Smoke-Free Laws and Direct Democracy Initiatives on Smoking Bans in Germany: A Systematic Review and Quantitative Assessment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Federal Non-smokers Protection

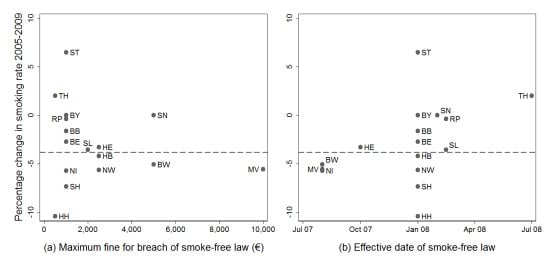

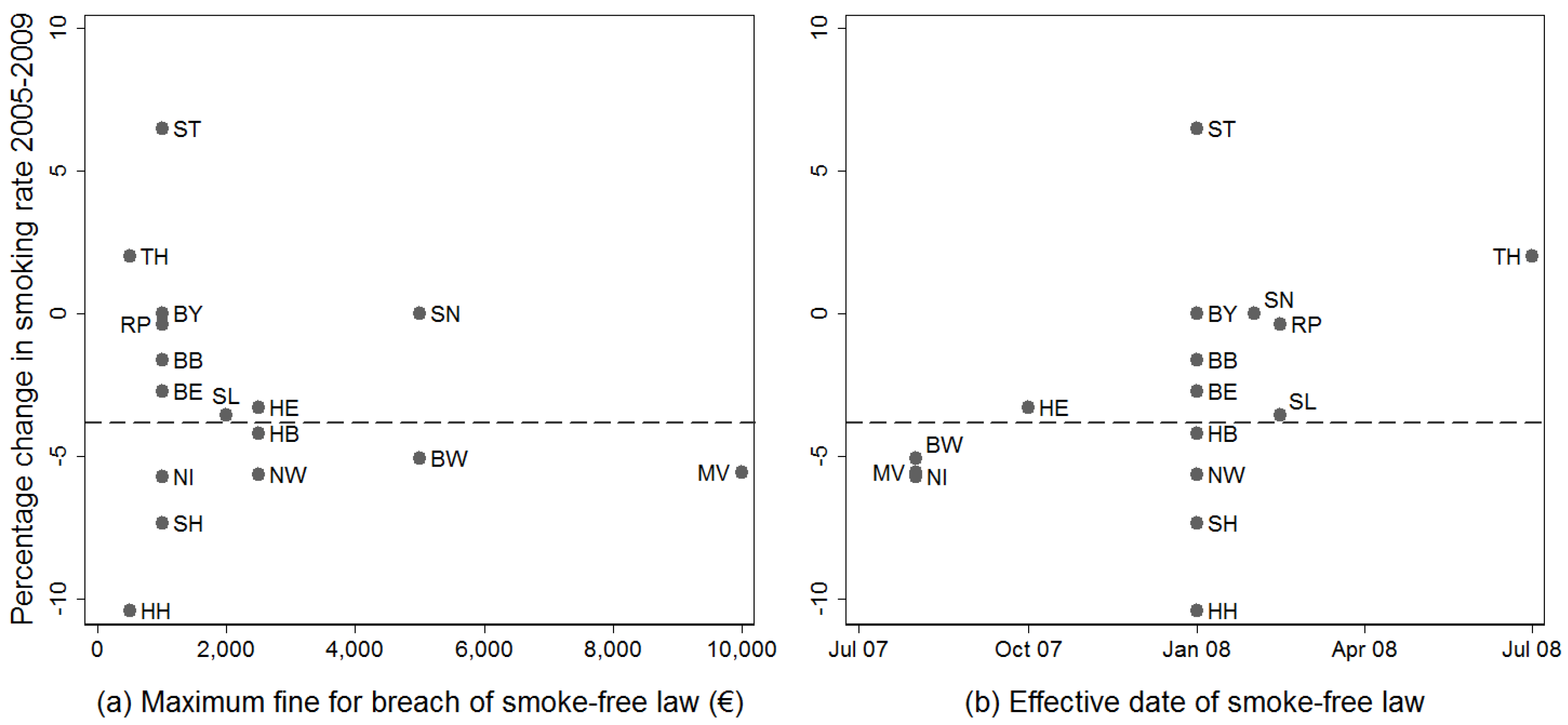

| Federal State | Code | Effective Date | Changes | Expiry Date | Fine (€) | Pubs and Restaurants | Smoking Rate 2009 | % Change since 2005 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Last | # | ||||||||

| Baden-Wuerttemberg | BW | 01.08.07 | 03.03.09 | 1 | None | ≤40/2,500 | Ban a,b | 24.4 | −5.1 |

| Bavaria | BY | 01.01.08 | 23.07.10 | 3 | None | (5–1,000) | Ban c | 25.6 | 0.0 |

| Berlin | BE | 01.01.08 | 03.06.10 | 3 | None | ≤100/1,000 | Ban a,b,d | 32.1 | −2.7 |

| Brandenburg | BB | 01.01.08 | 15.07.10 | 2 | None | 5–100/10–1,000 | Ban a,b | 30.7 | −1.6 |

| Bremen | HB | 01.01.08 | 25.06.13 | 4 | 31.07.18 | ≤500/2,500 | Ban a,b | 32.1 | −4.2 |

| Hamburg | HH | 01.01.08 | 19.06.12 | 3 | None | 20–200/50–500 | Ban a,b | 27.5 | −10.4 |

| Hesse | HE | 01.10.07 | 27.09.12 | 3 | 31.12.20 | ≤200/2,500 | Ban a,bc | 26.5 | −3.3 |

| M.-W. Pomerania | MV | 01.08.07 | 17.12.09 | 1 | 31.07.14 | ≤500/10,000 | Ban a,b | 33.9 | −5.6 |

| Lower Saxony | NI | 01.08.07 | 10.12.08 | 1 | None | (5–1,000) | Ban a,b | 28.0 | −5.7 |

| N. Rhine-Westphalia | NW | 01.01.08 | 04.12.12 | 2 | None | ≤2,500 | Ban c | 28.5 | −5.6 |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | RP | 15.02.08 | 26.05.09 | 1 | None | ≤500/1,000 | Ban a,b,c | 27.4 | −0.4 |

| Saarland | SL | 15.02.08 | 21.06.10 | 5 | 31.12.15 | ≤200/1,000 | Ban c | 27.2 | −3.5 |

| Saxony | SN | 01.02.08 | 01.07.12 | 4 | None | ≤5,000 | Ban a,b,c | 27.3 | 0.0 |

| Saxony-Anhalt | SA | 01.01.08 | 23.01.13 | 4 | None | (5–1,000) | Ban a,b | 32.9 | 6.5 |

| Schleswig-Holstein | SH | 01.01.08 | 25.04.09 | 1 | None | ≤1,000 | Ban a,b | 29.0 | −7.3 |

| Thuringia | TH | 01.07.08 | 31.12.12 | 2 | None | 20–200/50–500 | Ban a,b | 30.3 | 2.0 |

3.2. State Non-smoker Protection

3.3. Petitions, Popular Initiatives and Referendums on Non-smokers Protection

| Federal State | Title or Aim of Direct Democracy Initiative | Initiators | Stage | Start–End | Signatories (Quorum) | Formal Success (Factual Success) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bavaria | For real non-smokers protection (Für echten Nichtraucherschutz) | Action alliance of political parties, doctors, smoke-free society and others (Aktionsbündnis: ödp, Pro Rauchfrei e. V., Ärzte, SPD, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, andere) | 3 | 04.07.10 | — | 61% Approval rate (New smoke-free law [14]) |

| 2 | 19.11.09–02.12.09 | 1,300,000 (940,000) | Yes | |||

| 1 | 01. 05.09–17.07.09 | 40,300 (25,000) | Yes a | |||

| Against the non-smokers protection law (Gegen das Nichtraucherschutzgesetz) | The doers society (Die Macher e.V) | 1 | 26.01.08–January 2010 | 7,450 (25,000) | Ceased | |

| Brandenburg | Free smokers (Freie Raucher) | 1 | 16.01.08–November 2008 | 100 (20,000) | Ceased | |

| Berlin | Fresh air for Berlin (Frische Luft für Berlin) | Smoke-free societies and others (Forum Rauchfrei, Nichtraucherbund Berlin-Brandenburg e. V., Pro Rauchfrei e. V., andere) | 1 | 24.09.10–14.04.11 | 23,633 (20,000) | Yes (No) b,c |

| No smoking ban in pubs and restaurants in Berlin (Wahlfreiheit für Gäste und Wirte—kein Rauchverbot in Berliner Gaststätten) | Action alliance “Initiative for Consumption”—innkeepers (Aktionsbündnis “Initiative für Genuss”—Kneipen und Gastwirte) | 2 | 26.01.09–25.05.09 | 61,644 (171,000) | No | |

| 1 | 11.11.07–30.04.08 | 23,252 (20,000) | Yes | |||

| Hamburg | For true non-smokers protection—without exemptions (Für echten Nichtraucherschutz—ohne Ausnahmen) | Alliance of political party and smoke-free society (ödp, Nichtraucherschutz Hamburg e. V.) | 1 | 05.07.10–05.01.11 | <10,000 (10,000) | No |

| Against the non-smokers protection law (Gegen das Nichtraucherschutzgesetz) | Initiative “Smoking Rebels Hamburg”—individual innkeepers (Initiative “Hamburger Rauchrebellen”—einzelne Gastwirte) | 1 | 07.09.07–08.12.07 | 11,000 (10,000) | Yes (No) d | |

| Hesse | Against the revision of smoking bans (Gegen die Neuregelungen zum Rauchverbot) | The doers society (Die Macher e. V.) | 1 | 10.12.07–February 2010 | >50,000 (130,000) | Ceased a |

| Lower Saxony | Reform non-smokers protection law—for exemptions (Reform Nichtraucherschutzgesetz—für Ausnahmeregelungen) | Hotel and restaurant association lower saxony (Hotel-und Gaststättenverband Niedersachsen) | 1 | 26.11.07–25.11.08 | 66,210 (70,000) | No b |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | For better non-smokers protection (Für verbesserten Nichtraucherschutz) | Action alliance of pharmacists and others (Aktionsbündnis: Apotheken und andere) | 1 | 29.01.07–21.12.07 | Not available | Ceased e |

| Against the non-smokers protection law (Gegen das Nichtraucherschutzgesetz) | The doers society (Die Macher e.V) | 1 | 25.01.08–15.06.09 | 30 (3,000) | Ceased f | |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | Legalize smoking (Legalisierung von Rauchen) | 1 | 07.02.08–31.12.08 | 5,500 (20,000) | Ceased | |

| Saarland | 1 | 07.02.08–15.06.09 | 50 (5,000) | Ceased | ||

| Schleswig-Holstein | 1 | 01.01.08–15.06.09 | 8,150 (20,000) | Ceased | ||

| Thuringia | 1 | 01.01.08–15.06.09 | 800(5,000) | Ceased |

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interests

Supplementary Files

References

- Keil, U.; Heidrich, J.; Wellmann, J.; Heuschmann, P. Passivrauchbedingte Morbidität und Mortalität in Deutschland (Passive Smoking Related Morbidity and Mortality in Germany). In Rote Reihe Tabakprävention und Tabakkontrolle, Band 5; Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum: Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, S.; Kraus, L.; Piontek, D.; Pabst, A. Changes in exposure to secondhand smoke and smoking behavior. Sucht 2010, 56, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, L.; Pabst, A.; Piontek, D.; Müller, S. Kurzbericht Epidemiologischer Suchtsurvey 2009—Tabellenband: Prävalenz von Tabakkonsum, Nikotinabhängigkeit und Passivrauchen nach Geschlecht und Alter im Jahr 2009 (Prevalence of Tobacco Use, Nicotine Dependence and Passive Smoking by Sex and Age in 2009); Institut für Therapieforschung: München, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schenk, M.; Schaller, K.; Pötschke-Langer, M. Fakten zum Rauchen: Tabakrauch—Ein Giftgemisch (Facts about Smoking: Tobacco Smoke—A Toxic Mixture); Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum: Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, U.; Thielmann, H.W.; Pötschke-Langer, M. Fakten zum Rauchen: Krebserzeugende Substanzen im Tabakrauch (Facts about Smoking: Carcinogenic Substances in Tobacco Smoke); Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum: Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; World Health Organization: Geneva, Swizerland, 2005.

- Joossens, L.; Raw, M. Progress in Tobacco Control in 30 European Countries, 2005 to 2007; Association of European Cancer Leagues: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Joossens, L.; Raw, M. The Tobacco Control Scale 2010 in Europe; Association of European Cancer Leagues: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Verlag, C.H. Beck-online—Die Datenbank (The Database). Available online: http://beck-online.beck.de/ (accessed on 2 December 2013).

- Gesetz zur Einführung eines Rauchverbotes in Einrichtungen des Bundes und öffentlichen Verkehrsmitteln (Bundesnichtraucherschutzgesetz) (Law for the introduction of a smoking ban in federal facilities and public transport (Federal non-smokers protection act)). In Bundesgesetzblatt; 2007; I, pp. 1595–1597.

- Gesetz zum Schutz vor den Gefahren des Passivrauchens (Law to protect against the dangers of passive smoking). In Bundesgesetzblatt; 2007; I, pp. 1595–1597.

- Landesnichtraucherschutzgesetz (State non-smokers protection act). In Gesetzesblatt für Baden-Württemberg; 2007; pp. 337–339.

- Gesetz zum Schutz der Gesundheit (Gesundheitsschutzgesetz) (Law to protect health (Health protection act)). In Bayerisches Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt; 2007; pp. 919–921.

- Gesetz zum Schutz der Gesundheit (Gesundheitsschutzgesetz) (Law to protect health (Health protection act)). In Bayerisches Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt; 2010; pp. 314–316.

- Gesetz zum Schutz vor den Gefahren des Passivrauchens in der Öffentlichkeit (Nichtraucherschutzgesetz) (Law to protect against the dangers of passive smoking in public (Non-smokers protection act)). In Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt für Berlin; 2007; pp. 578–579.

- Gesetz zum Schutz vor den Gefahren des Passivrauchens in der Öffentlichkeit (Brandenburgisches Nichtrauchendenschutzgesetz) (Law to protect against the dangers of passive smoking in public (Brandenburg non-smokers protection act)). In Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt für das Land Brandenburg; 2007; I, pp. 346–347.

- Bremisches Nichtraucherschutzgesetz (Bremen non-smokers protection act). In Gesetzblatt der Freien Hansestadt Bremen; 2007; pp. 515–517.

- Hamburgisches Gesetz zum Schutz vor den Gefahren des Passivrauchens in der Öffentlichkeit (Hamburgisches Passivraucherschutzgesetz) (Hamburgian law to protect against the dangers of passive smoking in public (Hamburgian passive-smokers protection act)). In Hamburgisches Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt; 2007; I, pp. 211–212.

- Gesetz zum Schutz vor den Gefahren des Passivrauchens (Hessisches Nichtraucherschutzgesetz) (Law to protect against the dangers of passive smoking (Hessian non-smokers protection act)). In Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt für das Land Hessen; 2007; I, pp. 568–570.

- Nichtraucherschutzgesetz Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (Non-smokers protection act Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania). In Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt für Mecklenburg-Vorpommern; 2007; pp. 239–240.

- Niedersächsisches Gesetz zum Schutz vor den Gefahren des Passivrauchens (Niedersächsisches Nichtraucherschutzgesetz) (Lower saxony law to protect against the dangers of passive smoking (Lower saxony non-smokers protection act)). In Niedersächsisches Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt; 2007; pp. 337–338.

- Gesetz zur Verbesserung des Nichtraucherschutzes in Nordrhein-Westfalen (Law to improve non-smokers protection in North Rhine-Westphalia). In Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt für das Land Nordrhein-Westfalen; 2007; pp. 742–743.

- Nichtraucherschutzgesetz Rheinland-Pfalz (Non-smokers protection act Rhineland-Palatinate). In Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt für das Land Rheinland-Pfalz; 2007; pp. 534–536.

- Gesetz zum Schutz vor den Gefahren des Passivrauchens (Nichtraucherschutzgesetz) (Law to protect against the dangers of passive smoking (Non-smokers protection act)). In Amtsblatt des Saarlandes; 2008; I, pp. 75–78.

- Gesetz zur Wahrung des Nichtraucherschutzes im Land Sachsen-Anhalt (Nichtraucherschutzgesetz) (Law to preserve non-smokers protection in the state of Saxony-Anhalt (Non-smokers protection act)). In Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt für das Land Sachsen-Anhalt; 2007; pp. 464–465.

- Gesetz zum Schutz von Nichtrauchern im Freistaat Sachsen (Sächsisches Nichtraucherschutzgesetz) (Law on the protection of non-smokers in the free state of Saxony (Saxon non-smokers protection act)). In Sächsisches Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt; 2007; pp. 495–496.

- Gesetz zum Schutz vor den Gefahren des Passivrauchens (Law to protect against the dangers of passive smoking). In Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt für Schleswig-Holstein; 2007; pp. 485–486.

- Thüringer Gesetz zum Schutz vor den Gefahren des Passivrauchens (Thuringian law to protect against the dangers of passive smoking). In Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt für den Freistaat Thüringen; 2007; pp. 257–258.

- Parlamentsspiegel.de—Gemeinsames Informationssystem der Landesparlamente der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (Joint Information System of the State Parliaments of the Federal Republic of Germany). Available online: http://www.parlamentsspiegel.de/ (accessed on 27 December 2013).

- Aktionsbündnis Nichtrauchen e.V. Nichtraucherschutzgesetze der Einzelnen Bundesländer (State Non-smokers Protection Laws). Available online: http://www.abnr.de/index.php?article_id=18 (accessed on 27 December 2013).

- Bethke, C. Nichtraucherschutzgesetze der Einzelnen Bundesländer: Synopsen der Länderregelungen—Gaststätten (Non-smokers Protection Laws of the Individual States: Synopses of State Regulations—Pubs and Restaurants); Aktionsbündnis Nichtrauchen e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mach mit! Rauchfreies Saarland (Join! Smoke-free Saarland); Ministeriums für Gesundheit und Verbraucherschutz: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2011.

- Ministerium für Gesundheit, Emanzipation, Pflege und Alter des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen. Fragen und Antworten zum Nichtraucherschutzgesetz Nordrhein-Westfalen (Questions and Answers Regarding the Smoke-free Law of North Rhine-Westphalia). Available online: http://www.mgepa.nrw.de/gesundheit/praevention/nichtraucherschutz/fragen_und_antworten_zum_nichtraucherschutzgesetz_nordrhein-westfalen/ (accessed on 27 December 2013).

- Merk, R. Geschlossene Gesellschaft! Zu den Grenzen des Nichtraucherschutzes (Private function! On the limits of non-smokers protection). Publicus 2012, 5, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Volksbegehrensberichte 2000–2002 (Referendum Reports 2000–2002); Mehr Demokratie e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2003.

- Rehmet, F. Volksbegehrensberichte 2003–2012 (Referendum Reports 2003–2012); Mehr Demokratie e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gesetz über Ordnungswidrigkeiten (Ordnungswidrigkeitengesetz) (Administrative offence act). Bundesgesetzblatt 1987, 602–629.

- Mikrozensus—Fragen zur Gesundheit: Rauchgewohnheiten der Bevölkerung 2009 (Microcensus—Questions about Health: Smoking Habits of the Population 2009); Statistisches Bundesamt: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010.

- Deutsche Bahn. Hausordnung (Stand 06/2011) (House Rules (as of 06/2011)). Available online: http://www.deutschebahn.com/file/5122390/data/hausordnung.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2013).

- Jugendschutzgesetz (Youth protection act). In Bundesgesetzblatt; 2002; pp. 2730–2739.

- Verordnung über Arbeitsstätten (Arbeitsstättenverordnung) (Workplace regulations). In Bundesgesetzblatt; 2004; I, pp. 2179–2189.

- Nichtraucherschutz in Hotellerie und Gastronomie (Non-smokers Protection in Hotels and Gastronomic Facilities); Deutscher Hotel- und Gaststättenverband e.V., Bundesministerium für Gesundheit und Soziale Sicherung: Berlin, Germany, 2005.

- Erstes Gesetz zur Änderung des Nichtraucherschutzgesetzes (First act to amend the non-smokers protection law). In Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt für Berlin; 2009; 13, p. 250.

- Gesetz zur Änderung des Gesundheitsschutzgesetzes (Law to change the health protection act). In Bayerisches Gesetz- und Verordnungsblatt; 2009; p. 384.

- Rehmet, F. Volksentscheid Ranking 2013 (Referendum Ranking 2013); Mehr Demokratie e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Volksinitiative Frische Luft für Berlin. Abgeordnetenhaus will Keinen Verbesserten Schutz vor Passivrauch (House of Representatives does not Want Better Protection against Passive Smoke). Available online: http://www.forum-rauchfrei.de/files/Presseerklaerung_20.6.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2013).

- Martínez-Sánchez, J.M.; Fernández, E.; Fu, M.; Gallus, S.; Martínez, C.; Sureda, X.; la Vecchia, C.; Clancy, L. Smoking behaviour, involuntary smoking, attitudes towards smoke-free legislations, and tobacco control activities in the European Union. PLoS One 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mons, U.; Nagelhout, G.E.; Guignard, R.; McNeill, A.; van den Putte, B.; Willemsen, M.C.; Brenner, H.; Pötschke-Langer, M.; Breitling, L.P. Comprehensive smoke-free policies attract more support from smokers in Europe than partial policies. Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 22, S10–S16. [Google Scholar]

- Reuband, K.-H. Tabakkonsum im gesellschaftlichen Wandel. Verbreitung des Konsums und Einstellung zu Rauchverboten, Düsseldorf 1997–2009 (Tobacco consumption in a changing society. Extent of consumption and attitudes to smoking bans, Düsseldorf 1997–2009). Gesundheitswesen. in press.

- Gleich, F.; Mons, U.; Pötschke-Langer, M. Air contamination due to smoking in German restaurants, bars, and other venues—Before and after the implementation of a partial smoking ban. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2011, 13, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anger, S.; Kvasnicka, M.; Siedler, T. One last puff? Public smoking bans and smoking behavior. J. Health Econ. 2011, 30, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuehnle, D.; Wunder, C. The effects of smoking bans on self-assessed health: Evidence from Germany; SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research 586; German Institute for Economic Research: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nagelhout, G.E.; Mons, U.; Allwright, S.; Guignard, R.; Beck, F.; Fong, G.T.; de Vries, H.; Willemsen, M.C. Prevalence and predictors of smoking in “smoke-free” bars. Findings from the international tobacco control (ITC) Europe surveys. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 1643–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüderl, J.; Ludwig, V. Does a smoking ban reduce smoking? Evidence from Germany. Schmollers Jahrbuch 2011, 131, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvasnicka, M.; Tauchmann, H. Much ado about nothing? Smoking bans and Germany’s hospitality industry. Appl. Econ. 2012, 44, 4539–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Kohler, S.; Minkner, P. Smoke-Free Laws and Direct Democracy Initiatives on Smoking Bans in Germany: A Systematic Review and Quantitative Assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 685-700. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110100685

Kohler S, Minkner P. Smoke-Free Laws and Direct Democracy Initiatives on Smoking Bans in Germany: A Systematic Review and Quantitative Assessment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014; 11(1):685-700. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110100685

Chicago/Turabian StyleKohler, Stefan, and Philipp Minkner. 2014. "Smoke-Free Laws and Direct Democracy Initiatives on Smoking Bans in Germany: A Systematic Review and Quantitative Assessment" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11, no. 1: 685-700. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110100685