Platform for a Hydrocarbon Exhaust Gas Sensor Utilizing a Pumping Cell and a Conductometric Sensor

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

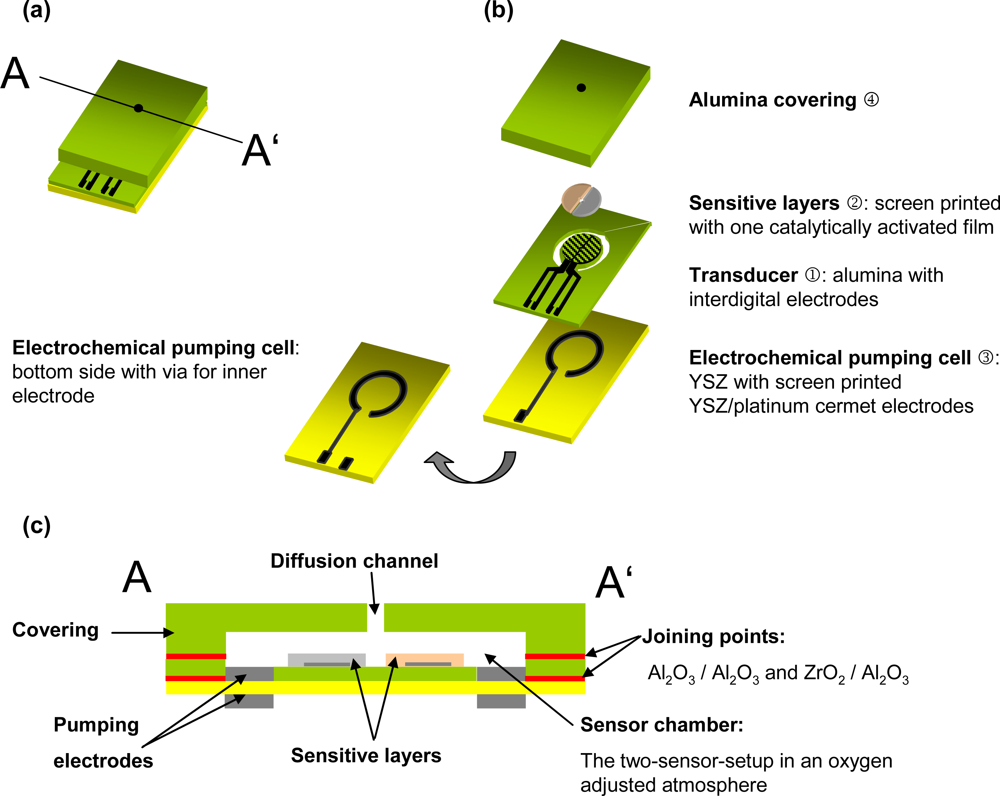

2.1. Platform Design

2.2. Activation

2.3. Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

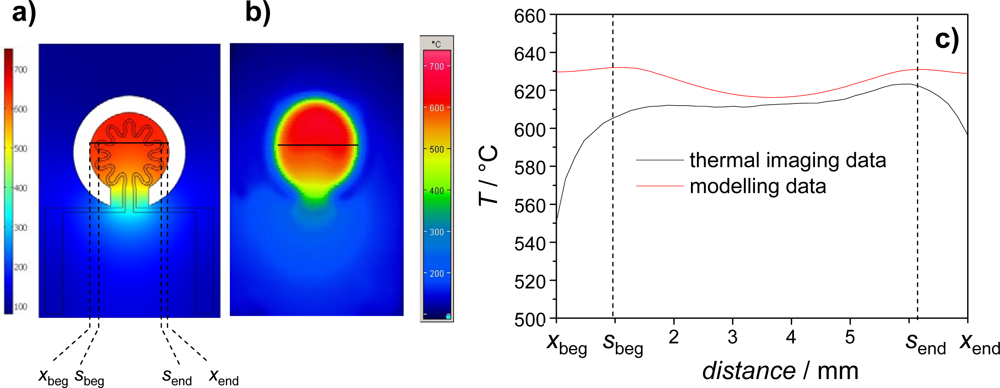

3.1. Heater

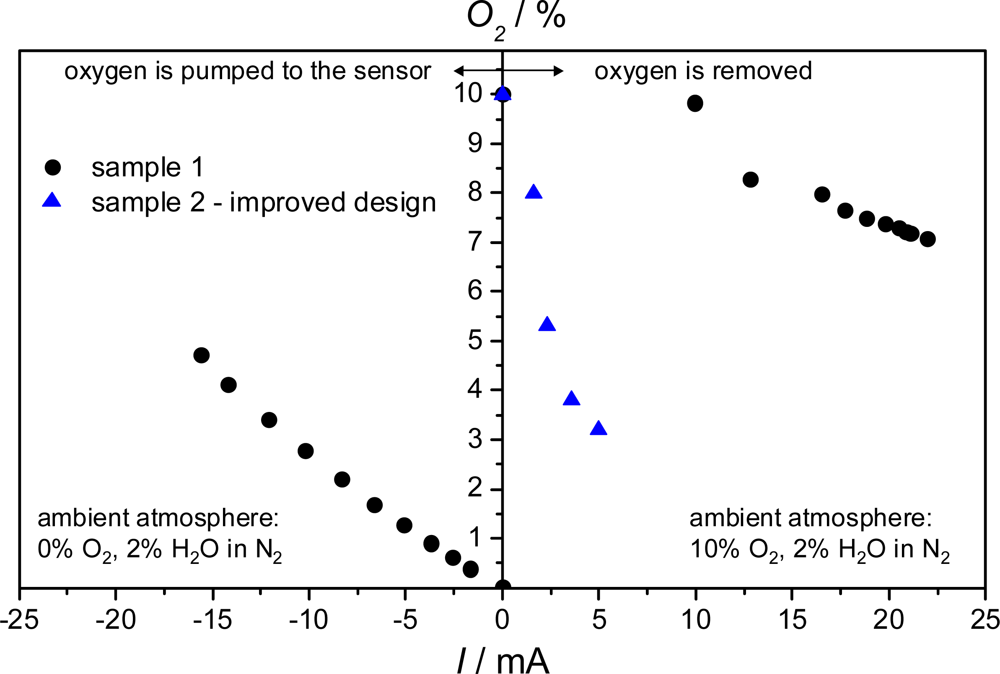

3.2. Two-Sensor-Setup

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References and Notes

- Moos, R. A brief overview on automotive exhaust gas sensors based on electroceramics. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol 2005, 2, 401–413. [Google Scholar]

- Alkemade, U.G.; Schumann, B. Engines and exhaust after treatment systems for future automotive applications. Solid State Ionics 2006, 177, 2291–2296. [Google Scholar]

- Riegel, J.; Neumann, H.; Wiedenmann, H.-M. Exhaust gas sensors for automotive emission control. Solid State Ionics 2002, 152–153, 783–800. [Google Scholar]

- Guth, U.; Zosel, J. Electrochemical solid electrolyte gas sensors - hydrocarbon and NOx analysis in exhaust gases. Ionics 2004, 10, 366–377. [Google Scholar]

- Moos, R.; Sahner, K.; Fleischer, M.; Guth, U.; Barsan, N.; Weimar, U. Solid state gas sensor research in germany—A status report. Sensors 2009, 9, 4323–4365. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, J.; Fleischer, M.; Meixner, H. Gas-sensitive electrical properties of pure and doped semiconducting Ga2O3 thick films. Sens. Actuat. B: Chem 1998, 48, 318–321. [Google Scholar]

- Sahner, K.; Moos, R.; Matam, M.; Tunney, J.; Post, M. Hydrocarbon sensing with thick and thin film p-type conducting perovskite materials. Sens. Actuat. B: Chem 2005, 108, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, M.; Meixner, H. Oxygen sensing with long-term stable Ga2O3 thin films. Sens. Actuat. B: Chem 1991, 5, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Menesklou, W.; Schreiner, H.J; Härdtl, K.H.; Ivers-Tiffée, E. High temperature oxygen sensors based on doped SrTiO3. Sens. Actuat. B: Chem 1999, 59, 184–189. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, J.; Fleischer, M.; Meixner, H. Gas-sensitive electrical properties of pure and doped semiconducting Ga2O3 thick films. Sens. Actuat. B: Chem 1998, 48, 318–321. [Google Scholar]

- Bausewein, A.; Chemisky, E.; Meixner, H.; Lemire, B.; Schürz, W. Gas Sensor and the Use thereof. World Patent Application WO 99/56118 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sahner, K.; Fleischer, M.; Magori, E.; Meixner, H.; Deerberg, J.; Moos, R. HC-sensor for exhaust gases based on semiconducting doped SrTiO3 for On-Board Diagnosis. Sens. Actuat. B: Chem 2006, 114, 861–868. [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis, E.M.; Soltis, R. Apparatus for Sensing Hydrocarbons and Carbon Monoxide. US Patent US 5,250,169,. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, J.H.; Soltis, R.E.; Rimai, L.; Logothetis, E.M. Sensors for measuring combustibles in the absence of oxygen. Sens. Actuat. B: Chem 1992, 9, 233–239. [Google Scholar]

- Biskupski, D.; Wiesner, K.; Kita, J.; Fleischer, M.; Moos, R. Automotive exhaust gas sensor based on an electrochemical cell combined with a resistive gas sensor. Sens. Lett 2008, 6, 803–807. [Google Scholar]

- Moos, R.; Menesklou, W.; Schreiner, H.J.; Härdtl, K.H. Materials for temperature independent resistive oxygen sensors for combustion exhaust gas control. Sens. Actuat. B: Chem 2000, 67, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Achmann, S.; Hagen, G.; Kita, J.; Malkowsky, I.M.; Kiener, C.; Moos, R. Metal-organic frameworks for sensing applications in the gas phase. Sensors 2009, 9, 1574–1589. [Google Scholar]

- Moos, R.; Bischoff, T.; Menesklou, W.; Härdtl, K.H. Solubility of lanthanum in strontium titanate in oxygen-rich atmospheres. J. Mat. Sci 1997, 32, 4247–4252. [Google Scholar]

- Rettig, F.; Moos, R. Ceramic meso hot-plates for gas sensors. Sens. Actuat. B: Chem 2004, 103, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Bausewein, A. Sauerstoffkompensierter Kohlenwasserstoffsensor für die Katalysatorüberwachung im Kraftfahrzeug, (Oxygen Compensated Hydrocarbon Sensor for Catalyst Monitoring in Motor Vehicles). Ph.D. thesis,. Universität der Bundeswehr, Munich, Germany, 2001.

- Moos, R.; Härdtl, K.H. Defect chemistry of donor doped and undoped strontium titanate ceramics between 1000 °C and 1400 °C. J. Am. Ceram. Soc 1997, 80, 2549–2562. [Google Scholar]

© 2009 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Biskupski, D.; Geupel, A.; Wiesner, K.; Fleischer, M.; Moos, R. Platform for a Hydrocarbon Exhaust Gas Sensor Utilizing a Pumping Cell and a Conductometric Sensor. Sensors 2009, 9, 7498-7508. https://doi.org/10.3390/s90907498

Biskupski D, Geupel A, Wiesner K, Fleischer M, Moos R. Platform for a Hydrocarbon Exhaust Gas Sensor Utilizing a Pumping Cell and a Conductometric Sensor. Sensors. 2009; 9(9):7498-7508. https://doi.org/10.3390/s90907498

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiskupski, Diana, Andrea Geupel, Kerstin Wiesner, Maximilian Fleischer, and Ralf Moos. 2009. "Platform for a Hydrocarbon Exhaust Gas Sensor Utilizing a Pumping Cell and a Conductometric Sensor" Sensors 9, no. 9: 7498-7508. https://doi.org/10.3390/s90907498