1. Introduction

The high sugar consumption in the modern diet has been commonly associated with chronic health consequences including risk of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and fatty liver disease [

1]. Nowadays, two out of three adults and one out of three children in the United States are overweight or obese [

2,

3] due to the high level of sugar consumption. In the same way, in the European Union 52% of the adult population is now overweight, of which 17% is obese and more than 15% of adolescents in southern European countries are obese [

4].

It is also worth mentioning that in the food industry more manufacturing processes are used routinely, and more sophisticated quality control methods are needed to ensure that every ingredient maintains its quality and safety through all processing stages. As a result, analytes like sugars, alcohols, phenols, oligonucleotides, and O

2 need to be measured at multiple stages of the production process and also in the final product. Moreover, the increasing number of food safety regulations related to alimentary allergens and contaminants require extensive control of different analytes, such as lactose [

5] or glutamate [

6] among others [

7].

Numerous methods are reported for these analyses in food [

8,

9,

10,

11]; among them, Colorimetry and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) are well-established and accepted tools for glucose determination in food matrices. However, most of the adopted methods are time consuming, expensive and require specialized personnel. In addition, the presence of interfering species in the sample matrix implies complex sample preparation processes, such as solid phase extraction (SPE) or chemical modifications (e.g., fluorescent functionalization). These sample treatments increase the complexity, time, and cost of the analysis. Therefore, development of fast, cheap, practical, and selective methods for detecting glucose in food is still a research area. In this context, electrochemical biosensors have attracted much attention due to their promising characteristics that fulfill these market demands. Moreover, due to their outstanding features, sensors presenting nano-engineered electrochemical interfaces have gained interest.

Leland C. Clark Jr. and Champ Lyons introduced in 1962 the principle of the first enzyme electrode with immobilized glucose oxidase [

12]. Following some improvements, the biosensor was launched onto the market in 1975 by the Yellow Springs Instruments Co. (Yellow Springs, OH, USA). This device was specifically designed and used for fast glucose analysis in blood samples from diabetics. Since then, the biosensor field has experienced important growth. In this context, amperometric glucose biosensors offer great potential for their use in the food production and processing industry.

Amperometric glucose biosensors are prepared by immobilizing glucose oxidase (GOx) molecules onto an electrochemical interface. The enzyme catalyzes the conversion of glucose to gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide. Glucose is quantified by the electrochemical measurement of hydrogen peroxide. One of the most important factors for the proper functioning of the biosensor is the correct selection of the electrochemical interface where the enzyme is immobilized. Recent researchers focused on the use of electrical conductors or semiconductor nanomaterials as biosensor interfaces [

13,

14]. The high surface area of nanomaterials allows immobilization of a large number of enzyme molecules, significantly increasing the sensitivity of the sensor [

15]. Among all nanomaterials, titanium dioxide has been one of the most interesting materials in recent investigations [

16,

17] due to the facility to control the morphology of highly ordered titanium dioxide nanotube arrays (TiO

2NTAs). Moreover, biocompatibility and ability to promote charge transfer processes make this material suitable as an electrochemical interface [

18,

19].

TiO

2NTAs are formed by anodization from bare titanium [

20,

21,

22]. In fluoride-containing electrolytes, the anodization of Ti is accompanied with the chemical dissolution of TiO

2 due to the formation of TiF

62− anions [

23]. This formation process ends when TiO

2 dissolution and formation rates reach the equilibrium. Due to the simplicity of the anodic formation as well as for all the TiO

2NTAs properties, it has been extensively used as electrical interface for biosensor applications [

14,

17,

18,

24,

25,

26].

An important factor for the success of an enzymatic biosensor is the enzyme immobilization strategy. This process provides an intimate contact between the enzyme and the electrode surface. The objective is to maintain or improve the enzyme stability, properties, and the active structural conformation, as well as to allow the substrate to arrive at the active center of the enzyme [

27]. Different physical and chemical immobilization techniques can be used to achieve this goal: surface adsorption, electrostatic interactions, covalent binding or polymer entrapment [

28,

29,

30,

31]. One of the simplest approaches is to entrap the enzyme within a gel layer, for example using Chitosan which is a biocompatible and biodegradable hydrogel [

32,

33,

34] and contributes to stabilizing the enzyme molecules [

31,

35].

Several biosensor designs can be found in literature for glucose analysis in food stuff [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Usually, authors focus their efforts on new architectures to overcome matrix interferences or to modify the sensors’ linear range and sensitivity, as well as to keep the enzyme active as long as possible. However, there is a general lack of information in literature on other fundamental analytical parameters, like specificity, precision, accuracy, and robustness. These parameters must be deeply evaluated to prove both that a new measuring method or tool is capable of producing accurate results and to fulfill the quality assurance requirements of the food industry.

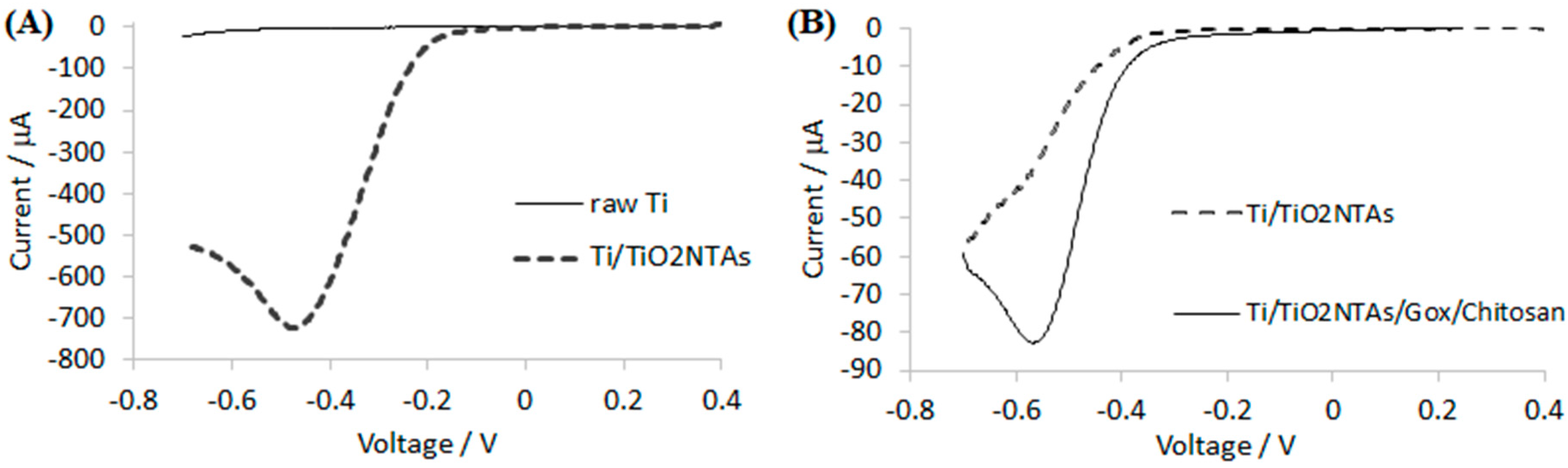

The goal of this work is to evaluate the analytical parameters of a biosensor to measure glucose in four different food products: soft drinks, soy sauces, dairy products and tomato sauces. The analyses have been performed using an amperometric glucose biosensor based on GOx immobilization with a polymeric hydrogel (Chitosan) onto highly ordered titanium dioxide nanotube arrays (TiO2NTAs). This sensor architecture was selected due to its simplicity and relative low cost.

2. Materials and Methods

Titanium (99.7%, 5 mm diameter) was supplied by Alfa Aesar (Black Friel, MA, USA). Ethylene glycol (EG), ammonium fluoride and hydrogen peroxide were supplied by Panreac. Glucose, GOx (type: VII, Aspergillus niger, 100 units/mg) (ref. 101404648) and a low molecular weight Chitosan (ref. 1001654970) were supplied by Sigma Aldrich. The supporting electrolyte was 0.1 M pH 7.0 phosphate buffer solution (PBS).

The electrode morphology was characterized using a field emission scanning electron microscope (JEOL JSM-7001F, Tokyo, Japan). Linear sweep and amperometric measurements were performed in a standard three-electrode configuration (Ag/AgCl/3 M KCl was used as a reference electrode). All potentials mentioned in this work are referred to as the reference electrode. Experiments were performed using a potentiostat Autolab PGSTAT 302N and the working electrode was mounted in a rotating disc electrode system EG&G PARC model 616.

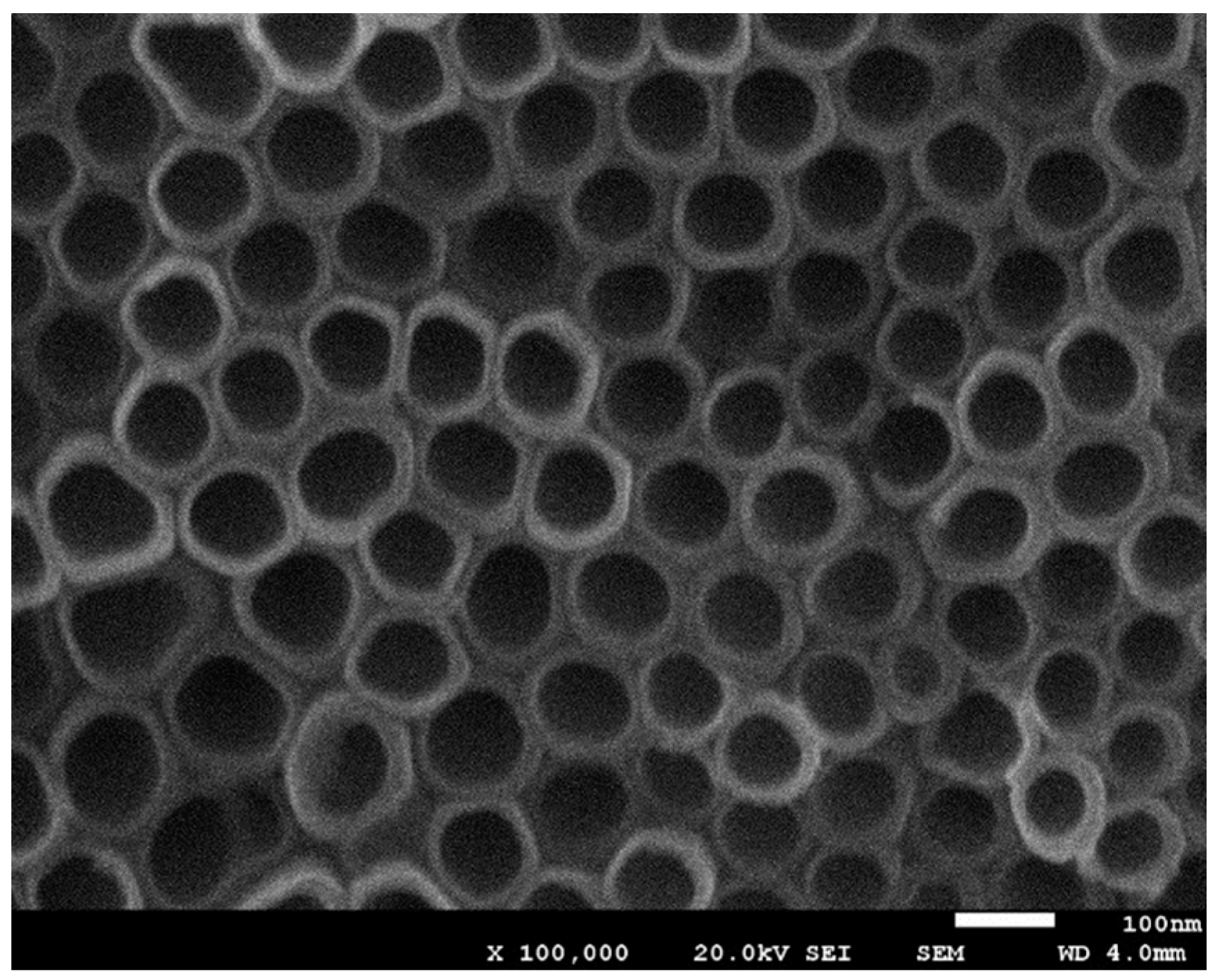

2.1. Synthesis of TiO2 Nanotubes Array

TiO

2 nanotubes arrays were synthesized onto the Ti substrates by anodic oxidation. First of all, pure titanium disks were polished with SiC paper (2000 grit) and then were cleaned in ethanol prior to anodization. The cleaned Ti disks were anodized in a two-electrode electrochemical cell in ethylene glycol solution containing 0.3% NH

4F and 2% H

2O at 35 V for 17 h. This anodization time yields the maximum sensitivity of the sensor. Higher times result in the nanotube walls collapse. Then, the prepared electrode was sonicated during 30 s in water to remove surface debris. Finally, a thermal annealing was performed at 500 °C for 3 h in air to crystallize TiO

2 nanotubes from amorphous to anatase phase [

44].

2.2. Preparation of the Biosensor

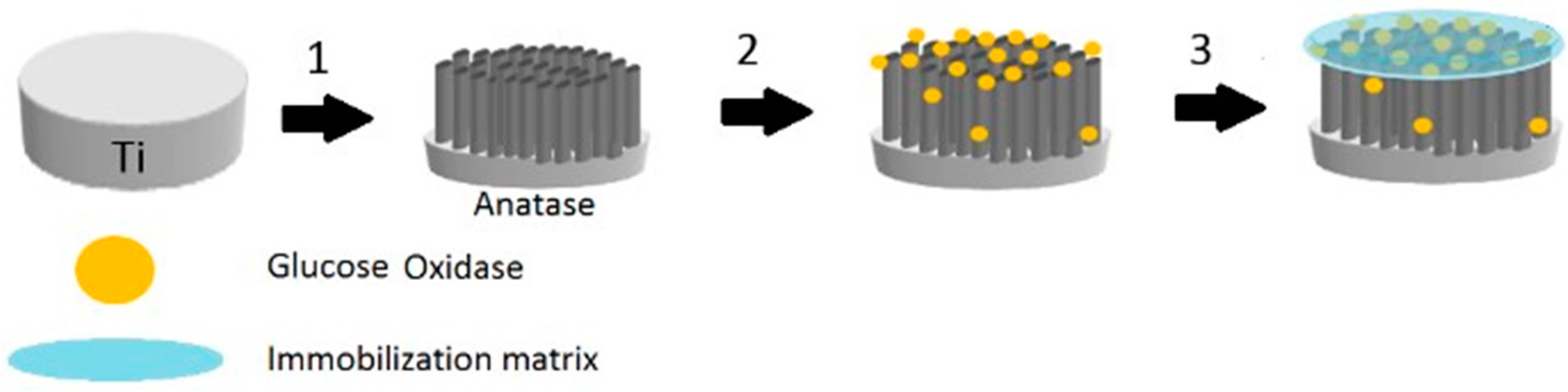

The immobilization of GOx on the modified TiO

2 nanotubes array electrode (TiO

2NTAs/Ti) was carried out by physical methods. An enzyme solution was prepared by dissolving 15 mg of GOx in 500 μL of 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.0). Then, the enzyme solution was immobilized onto the modified electrode using the hydrogel Chitosan (see

Figure 1).

A 0.5% Chitosan solution was prepared by dissolving 53 mg Chitosan in 1% acetic acid. 20 μL of GOx solution and 20 μL of Chitosan solution were deposited on a TiO2NTAs/Ti electrode, then mixed and dried with an air stream. The obtained Chitosan–GOx/TiO2NTAs/Ti biosensor was washed with PBS to eliminate the enzyme that had not been immobilized. Finally, it was immersed in PBS solution for at least 30 min to rehydrate the enzyme molecules. When the electrodes were not in use, they were kept immersed in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.0) at 4 °C.

2.3. Samples Preparation

Samples for the amperometric biosensor measurements did not need further preparations than dilution. For the soft drinks and the soy sauces, an adequate volume of the sample was directly added to the measuring chamber, containing 100 mL of 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.0). Dairy products and tomato sauces were first diluted into 50 mL of water. Then, an adequate volume of the diluted sample was directly added to the measuring chamber, containing 100 mL of 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.0). All samples were quantified by the standard additions method.

2.4. HPLC and Amperometric Measurements

Glucose was determined by HPLC using an Agilent Technologies 1200 Series Chromatograph. Separation was done using a Kromasil® 100 NH2 column with 5 μm of particle size, 250 mm longitude and 4 mm inner diameter. Elution was with 75% acetonitrile in ultrapure water. Eluted components were detected using a refraction index detector (Agilent G1362A) and quantified by direct interpolation in a calibration curve.

Soft drink samples for the HPLC analysis were prepared by diluting 10 mL into 100 mL of ultrapure water and then were filtered through 0.45 μm nylon filters. Dairy products, soy and tomato sauces were prepared by dissolving an adequate amount of sample into 50 mL of Milli-Q water, followed by 10 min ultrasonication. The resulting mixture was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant solutions were filtered through 0.22 μm filters prior to injection.

Glucose was also quantified in the test sample using an amperometric/enzymatic titration method [

45,

46]. In this analytical method, GOx catalyzes the oxidation of glucose by dissolved oxygen to yield gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide (Equation (1)). Then, hydrogen peroxide reacted with iodide to produce iodine in presence of molybdate as a catalyst (Equation (2)).

The iodine formation is followed continuously by monitoring the current in a two-electrode system (Pt electrodes) by applying a constant potential of 100 mV. Under these conditions, the slope of the curve current vs. time is proportional to the glucose concentration. Then, a calibration curve can be constructed by plotting the slopes vs. the glucose concentration. This method has been thoroughly explained in the literature [

45,

46]. The glucose content in the test sample was determined by direct interpolation in the calibration curve.

4. Conclusions

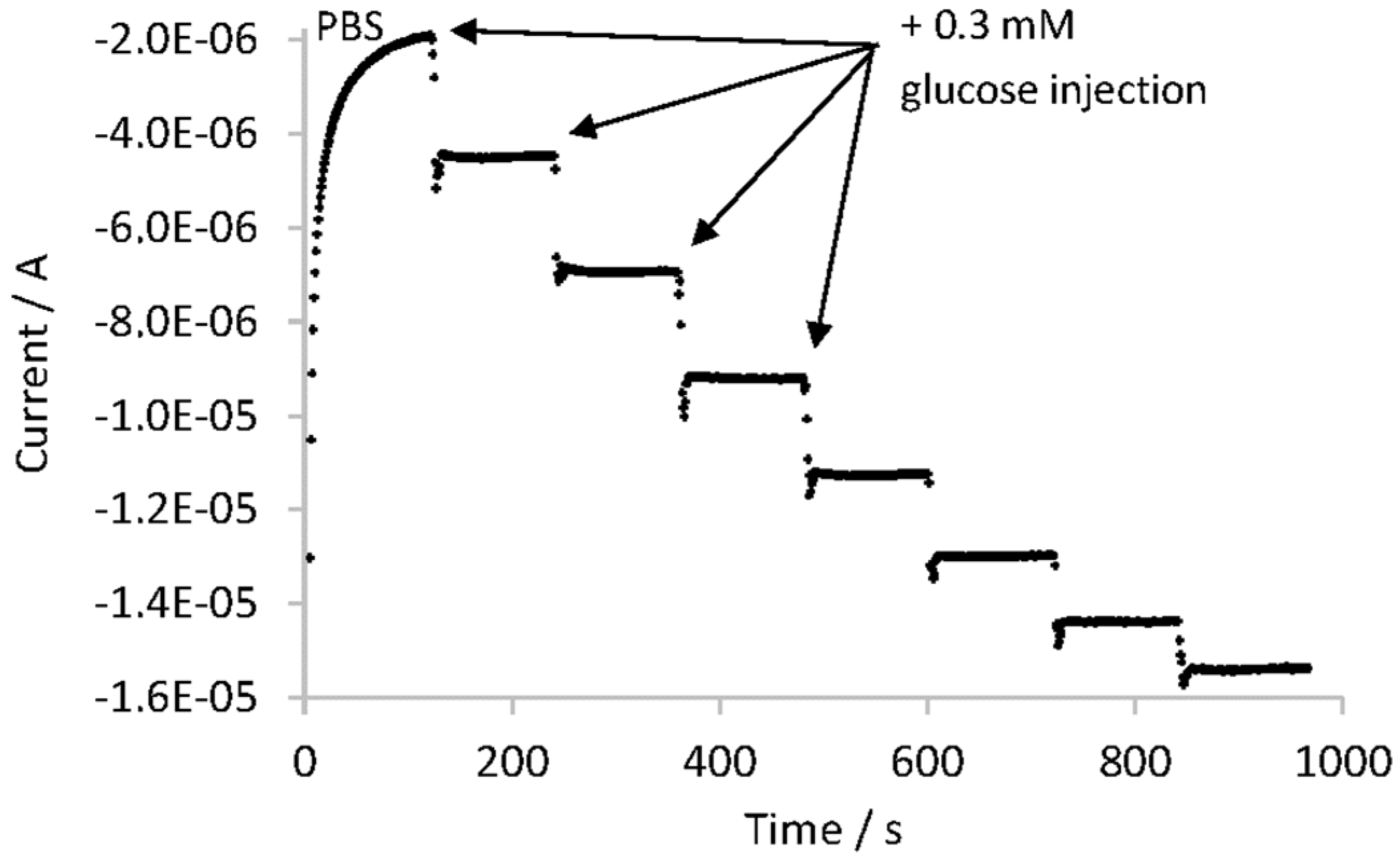

The analytical parameters of the Chitosan–Ox/TiO2NTAs/Ti biosensor were evaluated using a commercial lemon soft drink as a test sample. This biosensor showed a linear range from 0.3 mM to 1.5 mM of glucose with a low limit of detection (0.07 mM), low limit of quantification (0.30 mM) and high sensitivity (5.46 μA·mM−1). The measured glucose concentration of the sample showed a good agreement with other analytical techniques: the deviation from HPLC was 6.4% and from an amperometric/enzymatic titration 1.6%. Measurements done with the studied biosensor showed high repeatability (RSD equal to 0.8%), high reproducibility (RSD equal to 2.5%), high robustness and small analysis time (less than 10 min). In addition, the biosensor had good selectivity towards common interfering species in food matrices, such us ascorbic acid, citric acid and fructose. Finally, the storage stability was further examined and after 30 days, the GOx–Chitosan/TiO2NTAs biosensor retained 85% of its initial current response.

The biosensor was used to determine the glucose concentration in four different types of alimentary samples (soft drinks, soy sauces, dairy products and tomato sauces). In all the cases, the glucose concentration was determined with sufficient accuracy (deviation less than 10%) regardless of the matrix composition. Therefore, it can be concluded that the electrochemical biosensor (Chitosan–GOx/TiO2NTAs/Ti) represents as a low cost, simple and rapid alternative to classical methods for glucose quantification in foodstuff.