On the Influence of Crosslinker on Template Complexation in Molecularly Imprinted Polymers: A Computational Study of Prepolymerization Mixture Events with Correlations to Template-Polymer Recognition Behavior and NMR Spectroscopic Studies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

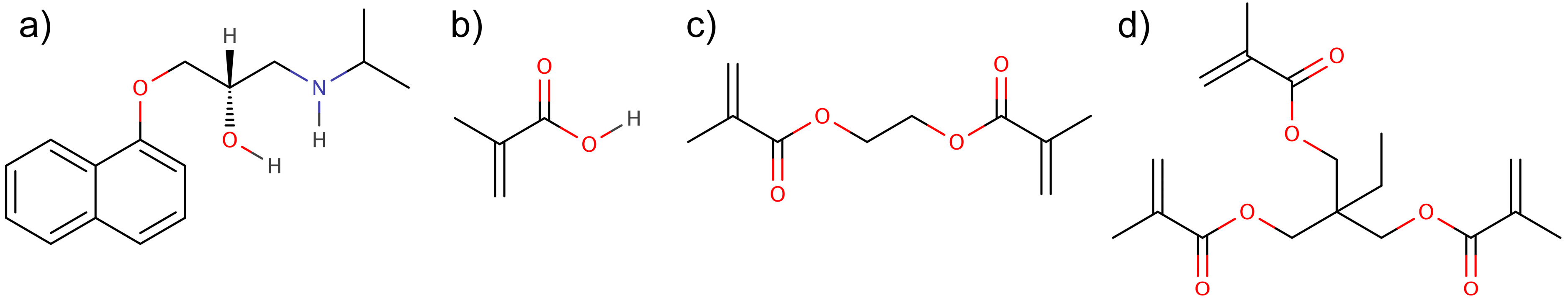

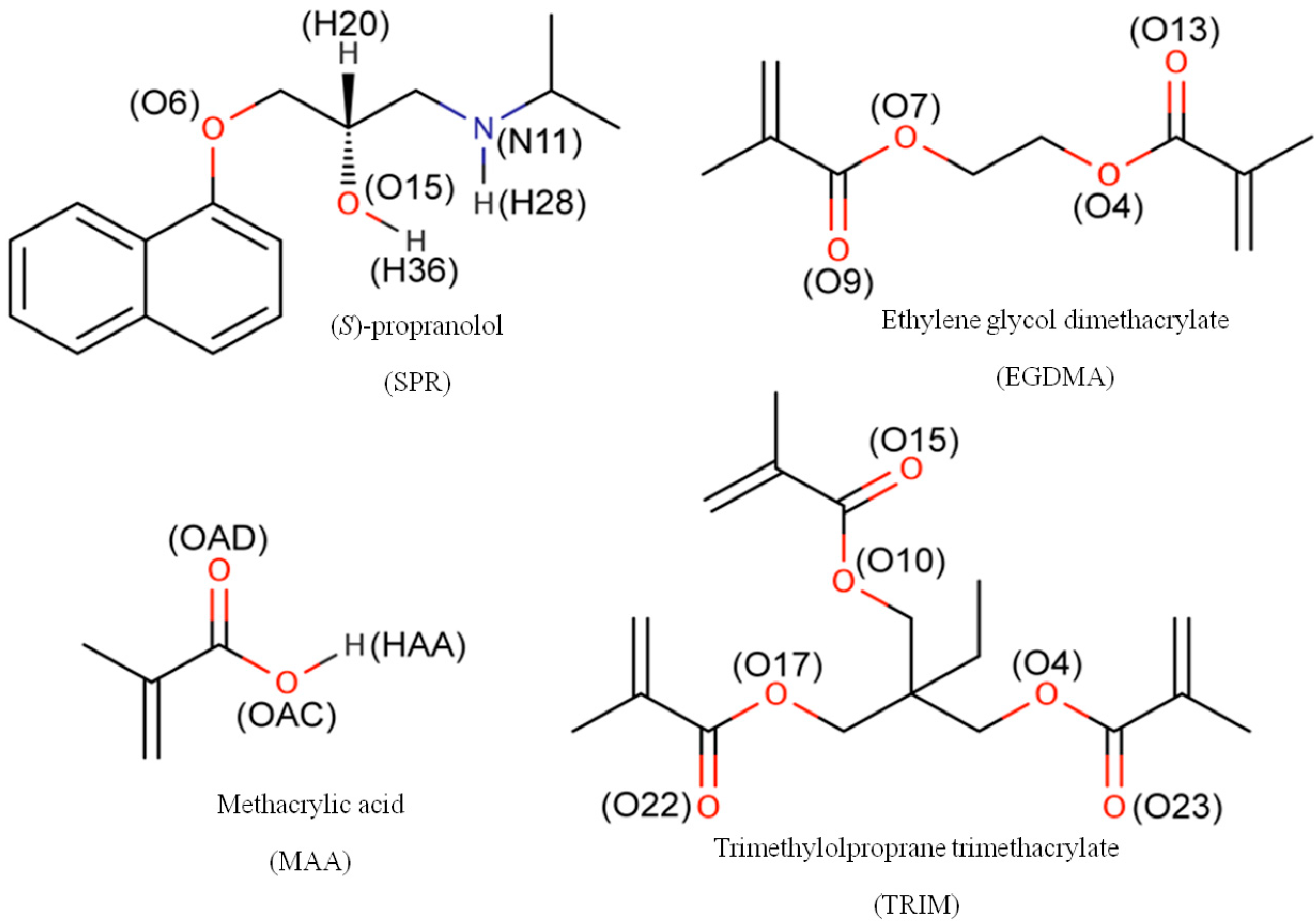

| Component | System A | System B |

|---|---|---|

| (S)-propranolol (SPR) | 10 | 10 |

| Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA) | 398 | - |

| Trimethylolproprane trimethacrylate (TRIM) | - | 80 |

| Methacrylic acid (MAA) | 80 | 80 |

| Toluene | 1012 | 393 |

| Azobisisobutyronitrile | 6 | 2 |

| Component | System A | System B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGDMA | MAA | TRIM | MAA | |

| SPR | 55.5 | 8.5 | 35.8 | 30.8 |

| MAA | 61.9 | n.a. | 38.6 | n.a. |

| Component | Atom | System A | System B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAA | SPR | MAA | SPR | |||||

| HAA | H28 | H36 | HAA | H28 | H36 | |||

| SPR | N11 | 2.8 (2.23) b | n.a. | n.a. | 12.2 (2.20) | n.a. | n.a. | |

| O6 | 0.1 (0.09) | n.a. | n.a. | 0.2 (0.14) | n.a. | n.a. | ||

| O15 | 2.8 (1.63) | n.a. | n.a. | 6.2 (1.74) | n.a. | n.a. | ||

| MAA | OAC | n.a.c | 0.1 (0.03) | 0.2 (0.14) | n.a. | 0.2 (0.11) | 0.7 (0.31) | |

| OAD | n.a. | 1.0 (0.78) | 1.6 (0.96) | n.a. | 4.4 (1.20) | 7.0 (0.85) | ||

| EGDMA | O4 | 0.1 (0.02) | 0.1 (0.07) | 0.1 (0.05) | - | - | - | |

| O7 | 0.1 (0.02) | 0.1 (0.06) | 0.0 (0.02) | - | - | - | ||

| O9 | 29.9 (2.67) | 11.5 (1.65) | 16.4 (4.11) | - | - | - | ||

| O13 | 31.8 (2.02) | 10.3 (2.05) | 17.0 (3.20) | - | - | - | ||

| TRIM | O15 | - | - | - | 13.5 (1.15) | 3.8 (1.40) | 8.2 (3.39) | |

| O22 | - | - | - | 12.3 (1.68) | 3.8 (2.10) | 8.1 (5.77) | ||

| O23 | - | - | - | 12.7 (1.82) | 3.6 (1.38) | 8.4 (3.41) | ||

| O4 | - | - | - | 0.0 (0.00) | 0.0 (0.00) | 0.0 (0.00) | ||

| O10 | - | - | - | 0.0 (0.00) | 0.0 (0.00) | 0.0 (0.00) | ||

| O17 | - | - | - | 0.0 (0.00) | 0.0 (0.00) | 0.0 (0.00) | ||

| Component | Atom | System A | System C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAA | SPR | MAA | SPR | ||||

| HAA | H28 | H36 | HAA | H28 | H36 | ||

| SPR | N11 | 1.7 (0.30) b | n.a. | n.a. | 1.9 (0.04) | n.a. | n.a. |

| O6 | 0.8 (0.13) | n.a. | n.a. | 0.7 (0.03) | n.a. | n.a. | |

| O15 | 1.7 (0.13) | n.a. | n.a. | 1.7 (0.14) | n.a. | n.a. | |

| MAA | OAC | n.a. c | 0.6 (0.03) | 0.7 (0.10) | n.a. | 0.6 (0.02) | 0.8 (0.06) |

| OAD | n.a. | 0.8 (0.05) | 1.4 (0.47) | n.a. | 0.8 (0.03) | 1.6 (0.11) | |

| EGDMA | O4 | 0.7 (0.03) | 0.6 (0.06) | 0.6 (0.03) | - | - | - |

| O7 | 0.7 (0.03) | 0.6 (0.05) | 0.6 (0.05) | - | - | - | |

| O9 | 3.4 (0.09) | 0.8 (0.05) | 1.5 (0.15) | - | - | - | |

| O13 | 3.3 (0.13) | 0.8 (0.04) | 1.7 (0.10) | - | - | - | |

| TRIM | O15 | - | - | - | 3.3 (0.06) | 0.9 (0.06) | 1.7 (0.26) |

| O22 | - | - | - | 3.1 (0.20) | 0.8 (0.03) | 1.6 (0.26) | |

| O23 | - | - | - | 3.1 (0.15) | 0.8 (0.04) | 1.7 (0.26) | |

| O4 | - | - | - | 0.6 (0.03) | 0.0 (0.00) | 0.0 (0.00) | |

| O10 | - | - | - | 0.6 (0.03) | 0.0 (0.00) | 0.0 (0.00) | |

| O17 | - | - | - | 0.5 (0.03) | 0.0 (0.00) | 0.0 (0.00) | |

2.2. Correlations with Polymer-Template Binding and NMR Studies

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

3.3. 1H-NMR Studies

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, S.G. Fabrication of novel biomaterials through molecular self-assembly. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Sellergren, B. Molecularly Imprinted Polymers: Man-Made Mimics of Antibodies and Their Applications in Analytical Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C.; Andersson, H.S.; Andersson, L.I.; Ansell, R.J.; Kirsch, N.; Nicholls, I.A.; O’Mahony, J.; Whitcombe, M.J. Molecular imprinting science and technology: A survey of the literature for the years up to and including 2003. J. Mol. Recognit. 2006, 19, 106–180. [Google Scholar]

- Whitcombe, M.J.; Kirsch, N.; Nicholls, I.A. Molecular imprinting science and technology: A survey of the literature for the years 2004–2011. J. Mol. Recognit. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulff, G. Molecular imprinting in cross-linked materials with the aid of molecular templates—A way towards artificial antibodies. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 1812–1832. [Google Scholar]

- Haupt, K.; Mosbach, K. Molecularly imprinted polymers and their use in biomimetic sensors. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 2495–2504. [Google Scholar]

- Whitcombe, M.J.; Chianella, I.; Larcombe, L.; Piletsky, S.A.; Noble, J.; Porter, R.; Horgan, A. The rational development of molecularly imprinted polymer-based sensors for protein detection. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1547–1571. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Komiyama, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Mukawa, T.; Asanuma, H. Molecular Imprinting; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vlatakis, G.; Andersson, L.I.; Müller, R.; Mosbach, K. Drug assay using antibody mimics made by molecular imprinting. Nature 1993, 361, 645–647. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, L.I.; Müller, R.; Vlatakis, G.; Mosbach, K. Mimics of the binding sites of opioid receptors obtained by molecular imprinting of enkephalin and morphine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995, 92, 4788–4792. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund, J.; Nicholls, I.A.; Lindbladh, C.; Mosbach, K. Recognition in molecularly imprinted polymer α2-adrenoreceptor mimics. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1996, 6, 2237–2242. [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger, E.; Möder, M.; Olsson, G.D.; Nicholls, I.A.; Sellergren, B. An artificial estrogen receptor through combinatorial imprinting. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 14773–14783. [Google Scholar]

- Sellergren, B.; Allender, C.J. Molecularly imprinted polymers: A bridge to advanced drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005, 57, 1733–1741. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino, Y.; Koide, H.; Urakami, T.; Kanazawa, H.; Kodama, T.; Oku, N.; Shea, K.J. Recognition, neutralization, and clearance of target peptides in the bloodstream of living mice by molecularly imprinted polymer nanoparticles: A plastic antibody. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6644–6645. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino, Y.; Koide, H.; Furuya, K.; Haberaecker, W.W.; Lee, S.-H.; Kodama, T.; Kanazawa, H.; Oku, N.; Shea, K.J. The rational design of a synthetic polymer nanoparticle that neutralizes a toxic peptide in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Piletska, E.V.; Stavroulakis, G.; Larcombe, L.D.; Whitcombe, M.J.; Sharma, A.; Primrose, S.; Robinson, G.K.; Piletsky, S.A. Passive control of quorum sensing: Prevention of pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation by imprinted polymers. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 1067–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Svenson, J.; Nicholls, I.A. On the thermal and chemical stability of molecularly imprinted polymers. Anal. Chim. Acta 2001, 435, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe, K.; Takeuchi, T.; Matsui, J.; Ikebukuro, K.; Yano, K.; Karube, I. Recognition of barbiturates in molecularly imprinted copolymers using multiple hydrogen-bonding. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1995, 1995, 2303–2304. [Google Scholar]

- Piletsky, S.A.; Andersson, H.S.; Nicholls, I.A. Combined hydrophobic and electrostatic interaction-based recognition in molecularly imprinted polymers. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 633–636. [Google Scholar]

- Wulff, G.; Schonfeld, R. Polymerizable amidines—Adhesion mediators and binding sites for molecular imprinting. Adv. Mater. 1998, 10, 957–959. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A.J.; Manesiotis, P.; Emgenbroich, M.; Quaglia, M.; de Lorenzi, E.; Sellergren, B. Urea host monomers for stoichiometric molecular imprinting of oxyanions. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 1732–1736. [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam, S.; Piletsky, S.A.; Piletska, E.V.; Chen, B.; Karim, K.; Turner, A.P. “Bite-and-Switch” approach using computationally designed molecularly imprinted polymers for sensing of creatinine. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2001, 16, 631–637. [Google Scholar]

- Chianella, I.; Lotierzo, M.; Piletsky, S.A.; Tothill, I.E.; Chen, B.; Karim, K.; Turner, A.P.F. Rational design of a polymer specific for microcystin-LR using a computational approach. Anal. Chem. 2002, 74, 1288–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Chianella, I.; Karim, K.; Piletska, E.V.; Preston, C.; Piletsky, S.A. Computational design and synthesis of molecularly imprinted polymers with high binding capacity for pharmaceutical applications-model case: Adsorbent for abacavir. Anal. Chim. Acta 2006, 559, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kempe, M. Antibody-mimicking polymers as chiral stationary phases in HPLC. Anal. Chem. 1996, 68, 1948–1953. [Google Scholar]

- Sibrian-Vazquez, M.; Spivak, D.A. Enhanced enantioselectivity of molecularly imprinted polymers formulated with novel cross-linking monomers. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 5105–5113. [Google Scholar]

- Sibrian-Vazquez, M.; Spivak, D.A. Molecular imprinting made easy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 7827–7833. [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, K.; Kuwahara, A.; Ohmori, K.; Takeuchi, T. Molecularly imprinted tunable binding sites based on conjugated prosthetic groups and ion-paired cofactors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 8833–8838. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmi, D.; Whitcombe, M.J.; Davis, F.; Chianella, I.; Piletska, E.V.; Guerreiro, A.; Subrahmanyam, S.; Brito, P.S.; Fowler, S.A.; Piletsky, S.A. Chimeric polymers formed from a monomer capable of free radical, oxidative and electrochemical polymerisation. Chem. Commun. 2009, 2009, 2759–2761. [Google Scholar]

- Golker, K.; Karlsson, B.C.G.; Olsson, G.D.; Rosengren, A.M.; Nicholls, I.A. Influence of composition and morphology on template recognition in molecularly imprinted polymers. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 1408–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch, N.; Hedin-Dahlstrom, J.; Henschel, H.; Whitcombe, M.J.; Wikman, S.; Nicholls, I.A. Molecularly imprinted polymer catalysis of a Diels-Alder reaction. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2009, 58, 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Henschel, H.; Kirsch, N.; Hedin-Dahlstrom, J.; Whitcombe, M.J.; Wikman, S.; Nicholls, I.A. Effect of the cross-linker on the general performance and temperature dependent behaviour of a molecularly imprinted polymer catalyst of a Diels-Alder reaction. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2011, 72, 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, L.I. Application of molecular imprinting to the development of aqueous buffer and organic solvent based radioligand binding assays for (S)-propranolol. Anal. Chem. 1996, 68, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, S.; Schweitz, L.; Petersson, M. Three approaches to enantiomer separation of β-adrenergic antagonists by capillary electrochromatography. Electrophoresis 1997, 18, 884–890. [Google Scholar]

- Haginaka, J.; Sakai, Y.; Narimatsu, S. Uniform-sized molecularly imprinted polymer material for propranolol recognition of propranolol and its metabolites. Anal. Sci. 1998, 14, 823–826. [Google Scholar]

- Mullett, W.M.; Martin, P.; Pawliszyn, J. In-tube molecularly imprinted polymer solid-phase microextraction for the selective determination of propranolol. Anal. Chem. 2001, 73, 2383–2389. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitz, L.; Andersson, L.I.; Nilsson, S. Rapid electrochromatographic enantiomer separations on short molecularly imprinted polymer monoliths. Anal. Chim. Acta 2001, 435, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Fireman-Shoresh, S.; Popov, I.; Avnir, D.; Marx, S. Enantioselective, chirally templated sol-gel thin films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 2650–2655. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R.H.; Haupt, K. Molecularly imprinted polymer films with binding properties enhanced by the reaction-induced phase separation of a sacrificial polymeric porogen. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R.H.; Belmont, A.S.; Haupt, K. Porogen formulations for obtaining molecularly imprinted polymers with optimized binding properties. Anal. Chim. Acta 2005, 542, 118–124. [Google Scholar]

- Castell, O.K.; Allender, C.J.; Barrow, D.A. Novel biphasic separations utilising highly selective molecularly imprinted polymers as biorecognition solvent extraction agents. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006, 22, 526–533. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Moral, N.; Mayes, A.G. Direct rapid synthesis of MIP beads in SPE cartridges. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006, 21, 1798–1803. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Yoshimatsu, K.; Kolodziej, D.; da Cruz Francisco, J.; Dey, E.S. Preparation of molecularly imprinted polymers in supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 102, 2863–2867. [Google Scholar]

- Reimhult, K.; Yoshimatsu, K.; Risveden, K.; Chen, S.; Ye, L.; Krozer, A. Characterization of QCM sensor surfaces coated with molecularly imprinted nanoparticles. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2008, 23, 1908–1914. [Google Scholar]

- Bompart, M.; Gheber, L.A.; de Wilde, Y.; Haupt, K. Direct detection of analyte binding to single molecularly imprinted polymer particles by confocal Raman spectroscopy. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 25, 568–571. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Y.; Philip, J.Y.N.; Schillen, K.; Liu, F.; Ye, L. Insight into molecular imprinting in precipitation polymerization systems using solution NMR and dynamic light scattering. J. Mol. Recognit. 2011, 24, 619–630. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Ye, L. Clickable molecularly imprinted nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 6096–6098. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, I.A.; Andersson, H.S.; Charlton, C.; Henschel, H.; Karlsson, B.C.G.; Karlsson, J.G.; O’Mahony, J.; Rosengren, A.M.; Rosengren, J.K.; Wikman, S. Theoretical and computational strategies for rational molecularly imprinted polymer design. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 25, 543–552. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, I.A.; Andersson, H.S.; Golker, K.; Henschel, H.; Karlsson, B.C.G.; Olsson, G.D.; Rosengren, A.M.; Shoravi, S.; Suriyanarayanan, S.; Wiklander, J.G.; et al. Rational design of biomimetic molecularly imprinted materials: Theoretical and computational strategies for guiding nanoscale structured polymer development. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 400, 1771–1786. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, I.A.; Karlsson, B.C.G.; Olsson, G.D.; Rosengren, A.M. Computational strategies for the design and study of molecularly imprinted materials. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 13900–13909. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, B.C.G.; O’Mahony, J.; Karlsson, J.G.; Bengtsson, H.; Eriksson, L.A.; Nicholls, I.A. Structure and dynamics of monomer-template complexation: An explanation for molecularly imprinted polymer recognition site heterogeneity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 13297–13304. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, G.D.; Karlsson, B.C.G.; Shoravi, S.; Wiklander, J.G.; Nicholls, I.A. Mechanisms underlying molecularly imprinted polymer molecular memory and the role of crosslinker: Resolving debate on the nature of template recognition in phenylalanine anilide imprinted polymers. J. Mol. Recognit. 2012, 25, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Atta, N.F.; Hamed, M.M.; Abdel-Mageed, A.M. Computational investigation and synthesis of a sol-gel imprinted material for sensing application of some biologically active molecules. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 667, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, B.C.G.; Rosengren, A.M.; Näslund, I.; Andersson, P.O.; Nicholls, I.A. Synthetic human serum albumin sudlow I binding site mimics. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 7932–7937. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, G.D.; Karlsson, B.C.G.; Schillinger, E.; Sellergren, B.; Nicholls, I.A. Theoretical studies of 17-β-estradiol-imprinted prepolymerization mixtures: Insights concerning the roles of cross-linking and functional monomers in template complexation and polymerization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 13965–13970. [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony, J.; Karlsson, B.C.G.; Mizaikoff, B.; Nicholls, I.A. Correlated theoretical, spectroscopic and X-ray crystallographic studies of a non-covalent molecularly imprinted polymerisation system. Analyst 2007, 132, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Case, D.A.; Cheatham, T.E.; Darden, T.; Gohlke, H.; Luo, R.; Merz, K.M.; Onufriev, A.; Simmerling, C.; Wang, B.; Woods, R.J. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1668–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Case, D.A.; Darden, T.A.; Cheatham, T.E.I.; Simmerling, C.L.; Wang, J.; Duke, R.E.; Luo, R.; Crowley, M.; Walker, R.C.; Zhang, W.; et al. Amber 10; University of California: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.; Wu, C.; Chowdhury, S.; Lee, M.C.; Xiong, G.; Zhang, W.; Yang, R.; Cieplak, P.; Luo, R.; Lee, T.; et al. A point-charge force field for molecular mechanics simulations of proteins based on condensed-phase quantum mechanical calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 1999–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wolf, R.M.; Caldwell, J.W.; Kollman, P.A.; Case, D.A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1157–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, J.M.; Martínez, L. Packing optimization for automated generation of complex system’s initial configurations for molecular dynamics and docking. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 819–825. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, L.; Andrade, R.; Birgin, E.G.; Martínez, J.M. PACKMOL: A package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2157–2164. [Google Scholar]

- Svenson, J.; Andersson, H.S.; Piletsky, S.A.; Nicholls, I.A. Spectroscopic studies of the molecular imprinting self-assembly process. J. Mol. Recognit. 1998, 11, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Shoravi, S.; Olsson, G.D.; Karlsson, B.C.G.; Nicholls, I.A. On the Influence of Crosslinker on Template Complexation in Molecularly Imprinted Polymers: A Computational Study of Prepolymerization Mixture Events with Correlations to Template-Polymer Recognition Behavior and NMR Spectroscopic Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 10622-10634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms150610622

Shoravi S, Olsson GD, Karlsson BCG, Nicholls IA. On the Influence of Crosslinker on Template Complexation in Molecularly Imprinted Polymers: A Computational Study of Prepolymerization Mixture Events with Correlations to Template-Polymer Recognition Behavior and NMR Spectroscopic Studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2014; 15(6):10622-10634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms150610622

Chicago/Turabian StyleShoravi, Siamak, Gustaf D. Olsson, Björn C. G. Karlsson, and Ian A. Nicholls. 2014. "On the Influence of Crosslinker on Template Complexation in Molecularly Imprinted Polymers: A Computational Study of Prepolymerization Mixture Events with Correlations to Template-Polymer Recognition Behavior and NMR Spectroscopic Studies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 15, no. 6: 10622-10634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms150610622