Identification of Light-Independent Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Mutants Induced by Ethyl Methane Sulfonate in Turnip “Tsuda” (Brassica rapa)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

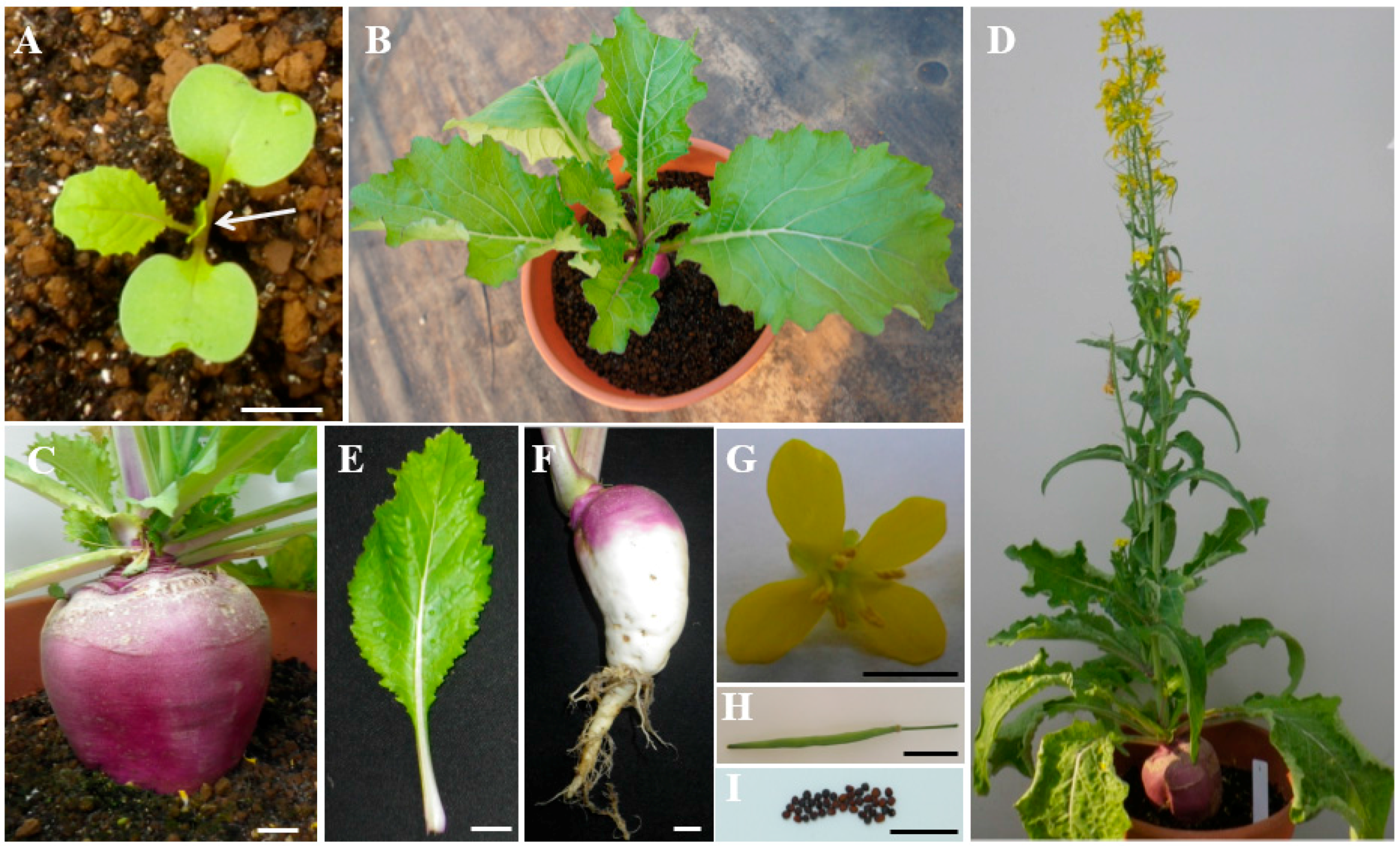

2.1. Characterization of Turnip “Tsuda” (Brassica rapa)

2.2. Optimization of Mutagen Dosage

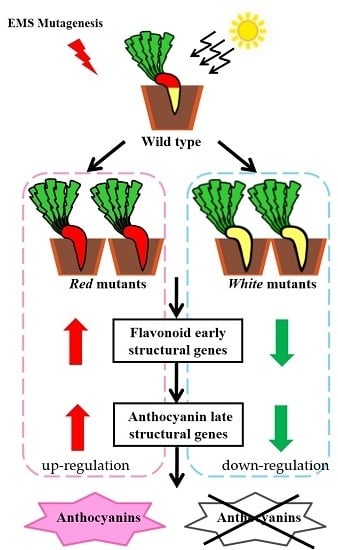

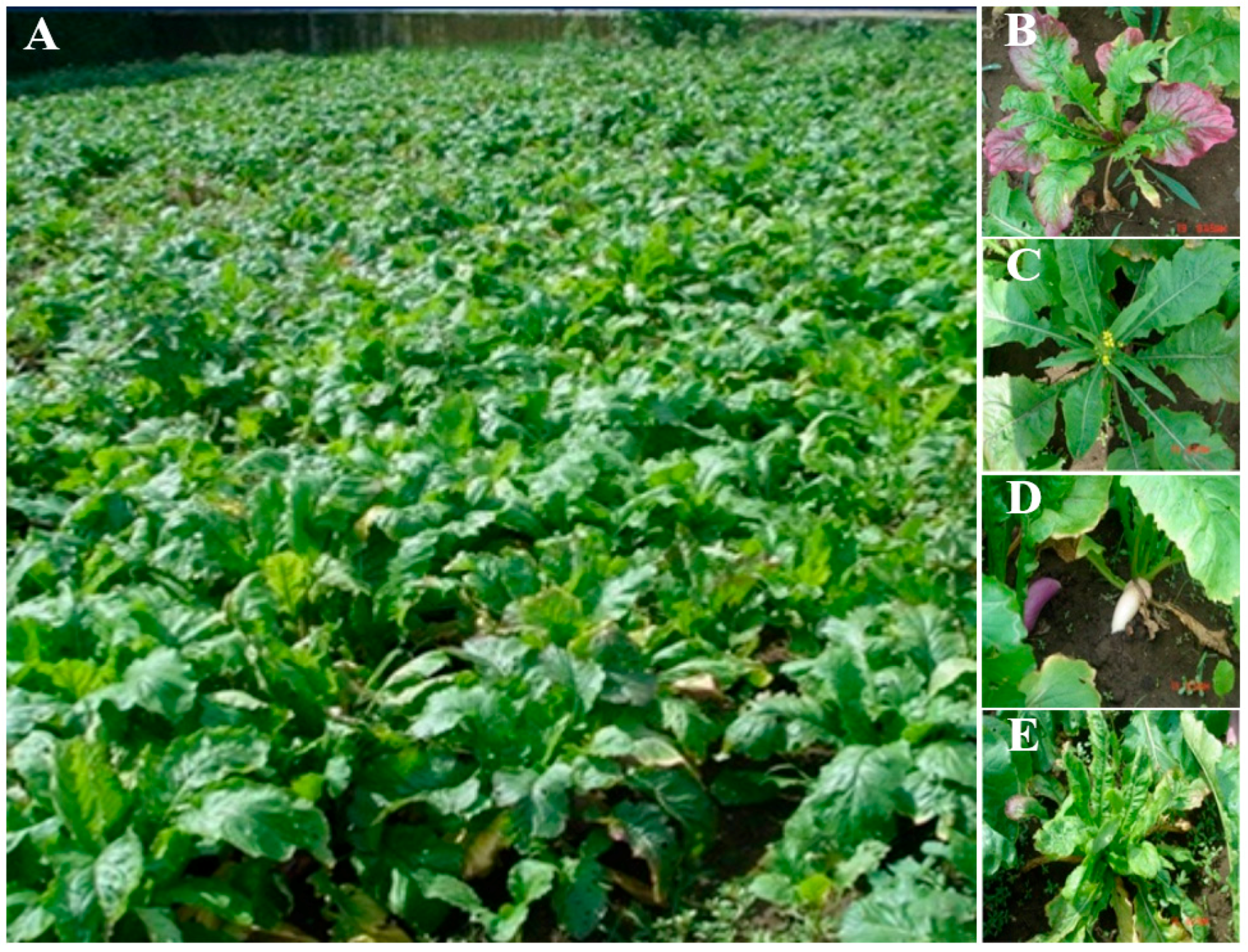

2.3. Screening Light-Independent Anthocyanin Mutants Induced by EMS

2.4. Genetic Analysis of the Anthocyanin Variations Mutants

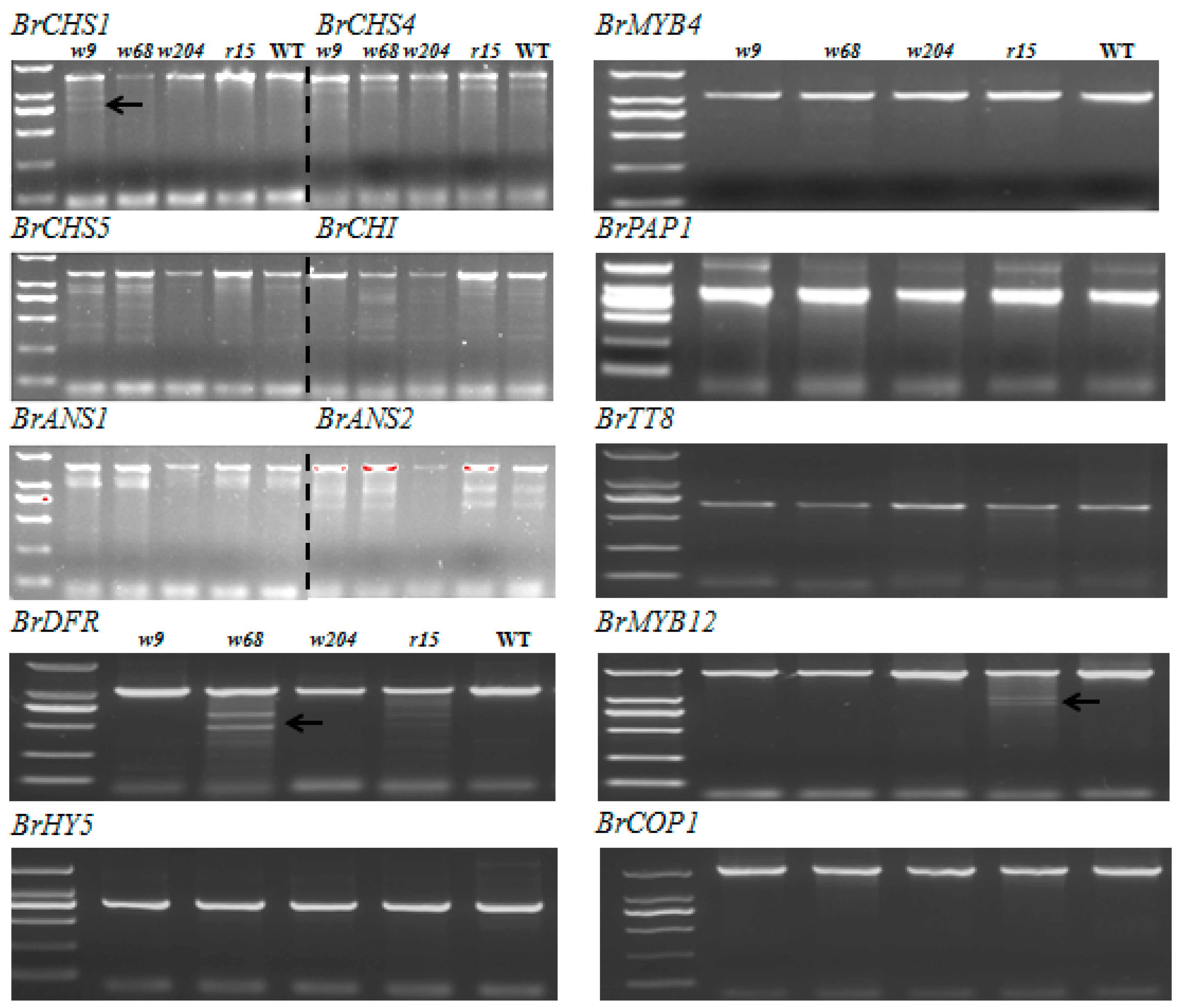

2.5. Scanning for Mutations by TILLING Analysis

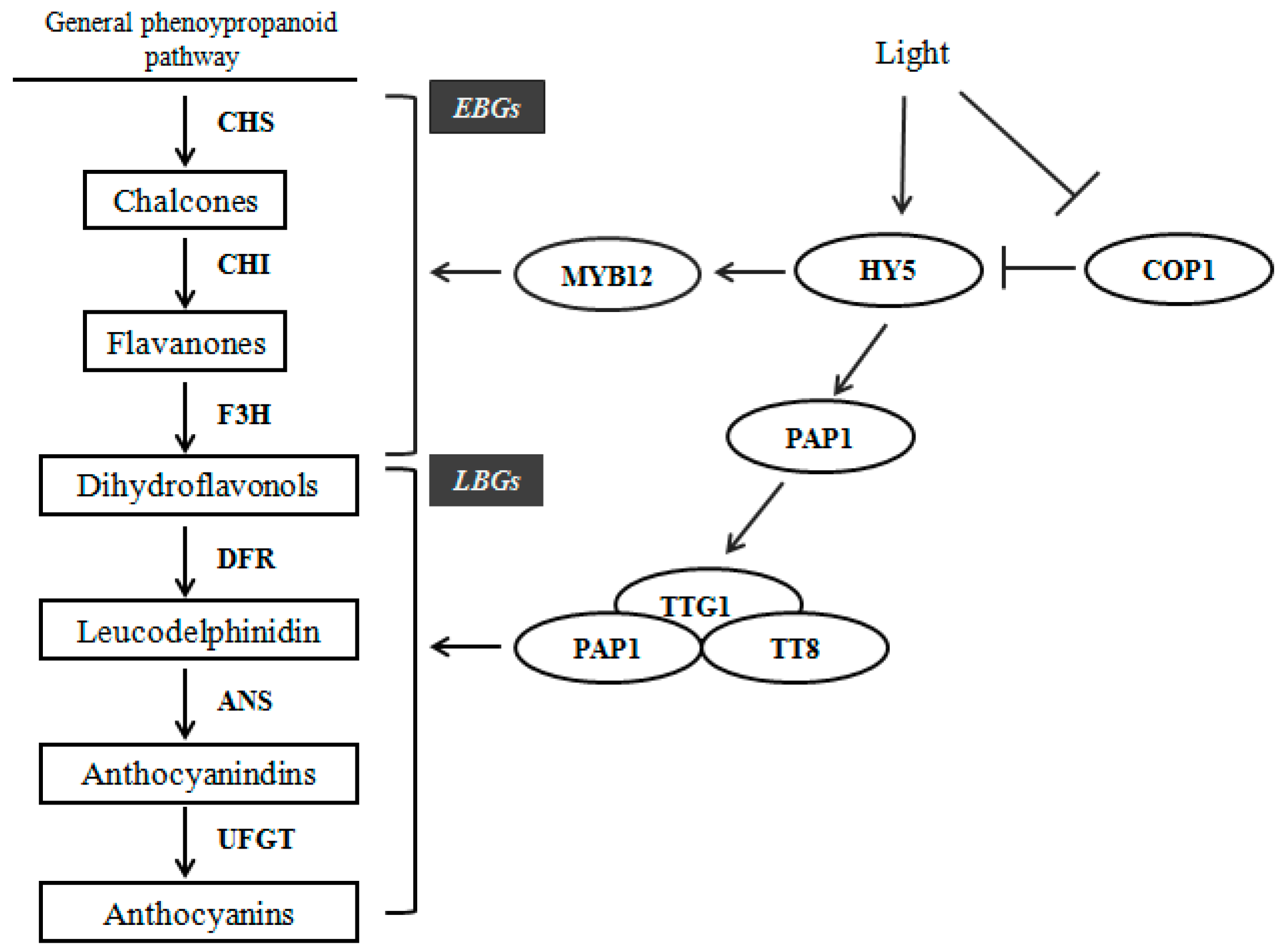

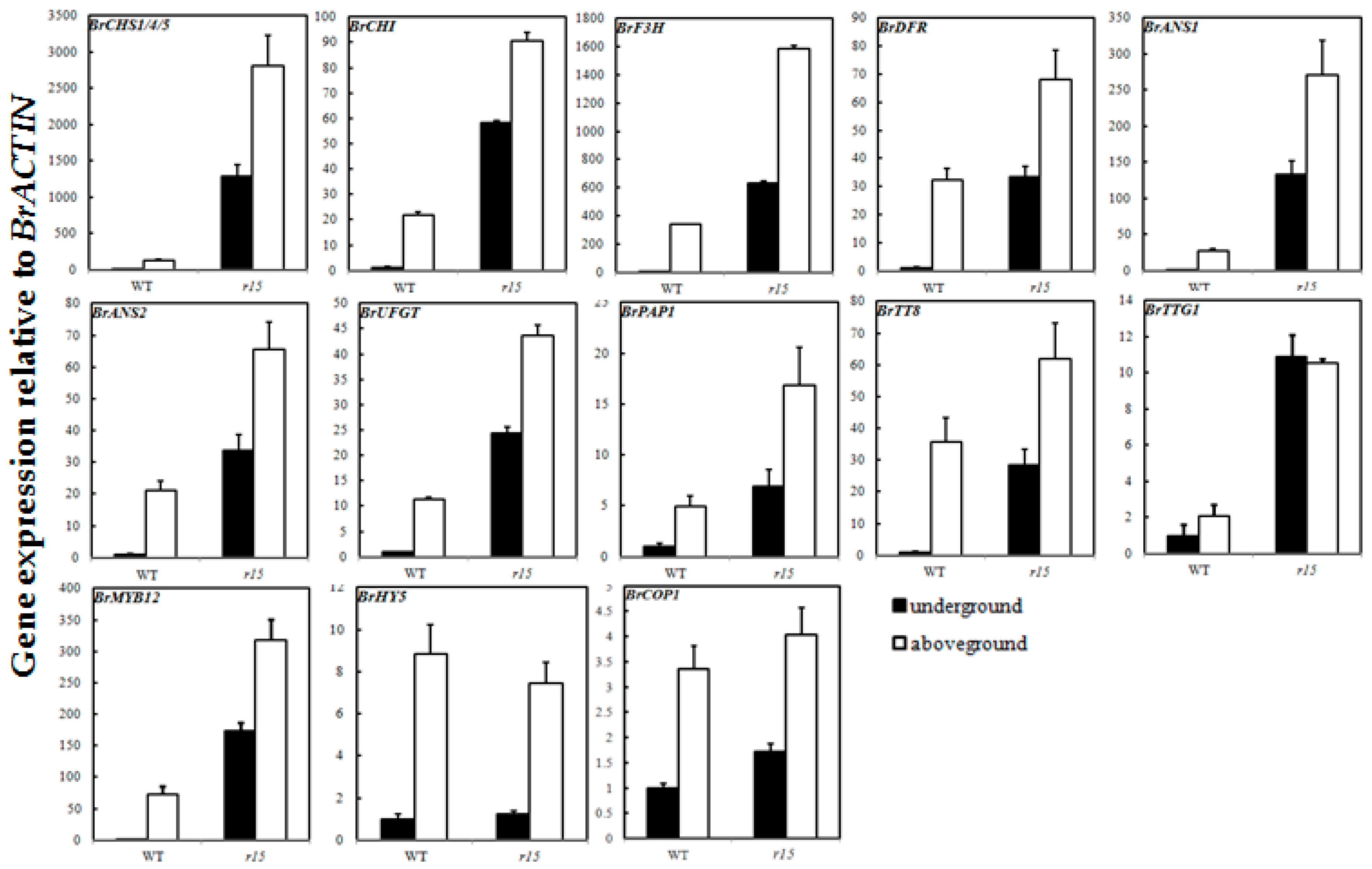

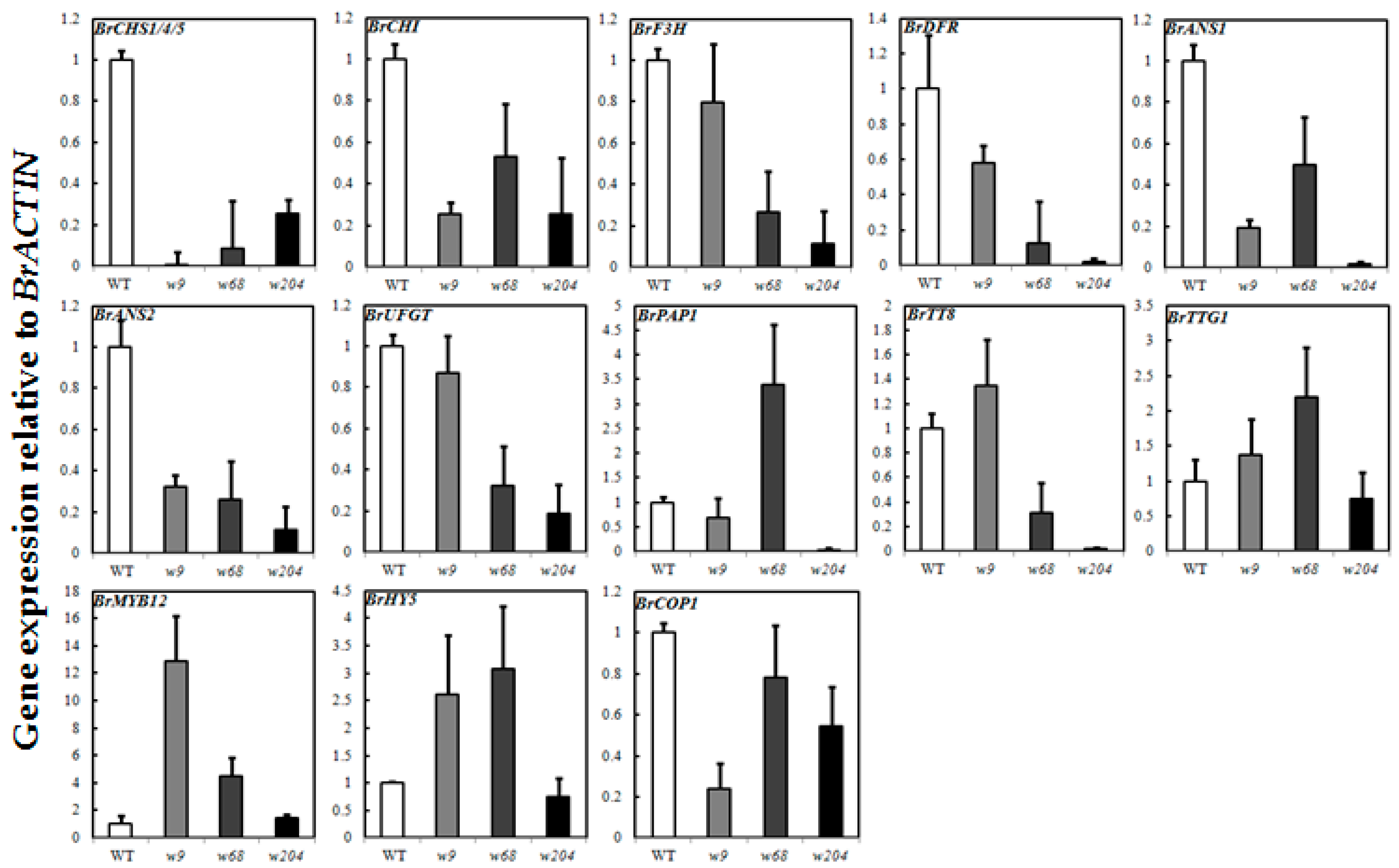

2.6. Expression Profiles of Anthocyanin Biosynthetic Genes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. EMS Mutagenesis and Plant Growth Conditions

4.3. M1 and M2 Population Generation

4.4. Anthocyanin Measurement

4.5. Genetic Analysis on Light-Independent Anthocyanin Mutants

4.6. TILLING Analysis

4.7. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EMS | Ethyl methane Sulfonate |

| CHS | Chalcone synthase |

| CHI | Chalcone isomerase |

| F3H | Flavanone 3-hydroxylase |

| DFR | Dihydroflavonol reductase |

| ANS | Anthocyanidin synthase |

| UFGT | UDP-flavonoid glucosyl transferase |

| PAP1 | Production of anthocyanin pigment 1 |

| TT8 | Transparent testa 8 |

| TTG1 | Transparent testa glabra 1 |

| HY5COP1 | Elongated hypocotyl 5Constitutively photomorphogenic 1 |

References

- Hu, D.G.; Sun, C.H.; Ma, Q.J.; You, C.X.; Cheng, L.; Hao, Y.J. MdMYB1 regulates anthocyanin and malate accumulation by directly facilitating their transport into vacuoles in apples. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 1315–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.B.; Li, S.; Zhang, R.F.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Y.C.; Zhao, Q.; Yao, Y.X.; You, C.X.; Zhang, X.S.; Hao, Y.J. The bHLH transcription factor MdbHLH3 promotes anthocyanin accumulation and fruit colouration in response to low temperature in apples. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 1884–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraco, M.; Spelt, C.; Bliek, M.; Verweij, W.; Hoshino, A.; Espen, L.; Prinsi, B.; Jaarsma, R.; Tarhan, E.; de Boer, A.H.; et al. Hyperacidification of vacuoles by the combined action of two different P-ATPases in the tonoplast determines flower color. Cell Rep. 2014, 6, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovinich, N.; Kayanja, G.; Chanoca, A.; Otegui, M.S.; Grotewold, E. Abiotic stresses induce different localizations of anthocyanins in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal Behav. 2015, 10, e1027850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.T.; Cheng, D.G.; Hsu, Y.T.; Kao, C.H. Abscisic acid-induced hydrogen peroxide is required for anthocyanin accumulation in leaves of rice seedlings. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 1280–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderauwera, S.; Zimmermann, P.; Rombauts, S.; Vandenabeele, S.; Langebartels, C.; Gruissem, W.; Inze, D.; van Breusegem, F. Genome-wide analysis of hydrogen peroxide-regulated gene expression in Arabidopsis reveals a high light-induced transcriptional cluster involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 806–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, B.; Yin, W.; Yu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, Z. Anthocyanin composition and expression analysis of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in kidney bean pod. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 97, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yao, G.; Yue, W.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J. Transcriptome profiling reveals differential gene expression in proanthocyanidin biosynthesis associated with red/green skin color mutant of pear (Pyrus communis L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, N.W.; Davies, K.M.; Lewis, D.H.; Zhang, H.; Montefiori, M.; Brendolise, C.; Boase, M.R.; Ngo, H.; Jameson, P.E.; Schwinn, K.E. A conserved network of transcriptional activators and repressors regulates anthocyanin pigmentation in eudicots. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 962–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, M.K.; Shirley, B.W. Analysis of flavanone 3-hydroxylase in Arabidopsis seedlings. Coordinate regulation with chalcone synthase and chalcone isomerase. Plant Physiol. 1996, 111, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirley, B.W.; Kubasek, W.L.; Storz, G.; Bruggemann, E.; Koornneef, M.; Ausubel, F.M.; Goodman, H.M. Analysis of Arabidopsis mutants deficient in flavonoid biosynthesis. Plant J. 1995, 8, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohge, T.; Nishiyama, Y.; Hirai, M.Y.; Yano, M.; Nakajima, J.; Awazuhara, M.; Inoue, E.; Takahashi, H.; Goodenowe, D.B.; Kitayama, M.; et al. Functional genomics by integrated analysis of metabolome and transcriptome of Arabidopsis plants over-expressing an MYB transcription factor. Plant J. 2005, 42, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, C.C.; Strahle, J.T.; Selinger, D.A.; Chandler, V.L. Mutations in the pale aleurone color1 regulatory gene of the Zea mays anthocyanin pathway have distinct phenotypes relative to the functionally similar transparent testa GLABRA1 gene in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Li, Y.; Kawabata, S. Chalcone synthase family genes have redundant roles in anthocyanin biosynthesis and in response to blue/UV-A light in turnip (Brassica rapa; Brassicaceae). Am. J. Bot. 2013, 100, 2458–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroni, K.; Tonelli, C. Recent advances on the regulation of anthocyanin synthesis in reproductive organs. Plant Sci. 2011, 181, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Grain, D.; Bobet, S.; Le Gourrierec, J.; Thevenin, J.; Kelemen, Z.; Lepiniec, L.; Dubos, C. Complexity and robustness of the flavonoid transcriptional regulatory network revealed by comprehensive analyses of MYB-bHLH-WDR complexes and their targets in Arabidopsis seed. New Phytol. 2014, 202, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, R.; Jahns, O.; Keck, M.; Tohge, T.; Niehaus, K.; Fernie, A.R.; Weisshaar, B. Analysis of production of flavonol glycosides-dependent flavonol glycoside accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana plants reveals MYB11-, MYB12- and MYB111-independent flavonol glycoside accumulation. New Phytol. 2010, 188, 985–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.; Zhao, M.; Leavitt, J.M.; Lloyd, A.M. Regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway by the TTG1/bHLH/MYB transcriptional complex in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant J. 2008, 53, 814–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Transcriptional control of flavonoid biosynthesis. Plant Signal. Behav. 2014, 9, e27522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.N.; Li, W.C.; Wang, H.C.; Shi, S.Y.; Shu, B.; Liu, L.Q.; Wei, Y.Z.; Xie, J.H. Transcriptome profiling of light-regulated anthocyanin biosynthesis in the pericarp of litchi. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Sun, Y.; Qian, M.; Yang, F.; Ni, J.; Tao, R.; Li, L.; Shu, Q.; Zhang, D.; Teng, Y. Transcriptome analysis of bagging-treated red chinese sand pear peels reveals light-responsive pathway functions in anthocyanin accumulation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Ren, L.; Lian, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H. Novel insight into the mechanism underlying light-controlled anthocyanin accumulation in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). Plant Sci. 2016, 249, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Cashmore, A.R. The blue-light receptor cryptochrome 1 shows functional dependence on phytochrome A or phytochrome B in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1997, 11, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.-S.; Liu, A. Light signaling induces anthocyanin biosynthesis via AN3 mediated COP1 expression. Plant Signal Behav. 2015, 10, e1001223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, H.K.; Bibikova, T.N.; Valentine, W.J.; Jenkins, G.I. Interactions within a network of phytochrome, cryptochrome and UV-B phototransduction pathways regulate chalcone synthase gene expression in Arabidopsis leaf tissue. Plant J. 2001, 25, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, M.; Sharma, P.; Khurana, J.P. Cryptochrome 1 from brassica napus is up-regulated by blue light and controls hypocotyl/stem growth and anthocyanin accumulation. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Lu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Xia, Y.; Xia, K.; Cui, J. UV-B-induced anthocyanin accumulation in hypocotyls of radish sprouts continues in the dark after irradiation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, Z.; Zhang, H. Repression of MYBL2 by both microRNA858a and HY5 leads to the activation of anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, R.; Favory, J.J.; Gruber, H.; Bartelniewoehner, L.; Bartels, S.; Binkert, M.; Funk, M.; Weisshaar, B.; Ulm, R. The Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor HY5 regulates expression of the PFG1/MYB12 gene in response to light and ultraviolet-B radiation. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.H.; Choi, M.; Kim, K.; Bang, G.; Cho, M.; Choi, S.B.; Choi, G.; Park, Y.I. HY5 regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis by inducing the transcriptional activation of the MYB75/PAP1 transcription factor in Arabidopsis. FEBS Lett. 2013, 587, 1543–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgakov, V.P.; Avramenko, T.V.; Tsitsiashvili, G.S. Critical analysis of protein signaling networks involved in the regulation of plant secondary metabolism: Focus on anthocyanins. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2016, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yan, H.; Homma, S.; Kawabata, S. Ultraviolet A-specific induction of anthocyanin biosynthesis in the swollen hypocotyls of turnip (Brassica rapa). J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 1771–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, B.; Sun, M.; Li, Y.; Kawabata, S. UV-a light induces anthocyanin biosynthesis in a manner distinct from synergistic blue + UV-B light and UV-A /blue light responses in different parts of the hypocotyls in turnip seedlings. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012, 53, 1470–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Huang, T.; Wang, F.; Yuan, F.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, S.; Wu, J.; Liu, K. A missense mutation in the vhynp motif of a della protein causes a semi-dwarf mutant phenotype in Brassica napus. TAG Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010, 121, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttner, B.; Abou-Elwafa, S.F.; Zhang, W.; Jung, C.; Muller, A.E. A survey of EMS-induced biennial β vulgaris mutants reveals a novel bolting locus which is unlinked to the bolting gene B. TAG Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010, 121, 1117–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Lin, W.; Li, W.; Gao, X.; Lv, L.; Ma, F.; Liu, Y. The analysis of physiological variations in M2 generation of Solanum melongena L. Mutagenized by ethyl methane sulfonate. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, A.K.; Mohan, A.; Sidhu, G.; Maqbool, R.; Gill, K.S. An ethylmethane sulfonate mutant resource in pre-green revolution hexaploid wheat. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisha, M.H.; Shah, S.N.; Gong, Z.H.; Jing, H.; Li, C.; Zhang, H.X. Ethyl methane sulfonate induced mutations in M2 generation and physiological variations in M1 generation of peppers (Capsicum annuum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisha, M.H.; Liang, B.K.; Muhammad Shah, S.N.; Gong, Z.H.; Li, D.W. Kill curve analysis and response of first generation Capsicum annuum L. B12 cultivar to ethyl methane sulfonate. Genet. Mol. Res. 2014, 13, 10049–10061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Sun, M.; Wang, J.; Kawabata, S.; Li, Y. BrMYB4, a suppressor of genes for phenylpropanoid and anthocyanin biosynthesis, is down-regulated by UV-B but not by pigment-inducing sunlight in turnip cv. Tsuda. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 2092–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, B.; Kawabata, S.; Li, Y. Comparative transcriptome analysis revealed distinct gene set expression associated with anthocyanin biosynthesis in response to short-wavelength light in turnip. Acta Physiol. Plant 2016, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, P.; Baker, D.; Girin, T.; Perez, A.; Amoah, S.; King, G.J.; Ostergaard, L. A rich tilling resource for studying gene function in Brassica rapa. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, L.; Yuan, G.; Heng, S.; Yi, B.; Ma, C.; Shen, J.; Tu, J.; Fu, T.; Wen, J. Fine mapping and candidate gene analysis of an anthocyanin-rich gene, Bnaa.PL1, conferring purple leaves in Brassica napus L. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2016, 291, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, Y.; Tian, F.; King, G.J.; Zhang, C.; Long, Y.; Shi, L.; Meng, J. A functional genomics resource for brassica napus: Development of an ems mutagenized population and discovery of FAE1 point mutations by tilling. New Phytol. 2008, 180, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, S.D.; Weselake, R.J.; Rahman, H. Development and characterization of low α-linolenic acid Brassica oleracea lines bearing a novel mutation in a ‘class a’ fatty acid desaturase 3 gene. BMC Genet. 2014, 15, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, A.; Schrader, A.; Kokkelink, L.; Falke, C.; Welter, B.; Iniesto, E.; Rubio, V.; Uhrig, J.F.; Hulskamp, M.; Hoecker, U. Light and the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1/SPA control the protein stability of the MYB transcription factors PAP1 and PAP2 involved in anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2013, 74, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Cominelli, E.; Bailey, P.; Parr, A.; Mehrtens, F.; Jones, J.; Tonelli, C.; Weisshaar, B.; Martin, C. Transcriptional repression by AtMYB4 controls production of UV-protecting sunscreens in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 6150–6161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.Y.; Felippes, F.F.; Liu, C.J.; Weigel, D.; Wang, J.W. Negative regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis by a miR156-targeted SPL transcription factor. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1512–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Fan, P.; Li, Y.; Yan, H.; Xu, Q. Exploring mirnas involved in blue/UV-A light response in Brassica rapa reveals special regulatory mode during seedling development. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.V.; Patel, V.; Nordström, K.J.V.; Klasen, J.R.; Salomé, P.A.; Weigel, D.; Schneeberger, K. User guide for mapping-by-sequencing in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, R61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekih, R.; Takagi, H.; Tamiru, M.; Abe, A.; Natsume, S.; Yaegashi, H.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, S.; Kanzaki, H.; Matsumura, H.; et al. Mutmap+: Genetic mapping and mutant identification without crossing in rice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, A.; Kosugi, S.; Yoshida, K.; Natsume, S.; Takagi, H.; Kanzaki, H.; Matsumura, H.; Yoshida, K.; Mitsuoka, C.; Tamiru, M. Genome sequencing reveals agronomically important loci in rice using mutmap. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, V.; Bres, C.; Just, D.; Fernandez, L.; Tai, F.W.J.; Mauxion, J.P.; Paslier, M.C.L.; Bérard, A.; Brunel, D.; Aoki, K. Rapid identification of causal mutations in tomato ems populations via mapping-by-sequencing. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 2401–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EMS Treatment (W/V) | 0.00% | 0.25% | 0.50% | 1.00% | 2.00% | 5.00% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. of seeds | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| No. of germinated seeds | 191 | 148 | 97 | 29 | 0 | 0 |

| Germination rate (GR) | 95.5% | 74% | 48.5% | 14.5% | 0% | 0% |

| Relative germination rate | 100% | 77.5% | 51% | 15.5% | 0% | 0% |

| Content | r15 | w9 | w68 | w204 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of WT plants | 141 | 152 | 114 | 133 |

| No. of mutant plants | 55 | 38 | 45 | 35 |

| Total plants | 196 | 190 | 159 | 168 |

| p value (χ2 = 3:1) | 0.322 | 0.111 | 0.336 | 0.212 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, J.-F.; Chen, Y.-Z.; Kawabata, S.; Li, Y.-H.; Wang, Y. Identification of Light-Independent Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Mutants Induced by Ethyl Methane Sulfonate in Turnip “Tsuda” (Brassica rapa). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18071288

Yang J-F, Chen Y-Z, Kawabata S, Li Y-H, Wang Y. Identification of Light-Independent Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Mutants Induced by Ethyl Methane Sulfonate in Turnip “Tsuda” (Brassica rapa). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017; 18(7):1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18071288

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Jian-Fei, Yun-Zhu Chen, Saneyuki Kawabata, Yu-Hua Li, and Yu Wang. 2017. "Identification of Light-Independent Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Mutants Induced by Ethyl Methane Sulfonate in Turnip “Tsuda” (Brassica rapa)" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, no. 7: 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18071288