Drinking and Driving among Recent Latino Immigrants: The Impact of Neighborhoods and Social Support

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2. Research Aims

1.3. Neighborhoods and Alcohol Use

1.4. Social Support

1.5. Acculturative Stress

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analytic Plan

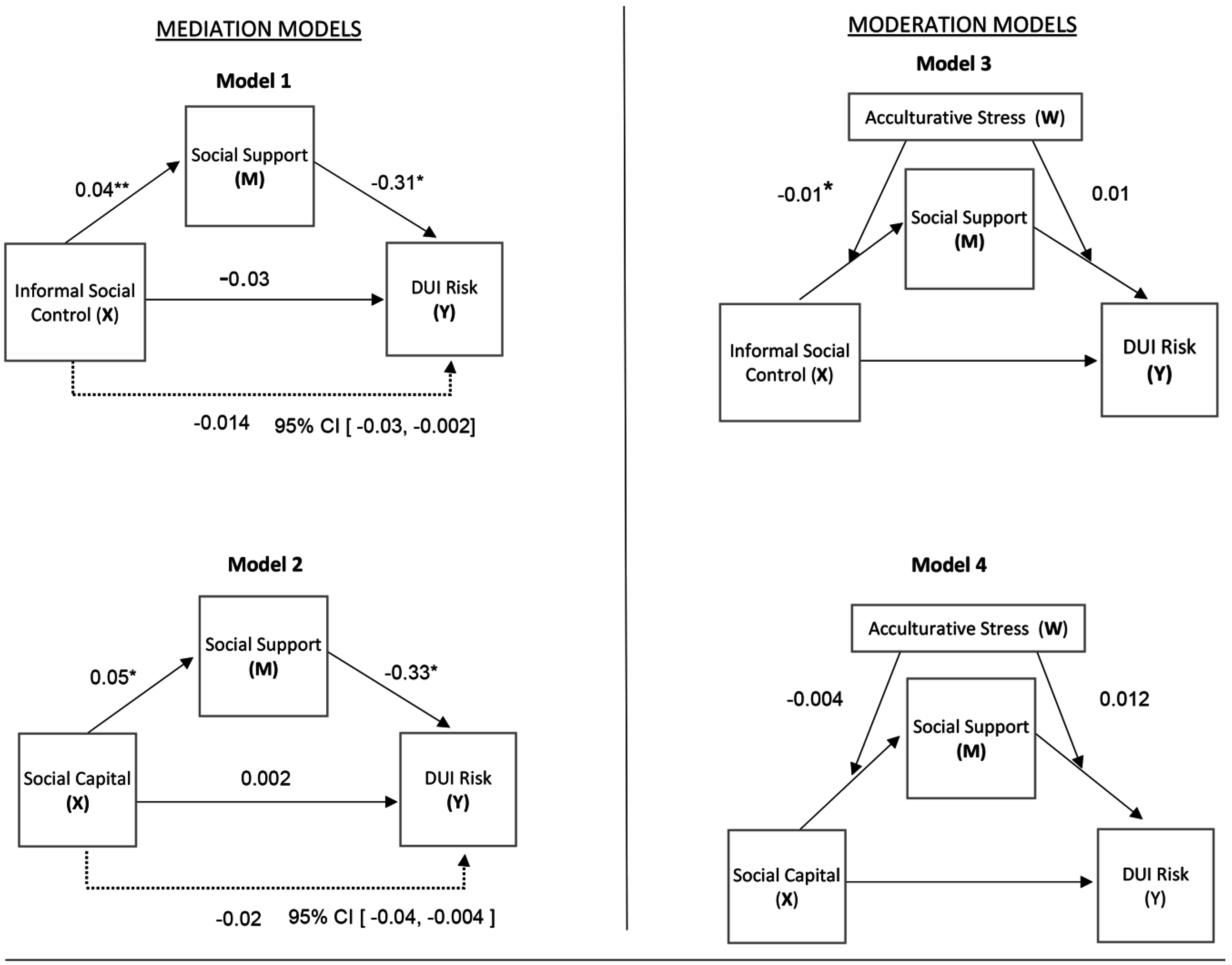

2.4. Primary Analysis

3. Results

Primary Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Institutes of Health. NIH Announces Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Available online: https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-announces-institute-minority-health-health-disparities (accessed on 13 October 2016).

- National Traffic Safety Administration. Promising Practices for Addressing Alcohol-Impaired Driving within Latino Populations: A NHTSA Demonstration Project. 2010. Available online: http://www.preventimpaireddriving.org/other-resources/helpful-websites/ (accessed on 5 September 2016).

- National Traffic Safety Administration. Race and Ethnicity: Factors in Fatal Motor Vehicle Traffic Crashes 1999–2004. 2006. Available online: https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/809956 (accessed on 5 September 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Caetano, R.; McGrath, C. Driving under the influence (DUI) among U.S. ethnic groups. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2005, 37, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherpitel, C.J.; Tam, T.W. Variables associated with DUI offender status among Whites and Mexican Americans. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2000, 61, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, R.; Clark, C.L. Trends in alcohol consumption patterns among whites, blacks, and Hispanics: 1984 and 1995. J. Stud. Alcohol 1998, 59, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Highway Safety Needs of U.S. Hispanic Communities: ISSUES and Strategies. 1995. Available online: http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/research/pub/hispanic.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Romano, E.; De La Rosa, M.; Sanchez, M.; Babino, R.; Taylor, E. Drinking and driving among documented and undocumented recent Latino immigrants in Miami Dade County, Florida. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 18, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraido-Lanza, A.F.; Echeverria, S.E.; Florez, K.R. Latino immigrants, acculturation, and health: Promising new directions in research. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2016, 37, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez Roux, A.; Mair, C. Neighborhoods and Health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karriker-Jaffe, K.J.; Zemore, S.E.; Mulia, N.; Jones-Webb, R.; Bond, J.; Greenfield, T.K. Neighborhood disadvantage and adult alcohol outcomes: Differential risk by race and gender. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2012, 73, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, M.; De La Rosa, M.; Blackson, T.C.; Rojas, P.; Li, T. Pre- to post-immigration alcohol use trajectories among recent Latino immigrants. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014, 28, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpiano, R.M. Toward a neighborhood resource-based theory of social capital for health: Can Bourdieu and sociology help? Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R. Social capital: Measurement and consequences. Isuma Can. J. Policy Res. 2001, 2, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano, R.M. Neighborhood social capital and adult health: An empirical test of a Bourdieu-based model. Health Place 2007, 13, 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W.; Earls, F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 1997, 277, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidman, E.; Yoshikawa, H.; Roberts, A.; Chesir-Teran, D.; Allen, L.; Friedman, J.L.; Aber, J.L. Structural and experiential neighborhood contexts, developmental stage, and antisocial behavior among urban adolescents in poverty. Dev. Psychopathol. 1998, 10, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worrall, J.L.; Els, N.; Piquero, A.R.; TenEyck, M. The moderating effects of informal social control in the sanctions-compliance nexus. Am. J. Crim. Justice 2014, 39, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitle, T.M.; Wahl, A.G.; Arando, E. Immigrant generation, selective acculturation, and alcohol use among Latina/o adolescents. Soc. Sci. Res. 2009, 38, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portes, A.; Rumbaut, R.G. Immigrant America: A Portrait, 3rd ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A.; Fernández-Kelly, P. No margin for error: Educational and occupational achievement among disadvantaged children of immigrants. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2008, 620, 12–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Greenman, E. The social context of assimilation: Testing implications of segmented assimilation theory. Soc. Sci. Res. 2011, 40, 965–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, J.W.; Sam, D.L.; John, W. Stress perspectives in acculturation. In The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.S.; Colby, S.M.; Rohsenow, D.J.; Lopez, S.R.; Hernandez, L.; Caetano, R. Acculturation stress and drinking problems among urban heavy drinking Latinos in the northeast. J. Ethn. Subst. Abuse 2013, 12, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinney, C.M.; Chartier, K.G.; Caetano, R.; Harris, T.R. Alcohol availability and neighborhood poverty and their relationship to binge drinking and related problems among drinkers in committed relationships. J. Interpers. Violence 2012, 27, 2703–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concha, M.; Sanchez, M.; De La Rosa, M.; Villar, M.E. A longitudinal study of social capital and acculturation-related stress among recent Latino immigrants in South Florida. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2013, 35, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendryx, M.; Ahern, M. Access to mental health services and health sector social capital. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2001, 28, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latkin, C.A.; Curry, A.D. Stressful neighborhoods and depression: A prospective study of the impact of neighborhood disorder. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2003, 44, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berke, E.M.; Tanski, S.E.; Demidenko, E.; Alford-Teaster, J.; Shi, X.; Sargent, J.D. Alcohol retail density and demographic predictors of health disparities: A geographic analysis. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1967–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, M.A.; Bustamante, A.V.; Ang, A. Perceived quality of care, receipt of preventive care, and usual source of health care among undocumented and other Latinos. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009, 24, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.C.; Mason, C.A.; Spokane, A.R.; Cruza-Guet, M.C.; Lopez, B.; Szapocznik, J. The relationship of neighborhood climate to perceived social support and mental health in older Hispanic immigrants in Miami, Florida. J. Aging Health 2009, 21, 431–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viruell-Fuentes, E.A.; Schulz, A.J. Toward a dynamic conceptualization of social ties and context: Implications for understanding immigrant and Latino health. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 2167–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, C.; Harter, S.L. Examining the impact of acculturative stress on body image disturbance among Hispanic college students. Cultur. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2012, 18, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchet, K. How to facilitate social contagion? Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2013, 1, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano, M.; Sanchez, M.; De La Rosa, M.; Kanamori, M.J.; Trepka, M.; Sheehan, D.M.; Huang, H.; Rojas, P.; Auf, R.; Dillon, F.R. Immigration stress and alcohol use severity among recent adult Hispanic immigrants: testing the moderating effects of gender and immigration status. J. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potochnick, S.R.; Perreira, K.M. Depression and anxiety among first-generation immigrant Latino youth: Key correlates and implications for future research. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2010, 198, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Suh, W.; Kim, S.; Gopalan, H. Coping strategies to manage acculturative stress: Meaningful activity participation, social support, and positive emotion among Korean immigrant adolescents in the USA. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2012, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; McBride, K.; Kak, V. Role of social support in examining acculturative stress and psychological distress among Asian American immigrants and three sub-groups: Results from NLAAS. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 1597–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sam, D.L.; Berry, J.W. Acculturation: When individuals and groups of different cultural backgrounds meet. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara, M.; Gamboa, C.; Kahramanian, M.I.; Morales, L.S.; Hayes Bautista, D.E. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: A review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2005, 26, 367–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Fact Sheet: Alcohol and the Hispanic Community. 2013. Available online: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/HispanicFact/hispanicFact.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, M.J.; Marsiglia, F.F.; Ayers, S.L.; Nuno-Gutierrez, B. Substance use, religion, and Mexican adolescent intentions to use drugs. In Public Health, Social Work, and Health Inequalities; Friedman, B.D., Merrick, J., Eds.; Nova Science: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, E.; Voas, R.B.; Tippetts, A.S. Stop sign violations: The role of race and ethnicity on fatal crashes. J. Saf. Res. 2006, 37, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyrus, E.; Trepka, M.J.; Gollub, E.; Fennie, K.; Li, T.; Albatineh, A.N.; De La Rosa, M. Post-immigration changes in social capital and substance use among recent Latino immigrants in South Florida: Differences by documentation status. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, M.; Dillon, F.R.; De La Rosa, M. Impact of religious coping on the alcohol use and acculturative stress of recent Latino immigrants. J. Relig. Health 2015, 56, 1986–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillon, F.R.; De La Rosa, M.R.; Sanchez, M.; Schwartz, S.J. Pre-immigration family cohesion and drug/alcohol abuse recent Latino immigrants. Fam. J. 2013, 20, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salganik, M.J.; Heckathorn, D.D. Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociol. Methodol. 2003, 34, 193–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Rosa, M.; Babino, R.; Rosario, A.; Martinez, N.V.; Aijaz, L. Challenges and strategies in recruiting, interviewing, & retaining recent Latino Immigrants in substance abuse and HIV. Am. J. Addict. 2012, 21, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Babor, T.F.; Biddle-Higgins, J.C.; Saunders, J.B.; Monteiro, M.G. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; Available online: http://www.talkingalcohol.com/files/pdfs/WHO_audit.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2016).

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. 2008 National Survey of Drinking and Driving Attitudes and Behaviors. Available online: http://www.nhtsa.gov/Driving+Safety/Occupant+Protection/2008+National+Survey+of+Drinking+and+Driving+Attitudes+and+Behaviors (accessed on 12 September 2016).

- Lengyel, T.E.; Thompson, C.; Niesl, P.J. Strength in Adversity: The Resourcefulness of American Families in Need; Family Service America, Inc.: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Shelbourne, C.D.; Stewart, A.L. The MOS Social Support Survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, R.C.; Padilla, A.M.; Salgado de Snyder, N. The Hispanic Stress Inventory: A culturally relevant approach to psychosocial assessment. Psychol. Assess. 1991, 3, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, C.G.; Finch, B.F.; Ryan, D.N.; Salinas, J.J. Religious involvement and depressive symptoms among Mexican-origin adults in California. J. Community Psychol. 2009, 37, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loury, S.; Kulbok, P. Correlates of alcohol and tobacco use among Mexican immigrants in rural North Carolina. Fam. Community Health 2007, 30, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behling, O.; Law, K.S. Translating Questionnaires and Other Research Instruments: Problems and Solutions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.; Fidell, L. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed.; Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Miami-Dade County Department of Planning and Zoning. Hispanics by Country of Origin in Miami-Dade County, Decennial Census 2000 and 2010. 2011. Available online: http://www.miamidade.gov/planning/library/reports/data-flash/2011-hispanics-by-origin.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Michael, Y.L.; Farquhar, S.A.; Wiggins, N.; Green, M.K. Findings from a community-based participatory prevention research intervention designed to increase social capital in Latino and African American communities. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2008, 10, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado, H.; Castañeda, S.F.; Talavera, G.A.; Lindsay, S.P. The role of social support and acculturative stress in health-related quality of life among day laborers in northern San Diego. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2012, 14, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, A.G.; Vega, W.A. Two different worlds: Acculturation stress and adaptation among Cuban and Nicaraguan families. J. Soc. Pers. Relationsh. 1996, 13, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Mapping the Latino Population, by State, County and City. Available online: http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/2013/08/latino_populations_in_the_states_counties_and_cities_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2016).

- Schwartz, S.J.; Unger, J.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Szapocznik, J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. Am. Psychol. 2010, 65, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepick, A.; Grenie, R.G.; Castro, M.; Dunn, M. This Land Is Our Land: Immigrants and Power in Miami; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alegria, M.; Page, J.B.; Hansen, H.; Cauce, A.M.; Obles, R.; Blanco, C.; Berry, P. Improving drug treatment services for Hispanics: Research gaps and scientific opportunities. Drug Depend. 2006, 84S, S76–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passel, J.S.; Cohn, D. Unauthorized Immigrant Populations: National and State Trends, 2010; Pew Hispanic Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Available online: http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/reports/133.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2016).

| Variable | n = 467 | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 212 | 45.4 | |

| Male | 255 | 54.6 | ||

| Documentation Status | Documented | 394 | 84.4 | |

| Undocumented | 73 | 15.6 | ||

| Education | Less than high school | 104 | 22.3 | |

| High school diploma | 234 | 50.1 | ||

| Some training/college | 114 | 24.4 | ||

| Bachelor’s (4–5 years college) | 12 | 2.6 | ||

| Post graduate/professional | 3 | 0.6 | ||

| Region of Origin | Cuba | 199 | 42.6 | |

| South America | 130 | 27.8 | ||

| Central America | 133 | 28.5 | ||

| Other Caribbean | 5 | 1.1 | ||

| DUI Risk Behavior | Yes | 61 | 13.3 | |

| No | 398 | 86.7 | ||

| Mean (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||

| Age | 31.84 (4.97) | −0.24 | −1.14 | |

| Annual Income | $19,962.52 ($16,524.38) | 9.36 | 137.15 | |

| Neighborhood | Informal Social Control | 18.18 (4.63) | −0.86 | 0.97 |

| Social capital | 2.91 (2.70) | 2.50 | 7.28 | |

| Social Support | 3.73 (1.04) | −0.41 | −0.61 | |

| Acculturative Stress | 3.18 (3.77) | 2.44 | 6.10 | |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | DUI Risk Behavior | 1.00 | |||||||

| 2. | Informal Social Control | −0.08 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 3. | Social Capital | 0.06 | 0.14 ** | 1.00 | |||||

| 4. | Social Support | −0.17 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.11 * | 1.00 | ||||

| 5. | Acculturative Stress | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.22 ** | −0.08 | 1.00 | |||

| 6. | Gender | 0.04 | −0.10 * | −0.06 | −0.19 ** | −0.05 | 1.00 | ||

| 7. | Documentation Status | −0.00 | 0.20 ** | 0.02 | 0.23 ** | −0.04 | −0.14 ** | 1.00 | |

| 8. | Alcohol Use | 0.22 ** | −0.20 ** | 0.06 | −0.23 ** | 0.11 * | 0.25 ** | −0.13 ** | 1.00 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanchez, M.; Romano, E.; Dawson, C.; Huang, H.; Sneij, A.; Cyrus, E.; Rojas, P.; Cano, M.Á.; Brook, J.; De La Rosa, M. Drinking and Driving among Recent Latino Immigrants: The Impact of Neighborhoods and Social Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13111055

Sanchez M, Romano E, Dawson C, Huang H, Sneij A, Cyrus E, Rojas P, Cano MÁ, Brook J, De La Rosa M. Drinking and Driving among Recent Latino Immigrants: The Impact of Neighborhoods and Social Support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2016; 13(11):1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13111055

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanchez, Mariana, Eduardo Romano, Christyl Dawson, Hui Huang, Alicia Sneij, Elena Cyrus, Patria Rojas, Miguel Ángel Cano, Judith Brook, and Mario De La Rosa. 2016. "Drinking and Driving among Recent Latino Immigrants: The Impact of Neighborhoods and Social Support" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 13, no. 11: 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13111055