Magnetic Drug Targeting Reduces the Chemotherapeutic Burden on Circulating Leukocytes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

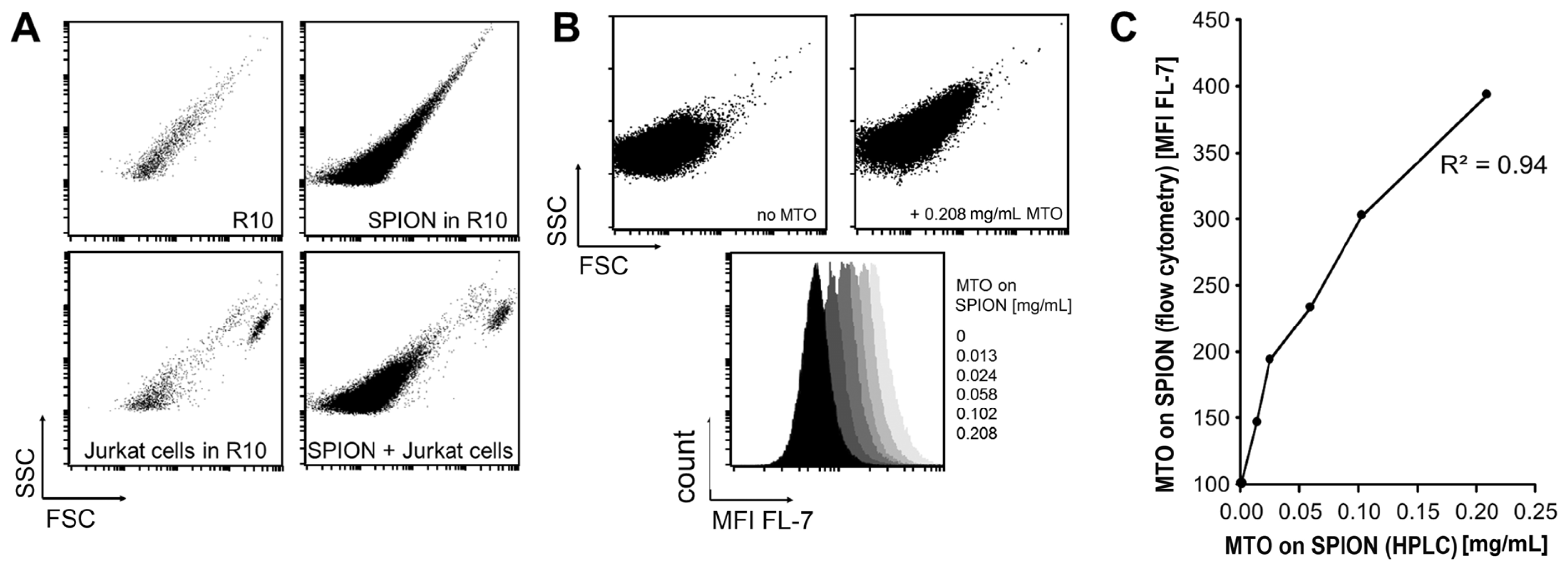

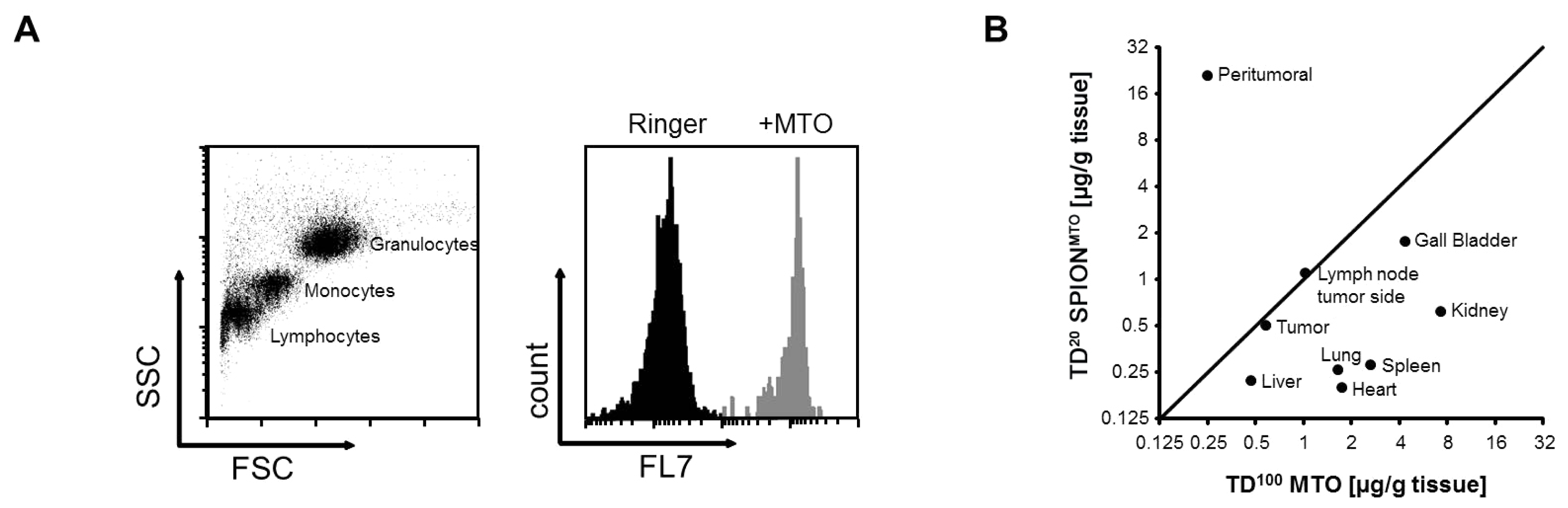

2.1. Analysis of SPION by Flow Cytometry

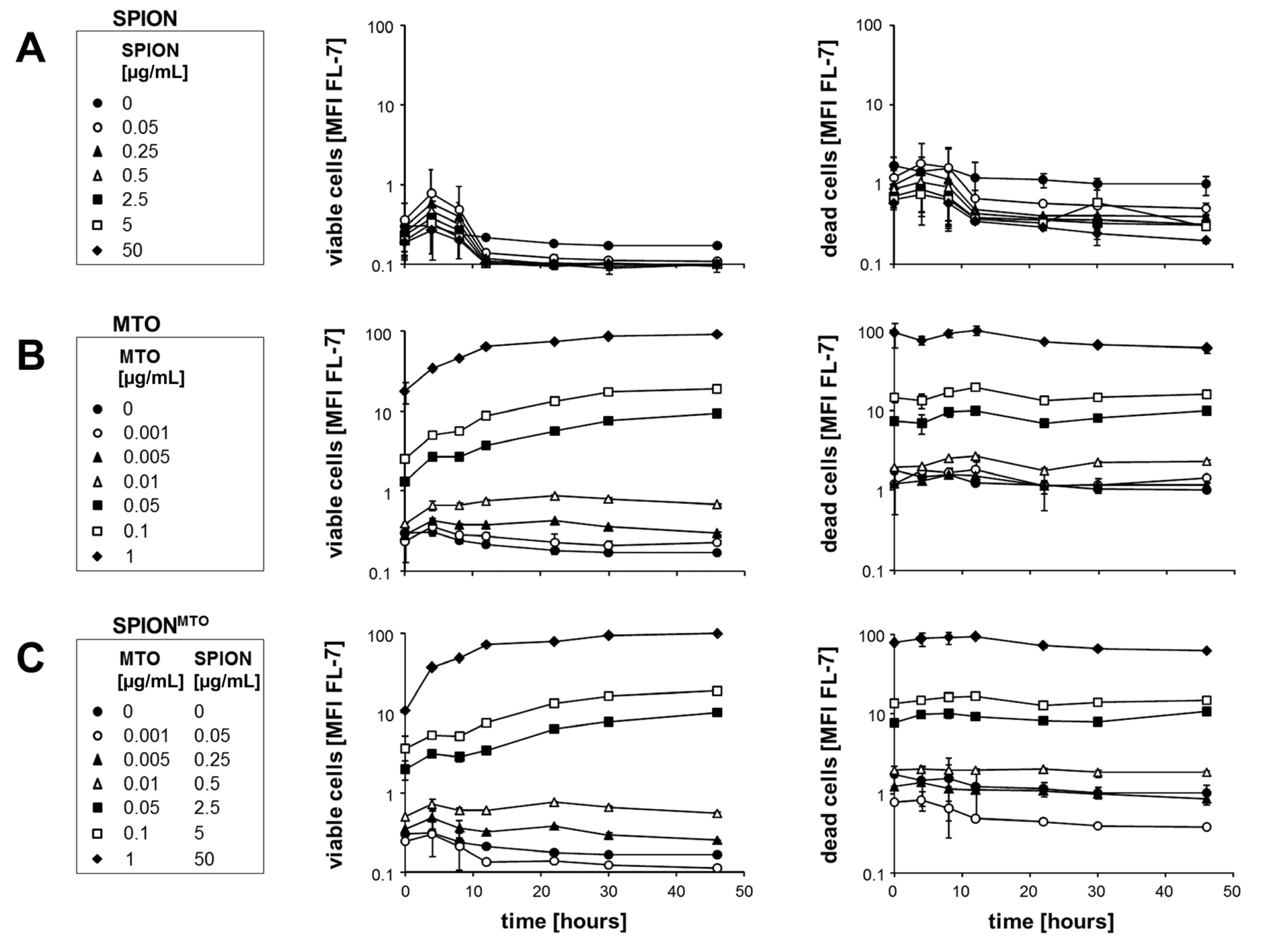

2.2. Uptake of MTO and SPIONMTO by Jurkat Cells

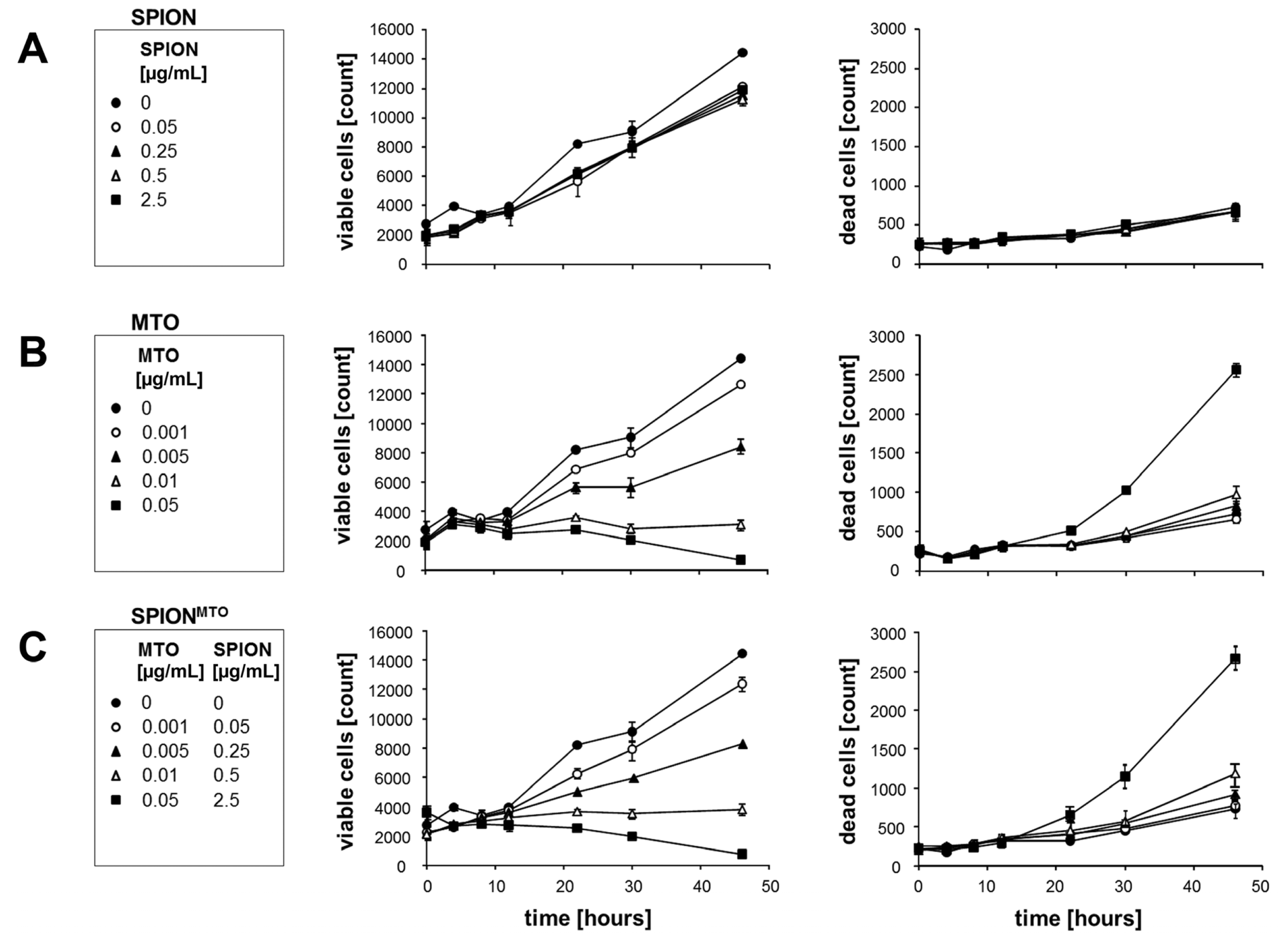

2.3. Proliferation of Jurkat Cells Treated with SPION, MTO and SPIONMTO

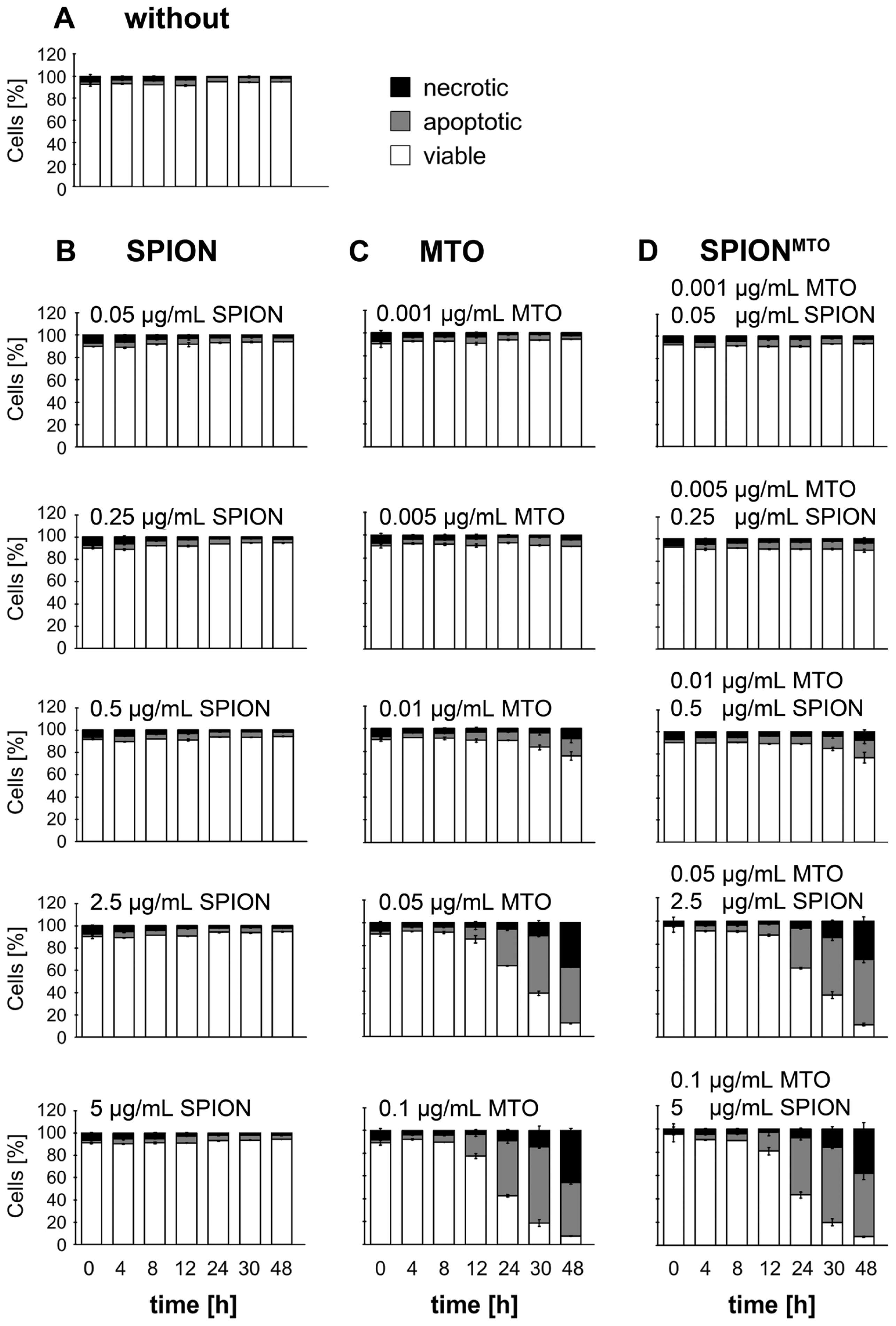

2.4. Apoptosis and Necrosis of Jurkat Cells Treated with SPION, MTO and SPIONMTO

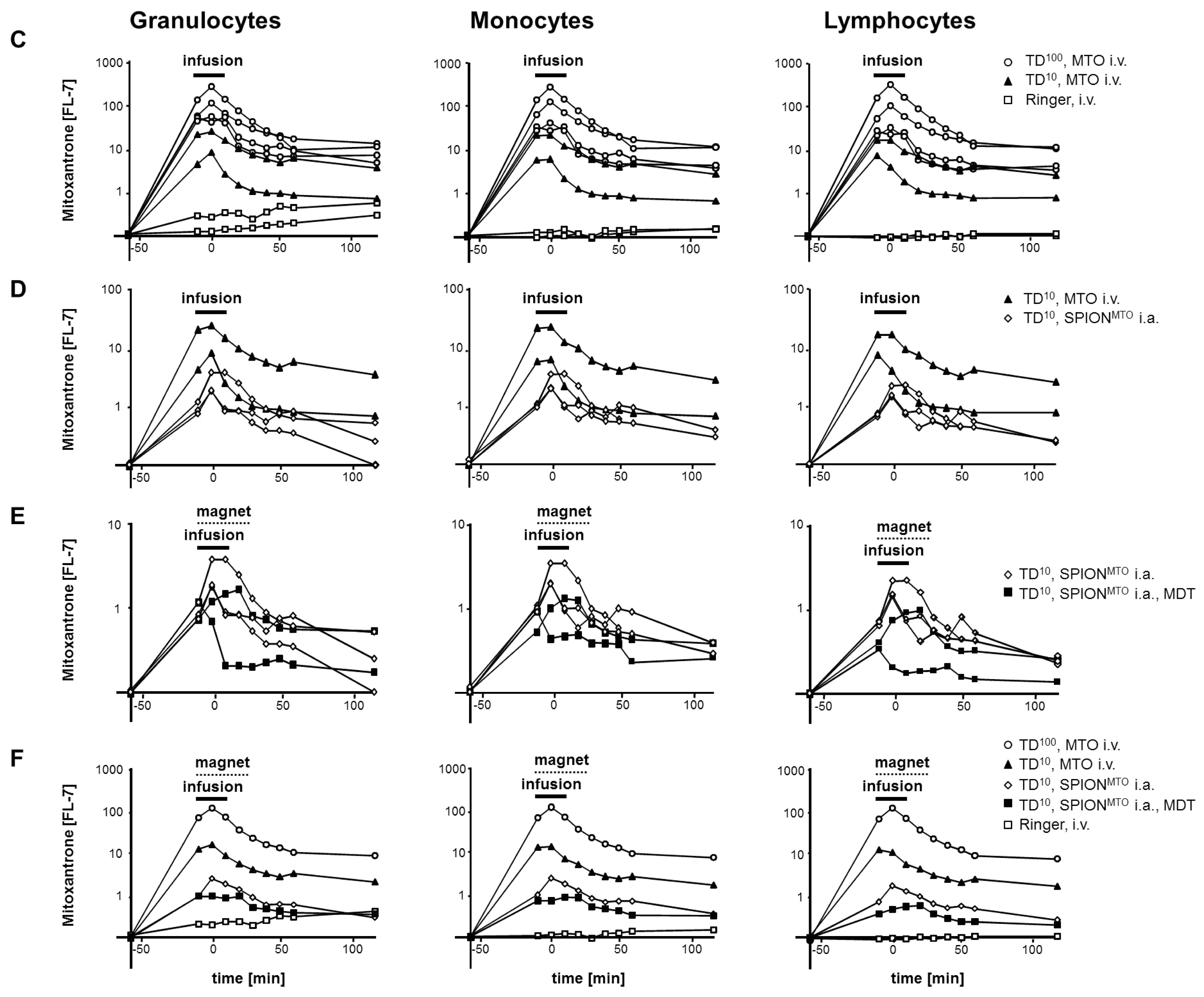

2.5. MDT Reduced the MTO Load of Circulating Leukocytes in Vivo

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Tumor Model

3.2. Chemotherapeutic Agent

3.3. Nanoparticles

3.4. Mode of Administration

3.5. Cells and Culture Conditions

3.6. Measurement of Cellular Morphology

3.7. Detection of Exposed Cell Phosphatidylserine and Analysis of Membrane Integrity

3.8. Flow Cytometry

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Shimizu, K; Oku, N. Cancer anti-angiogenic therapy. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 27, 599–605. [Google Scholar]

- Tietze, R; Lyer, S; Durr, S; Alexiou, C. Nanoparticles for cancer therapy using magnetic forces. Nanomedicine (London, England) 2012, 7, 447–457. [Google Scholar]

- Durr, S; Tietze, R; Lyer, S; Alexiou, C. Nanomedicine in otorhinolaryngology—Future prospects. Laryngorhinootologie 2012, 91, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiou, C; Tietze, R; Schreiber, E; Lyer, S. Nanomedicine: Magnetic nanoparticles for drug delivery and hyperthermia—new chances for cancer therapy. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2010, 53, 839–845. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiou, C; Jurgons, R; Schmid, R; Erhardt, W; Parak, F; Bergemann, C; Iro, H. Magnetic drug targeting—a new approach in locoregional tumor therapy with chemotherapeutic agents. Experimental animal studies. HNO 2005, 53, 618–622. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiou, C; Arnold, W; Klein, R.J; Parak, F.G; Hulin, P; Bergemann, C; Erhardt, W; Wagenpfeil, S; Lubbe, A.S. Locoregional cancer treatment with magnetic drug targeting. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 6641–6648. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, M.E; Smith, P.J. Long-term inhibition of DNA synthesis and the persistence of trapped topoisomerase II complexes in determining the toxicity of the antitumor DNA intercalators mAMSA and mitoxantrone. Cancer Res. 1990, 50, 5813–5818. [Google Scholar]

- Ballestrero, A; Ferrando, F; Garuti, A; Basta, P; Gonella, R; Esposito, M; Vannozzi, M.O; Sorice, G; Friedman, D; Puglisi, M.; et al. High-dose mitoxantrone with peripheral blood progenitor cell rescue: Toxicity, pharmacokinetics and implications for dosage and schedule. Br. J. Cancer 1997, 76, 797–804. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, G.P; Bruce, A.T; Ikeda, H; Old, L.J; Schreiber, R.D. Cancer immunoediting: From immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat. Immunol. 2002, 3, 991–998. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.M; Wolchok, J.D; Old, L.J. Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 278–287. [Google Scholar]

- Palucka, K; Ueno, H; Banchereau, J. Recent developments in cancer vaccines. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 1325–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, B; Rubner, Y; Wunderlich, R; Weiss, E.M; Pockley, A.G; Fietkau, R; Gaipl, U.S. Induction of abscopal anti-tumor immunity and immunogenic tumor cell death by ionizing irradiation - implications for cancer therapies. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 1751–1764. [Google Scholar]

- Kapuscinski, J; Darzynkiewicz, Z; Traganos, F; Melamed, M.R. Interactions of a new antitumor agent, 1,4-dihydroxy-5,8-bis[[2-[(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-ethyl]amino]-9,10-anthracenedion e, with nucleic acids. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1981, 30, 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, P; Novak, R.F. Mitoxantrone and bisantrene inhibition of platelet aggregation and prostaglandin E2 production in vitro. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1985, 34, 3609–3614. [Google Scholar]

- Khalafalla, S.E; Reimers, G.W. Preparation of dilution-stable aqueous magnetic fluids. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1980, 16, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Tietze, R; Schreiber, E; Lyer, S; Alexiou, C. Mitoxantrone loaded superparamagnetic nanoparticles for drug targeting: A versatile and sensitive method for quantification of drug enrichment in rabbit tissues using HPLC-UV. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 597304:1–597304:8. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiou, C; Diehl, D; Henninger, P; Iro, H; Rockelein, R; Schmidt, W; Weber, H. A high field gradient magnet for magnetic drug targeting. IEEE Trans Appl. Supercon. 2006, 16, 1527–1530. [Google Scholar]

- Elstein, K.H; Zucker, R.M. Comparison of cellular and nuclear flow cytometric techniques for discriminating apoptotic subpopulations. Exp. Cell Res. 1994, 211, 322–331. [Google Scholar]

- Hagenhofer, M; Germaier, H; Hohenadl, C; Rohwer, P; Kalden, J.R; Herrmann, M. UV-B irradiated cell lines execute programmed cell death in various forms. Apoptosis 1998, 3, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Vermes, I; Haanen, C; Steffens-Nakken, H; Reutelingsperger, C. A novel assay for apoptosis. Flow cytometric detection of phosphatidylserine expression on early apoptotic cells using fluorescein labelled Annexin V. J. Immunol. Methods 1995, 184, 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.J; Sykes, H.R; Fox, M.E; Furlong, I.J. Subcellular distribution of the anticancer drug mitoxantrone in human and drug-resistant murine cells analyzed by flow cytometry and confocal microscopy and its relationship to the induction of DNA damage. Cancer Res. 1992, 52, 4000–4008. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A; Weilbach, F.X; Toyka, K.V; Gold, R. Mitoxantrone induces cell death in peripheral blood leucocytes of multiple sclerosis patients. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2005, 139, 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Durr, S; Lyer, S; Mann, J; Janko, C; Tietze, R; Schreiber, E; Herrmann, M; Alexiou, C. Real-time cell analysis of human cancer cell lines after chemotherapy with functionalized magnetic nanoparticles. Anticancer Res. 2012, 32, 1983–1989. [Google Scholar]

- Apetoh, L; Ghiringhelli, F; Tesniere, A; Obeid, M; Ortiz, C; Criollo, A; Mignot, G; Maiuri, M.C; Ullrich, E; Saulnier, P.; et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Zitvogel, L; Apetoh, L; Ghiringhelli, F; Andre, F; Tesniere, A; Kroemer, G. The anticancer immune response: Indispensable for therapeutic success? J. Clin. Invest. 2008, 118, 1991–2001. [Google Scholar]

- Apetoh, L; Mignot, G; Panaretakis, T; Kroemer, G; Zitvogel, L. Immunogenicity of anthracyclines: Moving towards more personalized medicine. Trends Mol. Med. 2008, 14, 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi, L; Senovilla, L; Zitvogel, L; Kroemer, G. The secret ally: Immunostimulation by anticancer drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 215–233. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C; Han, Y; Ren, Y; Wang, Y. Mitoxantrone-mediated apoptotic B16-F1 cells induce specific anti-tumor immune response. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2009, 6, 469–475. [Google Scholar]

- Zolnik, B.S; Gonzalez-Fernandez, A; Sadrieh, N; Dobrovolskaia, M.A. Nanoparticles and the immune system. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 458–465. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunwale, B; Schmidt-Ott, A; Meek, R.M; Brewer, J.M. Investigating the immunologic effects of CoCr nanoparticles. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2009, 467, 3010–3016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.A; Jin, N; Wang, J; Ding, J; Gao, C; Cheng, J; Xia, G; Gao, F; Zhou, Y; Chen, Y.; et al. The effect of magnetic nanoparticles of Fe3O4 on immune function in normal ICR mice. Int. J. Nanomed. 2010, 5, 593–599. [Google Scholar]

| MTO content (μg/g tissue) after treatment | ||

|---|---|---|

| Organ | Conventional chemotherapy (TD100 MTO) | Magnetic drug targeting (TD20 SPIONMTO) |

| Tumor | 0.58 | 0.50 |

| Peritumoral | 0.25 | 20.93 |

| Ipsilateral lymph node | 1.03 | 1.05 |

| Heart | 1.75 | 0.20 |

| Lung | 1.66 | 0.26 |

| Liver | 0.47 | 0.22 |

| Gall bladder | 4.38 | 1.75 |

| Kidney | 7.29 | 0.62 |

| Spleen | 2.65 | 0.28 |

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Janko, C.; Dürr, S.; Munoz, L.E.; Lyer, S.; Chaurio, R.; Tietze, R.; Löhneysen, S.V.; Schorn, C.; Herrmann, M.; Alexiou, C. Magnetic Drug Targeting Reduces the Chemotherapeutic Burden on Circulating Leukocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 7341-7355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14047341

Janko C, Dürr S, Munoz LE, Lyer S, Chaurio R, Tietze R, Löhneysen SV, Schorn C, Herrmann M, Alexiou C. Magnetic Drug Targeting Reduces the Chemotherapeutic Burden on Circulating Leukocytes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013; 14(4):7341-7355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14047341

Chicago/Turabian StyleJanko, Christina, Stephan Dürr, Luis E. Munoz, Stefan Lyer, Ricardo Chaurio, Rainer Tietze, Sarah Von Löhneysen, Christine Schorn, Martin Herrmann, and Christoph Alexiou. 2013. "Magnetic Drug Targeting Reduces the Chemotherapeutic Burden on Circulating Leukocytes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 4: 7341-7355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14047341