Transcriptome Analysis of Kiwifruit in Response to Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae Infection

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. De Novo RNA-Seq Assembly and Annotation of Unigenes

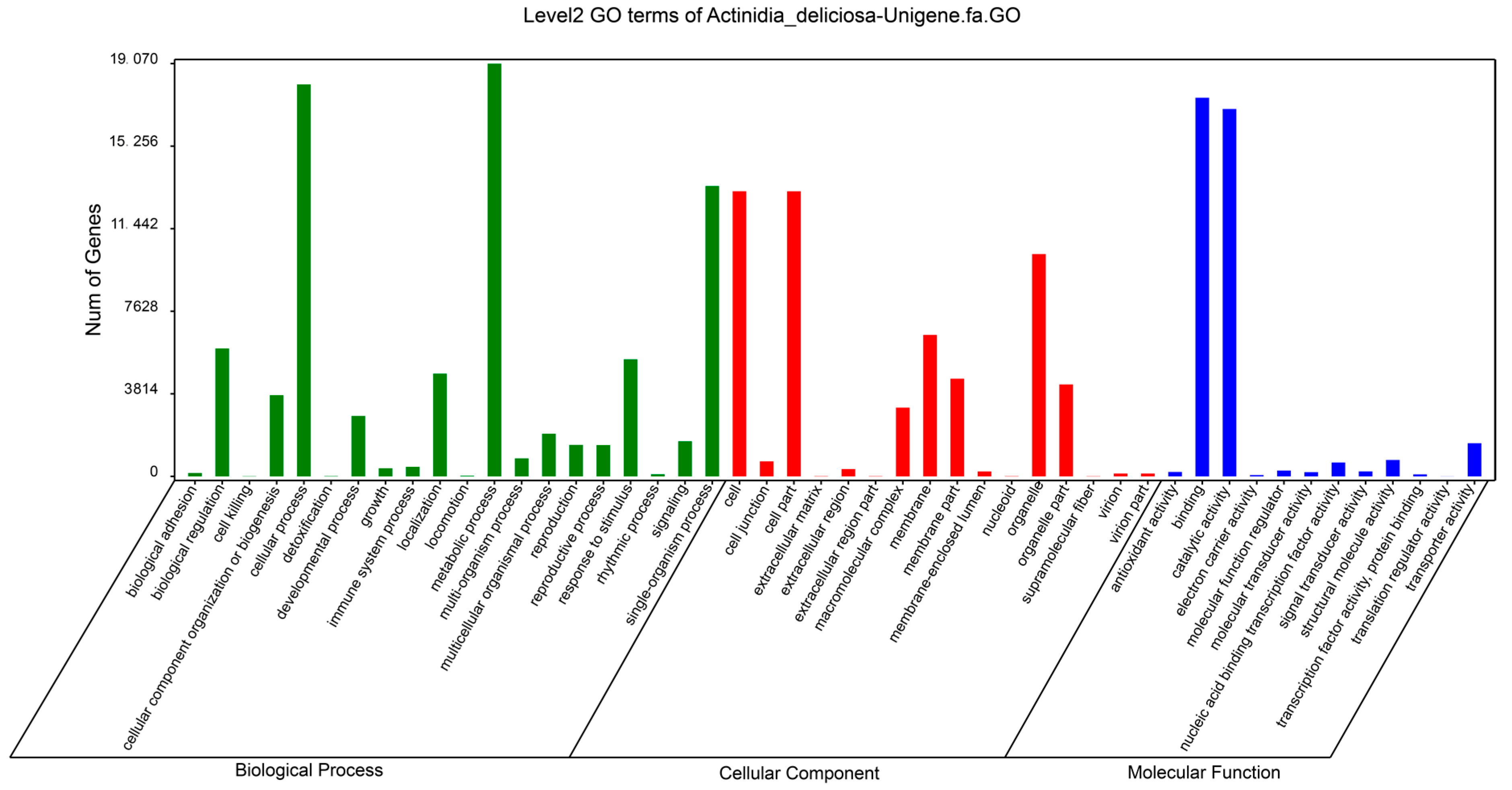

2.2. Functional Classification of Unigenes

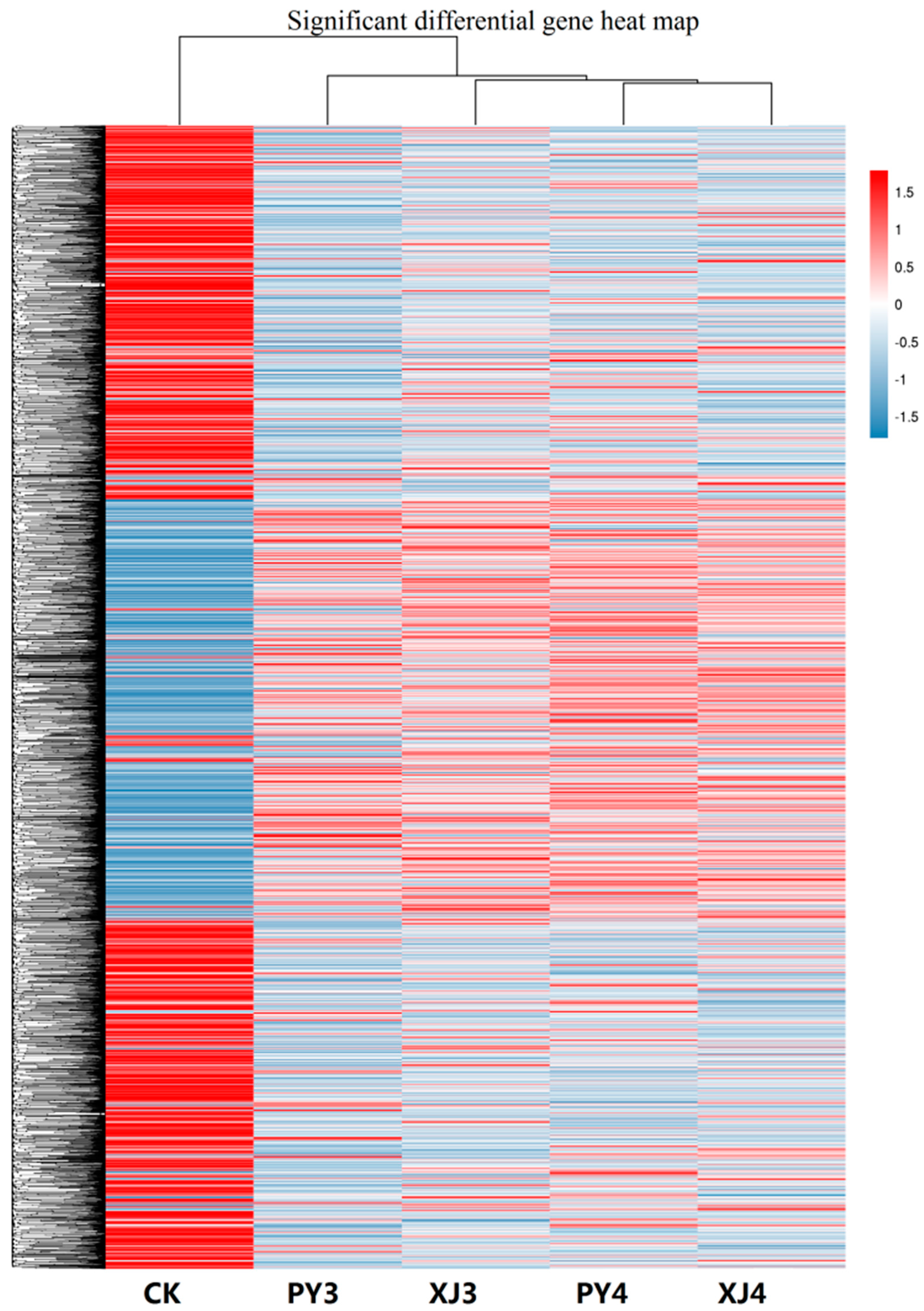

2.3. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Unigenes

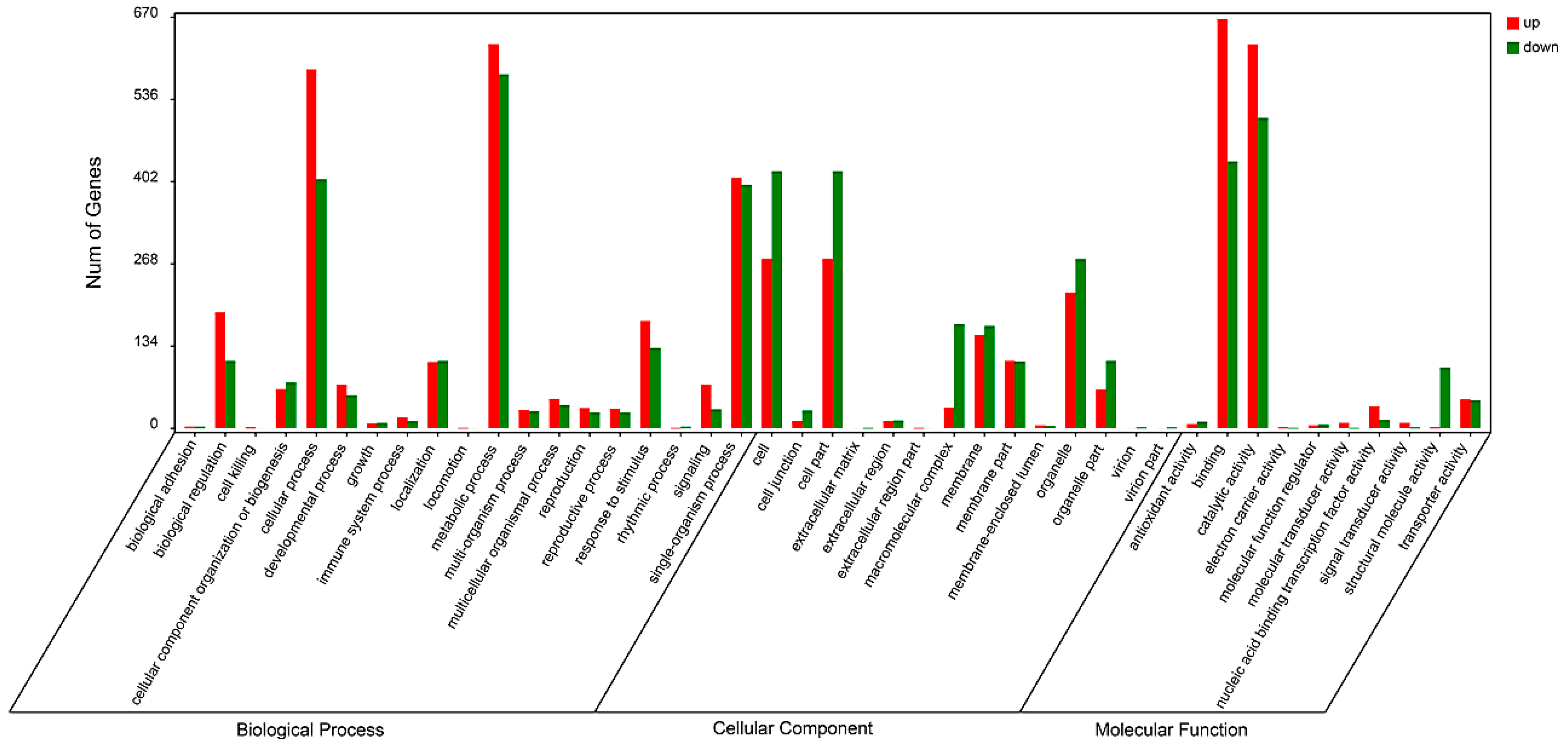

2.4. Functional Classification of Differentially Expressed Genes

2.5. Analysis of Genes in Plant-Pathogen Interaction

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

4.2. RNA Extraction, Transcriptome Sequencing and De Novo Assembly

4.3. Functional Annotation of Unigenes

4.4. Functional Analysis of Differentially Expressed Unigenes

4.5. Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Serizawa, S.; Ichikawa, T.; Takikawa, Y.; Tsuyumu, S.; Goto, M. Occurrence of bacterial canker of kiwifruit in Japan, description of symptoms, isolation of the pathogen and screening of bacteriocides. Jpn. J. Phytopathol. 1989, 55, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, J.L.; Yu, J.; Cornish, D.A.; Tanner, D.J.; Windner, R. Identification, virulence and distribution of two biovars of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae in New Zealand. Plant Dis. 2013, 97, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J.R.; Taylor, R.K.; Weir, B.S.; Romberg, M.K.; Vanneste, J.L. Phylogenetic relationships among global populations of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae. Phytopathology 2012, 102, 1034–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanneste, J.L.; Poliakoff, F.; Audusseau, C.; Cornish, D.A.; Paillard, S. First report of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae, the causal agent of bacterial canker of kiwifruit in France. Plant Dis. 2011, 95, 1311–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boller, T.; Felix, G. A renaissance of elicitors, perception of microbe-associated molecular patterns and danger signals by pattern-recognition receptors. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2009, 60, 379–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfano, J.R.; Collmer, A. Type III secretion system effector proteins, double agents in bacterial disease and plant defense. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2004, 42, 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Tian, F.; Wamboldt, Y.; Alfano, J.R. The majority of the type iii effector inventory of pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato dc3000 can suppress plant immunity. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 2009, 22, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisholm, S.T.; Coaker, G.; Day, B.; Staskawicz, B.J. Host-microbe interactions, shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell 2006, 124, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, J.T.; Yao, N. The role and regulation of programmed cell death in plant-pathogen interactions. Cell. Microbiol. 2004, 6, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mccann, H.C.; Rikkerink, E.H.A.; Bertels, F.; Fiers, M.; Lu, A.; Reesgeorge, J. Genomic analysis of the kiwifruit pathogen pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae provides insight into the origins of an emergent plant disease. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scortichini, M.; Marcelletti, S.; Ferrante, P.; Petriccione, M.; Firrao, G. Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae: A re-emerging, multi-faceted, pandemic pathogen. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcelletti, S.; Ferrante, P.; Petriccione, M.; Firrao, G.; Scortichini, M. Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae draft genome comparisons reveal strain-specific features involved in adaptation and virulence to Actinidia species. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrios, G.N. How plants defend themselves against pathogens. In Plant Pathology; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 105–160. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, P.N.; Rathjen, J.P. Plant immunity, towards an integrated view of plant-pathogen interactions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, R.N.; Wallsgrove, R.M. Tansley Review No. 72. Secondary metabolites in plant defence mechanisms. New Phytol. 1994, 127, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Peterson, C.J.; Coats, J.R. Fumigation toxicity of monoterpenoids to several stored product insects. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2003, 39, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, K.A.; Carson, C.F.; Riley, T.V. Antifungal activity of the components of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 95, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, M.; Henika, P.R.; Mandrell, R.E. Bactericidal activities of plant essential oils and some of their isolated constituents against Campylobacter jejuni, Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, and Salmonella enterica. J. Food Prot. 2002, 65, 1545–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruyne, L.D.; Hfte, M.; Vleesschauwer, D.D. Connecting growth and defense: The emerging roles of brassinosteroids and gibberellins in plant innate immunity. Mol. Plant 2014, 7, 943–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canfield, L.M.; Forage, J.W.; Valenzuela, J.G. Carotenoids as cellular antioxidants. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1992, 200, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slatnar, A.; Mikulič-Petkovšek, M.; Veberič, R.; Štampar, F. Research on the involment of phenoloics in the defence of horticultural plants. Acta Agric. Slov. 2016, 107, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.B.; Cho, B.H.; Næsby, M.; Gregersen, P.L.; Brandt, J.; Madrizordeñana, K.; Collinge, D.B.; Thordal-Christensen, H. The molecular characterization of two barley proteins establishes the novel pr-17 family of pathogenesis-related proteins. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2002, 3, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatrice, C.; Linthorst, J.M.H.; Cinzia, F.; Luca, R. Enhancement of PR1, and PR5, gene expressions by chitosan treatment in kiwifruit plants inoculated with pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2017, 148, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anu, K.; Jessymol, K.K.; Chidambareswaren, M.; Gayathri, G.S.; Manjula, S. Down-regulation of osmotin (PR5) gene by virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) leads to susceptibility of resistant piper colubrinum link. to the oomycete pathogen phytophthora capsici leonian. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 53, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bertini, L.; Leonardi, L.; Caporale, C.; Tucci, M.; Cascone, N.; Berardino, I.D.; Buonocore, V.; Caruso, C. Pathogen-responsive wheat PR4 genes are induced by activators of systemic acquired resistance and wounding. Plant Sci. 2003, 164, 1067–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, Y.R.; Keshgond, R.S. Role of pathogenesis-related proteins in plant disease management—A review. Agric. Rev. 2013, 34, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Vriens, K.; Cammue, B.P.; Thevissen, K. Antifungal plant defensins: Mechanisms of action and production. Molecules 2014, 19, 12280–12303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egorov, T.A.; Odintsova, T.I.; Pukhalsky, V.A.; Grishin, E.V. Diversity of wheat anti-microbial peptides. Peptides 2005, 26, 2064–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindschedler, L.V.; Whitelegge, J.P.; Millar, D.J.; Bolwell, G.P. A two component chitin-binding protein from french bean—Association of a proline-rich protein with a cysteine-rich polypeptide. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 1541–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneshmand, F.; Zare-Zardini, H.; Ebrahimi, L. Investigation of the antimicrobial activities of Snakin-Z, a new cationic peptide derived from Zizyphus jujuba fruits. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 2292–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tameling, W.I.; Elzinga, S.D.; Darmin, P.S.; Vossen, J.H.; Takken, F.L.; Haring, M.A.; Cornelissen, B.J. The tomato R gene products I-2 and MI-1 are functional ATP binding proteins with ATPase activity. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 2929–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luck, J.E.; Lawrence, G.J.; Dodds, P.N.; Shepherd, K.W.; Ellis, J.G. Regions outside of the leucine-rich repeats of flax rust resistance proteins play a role in specificity determination. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Yuan, F.; Leister, R.T.; Ausubel, F.M.; Katagiri, F. Mutational analysis of the Arabidopsis nucleotide binding site-leucine-rich repeat resistance gene RPS2. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 2541–2554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yee, D.; Goring, D.R. The diversity of plant U-box E3 ubiquitin ligases, from upstream activators to downstream target substrates. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 1109–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, A.; Ewan, R.; Mesmar, J.; Gudipati, V.; Sadanandom, A. E3 ubiquitin ligases and plant innate immunity. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzálezlamothe, R.; Tsitsigiannis, D.I.; Ludwig, A.A.; Panicot, M.; Shirasu, K.; Jones, J.D. The U-box protein CMPG1 is required for efficient activation of defense mechanisms triggered by multiple resistance genes in tobacco and tomato. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 1067–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aravind, L.; Koonin, E.V. The U box is a modified RING finger—A common domain in ubiquitination. Curr. Biol. 2000, 10, R132–R134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorick, K.L.; Jensen, J.P.; Fang, S.; Ong, A.M.; Hatakeyama, S.; Weissman, A.M. Ring fingers mediate ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2)-dependent ubiquitination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 11364–11369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Ahn, I.P.; Ning, Y.; Park, C.H.; Zeng, L.; Whitehill, J. The U-box/ARM E3 ligase PUB13 regulates cell death, defense and flowering time in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2012, 159, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.; Lin, W.; Gao, X.; Wu, S.; Cheng, C.; Avila, J. Direct ubiquitination of pattern recognition receptor FLS2 attenuates plant innate immunity. Science 2011, 332, 1439–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J M.; Chai, J. Plant pathogenic bacterial type III effectors subdue host responses. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2008, 11, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardan, L.; Shafik, H.; Belouin, S.; Broch, R.; Grimont, F.; Grimont, P.A. DNA relatedness among the pathovars of Pseudomonas syringae and description of Pseudomonas tremae sp. nov. and Pseudomonas cannabina sp. nov. (ex Sutic and Dowson 1959). Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1999, 49, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteil, C.L.; Cai, R.; Liu, H.; Llontop, M.E.; Leman, S.; Studholme, D.J. Nonagricultural reservoirs contribute to emergence and evolution of pseudomonas syringae crop pathogens. New Phytol. 2013, 199, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; Ohura, I.; Kawakita, K.; Yokota, N.; Fujiwara, M.; Shimamoto, K. Calcium-dependent protein kinases regulate the production of reactive oxygen species by potato NADPH oxidase. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 1065–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurusu, T.; Kuchitsu, K.; Tada, Y. Plant signaling networks involving Ca2+ and Rboh/Nox-mediated ROS production under salinity stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eulgem, T. Regulation of the Arabidopsis defense transcriptome. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naoumkina, M.; He, X.; Dixon, R. Elicitor-induced transcription factors for metabolic reprogramming of secondary metabolism in Medicago truncatula. BMC Plant Biol. 2008, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, J.; Zhang, S.; Stacey, G. Activation of a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in Arabidopsis by chitin. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2004, 5, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Mosher, S.; Fan, B.; Klessig, D.; Chen, Z. Functional analysis of Arabidopsis WRKY25 transcription factor in plant defense against Pseudomonas syringae. BMC Plant Biol. 2007, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Loh, Y.T.; Bressan, R.A.; Martin, G.B. The tomato gene pti1encodes a serine/threonine kinase that is phosphorylated by pto and is involved in the hypersensitive response. Cell 1995, 83, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K. Functional analysis of tomato Pti4 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2002, 128, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.G.; Da, C.L.; Mcfall, A.J.; Belkhadir, Y.; Debroy, S.; Dangl, J.L. Two pseudomonas syringae type III effectors inhibit RIN4-regulated basal defense in Arabidopsis. Cell 2005, 121, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, A.; Casais, C.; Ichimura, K.; Shirasu, K. HSP90 interacts with RAR1 and SGT1 and is essential for RPS2-mediated disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 11777–11782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, B.H.; Zhang, J.Y.; Gao, Z.H.; Qu, S.C.; Tong, Z.G.; Mi, L.; Qiao, Y.S.; Zhang, Z. An improved method for isolation of total RNA from the leaves of Fragaria spp. Jiangsu J. Agric. Sci. 2008, 24, 875–877. [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conesa, A.; Götz, S.; Garcíagómez, J.M.; Terol, J.; Talón, M.; Robles, M. Blast2GO, a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3674–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Fang, L.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z. WEGO: A web tool for plotting Go annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortazavi, A.; Williams, B.A.; Mccue, K.; Schaeffer, L.; Wold, B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C (T)) method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Number of Unigenes | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Nr | 49,897 | 45.31 |

| Swissprot | 34,331 | 31.17 |

| KOG | 30,430 | 27.63 |

| KEGG | 20,524 | 18.64 |

| Annotation gene | 50,305 | 45.68 |

| Without annotation gene | 59,829 | 54.32 |

| Total unigenes | 110,134 | 100.00 |

| GO ID | Description | DEGs Genes with Pathway Annotation (1521) | All Genes with Pathway Annotation (24,936) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Terpene biosynthetic process | 7 | 7 |

| 2 | Tricarboxylic acid metabolic process | 20 | 120 |

| 3 | Regulation of defense response | 15 | 77 |

| 4 | Terpene metabolic process | 7 | 19 |

| 5 | Citrate metabolic process | 19 | 119 |

| 6 | Regulation of response to stress | 15 | 84 |

| 7 | Acetate metabolic process | 5 | 18 |

| 8 | Positive regulation of microtubule Polymerization or depolymerization | 2 | 2 |

| 9 | Metabolic process | 1203 | 19,066 |

| 10 | Lignin metabolic process | 5 | 21 |

| 11 | Apoptotic process | 2 | 3 |

| 12 | Regulation of cell size | 2 | 3 |

| 13 | phenylpropanoid metabolic process | 15 | 128 |

| 14 | Cellular amino acid catabolic process | 6 | 33 |

| 15 | Response to bacterium | 27 | 282 |

| 16 | Energy coupled proton transmembrane Transport, against electrochemical gradient | 11 | 88 |

| 17 | Nucleoside diphosphate metabolic process | 5 | 26 |

| 18 | Cellular respiration | 11 | 89 |

| 19 | Regulation of multi-organism process | 3 | 10 |

| 20 | Arachidonic acid metabolic process | 2 | 4 |

| Metabolites | Pathway ID | Pathway | DEGs Genes with Pathway Annotation (925) | All Genes with Pathway Annotation (11,433) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenes | ko00902 | Monoterpenoid biosynthesis | 8 (0.86%) | 17 (0.15%) |

| ko00903 | Limonene and pinene degradation | 8 (0.86%) | 32 (0.28%) | |

| ko00904 | Diterpenoid biosynthesis | 8 (0.86%) | 32 (0.28%) | |

| ko00909 | Sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis | 4 (0.43%) | 17 (0.15%) | |

| ko00906 | Carotenoid biosynthesis | 8 (0.86%) | 51 (0.45%) | |

| ko00905 | Brassinosteroid biosynthesis | 2 (0.22%) | 17 (0.15%) | |

| ko00900 | Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis | 9 (0.97%) | 117 (1.02%) | |

| Phenols | ko00940 | Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | 64 (6.92%) | 317 (2.77%) |

| ko00380 | Tryptophan metabolism | 28 (3.03%) | 105 (0.92%) | |

| ko00350 | Tyrosine metabolism | 14 (1.51%) | 86 (0.75%) | |

| ko00360 | Phenylalanine metabolism | 9 (0.97%) | 84 (0.73%) | |

| ko00941 | Flavonoid biosynthesis | 9 (0.97%) | 91 (0.8%) | |

| ko00944 | Flavone and flavonol biosynthesis | 1 (0.11%) | 11 (0.1%) | |

| ko00400 | Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis | 6 (0.65%) | 89 (0.78%) | |

| Alkaloids | ko00950 | Isoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis | 7 (0.76%) | 39 (0.34%) |

| ko00960 | Tropane, piperidine and pyridine alkaloid biosynthesis | 4 (0.43%) | 42 (0.37%) |

| Family | Properties | All Expressed Unigenes | Differentially Expressed Unigenes |

|---|---|---|---|

| PR-1 | Unknown | 6 | 2 |

| PR-2 | β-1,3-glucanase | 1 | 0 |

| PR-4 | Chitinase type I, II | 2 | 1 |

| PR-5 | Thaumatin-like | 39 | 6 |

| PR-6 | Proteinase-inhibitor | 9 | 0 |

| PR-9 | Peroxidase | 96 | 8 |

| PR-10 | “Ribonuclease-like” | 1 | 1 |

| PR-12 | Defensin | 3 | 1 |

| PR-13 | Thionin | 3 | 0 |

| PR-14 | Lipid-transfer protein | 21 | 0 |

| Class | Number of All Identified Resistant Gene | Number of Differentially Expressed Genes |

|---|---|---|

| CN | 123 | 6 |

| CNL | 411 | 25 |

| L | 19 | 0 |

| Mlo-like | 34 | 0 |

| N | 706 | 36 |

| NL | 828 | 69 |

| Other | 93 | 8 |

| PTO | 2 | 1 |

| Pro-like | 74 | 4 |

| RLK | 281 | 20 |

| RLK-GNK2 | 246 | 13 |

| RLK-Kinase | 1 | 0 |

| RLK-Malectina | 1 | 0 |

| RLK-Pro-like | 1 | 0 |

| RLP | 1265 | 60 |

| RLP-Malectin | 5 | 0 |

| RLP-Malectina | 1 | 0 |

| RPW8-NL | 11 | 1 |

| T | 98 | 5 |

| TNL | 572 | 35 |

| TNL-OT | 1 | 0 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, T.; Wang, G.; Jia, Z.-H.; Pan, D.-L.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Guo, Z.-R. Transcriptome Analysis of Kiwifruit in Response to Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19020373

Wang T, Wang G, Jia Z-H, Pan D-L, Zhang J-Y, Guo Z-R. Transcriptome Analysis of Kiwifruit in Response to Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae Infection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018; 19(2):373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19020373

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Tao, Gang Wang, Zhan-Hui Jia, De-Lin Pan, Ji-Yu Zhang, and Zhong-Ren Guo. 2018. "Transcriptome Analysis of Kiwifruit in Response to Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae Infection" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19, no. 2: 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19020373