Biochemical Traits, Survival and Biological Properties of the Probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum Grown in the Presence of Prebiotic Inulin and Pectin as Energy Source

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain and Culture Conditions

2.2. Resistance to Simulated Gastric and Intestinal Juices

2.3. Preparation of Heat Killed Cells

2.4. Biochemical Analysis

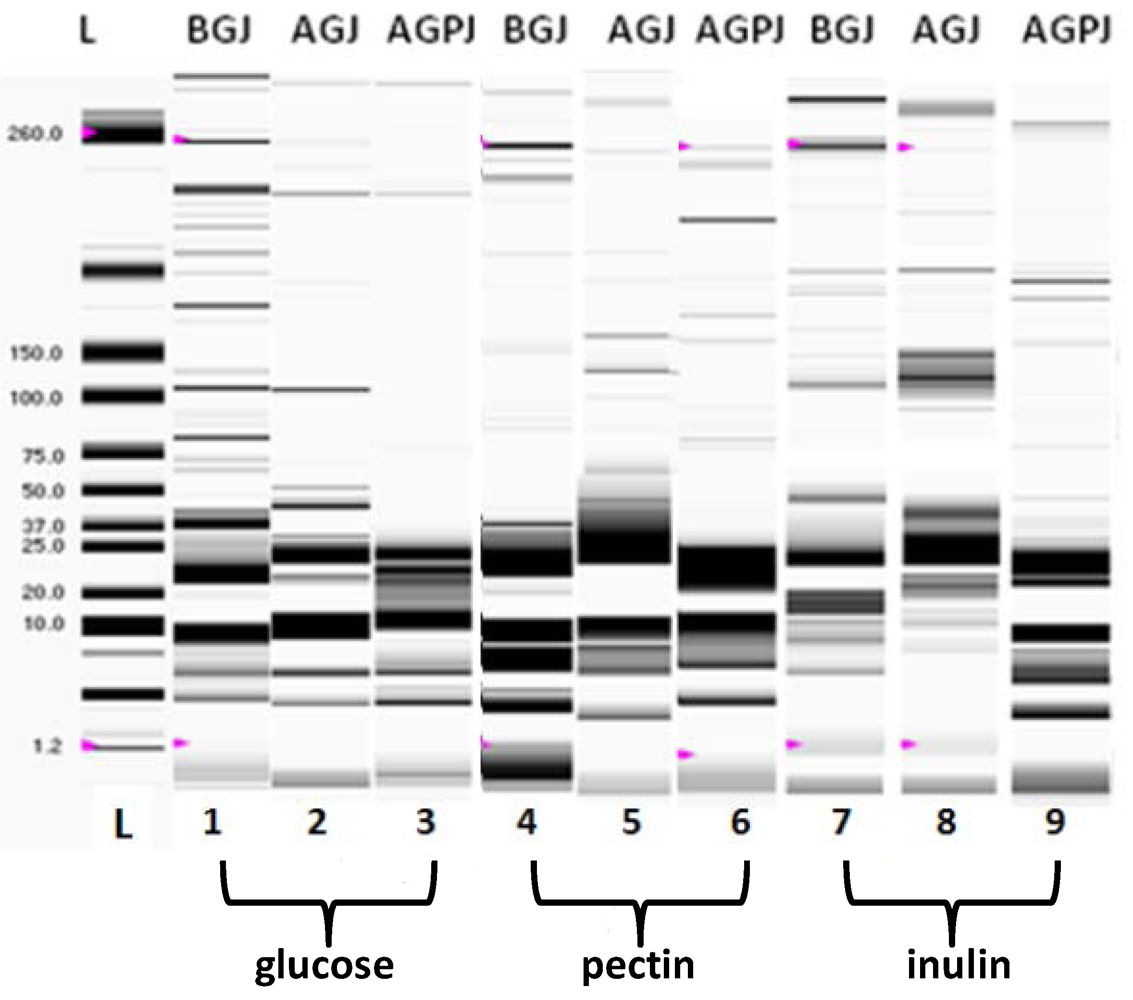

2.4.1. Protein Profile

2.4.2. Production of Short Chain Fatty Acids

2.4.3. Free Radical–Scavenging Capacity

2.4.4. Microbial Adhesion to Solvent

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Culture Growth and Resistance to Gastrointestinal Stress

3.2. Production of Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)

| Acetic acidμmol/mL ± SD | Lactic acidμmol/mL ± SD | Butyric acidμmol/mL ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 276 ± 12 | 213 ± 25 | 7.5 ± 0.52 |

| Inulin | 208 ± 20 | 162 ± 20 | 10.5 ± 0.65 |

| Pectin | 213 ± 70 | 147 ± 10 | ND |

3.3. Antioxidative Activity

3.4. Microbial Adhesion to Solvent

4. Concluding Remarks

References

- FAO/WHO Experts’ Report. Health and nutritional properties of probiotics in food including powder milk with live lactic acid bacteria, Cordoba, Argentina, 1-4 October 2001. Available online: http://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications-/fs_management/en/probiotics.pdf accessed on 15 May 2012.

- Barrett, J.S.; Canale, K.E.; Gearry, R.B.; Irving, P.M.; Gibson, P.R. Probiotic effects on intestinal fermentation patterns in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 5020–5024. [Google Scholar]

- Rafter, J. Probiotics and colon cancer. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroent. 2003, 17, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng-Liu, C.; Pan, T.M. In Vitro Effects of Lactic Acid Bacteria on Cancer Cell Viability and Antioxidant Activity. J. Food Drug Anal. 2010, 18, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ames, B. N.; Shigenaga, M. K.; Hagen, T. M. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of agin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993, 90, 7915–7922. [Google Scholar]

- Mikelsaar, M.; Zilmer, M. Lactobacillus fermentum ME-3–an antimicrobial and antioxidative probiotic. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2009, 21, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R.; Roberfroid, M.B. Dietary Modulation of the Colonic Microbiota: Introducing the Concept of Prebiotics. J. Nutr. 1995, 125, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, N.P. Functional foods from probiotics and prebiotics. Food Technol. 2001, 22, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Pool-Zobel, BL, Sauer J. Overview of experimental data on reduction of colorectal cancer risk by inulin-type fructans 1-4. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2580–2584. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz-Ahrens, K.E.; Ade, P.; Marten, B.; Weber, P.; Timm, W.; Acil, Y; Glüer, C.G.; Schrezenmeir, J. Prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics affect mineral absorption, bone mineral content,and bone structure. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 838–846. [Google Scholar]

- Brighenti, F. Inulin and oligofructose: dietary fructans and serum triacylglycerols: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2552–2556. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.; Goyal, A. Functional oligosaccharides: production, properties and applications. World J. Microbiol. Biotech. 2011, 27, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delzenne, N.M.; Daubioul, C.; Neyrinck, A.; Lasa, M.; Taper, H.S. Inulin and oligofructose modulate lipid metabolism in animals: review of biochemical events and future prospects. Brit. J. Nutr. 2002, 87, S255–S259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madar, Z.; Odes, H.S. Dietary fibre in metabolic diseases. In Dietary Fibre Research; Paoletti, R., Ed.; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 1990; pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- De Man, J.D.; Rogosa, M.; Sharpe, M.E. A medium for the cultivation of Lactobacilli. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1960, 23, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giulio, B.; Orlando, P.; Barba, G.; Coppola, R.; De Rosa, M.; Sada, A.; De Prisco, P.P.; Nazzaro, F. Use of alginate and cryo-protective sugars to improve the viability of lactic acid bacteria after freezing and freeze-drying. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 21, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.F.; Pan, T.M. In Vitro Effects of Lactic Acid Bacteria on Cancer Cell Viability and Antioxidant Activity. J. Food Drug Anal. 2010, 18, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; Coppola, R.; Sada, A.; Orlando, P. Fermentative ability of alginate-prebiotic encapsulated Lactobacillus acidophilus and survival under simulated gastrointestinal conditions. J. Funct. Foods 2009, 1, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar]

- Vulevic, J.; Rastall, R.A.; Gibson, G.R. Developing a quantitative approach for determining the in vitro prebiotic potential of dietary oligosaccharides. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004, 236, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M.; Gutnick, D.; Rosenberg, M. Adherence of bacteria to hydrocarbons: A simple method for measuring cell-surface hydrophobicity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1980, 9, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, H.; Hutkins, R.W. Fermentation of fructooligosaccharides by lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 2682–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meulen, R.; Makras, L.; Verbrugghe, K.; Adriany, T.; De Vuyst, L. In Vitro kinetic analysis of oligofructose consumption by bacteroides and Bifidobacterium spp. indicates different degradation mechanisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 1006–12. [Google Scholar]

- Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; Nicolaus, B.; Poli, A.; Orlando, P. The prebiotic source influences the growth, biochemical features and survival under simulated gastrointestinal conditions of the probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus. Anaerobe 2012. In press (on line from 27th March 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Malago, J.J.; Koninkx, J. F. J. G.; Douma, P. M.; Dirkzwager, A.; Veldmanb, A.; Hendriks, H. G. C. J. M.; van Dijk, J. E. Differential modulation of enterocyte-like Caco-2 cells after exposure to short-chain fatty acids. Food Additiv. Contam. 2003, 20, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberfroid, M.B. Prebiotics and synbiotics: concepts and nutritional properties. Br. J. Nutr. 1998, 80, S197–S202. [Google Scholar]

- Kleerebezem, M.; Boekhorst, J.; van Kranenburg, R.; Molenaar, D.; Kuipers, O.P.; Leer, R.; Tarchini, R.; Peters, S.A.; Sandbrink, H.M.; Fiers, M.W.; et al. Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Proc. Natl .Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 1990–1995. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, F. Host–Flora Interactions in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflam. Bowel Dis. 2004, 10, S16–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Tsao, D.; Siddiqui, B. Effects of sodium butyrate and dimethylsulfoxide on biochemical properties of human colon cancer cells. Cancer 1980, 45, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, A.; Gibson, P.R.; Young, G.P. Butyrate production from dietary fibre and protection against large bowel cancer in a rat model. Gut 1993, 34, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, R.H.; Young, G.P.; Bhathal, P.S. Effects of short chain fatty acids on a new human colon carcinoma cell line (LIM 1215). Gut 1986, 27, 1457–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, G.; Leonarduzzi, G.; Biasi, F.; Chiarpotto, E. Oxidative Stress and Cell Signalling. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004, 11, 1163–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, M.S.; Evans, M.D.; Dizdaroglu, M.; Lunec, J. Oxidative DNA damage: mechanisms, mutation, and diseas. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaizu, H.; Sasaki, M.; Nakajima, H.; Suzuki, Y. Effect of antioxidative lactic acid bacteria on rats fed a diet deficient in vitamin E. J. Dairy Sci. 1993, 76, 2493–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.Y.; Yen, C.L. Antioxidative ability of lactic acid bacteria. J. Agric.. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 1460–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.N.; Yi, X.W.; Yu, H.F.; Dong, B.; Qiao, S.Y. Free radical scavenging activity of Lactobacillus fermentum in vitro and its antioxidative effect on growing–finishing pigs. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 107, 1140–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.Y.; Chang, F.J. Antioxidative effect of intestinal bacteria Bifidobacterium longum ATCC 15708 and Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356. Digest. Dis. Sci. 2000, 45, 1617–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hütt, P.; Shchepetova, J.; Lõivukene, K.; Kullisaar, T.; Mikelsaar., M. Antagonistic activity of probiotic lactobacilli and bifidobacteria against entero- and uropathogens. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 100, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truusalu, K.; Naaber, P.; Kullisaar, T.; Tamm, H.; Mikelsaar, R.H.; Zilmer, K.; et al. The influence of antibacterial and antioxidative probiotic lactobacilli on gut mucosa in a mouse model of Salmonella infection. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2004, 16, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, C.; Bouley, C.; Cayuela, C.; Bouttier, S.; Bourlioux, P.; Bellon-Fontaine, M.N. Cell surface characteristics of Lactobacillus casei subsp. casei, Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei, and Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 1725–1731. [Google Scholar]

- Ouwehand, A.C.; Salminen, S.; Isolauri, E. Probiotics: an overview of beneficial effects. Ant. Van. Leeuw. 2002, 82, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos, B.; Šušković, J.; Vuković, S.; Šimpraga, M.; Frece, J.; Matošić, S. Adhesion and aggregation ability of probiotic strain Lactobacillus acidophilus M92. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 94, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadstrom, T.; Andersson, K.; Sydow, M.; Axelsson, L.; Lindgren, S.; Gullmar, B. Surface properties of lactobacilli isolated from the small intestine of pigs. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1987, 62, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, M.C.; Surono, I.; Meriluoto, J.; Salminen, S. Indigenous dadih lactic acid bacteria: cell-surface properties and interactions with pathogens. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, M89–M93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimoto-Nira, H.; Suzuki, C.; Sasaki, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Mizumachi, K. Survival of a Lactococcus lactis strain varies with its carbohydrate preference under in vitro conditions simulated gastrointestinal tract. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 143, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; Orlando, P.; Coppola, R. Biochemical Traits, Survival and Biological Properties of the Probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum Grown in the Presence of Prebiotic Inulin and Pectin as Energy Source. Pharmaceuticals 2012, 5, 481-492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph5050481

Nazzaro F, Fratianni F, Orlando P, Coppola R. Biochemical Traits, Survival and Biological Properties of the Probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum Grown in the Presence of Prebiotic Inulin and Pectin as Energy Source. Pharmaceuticals. 2012; 5(5):481-492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph5050481

Chicago/Turabian StyleNazzaro, Filomena, Florinda Fratianni, Pierangelo Orlando, and Raffaele Coppola. 2012. "Biochemical Traits, Survival and Biological Properties of the Probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum Grown in the Presence of Prebiotic Inulin and Pectin as Energy Source" Pharmaceuticals 5, no. 5: 481-492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph5050481