Impact of Interprofessional Relationships from Nurses’ Perspective on the Decision-Making Capacity of Patients in a Clinical Setting

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants and Research Context

2.3. Interviews with Nurses

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Research Limitations

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Castro Orellana, R. Ethics for a Face of Sand: Michel Foucault and the Care of Freedom. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The Use of Pleasures: Volume 2 of History of Sexuality; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1985; Available online: https://mvlindsey.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/hos-vol-2-foucault-1985.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2011).

- Schmid, W. In Search of a New Art of Living: The Question for the Foundation and the New Foundations of Ethics in Foucault; Pre-Textos: Valencia, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977; Harvester Press: Brighton, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The Archeology of Knowledge; Siglo Veintiuno: Mexico DF, Mexico, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Sauquillo, J. Michel Foucault: A Philosophy of Action; Centro de Estudios Constitucionales: Madrid, Spain, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Politics and ethics: An interview. In The Foucault Reader: An Introduction to Foucault’s Thought; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The birth of social medicine: Conference of the year 1974 at the University of Rio de Janeiro. Rev. Centroam. Cienc. Salud 1977, 6, 168–197. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Crisis of a model of medicine? Conference of the year 1974 at the University of Rio de Janeiro. Rev. Centroam. Cienc. Salud 1976, 3, 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. On the Genealogy of Ethics: Foucault and Ethics; Biblos: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, J. Patient participation: A review of the literature. J. Clin. Nurs. 1998, 7, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo Arellano, F.; Borja Cevallos, L.G.; Borja Cevallos, L.T.; Flores Boada, M.V.; Medina Dávalos, D.M. Research and Bioethics; Edimec: Quito, Ecuador, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuokkanen, L.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Power and empowerment in nursing: Three theoretical approaches. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 31, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury-Jones, C.; Sambrook, S.; Irvine, F. Power and empowerment in nursing: A fourth theoretical approach. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansson, A.; Foldevi, M.; Mattsson, B. Medical students’ attitudes toward collaboration between doctors and nurses—A comparison between two Swedish universities. J. Interprof. Care 2010, 24, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlay, L. Powerful relationship. Nurs. Manag. 2005, 12, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallet, C.E.; Austin, L. Community nurses’ perceptions of patient ‘compliance’ in wound care: A discourse analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 32, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottow, M.H. Comentários sobre Bioética, vulnerabilidade e proteção. In Poder e Injustiça; Garrafa, V., Pessini, L., Eds.; Loyola: São Paulo, Brazil, 2003. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman, S.; Frederickson, K.; Lundy, T. Using an electric model to educate students about cultural influences on the nurse-patient relationship. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2004, 25, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gilberg, T.P. Trust and managerialism: Exploring discourses of care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaramillo Echeverri, L.; Pinilla Zuluaga, C. Perception of the patient and their communicative relationship with the nursing staff. Index Enferm. 2004, 13, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Trojan, L.; Yonge, O. Developing trusting, caring relationships: Home care nurses and elderly clients. J. Adv. Nurs. 1993, 18, 1903–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, S. Power imbalance between nurses and patients: A potential inhibitor of partnership in care. J. Clin. Nurs. 2003, 12, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foucault, M. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archeology of Medical Look, 20th ed.; Siglo XXI: México DF, Mexico, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Las palabras y las cosas: Una arqueología de las ciencias humanas. In Words and Things: An Archeology of the Human Sciences; Siglo Veintiuno: México DF, Mexico, 1968. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The Order of Discourse; Fábula Tusquets: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, J.; Álvarez Uría, F. Michel Foucault; Power Strategies; Ediciones Paidós Ibérica: Barcelona, Spain, 1999; Available online: http://www.medicinayarte.com/img/foucault_estrategias_de_poder.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2009).

- Schön, D.A. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions; Jossey-Bass: SanFrancisco, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dingwall, R.; McIntosh, J. Reading in Sociology of Nursing; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, N.A. Opportunities and constraints of teamwork. J. Interprof. Care 1999, 13, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastaldo, D.; Holmes, D. Foucault and nursing: A history of the present. Nurs. Inq. 1999, 6, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foucault, M. Dialogue on Power: Aesthetics, Ethics and Hermeneutics. Essential Works—Volume III; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1999; Available online: https://es.slideshare.net/doctorcienciasgerenciales/foucault-michel-estetica-etica-y-hermeneutica (accessed on 12 May 2011).

- Lunardi, V.L.; Peter, E.; Gastaldo, D. Is the submission of nurses ethical? A reflection on power anorexia. Enfer. Clín. 2006, 16, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró Bonet, M. Why We Are as We Are: Continuities and Transformations of Discourses and Power Relations in the Construction of the Professional Identity of the Nurses in Spain (1956–1976); Universitat de les Illes Balears: Palma de Mallorca, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez García, M.; Suárez Ortega, M.; Manzano Soto, N. Gender stereotypes and values about work among Spanish students. Revis. de Educ. 2011, 355, 331–354. [Google Scholar]

- Little, M.; Jordens, C.F.C.; Sayers, E.J. Discourse communities and discourse of experience. Health 2003, 7, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elston, M.A. Medical work in America: Essays on health care. Sociology 1991, 25, 159–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.B. Clinical nurse specialist collaboration with physicians. Clin. Nurse Spec. 1990, 4, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schön, J.C.; Frost, R.; Chu, M. Shapes of completely wetted two-dimensional powder compacts for applications to sintering. J. Appl. Phys. 1992, 71, 32–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Tecnologías DEL Yo. Technologies of the Self; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Manias, E.; Street, A. Possibilities for critical social theory and Foucault’s work: A toolbox approach. Nurs. Inq. 2000, 7, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Peerson, A. Foucault and modern medicine. Nurs. Inq. 1995, 2, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foucault, M. History of Sexuality: The Will of Knowledge, 30th ed.; Siglo XXI: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Michel Foucault: Un Diálogo Sobre el Poder y Otras Conversaciones. In A Dialogue about the Power and Other Conversations; Morey, M., Ed.; Altaya: Barcelona, Spain, 1994; pp. 128–145. Available online: http://flacso-teoria-social-2013.wikispaces.com/file/view/Foucault_Michel-Un_dialogo_sobre_el_poder_y_otras_conversaciones.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2005).

- Björkdahl, A. Psyk-VIPS: Att Dokumentera Psykiatrisk Omvårdnad Enligt VIPS-Modellen; Studentlitteratur: Lenghth, Swedish, 1999; Available online: https://walaschaizarsa.firebaseapp.com/694931414308332.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2011).

- Ehnfors, M.; Enhrenberg, A. Rhorell-Ekstrand, I. The 25 VIPS-book. In A Research Based Model for Nursing Documentation in Patient Record. FoU 48; Värdförbundet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2000; Available online: https://www.ltu.se/cms_fs/1.48382!/file/thesis.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2013).

- Devereux, P.M. Essential elements of nurse-physician collaboration. J. Nurs. Adm. 1988, 11, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, L.; Tang, K.; Liu, Y. Consistency between preference and use of long-term care among caregivers of stroke survivors. Public Health Nurs. 1998, 15, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georges, J.M. An emerging discourse towards epistemic diversity in nursing. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2003, 26, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleuze, G. What is a device? In Michel Foucault, Filósofo. Michel Foucault, Philosopher; Balibar, E., Deleuze, G., Dreyfus, H., Eds.; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 1995; pp. 12–27. [Google Scholar]

- Larrosa, J. School, Power and Subjectivation; Editorial La Piqueta: Madrid, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cheek, J.; Porter, S. Reviewing Foucault: Possibilities and problems for nursing and health care. Nurs. Inq. 1997, 4, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, N. Justice Interrupts; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pinho, L.B. Meanings and perceptions about nursing care in the intensive care unit. Index Enferm. 2006, 15, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, R.; Manias, E. Polgase, A. Governing the surgical count through communication interactions: Implications for patient safety. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2006, 15, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benner, A.B. Physician and nurse relationships, a key to patient safety. J. Ky. Med. Assoc. 2007, 105, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zaforteza, C.; De Pedro, J.; Gastaldo, D. ¿Qué perspectivas tienen las enfermeras de unidades de cuidados intensivos de su relación con los familiares del paciente crítico? Enferm. Intensiv. 2003, 14, 109–119. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribb, A.; Entwistle, M.A. Shared decisión making: Trade-offs between narrower and broader conceptions. Health Expect 2011, 14, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gafni, A.; Charles, C. The physician-patient encounter: An agency relationship? In Shared Decision-Making in Healthcare: Achieving Evidence-Based Patient Choice, 2nd ed.; Edwards, A., Elwyn, G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, C.; Stoljar, N. Relational Autonomy: Feminist Perspectives on Autonomy, Agency and the Social Self; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, G.; Yarbrough, S.; Pang, K. The patient self-determination, act: 20 years revisited. J. Nurs. Law 2009, 13, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, C. Health Policy in Britain: The Politics and Organization of the NHS, 3rd ed.; Macmillan: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Beattie, A. Evaluation in community development for health: An opportunity for dialogue. Health Educ. J. 1995, 54, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, J.L. Desire to Care and the Will to Power: Teaching Nursing; Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Procacci, G. The Social Government. Foucault Effect; Feltrinelli: Milan, Italy, 1986; Available online: https://books.google.es/books?isbn=8884836816 (accessed on 3 April 2010).

- McCormick, K.; Logan, C.; Coenen, A. Vision for the Future: Health Informatics a Key to Evidence Based Future for Healthy People in a Healthy World; Premier Print: Auckland, New Zealand, 2000; pp. 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Green, S.D.; Thomas, J.D. Interdisciplinary collaboration and the electronic medical record. Pediatr. Nurs. 2008, 34, 225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Espin, C. A sculpture for living in. Inter. Des. 2002, 73, 164. [Google Scholar]

- Iliopoulou, K.K.; While, A.E. Professional autonomy and job satisfaction: Survey of critical care nurses in mainland Greece. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2520–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entwistle, V.A.; Carter, S.A.; Cribb, A. Supporting patient autonomy: The importance of clinician-patient relationships. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp, T.L.; Childress, J.F. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Molina Mula, J. Knowledge, Power and Culture of Self in the Construction of the Autonomy of the Patient in Decision Making. Relationship of the Nurse with the Patient, Family, Health Team and Health System; Universitat de les Illes Balears: Palma de Mallorca, Spain, 2013; Available online: http://www.tesisenred.net/bitstream/handle/10803/112120/tjmm1de1.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 23 March 2013).

- Taylor, C. Foucault, Freedom, Truth. Michel Foucault. Critical Readings; Éditions Universitaires: Bruxelles, Belgium, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Rochlitz, R. Aesthetics of Existence. Postconventional Moral and Power Theory. In Michel Foucault, Philosopher; Balibar, E., Deleuze, G., Dreyfus, H., Eds.; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hadot, P. Reflections on the Notion of Self Cultivation. In Michel Foucault, Philosopher; Balibar, E., Deleuze, G., Dreyfus, H., Eds.; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity; Taurus: Madrid, Spain, 1989. [Google Scholar]

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Surveillance | Strategy of control and production of behaviours that automatically occurs in the patient through an absolute coercive look exercised by professionals. The French philosopher calls this Panoptism. |

| The normalizing sanction | Infraction that sanctions anything that does not conform to the rule, to the indications of professionals, reducing the possibility of deviation or difference, hierarchizing the value of patients’ capacities, or tracing the limit of the abnormal. This technology forces homogeneity to reject everything that escapes the norm and labelling the patient as a “bad patient”. |

| The examination | Based on a system of objectivation that makes individuality enter a documentary field as if it were a describable and analysable unit, thus explaining the biomedical or biologicist model in health institutions. The hospital has required practices and operative speeches to make effective the production of disciplined individuals. |

| Code | Definition | Verbatim |

|---|---|---|

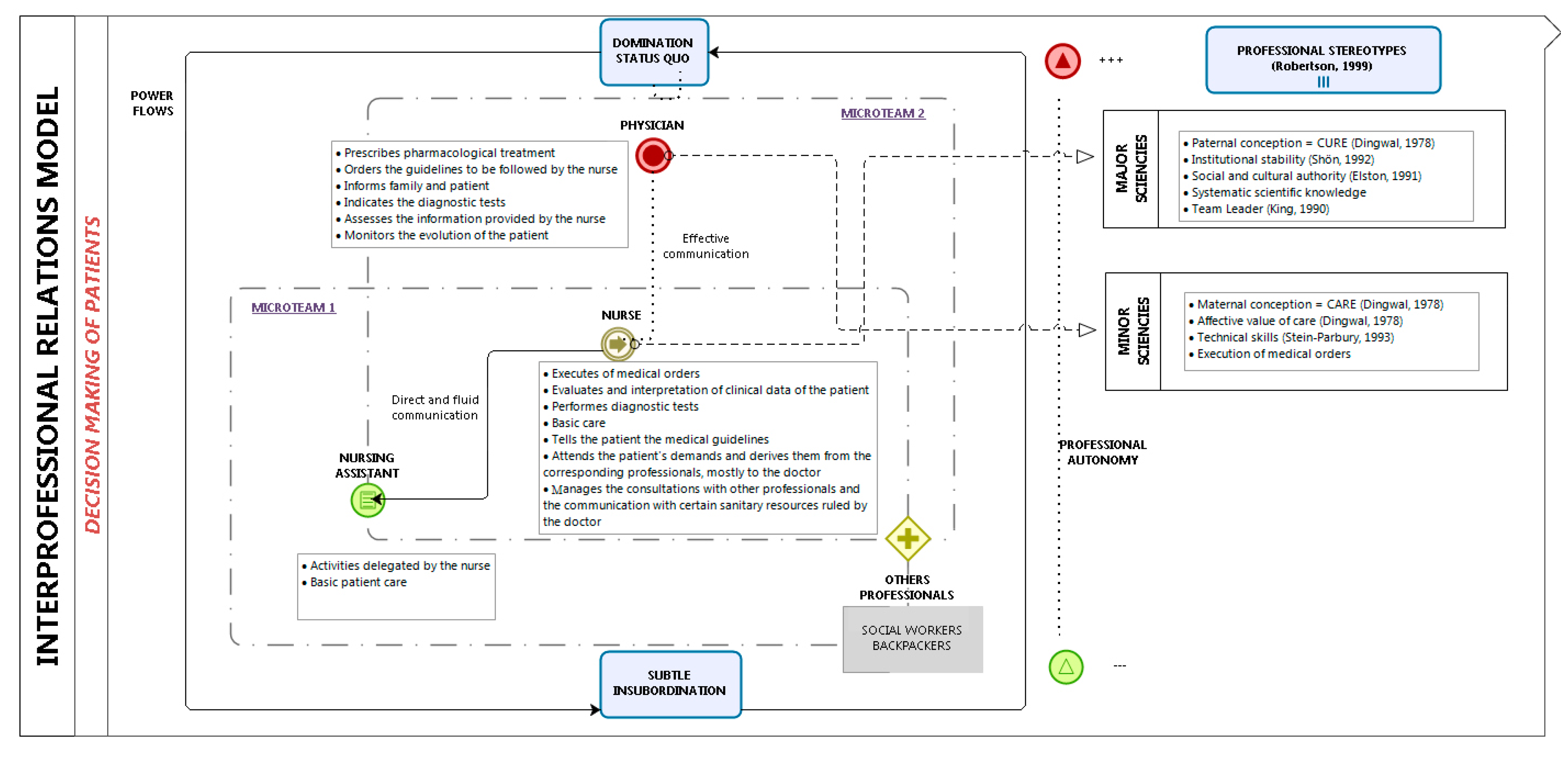

| Idealization of teamwork | The concept of teamwork stands out as diffuse, without clear characteristics. The nurses, rather than defining a joint effort with all team members, describe micro-teams. | E1: “In my unit, I think that many do not work in a team. I mean, we complain about each other, but, in the end, nobody does anything to improve teamwork…” |

| The doctor is considered the top person on the team. Medical practice is highlighted as a priority, relegating the other nursing activities. Decision-making within the team is attributed to the doctor. | E6: “That is ideal. The practice? In my service? We do not go with them. Here, everyone moves freely. I try to go with the oncologist, but I do not always succeed.” | |

| A leading role for nurses for better communication between team members is proposed as key to the team’s smooth operation. It is a theoretical work model that has not been achieved in hospital units. | E6: “What they told us in school. This would be ideal...previously they had a session where it was discussed; they spoke of the cases, the cases that are logged...the view of the nurse would be requested...and then, you, the doctor, nurse, would go to see the patient.” | |

| The nurse in the healthcare team | The doctor is identified as being responsible for providing information. The nurse expands the information due to the short amount of time the doctor spends with the patient. For nurses with more years of experience in the unit, greater concern about the patients’ wellbeing is observed in their discourse due to problems with team members. | E5: “…sometimes we even have to respond to things from the doctors, also, things to cover their backs, but there are things that the doctor has not informed us about or when they happen, or what it is called, or...the patient is well informed but...there are fewer questions.” |

| The nurse assumes a strong role of supervision and control of the proper functioning of the unit and patient care. All nurses share the idea of being a key element in the functioning of the unit. | E1: “The nurse does have an important role. Yes, because I think if it weren’t for the nurse, things would not work as well, I mean, because you’re attentive, everything else works because even if everyone does their part separately, it is the nurse who later does it all, who monitors the work of everyone else.” | |

| The doctor’s dependence dominates. Decision-making about the patient, even about basic care, follows the doctor’s indications. Major communication gaps occur between both professionals, causing conflicts with the patient. Nurses with more years of experience, although they assume their role as dependent on the doctor, exert power in a subtle manner. | E2: “The doctor is the one who makes medical decisions and, without them, we do nothing, right? But, because there is so little communication (laughs), in the end, what happens is that we are a bit lost.” | |

| Limitations on teamwork | There are not adequate communication channels between the doctor and the nurse, causing an increase in workload due to efforts to re-channel information between them. Notably, for nurses with more experience in the unit, poor communication with the doctor does not cause a reactive and frustrated attitude as it does with less experienced nurses, but they instead opt to resign and establish lines of communication with the doctor outside of protocol. | E1: “…often, after the doctor visits for a little bit, you have to call because you have a question...Then, of course, if the doctor talks to you and says look, I am going to ask for a radiograph or something, or I’ve changed the antibiotic to this, you would not have to call later…” |

| The nurse would much rather support the assistant, and the assistant would choose a more involved nurse in the delegated activities. | E10: “I would say that the assistants in my service could help with nursing a little more…” | |

| Professional experience, seniority, and experience level in the unit are sources of tension within the healthcare team. The rejection of newer professionals was noted, especially by nurses with more experience. Nurses with less experience in the unit define the older and more experienced nurses as being confined to historical practices and standards. | E2: “…The more senior you are, the tension you causes about small things...I guess they are like work habits that you have...The less time you have worked, the fewer customs you have stuck in your head, and then it affects you less.” | |

| Limited professional empathy for other professionals. The lack of consensus on care and the lack of nurse satisfaction in the service provided also appear to be factors that hinder teamwork. | E5: “They are good workers, yeah, very good, but they lack such training, they lack empathy with patients, the family, with their partners, and if a person doesn’t empathize there, they don’t empathize on the street, or at home, or anywhere else…” | |

| The workload results in few opportunities and spaces in which to work collectively. We perceive that a structural change in the organization would be required to create more available time. | E7: “…you want to do all the work, which is a lot, and sometimes you can’t, you don’t manage to, and that creates tension because of course we want to reach the end of the shift and leave everything perfect, and you can’t most times, and then this generates more work than the previous shift…” | |

| Professional stereotypes: expert doctor, obedient nurse, and submissive assistant | The nurse describes the doctor as a professional expert, upon whom they are dependent, and is sometimes considered to be outside of the team. This stereotype of the expert doctor, based on the biomedical model established in the healthcare system, is characterized by a lack of communication, limitations placed on nurses in making decisions under the doctor’s judgment, and limitations on the time spent by the doctor with the patient. | E1: “I always think the biggest expert is the doctor...Well, I think all of us because the doctor says one thing we’re going to do, we must do rinses or we should try to make postural changes, well, although the doctor says it, we all know what we need to do.” |

| The nurse has a submissive stereotype based on the hierarchical relationships of the doctor’s dominance in clinical practice, which means that the nurse assumes a series of delegated responsibilities and acts merely as executor of the doctor’s orders. | E2: “Then, comes the doctor and sees him for five minutes…The doctor is the one who makes medical decisions and, without them, we do nothing, right? But, because there is so little communication (laughs), in the end, what happens is that we are a bit lost.” | |

| The health care institution is referred to as an excessively hierarchical organization that distributes workloads and the ability to participate in the centre’s decision-making based on professional categories. This situation causes inflexible stereotypes that are resistant to change, and creates situations that limit the decision-making ability of patients. | E8: “…Sure, doctors get along with everyone, nurses get along with everyone except the doctors, the assistants get along with, well, get along with nurses well but better with the guards, so to speak, right? It depends on the categories, right?” | |

| Operation of micro- teams in the healthcare team | The micro-team, formed by the nurse and the doctor, is based on a relationship of trust, with large deficits in communication. The main axis is the doctor. The organization of the nurse’s work is determined by the doctor’s agenda and the performance of standard diagnostic tests. The doctor only recognizes basic care as being the nurse’s partial responsibility, as this is also susceptible to medical decisions in the case of complications. | E1: “During the morning shift, the doctor has to do consultations and he has very little time to see patients on the ground; then, they often have to trust what we say.” |

| Nurses consider the micro-team formed with the assistant to be fundamental. The relationship is based on trust and closeness. The goal is to share information on patient care, where the nurse’s perspective prevails. | E8: “When I begin the shift with the assistant I like to go over if there is something important that is not there because it can be there on the tray and maybe I think it’s their job and they will do it, but, as a human, they could forget…” | |

| The patient as a communication tool between team members | For fluidity in communication, it must come from the nurse and depends on the doctor’s attitude. A sense of resignation appears in the nurse if communication with the physician is insufficient.The nurse and the assistant have a more direct relationship. Communication flows are established during shift changes, in the patient rooms, and the nurse’s station.Between nurses, direct communication occurs, and they share information or concerns regarding patients. | E7: “There is very poor communication both by doctors to the patient and family as well as by the doctor to the nursing team, and, as a result, there are very noticeable failures because sometimes the patient knows things we do not know and we seem unprofessional…” E5: “…for example, I tell the assistant everything at the end of the shift. Sometimes she says, why are you telling me this? In case you want to know. And I tell her all changes and anything at the end of the…” |

| Impact of interprofessional relationships and teamwork on patient autonomy | Communication difficulties in the team cause communication with the patient and family to be poor and create confusion due to the lack of consensus among the professionals. | E3: “Well, it’s bad...Maybe with the way we work, we convey it to the patient, and the patient is not to blame for anything, but the patient perceives it, and it can create discomfort for the patient…” |

| The lack of teamwork causes patient discomfort and repetitive activities, as well as failures and errors. In cases of non-fatal errors, they respond with corporatism to avoid patient mistrust toward professionals. | E2: “It is not the same as going every man for himself; for example, the assistant does hygiene, leaves you the patient to cure the ulcer, you have to go by yourself...rather than everyone go together, you use three steps, and I think that affects the patient, clearly.” | |

| For the nurse to feel safe and supported, they need a competent work partner and to work in teams, or at least to collaborate. Without this relationship, the degree of professional satisfaction decreases and impacts the quality of patient care. | E2: “It is not the same as having a teammate that you know will support you, who will help and you feel safe because you don’t have a partner you have tension with, I suppose because then you feel insecure, you feel, I don’t know.” |

| Mechanisms of Disciplinary Power | Description | Impact on Patient Autonomy |

|---|---|---|

| Normalization strategies | Common definitions of objectives and procedures that manifest in how you should arrange and organize professional activity. Its purpose is for professionals to be included in and identified with certain standards, achieving conformity within a health structure. | Standardization strategies define what is normal or deviant, accepted or unacceptable, superior or inferior, good or bad, directly or indirectly affecting the decision-making capacity of patients. |

| Homogenization | The mechanism of power verified in this research that hinders the individuality and uniqueness of our patients. | Modelling a type of patient passivity, or what Foucault called passive subjectivity in relation to oneself, because the patient is guided and directed to take charge of a truth provided by professionals that is virtually assumed to be accepted. Truth is thus configured as an element of the genealogy of ethics. The truth is related to power and it carries mechanisms of submission. In addition, it has effects on the individuality of patients [50]. |

| Surveillance and control | Foucault [26] pointed out how, through vigilance, whether deliberate or not, practitioners exercise their systems of control over power and knowledge. | Determine the most strategic positions of those thought to be inferior, such as the position of the doctor on the nurse and the position on the patient. |

| Subjugation | Physical and symbolic strategies that involve the individual in such a way that their movements and rhythms respond and are subordinated to the needs of the disciplinary devices. The subjection of patients to certain guidelines, rules, or norms is fundamental for sustaining the power relations that govern the health institution [43]. | The strategies of subjugation to the patients observed are mechanisms of imposition, subjection, repression, oppression, and dogma. |

| The clinical view | Metaphor that Foucault used to refer to another power strategy where events are read, organized, and interpreted in an anatomical-clinical conception [24]. | Extrapolated to an everyday view that is inscribed in clinical context and is both an effect and supports certain practices and relationships with patients. |

| Control of spaces and the use of the times | The control of spaces is the distribution and allocation of patients and interprofessional relationships to certain spaces, often spaces of closure. For Foucault, both physical and symbolic spaces are a fundamental piece for the device of knowledge and power. | The use of time is a strategy of exercising power by fragmenting or dividing activities or tasks at fixed times and pre-established times, which becomes a new control device. |

| Rewards and sanctions | Are strategies through which the permanence of an order or a normative power is achieved. | The management of rewards and punishments or threats according to the consideration of good or bad patient are achieved some of the mechanisms discussed above and reflected in the results. |

| Authors | Criticism |

|---|---|

| Molina-Mula et al. [72] | The assertion that Foucault’s ethics is a return to the subject matter that is solved with a new ethical approach, as opposed to the theory of the constituent subject involving a new conception of subjectivity. |

| Taylor et al. [73] | Believes that Foucault silences the moral foundations of his theoretical options and does so because they are humanistic criteria that he himself has rejected. |

| Rochlitz et al. [74] | Points out that Foucault’s critical interventions are norm-bearers and virtually universalist, since they refer to a demand for autonomy of the person and opposition to unjust suffering. |

| Hadot et al. [75] | Focuses his criticism on the incorrect use of historical material, considering Foucault’s ethical proposal as a personal bet rather than a faithful reflection of ancient ethical experience. It also considers that the practice of self-care without universal criteria necessarily results in an elitist scepticism that only applies to a few. |

| Habermas et al. [76] | Discusses Foucault’s ethics based on considering the existence of a self-referentiality, and an absence of normative foundations that designs a political theory without justification, where the lack of response to the ultimate meaning of resistance condemns the proposal to an arbitrary decisionism. |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molina-Mula, J.; Gallo-Estrada, J.; Perelló-Campaner, C. Impact of Interprofessional Relationships from Nurses’ Perspective on the Decision-Making Capacity of Patients in a Clinical Setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010049

Molina-Mula J, Gallo-Estrada J, Perelló-Campaner C. Impact of Interprofessional Relationships from Nurses’ Perspective on the Decision-Making Capacity of Patients in a Clinical Setting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(1):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010049

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolina-Mula, Jesús, Julia Gallo-Estrada, and Catalina Perelló-Campaner. 2018. "Impact of Interprofessional Relationships from Nurses’ Perspective on the Decision-Making Capacity of Patients in a Clinical Setting" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 1: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010049