Indigenous Values and Health Systems Stewardship in Circumpolar Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Background

1.2. On Values and Stewardship

1.3. Nordic and North American Values: Finland, Norway, the United States and Canada

1.4. Exploring Indigenous Values

Objective

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

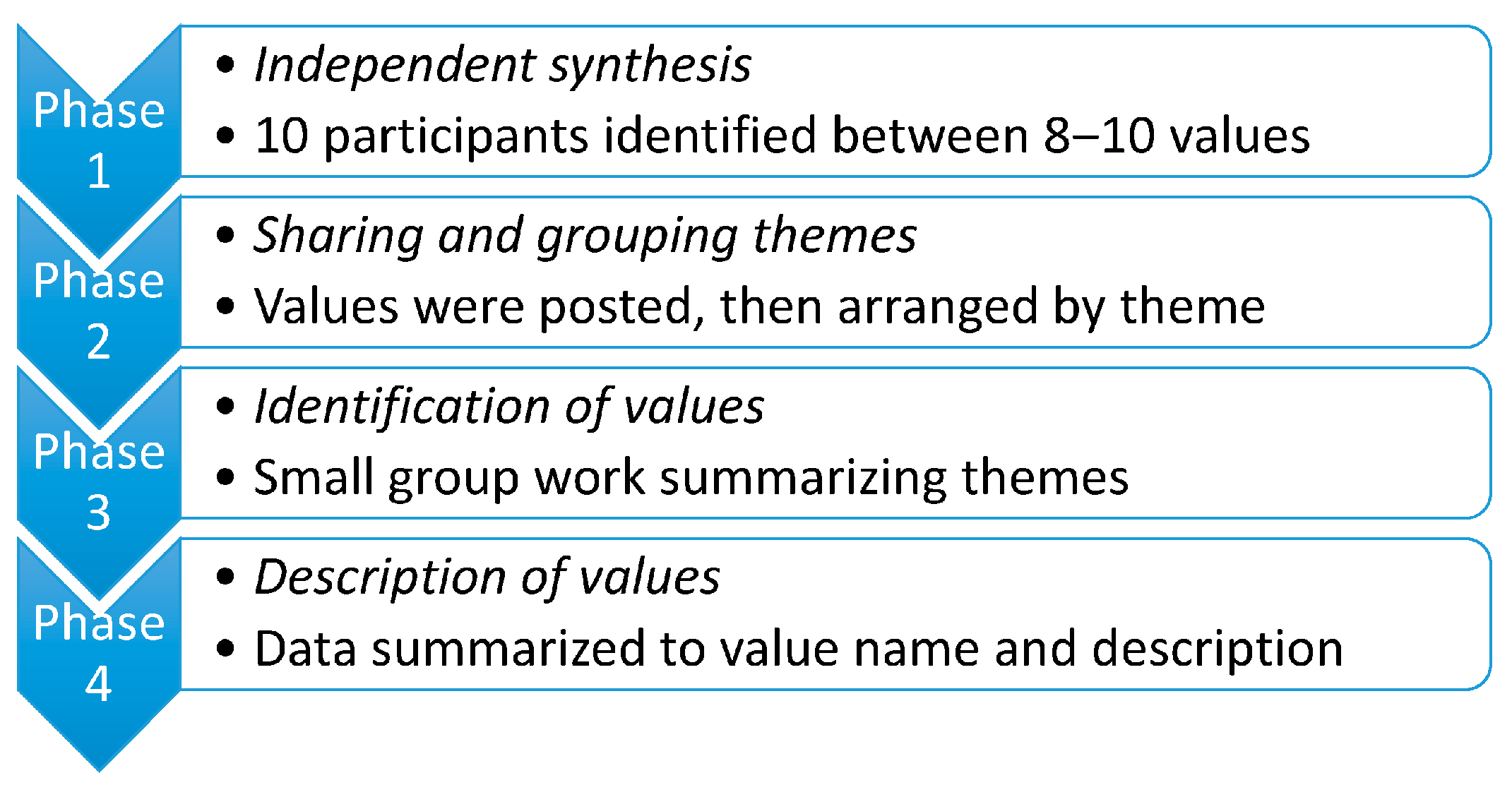

2.2. Process

3. Results

3.1. Humanity

3.2. Cultural Responsiveness

3.3. Teaching

3.4. Nourishment

3.5. Community Voice

3.6. Kinship

3.7. Respect

3.8. Holism

3.9. Empowerment

“When all that is put together—in my language simply we refer to this as “Dene Ch’anié” … It is descriptive of everything, our history, our spiritual, laws, environmental laws, political laws, economic laws, of how people are to live together, to interact. Protocols of living and families, communities and others. So for me, “Dene Ch’anié” is the best word I can use to describe this”.—workshop participant

4. Discussion

“For a person to be healthy, [he or she] must be adequately fed, be educated, have access to medical facilities, have access to spiritual comfort, live in a warm and comfortable house with clean water and safe sewage disposal, be secure in their cultural identity, have an opportunity to excel in a meaningful endeavour, and so on. These are not separate needs; they are all aspects of a whole”.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary File 1Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Phase | Values | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teachings | Cultural Responsiveness | Respect | Community Voice | Holism | Kinship | Empowerment | Nourishment | Humanity | |

| Phase 1 & 2 | |||||||||

| Values from Independent synthesis | Learn and do what you lean = teach Education and training Indigenous context in the education system Capacity building Traditions | Language and communication Indigenous knowledge/understanding Knowledge All things are connected Traditions Language Protocols Communication Traditional Knowledge | Understanding respect for different world view(s) Respect Reciprocity Reciprocity Honor the elders Honour Respect to culture Show respect to others Sacred | Boundaries Empowerment Resurgence of traditional values + way Sovereignty Place/land History Life Traditional Knowledge decolonization ties to homeland Time vs. timelessness | “Circle” Holistic Holistic perspectives Diversity Diversity interconnections | family family know who you come from Home, love and respect to land | short distance to hospital/health care co-ordinate for the patient not the system patient in centrum “situated response” process that respects culture/spirit and relations availability lifespan perspective access community driven | Food/sharing nourishment water housing traditional medicines livelihood environment connection | care acceptance sympathy/empathy have patience together emphathy see the humor/laugh/smile compassion pray for guidance listening love take care of others caring responsibility live carefully patience respect share what you have sensitivity accept life as it occurs |

| Phase 3 | |||||||||

| Group work summariaing themes | |||||||||

| Group 1 | Collaboration through indigenous knowledge transmission and knowledge receipt to achieve continuity in health and/or shared outcomes | Processes that must be reconceived to conduct community values centered health care | Manner in which interpersonal and community to community interactions should take place in | Historical legacies influence community conception of health, power relationships in health systems, and recognizes/leverages indigenous knowledge and the significance of forbearance in indigenous culture(s) | Recognition of place in the continuity of the cosmos, including space, time, place and purpose. Includes conception of distinctive roles, responsibilities, and restrictions/possibilities. | Community members’ shared histories, experiences, language(s), economy/trades which shape how we conceive health, experience health care, develop trust in healthcare systems, and interact with western medical systems. | “Community driven health care” The traditional and contemporary values of the community (ies) drive design, processes, and delivery of health care. | Structural and systematic influences on health and wellbeing with locus of control varying due to sociopolitical climate | Self-regulation concepts/Series of beliefs (mindset, spirituality) conducive to or complementary to a wholesome/full life |

| Group 2 | High quality culture sensitive health care services in own langauge | Respect of traditions, traditional knowledge and traditional healing methods | Established (by indigenous peoples) community care based on the needs, way of thinking, holistic perspective, of the indigenous peoples (instead of “translating” the systems of majorities to an indigenous language) | “circle” biopsychosocial | FOOD, local traditional food and nourishment | ||||

| Group 3 | shared research, self-reflection for person doing the work, collaboration, cooperativeness | +Active listening +trust. Respect embraces sensitivity and transparency and consensus | Preserving dignity, responsible, informed decisions that promote autonomy and independence | Maintenance of quality of our mental physical emotional spiritual life; we‘re in our highest functioning way | Sustainability, wise use of resources, equity in distribution and access to those resources | Humanitarian way of doing things; this value is foundational to many of the other ways | |||

| Group 4 | Traditional teachings have a central place in education and training of caregivers and health authorities; must look at spiritual and environment Laws → natural order Teaching must have a holistic view which must be shared with people who work in the field of health Interconnectedness must be part of the health system, health policy, and health directives | Protocols and clear communication need to be addressed, whether the protocols come from traditional knowledge or from language | Mutual respect (“two-way street”) | See holism | When people have a stable place they know their history tied to land and home, sense of tradition and values. They understand their place on the land. They understand their boundaries [physical boundaries tied to land] à empowerment [being rooted in own land and understanding how others fit in]. People with a sense of worth. Having this knowledge can lead to decolonization. Sense of empowerment and sovereignty can then emerge [ß has led into OURS] | Home, respect for the land. Family must know who you are related to, sense of extended family, must know where they came from and their place in the family. Everyone has a gift that they contribute to their family (unique contribution). The whole family must know their identity.Important to see family as sacred, see sacredness of families as en entity. Worldview must be reflective and respect differences within a family, between families, within and between communities | Services must be available, all must have access to hospitals and health centers. People in communities must have say in what services are provided at the community level | Water is essential to the health of people, whether living on water or land. Nourishment, food security, sharing of food;—all must have their place in hospitals and health authorities for people to access in order to maintain balanced health | humans struggle to strive for peace; conflict has always been a problem Often in cross-cultural situations need time to build trust—for wellbeing of both parties |

| (emphasising interdepence) When everything is said and done, it’s all about diverse communities and their interdependence | |||||||||

| Phase 4 | |||||||||

| Description of values | Traditional teachings have a central place in the education and training of caregivers and other people who work in health systems. Supporting cultural sensitivity by promoting a knowledge exchange among healthcare workers, researchers, and communities that incorporates a holistic view of the interconnectedness of traditional, spiritual, and environmental laws and an understanding of the natural order. | Having processes and protocols in place that focus healthcare on community values and culture, drawing on Indigenous/traditional knowledge, local languages, and styles of communication. | The manner in which interpersonal and community-to-community interactions should take place. Mutual respect for differences within and between families and communities. Respect of traditions, traditional knowledge, and traditional healing methods. Respect through active listening, trust, sensitivity, transparency, and consensus. | The traditional and contemporary values of the community drive the design, processes, and delivery of healthcare. Community members’ shared histories, experiences, language(s), and economy/trades shape how they conceive of health, experience healthcare, develop trust in healthcare systems, and interact with Western medical systems. Access to quality healthcare for all members of the community. | Having a holistic view of a person’s ties to land, home, traditions, values, distinctive roles and responsibilities, and boundaries/possibilities. Recognizing one’s place in the continuity of space, time, location, and purpose. Interconnections between the quality of our mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual lives. | Family as an expanded network of kinship associations. Family is sacred and gives a sense of place and origin. Recognizing each person’s unique contribution to family in the context of home and the land. | Promoting the sense of worth and empowerment of individuals, families, and communities as derived from understanding one’s place in the natural order and one’s ties to land and tradition. Establishing community care based on the needs, ways of thinking, and holistic perspectives of Indigenous peoples to preserve dignity and support. Informed decisions promote autonomy and independence. | Recognizing the importance of water and food as nourishment to achieve balanced health. Emphasizing local/traditional food and the sharing of food, and recognizing the need to use resources wisely and to ensure equitable access. | Emphasizing the fundamentality of relationships between human beings. Recognizing aspects of those relationships, including empathy, sensitivity, respect, and care, that sustain a wholesome life, build trust, and bridge conflict in cross-cultural settings. |

References

- Young, T.; Chatwood, S. Health care in the north: What Canada can learn from its circumpolar neighbours. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2011, 183, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The High North. Vision and Strategies; Meld. St. 7 (2011–2012) Report to the Storting (White Paper); Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Oslo, Norway, 2012.

- Government of Canada. Canada’s Northern Strategy Our North, Our Heritage, Our Future; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2009.

- The White House. National Strategy for the Arctic Region; The White House: Washington, WA, USA, 2013.

- Prime Ministers Office. Finland’s Strategy for the Arctic Region 2013; Government Resolution on 23 August 2013; Prime Ministers Office: Helsinki, Finland, 2013.

- Heininen, L.; Nicol, H.N. The Importance of Northern Dimension Foreign Policies in the Geopolitics of the Circumpolar North. Geopolitics 2007, 12, 133–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatwood, S.; Bjerregaard, P.; Young, T.K. Global health—A circumpolar perspective. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1246–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatwood, S.; Parkinson, A.; Johnson, R. Circumpolar health collaborations: A description of players and a call for further dialogue. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2011, 70, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkinson, A.J. Improving human health in the Arctic: The expanding role of the Arctic Council’s Sustainable Development Working Group. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2010, 69, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, J.D.; Berrang-Ford, L.; King, M.; Furgal, C. Vulnerability of Aboriginal health systems in Canada to climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A.; Maslin, M.; Montgomery, H.; Johnson, A.M.; Ekins, P. Global health and climate change: Moving from denial and catastrophic fatalism to positive action. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2011, 369, 1866–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, A.; Abbas, M.; Allen, A.; Ball, S.; Bell, S.; Bellamy, R.; Friel, S.; Groce, N.; Johnson, A.; Kett, M.; et al. Lancet and the University College London Institute for Global Health Commission. Managing the Health Effects of Climate Change. Lancet 2009, 373, 1693–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, A. Sustainable Development, Climate Change and Human Health in the Arctic. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2010, 69, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjerregaard, P. The Arctic health declaration. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2011, 70, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inuit Circumpolar Council. Kitigaaryuit Declaration; Inuit Circumpolar Council: Inuvik, NT, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chatwood, S.; Bytautas, J.; Darychuk, A.; Bjerregaard, P.; Brown, A.; Cole, D.; Hu, H.; Jong, M.; King, M.; Kvernmo, S.; et al. Approaching a collaborative research agenda for health systems performance in circumpolar regions. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2013, 72, 21474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Romanow, R. Building on Values. The Future of Health Care in Canada; Final Report; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2002.

- Turi, A.L.; Bals, M.; Skre, I.B.; Kvernmo, S. Health service use in indigenous Sami and non-indigenous youth in North Norway: A population based survey. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krümmel, E. The circumpolar Inuit health summit: A summary. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2009, 68, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coburn, V. Multiculturalism Policy Index: Indigenous Peoples; Paper Prepared as Part of Multiculturalism Policy Index Project; Queens School of Policy Studies: Kingston, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Press Secretary. Executive Order-Establishing the White House Council on Native American Affairs; The White House: Washington, WA, USA, 2013.

- Government of Canada; Right Honourable Stephen Harper; Prime Minister of Canada. Statement of Apology–To Former Students of Indian Residential Schools; Prime Minister of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2008.

- Mellgren, D. King Apologized to Samis; Associated Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Available online: www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2017).

- O’Cathain, A.; Murphy, E.; Nicholl, J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ 2010, 341, 4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Members of the National Forum on Health. Canada Health Action: Building on the Legacy; Synthesis Reports and Issues Papers; Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1997; Volume 2.

- Marmor, T.; Okma, K.G.; Latham, S. National values, institutions and health policies: Shat do they imply for medicare. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, P.; Egger, D.; Davies, P.; Mechbal, A. Towards Better Stewardhip: Concepts and Critical Issues. In Health Systems Performance Assessement Debates, Methods and Empiricism; Murray, C., Evans, D., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; pp. 298–300. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2000: Improving Health System Performance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Veillard, J.H.; Brown, A.D.; Baris, E.; Permanand, G.; Klazinga, N.S. Health system stewardship of national health ministries in the WHO European region: Concepts, functions and assessment framework. Health Policy 2011, 103, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltman, R.B.; Ferroussier-Davis, O. The concept of stewardship in health policy. Special theme—Health systems. Bull. World Health Organ. 2000, 78, 6. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Program. Governance for Sustainable Human Development. A UNDP Policy Document; United Nations Development Program: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, T. American values and health care reform. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council. Council conclusions on common values and principles in Eurporan union health systems. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, 146, 372. [Google Scholar]

- Snowdon, A.; Schnarr, K.; Hussein, A.; Alessi, C. Measuring what matters. In The Cost vs. Values of Health Care; Ivey International Centre for Health Innovation: London, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. The New European Policy for Health-Health 2020: Vision, Values, Main Directions and Approaches; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The Tallinn Charter: Health Systems for Health and Wealth; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, S. Law and the Public’s Health. Public Health Reports. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3743291/ (accessed on 26 November 2017).

- Health Canada. Canada Health Act Annual Report 2012–2013; Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013.

- Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services. National Health Plan for Norway; The Sorting: Oslo, Norway, 2006.

- Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. No. 1326/2010 Health Care Act; Ministry of Social Affairs and Health: Helsinki, Finland, 2010.

- Ministry of Social Affairs and Health; National Advisory Board on Health Care Ethics (ETENE). Equity and Human Dignitiy in Health Care in Finland; Ministry of Social Affairs and Health: Helsinki, Finland, 2001.

- Koskinen, S.; Aromaa, A.; Huttunen, J.; Teperi, J. Health in Finland; Finland Ministry of Social Affairs; National Public Health Institute KTL; National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health STAKES; Ministry of Social Affairs and Health: Helsinki, Finland, 2006.

- Health Canada. Royal Commission on Health Services (Hall Commission); Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1964; Volume 1.

- Health Canada. Canada Health Act; R.S.C., 1985, c. C-6; Minister of Justice: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015.

- Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF). Provincial and Territorial Health System Priorities: An Enviornmental Scan; Canadian Health Services Research Foundation: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chatwood, S.; Paulette, F.; Baker, R.; Eriksen, A.; Hansen, K.L.; Eriksen, H.; Hiratsuka, V.; Lavoie, J.; Lou, W.; Mauro, I.; et al. Approaching Etuaptmumk-introducing a consensus-based mixed method for health services research. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2015, 74, 27438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van de Ven, A.; Delbecq, A. The Nominal Group as a Research Instrument for Exploratory Health Studies. Am. J. Public Health 1972, 62, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mauro, I.; Beattie, H. Indigenous Health Values Workshop. Available online: http://www.ichr.ca/research/exploring-the-values-and-context-for-health-systems-in-an-indigenous-context/ (accessed on 26 November 2017).

- Jones, J.; Hunter, D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 1995, 311, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottlieb, K.; Sylvester, I.; Eby, D. Transforming your practice: What matters most. Fam. Pract. Manag. 2008, 15, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gaski, M.; Abelsen, B.; Hasvold, T. Forty years of allocated seats for Sami medical students-has preferential admission worked? Rural Remote Health 2008, 8, 845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yukon Hospital Corporation. Yukon first nations dietetic internship program 2013/14. In Building Nutrition Capacity in First Nations and Northern Communities; Yukon Hospital Corporation: Whitehorse, YT, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Epoo, B.; Stonier, J.; Van Wagner, V.; Harney, E. Learning midwifery in Nunavik: Community-based education for Inuit midwives. Pimatisiwin 2012, 10, 283. [Google Scholar]

- Arnakak, J. Incorporation of Inuit Qaujimanituqangit, or Inuit Traditional Knowledge, into The Government of Nunavut. J. Aborig. Econ. Dev. 2002, 3, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton Territorial Health Authority. Annual Report. Your Hospital-Our Story; Stanton Territorial Health Authority: Yellowknife, NT, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Nunavut. Consolidation of Midwifery Profession Act; S.Nu. 2008, c.18; Government of Nunavut: Iqaluit, NU, Canada, 2008.

- Architects, N. A Villiage Leads a Nation; Southcentral Foundation; Primary Care Center II & III: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Laiti, T.; Sorbye, O.; Solbakk, T. “Meahcceterapiija”, Adapting family treatment to an Indigenous Sami population. Camping out with the family. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2013, 72, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Canada Communication Group. Report on the Royal Comission on Aboriginal People; Summary of Recommendations; Canada Communication Group: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Okma, K.G.H. How (Not) to Look At proposals to Reform Canadian Health Care; Policy Options: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Values or Goals That Represent Values | Health and Policy Forums | National Health Acts | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health 2020 [36] EU | Tallinn Charter WHO Europe [37] | Canada Romanow Proposed Health Covenant [17] | USA [33] | USA PPACA [38] | Canada Health Act [39] | Norway (National Health Care Services Plan) [40] | Finland Objectives (Health Care Act) [41] | |

| Values | ||||||||

| Justice and Fairness | X | X | ||||||

| Solidarity | X | X | ||||||

| Dignity | X | |||||||

| Non-discrimination | X | |||||||

| Liberty | X | |||||||

| Respectful | X | |||||||

| Goals representing undefined values | ||||||||

| Universality | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Equity (access and outcomes) | X | X | X | X | ||||

| The right to participate in decision-making or * (mutual responsibility and public input) | X | X | X * | X | ||||

| Accountability Or *(democracy and legitimacy) | X | X | X | X * | ||||

| Access to care (responsiveness) # | X | X # | X | X | ||||

| Client-orientation or * (stronger patient role) | X | X * | X | |||||

| Strengthen cooperation or * (cohesion and interaction) or # (expansion of clinical preventative care and community investments) | X # | X * | X | |||||

| Portability (proximity and security) * | X | X | X * | |||||

| Public Administration | X | X | ||||||

| Promote health and welfare (work and health) * | X * | X | ||||||

| Efficiency and Effectiveness (professionalism and quality) * | X | X * | ||||||

| Sustainability (value, quality, and efficiency) * | X | X * | ||||||

| Comprehensiveness | X | |||||||

| Transparency | X | X | ||||||

| Medical progress | X | |||||||

| Privacy | X | |||||||

| Physician Integrity | X | |||||||

| Reduce health inequalities | X | |||||||

| Ethical | X | |||||||

| Strengthen primary care access and preventative care | X | |||||||

| Values Identified in National Documents | Indigenous Values Identified by Consensus Process |

|---|---|

| Dignity (Health 2020)/Ethics (Romanow report) | Humanity |

| Liberty (USA)/Solidarity (Health 2020, Tallinn) | Community voice |

| Justice and Fairness (of health care insurance) (USA) | Empowerment |

| Respect (Romanow report) | Respect |

| Non-discrimination (Health 2020) | Cultural responsiveness |

| - | Teaching |

| - | Nourishment |

| - | Kinship |

| - | Holism |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chatwood, S.; Paulette, F.; Baker, G.R.; Eriksen, A.M.A.; Hansen, K.L.; Eriksen, H.; Hiratsuka, V.; Lavoie, J.; Lou, W.; Mauro, I.; et al. Indigenous Values and Health Systems Stewardship in Circumpolar Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121462

Chatwood S, Paulette F, Baker GR, Eriksen AMA, Hansen KL, Eriksen H, Hiratsuka V, Lavoie J, Lou W, Mauro I, et al. Indigenous Values and Health Systems Stewardship in Circumpolar Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017; 14(12):1462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121462

Chicago/Turabian StyleChatwood, Susan, Francois Paulette, G. Ross Baker, Astrid M. A. Eriksen, Ketil Lenert Hansen, Heidi Eriksen, Vanessa Hiratsuka, Josée Lavoie, Wendy Lou, Ian Mauro, and et al. 2017. "Indigenous Values and Health Systems Stewardship in Circumpolar Countries" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14, no. 12: 1462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121462