Mechanisms of Enzyme-Catalyzed Reduction of Two Carcinogenic Nitro-Aromatics, 3-Nitrobenzanthrone and Aristolochic Acid I: Experimental and Theoretical Approaches

Abstract

:1. Introduction

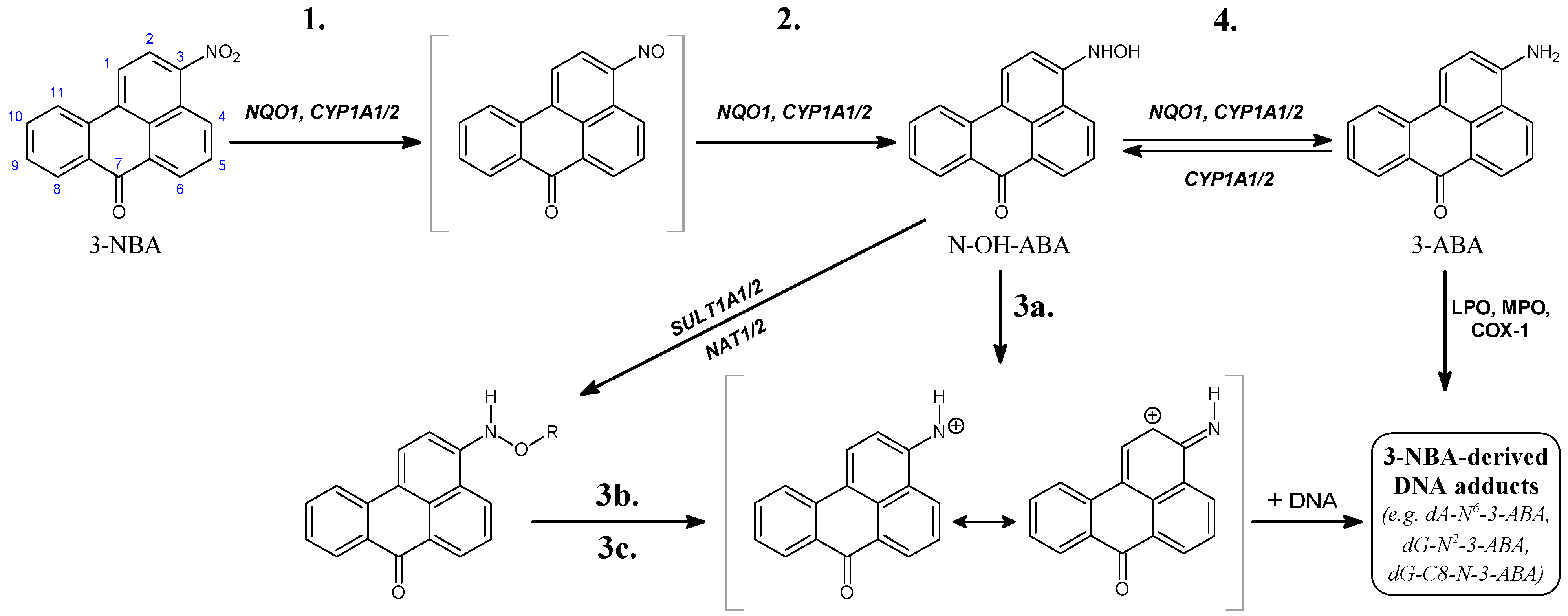

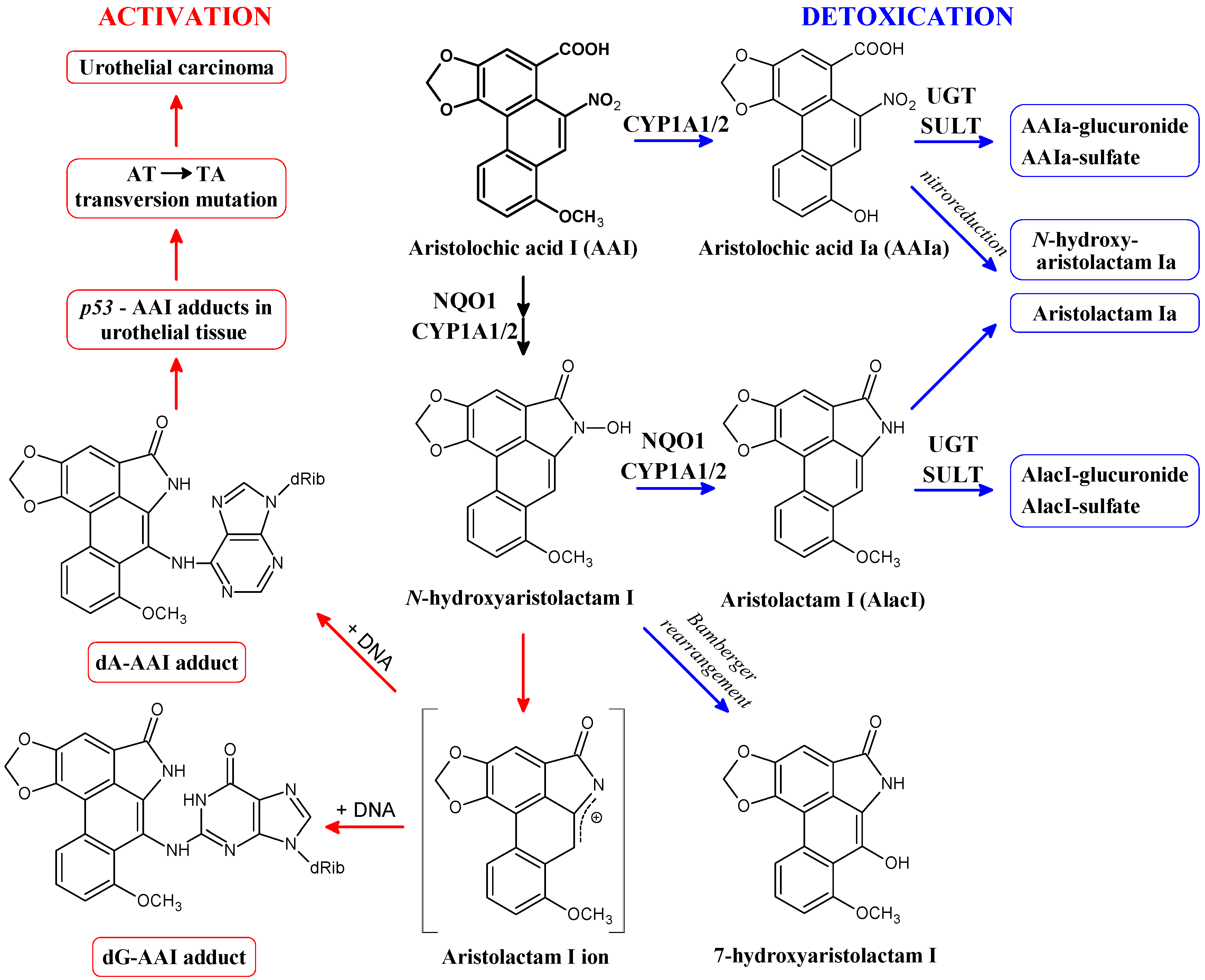

2. Cytosolic NAD(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase (NQO1) and Microsomal Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A1 and 1A2 Enzymes Reductively Activate 3-NBA and AAI

2.1. Reductive Activation of 3-NBA and Aristolochic Acid I (AAI) by Human NQO1

2.2. Participation of Conjugation Enzymes in Activation of 3-NBA and AAI

| Enzymatic System | Total Levels of DNA Adducts in RAL a (Mean ± SD/108 Nucleotides) | |

|---|---|---|

| 3-NBA | AAI | |

| NQO1 + NADPH | 10 ± 2 | 15 ± 2 |

| NQO1 + NADPH + dicoumarol | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.4 ± 0.04 |

| NQO1 + NADPH + SULT1A1 + PAPS b | 16 ± 2 | 15 ± 2 |

| NQO1 + NADPH + SULT1A2 + PAPS | 36 ± 2 | 16 ± 2 |

| NQO1 + NADPH + NAT1 + acetyl-CoA c | 16 ± 2 | 15 ± 2 |

| NQO1 + NADPH + NAT2 + acetyl-CoA | 1720 ± 50 | 17 ± 2 |

2.3. Reductive Activation of 3-NBA and AAI by Human CYP1A1 and 1A2

| Enzymatic System | Total Levels of DNA Adducts in RAL a (Mean ± SD/108 Nucleotides) | |

|---|---|---|

| 3-NBA | AAI | |

| POR + NADPH | 10 ± 2 | 15 ± 2 |

| CYP1A1 + POR + NADPH | 52 ± 5 | 84 ± 7 |

| CYP1A2 + POR + NADPH | 48 ± 5 | 126 ± 12 |

| CYP1B1 + POR + NADPH | 5 ± 1 | 11 ± 1 |

3. Calculation of 3-NBA and AAI Reduction, Heterolytic Cleavage of 3-NBA and AAI N-Hydroxyl Derivatives and Their Sulfate or Acetate Conjugates—Thermodynamic Approaches

| (A) |  [kcal/mol] a [kcal/mol] a | |||||

| Reaction step (Figure 1) solvation model | 1. | 2. | 3a. | 3b. | 3c. | 4. |

| NO2 → NO | NO → NHOH | NHOH → NH+ + OH− | NHOAc → NH+ + Ac− | NHOSO3− → NH+ + SO42− | NHOH → NH2 | |

| CPCM | −46.9 | −28.3 | 22.3 | −6.1 | −8.3 | −64.5 |

| LD | −44.0 | −27.0 | −4.5 | −22.3 | −24.8 | −67.7 |

| (B) |  [kcal/mol] a [kcal/mol] a | |||||

| Reaction step (Figure 3) solvation model | 1. | 2 + 3. | 4a. | 4b. | 4c. | 5. |

| NO2 → NO | NO → N-OH-lact + OH− | N-OH-lact → N-lact+ + OH− | N-OAc-lact → N-lact+ + Ac− | N-OSO3−-lact → N-lact+ + SO42− | N-OH-lact → N-lact + H2O | |

| CPCM | −46.7 | −19.1 | 30.6 | 0.6 | −4.9 | −70.7 |

| LD | −40.4 | −9.1 | −7.1 | −29.4 | −24.6 | −69.8 |

= −4.5 kcal/mol), which implies that it requires conjugation to decompose efficiently to the cation (see Table 3), the reaction free energy of dissociation of N-hydroxyaristolactam I found by the LD approach is −7.1 kcal/mol, which is 2.6 kcal/mol lower than for the N-hydroxylamine derivative of 3-NBA (Table 3; reaction step 3a for 3-NBA reduction and 4a for AAI reduction). Hence, N-hydroxyaristolactam I decomposes spontaneously under the same conditions. This indicates that the N-O bond in N-hydroxyaristolactam I is less stable than in N-OH-3-ABA. Consequently, if the dissociation of the N-O bond is relatively fast, it is not the rate limiting step in AAI-DNA adduct formation and any conjugation reaction would not make dissociation faster and would not lead to a higher DNA adduct level. These findings indicate that the overall rate controlling step during AAI reductive activation is not the enzymatic conjugation followed by spontaneous formation of a cyclic cation, but rather the initial nitro reduction mediated by NQO1.

= −4.5 kcal/mol), which implies that it requires conjugation to decompose efficiently to the cation (see Table 3), the reaction free energy of dissociation of N-hydroxyaristolactam I found by the LD approach is −7.1 kcal/mol, which is 2.6 kcal/mol lower than for the N-hydroxylamine derivative of 3-NBA (Table 3; reaction step 3a for 3-NBA reduction and 4a for AAI reduction). Hence, N-hydroxyaristolactam I decomposes spontaneously under the same conditions. This indicates that the N-O bond in N-hydroxyaristolactam I is less stable than in N-OH-3-ABA. Consequently, if the dissociation of the N-O bond is relatively fast, it is not the rate limiting step in AAI-DNA adduct formation and any conjugation reaction would not make dissociation faster and would not lead to a higher DNA adduct level. These findings indicate that the overall rate controlling step during AAI reductive activation is not the enzymatic conjugation followed by spontaneous formation of a cyclic cation, but rather the initial nitro reduction mediated by NQO1.

4. Binding of 3-NBA and AAI to the Active Sites of NQO1 and CYP1A1/2 Enzymes

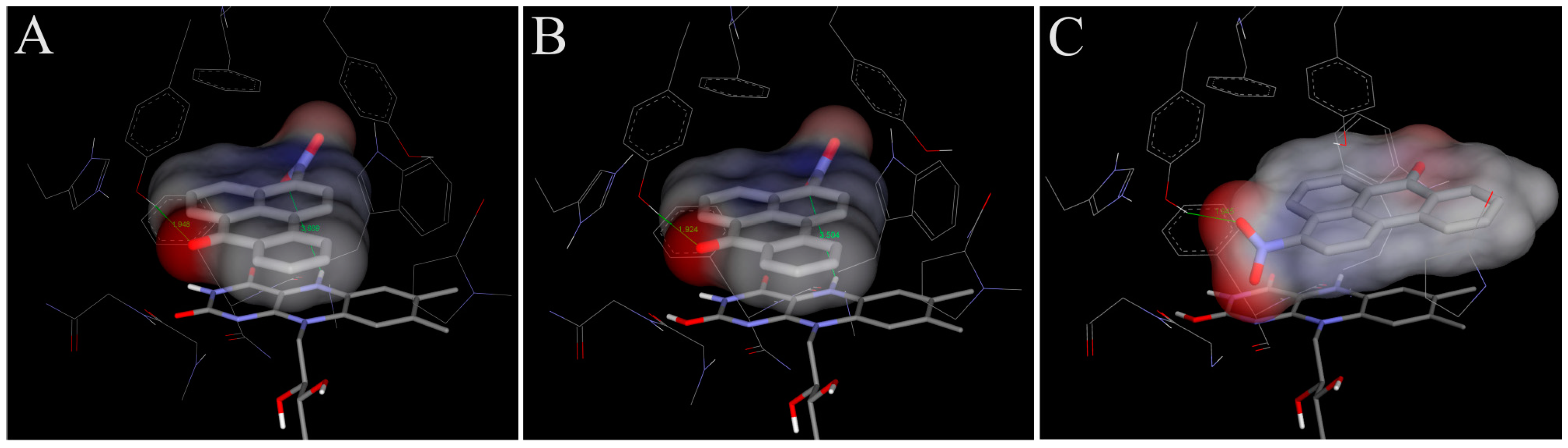

4.1. Binding of 3-NBA and AAI to the Active Site of NQO1

| NQO1 FADH− Deprotonated (Anionic Form) | NQO1 Enol-FADH2 (Protonated Form) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| direct H-transfer | direct H-transfer | mediated H-transfer (e−,H+,e−) | ||||

| Estimated Free Energy of binding [kcal/mol] | N5(FAD)-O(NBA/AAI) distance [Å] a | Estimated Free Energy of binding [kcal/mol] | N5(FAD)-O(NBA/AAI) distance [Å] a | Estimated Free Energy of binding [kcal/mol] | OH(Y128)-O(NBA/AAI) distance [Å] b | |

| 3-NBA | −5.7 | 3.7 | −5.7 | 3.5 | −6.2 | 3.1 |

| AAI | −6.4 | 3.2 | −6.3 | 3.2 | −7.9 | 2.8 |

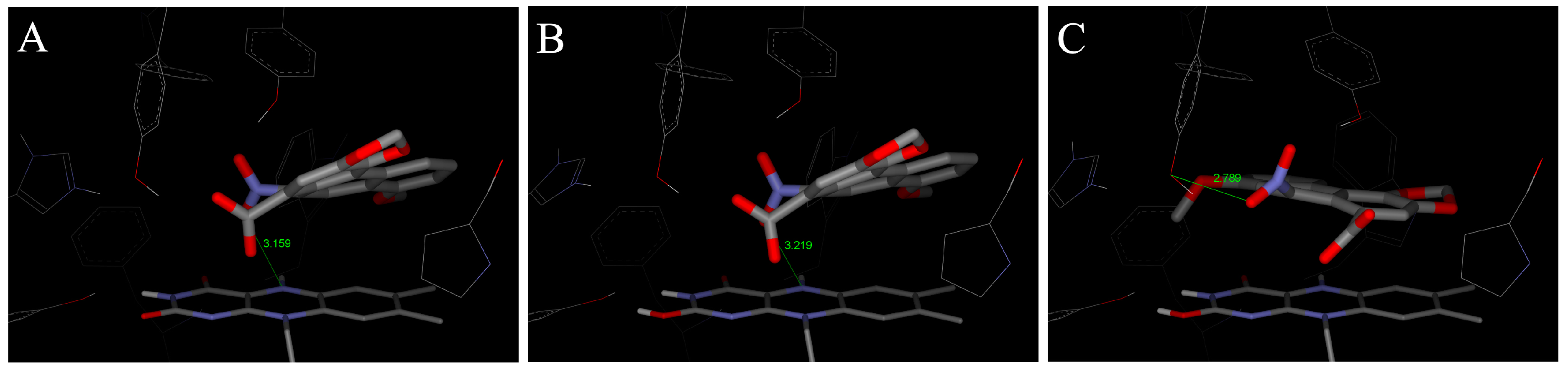

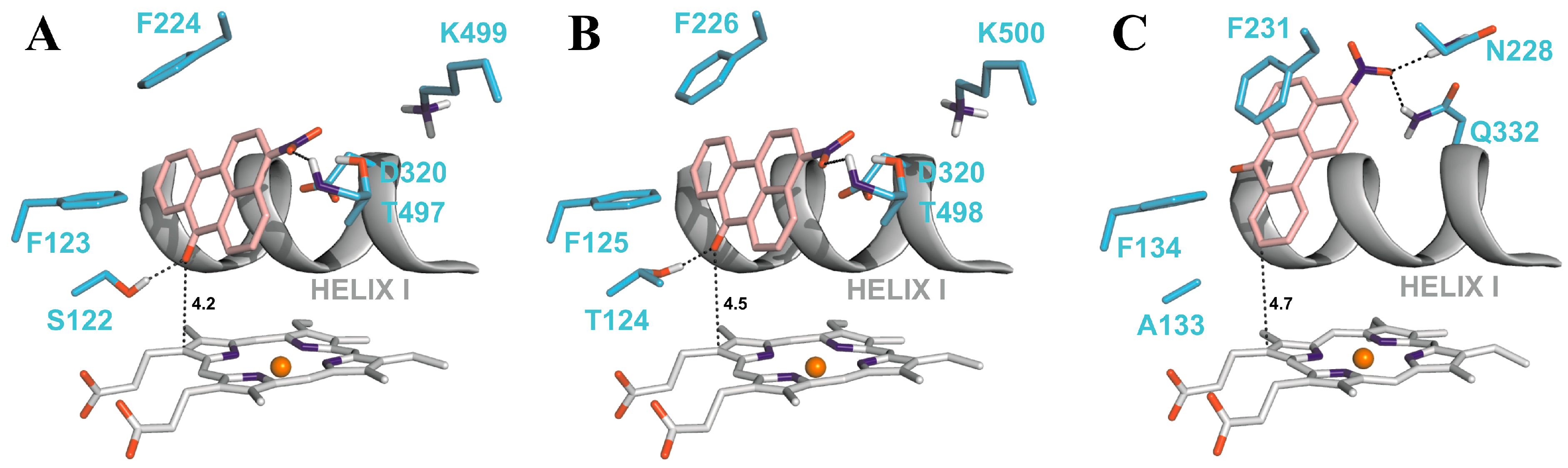

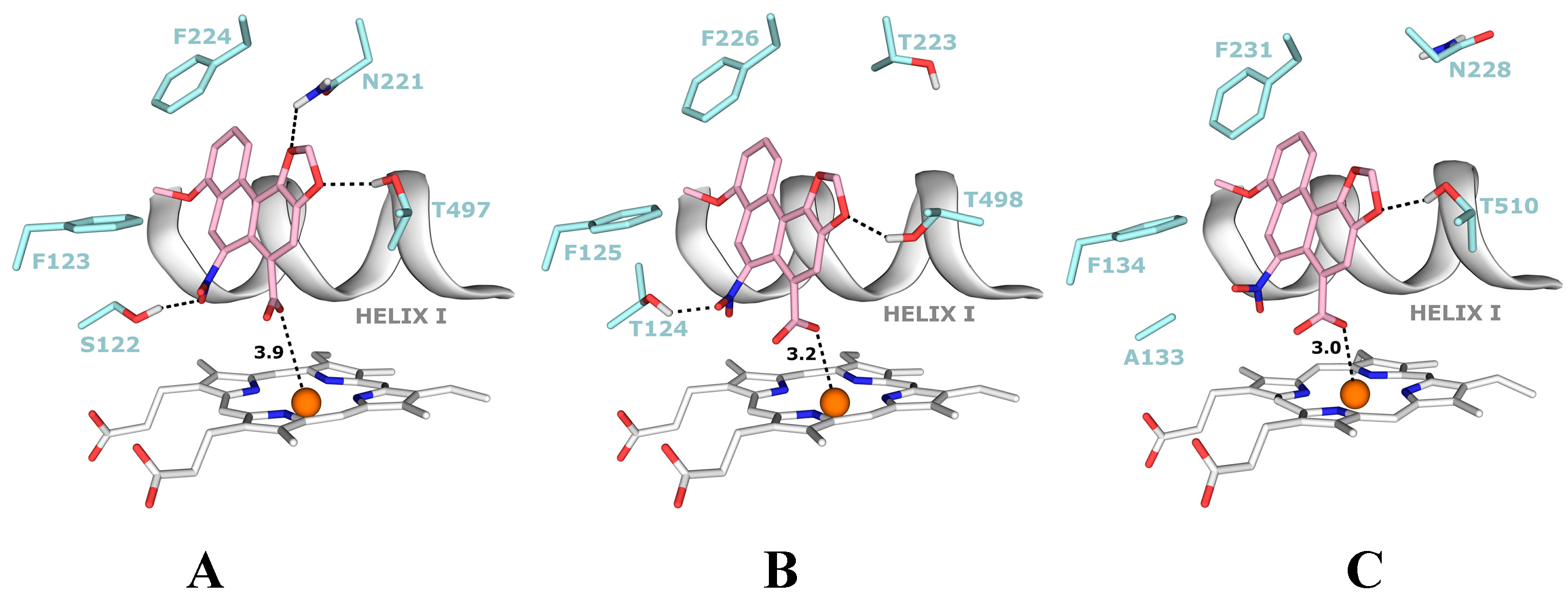

4.2. Binding of 3-NBA and AAI to the Active Sites of CYP1A1 and 1A2

| CYP1A1 | CYP1A2 | CYP1B1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Free Energy of binding [kcal/mol] | 3-NBA/AAI—heme distance [Å] a | Estimated Free Energy of binding [kcal/mol] | 3-NBA/AAI—heme distance [Å] a | Estimated Free Energy of binding [kcal/mol] | 3-NBA/AAI—heme distance [Å] a | |

| 3-NBA | −8.04 | 4.2 | −8.02 | 4.5 | −7.73 | 4.7 |

| AAI | −5.66 | 3.9 | −5.81 | 3.2 | −5.59 | 3.0 |

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Diesel and gasoline engine exhausts and some nitroarenes. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Diesel and gasoline engine exhausts and some nitroarenes. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS). Selected nitro- and nitro-oxy-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. In Environment Health Criteria Monographs; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tokiwa, H.; Ohnishi, Y. Mutagenicity and carcinogenicity of nitroarenes and their sources in the environment. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1986, 17, 23–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, K.; Jariyasopit, N.; Massey Simonich, S.L.; Tao, S.; Atkinson, R.; Arey, J. Formation of nitro-PAHs from the heterogeneous reaction of ambient particle-bound PAHs with N2O5/NO3/NO2. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 8434–4842. [Google Scholar]

- Arlt, V.M.; Glatt, H.; Gamboa da Costa, G.; Reynisson, J.; Takamura-Enya, T.; Phillips, D.H. Mutagenicity and DNA adduct formation by the urban air pollutant 2-nitrobenzanthrone. Toxicol. Sci. 2007, 98, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attfield, M.D.; Schleiff, P.L.; Lubin, J.H.; Blair, A.; Stewart, P.A.; Vermeulen, R.; Coble, J.B.; Silverman, D.T. The diesel exhaust in miners study: A cohort mortality study with emphasis on lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012, 104, 869–883. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D.T.; Samanic, C.M.; Lubin, J.H.; Blair, A.E.; Stewart, P.A.; Vermeulen, R.; Coble, J.B.; Rothman, N.; Schleiff, P.L.; Travis, W.D.; et al. The diesel exhaust in miners study: A nested case-control study of lung cancer and diesel exhaust. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012, 104, 855–868. [Google Scholar]

- Wiessler, M. DNA adducts of pyrrolizidine alkaloids, nitroimidazoles and aristolochic acid. IARC Sci. Publ. 1994, 125, 165–177. [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Some traditional herbal medicines, some mycotoxins, naphthalene and styrene. In Environment Health Criteria Monographs; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). A review of human CARCINOGENS: Pharmaceuticals. In Environ. Health Criteria Monographs; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Purohit, V.; Basu, A.K. Mutagenicity of nitroaromatic compounds. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2000, 3, 673–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enya, T.; Suzuki, H.; Watanabe, T.; Hirayama, T.; Hisamatsu, Y. 3-Nitrobenzanthrone, a powerful bacterial mutagen and suspected human carcinogen found in diesel exhausts and airborne particulates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1997, 31, 2772–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, A.; Dahmann, D.; Krekeler, H.; Jacob, J. Biomonitoring of polycyclic aromatic compounds in the urine of mining workers occupationally exposed to diesel exhaust. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2002, 204, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, V.M. 3-Nitrobenzanthrone, a potential human cancer hazard in diesel exhaust and urban air pollution: A review of the evidence. Mutagenesis 2005, 20, 399–410. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, E.; Zeisig, M.; Kawamura, K.; Hisumatsu, Y.; Sugeta, A.; Adachi, S; Moller, L. DNA-adduct and tumor formations in rats after intratracheal administration of the urban air pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone. Carcinogenesis 2005, 26, 1821–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynisson, J.; Stiborová, M.; Martínek, V.; Gamboa da Costa, G.; Phillips, D.H.; Arlt, V.M. Mutagenic potential of nitrenium ions of nitrobenzanthrones: Correlation between theory and experiment. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2008, 49, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieler, C.A.; Wiessler, M.; Erdinger, L.; Suzuki, H.; Enya, T.; Schmeiser, H.H. DNA adduct formation from the mutagenic air pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone. Mutat. Res. 1999, 439, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, V.M.; Bieler, C.A.; Mier, W.; Wiessler, M.; Schmeiser, H.H. DNA adduct formation by the ubiquitous environmental contaminant 3-nitrobenzanthrone in rats determined by 32P-postlabeling. Int. J. Cancer 2001, 93, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, V.M.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Osborne, M.R.; Kawanishi, M.; Kanno, T.; Yagi, T.; Phillips, D.H.; Takamura-Enya, T. Identification of three major DNA adducts formed by the carcinogenic air pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone in rat lung at the C8 and N2 position of guanine and at the N6 position of adenine. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 118, 2139–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, V.M.; Zhan, L.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Honma, M.; Hayashi, M.; Phillips, D.H.; Suzuki, T. DNA adducts and mutagenic specificity of the ubiquitous environmental pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone in Muta Mouse. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2004, 43, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, V.M.; Gingerich, J.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Phillips, D.H.; Douglas, G.R.; White, P.A. Genotoxicity of 3-nitrobenzanthrone and 3-aminobenzanthrone in Muta Mouse and lung epithelial cells derived from Muta Mouse. Mutagenesis 2008, 23, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vom Brocke, J.; Krais, A.; Whibley, C.; Hollstein, M.C.; Schmeiser, H.H. The carcinogenic air pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone induces GC to TA transversion mutations in human p53 sequences. Mutagenesis 2009, 24, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Vanherweghem, J.L.; Depierreux, M.; Tielemans, C.; Abramowicz, D.; Dratwa, M.; Jadoul, M.; Richard, C.; Valdervelde, D.; Verbeelen, D.; Vanhaelen-Fastre, B.; et al. Rapidly progressive interstitial renal fibrosis in young women: Association with slimming regimen including Chinese herbs. Lancet 1993, 341, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, V.M.; Stiborova, M.; Schmeiser, H.H. Aristolochic acid as a probable human cancer hazard in herbal remedies: A review. Mutagenesis 2002, 17, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debelle, F.D.; Vanherweghem, J.L; Nortier, J.L. Aristolochic acid nephropathy: A worldwide problem. Kidney Int. 2008, 74, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeiser, H.H.; Stiborová, M.; Arlt, V.M. Chemical and molecular basis of the carcinogenicity of Aristolochia plants. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Dev. 2009, 12, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Gökmen, M.R.; Cosyns, J.P.; Arlt, V.M.; Stiborová, M.; Phillips, D.H.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Simmonds, M.S.J.; Look, H.T.; Vanherweghem, J.L.; Nortier, J.L.; et al. The epidemiology, diagnosis and management of Aristolochic Acid Nephropathy: A narrative review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nortier, J.L.; Martinez, M.C.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Arlt, V.M.; Bieler, C.A.; Petein, M.; Depierreux, M.F.; de Pauw, L.; Abramowicz, D.; Vereerstraeten, P.; et al. Urothelial carcinoma associated with the use of a Chinese herb (Aristolochia fangchi). N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 1686–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, V.M.; Ferluga, D.; Stiborova, M.; Pfohl-Leszkowicz, A.; Vukelic, M.; Ceovic, S.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Cosyns, J.P. Is aristolochic acid a risk factor for Balkan endemic nephropathy-associated urothelial cancer? Int. J. Cancer 2002, 101, 500–502. [Google Scholar]

- Arlt, V.M.; Stiborova, M.; vom Brocke, J.; Simoes, M.L.; Lord, G.M.; Nortier, J.L.; Hollstein, M.; Phillips, D.H.; Schmeiser, H.H. Aristolochic acid mutagenesis: Molecular clues to the aetiology of Balkan endemic nephropathy-associated urothelial cancer. Carcinogenesis 2007, 28, 2253–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grollman, A.P.; Shibutani, S.; Moriya, M.; Miller, F.; Wu, L.; Moll, U.; Suzuki, N.; Fernandes, A.; Rosenquist, T.; Medverec, Z.; et al. Aristolochic acid and the etiology of endemic (Balkan) nephropathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 12129–12134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moriya, M.; Slade, N.; Brdar, B.; Medverec, Z.; Tomic, K.; Jelakovic, B.; Wu, L.; Truong, S.; Fernandes, A.; Grollman, A.P. TP53 Mutational signature for aristolochic acid: an environmental carcinogen. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 129, 1532–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelakovic, B.; Nikolic, J.; Radovanovic, Z.; Nortier, J.; Cosyns, J.P.; Grollman, A.P.; Basic-Jukic, N.; Belicza, M.; Bukvic, D.; Cavaljuga, S.; et al. Consensus statement on screening, diagnosis, classification and treatment of endemic (Balkan) nephropathy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmeiser, H.H.; Bieler, C.A.; Wiessler, M.; van Ypersele de Strihou, C.; Cosyns, J.P. Detection of DNA adducts formed by aristolochic acid in renal tissue from patients with Chinese herbs nephropathy. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 2025–2028. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, B.H.; Rosenquist, T.A.; Sidorenko, V.; Iden, C.R.; Chen, C.H.; Pu, Y.S.; Bonala, R.; Johnson, F.; Dickman, K.G.; Grollman, A.P.; et al. Biomonitoring of aristolactam-DNA adducts in human tissues using ultra-performance liquid chromatography/ion-trap mass spectrometry. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012, 25, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Jelaković, B.; Karanović, S.; Vuković-Lela, I.; Miller, F.; Edwards, K.L.; Nikolić, J.; Tomić, K.; Slade, N.; Brdar, B.; Turesky, R.J.; et al. Aristolactam-DNA adducts are a biomarker of environmental exposure to aristolochic acid. Kidney Int. 2012, 81, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeiser, H.H.; Nortier, J.,L.; Singh, R.; Gamboa da Costa, G.; Sennesael, J.; Cassuto-Viguier, E.; Ambrosetti, D.; Rorive, S.; Pozdzik, A.; Phillips, D.H.; et al. Exceptionally long-term persistence of DNA adducts formed by carcinogenic aristolochic acid I in renal tissue from patients with aristolochic acid nephropathy. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 135, 502–507. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, G.M.; Hollstein, M.; Arlt, V.M.; Roufosse, C.; Pusey, C.D.; Cook, T.; Schmeiser, H.H. DNA adducts and p53 mutations in a patient with aristolochic acid-associated nephropathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2004, 43, e11–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Dickman, K.G.; Moriya, M.; Zavadil, J.; Sidorenko, V.S.; Edwards, K.L.; Gnatenko, D.V.; Wu, L.; Turesky, R.J.; Wu, X.R.; et al. Aristolochic acid-associated urothelial cancer in Taiwan. Proc.Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8241–8246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, M.L.; Chen, C.H.; Sidorenko, V.S.; He, J.; Dickman, K.G.; Yun, B.H.; Moriya, M.; Niknafs, N.; Douville, C.; Karchin, R.; et al. Mutational signature of aristolochic acid exposure as revealed by whole-exome sequencing. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, S.L.; Pang, S.T.; McPherson, J.R.; Yu, W.; Huang, K.K.; Guan, P.; Weng, W.H.; Siew, E.Y.; Liu, Y.; Heng, H.L. Genome-wide mutational signatures of aristolochic acid and its application as a screening tool. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 197ra101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, M.; Hollstein, M.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Straif, K.; Wild, C.P. Upper urinary tract urothelial cancer: Where it is A:T. Nat. Rev. 2012, 12, 503–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiborová, M.; Frei, E.; Arlt, V.M.; Schmeiser, H.H. Metabolic activation of carcinogenic aristolochic acid, a risk factor for Balkan endemic nephropathy. Mutat. Res. 2008, 658, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Stiborová, M.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H. Biotransformation enzymes in development of renal injury and urothelial cancer caused by aristolochic acid. Kidney Int. 2008, 73, 1209–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiborová, M.; Martínek, V.; Frei, E.; Arlt, V.M.; Schmeiser, H.H. Enzymes metabolizing aristolochic acid and their contribution to the development of Aristolochic acid nephropathy and urothelial cancer. Curr. Drug Metab. 2013, 14, 695–705. [Google Scholar]

- Stiborová, M.; Frei, E.; Arlt, V.M.; Schmeiser, H.H. Knock-out and humanized mice as suitable tools to identify enzymes metabolizing the human carcinogen aristolochic acid. Xenobiotica 2014, 44, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, V.M.; Stiborová, M.; Henderson, C.J.; Osborne, M.R.; Bieler, C.A.; Frei, E.; Martínek, V.; Sopko, B.; Wolf, C.R.; Schmeiser, H.H.; et al. The environmental pollutant and potent mutagen 3-nitrobenzanthrone forms DNA adducts after reduction by NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase and conjugation by acetyltransferases and sulfotransferases in human hepatic cytosols. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 2644–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiborová, M.; Dračínská, H.; Hájková, J.; Kadeřábková, P.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Souček, P.; Phillips, D.H.; Arlt, V.M. The environmental pollutant and carcinogen 3-nitrobenzanthrone and its human metabolite 3-aminobenzanthrone are potent inducers of rat hepatic cytochromes P450 1A1 and -1A2 and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006, 34, 1398–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiborová, M.; Dracínská, H.; Mizerovská, J.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Hudecek, J.; Hodek, P.; Phillips, D.H.; Arlt., V.M. The environmental pollutant and carcinogen 3-nitrobenzanthrone induces cytochrome P450 1A1 and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase in rat lung and kidney, thereby enhancing its own genotoxicity. Toxicology 2008, 247, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiborová, M.; Dracínská, H.; Martínková, M.; Mizerovská, J.; Hudecek, J.; Hodek, P.; Liberda, J.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Phillips, D.H.; et al. 3-aminobenzanthrone, a human metabolite of the carcinogenic environmental pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone, induces biotransformation enzymes in rat kidney and lung. Mutat. Res. 2009, 676, 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Stiborová, M.; Martínek, V.; Svobodová, M.; Sístková, J.; Dvorák, Z.; Ulrichová, J.; Simánek, V.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Phillips, D.H.; et al. Mechanisms of the different DNA adduct forming potentials of the urban air pollutants 2-nitrobenzanthrone and carcinogenic 3-nitrobenzanthrone. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2010, 23, 1192–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizerovská, J.; Dračínská, H.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Arlt, V.M.; Stiborová, M. Induction of biotransformation enzymes by the carcinogenic air-pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone in liver, kidney and lung, after intra-tracheal instillation in rats. Mutat. Res. 2011, 720, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Borlak, J.; Hansen, T.; Yuan, Z.X.; Sikka, H.C.; Kumar, S.; Schmidbauer, S.; Frank, H.; Jacob, J.; Seidel, A. Metabolism and DNA-binding of 3-nitrobenzanthrone in primary rat alveolar type II cells, in human fetal bronchial, rat epithelial and mesenchymal cell line. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2000, 21, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, V.M.; Phillips, D.H.; Reynisson, J. Theoretical investigations on the formation of nitrobenzanthrone-DNA adducts. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 6100–6110. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, M.R.; Arlt, V.M.; Kliem, C.; Hull, W.E.; Mirza, A.; Bieler, C.A.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Phillips, D.H. Synthesis, characterization, and 32P-postlabeling analysis of DNA adducts derived from the environmental contaminant 3-nitrobenzanthrone. Chem. Res.Toxicol. 2005, 18, 1056–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamura-Enya, T.; Kawanishi, M.; Yagi, T.; Hisamatsu, Y. Structural identification of DNA adducts derived from 3-nitrobenzanthrone, a potent carcinogen present in the atmosphere. Chem. Asian J. 2007, 2, 1174–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa da Costa, G.; Singh, R.; Arlt, V.M.; Mirza, A.; Richards, M.; Takamura-Enya, T.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Farmer, P.B.; Phillips, D.H. Quantification of 3-nitrobenzanthrone-DNA adducts using online column-switching HPLC-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009, 22, 1860–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfau, W.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Wiessler, M. 32P-postlabelling analysis of the DNA adducts formed by aristolochic acid I and II. Carcinogenesis 1990, 11, 1627–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.; Luo, H.B.; Zheng, Y.; Cheng, Y.K.; Cai, Z. Investigation of the metabolism and reductive activation of carcinogenic aristolochic acids in rats. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2007, 35, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiborova, M.; Hajek, M.; Vosmikova, H.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H. Isolation of DT-diaphorase [NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (quinone)] from rat liver cytosol: Identification of new enzyme substrates, carcinogenic aristolochic acids. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 2001, 66, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiborová, M.; Levová, K.; Bárta, F.; Šulc, M.; Frei, E.; Arlt, V.M.; Schmeiser, H.H. The influence of dicoumarol on the bioactivation of the carcinogen aristolochic acid I in rats. Mutagenesis 2014, 29, 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Arlt, V.M.; Zuo, J.; Trenz, K.; Roufosse, C.A.; Lord, G.M.; Nortier, J.L.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Hollstein, M.; Phillips, D.H. Gene expression changes induced by the human carcinogen aristolochic acid I in renal and hepatic tissue of mice. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 128, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levova, K.; Moserova, M.; Nebert, D.W.; Phillips, D.H.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Arlt, V.M.; Stiborova, M. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase expression in Cyp1a-knockout and CYP1A-humanized mouse lines and its effect on bioactivation of the carcinogen aristolochic acid I. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012, 265, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, F.; Levova, K.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Arlt, V.M.; Stiborova, M. The effect of aristolochic acid I on NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase expression in mice and rats—A comparative study. Mutat. Res. 2014, 768, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda, S.; Nakamura, W.; Hayashi, K. Properties and reaction mechanism of DT diaphorase from rat liver. J. Biol. Chem. 1974, 249, 6416–6423. [Google Scholar]

- Asher, G.; Dym, O.; Tsvetkov, P.; Adler, J.; Shaul, Y. The crystal structure of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 in complex with its potent inhibitor dicoumarol. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 6372–6378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiborová, M.; Frei, E.; Sopko, B.; Sopková, K.; Marková, V.; Laňková, M.; Kumstýřová, T.; Wiessler, M.; Schmeiser, H.H. Human cytosolic enzymes involved in the metabolic activation of carcinogenic aristolochic acid: Evidence for reductive activation by human NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase. Carcinogenesis 2003, 24, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiborová, M.; Mareš, J.; Frei, E.; Arlt, V.M.; Martínek, V.; Schmeiser, H.H. The human carcinogen aristolochic acid I is activated to form DNA adducts by human NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase without the contribution of acetyltransferases or sulfotransferases. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2011, 52, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Gong, L.; Qi, X.; Xing, G.; Luan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Yao, J.; Li, Y.; Xue, X.; et al. Inhibition of renal NQO1 activity by dicoumarol suppresses nitroreduction of aristolochic acid I and attenuates its nephrotoxicity. Toxicol. Sci. 2011, 122, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, V.M.; Glatt, H.; Muckel, E.; Pabel, U.; Sorg, B.L.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Phillips, D.H. Metabolic activation of the environmental contaminant 3-nitrobenzanthrone by human acetyltransferases and sulfotransferase. Carcinogenesis 2002, 1937–1945. [Google Scholar]

- Arlt, V.M.; Glatt, H.; Muckel, E.; Pabel, U.; Sorg, B.L.; Seidel, A.; Frank, H.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Phillips, D.H. Activation of 3-nitrobenzanthrone and its metabolites by human acetyltransferases, sulfotransferases and cytochrome P450 expressed in Chinese hamster V79 cells. Int. J. Cancer 2003, 105, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinek., V.; Kubickova, B.; Arlt, V.M.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Hudecek, J.; Stiborova, M. omparison of activation of aristolochic acid I and II with NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase, sulphotransferases and N-acetyltranferases. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2011, 32, S57–S70. [Google Scholar]

- Meinl, W.; Pabel, U.; Osterloh-Quiroz, M.; Hengstler, J.G.; Glatt, H. Human sulphotransferases are involved in the activation of aristolochic acids and are expressed in renal target tissue. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 118, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiborová, M.; Frei, E.; Wiessler, M.; Schmeiser, H.H. Human enzymes involved in the metabolic activation of carcinogenic aristolochic acids: Evidence for reductive activation by cytochromes P450 1A1 and 1A2. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001, 14, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiborová, M.; Hájek, M.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H. Carcinogenic and nephrotoxic alkaloids aristolochic acids upon activation by NADPH:cytochrome P450 reductase form adducts found in DNA of patients with Chinese herbs nephropathy. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2001, 20, 375–392. [Google Scholar]

- Stiborová, M.; Frei, E.; Hodek, P.; Wiessler, M.; Schmeiser, H.H. Human hepatic and renal microsomes, cytochromes P450 1A1/2, NADPH:cytochrome P450 reductase and prostaglandin H synthase mediate the formation of aristolochic acid-DNA adducts found in patients with urothelial cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 113, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiborová, M.; Sopko, B.; Hodek, P.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Hudecek, J. The binding of aristolochic acid I to the active site of human cytochromes P450 1A1 and 1A2 explains their potential to reductively activate this human carcinogen. Cancer Lett. 2005, 229, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, V.M.; Stiborová, M.; Hewer, A.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Phillips, D.H. Human enzymes involved in the metabolic activation of the environmental contaminant 3-nitrobenzanthrone: Evidence for reductive activation by human NADPH:cytochrome P450 reductase. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 2752–2761. [Google Scholar]

- Arlt, V.M.; Hewer, A.; Sorg, B.L.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Phillips, D.H.; Stiborova, M. 3-aminobenzanthrone, a human metabolite of the environmental pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone, forms DNA adducts after metabolic activation by human and rat liver microsomes: Evidence for activation by cytochrome P450 1A1 and P450 1A2. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2004, 17, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slepneva, I.A.; Sergeeva, S.V.; Khramtsov, V.V. Reversible inhibition of NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase by α-lipoic acid. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 214, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drahushuk, A.T.; McGarrigle, B.P.; Larsen, K.E.; Stegeman, J.J.; Olson, J.R. Detection of CYP1A1 protein in human liver and induction by TCDD in precision-cut liver slices incubated in dynamic organ culture. Carcinogenesis 1998, 19, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiborová, M.; Martínek, V.; Rýdlová, H.; Hodek, P.; Frei, E. Sudan I is a potential carcinogen for humans: Evidence for its metabolic activation and detoxication by human recombinant cytochrome P450 1A1 and liver microsomes. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 5678–5684. [Google Scholar]

- Dragin, N.; Uno, S.; Wang, B.; Dalton, T.P.; Nebert, D.W. Generation of “humanized” hCYP1A1_1A2_Cyp1a1/1a2−/− mouse line. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 359, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Chen, Y.; Dong, H.; Amos-Kroohs, R.M.; Nebert, D.W. Generation of a “humanized” hCYP1A1_1A2_Cyp1a1/1a2−/−_Ahrd mouse line harboring the poor-affinity aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 376, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiborová, M.; Levová, K.; Bárta, F.; Shi, Z.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Nebert, D.W.; Phillips, D.H.; Arlt, V.M. Bioactivation versus detoxication of the urothelial carcinogen aristolochic acid I by human cytochrome P450 1A1 and 1A2. Toxicol. Sci. 2012, 125, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, V.M.; Levová, K.; Bárta, F.; Shi, Z.; Evans, J.D.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Nebert, D.W.; Phillips, D.H.; Stiborová, M. Role of P450 1A1 and P450 1A2 in bioactivation versus detoxication of the renal carcinogen aristolochic acid I: studies in Cyp1a1−/−, Cyp1a2−/−, and Cyp1a1/1a2−/− mice. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011, 24, 1710–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendic, S.; DiCarlo, F.J. Human cytochrome P450 enzymes: A status report summarizing their reactions, substrates, inducers, and inhibitors. Drug Metab. Rev. 1997, 29, 413–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levová, K.; Moserová, M.; Kotrbová, V.; Šulc, M.; Henderson, C.J.; Wolf, C.R.; Phillips, D.H.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Mareš, J.; et al. Role of cytochromes P450 1A1/2 in detoxication and activation of carcinogenic aristolochic acid I: Studies with the hepatic NADPH:cytochrome P450 reductase null (HRN) mouse model. Toxicol. Sci 2011, 121, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerabek, P.; Martinek, V.; Stiborova, M. Theoretical investigation of differences in nitroreduction of aristolochic acid I by cytochromes P450 1A1, 1A2 and 1B1. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2012, 33, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sistkova, J.; Hudecek, J.; Hodek, P.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Stiborova, M. Human cytochromes P450 1A1 and 1A2 participate in detoxication of carcinogenic aristolochic acid. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2008, 29, 733–737. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Ge, M.; Xue, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Wu, X.; Li, L.; Liu, L.; Qi, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Hepatic cytochrome P450s metabolize aristolochic acid and reduce its kidney toxicity. Kidney Int. 2008, 73, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenquist, T.A.; Einolf, H.J.; Dickman, K.G.; Wang, L.; Smith, A.; Grollman, A.P. Cytochrome P450 1A2 detoxicates aristolochic acid in the mouse. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2010, 38, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W; Schlegel, H.B; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Montgomery, J.A., Jr.; Vreven, T.; Kudin, K.N.; Burant, J.C.; et al. Gaussian 03®; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cossi, M.; Rega, N.; Scalmani, G. Energies, structures, and electronic properties of molecules in solution with the C-PCM solvation model. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 669–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, J.; Warshel, A. Langevin dipoles model for ab initio calculations of chemical processes in solution: Parametrization and application to hydration free energies of neutral and ionic solutes and conformational analysis in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 5583–5595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, V.M.; Wiessler, M.; Schmeiser, H.H. Using polymerase arrest to detect DNA binding specificity of aristolochic acid in the mouse H-ras gene. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, V.M.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Pfeifer, G.P. Sequence-specific detection of aristolochic acid-DNA adducts in the human p53 gene by terminal transferase-dependent PCR. Carcinogenesis 2001, 22, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Priestap, H.A.; de los Santos, C.; Quirke, J.M. Identification of a reduction product of aristolochic acid: Implications for the metabolic activation of carcinogenic aristolochic acid. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 1979–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, J.; Warshel, A. Calculations of hydration entropies of hydrophobic, polar, and ionic solutes in the framework of the Langevin dipoles solvation model. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 10282–10288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faig, M.; Bianchet, M.A.; Talalay, P.; Chen, S.; Winski, S.; Ross, D.; Amzel, L.M. Structures of recombinant human and mouse NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductases: species comparison and structural changes with substrate binding and release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 3177–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Fisher, D.; Spidel, J.; Greenfield, J.; Patson, B.; Fazal, A.; Wigal, C.; Moe, O.A.; Madura, J.D. Kinetic and docking studies of the interaction of quinones with the quinone reductase active site. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 1985–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Stiborová, M.; Frei, E.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Arlt, V.M.; Martínek, V. Mechanisms of Enzyme-Catalyzed Reduction of Two Carcinogenic Nitro-Aromatics, 3-Nitrobenzanthrone and Aristolochic Acid I: Experimental and Theoretical Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 10271-10295. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms150610271

Stiborová M, Frei E, Schmeiser HH, Arlt VM, Martínek V. Mechanisms of Enzyme-Catalyzed Reduction of Two Carcinogenic Nitro-Aromatics, 3-Nitrobenzanthrone and Aristolochic Acid I: Experimental and Theoretical Approaches. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2014; 15(6):10271-10295. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms150610271

Chicago/Turabian StyleStiborová, Marie, Eva Frei, Heinz H. Schmeiser, Volker M. Arlt, and Václav Martínek. 2014. "Mechanisms of Enzyme-Catalyzed Reduction of Two Carcinogenic Nitro-Aromatics, 3-Nitrobenzanthrone and Aristolochic Acid I: Experimental and Theoretical Approaches" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 15, no. 6: 10271-10295. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms150610271