PAMAM Dendrimers Cross the Blood–Brain Barrier When Administered through the Carotid Artery in C57BL/6J Mice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

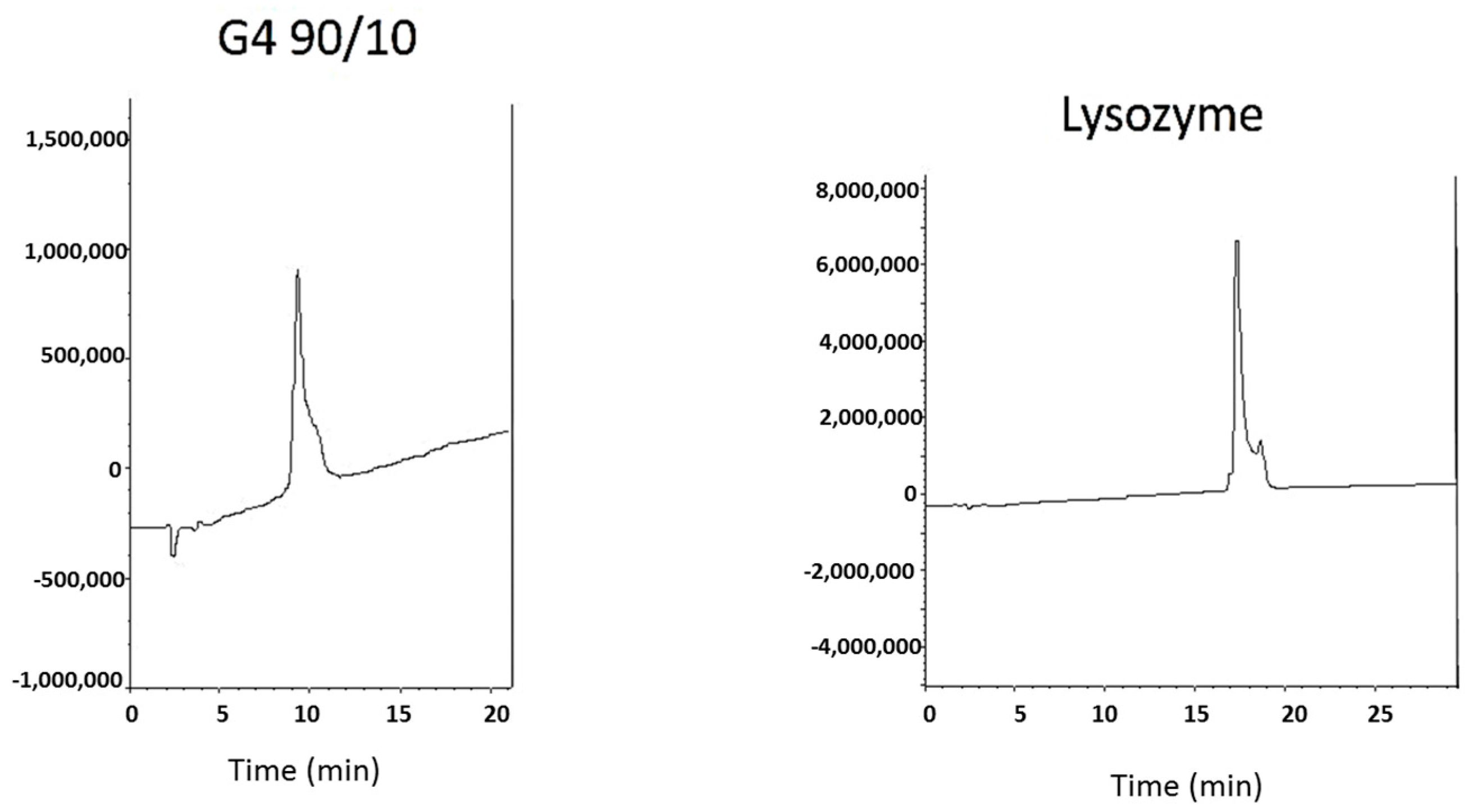

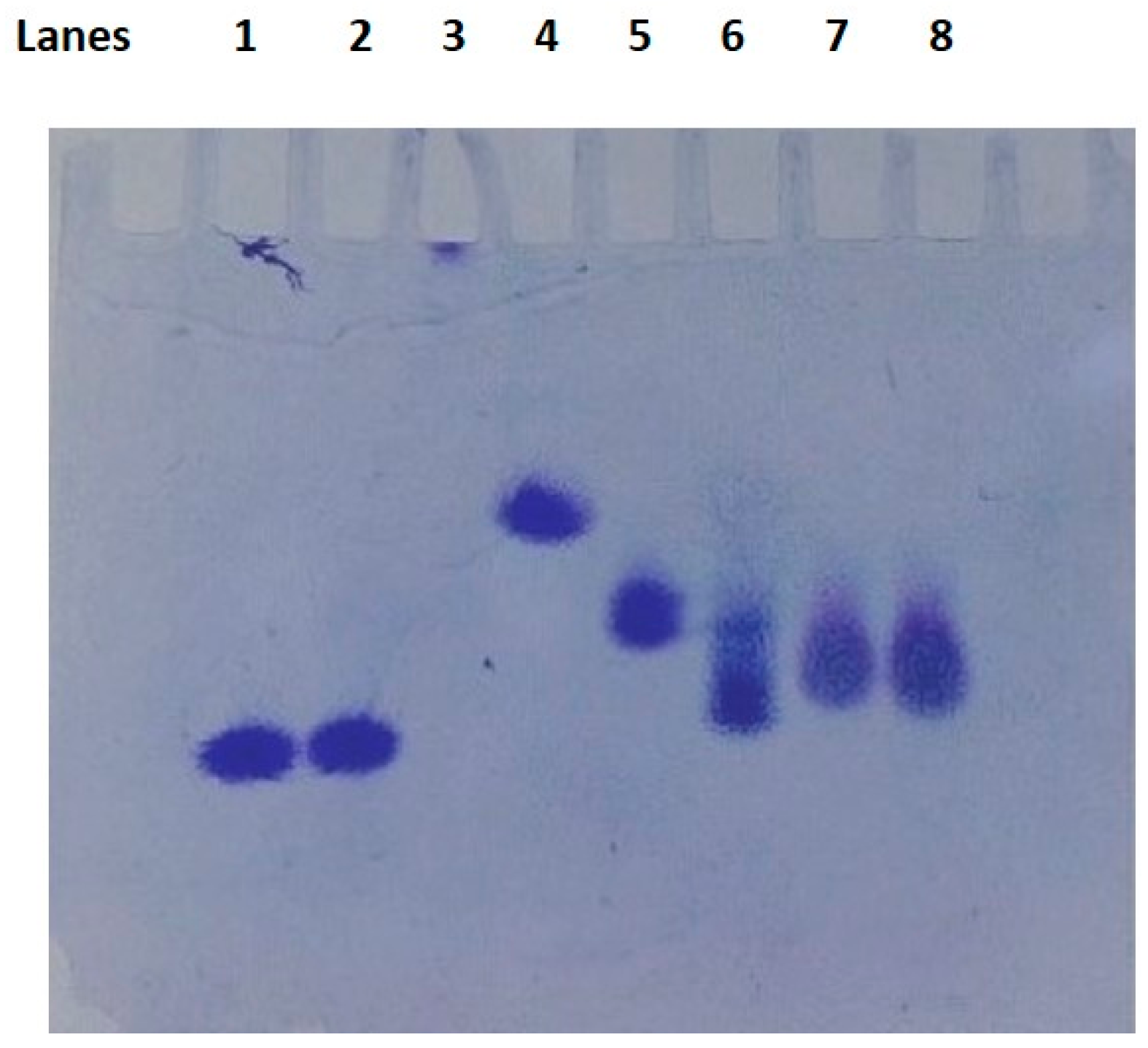

2.1. Dendrimer Characterization

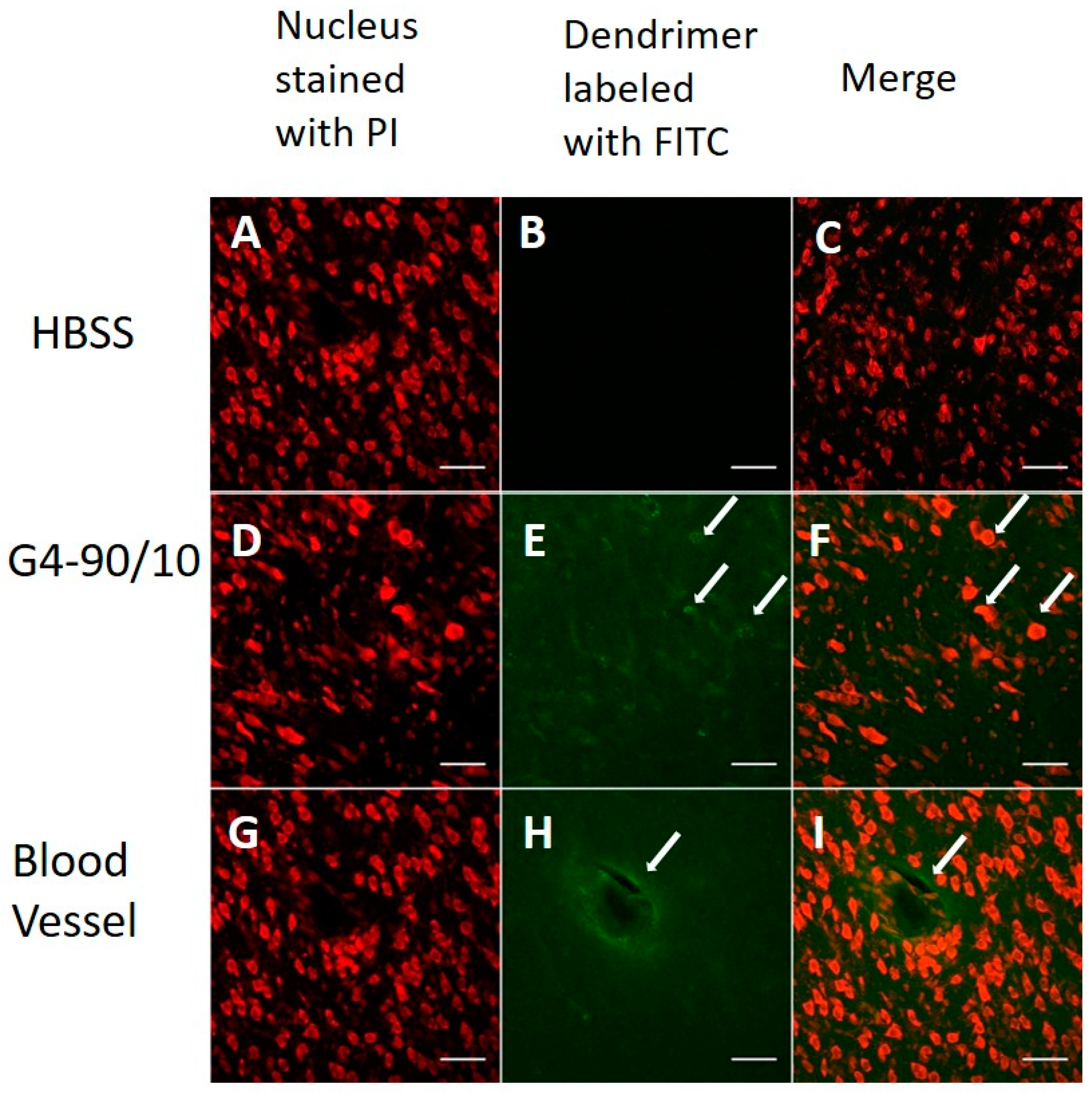

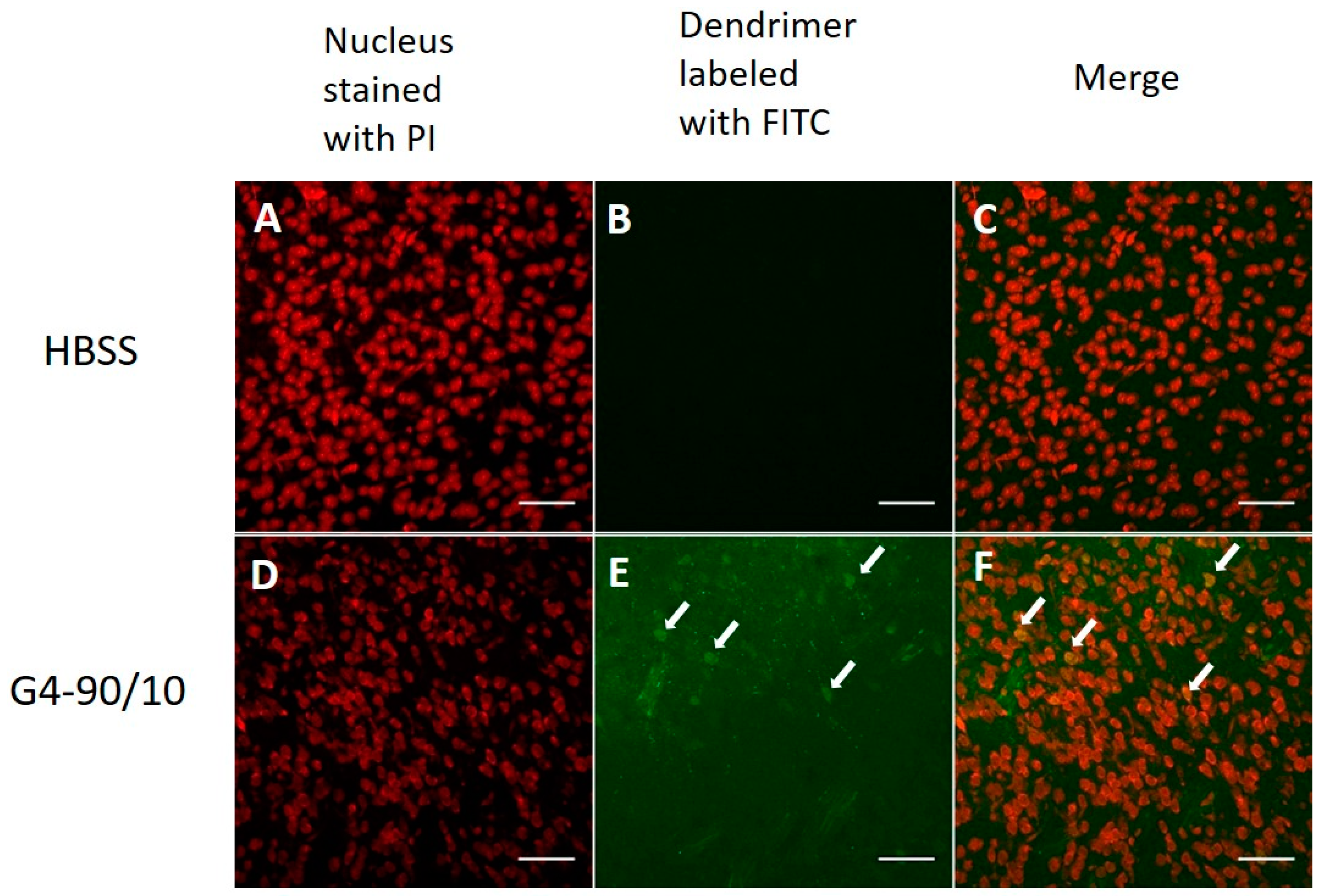

2.2. In Vitro Primary Cortical Culture Infection with Dendrimers

2.2.1. Cationic Dendrimers

2.2.2. Mixed Surface Dendrimers

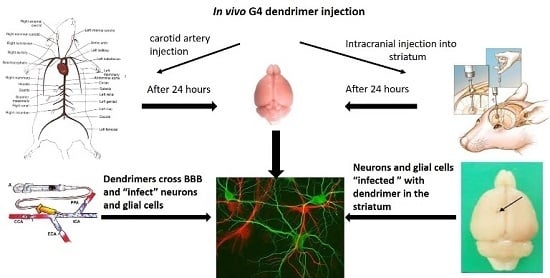

2.3. Localization of Dendrimers In Vivo

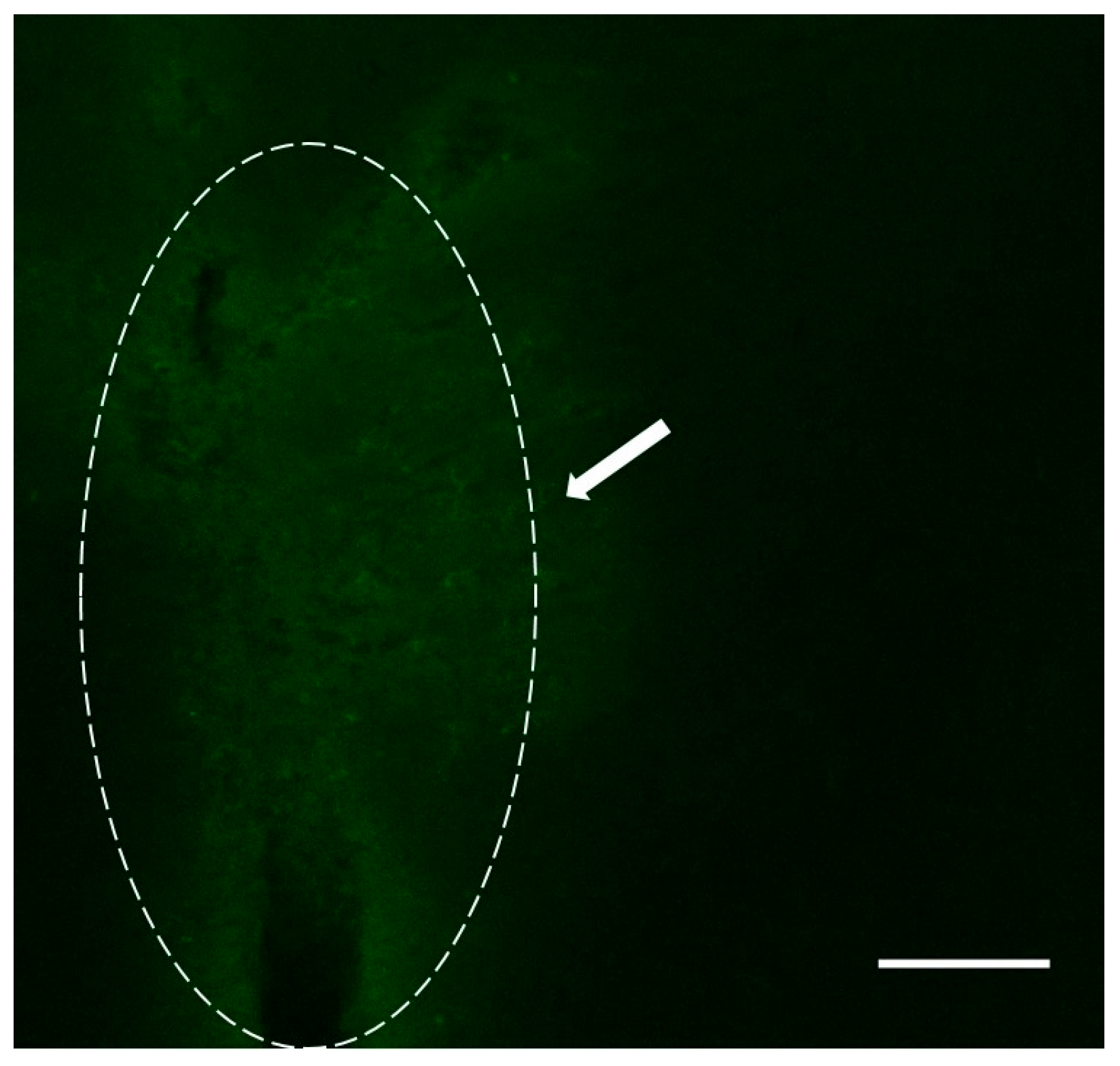

2.3.1. Carotid Injection of Dendrimers

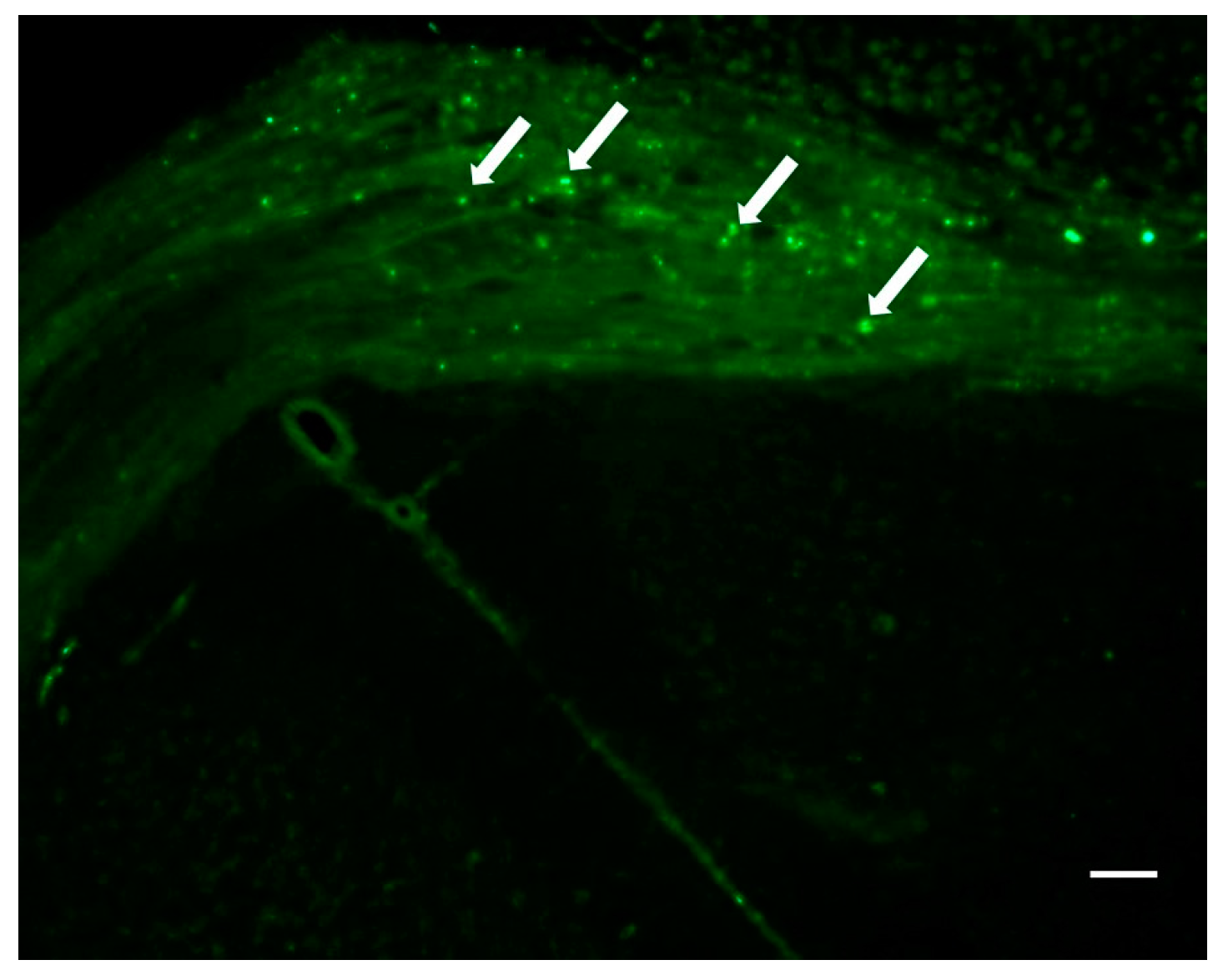

2.3.2. Intracranial Injection of Dendrimers

2.4. Histology

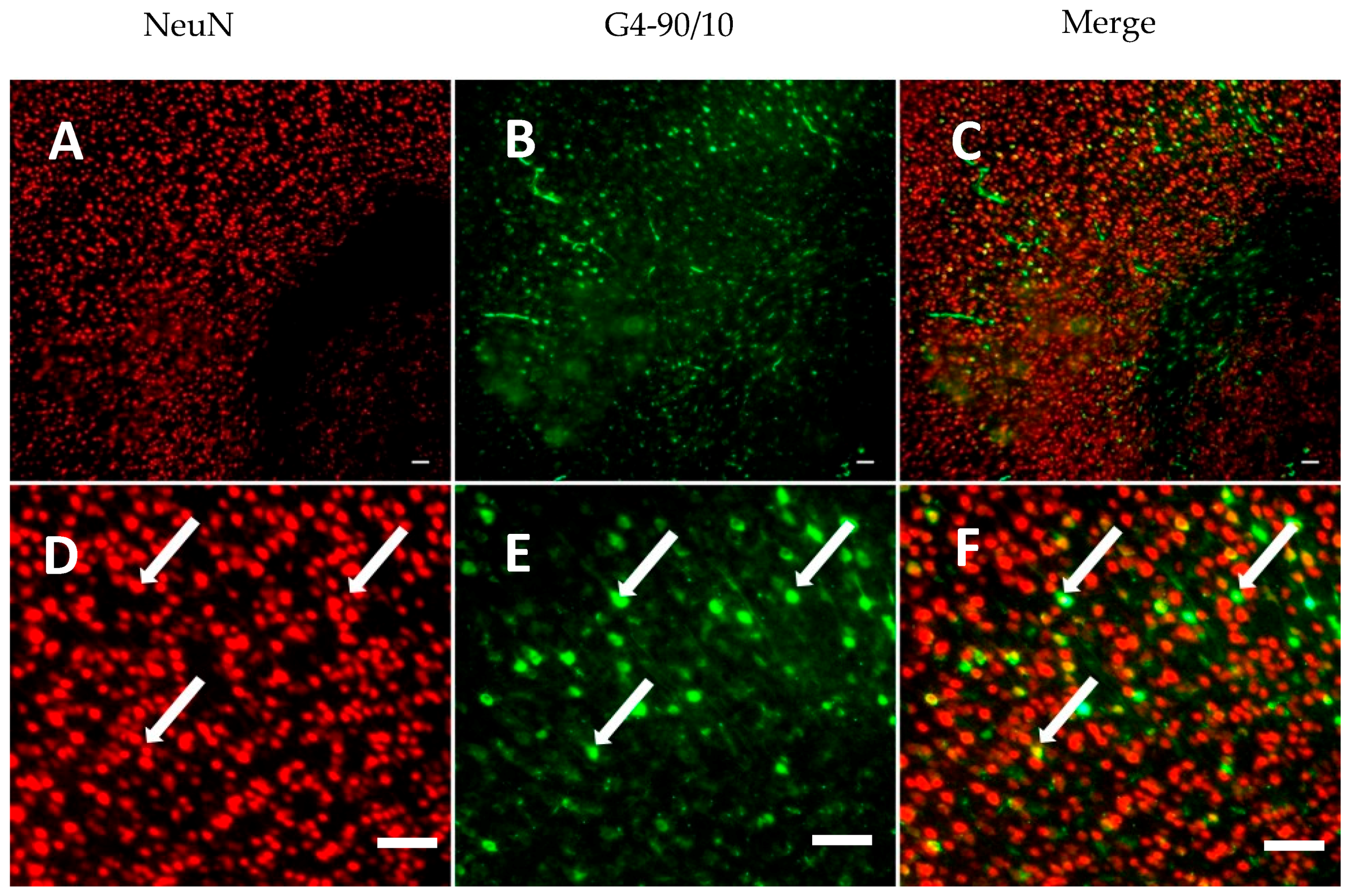

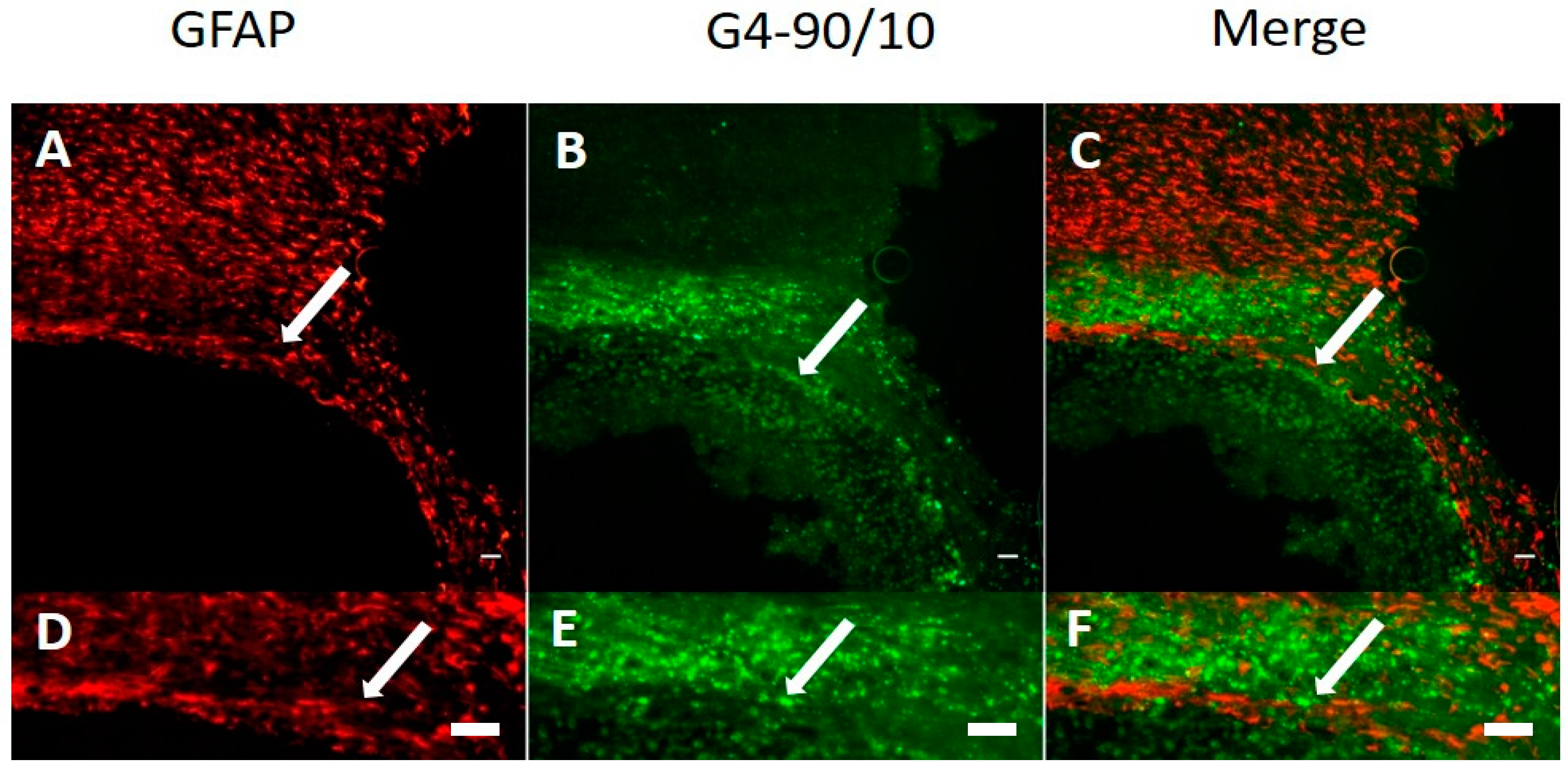

Dendrimer Migration 1-Week Post-Transplantation and Co-Localization with Neurons and Glial Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Dendrimer Synthesis and Characterization

4.1.1. PAMAM Dendrimer Synthesis G1 and G4, DAB Core, 100% NH2 Surface

4.1.2. Preparation of PAMAM Mixed Surface Dendrimer G = 1, DAB Core, 90% OH, 10% NH2 (G1-90/10)

4.1.3. Preparation of PAMAM Mixed Surface Dendrimer G = 4, DAB Core, 90% OH, 10% NH2 (G4-90/10)

4.1.4. Preparation of Dendrimer-FITC Conjugates

4.1.5. Characterization of Dendrimers

4.2. In Vitro

4.2.1. Extraction of Primary Cortical Neurons from Mouse (E18)

4.2.2. Dendrimer Permeability Assay with Primary Cortical Culture

4.3. In Vivo

4.3.1. Animals

4.3.2. Groups

4.3.3. Dendrimer Administration by Intracranial Injection into the Striatum

4.3.4. Dendrimer Administration by Intracarotid Injection through Internal Carotid Artery

4.4. Histology

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| CCA | Common carotid artery |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| DAB | Diaminobutane |

| DMF | Dimethylformamide |

| ECA | External carotid artery |

| EDA | Ethylenediamine |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| HBSS | Hank’s balanced salt solution |

| ICA | Internal carotid artery |

| IEF | Isoelectric focusing |

| MEM | minimum essential medium |

| MWCO | Molecular weight cut-off |

| MW | Molecular weight |

| NEAA | Non-essential amine acids |

| NeuN | Neuronal nuclei |

| P/S | Penicillin streptomycin |

| PAMAM | Poly-amidoamine |

| PAGE | Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| PBS | Phosphate buffered saline |

| PCN | Primary cortical neurons |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| pI | Isoelectric points |

| PI | Propidium iodide |

| RP-HPLC | Reverse phase-high performance liquid chromatography |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic acid |

| TLC | Thin layer chromatography |

| UV | Ultra-violet |

References

- Tripathy, S.; Das, M.K. Dendrimers and their Applications as Novel Drug Delivery Carriers. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 3, 142–149. [Google Scholar]

- Newkome, G.R.; Carol, D.S. Poly(amidoamine), Polypropylenimine, and Related Dendrimers and Dendrons Possessing Different 1 → 2 Branching Motifs: An Overview of the Divergent Procedures. Polymer 2008, 49, 1–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukowska-Latallo, J.F.; Candido, K.A.; Cao, Z.; Nigavekar, S.S.; Majoros, I.J.; Thomas, T.P.; Balogh, L.P.; Khan, M.K.; Baker, J.R., Jr. Nanoparticle Targeting of Anticancer Drug Improves Therapeutic Response in Animal Model of Human Epithelial Cancer. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 5317–5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayder, M.; Fruchon, S.; Fournié, J.J.; Poupot, M.; Poupot, R. Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Dendrimers per Se. Sci. World J. 2011, 11, 1367–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, F.; Guzman, L. Dendrimer Nanocarriers Drug Action: Perspective for Neuronal Pharmacology. Neural Regen. Res. 2015, 10, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vögtle, F. Dendrimers II: Architecture, Nanostructure and Supramolecular Chemistry. In Topics in Current Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Albertazzi, L.; Gherardini, L.; Brondi, M.; Sulis, S.S.; Bifone, A.; Pizzorusso, T.; Ratto, G.M.; Bardi, G. In vivo Distribution and Toxicity of PAMAM Dendrimers in the Central Nervous System Depend on Their Surface Chemistry. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichman, J.D.; Bielinska, A.U.; Kukowska-Latallo, J.F.; Baker, J.R., Jr. The Use of PAMAM Dendrimers in the Efficient Transfer of Genetic Material into Cells. Pharm. Sci. Technol. Today 2000, 3, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaney, J.; Campbell, M. The Dynamic Blood–brain Barrier. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 4067–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, W.A. Characteristics of Compounds That Cross the Blood–Brain Barrier. BMC Neurol. 2009, 9, S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, K.K. Nanobiotechnology-Based Strategies for Crossing the Blood–Brain Barrier. Nanomedicine 2012, 7, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storm, P.B.; Moriarity, J.L.; Tyler, B.; Burger, P.C.; Brem, H.; Weingart, J. Polymer Delivery of Camptothecin against 9L Gliosarcoma: Release, Distribution, and Efficacy. J. Neurooncol. 2002, 56, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barchet, T.M.; Amiji, M.M. Challenges and Opportunities in CNS Delivery of Therapeutics for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2009, 6, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertero, A.; Boni, A.; Gemmi, M.; Gagliardi, M.; Bifone, A.; Bardi, G. Surface Functionalisation Regulates Polyamidoamine Dendrimer Toxicity on Blood–Brain Barrier Cells and the Modulation of Key Inflammatory Receptors on Microglia. Nanotoxicology 2014, 8, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.I.; Beg, S.; Samad, A.; Baboota, S.; Kohli, K.; Ali, J.; Ahuja, A.; Akbar, M. Strategy for Effective Brain Drug Delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 40, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.; Meyers, P.M.; Ornstein, E. Intracarotid Delivery of Drugs: The Potential and the Pitfalls. Anesthesiology 2008, 109, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.; Emala, C.W.; Pile-Spellman, J. Intra-Arterial Drug Delivery: A Concise Review. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 2007, 19, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Stefano, D.; Carnuccio, R.; Maiuri, M.C. Nanomaterials Toxicity and Cell Death Modalities. J. Drug Deliv. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, T.P.; Majoros, I.; Kotlyar, A.; Mullen, D.; Holl, M.M.; Baker, J.R., Jr. Cationic poly (amidoamine) dendrimer induces lysosomal apoptotic pathway at therapeutically relevant concentrations. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 3207–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, H.; Guo, F.; Rao, S.; Deng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, Y.; Guo, C.; et al. PAMAM nanoparticles promote acute lung injury by inducing autophagic cell death through the Akt-TSC2-mTOR signaling pathway. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 1, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Márquez-Miranda, V.; Peñaloza, J.P.; Araya-Durán, I.; Reyes, R.; Vidaurre, S.; Romero, V.; Fuentes, J.; Céric, F.; Velásquez, L.; González-Nilo, F.D.; et al. Effect of Terminal Groups of Dendrimers in the Complexation with Antisense Oligonucleotides and Cell Uptake. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannan, R.M.; Nance, E.; Kannan, S.; Tomalia, D.A. Emerging concepts in dendrimer-based nanomedicine: From design principles to clinical applications. J. Intern. Med. 2014, 276, 579–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, T.; Ravizzini, G.; Choyke, P.L.; Kobayashi, H. Dendrimers in medical nanotechnology. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. 2009, 28, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, N.; Kobayashi, H.; Saga, T.; Nakamoto, Y.; Ishimori, T.; Togashi, K.; Fujibayash, Y.; Konishi, J.; Brechbiel, M.W. Tumor targeting and imaging of intraperitoneal tumors by use of antisense oligo-DNA complexed with dendrimers and/or avidin in mice. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001, 7, 3606–3612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lesniak, W.G.; Mishra, M.K.; Jyoti, A.; Balakrishnan, B.; Zhang, F.; Nance, E.; Romero, R.; Kannan, S.; Kannan, R.M. Biodistribution of Fluorescently Labeled PAMAM Dendrimers in Neonatal Rabbits: Effect of Neuroinflammation. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 4560–4571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomalia, D.A.; Christensen, J.B.; Boas, U. Dendrimers, Dendrons and Dendritic Polymers: Discovery, Applications, and the Future; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Desai, A.; Ali, R.; Tomalia, D. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis separation and detection of polyamidoamine dendrimers possessing various cores and terminal groups. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1081, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhaya, S.K.; Swanson, D.R.; Tomalia, D.A.; Sharma, A. Analysis of Polyamidoamine Dendrimers by Isoelectric Focusing. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Srinageshwar, B.; Peruzzaro, S.; Andrews, M.; Johnson, K.; Hietpas, A.; Clark, B.; McGuire, C.; Petersen, E.; Kippe, J.; Stewart, A.; et al. PAMAM Dendrimers Cross the Blood–Brain Barrier When Administered through the Carotid Artery in C57BL/6J Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18030628

Srinageshwar B, Peruzzaro S, Andrews M, Johnson K, Hietpas A, Clark B, McGuire C, Petersen E, Kippe J, Stewart A, et al. PAMAM Dendrimers Cross the Blood–Brain Barrier When Administered through the Carotid Artery in C57BL/6J Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017; 18(3):628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18030628

Chicago/Turabian StyleSrinageshwar, Bhairavi, Sarah Peruzzaro, Melissa Andrews, Kayla Johnson, Allison Hietpas, Brittany Clark, Crystal McGuire, Eric Petersen, Jordyn Kippe, Andrew Stewart, and et al. 2017. "PAMAM Dendrimers Cross the Blood–Brain Barrier When Administered through the Carotid Artery in C57BL/6J Mice" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, no. 3: 628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18030628