How Has the Availability of Snus Influenced Cigarette Smoking in Norway?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Overall Tobacco Consumption

2.2. Use of Snus in Quit-Smoking Attempts

2.3. Quit Ratio for Smoking

| Survey | Year | Number of Ever-Smokers | Age Group | Daily Snus User | Never Used Snus | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | ||||||

| 1 | 2003–2008 | 3604 | 16–74 | 80.4 (74.9–85.9) | 51.9 (50.1–53.7) | < 0.001 |

| 2 | 2007 | 423 | 16–20 | 54.8 (45.2–64.9) | 22.9 (17.4–28.4) | < 0.001 |

| 3 | 2006 | 458 | 19–30 | 81.1 (68.5–93.7) | 62.7 (56.9–68.4) | 0.010 |

| 4 | 2007 | 2016 | 15–91 | 61.6 (53.5–69.7) | 52.5 (50.2–54.8) | 0.035 |

| 5 | 2006 | 729 | 21–30 | 75.4 (65.2–85.6) | 44.9 (40.2–49.6) | < 0.001 |

| 6 | 2006 | 639 | 21–30 | 89.7 (81.9–97.5) | 50.0 (45.1–54.9) | < 0.001 |

| 7 | 2007 | 2572 | 20–50 | 72.7 (81.9–97.5) | 43.3 (40.6–46.0) | < 0.001 |

| 8 | 2009–2013 | 1543 | 15–74 | 80.8 (75.4–86.2) | 55.7 (52.9–58.5) | < 0.001 |

| 9 | 2009–2013 | 2777 | 15–80 | 74,6 (69.8–79.4) | 65.5 (63.6–67.5) | < 0.001 |

| Total | -- | 14,761 | Weighted mean | 74.8 (72.8–76.8) | 52.3 (51.4–53.2) | < 0.001 |

| Females | ||||||

| 8 | 2009–13 | 1472 | 15–74 | 85.7 (75.0–95.2) | 52.0 (49.4–54.6) | < 0.001 |

| 9 | 2009–13 | 3036 | 15–80 | 74.8 (65.8–83.8) | 61.6 (59.8–63.4) | < 0.001 |

| Total | -- | 4508 | Weighted mean | 78.4 (71.5–85.3) | 56.1 (54.6–57.6) | < 0.001 |

2.4. Smoking Initiation

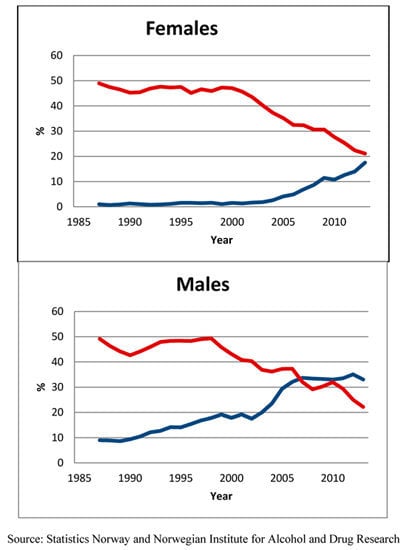

3. Results

4. Discussion

Transfer Value to E-Cigarettes

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Conflicts of interest

References

- Adkison, S.E.; O’Connor, R.J.; Bansal-Travers, M.; Hyland, A.; Borland, R.; Yong, H.H.; Cummings, K.M.; McNeill, A.; Thrasher, J.F.; Hammond, D.; et al. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: international tobacco control four-country survey. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, K.E. Association between willingness to use snus to quit smoking and perception of relative risk between snus and cigarettes. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2012, 14, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, D.T.; Mumford, E.A.; Cummings, K.M.; Gilpin, E.A.; Giovino, G.; Hyland, A.; Sweanor, D.; Warner, K.E. The relative risks of a low-nitrosamine smokeless tobacco product compared with smoking cigarettes: Estimates of a panel of experts. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2004, 13, 2035–2042. [Google Scholar]

- Nutt, D.J.; Phillips, L.D.; Balfour, D.; Curran, H.V.; Dockrell, M.; Foulds, J.; Fagerstrom, K.; Letlape, K.; Milton, A.; Polosa, R.; et al. Estimating the harms of nicotine-containing products using the MCDA approach. Eur. Addict. Res. 2014, 20, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timberlake, D.S.; Pechmann, C.; Tran, S.Y.; Au, V. A content analysis of Camel Snus advertisements in print media. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2011, 13, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, I.; Scheffels, J. Perceptions of relative risk of disease and addiction from cigarettes and snus. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014, 28, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Holm, L.; Fisker, J.; Larsen, B.I.; Puska, P.; Halldórsson, M. Snus does not save lives: Quitting smoking does! Tob. Control 2009, 18, 250–251. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2014/40/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 on the Approximation of the Laws, Regulations and Administrative Provisions of the Member States Concerning the Manufacture, Presentation and Sale of Tobacco and Related Products and Repealing. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/health/tobacco/docs/dir_201440_en.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2014).

- German Cancer Research Center. Electronic Cigarettes—An Overview; Tobacco Prevention and Tobacco Control: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, S. Should electronic cigarettes be as freely available as tobacco cigarettes? Br. Med. J. 2013, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynas, K. Public health watch. Canadian Pharmacists Journal/Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada 2013, 146, 316–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trtchounian, A.; Talbot, P. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: Is there a need for regulation? Tob. Control 2011, 20, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Selection of metric for regulation. In Regulatory Scope. Tobacco Product Regulation; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Etter, J.-F.; Bullen, C.; Flouris, A.D.; Laugesen, M.; Eissenberg, T. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: A research agenda. Tob. Control 2011, 20, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatsukami, D.K.; et al. Reducing tobacco harm: Research challenges and issues. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2002, 4, S89–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansson, J.; Galanti, M.R.; Hergens, M.P.; Fredlund, P.; Ahlbom, A.; Alfredsson, L.; Bellocco, R.; Eriksson, M.; Hallqvist, J.; Hedblad, B.; et al. Use of snus and acute myocardial infarction: Pooled analysis of eight prospective observational studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 27, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.N. Epidemiological evidence relating snus to health—An updated review based on recent publications. Harm Reduct. J. 2013, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, E.K.; Lund, M.; Bryhni, A. Tobacco consumption among men and women 1927–2007. Tidsskr. Norsk Lægeforen. 2009, 129, 1871–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, K.E. Omfanget av grensehandel, taxfreeimport og smugling av tobakk til Norge (The scale of border trade, tax-free imports and tobacco smuggling to Norway). Tidsskr. Norsk Lægeforen. 2004, 124, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer and World Health Organization (IARC/WHO). Methods for Evaluating Tobacco Control Policies; Handbook; IARC/WHO: Lyon, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, E.K.; Scheffels, J.; McNeill, A. The association between use of snus and quit rates for smoking: Results from seven Norwegian cross-sectional studies. Addiction 2011, 106, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellevik, O. Jakten På Den Norske Lykken (On the Lookout for the Norwegian Happiness); Norsk monitor 1985–2007; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, E.K.; McNeill, A.; Scheffels, J. The use of snus for quitting smoking compared with medicinal products. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010, 12, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, E.K.; McNeill, A. Patterns of dual use of snus and cigarettes in a mature snus market. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013, 15, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramström, L.M.; Foulds, J. Role of snus in initiation and cessation of tobacco smoking in Sweden. Tobacco Control 2006, 15, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stegmayr, B.; Eliasson, M.; Rodu, B. The decline of smoking in northern Sweden. Scand. J. Public Health 2005, 33, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilljam, H.; Galanti, M.R. Role of snus (oral moist snuff) in smoking cessation and smoking reduction in Sweden. Addiction 2003, 98, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norberg, M.; Lundqvist, G.; Nilsson, M.; Gilljam, H.; Weinehall, L. Changing patterns of tobacco use in a middle-aged population–the role of snus, gender, age, and education. Glob. Health Action 2011, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg, M.; Malmberg, G.; Ng, N.; Broström, G. Who is using snus? Time trends, socioeconomic and geographic characteristics of snus users in the ageing Swedish population. BMC Public Health 2011, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenbeck, M.; Hagquist, C.; Rosén, M. The association of snus and smoking behaviour: A cohort analysis of Swedish males in the 1990s. Addiction 2009, 104, 1579–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodu, B.; Stegmayr, B.; Nasic, S.; Asplund, K. Impact of smokeless tobacco use on smoking in northern Sweden. J. Intern. Med. 2002, 252, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodu, B.; Stegmayr, B.; Nasic, S.; Cole, P.; Asplund, K. Evolving patterns of tobacco use in northern Sweden. J. Intern. Med. 2003, 253, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, S.P.; Campbell, M.L.; Temporale, K.; Good, K.B. The acute effect of Swedish‐style snus on cigarette craving and self‐administration in male and female smokers. Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. 2011, 26, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, D.; Chakravorty, B.; Weeks, K.; Flay, B.R.; Dent, C.; Stacy, A.; Sussman, S. Outcome of a tobacco use cessation randomized trial with high-school students. Subst. Use Misuse 2009, 44, 965–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, B.; Burgess, C.; Crane, J. Randomized crossover trial of the acceptability of snus, nicotine gum, and Zonnic therapy for smoking reduction in heavy smokers. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010, 12, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, J.M.; Gray, K.M. A pilot randomized study of smokeless tobacco use among smokers not interested in quitting: Changes in smoking behaviour and readiness to quit. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010, 12, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagerstrom, K.; Rutqvist, L.E.; Hughes, J.R. Snus as a smoking cessation aid: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2012, 14, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joksić, G.; et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of Swedish snus for smoking reduction and cessation. Harm Reduct. J. 2011, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunell, E.; Curvall, M. Nicotine delivery and subjective effects of Swedish portion snus compared with 4 mg nicotine polacrilex chewing gum. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2011, 13, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheffels, J.; Lund, K.E.; McNeill, A. Contrasting snus and NRT as methods to quit smoking: An observational study. Harm Reduct. J. 2012, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, W.; Soest, T. Tobacco use among Norwegian adolescents: From cigarettes to snus. Addiction 2014, 109, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, E.; Rise, J.; Lund, K. Risk and protective factors of adolescent exclusive snus users compared to non-users of tobacco, exclusive smokers and dual users of snus and cigarettes. Addict. Behav. 2013, 38, 2288–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sæbø, G. Cigarettes, snus and status. About life-style differences between users of various tobacco products. Nor. J. Sociol. 2013, 21, 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tobakk-Og Rusmiddelbruk Blant unge Voksne I Norge. Available online: http://www.sirus.no/filestore/Automatisk_opprettede_filer/Tobakkogrusmiddelbrukblantungevoksneinorge.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2014).

- Norwegian Institute for Public Health. Smoking and Smokeless Tobacco in Norway–Fact Sheet; Norwegian Institute for Public Health: Oslo, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Øverland, S.; Hetland, J.; Aarø, L.E. Relative harm of snus and cigarettes: What do Norwegian adolescents say? Tob. Control 2008, 17, 422–425. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, I.; Scheffels, J. Perceptions of the relative harmfulness of snus among Norwegian general practitioners and their effect on the tendency to recommend snus in smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2012, 14, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biener, L.; Nyman1, A.L.; Stepanov, I.; Hatsukami, D. Public education about the relative harm of tobacco products: An intervention for tobacco control professionals. Tob. Control 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, I.; Jensen, J.; Hatsukami, D.; Hecht, S.S. New and traditional smokeless tobacco: Comparison of toxicant and carcinogen levels. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2008, 10, 1773–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, I.; Villalta, P.W.; Knezevich, A.; Jensen, J.; Hatsukami, D.; Hecht, S.S. Analysis of 23 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in smokeless tobacco by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009, 23, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, I.; Gupta, P.C.; Dhumal, G.; Yershova, K.; Toscano, W.; Hatsukami, D.; Parascandola, M. High levels of tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines and nicotine in Chaini Khaini, a product marketed as snus. Tob. Control 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, I.; Biener, L.; Knezevich, A.; Nyman, A.L.; Bliss, R.; Jensen, J.; Hecht, S.S.; Hatsukami, D.K. Monitoring tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines and nicotine in novel smokeless tobacco products: Findings from round II of the new product watch. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014, 16, 1070–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, P.; Etter, J.F.; Benowitz, N.; Eissenberg, T.; McRobbie, H. Electronic cigarettes: Review of use, content, safety, effects on smokers and potential for harm and benefit. Addiction 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biener, L.; Roman, A.M.; Mc Inerney, S.A.; Bolcic-Jankovic, D.; Hatsukami, D.K.; Loukas, A.; O’Connor, R.J.; Romito, L. Snus use and rejection in the USA. Tob. Control 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, J.F.; Bullen, C. Electronic cigarette: Users profile, utilization, satisfaction and perceived efficacy. Addiction 2011, 106, 2017–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbeau, M.A.; Burda, J.; Siegel, M. Perceived efficacy of e-cigarettes versus nicotine replacement therapy among successful e-cigarette users: A qualitative approach. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, A.; Tower, S.; Sumner, W. Interviews with “vapers”: Implications for future research with electronic cigarettes. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2011, 13, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timberlake, D.S. Are smokers receptive to using smokeless tobacco as a substitute? Prev. Med. 2009, 49, 229–232. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner, C.; Jimenez-Soto, E.V.; Borland, R.; O’Connor, R.J.; Hall, W.D. Are Australian smokers interested in using low-nitrosamine smokeless tobacco for harm reduction? Tob. Control 2010, 19, 451–456. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.H.; Wang, J.B.; Hartman, A.; Zhuang, Y.; Gamst, A.; Gibson, J.T.; Gilljam, H.; Galanti, M.R. Quitting cigarettes completely or switching to smokeless tobacco: Do US data replicate the Swedish results? Tob. Control 2009, 18, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lund, I.; Lund, K.E. How Has the Availability of Snus Influenced Cigarette Smoking in Norway? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 11705-11717. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111111705

Lund I, Lund KE. How Has the Availability of Snus Influenced Cigarette Smoking in Norway? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014; 11(11):11705-11717. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111111705

Chicago/Turabian StyleLund, Ingeborg, and Karl Erik Lund. 2014. "How Has the Availability of Snus Influenced Cigarette Smoking in Norway?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11, no. 11: 11705-11717. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111111705