Study of Fungal Colonization of Wheat Kernels in Syria with a Focus on Fusarium Species

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Fungal Isolation

3.2. Genomic DNA Isolation and Qualitative PCR

3.3. Mycotoxin Detection

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- El-Khalifeh, M.; El-Ahmed, A.; Al-Saleh, A.; Nachit, M. Use of AFLPs to differentiate between Fusarium species causing root rot disease on durum wheat (Triticum turgidum L. var. durum). Afr. J. Biotechnol 2009, 8, 4347–4352. [Google Scholar]

- SYRIA: Wheat Production in 2008/09 Declines Owing to Season-Long Drought. Available online: http://www.pecad.fas.usda.gov/highlights/2008/05/Syria_may2008.htm accessed on 9 May 2008.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Fertilizer Use by Crop in the Syrian Arab Republic. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/005/Y4732E/y4732e06.htm accessed on 8 July 2003.

- National Agricultural Policy Center (NAPC), Study on Supply and Demand Prospects for the Major Syrian Agricultural Products; National Agricultural Policy Center: Syria, 2009.

- Goswami, R.; Kistler, H. Heading for disaster: Fusarium graminearum on cereal crops. Molecular. Plant Pathol 2004, 5, 515–525. [Google Scholar]

- El-Khalifeh, M.; El-Ahmed, A.; Yabrak, M.; Nachit, M. Variation of cultural and morphological characteristics in Fusarium spp. pathogens of common root rot disease on wheat in Syria. Arab. J. Plant Prot 2006, 24, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, P.; Chandler, E.; Draeger, R.; Gosman, N.; Simpson, D.; Thomsett, M.; Wilson, A. Molecular tools to study epidemiology and toxicology of Fusarium head blight of cereals. Eur. J. Plant Pathol 2003, 109, 691–703. [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins, A. Fusarium Mycotoxins: Chemistry, Genetics and Biology; APS Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2006; p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- Saberi-Riseh, R.; Javan-Nikkhah, M.; Heidarian, R.; Hosseini, S.; Soleimani, P. Detection of fungal infectious agent of wheat grains in store-pits of Markazi province, Iran. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci 2004, 69, 541–544. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, G.; Shaner, G. Scab of wheat: Prospects for control. Plant Dis 1994, 78, 760–766. [Google Scholar]

- Talas, F.; Longin, F.; Miedaner, T. Sources of resistance to Fusarium head blight within Syrian durum wheat landraces. Plant Breed 2011, 130, 398–400. [Google Scholar]

- Alkadri, D. Fusarium Species Responsible for Mycotoxin Production in Wheat Crop: Involvement in Food Safety. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stack, R.W.; Elias, E.M.; Fetch, J.M.; Miller, J.D.; Joppa, L.R. Fusarium head blight reaction of Langdon durum—Triticum dicoccoides chromosome substitution lines. Crop Sci 2002, 42, 637–642. [Google Scholar]

- Bottalico, A.; Perrone, G. Toxigenic Fusarium species and mycotoxins associated with head blight in small-grain cereals in Europe. Eur. J. Plant Pathol 2002, 108, 611–624. [Google Scholar]

- Arabi, M.; Jawhar, M. Heterogeneity in Fusarium species as revealed by inter-retrotransposon amplified polymorphism (irap) analysis. J. Plant Pathol 2010, 92, 753–757. [Google Scholar]

- Quarta, A.; Mita, G.; Haidukowski, M.; Santino, A.; Mulè, G.; Visconti, M. Assessment of trichothecene chemotypes of Fusarium culmorum occurring in Europe. Food Addit. Contam 2005, 22, 309–315. [Google Scholar]

- Prodi, A.; Salomoni, D.; Alkadri, D.; Tonti, S.; Nipoti, P.; Pisi, A.; Pancaldi, D. Presence of deoxynivalenol and nivalenol chemotypes of Fusarium culmorum isolated from durum wheat in some Italian regions. J. Plant Pathol 2010, 92, 96. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, P.; Coates, M.; Chandler, A.; Turner, J.; Nicholson, P. Determination of deoxynivalenol and nivalenol chemotypes of Fusarium culmorum isolates from England and Wales by PCR assay. Plant Pathol 2004, 53, 182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquali, M.; Giraud, C.; Brochot, E.; Cocco, L.; Hoffmann, T.; Bohn, T. Genetic Fusarium chemotyping as a useful tool for predicting nivalenol contamination in winter wheat. Int. J. Food Microbiol 2010, 137, 246–253. [Google Scholar]

- Starkey, D.; Ward, T.; Aoki, T.; Gale, L.; Kistler, H.; Geiser, D.; Suga, H.; Toth, B.; Varga, J.; O’Donnell, K. Global molecular surveillance reveals novel Fusarium head blight species and trichothecene toxin diversity. Fungal Genet. Biol 2007, 44, 1191–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Niessen, L.; Vogel, R. Group specific PCR-detection of potential trichothecene producing Fusarium-species in pure cultures and cereal samples. Syst. Appl. Microbiol 1998, 21, 618–631. [Google Scholar]

- Tokai, T.; Takahashi-Ando, N.; Izawa, M.; Kamakura, T.; Yoshida, M.; Fugimura, M.; Kimura, M. 4-O-acetylation and 3-O-acetylation of trichothecenes by trichothecene 15-O-acetyltransferase encoded by Fusarium Tri3. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2008, 72, 2485–2489. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, N.J.; McCormick, S.P.; Waalwijk, C.; van der Lee, T.; Proctor, R.H. The genetic basis for 3-ADON and 15-ADON trichothecene chemotypes in Fusarium. Fungal Genet. Biol 2011, 48, 485–495. [Google Scholar]

- Bakan, B.; Giraud-Delville, C.; Pinson, L.; Richard-Molard, D.; Fournier, E.; Brygoo, Y. Identification by PCR of Fusarium culmorum strains producing large and small amounts of deoxynivalenol. Appl. Environ. Microb 2002, 68, 5472–5479. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, K.; Thrane, U. Fast methods for screening of trichothecenes in fungal cultures using gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2001, 929, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Mugrabi de Kuppler, A.L.; Steiner, U.; Sulyok, M.; Krska, R.; Oerke, E.C. Genotyping and phenotyping of Fusarium graminearum isolates from Germany related to their mycotoxin biosynthesis. Int. J. Food Microbiol 2011, 151, 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.; Han, Y.K.; Kim, K.H.; Yun, S.H.; Lee, Y.W. Tri13 and Tri7 determine deoxynivalenol- and nivalenol-producing chemotypes of Gibberella zeae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2002, 68, 2148–2154. [Google Scholar]

- Haratian, M.; Sharifnabi, B.; Alizadeh, A.; Safaie, N. PCR Analysis of the Tri13 gene to determine the genetic potential of Fusarium graminearum isolates from Iran to produce nivalenol and deoxynivalenol. Mycopathologia 2008, 166, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Waalwijk, C.; Kastelein, P.; de Vries, I.; Kerenyi, Z.; van der Lee, T.; Hesselink, T.; Kohl, J.; Kema, G. Major changes in Fusarium spp. in wheat in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Plant Pathol 2003, 109, 743–754. [Google Scholar]

- Prodi, A.; Tonti, S.; Nipoti, P.; Pancaldi, D.; Pisi, A. Identification of deoxynivalenol and nivalenol producing chemotypes of Fusarium graminearum isolates from durum wheat in a restricted area of northern Italy. J. Plant Pathol 2009, 91, 727–732. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, L.; Ward, T.; Balmas, V.; Kistler, H. Population subdivision of Fusarium graminearum sensu stricto in the upper Midwestern United States. Phytopathology 2007, 97, 1434–1439. [Google Scholar]

- Yli-Mattila, T.; O’Donnell, K.; Ward, T.; Gagkaeva, T. Trichothecene chemotype composition of Fusarium graminearum and related species in Finland and Russia. J. Plant Pathol 2008, 90, S60. [Google Scholar]

- Langseth, W.; Bernhoft, A.; Rundberget, T.; Kosiak, B.; Gareis, M. Mycotoxin production and cytotoxicity of Fusarium strains isolated from Norwegian cereals. Mycopathologia 1999, 144, 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, P.; Moretti, A.; Ritieni, A.; Jurado, M.; Vázquez, C.; González-Jaén, M.T. Phylogenetic analyses and toxigenic profiles of Fusarium equiseti and Fusarium acuminatum isolated from cereals from Southern Europe. Food Microbiol 2012, 31, 229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Monds, R.D.; Cromey, M.G.; Lauren, D.R.; di Menna, M.; Marshall, J. Fusarium graminearum, F. cortaderiae and F. pseudograminearum in New Zealand: Molecular phylogenetic analysis, mycotoxin chemotypes and co-existence of species. Mycol. Res 2005, 109, 410–420. [Google Scholar]

- Pancaldi, D.; Tonti, S.; Prodi, A.; Salomoni, D.; Dal Prà, M.; Nipoti, P.; Alberti, I.; Pisi, A. Survey of the main causal agents of Fusarium head blight of durum wheat around Bologna, northern Italy. Phytopathol. Medit 2010, 49, 258–266. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, T. Pictorial Atlas of Soil and Feed Fungi, Morphology of Cultured Fungi and Key to Species, 2nd ed; CRC Press: London, UK, 2002; p. 486. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, J.; Summerell, B. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual; Blackwell Publishing Professional: Ames, IA, USA, 2006; p. 388. [Google Scholar]

- Prodi, A.; Purahong, W.; Tonti, S.; Salomoni, D.; Nipoti, P.; Covarelli, L.; Pisi, A. Difference in chemotype composition of Fusarium graminearum populations isolated from durum wheat in adjacent areas separated by the Apennines in Northern-Central Italy. J. Plant Pathol 2011, 27, 354–356. [Google Scholar]

- Brandfass, C.; Karlovsky, P. Upscaled CTAB-based DNA extraction and real-time PCR assays for Fusarium culmorum and F. graminearum DNA in plant material with reduced sampling error. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2008, 9, 2306–2321. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, P.; Simpson, D.; Weston, G.; Rezanoor, G.; Lees, A.; Parry, D.; Joyce, D. Detection and quantification of Fusarium culmorum and Fusarium graminearum in cereals using PCR assays. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol 1998, 53, 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P.; Fox, R.; Culham, A. Development of a PCR-based assay for rapid and reliable identification of pathogenic Fusariaum. Fems. Microbiol. Lett 2003, 218, 329–332. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, T.; O’Donnell, K. Morphological and molecular characterization of Fusarium pseudograminearum sp. nov., formerly recognized as the Group 1 population of F. graminearum. Mycologia 1999, 91, 597–609. [Google Scholar]

- Mule, G.; Susca, A.; Stea, G.; Moretti, A. Species-specific PCR assay based on the calmodulin partial gene for identification of Fusarium verticillioides, F. proliferatum and F. subglutinans. Eur. J. Plant Pathol 2004, 110, 495–502. [Google Scholar]

- Adejumo, T.O.; Hettwer, U.; Karlovsky, P. Survey of maize from south-western Nigeria for zearalenone, α- and β-zearalenols, fumonisin B1 and enniatins produced by Fusarium species. Food Addit. Contam 2007, 24, 993–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Klötzel, M.; Lauber, U.; Humpf, H.U. A new solid phase extraction clean-up method for the determination of 12 type A and B trichothecenes in cereals and cereal-based food by LC-MS/MS. Mol. Nutr. Food Res 2006, 50, 261–269. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, P.H.; Nielsen, K.F.; Ghorbani, F.; Spliid, N.H.; Nielsen, G.C.; Jørgensen, L.N. Occurrence of different trichothecenes and deoxynivalenol-3-β-D-glucoside in naturally and artificially contaminated Danish cereal grains and whole maize plants. Mycotoxin Res 2012, 28, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

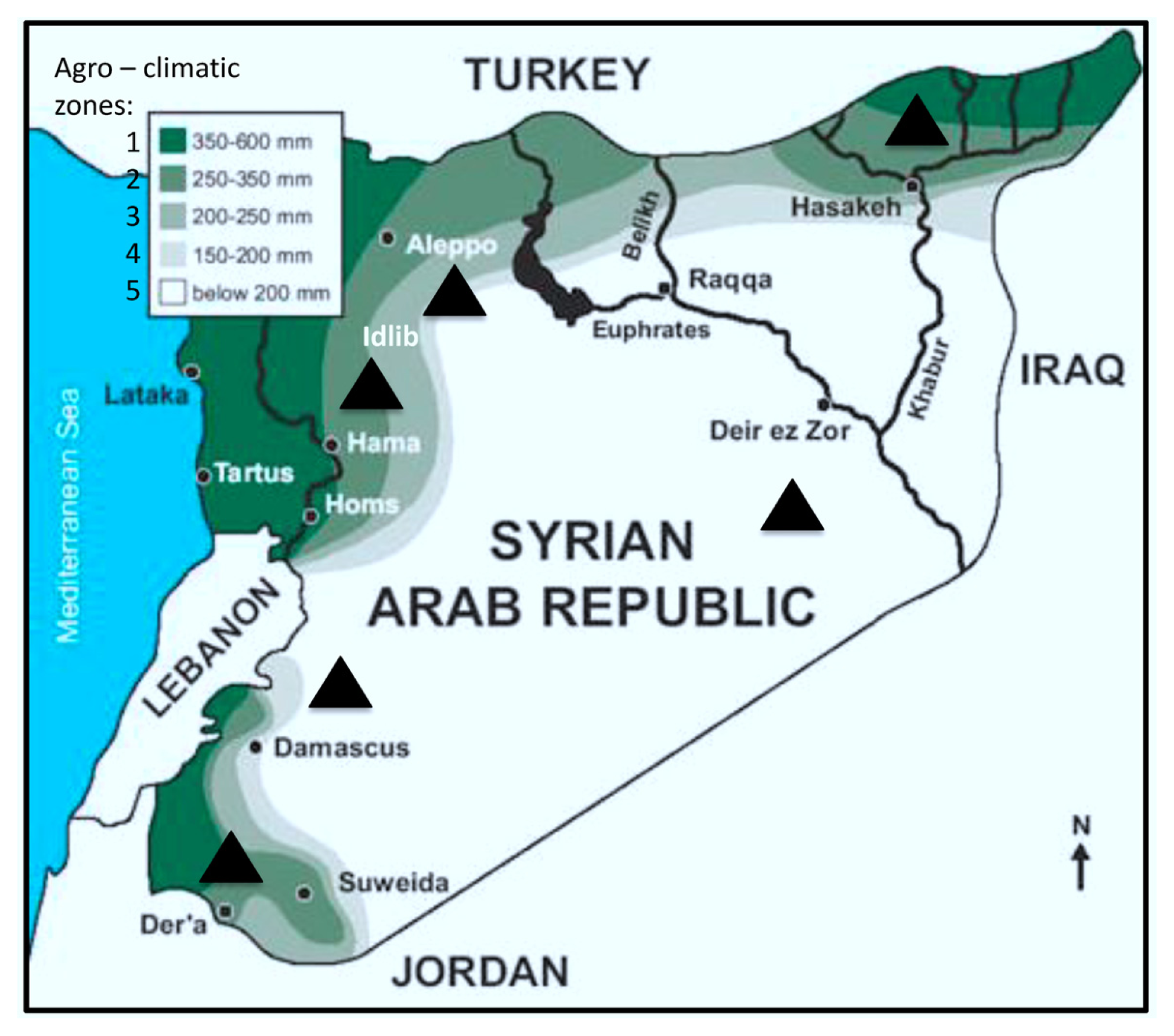

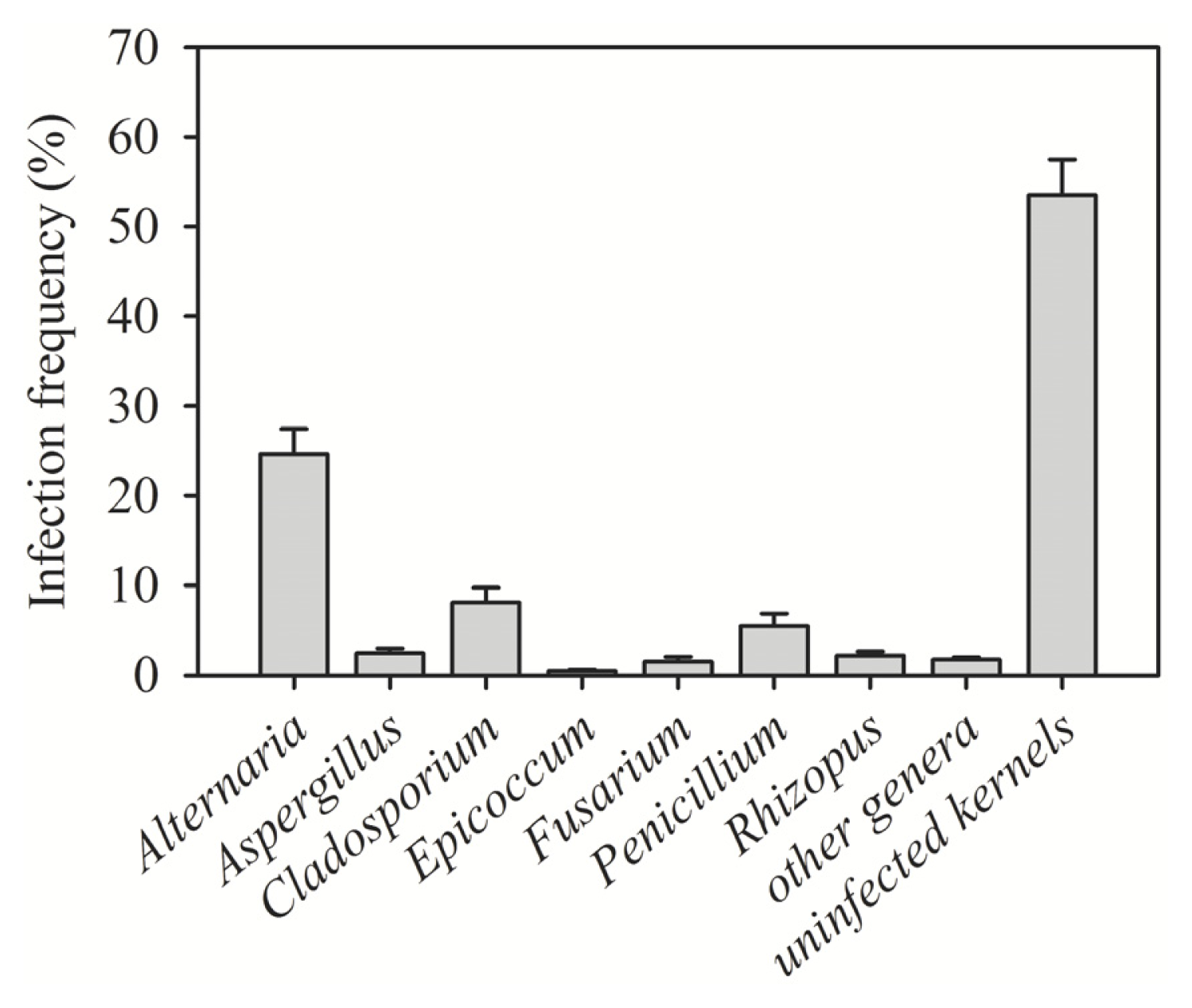

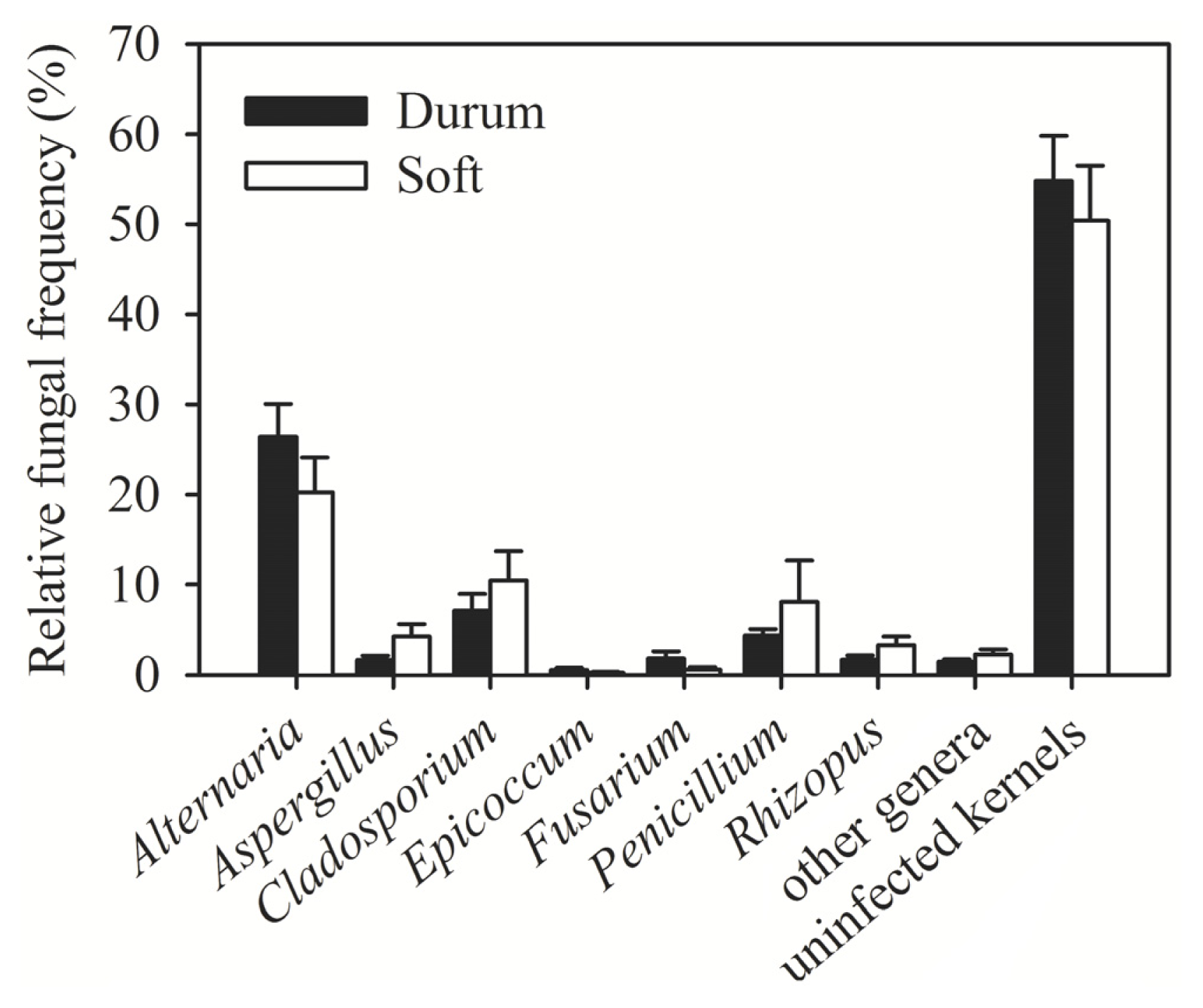

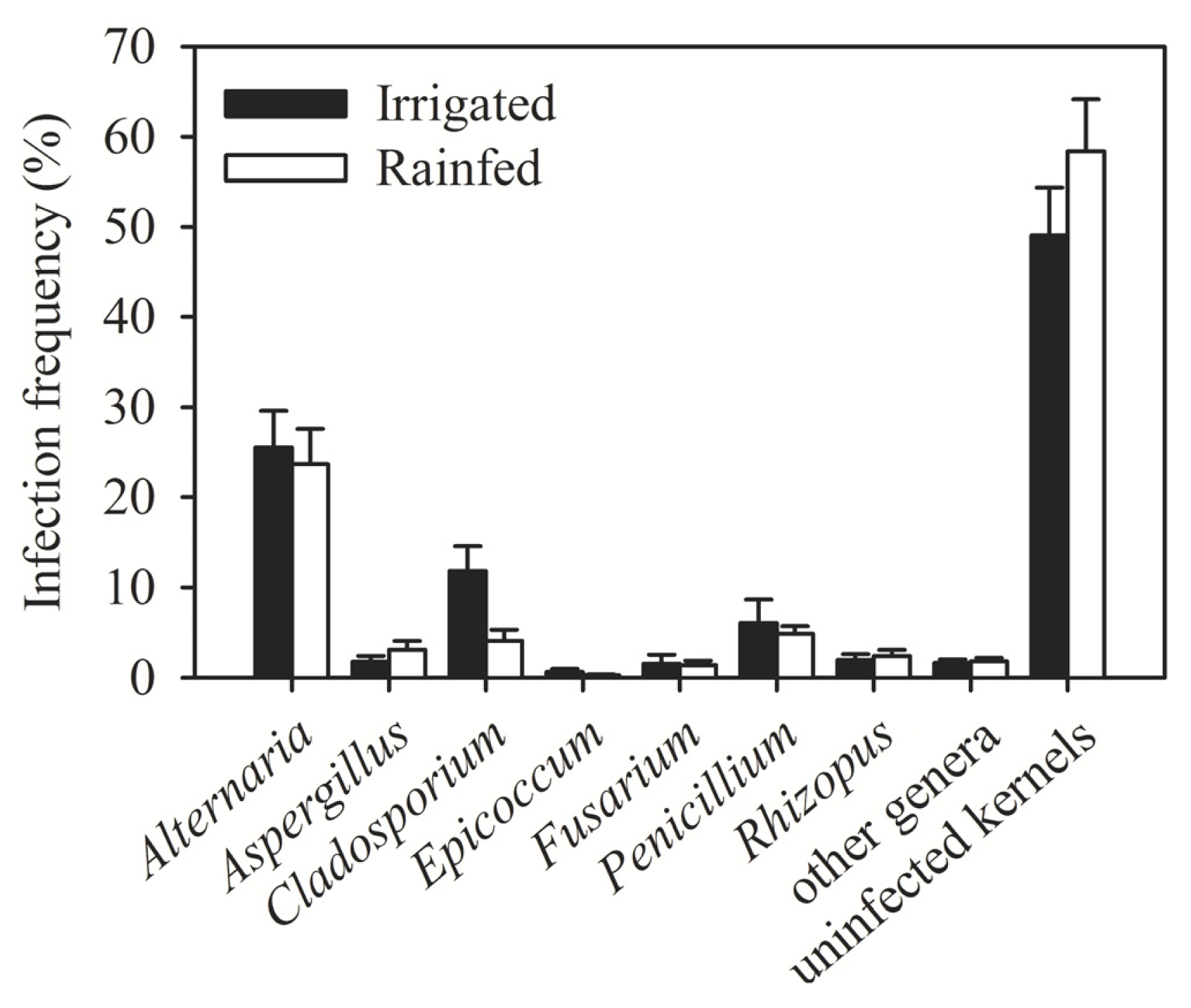

| Region (year) | Irrigated/rainfed | Number of samples | Number of kernels assayed | Alternaria (%) | Cladosporium (%) | Penicillium (%) | Aspergillus (%) | Epicoccum (%) | Rhizopus (%) | Fusarium (%) | Other genera (%) | Uninfected kernels (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Hassakeh (2009) | Rainfed | 7 | 2800 | 36.56 | 8.02 | 6.89 | 5.11 | 0.46 | 3.28 | 1.91 | 2.78 | 35.00 |

| Daraa 1 (2009) | Rainfed | 4 | 1600 | 25.35 | 0.38 | 3.94 | 3.90 | 0.06 | 0.63 | 3.08 | 1.56 | 61.10 |

| Daraa 2 (2009) | Irrigated | 1 | 400 | 3.00 | 0 | 1.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.30 | 1.00 | 94.00 |

| Daraa 1 (2010) | Rainfed | 1 | 400 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 8.00 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 2.00 | 0 | 89.00 |

| Dam. rural 1 (2009) | Rainfed | 1 | 400 | 12.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 0 | 8.00 | 0 | 0 | 75.00 |

| Dam. rural 2 (2009) | Irrigated | 4 | 1600 | 12.31 | 1.67 | 1.67 | 2.38 | 0.75 | 1.13 | 1.40 | 1.08 | 77.63 |

| Dam. rural 1 (2010) | Rainfed | 6 | 2400 | 15.04 | 3.71 | 4.58 | 2.71 | 0 | 3.13 | 0.04 | 2.17 | 68.63 |

| Dam. rural 2 (2010) | Irrigated | 8 | 3200 | 20.25 | 2.91 | 10.63 | 3.47 | 1.00 | 2.88 | 3.41 | 1.44 | 54.03 |

| Aleppo 1 (2009) | Rainfed | 3 | 1200 | 26.11 | 3.71 | 2.84 | 0 | 0.82 | 0 | 1.24 | 0.76 | 64.51 |

| Aleppo 2 (2009) | Irrigated | 1 | 400 | 35.00 | 11.00 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 42.00 |

| Idlib (2009) | Rainfed | 1 | 400 | 6.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 0 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 0 | 84.00 |

| Deir Ezzor (2010) | Irrigated | 11 | 4400 | 35.36 | 23.14 | 1.60 | 0.57 | 0.39 | 1.10 | 0.39 | 1.93 | 31.52 |

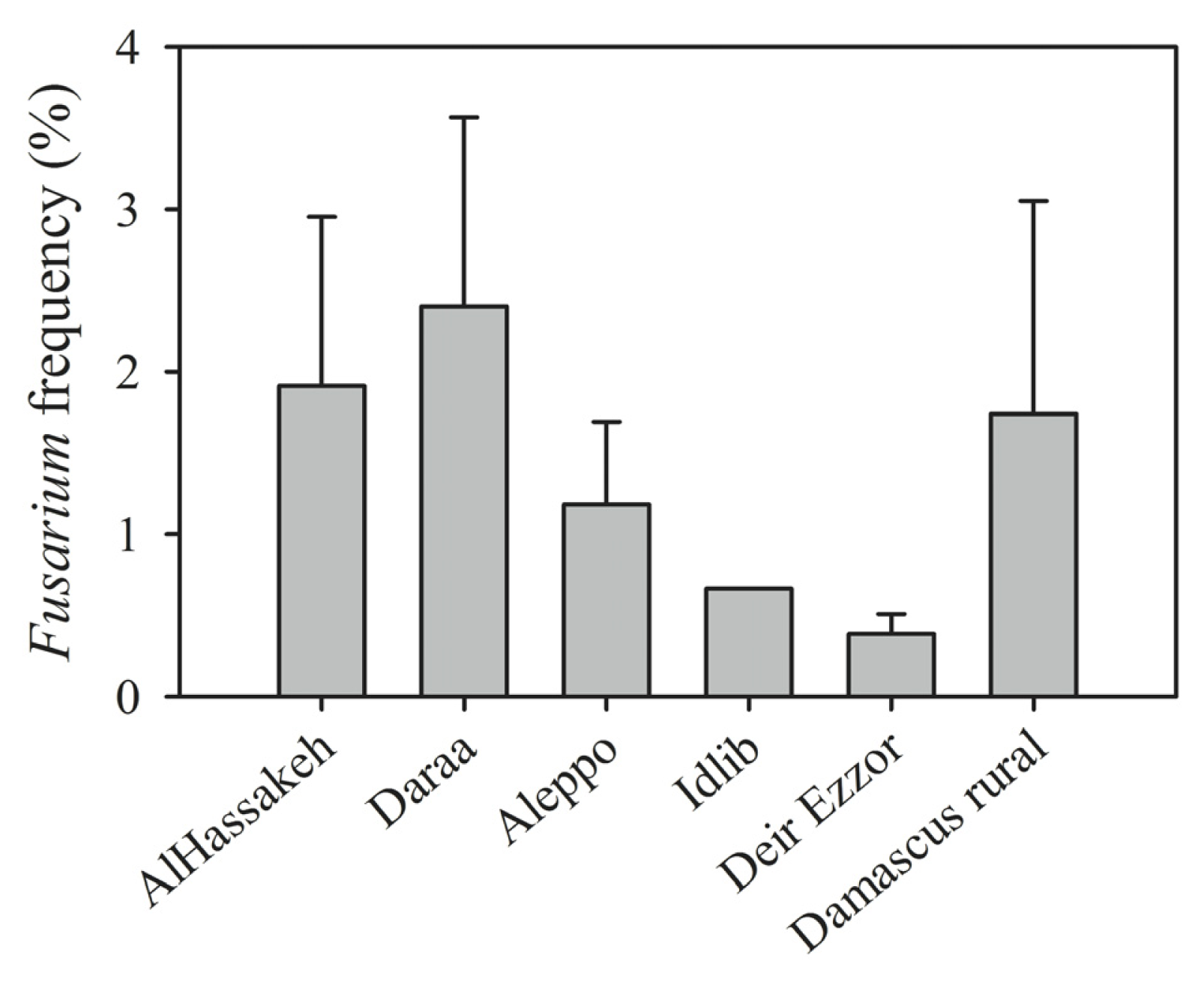

| Provinces | Total number of samples | Number of Fusarium infected samples | Fusarium species found (N. of isolates) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daraa | 6 | 5 | F. tricinctum (15), F. culmorum (13), F. equiseti (10) |

| Al-Hassakeh | 7 | 6 | F. tricinctum (26), F. culmorum (7), F. verticillioides (6), F. oxysporum (5), F. equiseti (4), F. semitectum (3), F. proliferatum (2) |

| Aleppo | 4 | 4 | F. verticillioides (6), F. proliferatum (6), F. tricinctum (2) |

| Idlib | 1 | 1 | F. tricinctum (1), F. verticillioides (1) |

| Deir Ezzor | 11 | 7 | F. graminearum (5) F. pseudograminearum (3), F. proliferatum (3), F. equiseti (2), F. culmorum (1), F. tricinctum (1), F. verticillioides (1) |

| Damascus rural | 19 | 7 | F. graminearum (16), F. culmorum (8), F. equiseti (7), F. tricinctum (4), F. verticillioides (3), F. proliferatum (2) |

| 100% | 62.5% |

| Fusarium species | Sample strain | Chemotype | Mycotoxins | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DON (μg/g) | 3Ac-DON (μg/g) | 15Ac-DON (μg/g) | NIV (μg/g) | Fus X (μg/g) | ZEN (μg/g) | |||

| F. culmorum | F960 | 3Ac-DON | >100 | 42.2 | 5.7 | - | - | 16.6 |

| F961 | 3Ac-DON | >100 | 9.0 | 1.7 | - | - | 7.7 | |

| F962 | 3Ac-DON | >100 | 9.6 | 1.6 | - | - | 17.9 | |

| F963 | NIV | 5.5 | - | - | >100 | 30.3 | 5.0 | |

| F965 | NIV | 9.4 | 0.5 | - | >100 | 52.7 | 0.1 | |

| F966 | 3Ac-DON | >100 | 48.1 | 6.3 | - | - | 1.8 | |

| F967 | NIV | 9.5 | 0.4 | - | >100 | >100 | 12.7 | |

| F968 | 3Ac-DON | >100 | 53.5 | 7.2 | - | - | 50.4 | |

| F969 | 3Ac-DON | >100 | 37.3 | 4.4 | - | - | 33.0 | |

| F970 | NIV | 7.6 | 0.2 | - | >100 | 51.8 | 0.6 | |

| F. graminearum | F1012 | NIV | - | - | - | 1.5 | 1.9 | 6.7 |

| F1014 | NIV | - | - | - | 1.5 | 1.5 | 6.2 | |

| F1016 | NIV | - | - | - | 1.6 | 1.8 | 4.0 | |

| F1017 | NIV | - | - | - | 2.9 | 3.0 | 6.0 | |

| F1018 | NIV | - | - | - | 2.1 | 1.7 | 4.5 | |

| F1022 | NIV | - | - | - | 2.9 | 2.4 | 3.3 | |

| F. pseudo-graminearum | F1029 | 2.6 | 10.3 | 1.0 | - | - | >100 | |

| F1030 | >100 | 64.8 | 8.0 | 1.3 | - | 0.8 | ||

| F. equiseti | F983 | - | - | - | - | - | - | <0.1 |

| F984 | Tri5 gene | - | - | - | 18.6 | - | 13.0 | |

| F985 | Tri5 gene | - | - | - | - | - | >100 | |

| F990 | Tri5 gene | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| F991 | Tri5 gene | - | - | - | 0.6 | 0.6 | <0.1 | |

| F992 | Tri5 gene | - | - | - | - | - | <0.1 | |

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Alkadri, D.; Nipoti, P.; Döll, K.; Karlovsky, P.; Prodi, A.; Pisi, A. Study of Fungal Colonization of Wheat Kernels in Syria with a Focus on Fusarium Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 5938-5951. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14035938

Alkadri D, Nipoti P, Döll K, Karlovsky P, Prodi A, Pisi A. Study of Fungal Colonization of Wheat Kernels in Syria with a Focus on Fusarium Species. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013; 14(3):5938-5951. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14035938

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlkadri, Dima, Paola Nipoti, Katharina Döll, Petr Karlovsky, Antonio Prodi, and Annamaria Pisi. 2013. "Study of Fungal Colonization of Wheat Kernels in Syria with a Focus on Fusarium Species" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 3: 5938-5951. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14035938