Developing a Service Platform Definition to Promote Evidence-Based Planning and Funding of the Mental Health Service System

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

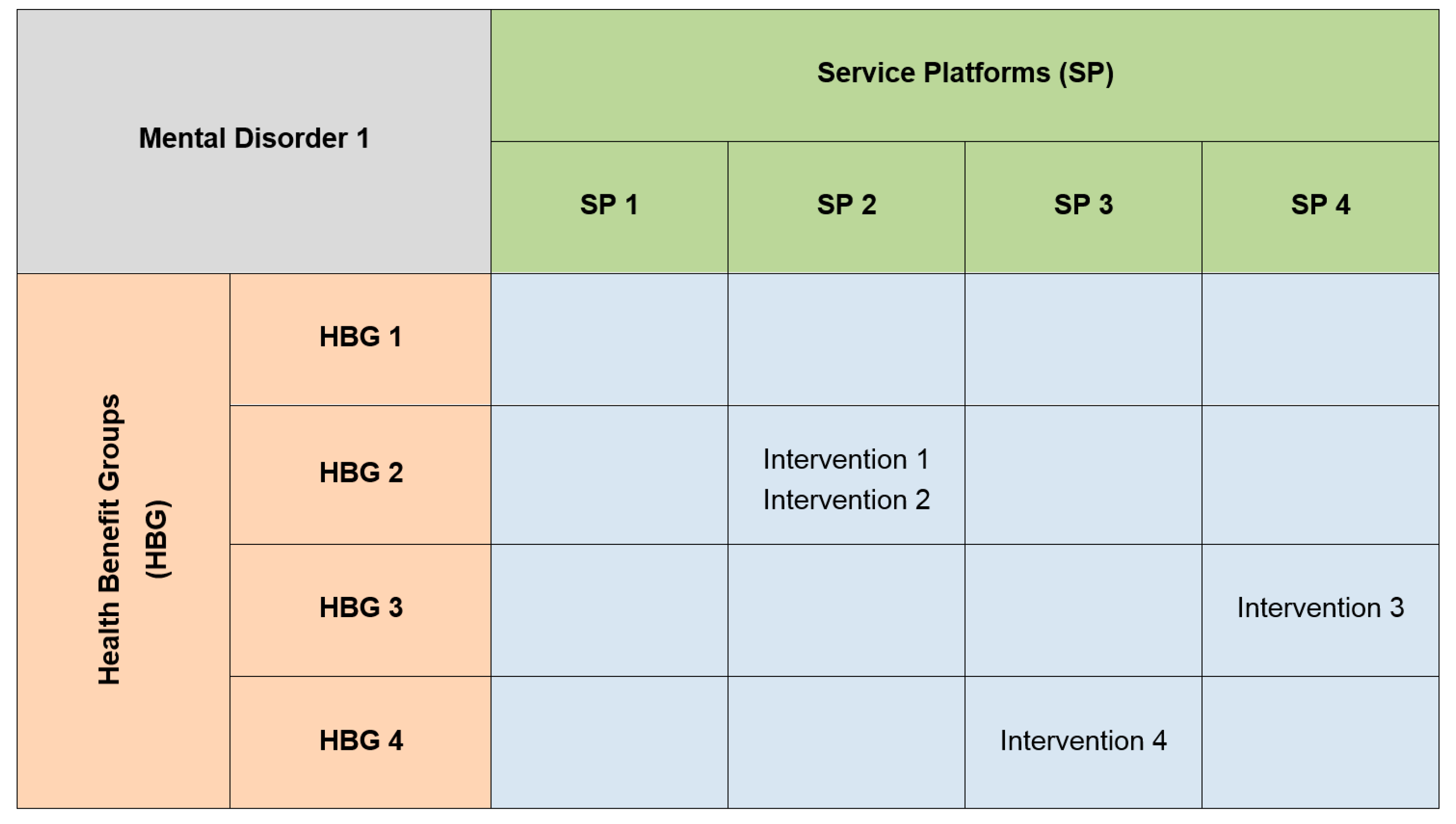

2.1. Developing a Definition of a Service Platform

2.2. Testing the Validity of the Definition

2.2.1. Recruiting a Sample of Mental Health Policy Makers

2.2.2. Procedure for Validating the Proposed Definition

2.2.3. Analysis of Transcripts

| One definition of a service platform is: “A service platform is a grouping of related services that are similar in resource type and constitute a component of a continuum of care.” | |

|---|---|

| Q1. | Can you tell us if this definition of a Service Platform is consistent with how you think the health system is organised? Why or why not? |

| Q2. | Does this concept make sense to you? Why or why not? |

| Q3. | Can you provide us with examples of Service Platforms? |

| Q4. | Do you think this definition of a Service Platform is a useful way to conceptualise the mental health system? Why or why not? |

| Q5. | Do you think this definition of a Service Platform delineates different types of services in a way that is helpful for planning and funding? |

| Q6. | Is there anything else about the Service Platform concept that you would like to share with us? |

| Framework of Analysis | Code |

|---|---|

| Acceptability (Q1) | EXP ACC (explicit acceptance) |

| PART ACC (partial acceptance) | |

| EXP REJ (explicit rejection) | |

| Comprehensibility (Q2) | EXP COMP (explicit comprehension) |

| TAC & COND COMP (tacit and conditional comprehension) | |

| EXP NOT COMP (explicitly does not comprehend) | |

| User generated examples (Q3) | CONV (convergent understanding of service platforms) |

| DIV (divergent understanding of service platforms) | |

| Usefulness (Q4–Q5) | EXP USE (explicit usefulness) |

| TAC USE (tacit usefulness) | |

| COND USE (conditional usefulness) | |

| EXP NOT USE (explicitly states that the definition is not useful) |

3. Results

3.1. Developing a Definition of a Service Platform

“A service platform is a grouping of related services that are similar in resource type and constitute a component of a continuum of care.”

3.2. Testing the Validity of the Definition

3.2.1. Acceptability of the Service Platform Definition (Q1)

“Yes. In mental health we could think of community based services and bed based services as two service platforms given the current model of funding and comparability of function. […] So the definition is reasonable but may still need to be further broken down depending on the use.”[Respondent 2]

“This is an “ideal” definition for the purposes of model building. The service is not organized in a completely rational manner and is the consequence of historical and societal influences. […] Current services are not usually organized along a continuum of care (although I believe they should be).”[Respondent 8]

“To some extent, but I worry about there being no mention of the service platform being related to the needs of the service population.”[Respondent 5]

“The health system is currently organized largely on source of funding not necessarily on the grouping of related services to be delivered. So in this sense I do not think a ‘Service Platform’ is consistent with the way the system is organized, however, I do believe that if we are to have a reflection of the continuum of care, a service platform approach is a good way of doing it.”[Respondent 6]

3.2.2. Comprehensibility of the Service Platform Definition (Q2)

“This concept does make sense to me. In the development of the National Mental Health Services Planning Framework (NMHSPF) we attempted to categorise the system in a hierarchical taxonomy of Service Group/Stream/Category/Element/Activity/Quantification.”[Respondent 6]

“I believe the definition would be a good starting point for model construction, if it also included the concept of “problem or disorder type” as well as resource type and continuum of care.”[Respondent 8]

“The concept seems to presume the existence of a “continuum of care”, but this is not something that many experience. Many experience fragments of service, largely disconnected from each other. Too often components of a system are considered on their own, rather than as a link in a chain that requires many components if any one component is to be successful.”[Respondent 9]

“Not really—I’m confused as to why a ‘grouping’ is only a ‘component’.”[Respondent 1]

3.2.3. Examples of Service Platforms Provided by Respondents (Q3)

“In the current system […] I think there is a fairly common understanding of related services that are delivered through a community based platform, bed based, outreach etc. Within each there is a different range of service types provided although with some overlap—e.g., medication information and provision, family/psychological interventions. The platforms are accessed at different phases of care and mostly form a continuum.”[Respondent 2]

“In patient care, primary care, psychosocial support”[Respondent 9]

“Acute Inpatient services grouped older persons, adult, child and youth. Community continuing care teams split older persons, adult, child and youth. Acute care teams general adult. High security inpatient services etc.”[Respondent 3]

“Some examples of Service Platforms might include collaborative care models in primary for depressive disorders, services for neuro-degenerative disorders (Huntington’s Disorder Services in Victoria), Mothers and Babies Services.”[Respondent 8]

“headspace is an example of a service platform that seeks to link consumers through a single point of contact to a range of services.”[Respondent 4]

“A bit tricky because I’m not clear, but my guess is most chronic disease management protocols would look something like this.”[Respondent 1]

3.2.4. Usefulness of Service Platform Concept in Conceptualizing the Mental Health System (Q4)

“Well, we certainly aspire to see a number of related service elements/interventions grouped concurrently and/or sequentially, so that we make adequate and complementary responses that address all the life domains relevant to the person with that illness. With severe low prevalence mental illness that is a lot of service elements.”[Respondent 1]

“Service platforms will group services in a similar fashion to our Models of Service. It should group on target group, staffing capability, interventions offered and expected deliverables”[Respondent 3]

“I think the utility depends on how resource allocation is determined. […] If the platform included too many subunits, it would lose utility.”[Respondent 2]

“[Yes] if the definition of a Service Platform for mental health includes reference to the people we are trying to service. Without such a reference there is a risk that the individual with the disorder will be lost in the higher level focus of the definition. […] the definition makes no reference at all to the consumers and their disorders.”[Respondent 5]

“No, as currently defined, it is more applicable to defining an element or a cluster of the elements of the mental health system rather than the system itself. In this context I think it has limitations currently, in particular the words ‘component of’ a continuum of care. There is merit in considering the definition of a service platform in the context of a definition of the mental health system.”[Respondent 4]

3.2.5. Usefulness of Service Platform Concept in Planning and Funding (Q5)

“It is a helpful delineation. If expected Service Platform utilization is understood from population size and demography existing capacity can be mapped, the gap understood and then planning for staged growth, addressing areas of greatest need first can be progressed.”[Respondent 3]

“Yes, it will assist in delineating elements of the service system and understanding a system, current or ideal. To be of assistance for planning and funding, it will require to [sic] move beyond definitions and refined to include values.”[Respondent 4]

“Linked to an outcome analysis, this kind of definition may help us to decide what kinds of service platforms, or resource types, are most efficiently and effectively applied to achieve certain outcomes.”[Respondent 9]

“[A related framework] set out to define each component of an area based mental health service, including those elements that should be in each area, and those that would be regional or state-wide specialist. I think [the framework] worked well when funding was relatively high. With progressive reduction in funding in real terms, these component parts have been lost or rolled into a more integrated function—e.g., primary mental health, acute assessment, continuing care, etc. So I think to make the platform concept of use also requires consideration of the population covered and the overall resourcing.”[Respondent 2]

3.2.6. Suggested Changes to the Service Platform Definition

| Respondent | Alternative Terminology Used by Respondent |

|---|---|

| 1 | Respondent initially understood service platform in terms of ‘packages’ (cf. ‘care packages’ used in NMHSPF). Also referred to ‘service elements’ and ‘interventions grouped concurrently and/or sequentially’. |

| 2 | Referenced terminology related to the hierarchical taxonomy of services produced by the NMHSPF—i.e., ‘service group’, ‘service stream’, ‘service category’, ‘service element’, ‘service activity’. |

| 3 | Related the service platform concept and the way it grouped services to a ‘Models of Service’ concept. |

| 4 | Understood a service platform to be a ‘cluster of the elements in the mental health system’. |

| 7 | Respondent used the terms ‘service clusters’ or ‘service constellations’ to refer to groupings of services in the mental health system. |

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Findings

4.2. Moving forward with the Development of the Service Platform Concept

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Files

Supplementary File 1Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whiteford, H.A.; Degenhardt, L.; Rehm, J.; Baxter, A.J.; Ferrari, A.J.; Erskine, H.E.; Charlson, F.J.; Norman, R.E.; Flaxman, A.D.; Johns, N.; et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from The Global Burden Of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013, 382, 1575–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, D.E.; Cafiero, E.T.; Jané-Llopis, E.; Abrahams-Gessel, S.; Bloom, L.R.; Fathima, S.; Feigl, A.B.; Gaziano, T.; Mowafi, M.; Pandya, A.; et al. The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere, K.; Bruffaerts, R.; Posada-Villa, J.; Gasquet, I.; Kovess, V.; Lepine, J.P.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Bernert, S.; de Girolamo, G.; Morosini, P.; et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. JAMA 2004, 291, 2581–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.; Maj, M.; Flisher, A.J.; De Silva, M.J.; Koschorke, M.; Prince, M.; WPA Zonal; Member Society Representatives. Reducing the treatment gap for mental disorders: A WPA survey. World Psychiatry 2010, 9, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saxena, S.; Thornicroft, G.; Knapp, M.; Whiteford, H. Resources for mental health: Scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 2007, 370, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochefort, D.A. Policymaking cycles in mental health: Critical examination of a conceptual model. J. Health Polit. Policy Law 1988, 13, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingdon, J.W. Alternatives, and Public Policies; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford, H.; Harris, M.; Diminic, S. Mental health service system improvement: Translating evidence into policy. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2013, 47, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medibank and Nous Group. The Case for Mental Health Reform in Australia: A Review of Expenditure and System Design. Available online: https://www.medibankhealth.com.au/Mental_Health_Reform (accessed on 10 December 2013).

- World Health Organization. Economic Aspects of the Mental Health System: Key Messages to Health Planners and Policy Makers; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. vesting in Mental Health: Evidence for Action; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, R.; Vos, T.; Moodie, M.; Haby, M.; Magnus, A.; Mihalopoulos, C. Priority setting in health: Origins, description and application of the Australian assessing cost-effectiveness initiative. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2008, 8, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihalopoulos, C.; Carter, R.; Pirkis, J.; Vos, T. Priority-setting for mental health services. J. Ment. Health 2013, 22, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beeharry, G.B.; Whiteford, H.; Chambers, D.; Baingana, F. Outlining the Scope for Public Sector Involvement in Mental Health: A Discussion Paper; World Bank: Washington DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, G. Tolkien II: A Needs-Based, Costed, Stepped-Care Model for Mental Health Services; World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Classification in Mental Health: Sydney, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, M. Tolkien III—Optimal Health and Education Service Pathways for Children and Adolescents with Mental Disorder—Final Report; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vos, T.; Carter, R.; Barendregt, J.J.; Mihalopoulos, C.; Veerman, J.L.; Magnus, A.; Cobiac, L.; Bertram, M.Y. ACE-Prevention Team. In Assessing Cost-Effectiveness in Prevention (Ace-Prevention): Final Report; University of Queensland, Brisbane and Deakin University: Melbourne, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vos, T.; Haby, M.M.; Magnus, A.; Mihalopoulos, C.; Andrews, G.; Carter, R. Assessing cost-effectiveness in mental health: Helping policy-makers prioritize and plan health services. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2005, 39, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Dynamics Economics and Policy. Disease Control Priorities Network (DCPN). Available online: http://www.cddep.org/projects/disease_control_priorities_project (accessed on 3 September 2013).

- Center for Global Health Research. Disease Control Priorities Network (DCPN). Available online: http://www.cghr.org/index.php/projects/disease-control-priorities-network-dcpn/ (accessed on 3 September 2013).

- Department of Global Health. DCP3—Disease Control Priorities—Economic Evaluation for Health. Available online: http://www.dcp-3.org/ (accessed on 2 July 2014).

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Research Areas: Cost Effectiveness. Available online: http://www.healthmetricsandevaluation.org/research/team/cost-effectiveness (accessed on 3 September 2013).

- Thornicroft, G.; Tansella, M. The Mental Health Matrix: A Manual to Improve Services; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S.; Kuhlmann, R.; EPCAT Group; European Psychiatric Assessment Team. The European Service Mapping Schedule (ESMS): Development of an instrument for the description and classification of mental health services. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000, 405, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centre of Research Excellence in Mental Health Systems Improvement. CREMSI—Our Team. Available online: http://mhsystems.org.au/investigators/ (accessed on 2 July 2014).

- Barry, M.; Jenkins, R. Implementing Mental Health Promotion; Elsevier: Edinburgh, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care. Promotion, Prevention and Early Intervention for Mental Health: A Monograph; Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care: Canberra, Australia, 2000.

- Mrazek, P.J.; Haggerty, R.J. Reducing the Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research; National Academy Press: Washington DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rickwood, D. Pathways of Recovery: Preventing Further Episodes of Mental Illness (Monograph); Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver, C.; Zhao, Y. Investment Analysis of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care Program in the Northern Territory; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Primary Health Care Review: Consultant Report No. 2; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver, C.; Zhao, Y.; Skov, S.; Morton, H. Health benefit and health care resource group classifications: Linking health care needs to resource requirements across the health care sector. Casemix 2000, 2, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Eagar, K.; Brewer, C.; Collins, J.; Fildes, D.; Findlay, C.; Green, J.; Harrison, L.; Harwood, N.; Marosszeky, N.; Masso, M.; et al. Strategies for Gain—The Evidence on Strategies to Improve the Health and Wellbeing of Victorian Children; Centre for Health Service Development, University of Wollongong: Wollongong, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. National Mental Health Service Planning Framework (NMHSPF). Available online: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-nmhspf (accessed on 9 July 2014).

- Centre of Research Excellence in Mental Health Systems Improvement. NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Mental Health Systems Improvement (CREMSI). Available online: http://mhsystems.org.au/ (accessed on 3 September 2013).

- Hasson, F.; Keeney, S.; McKenna, H. Research guidelines for the delphi survey technique. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 32, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Landeta, J. Current validity of the delphi method in social sciences. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2005, 73, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Sandford, B.A. The Delphi Technique: Making sense of consensus. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2007, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Given, L.M. The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 195–196. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, Y.Y.; Meurk, C.S.; Harris, M.G.; Diminic, S.; Scheurer, R.W.; Whiteford, H.A. Developing a Service Platform Definition to Promote Evidence-Based Planning and Funding of the Mental Health Service System. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 12261-12282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111212261

Lee YY, Meurk CS, Harris MG, Diminic S, Scheurer RW, Whiteford HA. Developing a Service Platform Definition to Promote Evidence-Based Planning and Funding of the Mental Health Service System. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014; 11(12):12261-12282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111212261

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Yong Yi, Carla S. Meurk, Meredith G. Harris, Sandra Diminic, Roman W. Scheurer, and Harvey A. Whiteford. 2014. "Developing a Service Platform Definition to Promote Evidence-Based Planning and Funding of the Mental Health Service System" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11, no. 12: 12261-12282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111212261