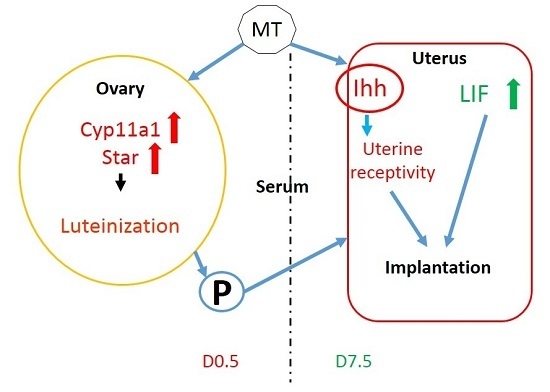

Effects of Melatonin on Early Pregnancy in Mouse: Involving the Regulation of StAR, Cyp11a1, and Ihh Expression

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

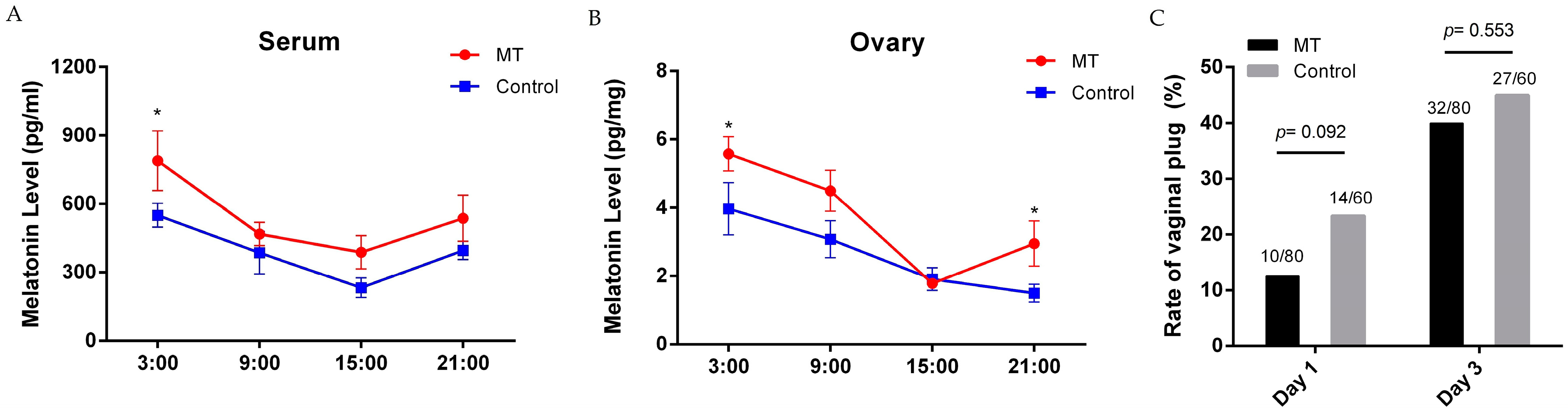

2.1. Effects of Melatonin on Mice Estrus

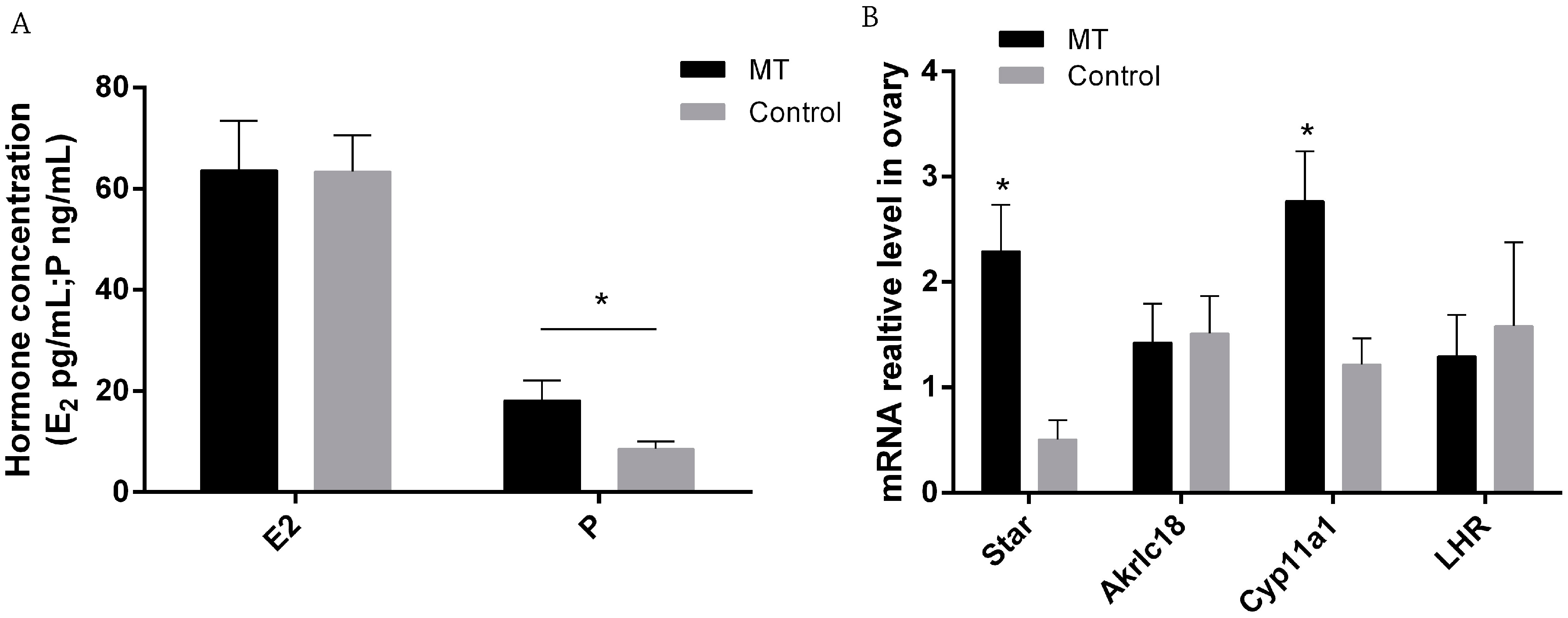

2.2. Effects of Melatonin on E2 and P Secretion and Gene Expression in Ovaries on 0.5 Day Gestation

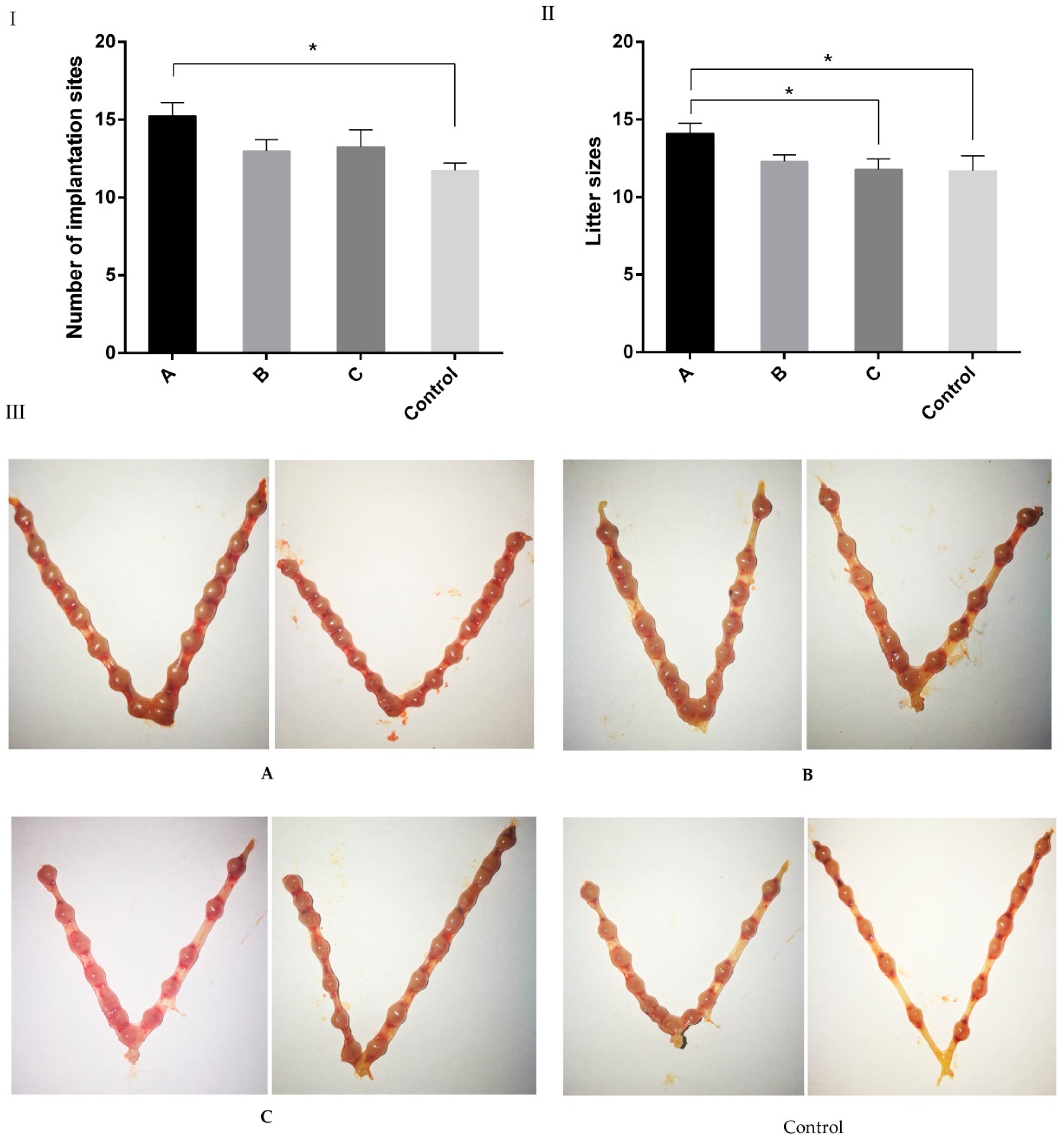

2.3. Effects of Melatonin on Implantation and Litter Size on 7.5 Day of Gestation Mice

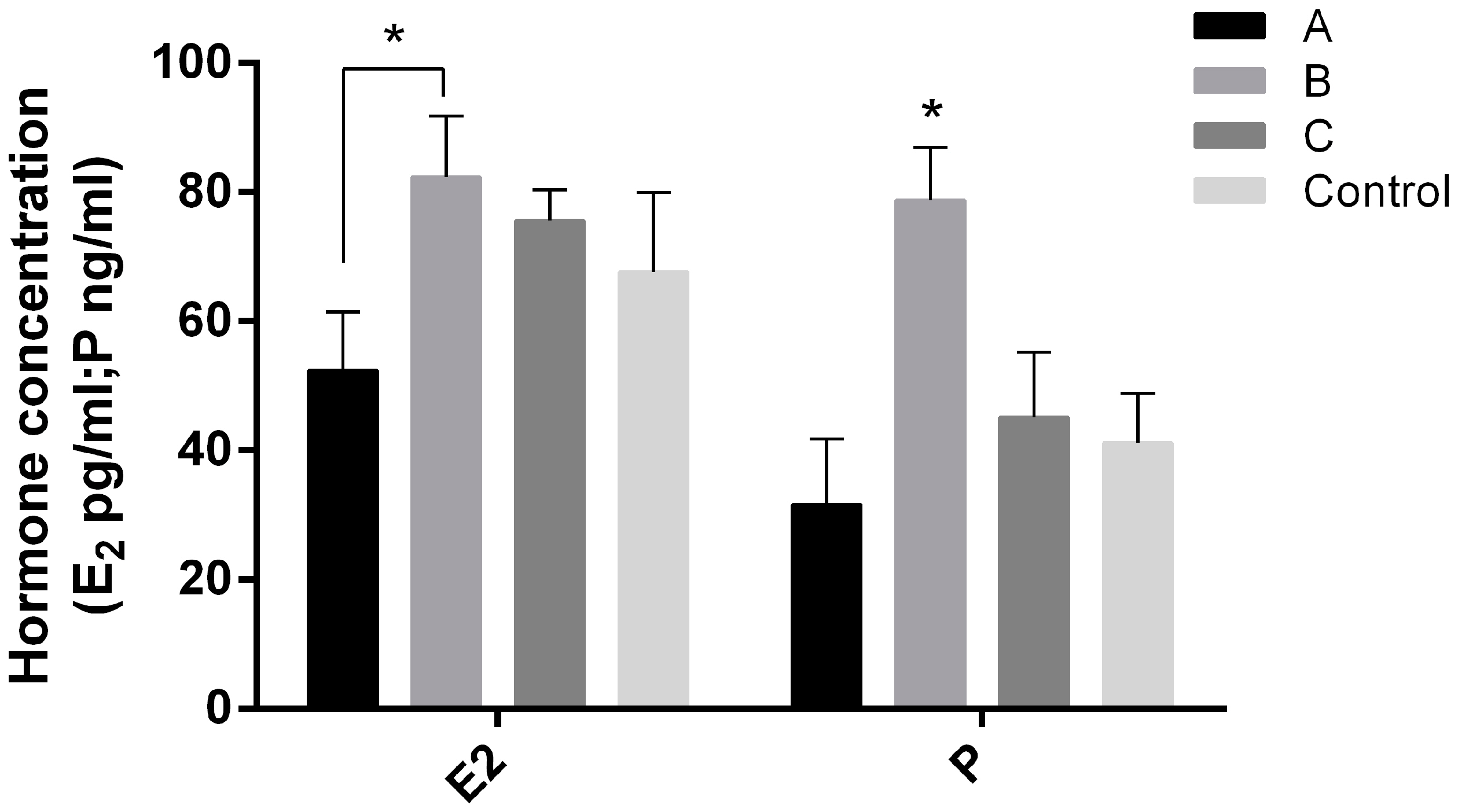

2.4. Effects of Melatonin on Serum E2 and P Levels on Day 7.5 of Early Pregnant Mice

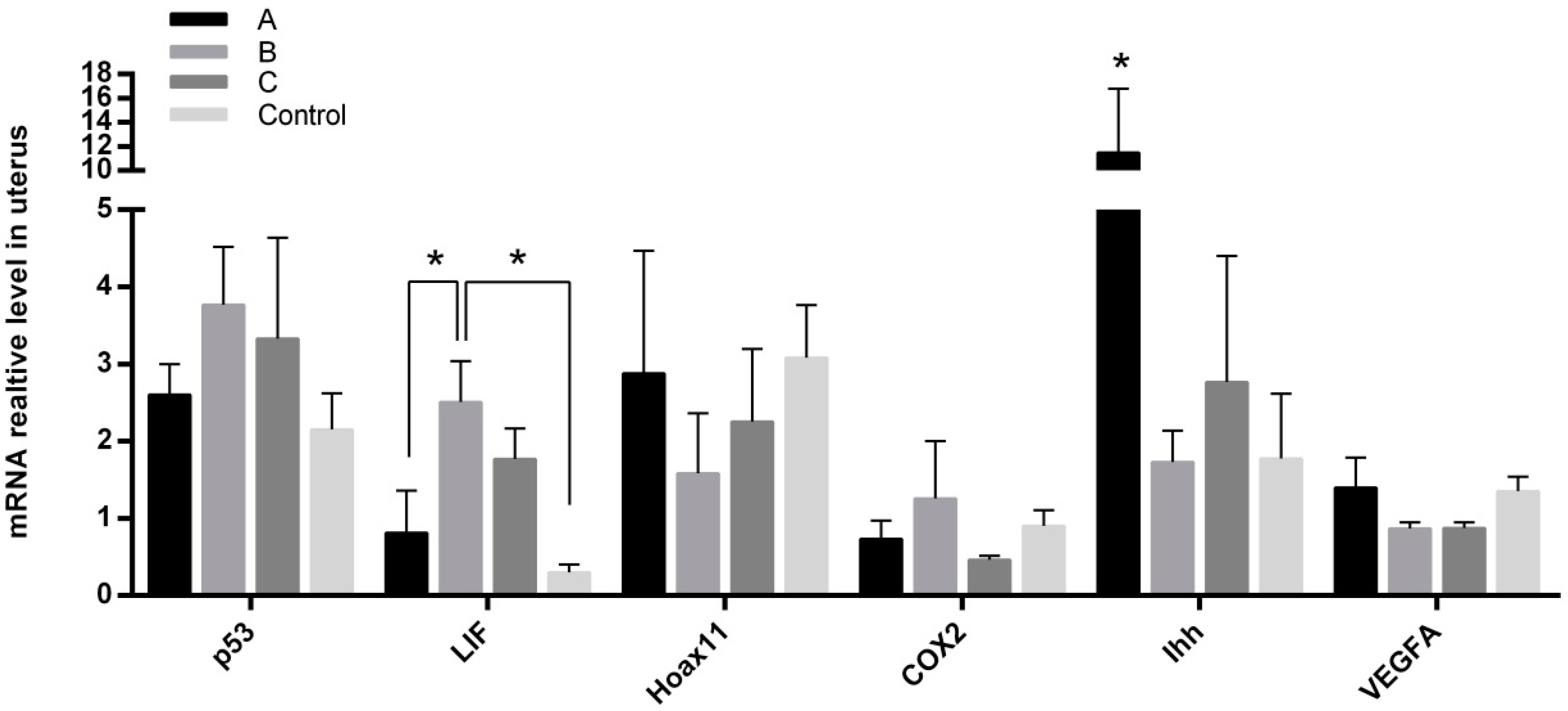

2.5. Effects of Melatonin on Gene Expressions in Mice Endometrium

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Experiment Designs

4.3. The Assays of Melatonin, Estradiol-17β, and Progesterone

4.4. Implantation Sites Counting

4.5. Gene Expression Assay by Real-Time Q-PCR

4.6. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MT | Melatonin |

| AANAT | Aralkylamine N-acetyltransferase |

| ASMT | Acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase |

| HPG axis | Hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis |

| Km | Michaelis constant |

| Q-PCR | Quantitative PCR |

| E2 | Estradiol-17β |

| P | Progesterone |

| RIA | Radioimmunoassays |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| Akr1c18 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C18 |

| p53 | Transformation related protein 53 |

| StAR | Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein |

| Cyp11a1 | Cytochrome P450 family 11 subfamily A member 1 |

| LHR | Luteinizing hormone receptor |

| VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| Hoxa11 | Homeobox A11 |

| Ihh | Indian hedgehog |

| COX2 | CYCLOOXYGENASE-2 |

| LIF | Leukaemia inhibitory factor |

References

- Dey, S.K.; Lim, H.; Das, S.K.; Reese, J.; Paria, B.C.; Daikoku, T.; Wang, H. Molecular cues to implantation. Endocr. Rev. 2004, 25, 341–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Dey, S.K. Roadmap to embryo implantation: Clues from mouse models. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006, 7, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, A.B.; Case, J.D.; Takahashi, Y. Isolation of melatonin, the pineal gland factor that lightens melanocyte. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 10, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paria, B.C.; Reese, J.; Das, S.K.; Dey, S.K. Deciphering the cross-talk of implantation: Advances and challenges. Science 2002, 296, 2185–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, D.X.; Manchester, L.C.; Qin, L.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin: A mitochondrial targeting molecule involving mitochondrial protection and dynamics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, R.J.; Tan, D.X.; Galano, A. Melatonin: Exceeding expectations. Physiology 2014, 29, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Li, N.; Bo, L.; Xu, Z. Melatonin and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 2017–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renuka, K.; Joshi, B.N. Melatonin-induced changes in ovarian function in the freshwater fish Channa punctatus (Bloch) held in long days and continuous light. Gen. Comp. Endocr. 2010, 165, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarter, S.J.; Boswell, C.L.; St. Louis, E.K.; Dueffert, L.G.; Slocumb, N.; Boeve, B.F.; Silber, M.H.; Olson, E.J; Tippmann-Peikert, M. Treatment outcomes in REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2013, 14, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, P.; Bolborea, M. Molecular pathways involved in seasonal body weight and reproductive responses governed by melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 2012, 52, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Wang, F.; He, C.; Zhang, L.; Tan, D.; Reiter, R.J.; Xu, J.; Ji, P.; Liu, G. Beneficial effects of melatonin on bovine oocyte maturation: A mechanistic approach. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeNicolo, G.; Morris, S.T.; Kenyon, P.R.; Morel, P.C.; Parkinson, T.J. Melatonin-improved reproductive performance in sheep bred out of season. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2008, 109, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pévet, P.; Haldar-Misra, C. Effect of orally administered melatonin on reproductive function of the golden hamster. Experientia 1982, 38, 1493–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, L.H.; Swanson, W.F.; Wildt, D.E. Influence of oral melatonin on natural and gonadotropin-induced ovarian function in the domestic cat. Theriogenology 2004, 61, 1061–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dair, E.L.; Simoes, R.S.; Simões, M.J.; Romeu, L.R.; Oliveira-Filho, R.M.; Haidar, M.A.; Baracat, E.C.; Soares, J.M., Jr. Effects of melatonin on the endometrial morphology and embryo implantation in rats. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 89, 1299–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galano, A.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. On the free radical scavenging activities of melatonin’s metabolites, AFMK and AMK. J. Pineal Res. 2013, 54, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galano, A.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin as a natural ally against oxidative stress: A physicochemical examination. J. Pineal Res. 2011, 51, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manchester, L.C.; Coto-Montes, A.; Boga, J.A.; Andersen, L.P.; Zhou, Z.; Galano, A.; Vriend, J.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin: An ancient molecule that makes oxygen metabolically tolerable. J. Pineal Res. 2015, 59, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, K.; Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, L.; Ding, Y.; Zhu, L.; He, J.; Zhou, M. Melatonin stimulates antioxidant enzymes and reduces oxidative stress in experimental traumatic brain injury: The Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway as a potential mechanism. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 73, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, R.J.; Mayo, J.C.; Tan, D.X.; Sainz, R.M.; Alatorre-Jimenez, M.; Qin, L. Melatonin as an antioxidant: Under promises but over delivers. J. Pineal Res. 2016, 61, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yi, W.; Li, Y.; Fan, C.; Xin, Z.; Jiang, S.; Di, S.; Qu, Y.; Reiter, R.J.; et al. A review of melatonin as a suitable antioxidant against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and clinical heart diseases. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, H.; Takasaki, A.; Miwa, I.; Taniguchi, K.; Maekawa, R.; Asada, H.; Taketani, T.; Matsuoka, A.; Yamagata, Y.; Shimamura, K.; et al. Oxidative stress impairs oocyte quality and melatonin protects oocytes from radical damage and improves fertilization rate. J. Pineal Res. 2008, 44, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, M.; Tamura, H.; Taketani, T.; Okada, M.; Lee, L.; Tamura, I.; Maekawa, R.; Asada, H.; Yamagata, Y.; Sugino, N. Melatonin protects the integrity of granulosa cells by reducing oxidative stress in nuclei, mitochondria, and plasma membranes in mice. J. Reprod. Dev. 2015, 61, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, J.J.; López-Pingarrón, L.; Almeida-Souza, P.; Tres, A.; Escudero, P.; García-Gil, F.A.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J.; Ramírez, J.M.; Bernal-Pérez, M. Protective effects of melatonin in reducing oxidative stress and in preserving the fluidity of biological membranes: A review. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 56, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, R.J.; Tan, D.X. Melatonin: A novel protective agent against oxidative injury of the ischemic/reperfused heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003, 58, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.M.; Zhang, Y. Melatonin: A well-documented antioxidant with conditional pro-oxidant actions. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Mouatassim, S.; Guérin, P.; Ménézo, Y. Expression of genes encoding antioxidant enzymes in human and mouse oocytes during the final stages of maturation. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 5, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, H.; Kawamoto, M.; Sato, S.; Tamura, I.; Maekawa, R.; Taketani, T.; Aasada, H.; Takaki, E.; Nakai, A.; Reiter, R.J.; et al. Long-term melatonin treatment delays ovarian aging. J. Pineal Res. 2017, 62, e12381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Hasan, K.N.; Maitra, S.K. Melatonin actions on ovaprim (synthetic GnRH and domperidone)-induced oocyte maturation in carp. Reproduction 2016, 151, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, K.; Xu, Z.; Song, Y.; Song, Y.; Liu, G. Melatonin-related genes expressed in the mouse uterus during early gestation promote embryo implantation. J. Pineal Res. 2015, 58, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaki, Y.; Wurtman, R.; Alonso, R.; Lynch, H.J. Melatonin secretion decreases during the proestrous stage of the rat estrous cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 75, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Korkmaz, A.; Manchester, L.C.; Tan, D.X.; Sugino, N.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin and the ovary: Physiological and pathophysiological implications. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 92, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, H.; Takasaki, A.; Taketani, T.; Tanabe, M.; Lee, L.; Tamura, I.; Maekawa, R.; Aasada, H.; Yamagata, Y.; Sugino, N. Melatonin and female reproduction. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2014, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, R.J.; Tamura, H.; Tan, D.X.; Xu, X. Melatonin and the circadian system: Contributions to successful female reproduction. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 102, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Miao, Y.; Zhou, C.; Cui, Z.; Xiong, B. Melatonin improves the fertilization ability of post-ovulatory aged mouse oocytes by stabilizing ovastacin and Juno to promote sperm binding and fusion. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradip, M.; Kazi, N.H.; Palash, K.P.; Saumen, K.M. Influences of exogenous melatonin on the oocyte growth and oxidative status of ovary during different reproductive phases of an annual cycle in carp Catla catla. Theriogenology 2017, 87, 349–359. [Google Scholar]

- He, C.; Ma, T.; Shi, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhu, K.; Li, Y.; Yang, M.; Song, Y.; Liu, G. Melatonin and its receptor MT1 are involved in the downstream reaction to luteinizing hormone and participate in the regulation of luteinization in different species. J. Pineal Res. 2016, 61, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, T.A.; Sharma, R.K.; Phulia, S.K.; Balhara, A.K.; Ghuman, S.S.; Singh, I. Manipulation of reproductive performance of lactating buffaloes using melatonin and controlled internal drug release device treatment during out-of-breeding season under tropical conditions. Theriogenology 2016, 86, 1048–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, L.P.; Werner, M.U.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; Harpsøe, N.G.; Fuglsang, H.; Rosenberg, J.; Gögenur, I. Pharmacokinetics of oral and intravenous melatonin in healthy volunteers. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016, 19, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenezkrassel, F.; Folger, J.K.; Ireland, J.L.; Smith, G.W.; Hou, X.; Davis, J.S. Evidence that high variation in ovarian reserves of healthy young adults has a negative impact on the corpus luteum and endometrium during estrous cycles in cattle. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 80, 1272–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arakane, F.; Kallen, C.B.; Watari, H.; Foster, J.A.; Sepuri, N.B.; Pain, D.; Stayrook, S.E.; Lewis, M.; Gerton, G.L.; Strauss, J.F. The mechanism of action of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (stAR). stAR acts on the outside of mitochondria to stimulate steroidogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 16339–16345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, L.M. Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), a novel mitochondrial cholesterol transporter. BBA Mol. Cell. Res. 2007, 1771, 663–676. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, S.W.; Clark, J.; Myers, P.; Korach, K.S. Disruption of estrogen signaling does not prevent progesterone action in the estrogen receptor α knockout mouse uterus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 3646–3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paria, B.C.; Tan, J.; Lubahn, D.B.; Dey, S.K.; Das, S.K. Uterine decidual response occurs in estrogen receptor-α-deficient mice. Endocrinology 1999, 140, 2704–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuffa, L.G.; Seiva, F.R.; Fávaro, W.J.; Amorim, J.P.; Teixeira, G.R.; Mendes, L.O.; Fioruci-Fontanelli, B.A.; Pinheiro, P.F.; Martinez, M.; Martinez, F.E. Melatonin and ethanol intake exert opposite effects on circulating estradiol and progesterone and differentially regulate sex steroid receptors in the ovaries, oviducts, and uteri of adult rats. Reprod. Toxicol. 2013, 39, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, T.H.; Lee, F.K.; Lin, T.K.; Horng, S.G.; Chen, S.C.; Chen, Y.H.; Wang, P.C. An increased serum progesterone-to-estradiol ratio on the day of human chorionic gonadotropin administration does not have a negative impact on clinical pregnancy rate in women with normal ovarian reserve treated with a long gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist protocol. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 92, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.; Chien, L.; Tzeng, C. A single day16 serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level combined with estradiol/progesterone (E2/P) ratio may predict pregnancy outcomes following intrauterine insemination. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 92, 508–514. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.G.; Song, H.; Das, S.K.; Paria, B.C.; Dey, S.K. Estrogen is a critical determinant that specifies the duration of the window of uterine receptivity for implantation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 2963–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, D.; Chen, W.; Fu, L.; Liu, L.; Xie, F.; Kang, T.; Huang, W.; et al. Simultaneous modulation of COX-2, p300, Akt, and Apaf-1 signaling by melatonin to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in breast cancer cells. J. Pineal Res. 2012, 53, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeu, L.R.; da Motta, E.L.; Maganhin, C.C.; Oshima, C.T.; Fonseca, M.C.; Barrueco, K.F.; Simões, R.S.; Pellegrino, R.; Baracat, E.C.; Soares-Junio, J.M. Effects of melatonin on histomorphology and on the expression of steroid receptors, VEGF, and PCNA in ovaries of pinealectomized female rats. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 1379–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Deng, W.; Li, M.; Zhao, Z.A.; Wang, T.S.; Feng, X.H.; Cao, Y.J.; Duan, E.K.; Yang, Z.M. Egr1 protein acts downstream of estrogen-leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF)-STAT3 pathway and plays a role during implantation through targeting Wnt4. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 23534–23545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.S.; Gao, F.; Qi, Q.; Qin, F.N.; Zuo, R.J.; Li, Z.L.; Liu, J.L.; Yang, Z.M. Dysregulated LIF-STAT3 pathway is responsible for impaired embryo implantation in a Streptozotocin-induced diabetic mouse model. Biol. Open 2015, 4, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, H.; Zhao, X.; Das, S.K.; Hogan, B.L.; Dey, S.K. Indian hedgehog as a progesterone-responsive factor mediating epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in the mouse uterus. Dev. Biol. 2002, 245, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filant, J.; Spencer, T.E. Endometrial glands are essential for blastocyst implantation and decidualization in the mouse uterus. Biol. Reprod. 2013, 88, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genes | Primer Sequence (5′–3′) | Tm (°C) | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | Forward: CCTGGAGAAACCTGCCAAGTAT | 60 | XM_017321385 |

| Reverse: GGAAGAGTGGGAGTTGCTGTTG | |||

| Akr1c18 | Forward: TTGGTCAACTTCCCATCGTC | 59 | NM_134066 |

| Reverse: GCCCTGCATCCTTACACTTC | |||

| P53 | Forward: TGAGGTTCGTGTTTGTGCCTGC | 60 | NM_001127233 |

| Reverse: CCATCAAGTGGTTTTTTCTTTTGC | |||

| StAR | Forward: CCTTGGGCATACTCAACAACC | 60 | NM_011485 |

| Reverse: CCACATCTGGCACCATCTTACTT | |||

| Cyp11a1 | Forward: GGGCAGTTTGGAGTCAGTTTAC | 60 | NM_001346787.1 |

| Reverse: TTTAGGACGATTCGGTCTTTCTT | |||

| LHR | Forward: CTGAGGAGATTTGGTTGCTGTA | 60 | NM_013582 |

| Reverse: ATTTGGGTGGACTTTTTTGGGG | |||

| MT2 | Forward: GGTGGCTCCCATGCTATCTA | 59 | NM_008630 |

| Reverse: AAACAAATTACCTGCGTTCCG | |||

| VEGFA | Forward: GAGAAGACAGGGTGGTGGAAG | 59 | NM_001025250 |

| Reverse: GAAGGGAAGATGAGGAAGGGT | |||

| Hoxa11 | Forward: ATAGCACGGTGGGCAGGAACG Reverse: AGTCGGAGGAAGCGAGGTTTT | 62 | NM_010450 |

| Ihh | Forward: CTACAATCCCGACATCATCTTCAA Reverse: CGGTCACCCGCAGTTTCA | 62 | NM_001313683 |

| COX2 | Forward: ACCTGGTGAACTACGACTGCTA Reverse: CCTGGTCGGTTTGATGTTACTG | 59 | YP_00168670 |

| LIF | Forward: CTGACACCTTTCGCTTTCCTC Reverse: ACTTTCCACCTGTTTGTTCTGC | 60 | NM_001257135 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guan, S.; Xie, L.; Ma, T.; Lv, D.; Jing, W.; Tian, X.; Song, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, X.; Liu, G. Effects of Melatonin on Early Pregnancy in Mouse: Involving the Regulation of StAR, Cyp11a1, and Ihh Expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18081637

Guan S, Xie L, Ma T, Lv D, Jing W, Tian X, Song Y, Liu Z, Xiao X, Liu G. Effects of Melatonin on Early Pregnancy in Mouse: Involving the Regulation of StAR, Cyp11a1, and Ihh Expression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017; 18(8):1637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18081637

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuan, Shengyu, Lu Xie, Teng Ma, Dongying Lv, Wang Jing, Xiuzhi Tian, Yukun Song, Zhiping Liu, Xianghong Xiao, and Guoshi Liu. 2017. "Effects of Melatonin on Early Pregnancy in Mouse: Involving the Regulation of StAR, Cyp11a1, and Ihh Expression" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, no. 8: 1637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18081637