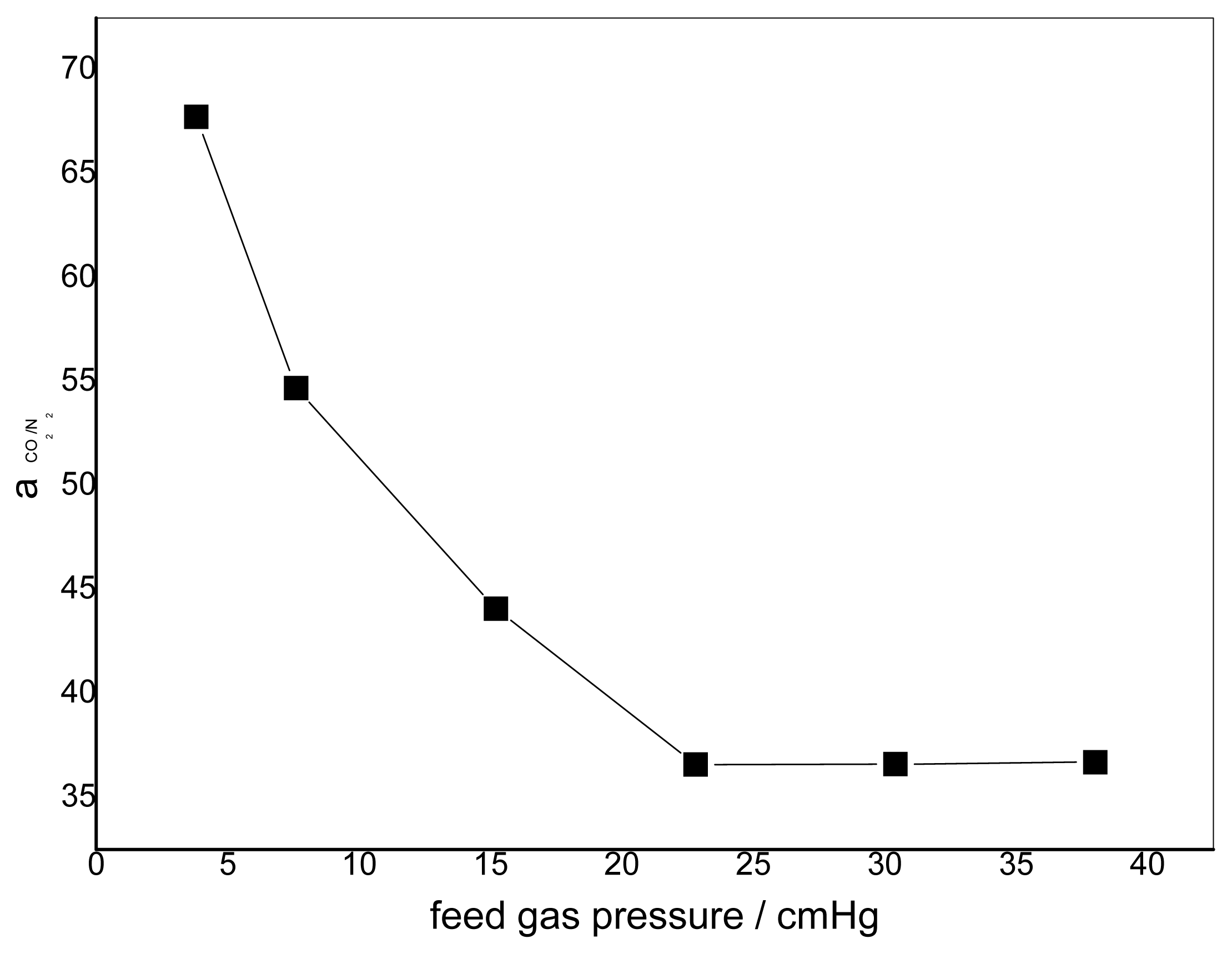

3.2. Effect of Feed Gas Pressure on the Performance of Non-Crosslinked Blended Membrane without Water

3.3. Effect of the Feed Gas Pressure on the Performance of Acid Treated Blended Membranes Containing Water

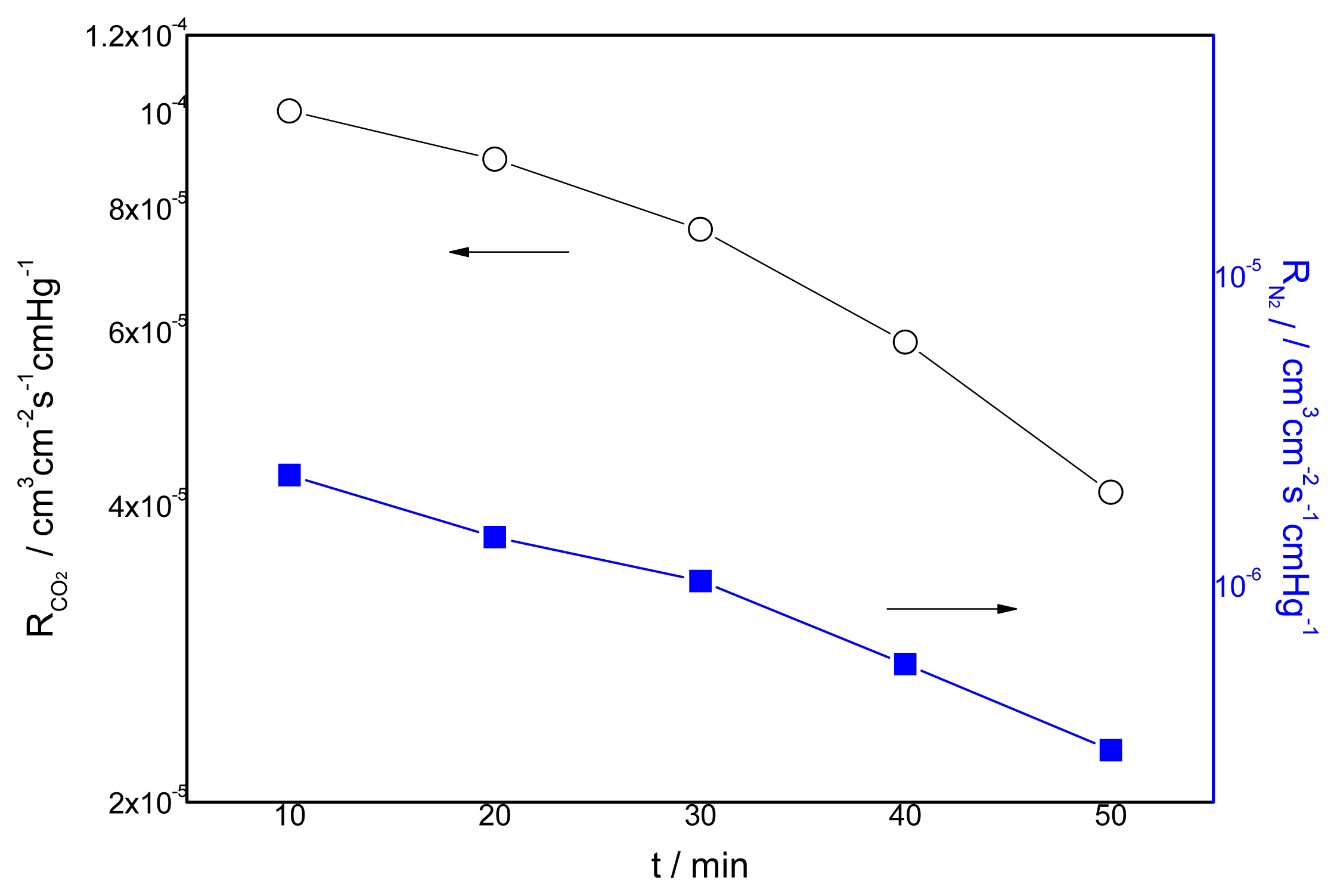

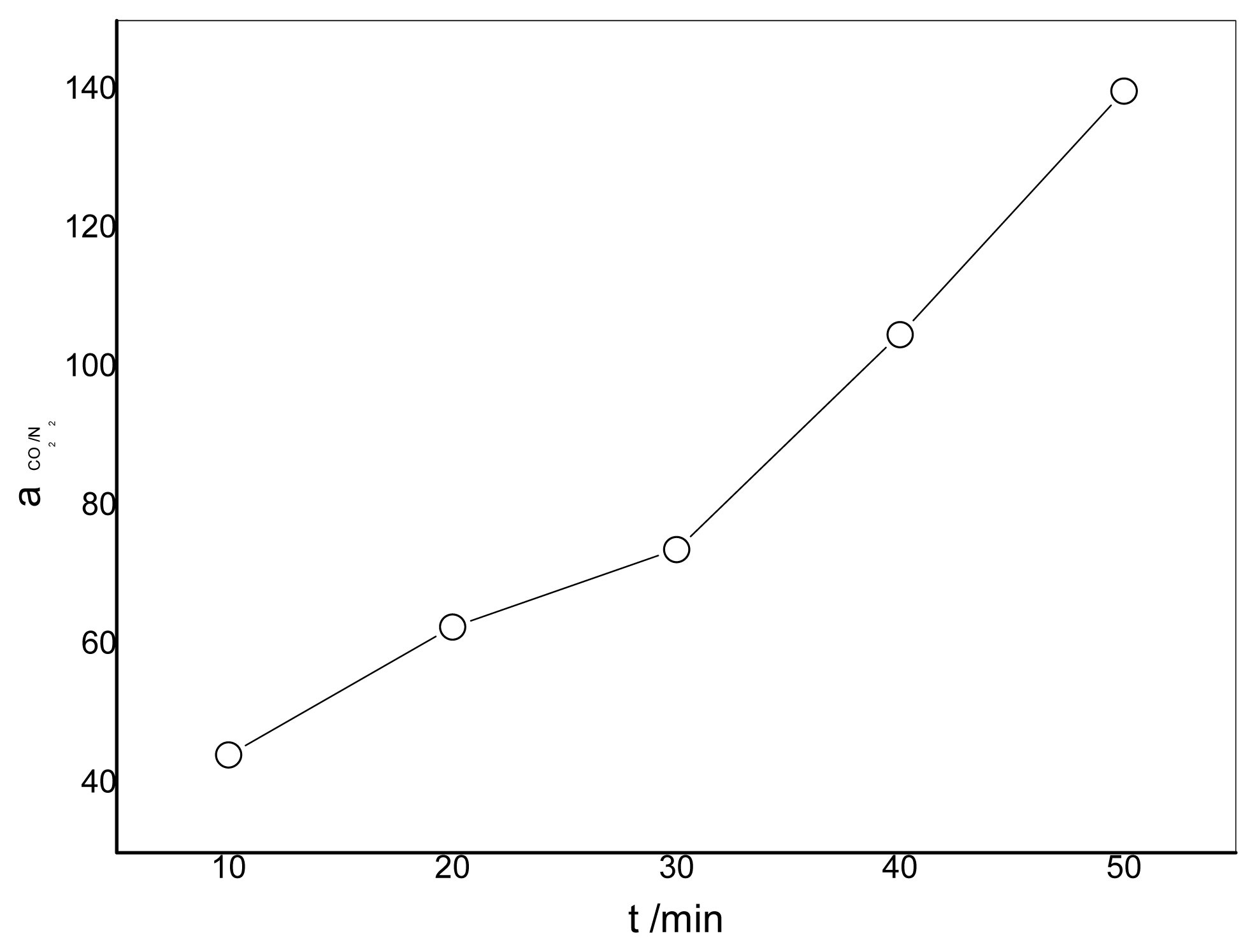

3.4. Effect of the Duration of Acid Treatment on the Performance of Blended Membranes

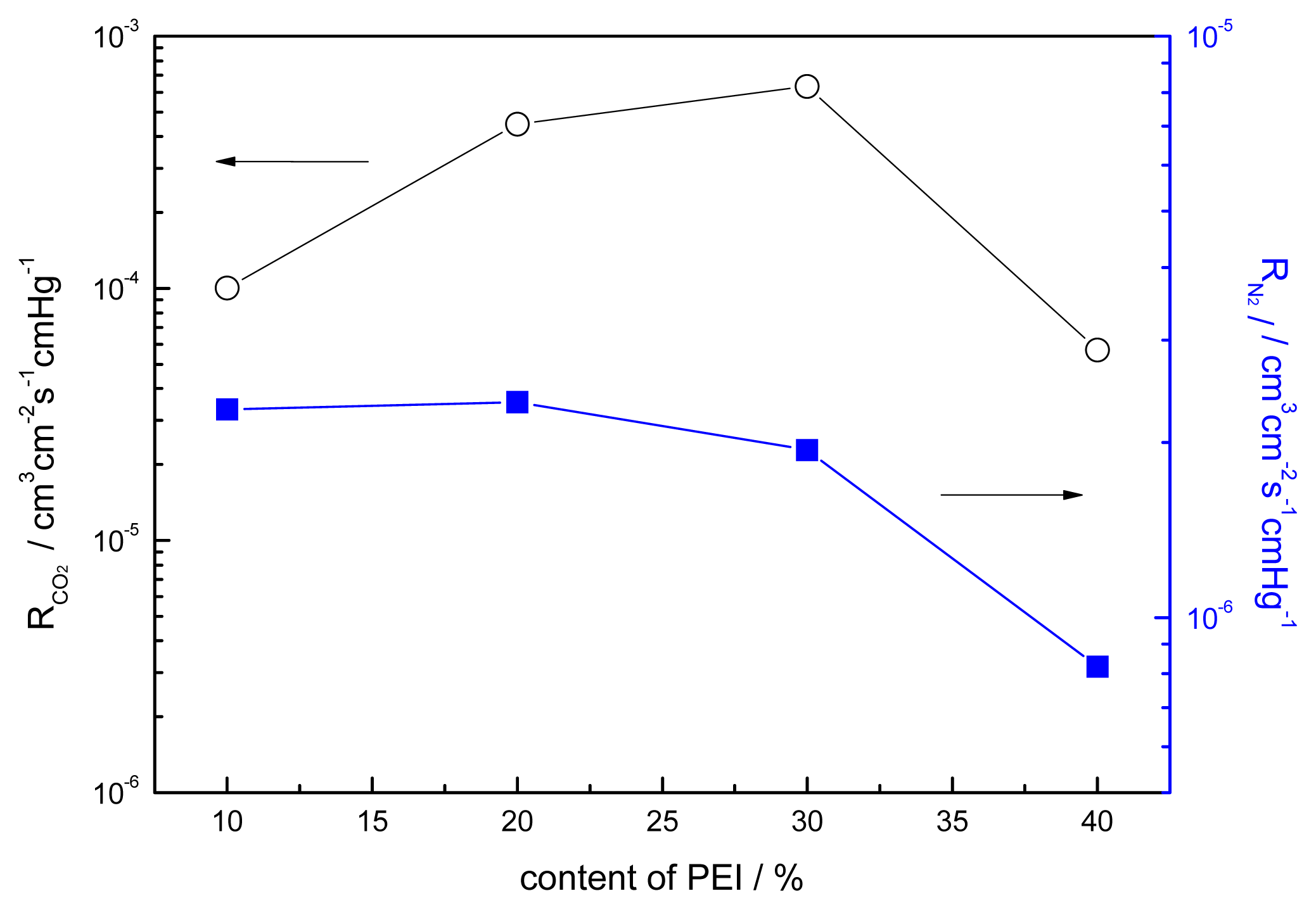

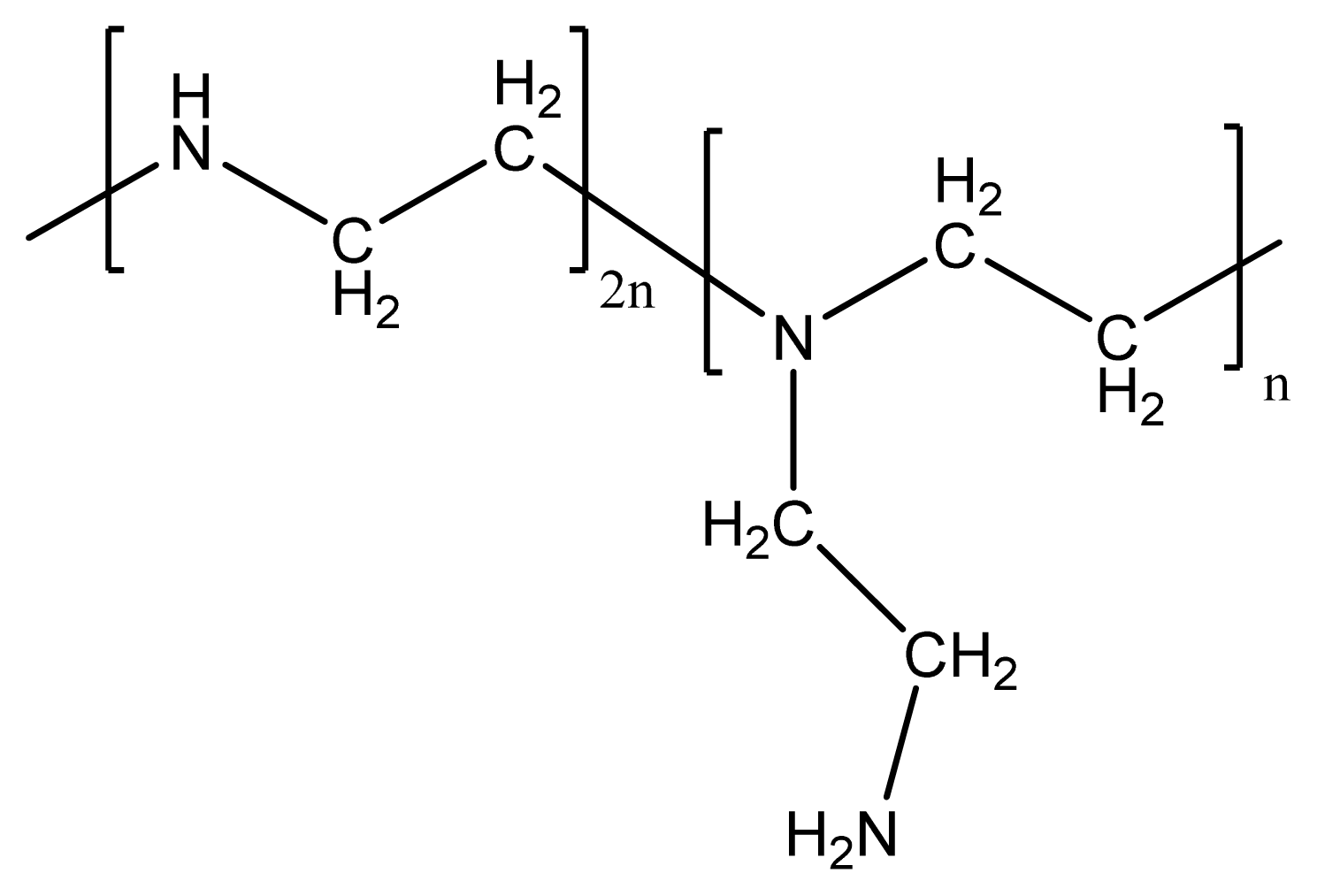

3.5. Effect of the Content of PEI on the Performance of Blended Membranes

4. Comparison with Membrane Separation Performance Reported in the Literature

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Richard, W.B. Future directions of membrane gas separation technology. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 2002, 41, 1393–1411. [Google Scholar]

- Robeson, L.M. Polymer membranes for gas separation. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci 1999, 4, 549–552. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Fujimoto, K.; Toshio, H.K.K.; Naoya, O. Selective Permeation of carbon-dioxide through synthetic polymeric membranes having amine moiety. Chem. Lett 1994, 2, 243–246. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, M. Basic Principles of Membrane Technology; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996; pp. 340–365. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, G.Y.; Krantz, W.B. Formation and charactorization of polyamide membranes via interfacial polymerization. J. Membr. Sci 1994, 93, 175–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hagg, M.B.; Quinn, R. Polymeric facilitated transport membranes for hydrogen purification. MRS Bull 2006, 31, 750–755. [Google Scholar]

- Scholes, C.A.; Kentish, S.E.; Stevens, G.W. Effect of water in ionic liquids on CO2 permeability in amino acid ionic liquid-based facilitated transport membranes. J. Membr. Sci 2012, 415–416, 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yi, C.H.; Bai, Y.H.; Wang, J.X.; Wang, S.C. Gas transport property of polyallylamine-poly(vinyl alcohol)/polysulfone composite membranes. J. Membr. Sci 2008, 310, 184–196. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama, H.; Terada, A.; Nakagawara, T.; Kitamura, Y.; Teramoto, M. Facilitated transport of CO2 through polyethylenimine/poly(vinyl alcohol) blend membrane. J. Membr. Sci 1999, 163, 221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara, S.; Kamio, E.; Ishigami, T.; Matsuyama, H. Carbon dioxide separation through polymeric membrane systems for flue gas applications. Recent Pat. Chem. Eng 2008, 1, 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kapantaidakis, G.C.; Koops, G.H. High flux polyethersulfone-polyimide blend hollow fiber membranes for gas separation. J. Membr. Sci 2002, 204, 153–171. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.N.; Ruan, H.M.; Gao, C.J. Preparation and characterization of CMCS/PVA blend membranes and its sorption and pervaporation performance (I). J. Appl. Polym. Sci 2009, 114, 3369–3378. [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda, S.B.; NguyenB, Q.T.; Langevin, D.; Roudesli, S. Poly(vinylalcohol)/ poly(ethyleneglycol)/poly(ethyleneimine) blend membranes-structure and CO2 facilitated transport. C. R. Chim 2010, 13, 372–379. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, R.; Ho, W.S.W. Synthesis and characterization of crosslinked Polyvinylalcohol/polyethyleneglycol blend membranes for CO2/CH4 separation. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng 2009, 40, 654–662. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S.; Shen, J.N.; Qiu, J.H. Miscibility study of polymer blends composed of polyethylenimine, polyethyleneglycol, and carboxymethyl chitosan. Adv. Mater. Res 2011, 284, 1707–1712. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, R.K.; Huang, M.Y.; Jiang, Y.Y. Selective permeabilities of chitosan-acetic acid complex membrane and chitosan-polymer complex membranes for oxygen and carbon dioxide. Polym. Bull 1988, 20, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gontard, N.; Thibault, R.; Cuq, B.; Guilbert, S. Influence of relative humidity and film composition on oxygen and carbon dioxide permeabilities of edible films. J. Agric. Food Chem 1996, 44, 1064–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, A.; Sato, M.; Anma, T. Permeability of CO2 through chitosan membrane swollen by water vapor in feed gas. Angew. Makromol. Chem 1997, 248, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, S.Y.; Lee, K.H.; Yi, S.C.; Kim, H.T.; Kumazawa, H. CO2, N2-gas sorption and permeation behavior of chitosan membrane. Korean J. Chem. Eng 1998, 15, 223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Despond, S.; Espuche, E.; Domard, A. Water sorption and permeation in chitosan films: Relation between gas permeability and relative humidity. J. Polym. Sci. B 2001, 39, 3114–3127. [Google Scholar]

- El-Azzami, L.A.; Grulke, E.A. Carbon dioxide separation from hydrogen and nitrogen by fixed facilitated transport in swollen chitosan membranes. J. Membr. Sci 2008, 323, 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Preparation and Performance of Fixed Carrier Composite Membranes for Separation of CO2/CH4 Mixtures. Ph.D. Dissertation, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Guo, J.; Zhou, J.; Yang, G.; Du, Y. Blend membranes from carboxylated chitosan/alginate in aqueous solution. J. Appl. Polym. Sci 2000, 77, 610–616. [Google Scholar]

- Boricha, A.G.; Murthy, Z.V.P. Preparation of N,O-carboxymethyl chitosan/cellulose acetate blend nanofiltration membrane and testing its performance in treating industrial wastewater. Chem. Eng. J 2010, 157, 393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Sreedhar, B.; Aparna, Y.; Sairam, M.; Hebalkar, N. Preparation and characterization of HAP/carboxymethyl chitosan nanocomposites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci 2007, 105, 928–934. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, J.; Ho, W.S.W. CO2-selective polymeric membranes containing amines in crosslinked poly(vinyl alcohol). J. Membr. Sci 2006, 286, 310–321. [Google Scholar]

- Gumusoglu, T.; Ari, G.A.; Deligoz, H. Investigation of salt addition and acid treatment effects on the transport properties of ionically cross-linked polyelectrolyte complex membranes based on chitosan and polyacrylic acid. J. Membr. Sci 2011, 376, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.X.; Wang, S.C. Facilitated transport of CO2 through microporous membranes using water as carrier (In Chinese). J. Chem. Ind. Eng 2002, 3, 231–232. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Qiu, J.; Wu, L.; Gao, C. Facilitated transport of carbon dioxide through poly(2-N,N-dimethyl aminoethyl methacrylate-co-acrylic acid sodium) membrane. Sep. Purif. Technol 2006, 51, 345–351. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, C.H.; Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, J.X.; Wang, S.C. Facilitated transport of CO2 through polyvinylamine/polyethlene glycol blend membranes. Desalination 2006, 193, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.J.; Li, B.A.; Hagg, M.B. Novel fixed-site-carrier polyvinylamine membrane for carbon dioxide capture. J. Polym. Sci. B 2004, 42, 4326–4336. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.Y.; Kim, T.J.; Hagg, M.B. Facilitated transport of CO2 in novel PVAm/PVA blend Membrane. J. Membr. Sci 2009, 340, 154–163. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.Y.; Hagg, M.B. Swelling behavior and gas permeation performance of PVAm/PVA blend FSC membrane. J. Membr. Sci 2010, 363, 295–301. [Google Scholar]

- El-Azzami, L.A.; Grulke, E.A. Carbon dioxide separation from hydrogen and nitrogen facilitated transport in arginine salt-chitosan membranes. J. Membr. Sci 2009, 328, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

| Blend ratio of CMCS/PEI | 90/10 | 80/20 | 70/30 | 60/40 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEI content (wt%) | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 |

| Membrane material | Selectivity/separation factor | Permeance (cm3 cm−2 s−1 cmHg−1) or permeability * | ΔP (cmHg) | Feed gas (CO2%) (v/v) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEI/PVA (32.7%/67.3%) | 160 | 3.9 × 10−6 | 5.016 | pure CO2 and N2 | [9] |

| PEI/PEG/PVA (PEI: 45%) | 100–250 | PCO2:250 Barrer * | 76 | pure CO2 and N2 | [13] |

| PVAm/PEG (90%/10%) | 63.1 | 5.8 × 10−6 | 96 | pure CO2 and CH4 | [30] |

| PVAm | 1000 | 5.1 × 10−6 | 152 | Pure CO2 and CH4 | [31] |

| PVAm/PVA (80%/20%) | 174 | 2.1 × 10−4 | 152 | CO2/N2 (10%) | [32] |

| PVAm/PVA contaiing water (80%/20%) | 160 | 3.0 × 10−4 | 152 | CO2/N2 (10%) | [33] |

| CS/PAm (50%/50%) | O2/CO2 0.074 | 1.18 × 10−11 | 10 | pure CO2 and O2 | [16] |

| Swollen CS | 70 | 2.5 × 10−8 | 25.4 | CO2/N2 | [18] |

| Swollen CS | CO2/N2 250 | 4.8 × 10−8 | 15 | CO2/N2/H2 (10/80/10) | [21] |

| Swollen CS/arginine salt (60%/40%) | CO2/N2 852 | 1.5 × 10−7 | 11.4 | CO2/N2/H2 (10/80/10) | [34] |

| Amino acid ionic liquid-based facilitated transport membranes | 100 | 14,000 Barrer | 76 | pure CO2 and N2 | [7] |

| Polyvinylalcohol (cross linked formaldehyde) | 338 | 1728 Barrer | 76~152 | Gas Mixtures of 40/20/40 or 75/25/0 of H2, CO2 with N2 | [10] |

| Dry CMCS/PEI (95%/5%) | 33 | 3.6 × 10−7 | 15.2 | pure CO2 and N2 | This work |

| CMCS/PEI Containing water (70%/30%) | 325 | 6.3 × 10−4 | 15.2 | CO2/N2 (10/90) | This work |

© 2013 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, J.-N.; Yu, C.-C.; Zeng, G.-N.; Van der Bruggen, B. Preparation of a Facilitated Transport Membrane Composed of Carboxymethyl Chitosan and Polyethylenimine for CO2/N2 Separation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 3621-3638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14023621

Shen J-N, Yu C-C, Zeng G-N, Van der Bruggen B. Preparation of a Facilitated Transport Membrane Composed of Carboxymethyl Chitosan and Polyethylenimine for CO2/N2 Separation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013; 14(2):3621-3638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14023621

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Jiang-Nan, Chang-Chao Yu, Gan-Ning Zeng, and Bart Van der Bruggen. 2013. "Preparation of a Facilitated Transport Membrane Composed of Carboxymethyl Chitosan and Polyethylenimine for CO2/N2 Separation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 2: 3621-3638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14023621