A Review of Programs That Targeted Environmental Determinants of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Identifying and Characterising Program Targets

3. Results

3.1. Literature Review

3.1.1. Programs Identified in Peer-Reviewed Research Journals

| Program name | Activity | Targets | Target levels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporary Reversion to Traditional Lifestyle (Kimberley, WA, Australia) [21] 1984 * | • Returning to traditional lands | Community members | IND, COM |

| • Hunting/Gathering | Community members | IND, COM | |

| Minjilang Health Program (Top End, NT, Australia) [22,23] 1994, 1995 | • Provide and promote nutritious food in store | Food supply | IND, ORG, INT, COM |

| • Regular air charter to transport fresh produce | Food supply | ORG, COM | |

| • ALPA store nutrition policy ** | Food supply | ORG, COM | |

| • Elders told traditional stories highlighting overconsumption and greed and community interpreted these as warnings about overconsumption of fat and sugar. | Community members | IND, INT | |

| • “Shelf-talkers” to highlight target foods | Shoppers; store characteristics | IND, ORG, INT | |

| • Alcohol prohibition | Minjilang community | COM, INT | |

| • Heart health screening program | Clinical systems | ORG, IND, COM | |

| Eliminating petrol sniffing (Arnhem Land, NT, Australia) [24] 1995 | • Introduction of Avgas in Maningrida | Fuel supply | ORG, COM |

| • Community support and governance | Community capacity | COM | |

| • Employment and skills-training programs | Community capacity | IND | |

| Halls Creek Alcohol Program (Halls Creek, WA, Australia) [25] 1998 | • No packaged liquor sold before midday | Hotel/Bottle shops | ORG, SOC |

| • Cask wine only sold between 4 pm and 6 pm | Hotel/Bottle shops | ORG, SOC | |

| • One case of wine per person on any one day | Customer | IND, COM | |

| • School education program | Students | IND, COM | |

| • Introduction of CDEP | unemployed | IND, COM | |

| • Expanded TAFE services | Education system | COM, SOC | |

| • Arts centre established | Community infrastructure | COM | |

| Looma Healthy Lifestyle (Kimberley, WA, Australia) [26,27] 2000, 2001 | • Store management policy changes | Food supply | ORG |

| • Formal and informal education sessions | Community members | IND, INT | |

| • Regular exercise groups | Community members | IND, INT | |

| • Simple dietary advice | Community members | IND | |

| • Sports festivals | Community members & orgs | IND, INT, ORG | |

| • Art competitions and sporting festivals | Community members & orgs | IND, INT, ORG | |

| • nonsmoking policy in public buildings | Public building space | COM, IND | |

| • Store tours to identify healthy food choices. | Shoppers | IND | |

| • Hunting trips, sport, walking groups | Community members, teams/groups | IND, INT, COM | |

| • Sport and recreational officer appointed | Organisational capacity | ORG | |

| • Council set up office as a base for program | Program infrastructure | ORG | |

| • Health education classes conducted by AHWs in the community school | Students | IND | |

| • School curriculum change | School | ORG | |

| Nutrition awareness and healthy lifestyle program (Central Australia, NT, Australia) [28] 2000 | • Changes to food supply at the community store | Food supply | ORG |

| • Nutrition awareness | Community members | IND | |

| Waste water-reuse Program (13 remote communities, WA, Australia) [29] 2001 | • Evapotranspiration units installed in 13 communities | Waste management infrastructure | COM |

| Review of petrol sniffing programs (Aboriginal communities across Australia) [30] 2002 | • Substitution of petrol with Avgas/Comgas | Fuel supply | ORG |

| • Using unleaded petrol | Fuel supply | ORG | |

| • Locking up petrol supplies | Fuel supply | ORG | |

| • Adding deterrents to petrol | Fuel supply | ORG | |

| • Movement to outstations/homeland centres | Community members | IND, INT | |

| Remote community swimming pools (Mugarinya & Jigalong, WA, Australia) [31,32] 2003, 2008 | • Installation of a swimming pool | Community infrastructure | COM |

| • “No School-No Pool” policy | School | ORG, SOC | |

| Clinical Systems Development; ABCD (Top End, NT, Australia) [33,34,35] 2004, 2007 | • Clinical guidelines | Clinical practice | ORG |

| • Electronic systems to support implementation of clinical guidelines | Clinical practice | ORG | |

| • Staff training | Clinical capacity | ORG | |

| Community tobacco study (Top End, NT, Australia) [36] 2006 | • Smoke-free enclosed public places | Public places | ORG, COM, IND |

| • Sports carnival sponsorship | Community members and Orgs | ORG | |

| • Culturally appropriate health promotion materials | Community members | IND | |

| • Women’s Centre tobacco education program | Women | IND | |

| • School education about tobacco | Students | IND | |

| Mt Theo Program (Central Australia, NT, Australia) [37] 2006 | • Placement at Outstation | Community members | IND |

| • Discussion with Elders | Community members | IND, INT | |

| • Hunting | Community members | IND, INT | |

| • Love, care and pray for young people | Young people | IND | |

| • Education and healthcare | Community members | IND | |

| • Diversion program | Community members | IND | |

| Alcohol Restrictions Trial (Alice Springs, NT, Australia) [38] 2006 | • Ban on alcohol in containers >2 L | Alcohol supply | ORG, COM |

| • Reduced take-away trading hours | Store | ORG, SOC | |

| • Only light beer sold in bars before noon | Hotels | ORG, SOC | |

| Health Hardware Program (132 communities, TSI, NT, NSW, WA, QLD, NSW, SA, Australia) [39] 2008 | • Development of survey-fix methods | Healthhabitat’s intellectual property | ORG, SOC |

| • Local members recruited and trained | Community members & capacity | IND, COM | |

| • Survey fix process | Houses in community | COM | |

| • Fixing hardware | Family homes | INT, COM | |

| Caring for Country (Arnhem Land, NT, Australia) [40] 2008 | • Time on country | Land and people | IND, COM |

| • Burning of annual grasses | Land | IND, COM | |

| • Using country; gathering food & medicinal resources | Land and people | IND, COM | |

| • Ceremony | Land and people | IND, COM | |

| • Protecting country/sacred areas | Land and people | IND, COM | |

| • Producing artwork | People | IND, COM | |

| Homelands Movement (Central Australia, NT, Australia) [41,42] 2008, 2012 | • Land Rights Act passed | Commonwealth Legislation | SOC |

| • Return of Clans to traditional lands | Community members | INT, COM, IND | |

| • Establishment of outstations | Community infrastructure | COM | |

| • Administrative offices established | Community infrastructure | ORG, COM, SOC | |

| • Store established | Supplies | ORG, COM, SOC | |

| • Clinic established | Urapuntja Health Service | ORG, IND, COM | |

| • Outreach Health Service | Community members on Homelands | COM, IND, INT, ORG | |

| • Alcohol prohibition | Utopia community | COM | |

| Northern Territory Emergency Response (10 remote communities, NT, Australia) [43] 2010 | • 50% Income Management by Government | Aboriginal people on Social Security payments in 73 prescribed communities | IND, INT, COM |

| • Racial Discrimination Act suspended | Commonwealth legislation | SOC | |

| Health Promotion Program (Goulburn-Murray Region, VIC, Australia) [44] 2011 | • Healthy canteen policy | Food supply | IND, ORG |

| • Health Summer School | Health promotion practitioners | IND, ORG | |

| • “Hungry for Victory” youth nutrition program | U17 footballers & netballers; mentors | IND, INT, ORG | |

| • Provision of fruit for members | RFNC attendees, club members | IND, ORG | |

| • Focus groups on guidelines | Participants; organisational partnership | IND, ORG | |

| • Women’s Wellbeing Group | Women; organisational partnership | IND, ORG | |

| • 10-week body challenge | Workplace; staff members | IND, ORG | |

| Healthy Lifestyle Program (Arnhemland, NT, Australia) [16] 2011 | • School canteen with good facilities, nutritious snacks | Food supply | ORG, IND |

| • Community marke—access to fresh fruits, bush foods, fish and shell-fish | Food supply | COM | |

| • Restrictions on deep-fried food sales | Store | ORG, COM | |

| • Healthy breakfast program at school | Students | IND, INT, ORG | |

| • Family food gardens | Families | INT, IND | |

| • Community footy league established | Young men | IND, COM | |

| • Healthy Lifestyle Festival | Community members | IND, INT, ORG, COM | |

| • Weekly walking program | Community members | IND, INT | |

| Cape York SRS (Cape York, QLD, Australia) [45] 2011 | • Govt regulated legal availability of alcohol for sale, in partnership with Elders and locals | Law | SOC |

| • Individual possession limits | Community member | IND | |

| • Police and judicial enforcement | Community member | IND | |

| Housing Program (10 communities, NT, Australia) [46] 2011 | • Construction of new houses | Housing infrastructure | COM, SOC |

| • Uninhabitable houses earmarked for demolition | Housing infrastructure | COM, SOC | |

| Bush food harvesting (central Australia, NT, Australia) [47] 2011 | • Burning | Land | IND, COM |

| • Ceremony | Land and people | IND, COM | |

| • Protecting country/sacred areas | Land and people | IND, COM | |

| • Family harvesting trips | Land and people | IND, INT, COM | |

| • Processing and selling plant produce | Produce, people, family, community | IND, COM | |

| Arafura Rangers (Arnhemland, NT, Australia) [48] 2012 | • Burning | Land | IND, COM |

| • Protecting country/sacred areas | Land and people | IND, COM | |

| • Training in aquaculture | Workforce capacity | IND, COM | |

| • Recording Traditional Ecological Knowledge | unclear from description | ||

| Wunambal Gaambera Healthy Country Project (Kimberley, WA, Australia) [49] 2012 | • Time on country | Land and people | IND, COM |

| • Burning | Land | IND, COM | |

| • Using country | Land and people | IND, COM | |

| • Protecting Country/sacred areas | Land and people | IND, COM | |

| • Producing artwork | People | IND, COM | |

| • Native Title application | Legal recognition by mainstream | SOC | |

| • Developing partnerships with government and NGOs | WGHC Project | ORG |

| Program aims | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition | Physical activity | Social | Caring for Country | Preventing substance misuse | Clinical management | Health hardware |

| Society and/or community level targets | ||||||

| National policy | Local policy | National and local policy | National policy | National and local policy | ||

| Infrastructure | Infrastructure | Infrastructure | Landscape | Infrastructure | Infrastructure | Infrastructure |

| Homelands living | Homelands living | Homelands living | Homelands living | Homelands living | Homelands living | |

| Community and/or organisation level targets | ||||||

| Food supply | Food supply | Food supply | Supply restriction | |||

| Transportation | Clinical systems | Clinical systems | ||||

| Organisational partnerships | Organisational partnerships | Organisational partnerships | Organisational partnerships | Organisational partnerships | ||

| Workforce | Workforce | Workforce | Workforce | Workforce | Workforce | |

| capacity | capacity | capacity | capacity | capacity | capacity | |

| Interpersonal and/or individual level targets | ||||||

| Opportunities for exercise | Opportunities for exercis | Opportunities for exercis | Opportunities for exercis | |||

| Social connectedness | Social connectedness | Social connectedness | Social connectedness | Social connectedness | ||

| Diversion of spending | Generating income | Diversion of spending | ||||

| Knowledge & education | Knowledge & education | Knowledge & education | Knowledge & education | Knowledge & education | Knowledge & education | Knowledge & education |

3.1.2. Nutrition

3.1.3. Physical Activity

3.1.4. Social Programs

3.1.5. Caring for Country

3.1.6. Preventing Substance Misuse

3.1.7. Clinical Management of Chronic Disease

3.1.8. Health Hardware

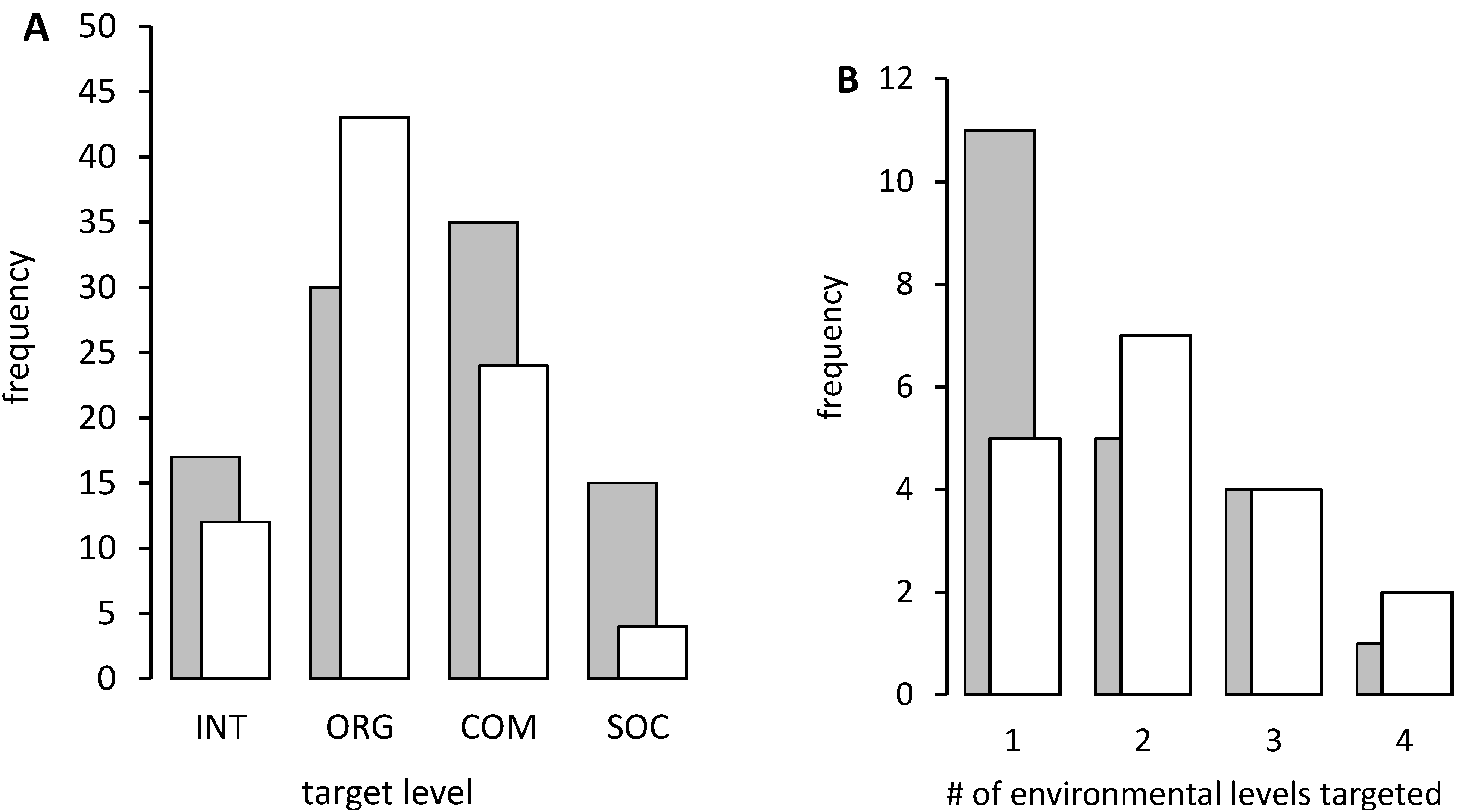

3.2. Characterising Types of Environmental Targets and Their Frequency

3.2.1. Levels at Which Program Targets Were Located—Western and Indigenous Perspectives

3.2.2. Targetting Multiple Environmental Levels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Rayner, G. Conventional and ecological public health. Public Health 2009, 123, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panter-Brick, C.; Clarke, S.E.; Lomas, H.; Pinder, M.; Lindsay, S.W. Culturally compelling strategies for behaviour change: A social ecology model and case study in malaria prevention. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 2810–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, L.; Potvin, L.; Kishchuk, N.; Prlic, H.; Green, L.W. Assessment of the integration of the ecological approach in health promotion programs. Am. J. Health Promot. 1996, 10, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trickett, E.J.; Mitchell, R.E. An ecological metaphor for research and intervention in community psychology. In Community psychology: Theoretical and Empirical Approaches, 2nd ed.; Gibbs, M.S., Lachenmeyer, J.R., Sigal, J., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kok, G.; Gottlieb, N.H.; Commers, M.; Smerecnik, C. The ecological approach in health promotion programs: A decade later. Am. J. Health Promot. 2008, 22, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.G. Living Systems; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party, A National Aboriginal Health Strategy: Report of the National Health Strategy Working Party; Commonwealth Department of Aboriginal Affairs: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 1989.

- Marmot, M. Social determinants and the health of Indigenous Australians. Med. J. Aust. 2011, 194, 512–513. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health, The Health and Wellbeing of Aboriginal Victorians: Victorian Population Health Survey 2008 Supplementary Report; Department of Health: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2011.

- Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, Overcoming Indigenous Disadvanatge: Key Indicators; Productivity Commission: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2011.

- National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health: Framework for Action by Governments; National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Council: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2003.

- Calma, T.; Dick, D. Social Determinants and The Health of Indigenous Peoples in Australia—A Human Rights Based Approach; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Calma, T. A human rights based approach to social and emotional wellbeing. Australas. Psychiatr. 2009, 17, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Criteria for Health and Medical Research of Indigenous Australians. Available online: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/grants/indighth.pdf (accessed 17 July 2013).

- Cook, K.E. Using critical ethnography to explore issues in health promotion. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargo, M.; Marks, E.; Brimblecombe, J.; Scarlett, M.; Maypilama, E.; Dhurrkay, J.G.; Daniel, M. Integrating an ecological approach into an Aboriginal community-based chronic disease prevention program: A longitudinal process evaluation. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, L.; Gauvin, L.; Potvin, L.; Denis, J.L.; Kishchuk, N. Making youth tobacco control programs more ecological: Organizational and professional profiles. Am. J. Health Promot. 2002, 16, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, L.; Guilbault, G.; Delormier, T.; Potvin, L. Unpacking the black box: A deconstruction of the programming approach and physical activity interventions implemented in the Kahnawake schools diabetes prevention project. Health Promot. Pract. 2005, 6, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, F. Aboriginal recommendations for substance use program evaluation. Aborig. Isl. Health Work. J. 2010, 34, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rigney, L.I. Internationalization of an Indigenous anticolonial cultural critique of research methodologies: A guide to indigenist research methodology and its principles. Wicazo Sa Rev. 1997, 14, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, K. Marked improvement in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in diabetic Australian Aborigines after temporary reversion to traditional lifestyle. Diabetes 1984, 33, 596–603. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.J.; Bonson, A.P.; Yarmirr, D.; O’Dea, K.; Mathews, J.D. Sustainability of a successful health and nutrition program in a remote Aboriginal community. Med. J. Aust. 1995, 162, 632–635. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.J.; Bailey, A.P.; Yarmirr, D.; O’Dea, K.; Mathews, J.D. Survival tucker: Improved diet and health indicators in an Aboriginal community. Aust. J. Public Health 1994, 18, 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, C.B.; Currie, B.J.; Clough, A.B.; Wuridjal, R. Evaluation of strategies used by a remote Aboriginal community to eliminate petrol sniffing. Med. J. Aust. 1995, 163, 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M. Restriction of the hours of sale of alcohol in a small community: A beneficial impact. Aust. NZ J. Public Health 1998, 22, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, K.G.; Daniel, M.; Skinner, K.; Skinner, M.; White, G.A.; O’Dea, K. Effectiveness of a community-directed “healthy lifestyle” program in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. Aust. NZ J. Public Health 2000, 24, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, K.G.; Su, Q.; Cincotta, M.; Skinner, M.; Skinner, K.; Pindan, B.; White, G.A.; O’Dea, K. Improvements in circulating cholesterol, antioxidants, and homocysteine after dietary intervention in an Australian Aboriginal community. Am. J. Clin Nutr. 2001, 74, 442–448. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, R.; Rowley, K.G.; Lee, A.J.; Knight, S.; O’Dea, K. Increase in prevalence of obesity and diabetes and decrease in plasma cholesterol in a central Australian Aboriginal community. Med. J. Aust. 2000, 172, 480–484. [Google Scholar]

- Anda, M.; Mathew, K.; Ho, G. Evapotranspiration for domestic wastewater reuse in remote Indigenous communities of Australia. Water Sci. Technol. 2001, 44, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- MacLean, S.J.; D’Abbs, P.H. Petrol sniffing in Aboriginal communities: A review of interventions. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2002, 21, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, D.; Tennant, M.T.; Silva, D.T.; McAullay, D.; Lannigan, F.; Coates, H.; Stanley, F.J. Benefits of swimming pools in two remote Aboriginal communities in Western Australia: Intervention study. BMJ 2003, 327, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.T.; Lehmann, D.; Tennant, M.T.; Jacoby, P.; Wright, H.; Stanley, F.J. Effect of swimming pools on antibiotic use and clinic attendance for infections in two Aboriginal communities in Western Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2008, 188, 594–598. [Google Scholar]

- Bailie, R.; Si, D.; Dowden, M.; O’Donoghue, L.; Connors, C.; Robinson, G.; Cunningham, J.; Weeramanthri, T. Improving organisational systems for diabetes care in Australian Indigenous communities. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2007, 7, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailie, R.S.; Si, D.; Robinson, G.W.; Togni, S.J.; D’Abbs, P.H. A multifaceted health-service intervention in remote Aboriginal communities: 3-year follow-up of the impact on diabetes care. Med. J. Aust. 2004, 181, 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Si, D.; Bailie, R.S.; Dowden, M.; O’Donoghue, L.; Connors, C.; Robinson, G.W.; Cunningham, J.; Condon, J.R.; Weeramanthri, T.S. Delivery of preventive health services to Indigenous adults: Response to a systems-oriented primary care quality improvement intervention. Med. J. Aust. 2007, 187, 453–457. [Google Scholar]

- Ivers, R.G.; Castro, A.; Parfitt, D.; Bailie, R.S.; D’Abbs, P.H.; Richmond, R.L. Evaluation of a multi-component community tobacco intervention in three remote Australian Aboriginal communities. Aust. NZ J. Public Health 2006, 30, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, K.; Brown, J.N. Stopping petrol sniffing in remote Aboriginal Australia: Key elements of the Mt Theo program. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006, 25, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, E.; Boffa, J.; Rosewarne, C.; Bell, S.; Chee, D.A. What price do we pay to prevent alcohol-related harms in Aboriginal communities? The Alice Springs trial of liquor licensing restrictions. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006, 25, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torzillo, P.J.; Pholeros, P.; Rainow, S.; Barker, G.; Sowerbutts, T.; Short, T.; Irvine, A. The state of health hardware in Aboriginal communities in rural and remote Australia. Aust. NZ J. Public Health 2008, 32, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, C.P.; Berry, H.L.; Gunthorpe, W.; Bailie, R.S. Development and preliminary validation of the “Caring for Country” questionnaire: Measurement of an Indigenous Australian health determinant. Int. J. Equity Health 2008, 7, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, K.G.; O’Dea, K.; Anderson, I.; McDermott, R.; Saraswati, K.; Tilmouth, R.; Roberts, I.; Fitz, J.; Wang, Z.; Jenkins, A.; et al. Lower than expected morbidity and mortality for an Australian Aboriginal population: 10-year follow-up in a decentralised community. Med. J. Aust. 2008, 188, 283–287. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, H.; Kowal, E. Culture, history, and health in an Australian Aboriginal community: The case of Utopia. Med. Anthr. 2012, 31, 438–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimblecombe, J.K.; McDonnell, J.; Barnes, A.; Dhurrkay, J.G.; Thomas, D.P.; Bailie, R.S. Impact of income management on store sales in the Northern Territory. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 192, 549–554. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, R.E.; Cincotta, M.; Doyle, J.; Firebrace, B.R.; Cargo, M.; van den Tol, G.; Morgan-Bulled, D.; Rowley, K.G. A pilot study of Aboriginal health promotion from an ecological perspective. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, S.A.; Ypinazar, V.A.; Muller, R.; Clough, A. Increasing alcohol restrictions and rates of serious injury in four remote Australian Indigenous communities. Med. J. Aust. 2011, 194, 503–506. [Google Scholar]

- Bailie, R.S.; McDonald, E.L.; Stevens, M.; Guthridge, S.; Brewster, D.R. Evaluation of an Australian Indigenous housing programme: Community level impact on crowding, infrastructure function and hygiene. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2011, 65, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F.; Douglas, J. No bush foods without people: The essential human dimension to the sustainability of trade in native plant products from desert Australia. Rangel. J. 2011, 33, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, N.; Bramley, C.; Bar-Lev, J.; Guyula, M.; O’Ryan, S. Arafura three: Aboriginal ranger groups protecting and managing an internationally significant swamp. Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2012, 13, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorcroft, H.; Ignjic, E.; Cowell, S.; Goonack, J.; Mangolomara, S.; Oobagooma, J.; Karadada, R.; Williams, D.; Waina, N. Conservation planning in a crosscultural context: The Wunambal Gaambera healthy Country project in the Kimberley, Western Australia. Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2012, 13, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, K.G.; Lee, A.J.; Yarmirr, D.; O’Dea, K. Homocysteine concentrations lowered following dietary intervention in an Aboriginal community. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 12, 92–95. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, P.; Duncan, M.; Gray, B. Review of The NTER Review Board; Commowealth of Australia: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Lifesaving Society—Australia Royal Lifesaving in Indigenous Communities. Available online: http://www.royallifesaving.com.au/www/html/516-indigenous-programs.asp (accessed on 5 April 2013).

- D’Abbs, P.H.; MacLean, S.J.; Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal and Tropical Health (Australia). Petrol Sniffing in Aboriginal Communities: A Review of Interventions; Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal and Tropical Health: Darwin, NT, Australia, 2000; p. 98. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, C.P.; Johnston, F.H.; Berry, H.L.; McDonnell, J.; Yibarbuk, D.; Gunabarra, C.; Mileran, A.; Bailie, R.S. Healthy country, healthy people: The relationship between Indigenous health status and “Caring for Country”. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 190, 567–572. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Indigenous Protected Areas. Available online: http://www.environment.gov.au/indigenous/ipa/index.html (accessed on 17 July 2013).

- McDermott, R.; O’Dea, K.; Rowley, K.; Knight, S.; Burgess, P. Beneficial impact of the homelands movement on health outcomes in Central Australian Aborigines. Aust. NZ J. Public Health 1998, 22, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langton, M. Urbanizing Aborigines, the social scientists’ great deception. Soc. Altern. 1981, 2, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Brough, M. Healthy imaginations: A social history of the epidemiology of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Med. Anthropol. 2001, 20, 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, R.; Doyle, J.; Bretherton, D.; Rowley, K. Identifying psychosocial mediators of health amongst Indigenous Australians for the Heart Health Project. Ethn. Health 2008, 13, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; Gifford, S.; Thorpe, L. The social and cultural context of risk and prevention: Food and physical activity in an urban Aboriginal community. Health Educ. Behav. 2000, 27, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickery, J.; Faulkhead, S.; Adams, K.; Clarke, A. Indigenous insights into oral history, social determinants and decolonisation. In Beyond Bandaids: Exploring the Underlying Social Determinants of Aboriginal Health; Anderson, I., Baum, F., Bentley, M., Eds.; Co-Operative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health: Darwin, NT, Australia, 2007; Chapter 2; pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Prober, S.M.; O’Connor, M.; Walsh, F. Australian Aboriginal peoples’ seasonal knowledge: A potential basis for shared understanding in environmental management. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, C.P.; Johnston, F.H.; Bowman, D.M.; Whitehead, P.J. Healthy country: Healthy people? Exploring the health benefits of Indigenous natural resource management. Aust. NZ J. Public Health 2005, 29, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D. Application of an integrated multidisciplinary economic welfare approach to improved wellbeing through Aboriginal Caring for Country. Rangel. J. 2011, 33, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailovich, K.; Morrison, P.; Arabena, K. Evaluating Australian Indigenous community health promotion initiatives: A selective review. Rural Remote Health 2007, 7, 746–764. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, L.; Gauvin, L.; Raine, K. Ecological models revisited: Their uses and evolution in health promotion over two decades. Ann. Rev. Public Health 2010, 32, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.J.; Leonard, D.; Moloney, A.A.; Minniecon, D.L. Improving Aboriginal and Torres strait islander nutrition and health. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 190, 547–548. [Google Scholar]

- Brimblecombe, J.K.; O’Dea, K. The role of energy cost in food choices for an Aboriginal population in Northern Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 190, 549–551. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, E.; Bailie, R.; Grace, J.; Brewster, D. An ecological approach to health promotion in remote Australian Aboriginal communities. Health Promot. Int. 2010, 25, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Johnston, L.; Doyle, J.; Morgan, B.; Atkinson-Briggs, S.; Firebrace, B.; Marika, M.; Reilly, R.; Cargo, M.; Riley, T.; Rowley, K. A Review of Programs That Targeted Environmental Determinants of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 3518-3542. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10083518

Johnston L, Doyle J, Morgan B, Atkinson-Briggs S, Firebrace B, Marika M, Reilly R, Cargo M, Riley T, Rowley K. A Review of Programs That Targeted Environmental Determinants of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2013; 10(8):3518-3542. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10083518

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohnston, Leah, Joyce Doyle, Bec Morgan, Sharon Atkinson-Briggs, Bradley Firebrace, Mayatili Marika, Rachel Reilly, Margaret Cargo, Therese Riley, and Kevin Rowley. 2013. "A Review of Programs That Targeted Environmental Determinants of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10, no. 8: 3518-3542. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10083518