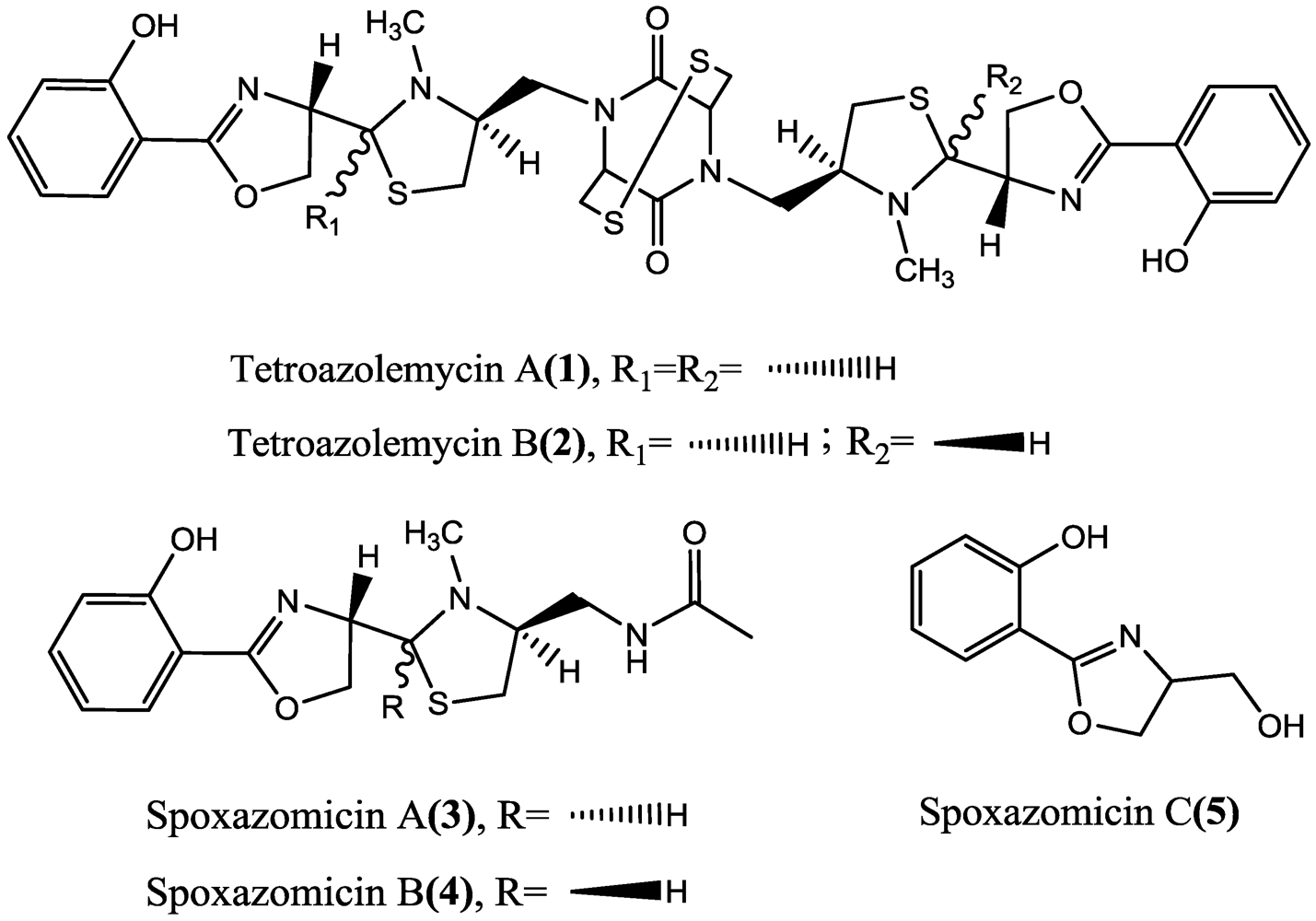

Tetroazolemycins A and B, Two New Oxazole-Thiazole Siderophores from Deep-Sea Streptomyces olivaceus FXJ8.012

Abstract

:1. Introduction

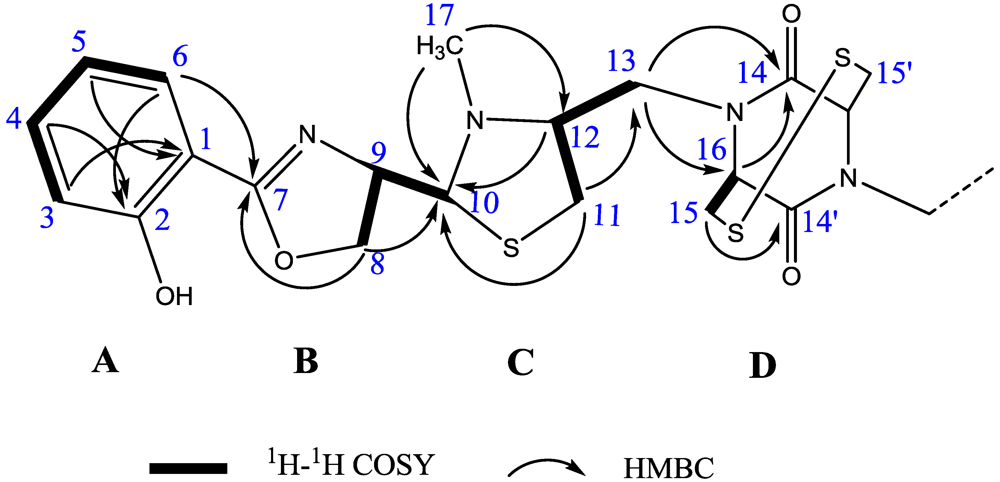

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structural Identification of Tetroazolemycins A and B from Streptomyces olivaceus FXJ8.012

| 1 | 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | δH | δC, mult. | Position | δH | δC, mult. | Position | δH | δC, mult. |

| 1 and 1′ | ― | 110.4, C | 1 | ― | 110.4, C | 1′ | ― | 110.4, C |

| 2 and 2′ | ― | 160.1, C | 2 | ― | 160.0, C | 2′ | ― | 160.0, C |

| 3 and 3′ | 6.97 (d; 7.8) | 116.5, CH | 3 | 6.96 (d; 7.8) | 116.5, CH | 3′ | 6.96 (d; 7.8) | 116.6, CH |

| 4 and 4′ | 7.44 (dd; 7.8, 7.8) | 133.6, CH | 4 | 7.42 (dd; 7.8, 7.8) | 133.7, CH | 4′ | 7.42 (dd; 7.8, 7.8) | 133.7, CH |

| 5 and 5′ | 6.92 (dd; 7.8, 7.8) | 118.6, CH | 5 | 6.91 (dd; 7.8, 7.8) | 118.6, CH | 5′ | 6.91 (dd; 7.8, 7.8) | 118.7, CH |

| 6 and 6′ | 7.67 (d; 7.8) | 128, CH | 6 | 7.65 (d; 7.8) | 128.0, CH | 6′ | 7.63 (d; 7.8) | 128.0, CH |

| 7 and 7′ | ― | 166.2, C=N | 7 | ― | 166.2, C=N | 7′ | ― | 166.2, C=N |

| 8 and 8′-a | 4.47 (m) | 69.8, CH2 | 8-a | 4.46 (m) | 69.9, CH2 | 8′-a | 4.29 (m) | 69.3, CH2 |

| 8 and 8′-b | 4.62 (m) | 8-b | 4.62 (m) | 8′-b | 4.53 (dd; 8.4, 9.6) | |||

| 9 and 9′ | 4.62 (m) | 71.4, CH | 9 | 4.61 (m) | 71.2, CH | 9′ | 4.77 (m) | 67.9, CH |

| 10 and 10′ | 4.24 (d; 6.0) | 78.5, CH | 10 | 4.22 (d; 6.6) | 78.6, CH | 10′ | 4.62 (m) | 77.1, CH |

| 11 and 11′-a | 2.90 (dd; 6.6, 11.4) | 34.2, CH2 | 11-a | 2.90 (m) | 34.2, CH2 | 11′-a | 2.77 (m) | 32.6, CH2 |

| 11 and 11′-b | 3.15 (dd; 6.6, 11.4) | 11-b | 3.18 (m) | 11′-b | 3.00 (m) | |||

| 12 and 12′ | 3.49 (m) | 70.4, CH | 12 | 3.49 (m) | 70.3, CH | 12′ | 3.84 (m) | 67.0, CH |

| 13 and 13′-a | 2.92 (dd; 7.2, 13.8) | 47.4, CH2 | 13-a | 2.90 (m) | 47.5, CH2 | 13′-a | 3.13 (m) | 42.6, CH2 |

| 13 and 13′-b | 4.05 (dd; 6.6, 13.8) | 13-b | 4.03 (m) | 13′-b | 4.05 (m) | |||

| 14 and 14′ | ― | 168.8, C=O | 14 | ― | 168.9, C=O | 14′ | ― | 169.3, C=O |

| 15 and 15′ | 3.65 (d; 3.6) | 45.4, CH2 | 15 | 3.64 (m) | 45.4, CH2 | 15′ | 3.62 (m) | 45.6, CH2 |

| 16 and 16′ | 4.75 (t; 3.8) | 60.1, CH | 16 | 4.78 (m) | 60.2, CH | 16′ | 4.75 (m) | 59.4, CH |

| 17 and 17′ | 2.52 (s) | 44.2, CH3 | 17 | 2.54 (s) | 44.4, CH3 | 17′ | 2.45 (s) | 36.2, CH3 |

2.2. The Activities of Compounds 1 and 2

2.3. Discussion

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General

3.2. Actinomycete Strain

3.3. Fermentation, Extraction and Isolation

3.4. Metal Ion Binding Assay

3.5. Bioactivity Assay

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References and Notes

- Baltz, R.H. Antimicrobials from actinomycetes: Back to the future. Microbe 2007, 2, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Bérdy, J. Bioactive microbial metabolites. J. Antibiot. 2005, 58, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.K. Discovery of novel metabolites from marine actinomycetes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006, 9, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.X.; An, R.; Wang, J.P.; Sun, N.; Zhang, S.; Hu, J.C.; Kuai, J. Exploring novel bioactive compounds from marine microbes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2005, 8, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunt, J.W.; Copp, B.R.; Hu, W.P.; Munro, M.H.G.; Northcote, P.T.; Prinsep, M.R. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008, 25, 35–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunt, J.W.; Copp, B.R.; Hu, W.P.; Munro, M.H.G.; Northcote, P.T.; Prinsep, M.R. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009, 26, 170–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugni, T.S.; Ireland, C.M. Marine-derived fungi: A chemically and biologically diverse group of microorganisms. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004, 21, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Ali, M.S.; Hussain, S.; Jabbar, A.; Ashraf, M.; Lee, Y.S. Marine natural products of fungal origin. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007, 24, 1142–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GYM-agar (1000 mL): yeast extract (4 g, Oxoid), malt extract (4 g, Bacto), glucose (10 g), CaCO3 (2 g) and agar (15 g).

- Boukhalfa, H.; Crumbliss, A.L. Chemical aspects of siderophore mediated iron transport. BioMetals 2002, 15, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dictionary of Natural Products on DVD; Chapman & Hall Ltd.: London, UK, 2010.

- Inahashi, Y.; Iwatsuki, M.; Ishiyama, A.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara-Tsukashima, A.; Matsumoto, A.; Hirose, T.; Sunazuka, T.; Yamada, H.; Otoguro, K.; et al. Spoxazomicins A–C, novel antitrypanosomal alkaloids produced by an endophytic actinomycete, Streptosporangium oxazolinicum K07–0460T. J. Antibiot. 2011, 64, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinehart, K.L.; Staley, A.L.; Wilson, S.R.; Ankenbauer, R.G.; Cox, C.D. Stereochemical assignment of the pyochelins. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 2786–2791. [Google Scholar]

- Shindo, K.; Takenaka, A.; Noguchi, T.; Hayakawa, Y.; Seto, H. Thiazostatin A and thiazostatin B, new antioxidants produced by Streptomyces tolurosus. J. Antibiot. 1989, 42, 1526–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Igarashi, Y.; Saito, N.; Furumai, T. Watasemycins A and B, new antibiotics produced by Streptomyces sp. TP-A0597. J. Antibiot. 2002, 55, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, Y.; Mukai, A.; Yazawa, K.; Uno, J.; Ando, A.; Mikami, Y.; Fukai, T.; Ishikawa, J.; Yamaguchi, K. Transvalencin Z, a new antimicrobial compound with salicylic acid residue from Nocardia transvalensis IFM 10065. J. Antibiot. 2004, 57, 803–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakouti, I.; Hobbs, G. A New approach to studying ion uptake by actinomycetes. J. Basic Microbiol. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallifidas, D.; Pascoe, B.; Owen, G.A.; Strain-Damerell, C.M.; Hong, H.J.; Paget, M.S. The zinc-responsive regulator Zur controls expression of the coelibactin gene cluster in Streptomyces coelicolor. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 608–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Wang, H.B.; Liu, M.; Gu, Q.; Zheng, W.; Huang, Y. Streptomyces alni sp. nov., a daidzein-producing endophyte isolated from a root of Alnus nepalensis D. Don. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, N.; Xi, L.J.; Rong, X.Y.; Ruan, J.S.; Huang, Y. Genetic screening strategy for rapid access to polyether ionophore producers and products in actinomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 3433–3442. [Google Scholar]

- LB agar (1000 mL): tryptone (10 g, Bacto), yeast extract (5 g, Bacto), NaCl (10 g), and agar (15 g).

- PDA agar (1000 mL): fresh potato (200 g), glucose (20 g) and agar (15 g). Boil fresh potato for 20–30 min, and filter the juices with multi-layer gauzes. Use filtered juices to make PDA-agar medium.

- Shapiro, S.; Meier, A.; Guggenheim, B. The antimicrobial activity of essential oils and essential oil components toward oral bacteria. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 1994, 9, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, S.C.; Lu, X.H.; Guo, L.D.; Zhang, H.; Che, Y.S. Allenyl and alkynyl phenyl ethers from the endolichenic fungus Neurospora terricola. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 1782–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Supplementary Files

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, N.; Shang, F.; Xi, L.; Huang, Y. Tetroazolemycins A and B, Two New Oxazole-Thiazole Siderophores from Deep-Sea Streptomyces olivaceus FXJ8.012. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 1524-1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/md11051524

Liu N, Shang F, Xi L, Huang Y. Tetroazolemycins A and B, Two New Oxazole-Thiazole Siderophores from Deep-Sea Streptomyces olivaceus FXJ8.012. Marine Drugs. 2013; 11(5):1524-1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/md11051524

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ning, Fei Shang, Lijun Xi, and Ying Huang. 2013. "Tetroazolemycins A and B, Two New Oxazole-Thiazole Siderophores from Deep-Sea Streptomyces olivaceus FXJ8.012" Marine Drugs 11, no. 5: 1524-1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/md11051524