Regretting Ever Starting to Smoke: Results from a 2014 National Survey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Sample

2.2. Measures of Smoking

2.2.1. Regret

2.2.2. Intention to Quit

2.2.3. Perception of Harm from Smoking

2.2.4. Experiential Thinking in Decision to Smoke and Addiction Perception

2.2.5. Beliefs and Intentions during Smoking Initiation

2.2.6. Demographics

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Perception of Harm from Smoking

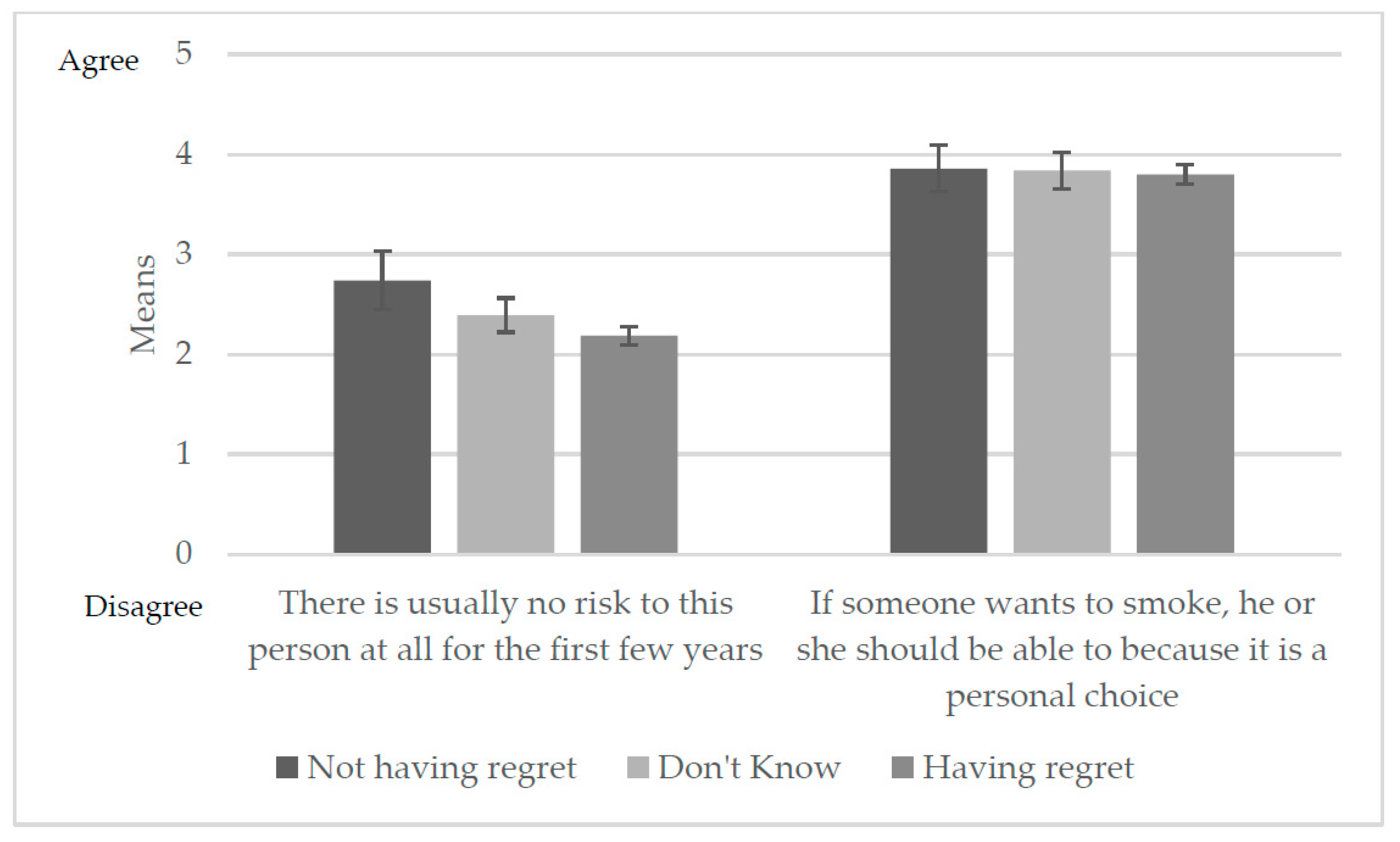

Relative Harm Perception

3.2. Experiential Thinking in the Decision to Smoke and Addiction Perceptions

3.3. Beliefs and Intentions during Smoking Initiation

3.4. Intention to Quit and Regret

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking-Attributable Mortality, Years of Potential Life Lost, and Productivity Losses—United States, 2000–2004; 0149-2195; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2008; pp. 1226–1228.

- U.S. Department of Health And Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking-50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking And Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014.

- Danaei, G.; Ding, E.L.; Mozaffarian, D.; Taylor, B.; Rehm, J.; Murray, C.J.L.; Ezzati, M. The preventable causes of death in the United States: Comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, P.; Ramasundarahettige, C.; Landsman, V.; Rostron, B.; Thun, M.; Anderson, R.N.; Mcafee, T.; Peto, R. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, G.T.; Hammond, D.; Laux, F.L.; Zanna, M.P.; Cummings, K.M.; Borland, R.; Ross, H. The near-universal experience of regret among smokers in four countries: Findings from the international tobacco control policy evaluation survey. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2004, 6, S341–S351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaloupka, F.J.; Warner, K.E.; Acemoglu, D.; Gruber, J.; Laux, F.; Max, W.; Newhouse, J.; Schelling, T.; Sindelar, J. An evaluation of the FDA’s analysis of the costs and benefits of the graphic warning label regulation. Tob. Control 2015, 24, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansone, N.; Fong, G.T.; Lee, W.B.; Laux, F.L.; Sirirassamee, B.; Seo, H.G.; Omar, M.; Jiang, Y. Comparing the experience of regret and its predictors among smokers in four Asian countries: Findings from the ITC surveys in Thailand, South Korea, Malaysia, and China. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013, 15, 1663–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balmford, J.; Borland, R. What does it mean to want to quit? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008, 27, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quitting Smoking among Adults—United States, 2001–2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011; pp. 1513–1519.

- Hughes, J.R. Motivating and helping smokers to stop smoking. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2003, 18, 1053–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1962; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Orcullo, D.J.C.; San, T.H. Understanding cognitive dissonance in smoking behaviour: A qualitative study. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanity 2016, 6, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.B.; Fong, G.T.; Zanna, M.P.; Omar, M.; Sirirassamee, B.; Borland, R. Regret and rationalization among smokers in Thailand and Malaysia: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Southeast Asia Survey. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slovic, P. Cigarette smokers: Rational actors or rational fools? In Smoking: Risk, Perception, and Policy; Slovic, P., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 97–124. [Google Scholar]

- Fotuhi, O.; Fong, G.T.; Zanna, M.P.; Borland, R.; Yong, H.H.; Cummings, K.M. Patterns of cognitive dissonance-reducing beliefs among smokers: A longitudinal analysis from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) four country survey. Tob. Control 2013, 22, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcmaster, C.; Lee, C. Cognitive dissonance in tobacco smokers. Addict. Behav. 1991, 16, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, A.J.; Mccaul, K.D.; Klein, W.M. Unrealistic optimism in smokers: Implications for smoking myth endorsement and self-protective motivation. J. Health Commun. 2006, 11, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakes, W.; Chapman, S.; Borland, R.; Balmford, J.; Trotter, L. “Bulletproof Skeptics in Life”s Jungle”: Which self-exempting beliefs about smoking most predict lack of progression towards quitting? Prev. Med. 2004, 39, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.D. Accuracy of smokers’ risk perceptions. Ann. Behav. Med. 1998, 20, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mccoy, S.B.; Gibbons, F.X.; Reis, T.J.; Gerrard, M.; Luus, C.A.; Sufka, A.V. Perceptions of smoking risk as a function of smoking status. J. Behav. Med. 1992, 15, 469–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, M.J.; Logel, C.; Fong, G.T.; Zanna, M.P.; Mcdonald, P.W. Perceived risk and quitting behaviors: Results from the ITC 4-country survey. Am. J. Health Behav. 2012, 36, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slovic, P. What does it mean to know a cumulative risk? Adolescents’ perceptions of short-term and long-term consequences of smoking. J. Behav. Decis. Making 2000, 13, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perception of risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.D. Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems. J. Behav. Med. 1982, 5, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.D. Why it won’t happen to me: Perceptions of risk factors and susceptibility. Health Psychol. 1984, 3, 431–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.D. Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems: Conclusions from a community-wide sample. J. Behav. Med. 1987, 10, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.D.; Marcus, S.E.; Moser, R.P. Smokers’ unrealistic optimism about their risk. Tob. Control 2005, 14, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slovic, P. Smoking: Risk, Perception, and Policy; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking And Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2012.

- Slovic, P. The “value” of smoking: An editorial. Health Risk Soc. 2012, 14, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, T.; Zeelenberg, M. Regret in decision making. Curr. Directions Psychol. Sci. 2002, 11, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Sandberg, T.; Mcmillan, B.; Higgins, A. Role of anticipated regret, intentions and intention stability in adolescent smoking initiation. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, R.J.; Thrasher, J.F.; Bansa-Travers, M. Exploring relationships among experience of regret, delay discounting, and worries about future effects of smoking among current smokers. Subst. Use Misuse 2016, 51, 1245–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GfK. Knowledgepanel® Design Summary; GfK: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, K.A.; Lerman, C.; Coddington, S.; Karelitz, J.L. Association of retrospective early smoking experiences with prospective sensitivity to nicotine via nasal spray in nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2008, 10, 1335–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomerleau, O.F.; Pomerleau, C.S.; Mehringer, A.M.; Snedecor, S.M.; Cameron, O.G. Validation of retrospective reports of early experiences with smoking. Addict. Behav. 2005, 30, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Respondent Characteristics | Overall | Smoker Self-Reported Regret Status (N = 1331) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1331 % (95% CI) | Not Having Regret n = 99; % (95% CI) | Don’t Know n = 247; % (95% CI) | Having Regret ** n = 985; % (95% CI) | |

| Total | - | 7.8 (6.10–9.50) | 20.7 (18.0–23.3) | 71.5 (68.6–74.4) |

| Sex * | ||||

| Male | 51.5 (48.4–54.7) | 63.5 (52.4–73.4) | 54.7 (47.4–61.8) | 49.3 (45.7–53.0) |

| Female | 48.5 (45.3–51.6) | 36.5 (26.6–47.7) | 45.3 (38.2–52.6) | 50.7 (47.0–54.4) |

| Age (years) * | ||||

| 18–34 years | 31.1 (28.0–34.2) | 30.3 (20.8–41.9) | 38.2 (31.1–45.8) | 29.1 (25.6–32.8) |

| 35–54 years | 41.1 (38.1–44.3) | 51.3 (40.0–62.4) | 37.1 (30.4–44.3) | 41.2 (37.6–44.9) |

| ≥55 years | 27.8 (25.3–30.5) | 18.4 (12.0–27.3) | 24.8 (19.5–30.9) | 29.7 (26.7–32.9) |

| Race/ethnicity * | ||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 61.1 (57.8–64.3) | 47.5 (36.6–58.7) | 56.3 (48.9–63.5) | 64.0 (60.2–67.6) |

| Other | 38.9 (35.8–42.2) | 52.5 (41.3–63.5) | 43.7 (36.5–51.1) | 36.0 (32.4–39.8) |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 57.6 (54.5–60.6) | 54.5 (43.2–65.2) | 63.3 (56.4–69.8) | 56.2 (52.6–59.8) |

| Some college | 32.3 (29.5–35.2) | 31.6 (22.7–42.2) | 28.0 (22.2–34.6) | 33.6 (30.3–37.0) |

| College degree + | 10.2 (8.6–12.0) | 13.9 (8.00–23.3) | 8.7 (5.80–12.9) | 10.2 (8.40–12.3) |

| Annual household income | ||||

| <$30,000 | 42.5 (39.4–45.7) | 45.4 (34.3–56.9) | 40.7 (33.7–48.1) | 42.8 (39.1–46.5) |

| $30,000–$60,000 | 30.0 (27.3–32.9) | 28.3 (19.6–39.1) | 33.9 (27.4–41.0) | 29.1 (26.0–32.4) |

| >$60,000 | 27.5 (24.8–30.2) | 26.3 (17.9–37.0) | 25.5 (19.8–32.1) | 28.1 (25.1–31.4) |

| Perceived health status | ||||

| Excellent/Very good | 32.3 (29.3–35.4) | 38.2 (27.3–50.4) | 33.0 (26.4–40.4) | 31.4 (28.1–35.0) |

| Good | 44.6 (41.4–47.8) | 35.9 (26.0–47.1) | 46.5 (39.4–53.8) | 44.9 (41.2–48.7) |

| Fair/Poor | 23.2 (20.5–26.0) | 26.0 (17.4–36.9) | 20.5 (15.1–27.2) | 23.7 (20.6–27.0) |

| Level of smoking * | ||||

| Non-Daily—Very light | 13.7 (11.6–16.1) | 20.7 (13.2–31.1) | 19.1 (13.7–26.0) | 11.4 (9.20–14.0) |

| Non-Daily—Light | 9.1 (7.5–11.1) | 5.1 (2.10–11.9) | 9.2 (5.80–14.3) | 9.6 (7.60–12.0) |

| Daily—Very light | 19.4 (16.9–22.1) | 27.8 (18.6–39.3) | 20.4 (15.0–27.1) | 18.1 (15.4–21.3) |

| Daily—Average | 22.7 (20.1–25.5) | 19.6 (12.2–30.0) | 25.0 (19.2–31.9) | 22.3 (19.4–25.6) |

| Daily—Heavy | 27.3 (24.6–30.1) | 20.8 (12.8–31.9) | 19.6 (14.6–25.9) | 30.2 (27.0–33.6) |

| Daily—Very heavy | 7.8 (6.40–9.60) | 6.1 (2.40–14.7) | 6.6 (4.40–10.0) | 8.4 (6.60–10.6) |

| Intention to quit * | ||||

| Quit in <1 month | 9.5 (7.80–11.4) | 5.6 (2.20–13.6) | 5.8 (3.20–10.3) | 11.0 (8.9–13.4) |

| Quit in 6 months to 1 year | 34.6 (31.7–37.6) | 12.2 (6.70–21.3) | 19.9 (14.6–26.5) | 41.3 (37.8–45.0) |

| Quit someday | 42.6 (39.4–45.8) | 40.0 (29.4–51.7) | 52.2 (44.9–59.3) | 40.1 (36.4–43.8) |

| Never quit | 13.4 (11.4–15.6) | 42.2 (31.5–53.7) | 22.2 (17.0–28.3) | 7.7 (6.00–9.70) |

| Attempted quitting in the past year * | ||||

| Yes | 38.2 (35.2–41.3) | 24.2 (15.9–35.1) | 21.2 (15.7–27.9) | 44.7 (41.0–48.3) |

| No | 61.8 (58.7–64.8) | 75.8 (64.9–84.2) | 78.8 (72.1–84.3) | 55.3 (51.7–59.0) |

| ** Having Regret vs. Not Having Regret aOR (95% CI) | Don’t Know vs. Not Having Regret aOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Perception of harm from smoking | ||

| Worry about getting lung cancer | 5.3 (3.4–8.30) | 2.4 (1.5–3.80) |

| Smoking every day can be risky for your health | 2.6 (1.9–3.40) | 1.3 (1.0–1.80) |

| Smoking only once in a while can be risky for your health | 1.9 (1.4–2.60) | 1.3 (0.9–1.80) |

| Relative harm perception | ||

| There is usually no risk at all for the first few years | 0.7 (0.6–0.80) | 0.8 (0.7–0.98) |

| If someone wants to smoke, he or she should be able to because it is a personal choice | 0.9 (0.8–1.10) | 1.0 (0.8–1.20) |

| Compared to others your age who currently smoke cigarettes, what do you think are your chances of being diagnosed with lung cancer during your lifetime? | 1.6 (1.3–2.20) | 1.2 (0.9–1.60) |

| Experiential thinking in decision to smoke and addiction perception | ||

| How much do you think about the health effects of smoking cigarettes now? | 8.0 (5.2–12.3) | 2.1 (1.3–3.20) |

| Do you consider yourself addicted to cigarettes? | 3.5 (2.4–5.20) | 1.5 (1.03–2.3) |

| Not Having Regret | Don’t Know | ** Having Regret | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| How much do you think about the health effects of smoking cigarettes now? * (n = 1279) | |||

| Not at all | 41.9 (31.0–53.6) | 20.0 (14.8–26.6) | 5.13 (3.70–7.10) |

| A little | 43.3 (32.6–54.6) | 65.0 (57.3–71.9) | 46.56 (42.9–50.3) |

| A lot | 14.9 (8.20–25.5) | 15.0 (10.0–21.8) | 48.32 (44.6–52.0) |

| Do you consider yourself addicted to cigarettes? * (n = 1286) | |||

| Not at all | 30.4 (21.2–41.6) | 21.2 (15.5–28.3) | 5.51 (4.00–7.60) |

| Yes, somewhat addicted | 45.1 (34.2–56.6) | 48.7 (41.0–56.4) | 44.82 (41.2–48.5) |

| Yes, very addicted | 24.5 (15.2–36.9) | 30.1 (23.5–37.7) | 49.68 (46.0–53.4) |

| Not Having Regret | Don’t Know | ** Having Regret | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n, % (95% CI) | n, % (95% CI) | n, % (95% CI) | |

| Thinking again about the first time you ever smoked a cigarette, did your smoking happen with much thought or without much thought? * (n = 1324) | |||

| With much thought | 26.6 (18.0–37.3) | 12.8 (8.70–18.4) | 10.6 (8.70–12.9) |

| Without much thought | 68.3 (57.3–77.6) | 62.2 (54.8–69.0) | 81.2 (78.1–83.9) |

| I don‘t know | 5.2 (2.20–11.7) | 25.1 (19.1–32.2) | 8.2 (6.30–10.7) |

| When you first started smoking cigarettes, did you think more about how smoking would affect your future health or about how you were trying something new and exciting? * (n = 1325) | |||

| Thought more about future health | 8.5 (3.88–18.2) | 5.5 (2.50–11.6) | 3.9 (2.60–6.00) |

| Thought more about trying something new and exciting | 26.7 (17.6–38.3) | 35.3 (28.6–42.6) | 43.0 (39.4–46.6) |

| I did not think about either of these | 64.7 (52.9–75.0) | 59.2 (51.8–66.3) | 53.1 (49.4–56.8) |

| When you first started smoking cigarettes, how long did you think you would continue to smoke? * (n = 1325) | |||

| Less than a year | 11.6 (6.10–20.9) | 12.3 (7.90–18.6) | 22.5 (19.4–25.9) |

| 1 year or more | 17.0 (10.3–26.7) | 7.1 (4.10–12.0) | 7.7 (5.90–9.90) |

| I didn‘t think about it | 62.4 (51.1–72.5) | 56.1 (48.7–63.2) | 58.2 (54.4–61.8) |

| I don‘t know | 9.0 (4.40–17.6) | 24.5 (18.7–31.5) | 11.7 (9.60–14.2) |

| ** Having Regret vs. Not Having Regret aOR (95% CI) | Don’t Know vs. Not Having Regret aOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Thinking again about the first time you ever smoked a cigarette, did your smoking happen with much thought or without much thought? | ||

| With much thought | ref | ref |

| Without much thought | 2.8 (1.7–4.7) | 2.1 (1.2–3.9) |

| I don’t know | 2.8 (1.1–7.3) | 8.1 (3.0–21.9) |

| When you first started smoking cigarettes, did you think more about how smoking would affect your future health or about how you were trying something new and exciting? | ||

| Thought more about future health | ref | ref |

| Thought more about trying something new and exciting | 2.8 (1.04–7.7) | 2.2 (0.7–7.3) |

| I did not think about either of these | 1.4 (0.65–3.8) | 1.9 (0.7–5.8) |

| When you first started smoking cigarettes, how long did you think you would continue to smoke? | ||

| Less than a year | ref | ref |

| 1 year or more | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | 0.4 (0.1–1.0) |

| I didn’t think about it | 0.5 (0.3–0.99) | 1.2 (0.5–2.6) |

| I don’t know | 0.7 (0.3–1.7) | 2.8 (1.0–7.8) |

| Level of smoking | ||

| Non-Daily—Very light | ref | ref |

| Non-Daily—Light | 2.6 (1.0–6.9) | 1.8 (0.6–5.2) |

| Daily—Very light | 1.1 (0.5–2.2) | 0.9 (0.4–1.9) |

| Daily—Average | 1.6 (0.8–3.3) | 1.2 (0.6–2.6) |

| Daily—Heavy | 2.1 (1.1–4.2) | 1.1 (0.5–2.2) |

| Daily—Very heavy | 2.5 (0.9–7.3) | 1.8 (0.6–5.7) |

| Intention to quit | ||

| Low vs. high | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) |

| Quit attempts | ||

| Yes vs. no | 2.9 (1.8–4.8) | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nayak, P.; Pechacek, T.F.; Slovic, P.; Eriksen, M.P. Regretting Ever Starting to Smoke: Results from a 2014 National Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14040390

Nayak P, Pechacek TF, Slovic P, Eriksen MP. Regretting Ever Starting to Smoke: Results from a 2014 National Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017; 14(4):390. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14040390

Chicago/Turabian StyleNayak, Pratibha, Terry F. Pechacek, Paul Slovic, and Michael P. Eriksen. 2017. "Regretting Ever Starting to Smoke: Results from a 2014 National Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14, no. 4: 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14040390