Is There a Role for Genomics in the Management of Hypertension?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Monogenic Forms of Hypertension

3. Large-Scale Genome-Wide Associations Studies

4. Epigenetic Modifications in Hypertensive Patients

5. Pharmacogenomics

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Piepoli, M.F.; Hoes, A.W.; Agewall, S.; Albus, C.; Brotons, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Cooney, M.T.; Corrà, U.; Cosyns, B.; Deaton, C.; et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2315–2381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Benjamin, E.J.; Go, A.S.; Arnett, D.K.; Blaha, M.J.; Cushman, M.; de Ferranti, S.; Després, J.P.; Fullerton, H.J.; Howard, V.J.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 Update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015, 131, e29–e322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hottenga, J.J.; Boomsma, D.I.; Kupper, N.; Posthuma, D.; Snieder, H.; Willemsen, G.; de Geus, E.J. Heritability and stability of resting blood pressure. Twin. Res. Hum. Genet. 2005, 8, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miall, W.E.; Oldham, P. The hereditary factor in arterial blood-pressure. Br. Med. J. 1963, 1, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.J. The causes of essential hypertension. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1996, 42, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, R.R.; Hunt, S.C.; Hopkins, P.N.; Wu, L.L.; Hasstedt, S.J.; Berry, T.D.; Barlow, G.K.; Stults, B.M.; Schumacher, M.C.; Ludwig, E.H.; et al. Genetic basis of familial dyslipidemia and hypertension: 15-year results from Utah. Am. J. Hypertens. 1993, 6, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, S.; Caulfield, M.; Dominiczak, A.F. Genetic and molecular aspects of hypertension. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 937–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munroe, P.B.; Barnes, M.R.; Caulfield, M.J. Advances in blood pressure genomics. Circ. Res. 2013, 112, 1365–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper-DeHoff, R.M.; Johnson, J.A. Hypertension pharmacogenomics: In search of personalized treatment approaches. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, I.A.; Charchar, F.J. Epigenetic Modifications in Essential Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lifton, R.P.; Gharavi, A.G.; Geller, D.S. Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension. Cell 2001, 104, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehret, G.B.; Caulfield, M.J. Genes for blood pressure: An opportunity to understand hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lifton, R.P.; Dluhy, R.G.; Powers, M.; Rich, G.M.; Cook, S.; Ulick, S.; Lalouel, J.M. A chimaeric 11β-hydroxylase/aldosterone synthase gene causes glucocorticoid-remediable aldosteronism and human hypertension. Nature 1992, 355, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stowasser, M. Update in primary aldosteronism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.; Scholl, U.I.; Yue, P.; Björklund, P.; Zhao, B.; Nelson-Williams, C. K+ channel mutations in adrenal aldosterone-producing adenomas and hereditary hypertension. Science 2011, 331, 768–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholl, U.I.; Stölting, G.; Nelson-Williams, C.; Vichot, A.A.; Choi, M.; Loring, E.; Prasad, M.L.; Goh, G.; Carling, T.; Juhlin, C.C.; et al. Recurrent gain of function mutation in calcium channel CACNA1H causes early-onset hypertension with primary aldosteronism. eLife 2015, 4, e06315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniil, G.; Fernandes-Rosa, F.L.; Chemin, J.; Blesneac, I.; Beltrand, J.; Polak, M. CACNA1H Mutations Are Associated With Different Forms of Primary Aldosteronism. EBioMedicine 2016, 13, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes-Rosa, F.L.; Williams, T.A.; Riester, A.; Steichen, O.; Beuschlein, F.; Boulkroun, S. Genetic spectrum and clinical correlates of somatic mutations in aldosterone-producing adenoma. Hypertension 2014, 64, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monticone, S.; Else, T.; Mulatero, P.; Williams, T.A.; Rainey, W.E. Understanding primary aldosteronism: Impact of next generation sequencing and expression profiling. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015, 399, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholl, U.I.; Goh, G.; Stolting, G.; de Oliveira, R.C.; Choi, M.; Overton, J.D.; Fonseca, A.L.; Korah, R.; Starker, L.F.; Kunstman, J.W.; et al. Somatic and germline CACNA1D calcium channel mutations in aldosterone-producing adenomas and primary aldosteronism. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1050–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulick, S.; Levine, L.S.; Gunczler, P.; Zanconato, G.; Ramirez, L.C.; Rauh, W. A syndrome of apparent mineralocorticoid excess associated with defects in the peripheral metabolism of cortisol. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1979, 49, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funder, J.W. Apparent mineralocorticoid excess. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 65, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, J.E.; Healy, J.K. Hyperkalemia, hypertension and systemic acidosis without renal failure associated with a tubular defect in potassium excretion. Am. J. Med. 1969, 47, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowasser, M.; Gordon, R.D. Primary Aldosteronism: Changing Definitions and New Concepts of Physiology and Pathophysiology Both Inside and Outside the Kidney. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 1327–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, F.H.; Disse-Nicodème, S.; Choate, K.A.; Ishikawa, K.; Nelson-Williams, C.; Desitter, I.; Gunel, M.; Milford, D.V.; Lipkin, G.W.; Achard, J.M.; et al. Human hypertension caused by mutations in WNK kinases. Science 2001, 293, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyden, L.M.; Choi, M.; Choate, K.A.; Nelson-Williams, C.J.; Farhi, A.; Toka, H.R.; Tikhonova, I.R.; Bjornson, R.; Mane, S.M.; Colussi, G.; et al. Mutations in kelch-like 3 and cullin 3 cause hypertension and electrolyte abnormalities. Nature 2012, 482, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathare, G.; Hoenderop, J.G.; Bindels, R.J.; San-Cristobal, P. A molecular update on pseudohypoaldosteronism type II. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2013, 305, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashmi, P.; Colussi, G.; Ng, M.; Wu, X.; Kidwai, A.; Pearce, D. Glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper protein regulates sodium and potassium balance in the distal nephron. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 1159–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, P.M. The epithelial Na+ channel: Cell surface insertion and retrieval in Na+ homeostasis and hypertension. Endocr. Rev. 2002, 23, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansson, J.H.; Nelson-Williams, C.; Suzuki, H.; Schild, L.; Shimkets, R.; Lu, Y. Hypertension caused by a truncated epithelial sodium channel gamma subunit: Genetic heterogeneity of Liddle syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1995, 11, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimkets, R.A.; Warnock, D.G.; Bositis, C.M.; Nelson-Williams, C.; Hansson, J.H.; Schambelan, M. Liddle’s syndrome: Heritable human hypertension caused by mutations in the β subunit of the epithelial sodium channel. Cell 1994, 79, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcu, A.F.; Auchus, R.J. Adrenal steroidogenesis and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 44, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biglieri, E.G.; Kater, C.E. Mineralocorticoids in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1991, 40, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portrat, S.; Mulatero, P.; Curnow, K.M.; Chaussain, J.L.; Morel, Y.; Pascoe, L. Deletion hybrid genes, due to unequal crossing over between CYP11B1 (11β-hydroxylase) and CYP11B2 (aldosterone synthase) cause steroid 11β -hydroxylase deficiency and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 3197–3201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schuster, H.; Wienker, T.E.; Bähring, S.; Bilginturan, N.; Toka, H.R.; Neitzel, H. Severe autosomal dominant hypertension and brachydactyly in a unique Turkish kindred maps to human chromosome 12. Nat. Genet. 1996, 13, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maass, P.G.; Aydin, A.; Luft, F.C.; Schächterle, C.; Weise, A.; Stricker, S. PDE3A mutations cause autosomal dominant hypertension with brachydactyly. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toka, O.; Tank, J.; Schächterle, C.; Aydin, A.; Maass, P.G.; Elitok, S. Clinical effects of phosphodiesterase 3A mutations in inherited hypertension with brachydactyly. Hypertension 2015, 66, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, D.S.; Farhi, A.; Pinkerton, N.; Fradley, M.; Moritz, M.; Spitzer, A.; Meinke, G.; Tsai, F.T.; Sigler, P.B.; Lifton, R.P. Activating mineralocorticoid receptor mutation in hypertension exacerbated by pregnancy. Science 2000, 289, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafestin-Oblin, M.E.; Souque, A.; Bocchi, B.; Pinon, G.; Fagart, J.; Vandewalle, A. The severe form of hypertension caused by the activating S810L mutation in the mineralocorticoid receptor is cortisone related. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opocher, G.; Schiavi, F. Genetics of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 24, 943–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welander, J.; Söderkvist, P.; Gimm, O. Genetics and clinical characteristics of hereditary pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2011, 18, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachidanandam, R.; Weissman, D.; Schmidt, S.C.; Kakol, J.M.; Stein, L.D.; Marth, G.; Sherry, S.; Mullikin, J.C.; Mortimore, B.J.; Willey, D.L.; et al. A map of human genome sequence variation containing 1.42 million single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nature 2001, 409, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altshuler, D.; Daly, M.J.; Lander, E.S. Genetic mapping in human disease. Science 2008, 322, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munroe, P.B.; Wallace, C.; Xue, M.Z.; Marcano, A.C.; Dobson, R.J.; Onipinla, A.K.; Burke, B.; Gungadoo, J.; Newhouse, S.J.; Pembroke, J.; et al. Increased support for linkage of a novel locus on chromosome 5q13 for essential hypertension in the British Genetics of Hypertension Study. Hypertension 2006, 48, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.P.; Liu, X.; Kim, J.D.; Ikeda, M.A.; Layton, M.R.; Weder, A.B.; Cooper, R.S.; Kardia, S.L.; Rao, D.C.; Hunt, S.C.; et al. Multiple genes for essential-hypertension susceptibility on chromosome 1q. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 80, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehret, G.B.; O’Connor, A.A.; Weder, A.; Cooper, R.S.; Chakravarti, A. Follow-up of a major linkage peak on chromosome 1 reveals suggestive QTLs associated with essential hypertension: GenNet study. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 17, 1650–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croteau-Chonka, D.C.; Rogers, A.J.; Raj, T.; McGeachie, M.J.; Qiu, W.; Ziniti, J.P.; Stubbs, B.J.; Liang, L.; Martinez, F.D.; Strunk, R.C.; et al. Expression Quantitative Trait Loci Information Improves Predictive Modelling of Disease Relevance of Non-Coding Genetic Variation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risch, N.; Merikangas, K. The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases. Science 1996, 273, 1516–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehret, G.B.; Munroe, P.B.; Rice, K.M.; Bochud, M.; Johnson, A.D.; Chasman, D.I.; Smith, A.V.; Tobin, M.D.; Verwoert, G.C.; Hwang, S.J.; et al. Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Nature 2011, 478, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International HapMap Consortium. A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature 2005, 437, 1299–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, D.; Lander, S. On the allelic spectrum of human disease. Trends Genet. 2001, 17, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3000 shared controls. Nature 2007, 447, 661–678. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, T.; Gaunt, T.R.; Newhouse, S.J.; Padmanabhan, S.; Tomaszewski, M.; Kumari, M.; Morris, R.W.; Tzoulaki, I.; O’Brien, E.T.; Poulter, N.R.; et al. Blood pressure loci identified with a gene-centric array. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 89, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Jaramillo, P.; Camacho, P.A.; Forero-Naranjo, L. The role of environment and epigenetics in hypertension. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2013, 11, 1455–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raftopoulos, L.; Katsi, V.; Makris, T.; Tousoulis, D.; Stefanadis, C.; Kallikazaros, I. Epigenetics, the missing link in hypertension. Life Sci. 2015, 129, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loscalzo, J.; Handy, D.E. Epigenetic modifications: Basic mechanisms and role in cardiovascular disease (2013 grover conference series). Pulm. Circ. 2014, 4, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolarek, I.; Wyszko, E.; Barciszewska, A.M.; Nowak, S.; Gawronska, I.; Jablecka, A.; Barciszewska, M.Z. Global DNA methylation changes in blood of patients with essential hypertension. Med. Sci. Monit. Basic. Res. 2010, 16, 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Friso, S.; Pizzolo, F.; Choi, S.-W.; Guarini, P.; Castagna, A.; Ravagnani, V.; Carletto, A.; Pattini, P.; Corrocher, R.; Olivieri, O.; et al. Epigenetic control of 11 β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 gene promoter is related to human hypertension. Atherosclerosis 2008, 199, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, R.; Goyal, D.; Leitzke, A.; Gheorghe, C.P.; Longo, L.D. Brain renin-angiotensin system: Fetal epigenetic programming by maternal protein restriction during pregnancy. Reprod. Sci. 2010, 17, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.A.; Baek, I.; Seok, Y.M.; Yang, E.; Cho, H.M.; Lee, D.Y.; Hong, S.H.; Kim, I.K. Promoter hypomethylation upregulates Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 1 in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 396, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, F.; Wang, X.; Yue, R.; Chen, C.; Huang, J.; Huang, J.; Li, X.; Zeng, C. Differential expression and DNA methylation of angiotensin type 1A receptors in vascular tissues during genetic hypertension development. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 402, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivière, G.; Lienhard, D.; Andrieu, T.; Vieau, D.; Frey, B.M.; Frey, F.J. Epigenetic regulation of somatic angiotensin-converting enzyme by DNA methylation and histone acetylation. Epigenetics 2011, 6, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fish, J.E.; Matouk, C.C.; Rachlis, A.; Lin, S.; Tai, S.C.; D’Abreo, C.; Marsden, P.A. The expression of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase is controlled by a cell-specific histone code. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 4824–4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.A.; Cho, H.M.; Lee, D.Y.; Kim, K.C.; Han, H.S.; Kim, I.K. Tissue-specific upregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 1 in spontaneously hypertensive rats through histone code modifications. Hypertension 2012, 59, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.M.; Lee, D.Y.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, H.A.; Seok, Y.M.; Kim, I.K. Upregulation of the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 1 via histone modification in the aortas of angiotensin II-induced hypertensive rats. Hypertens. Res. 2012, 35, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, S.; Shimosawa, T.; Ogura, S.; Wang, H.; Uetake, Y.; Kawakami-Mori, F.; Marumo, T.; Yatomi, Y.; Geller, D.S.; Tanaka, H.; et al. Epigenetic modulation of the renal β-adrenergic-WNK4 pathway in salt-sensitive hypertension. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.; Liu, T.; Jiang, F.; Liu, C.; Zhao, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z. MicroRNA-155 regulates angiotensin II type 1 receptor expression in umbilical vein endothelial cells from severely pre-eclamptic pregnant women. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2011, 27, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marques, F.Z.; Campain, A.E.; Tomaszewski, M.; Zukowska-Szczechowska, E.; Yang, Y.H.J.; Charchar, F.J.; Morris, B.J. Gene expression profiling reveals renin mRNA overexpression in human hypertensive kidneys and a role for microRNAs. Hypertension 2011, 58, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, P.; Wu, C.; Khan, A.M.; Bloch, D.B.; Davis-Dusenbery, B.N.; Ghorbani, A. Atrial natriuretic peptide is negatively regulated by microRNA-425. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 3378–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenuwein, T.; Allis, C.D. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001, 293, 1074–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millis, R.M. Epigenetics and hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2011, 13, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huntzinger, E.; Izaurralde, E. Gene silencing by microRNAs: Contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethupathy, P.; Borel, C.; Gagnebin, M.; Grant, G.R.; Deutsch, S.; Elton, T.S.; Hatzigeorgiou, A.G.; Antonarakis, S.E. Human microRNA-155 on chromosome 21 differentially interacts with its polymorphic target in the AGTR1 31 untranslated region: A mechanism for functional single-nucleotide polymorphisms related to phenotypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voora, D.; Ginsburg, G.S. Clinical application of cardiovascular pharmacogenetics. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frau, F.; Zaninello, R.; Salvi, E.; Ortu, M.F.; Braga, D.; Velayutham, D. Genome-wide association study identifies CAMKID variants involved in blood pressure response to losartan: The SOPHIA study. Pharmacogenomics 2014, 15, 1643–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagato, L.; Modica, R.; Florio, M.; Bihoreau, M.T.; Bianchi, G.; Tripodi, G. Genetic mapping of blood pressure quantitative trait loci in Milan hypertensive rats. Hypertension 2000, 36, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, G.; Ferrari, P.; Staessen, J.A. Adducin polymorphism: Detection and impact on hypertension and related disorders. Hypertension 2005, 45, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staessen, J.A.; Bianchi, G. Adducin and hypertension. Pharmacogenomics 2005, 6, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staessen, J.A.; Thijs, L.; Stolarz-Skrzypek, K.; Bacchieri, A.; Barton, J.; Espositi, E.D.; de Leeuw, P.W.; Dłużniewski, M.; Glorioso, N.; Januszewicz, A.; et al. Main results of the ouabain and adducin for Specific Intervention on Sodium in Hypertension Trial (OASIS-HT): A randomized placebo-controlled phase-2 dose-finding study of rostafuroxin. Trials 2011, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmanabhan, S.; Melander, O.; Johnson, T.; Di Blasio, A.M.; Lee, W.K.; Gentilini, D.; Global BPgen Consortium. Genome-wide association study of blood pressure extremes identifies variant near UMOD associated with hypertension. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmanabhan, S.; Graham, L.; Ferreri, N.R.; Graham, D.; McBride, M.; Dominiczak, A.F. Uromodulin, an emerging novel pathway for blood pressure regulation and hypertension. Hypertension 2014, 64, 918–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, L.A.; Padmanabhan, S.; Fraser, N.J.; Kumar, S.; Bates, J.M.; Raffi, H.S.; Welsh, P.; Beattie, W.; Hao, S.; Leh, S.; et al. Validation of uromodulin as a candidate gene for human essential hypertension. Hypertension 2014, 63, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trudu, M.; Janas, S.; Lanzani, C.; Debaix, H.; Schaeffer, C.; Ikehata, M.; Swiss Kidney Project on Genes in Hypertension (SKIPOGH) Team. Common noncoding UMOD gene variants induce salt-sensitive hypertension and kidney damage by increasing uromodulin expression. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menni, C. Blood pressure pharmacogenomics: Gazing into a misty crystal ball. J. Hypertens. 2015, 33, 1142–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlberg, J.; Nilsson, L.O.; von Wowern, F.; Melander, O. Polymorphism in NEDD4L is associated with increased salt sensitivity, reduced levels of P-renin and increased levels of Nt-proANP. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, J.D.; Turner, S.T.; Tran, B.; Chapman, A.B.; Bailey, K.R.; Gong, Y.; Gums, J.G.; Langaee, T.Y.; Beitelshees, A.L.; Cooper-Dehoff, R.M.; et al. Association of chromosome 12 locus with antihypertensive response to hydrochlorothiazide may involve differential YEATS4 expression. Pharmacogenom. J. 2013, 13, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chittani, M.; Zaninello, R.; Lanzani, C.; Frau, F.; Ortu, M.F.; Salvi, E. TET2 and CSMD1 genes affect SBP response to hydrochlorothiazide in never-treated essential hypertensives. J. Hypertens. 2015, 33, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvi, E.; Wang, Z.; Rizzi, F.; Gong, Y.; McDonough, CW.; Padmanabhan, S.; Hiltunen, T.P.; Lanzani, C.; Zaninello, R.; Chittani, M.; et al. Genome-Wide and Gene-Based Meta-Analyses Identify Novel Loci Influencing Blood Pressure Response to Hydrochlorothiazide. Hypertension 2017, 69, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesh, S.K.; Tragante, V.; Guo, W.; Guo, Y.; Lanktree, M.B.; Smith, E.N.; Johnson, T.; Castillo, B.A.; Barnard, J.; Baumert, J.; et al. Loci influencing blood pressure identified using a cardiovascular gene-centric array. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 1663–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mialet Perez, J.; Rathz, D.A.; Petrashevskaya, N.N.; Hahn, H.S.; Wagoner, L.E.; Schwartz, A. β 1-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms confer differential function and predisposition to heart failure. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 1300–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, J.; Lind, L.; Hallberg, P.; Michaëlsson, K.; Kurland, L.; Kahan, T.; Malmqvist, K.; Ohman, K.P.; Nyström, F.; Melhus, H. β1-adrenergic receptor gene polymorphisms and response to β1-adrenergic receptor blockade in patients with essential hypertension. Clin. Cardiol. 2004, 27, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rau, T.; Heide, R.; Bergmann, K.; Wuttke, H.; Werner, U.; Feifel, N.; Eschenhagen, T. Effect of the CYP2D6 genotype on metoprolol metabolism persists during long-term treatment. Pharmacogenetics 2002, 12, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, V.; O’Connor, D.T.; Brophy, V.H.; Schork, N.J.; Richard, E.; Salem, R.M.; Nievergelt, C.M.; Bakris, G.L.; Middleton, J.P.; AASK Study Investigators; et al. G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 4 polymorphisms and blood pressure response to metoprolol among African Americans: Sex-specificity and interactions. Am. J. Hypertens. 2009, 22, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannila-Handelberg, T.; Kontula, K.; Tikkanen, I.; Tikkanen, T.; Fyhrquist, F.; Helin, K.; Fodstad, H.; Piippo, K.; Miettinen, H.E.; Virtamo, J.; et al. Common variants of the β and gamma subunits of the epithelial sodium channel and their relation to plasma renin and aldosterone levels in essential hypertension. BMC Med. Genet. 2005, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Monogenic Syndrome | Inheritance | Gene | Locus | Phenotype | Therapeutic Indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pheochromocytomas/Paragangliomas | Autosomal dominant | SDHA SDHB SDHC SDHD SDHAF2 TMEM127 MAX | 5p15.3 1p36.13 1q23.3 11q23.1 11q12.2 2q11.2 14q23.3 | Paragangliomas or pheochromocytomas. | Surgery/α adrenergic blockers |

| von Hippel–Lindau syndrome | Autosomal dominant | VHL | 3p25.3 | Retinal, cerebellar and spinal hemangioblastoma, renal cell carcinoma, pheochromocytomas, pancreatic tumours. | Surgery/α adrenergic blockers (for pheochromocytoma) |

| Multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 2A | Autosomal dominant | RET | 10q11.2 | Medullary thyroid carcinoma, parathyroid adenomas, pheochromocytoma. | Surgery/α adrenergic blockers (for pheochromocytoma) |

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 | Autosomal dominant | NF1 | 17q11.2 | Skin pigmentation, skin neurofibromas and brain tumours. Pheochromocytoma. | Surgery/α adrenergic blockers (for pheochromocytoma) |

| GRA–familial hyperaldosteronism type 1 | Autosomal dominant | CYP11B1 CYP11B2 | 8q24.3 | Familial form of PA | Glucocorticoids |

| Familial hyperaldosteronism type 2 | Autosomal dominant | N.A. | 7p22.3-7p22.1 | Familial form of PA | Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist/unilateral adrenalectomy (for APA) |

| Familial hyperaldosteronism type 3 | Autosomal dominant | KCNJ5 | 8q24.3 | Severe form of PA with bilateral adrenal hyperplasia | Bilateral adrenalectomy in drug-resistant patients |

| Familial hyperaldosteronism type 4 | Autosomal dominant | CACNA1H | 16p13.3 | Familial form of PA | Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist |

| PASNA syndrome | N.A. | CACNA1D | 3p21.3 | PA and complex neurological disorders (seizures and functional neurological abnormalities, resembling cerebral palsy). | N.A. |

| Sporadic APA | N.A. | KCNJ5 ATP1A1 ATP2B3 CACNA1D | 11q24.3 1p31.1 Xq28 3p21.3 | Sporadic forms of PA. | Adrenalectomy |

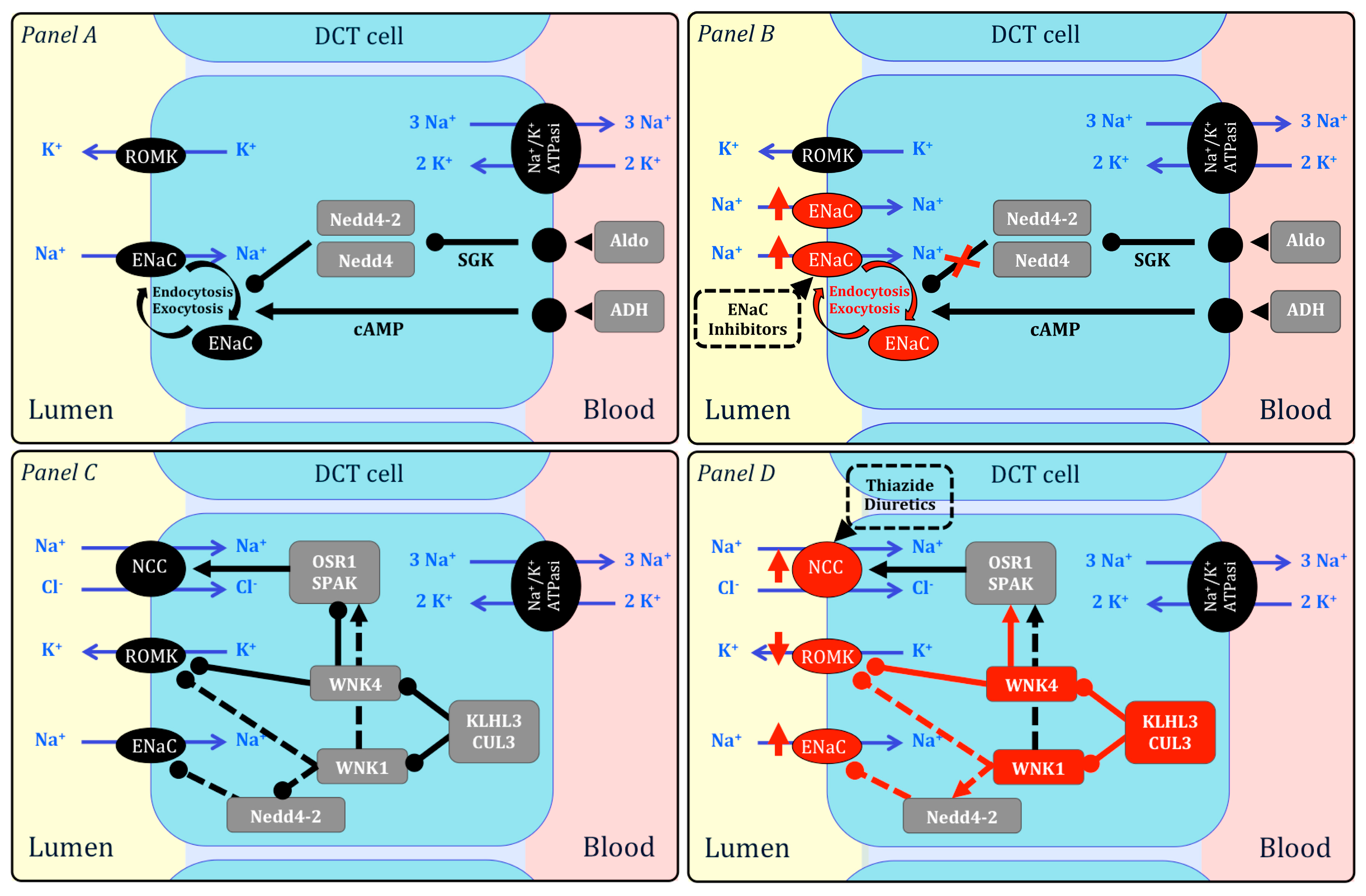

| Pseudohypoaldosteronism, type 2 (Gordon’s syndrome) | Autosomal dominant (*dominant/recessive) | WNK1 WNK4 CUL3 KLHL3 * | 12p12.3 17q21.2 2q36.2 5q31.2 | HyperK+ hyperCl− metabolic acidosis. Low PRA and low-normal AC. | Thiazide diuretics |

| Apparent mineralocorticoid excess (AME) Syndrome | Autosomal recessive | HSD11B2 | 16q22.1 | Hypokalemia. Low PRA and AC. Increased cortisol/cortisone ratio. | Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist |

| Liddle’s syndrome | Autosomal dominant | SCNN1B, SCNN1G | 16p12.2 | ENaC constitutive activation. Hypokalemia. Low PRA and AC. | ENaC blockers (amiloride, triamterene) |

| 11β-hydroxylase deficiency | Autosomal recessive | CYP11B1 | 8q24.3 | Virilisation, short stature. Low PRA and AC. HypoK+ alkalosis. | Glucocorticoids to inhibit ACTH-driven adrenal hyperpasia |

| 17α-hydroxylase deficiency | Autosomal recessive | CYP17A1 | 10q24.3 | HypoK+ alkalosis. Absent sexual maturation. Androgen deficiency. | Glucocorticoids to inhibit ACTH-driven adrenal hyperpasia |

| Hypertension with brachydactyly Type E | Autosomal dominant | PDE3A | 12p12.3 12p12.1 | Brachydactyly, short phalanges and metacarpals. | N.A. |

| Hypertension exacerbated by pregnancy | Autosomal dominant | NR3C2 | 4q31.23 | Early onset hypertension exacerbated during pregnancy. | N.A. |

| SNPs | Nearest Gene(s) | Position | Encoded Protein Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs880315 | CASZ | 1p36.22 | Zinc finger transcription factor that acts as tumour suppressor. |

| rs4846049 | MTHFR(3′)-NPPB | 1p36.22 | MTHFR catalyse the conversion of 5,10-MTH in 5-MTH and it is involved in homocysteine metabolism. NPPB encodes for the B natriuretic peptide. |

| rs17367504 | MTHFR(5′)-NPPB | ||

| rs17030613 | ST7L-CAPZA1 | 1p13.2 | ST7L is a tumour suppressor factor. CAPZA1 regulates growth of actin filaments. |

| rs2932538 | MOV10 | 1p13.2 | A component of the RISC complex RNA helicase. |

| rs2004776 | AGT | 1q42.2 | Pre-angiotensinogen. |

| rs16849225 | FIGN-GRB14 | 2q24.3 | FIGN regulates microtubules synthesis. GRB4 is a growth factor receptor-binding protein, which interacts with insulin receptors and insulin-like growth factors. |

| rs13082711 | SLC4A7 | 3p24.1 | Sodium bicarbonate co-transporter in neuronal cells, involved in visual and auditory transmission. |

| rs3774372 | ULK4 | 3p22.1 | Serine/Threonine kinase involved in neurite branching and elongation and neuronal migration. |

| rs319690 | MAP4 | 3p21.31 | Promotion of microtubule assembly. |

| rs419076 | MECOM | 3q26.2 | Transcriptional regulator and oncoprotein involved in apoptosis, hematopoiesis, cell differentiation and proliferation. |

| rs1458038 | FGF5 | 4q21.21 | Fibroblast growth factor 5, involved in embryonic development, cell growth, morphogenesis, tissue repair, tumour growth and invasion. |

| rs13107325 | SLC39A8 | 4q24 | Mitochondrial cellular import of zinc, involved in inflammation. |

| rs6825911 | ENPEP | 4q25 | Glutamyl aminopeptidase; associated with renal neoplasm. |

| rs13139571 | GUCY1A3-1B3 | 4q32.1 | Guanylate cyclase 1 soluble subunit α, involved in nitric oxide pathway transduction. |

| rs1173771 | NPR3-C5orf23 | 5p13.3 | Natriuretic peptide receptor 3, responsible for clearing natriuretic peptides through endocytosis of the receptor. |

| rs11953630 | EBF1 | 5q33.3 | Early B-cell factor 1, associated with central obesity, B-lymphocytes differentiation and Hodgkin lymphoma. |

| rs1799945 | HFE | 6p22.2 | Hemochromatosis protein; regulation of iron absorption. |

| rs805303 | BAT2-BAT5 | 6p21.33 | Genes cluster localized near genes for TNF α and β, involved in inflammatory process and associated with insulin dependent diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis. |

| rs17477177 | PIK3CG | 7q22.3 | A catalytic subunit of PI3K, involved in the immune response. |

| rs3918226 | NOS3 | 7q36.1 | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase. |

| rs2898290 | BLK-GATA4 | 8p23.1 | BLK is a tyrosine kinase involved in cell proliferation and differentiation. GATA4 is a zinc finger transcription factor involved in embryogenesis and myocardial differentiation and function. |

| rs1799998 | CYP11B2 | 8q24.3 | Aldosterone synthase. |

| rs4373814 | CACNB2(5′) | 10p12.33 | Member of a voltage-gated calcium channel superfamily, associated with Brugada and Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. |

| rs1813353 | CACNB2(3′) | ||

| rs4590817 | C10orf107 | 10q21.2 | Chromosome 10 open reading frame 107. Unknown function. |

| rs932764 | PLCE1 | 10q23.33 | Phospholipase involved in Ras pathway, associated with early onset nephrotic syndrome. |

| rs11191548 | CYP17A1-NT5C2 | 10q24.32 | CYP17A1 is the 17α hydroxylase, involved in the steroidogenic pathway; mutated in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. NT5C2 is a hydrolase involved in purine nucleotides metabolism. |

| rs1801253 | ADRB1 | 10q25.3 | Adrenoreceptor β1, which mediate physiological effects of epinephrine and norepinephrine. |

| rs7129220 | ADM | 11p15.4 | Pre-hormone cleaved in adrenomedullin and pro-adrenomedullin, which act as vasodilator, hormone secretion regulators and angiogenesis promoters. |

| rs381815 | PLEKHA7 | 11p15.2 | Pleckstrin homology domain containing A7 associated with breast carcinomas and glaucoma. |

| rs633185 | FLJ32810-TMEM133 | 11q22.1 | FLJ32810 is a regulator of vascular tone. TMEM133 is a transmembrane protein; unknown function. |

| rs17249754 | ATP2B1 | 12q21.33 | Calcium ATPase with critical role in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis |

| rs3184504 | SH2B3 | 12q24.12 | Signalling activities by growth factor and cytokine receptors; associated with celiac disease and insulin-dependent diabetes. |

| rs11066280 | ALDH2 | 12q24.12 | Mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, involved in the oxidative pathway of alcohol metabolism. |

| rs10850411 | TBX5-TBX3 | 12q24.21 | T-box protein family encoding for transcriptional factors regulating heart and limbs developmental processes. |

| rs1378942 | CYP1A1-ULK3 | 15q24.1 | CYP1A1 is a mono-oxygenases involved in drug catabolism and synthesis of cholesterol, steroid and other lipids. ULK3 is a serine/threonine kinase; unknown function. |

| rs2521501 | FURIN-FES | 15q26.1 | FURIN is a protease, involved in the catabolism of PTH, TGFβ1 and other growth factors. FES is a tyrosine kinase, involved in hematopoiesis and cytokine receptor signalling. |

| rs13333226 | UMOD | 16p12.3 | Regulation of renal sodium handling. See text. |

| rs17608766 | GOSR2 | 17q21.32 | Trafficking membrane protein. |

| rs12940887 | ZNF652 | 17q21.32 | Zinc finger protein, associated with breast and prostate cancer. |

| rs1327235 | JAG1 | 20p12.2 | Hematopoiesis regulation through notch 1 signalling. |

| rs6015450 | GNAS-EDN3 | 20q13.32 | GNAS is a G-protein that activates adenylyl cyclase with a wide variety of cellular responses. EDN3 encode for endothelin 3, implicated also in neural crest-derived cell lineages differentiation. |

| Epigenetic Modification | Findings/Effectors | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| DNA methylation | Amount of 5mC in DNA inversely proportional to BP levels | Smolarek et al. [57] |

| HSD11B2 promoter methylation associated with HTN onset at young age | Friso et al. [58] | |

| RAA system gene hypomethylation associated with HTN in offspring, BP regulation and ACE inhibitor response. | Goyal et al. [59] Pei et al. [61] Rivière et al. [62] | |

| Hypomethylation of SIC2A2 associated with NKCC1 overexpression, Na+ reabsorption and HTN. | Lee et al. [60] | |

| Histones acetylation/deacetylation | Acetylation/deacetylation of endothelial cells nucleosomes regulate eNOS expression | Fish et al. [63] |

| Nucleosomes modifications regulate ACE transcription | Lee et al. [64] | |

| Nucleosomes modifications regulate NKCC1 transcription and sodium renal reabsorption | Cho et al. [65] | |

| WNK4 down-regulation determines histones acetylation and NCC overexpression. | Mu et al. [66] | |

| Non coding RNA | miR-27a and -27b down-regulate ACE1 mRNA | Goyal et al. [59] |

| miR-155 down-regulate AGTR1 mRNA | Cheng et al. [67] | |

| miR-181a and -663 down-regulate renin mRNA and are under-expressed in HTN-patients | Marquez et al. [68] | |

| miR-425 down-regulate NNPA, leading to ANP under-production and salt overload | Arora et al. [69] |

| Genetic Association | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| NEDD4L, PRKCA, GNAS-EDN3, TET2, CSMD1, HSD3B1 | Enhanced response to thiazide diuretics | Dahlberg et al. [85] Duarte et al. [86] Chittani et al. [87] Salvi et al. [88] |

| ADRB1 | Enhanced response to metoprolol | Ganesh et al. [89] |

| ADRB1 | Enhanced response to carvedilol | Mialet-Perez et al. [90] |

| ADRB1 | Greater mortality in patients treated with verapamil than with atenolol | Karlsson et al. [91] |

| CYP2D6 | Decrease in metoprolol clearance | Rau et al. [92] |

| GRK4 | Enhanced response to atenolol | Bhatnagar et al. [93] |

| SIGLEC12, A1BG, F5 | Higher risk of treatment-related adverse CV outcomes in patients treated with CCB | Hannila et al. [94] |

| CAMK1D | Enhanced response to losartan | Frau et al. [75] |

| ADD1 | Enhanced response to rostafuroxin | Staessen et al. [79] |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burrello, J.; Monticone, S.; Buffolo, F.; Tetti, M.; Veglio, F.; Williams, T.A.; Mulatero, P. Is There a Role for Genomics in the Management of Hypertension? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18061131

Burrello J, Monticone S, Buffolo F, Tetti M, Veglio F, Williams TA, Mulatero P. Is There a Role for Genomics in the Management of Hypertension? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017; 18(6):1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18061131

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurrello, Jacopo, Silvia Monticone, Fabrizio Buffolo, Martina Tetti, Franco Veglio, Tracy A. Williams, and Paolo Mulatero. 2017. "Is There a Role for Genomics in the Management of Hypertension?" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, no. 6: 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18061131