The Role of Hemoproteins: Hemoglobin, Myoglobin and Neuroglobin in Endogenous Thiosulfate Production Processes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

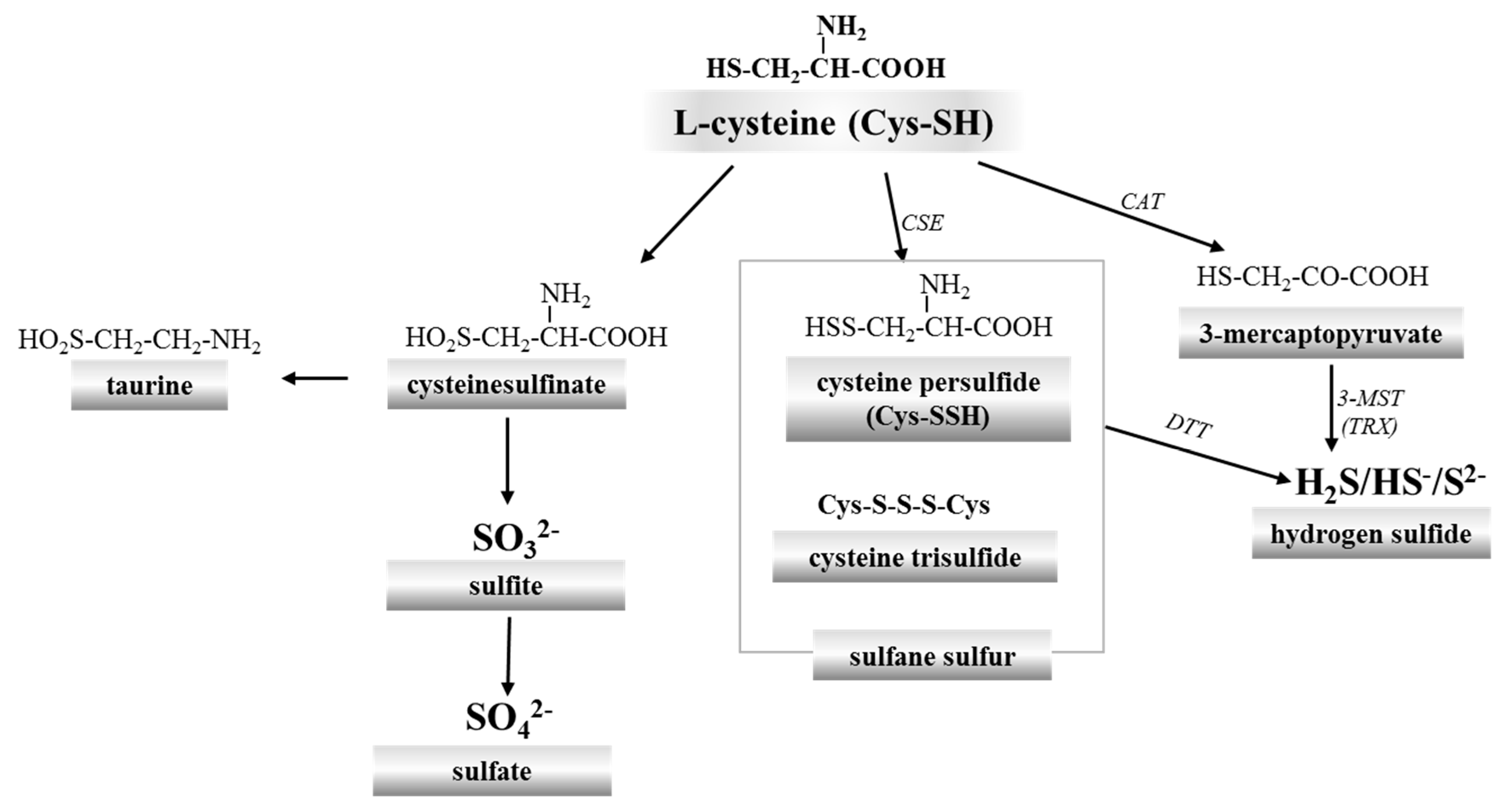

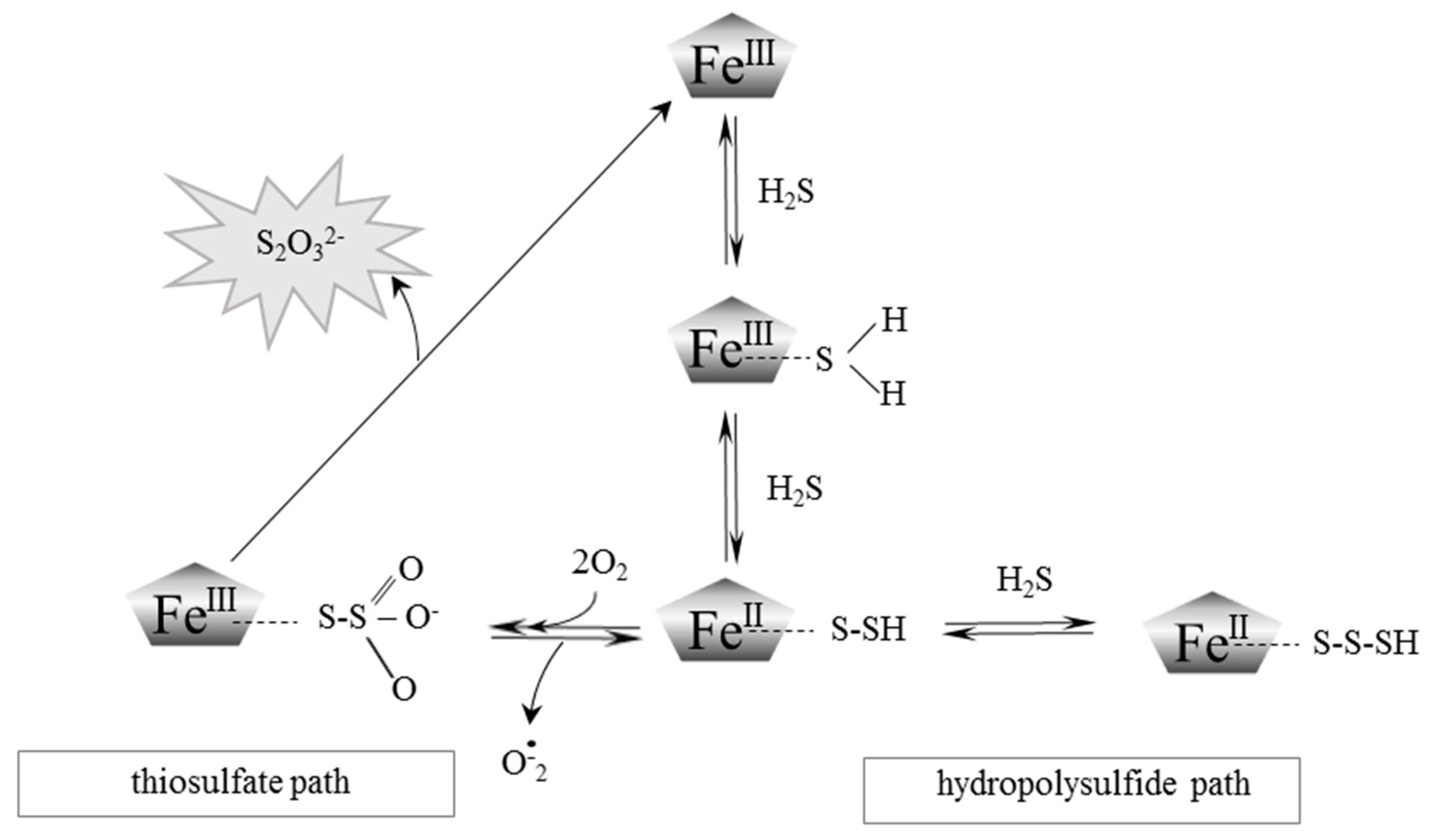

2. Red Blood Cells, Hemoglobin and Hydrogen Sulfide

3. Properties of Myoglobin and Its Interaction with Hydrogen Sulfide

4. Interactions of Neuroglobin with Hydrogen Sulfide

5. Thiosulfate: From a Traditional Photographic Darkroom to Modern Medicine

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bilska, A.; Dudek, M.; Iciek, M.; Kwiecień, I.; Sokołowska-Jeżewicz, M.; Filipek, B.; Włodek, L. Biological actions of lipoic acid associated with sulfane sulfur metabolism. Pharmacol. Rep. 2008, 60, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iciek, M.; Bilska-Wilkosz, A.; Górny, M.; Sokołowska-Jeżewicz, M.; Kowalczyk-Pachel, D. The Effects of Different Garlic-Derived Allyl Sulfides on Anaerobic Sulfur Metabolism in the Mouse Kidney. Antioxidants 2016, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.L. Sulfane sulfur. Methods Enzymol. 1987, 143, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iciek, M.; Włodek, L. Biosynthesis and biological properties of compounds containing highly reactive, reduced sulfane sulfur. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 53, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bilska-Wilkosz, A.; Iciek, M.; Kowalczyk-Pachel, D.; Górny, M.; Sokołowska-Jeżewicz, M.; Włodek, L. Lipoic Acid as a Possible Pharmacological Source of Hydrogen Sulfide/Sulfane Sulfur. Molecules 2017, 22, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogasawara, Y.; Isoda, S.; Tanabe, S. Tissue and subcellular distribution of bound and acid-labile sulfur, and the enzymic capacity for sulfide production in the rat. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1994, 17, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikami, Y.; Shibuya, N.; Kimura, Y.; Nagahara, N.; Ogasawara, Y.; Kimura, H. Thioredoxin and dihydrolipoic acid are required for 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase to produce hydrogen sulfide. Biochem. J. 2011, 439, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, K.; Kimura, H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 1066–1071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bełtowski, J. Hydrogen sulfide in pharmacology and medicine—An update. Pharmacol. Rep. 2015, 67, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.U.I. Two’s company, three’s a crowd: Can H2S be the third endogenous gaseous transmitter? FASEB J. 2002, 16, 1792–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iciek, M.; Kowalczyk-Pachel, D.; Bilska-Wilkosz, A.; Kwiecień, I.; Górny, M.; Włodek, L. S-sulfhydration as a cellular redox regulation. Biosci. Rep. 2016, 36, e00304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, A.K.; Gadalla, M.M.; Sen, N.; Kim, S.; Mu, W.; Gazi, S.K.; Barrow, R.K.; Yang, G.; Wang, R.; Snyder, S.H. H2S signals through protein S-sulfhydration. Sci. Signal. 2009, 2, ra72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, B.D.; Snyder, S.H. H2S: A novel gasotransmitter that signals by sulfhydration. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libiad, M.; Yadav, P.K.; Vitvitsky, V.; Martinov, M.; Banerjee, R. Organization of the human mitochondrial hydrogen sulfide oxidation pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 30901–30910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmy, N.; Prip-Buus, C.; Vons, C.; Lenoir, V.; Abou-Hamdan, A.; Guedouari-Bounihi, H.; Lombès, A.; Bouillaud, F. Oxidation of hydrogen sulfide by human liver mitochondria. Nitric Oxide 2014, 41, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiranti, V.; Viscomi, C.; Hildebrandt, T.; di Meo, I.; Mineri, R.; Tiveron, C.; Levitt, M.D.; Prelle, A.; Fagiolari, G.; Rimoldi, M.; Zeviani, M. Loss of ETHE1, a mitochondrial dioxygenase, causes fatal sulfide toxicity in ethylmalonic encephalopathy. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackermann, M.; Kubitza, M.; Maier, K.; Brawanski, A.; Hauska, G.; Pina, A.L. The vertebrate homolog of sulfide-quinone reductase is expressed in mitochondria of neuronal tissues. Neuroscience 2011, 199, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koj, A.; Frendo, J. Oxidation of thiosulphate to sulphate in animal tissues. Folia Biol. 1967, 15, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Koj, A.; Frendo, J.; Janik, Z. Thiosulphate oxidation by rat liver mitochondria in the presence of glutathione. Biochem. J. 1967, 103, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skarżyński, B.; Szczepkowski, T.W.; Weber, M. Investigations on the oxidation of thiosulphate in the animal organism. Acta Biochim. Pol. 1960, 7, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Vitvitsky, V.; Yadav, P.K.; Kurthen, A.; Banerjee, R. Sulfide oxidation by a noncanonical pathway in red blood cells generates thiosulfate and polysulfides. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 8310–8320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umbreit, J. Methemoglobin—It’s not just blue: A concise review. Am. J. Hematol. 2007, 82, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, T.; Roy, A.; Chakraborti, A.S. Effect of non-enzymatic glycation on esterase activities of hemoglobin and myoglobin. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2007, 301, 251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Zapora, E.; Jarocka, I. Hemoglobin-source of reactive oxygen species. Postepy. Hig. Med. Dosw. 2013, 67, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Morales, E.; Pietri, R.; Ramos-Santana, B.; Vinogradov, S.N.; Lewis-Ballester, A.; López-Garriga, J. Structural determinants for the formation of sulfhemeprotein complexes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 400, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopalachar, A.S.; Bowie, V.L.; Bharadwaj, P. Phenazopyridine-induced sulfhemoglobinemia. Ann. Pharmacother. 2005, 39, 1128–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, A.; Goetz, D. A case of sulfhemoglobinemia in a child with chronic constipation. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2017, 21, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.P.; Gosselin, R.E. On the mechanism of sulfide inactivation by methemoglobin. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 1996, 8, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.R. The therapeutic potential of hydrogen sulfide: Separating hype from hope. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2011, 301, R297–R312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brittain, T.; Yosaatmadja, Y.; Henty, K. The interaction of human neuroglobin with hydrogen sulphide. IUBMB Life 2008, 60, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, D.W.; Wittenberg, J.B. Hemoglobins of the Lucina pectinata/bacteria symbiosis. I. Molecular properties, kinetics and equilibria of reactions with ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 16043–16053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vitvitsky, V.; Yadav, P.K.; An, S.; Seravalli, J.; Cho, U.S.; Banerjee, R. Structural and Mechanistic Insights into Hemoglobin-catalyzed Hydrogen Sulfide Oxidation and the Fate of Polysulfide Products. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 5584–5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodruff, W.W.; Whipple, G.H. Muscle hemoglobin in human autopsy material. Am. J. Pathol. 1928, 4, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kendrew, J.C.; Bodo, G.; Dintzis, H.M.; Parrish, R.G.; Wyckoff, H.; Phillips, D.C. A three-dimensional model of the myoglobin molecule obtained by x-ray analysis. Nature 1958, 181, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuckerkandl, E. The evolution of hemoglobin. Sci. Am. 1965, 212, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmquist, R.; Jukes, T.H.; Moise, H.; Goodman, M.; Moore, G.W. The evolution of the globin family genes: Concordance of stochastic and augmented maximum parsimony genetic distances for α hemoglobin, β hemoglobin and myoglobin phylogenies. J. Mol. Biol. 1976, 105, 39–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, D.W.; Wittenberg, J.B.; Lu, J.F.; Peisach, J. Hemoglobins of the Lucina pectinata/bacteria symbiosis. II. An electron paramagnetic resonance and optical spectral study of the ferric proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 16054–16059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bostelaar, T.; Vitvitsky, V.; Kumutima, J.; Lewis, B.E.; Yadav, P.K.; Brunold, T.C.; Filipovic, M.; Lehnert, N.; Stemmler, T.L.; Banerjee, R. Hydrogen sulfide oxidation by myoglobin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 8476–8488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burmester, T.; Weich, B.; Reinhardt, S.; Hankeln, T. A vertebrate globin expressed in the brain. Nature 2000, 407, 520–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuss, S.; Saaler-Reinhardt, S.; Weich, B.; Wystub, S.; Reuss, M.H.; Burmester, T.; Hankeln, T. Expression analysis of neuroglobin mRNA in rodent tissues. Neuroscience 2002, 115, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geuens, E.; Brouns, I.; Flamez, D.; Dewilde, S.; Timmermans, J.P.; Moens, L. A globin in the nucleus! J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 30417–30420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewilde, S.; Kiger, L.; Burmester, T.; Hankeln, T.; Baudin-Creuza, V.; Aerts, T.; Marden, M.C.; Caubergs, R.; Moens, L. Biochemical characterization and ligand binding properties of neuroglobin, a novel member of the globin family. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 38949–38955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascenzi, P.; di Masi, A.; Leboffe, L.; Fiocchetti, M.; Nuzzo, M.T.; Brunori, M.; Marino, M. Neuroglobin: From structure to function in health and disease. Mol. Aspects Med. 2016, 52, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruetz, M.; Kumutima, J.; Lewis, B.E.; Filipovic, M.R.; Lehnert, N.; Stemmler, T.L.; Banerjee, R. A Distal Ligand Mutes the Interaction of Hydrogen Sulfide with Human Neuroglobin. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 6512–6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linden, D.R.; Furne, J.; Stoltz, G.J.; Abdel-Rehim, M.S.; Levitt, M.D.; Szurszewski, J.H. Sulphide quinone reductase contributes to hydrogen sulphide metabolism in murine peripheral tissues but not in the CNS. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 165, 2178–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bijarnia, R.K.; Bachtler, M.; Chandak, P.G.; van Goor, H.; Pasch, A. Sodium thiosulfate ameliorates oxidative stress and preserves renal function in hyperoxaluric rats. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starostenko, E.V.; Dolzhanskiĭ, B.M.; Salpagarov, A.M.; Levchenko, T.N. The use of antioxidants in the complex therapy of patients with infiltrating pulmonary tuberculosis. Probl. Tuberk. 1991, 1, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.E.; McGinnis, G. Safety of intraventricular sodium nitroprusside and thiosulfate for the treatment of cerebral vasospasm in the intensive care unit setting. Stroke 2002, 33, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selye, H. The dermatologic implications of stress and calciphylaxis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1962, 39, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bild, D.E.; Detrano, R.; Peterson, D.O.; Guerci, A.; Liu, K.; Shahar, E.; Ouyang, P.; Jackson, S.; Saad, M.F. Ethnic differences in coronary calcification: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation 2005, 111, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasch, A.; Schaffner, T.; Huynh-Do, U.; Frey, B.M.; Frey, F.J.; Farese, S. Sodium thiosulfate prevents vascular calcifications in uremic rats. Kidney Int. 2008, 74, 1444–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asplin, J.R.; Donahue, S.E.; Lindeman, C.; Michalenka, A.; Strutz, K.L.; Bushinsky, D.A. Thiosulfate reduces calcium phosphate nephrolithiasis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noureddine, L.; Landis, M.; Patel, N.; Moe, S.M. Efficacy of sodium thiosulfate for the treatment for calciphylaxis. Clin. Nephrol. 2011, 75, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araya, C.E.; Fennell, R.S.; Neiberger, R.E.; Dharnidharka, V.R. Sodium thiosulfate treatment for calcific uremic arteriolopathy in children and young adults. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 1, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brucculeri, M.; Cheigh, J.; Bauer, G.; Serur, D. Long-term intravenous sodium thiosulfate in the treatment of a patient with calciphylaxis. Semin. Dial. 2004, 18, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicone, J.S.; Petronis, J.B.; Embert, C.D.; Spector, D.A. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2004, 4, 1104–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, G.; Shah, R.C.; Ross, E.A. Rapid resolution of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate and continuous venovenous haemofiltration using low calcium replacement fluid: Case report. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2005, 20, 1260–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.P.; Derendorf, H.; Ross, E.A. Simulation-based sodium thiosulfate dosing strategies for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 6, 1155–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strazzula, L.; Nigwekar, S.U.; Steele, D.; Tsiaras, W.; Sise, M.; Bis, S.; Smith, G.P.; Kroshinsky, D. Intralesional sodium thiosulfate for the treatment of calciphylaxis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013, 149, 946–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.X.; O’Neill, K.; Akl, N.K.; Moe, S.M. Adipocyte induced arterial calcification is prevented with sodium thiosulfate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 449, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, M.R.; Goldsmith, D.J. Sodium thiosulfate: New hope for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Semin. Dial. 2010, 23, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, U.; Vacek, T.P.; Hughes, W.M.; Kumar, M.; Moshal, K.S.; Tyagi, N.; Metreveli, N.; Hayden, M.R.; Tyagi, S.C. Cardioprotective role of sodium thiosulfate on chronic heart failure by modulating endogenous H2S generation. Pharmacology 2008, 82, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokuda, K.; Kida, K.; Marutani, E.; Crimi, E.; Bougaki, M.; Khatri, A.; Kimura, H.; Ichinose, F. Inhaled hydrogen sulfide prevents endotoxin-induced systemic inflammation and improves survival by altering sulfide metabolism in mice. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 17, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaguchi, M.; Marutani, E.; Shin, H.S.; Chen, W.; Hanaoka, K.; Xian, M.; Ichinose, F. Sodium thiosulfate attenuates acute lung injury in mice. Anesthesiology 2014, 121, 1248–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toohey, J.I. Sulfur signaling: Is the agent sulfide or sulfane? Anal. Biochem. 2011, 413, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishanina, T.V.; Libiad, M.; Banerjee, R. Biogenesis of reactive sulfur species for signaling by hydrogen sulfide oxidation pathways. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bilska-Wilkosz, A.; Iciek, M.; Górny, M.; Kowalczyk-Pachel, D. The Role of Hemoproteins: Hemoglobin, Myoglobin and Neuroglobin in Endogenous Thiosulfate Production Processes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18061315

Bilska-Wilkosz A, Iciek M, Górny M, Kowalczyk-Pachel D. The Role of Hemoproteins: Hemoglobin, Myoglobin and Neuroglobin in Endogenous Thiosulfate Production Processes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017; 18(6):1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18061315

Chicago/Turabian StyleBilska-Wilkosz, Anna, Małgorzata Iciek, Magdalena Górny, and Danuta Kowalczyk-Pachel. 2017. "The Role of Hemoproteins: Hemoglobin, Myoglobin and Neuroglobin in Endogenous Thiosulfate Production Processes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, no. 6: 1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18061315