A Qualitative Exploration of the Role of Vape Shop Environments in Supporting Smoking Abstinence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Interview Sample, Recruitment, and Data Collection

2.2. Observation Sample, Recruitment and Data Collection

2.3. Analysis

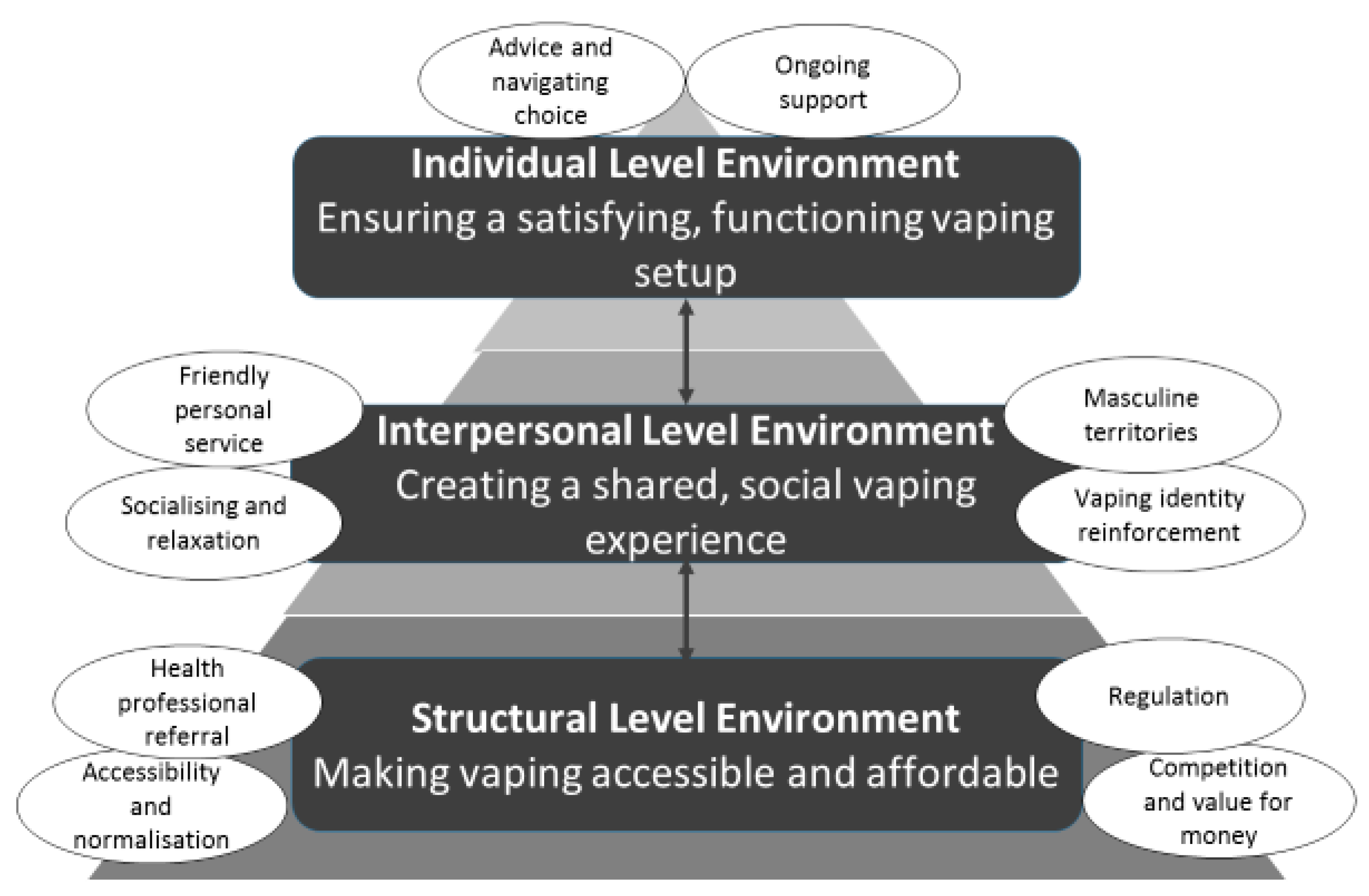

3. Results

3.1. Structural Level Environment—Making Vaping Accessible and Affordable

3.1.1. Accessibility and Normalization

I think you just see a lot of people using [e-cigarettes] now and there’s a lot of shops selling them. Certainly, in this area where I am, I only live in a small town, and there’s two shops that sell vaping supplies, so it’s really common. I went into a shop and you could actually try them there. So I tried them in the shop and then I bought one.(F40)

3.1.2. Competition and Value for Money

3.1.3. Regulation

3.1.4. Health Professional Referral

I said to [shop assistant] “look I’d seen the stop smoking service and that” and he said “have you seen <SSS advisor>?” and I was like “yes I have” and he said “yes she comes in here occasionally and she comes and she talks to us”. So it was almost like that she was taking the time to go out visit the retailers, find out what they were offering.(M46)

3.2. Interpersonal Environment—Creating a Shared Social Vaping Experience

3.2.1. Friendly Personal Service

3.2.2. Socialising and Relaxation

I’ve seen various vaping shops almost like trying to encourage your café atmosphere, none of them have succeeded. You walk in, you buy your liquid, you bugger off, you know. If someone was to set up sort of like a vaping type café, good luck to them, I’m not sure I would use it.(M53)

3.2.3. Vaping Identity Reinforcement

I opened the door [of the shop] and I just thought oh my god. They’ve got these big square things, the place is on fire! That don’t do nothing for me. I call them serious vapers. It might sound really silly, but I don’t know if they do it for different reasons, that’s how that comes across to me, that to sit there and [vaping noises] and then fill the room up with vape. It’s like going into a smoking room in an airport, which I used to find absolutely vile, and that’s what these shops have become.(F60)

3.2.4. Masculine Territories

I still find [shops] a little bit intimidating because [the shop] I go to they also sell like all the heavily modded tanks and batteries and stuff like that, so they are still a little bit kind of ‘boys clubby’ to me [...]. It’s blokes with their massive batteries and stuff like that, so I just kind of go in and go “right I want that liquid in that strength” and kind of take my leave.(F38)

3.3. Individual Level Environment—Ensuring a Satisfying and Functioning Vaping Setup

3.3.1. Advice and Navigating Choice

If you are serious about [quitting], I don’t think just buying, like I got the one from the factory shop. It was only like a tenner, it just wasn’t enough. I think you’ve probably got to get a bit of advice, cos it just didn’t work for me.(F29)

[Shop assistant] actually took the time to ask me some pertinent questions like “when you smoked your cigarettes, did you breathe direct to lung or did you breathe it into your mouth and then kind of breathe it down?” I quickly found out afterwards these questions are really quite important to getting the right sort of e-cigarette, because if you get the wrong it’s not going to satisfy the need and the chance are that you’re more likely to start smoking again.(M46)

I just found [shop assistant] to be incredibly helpful. She asked us more about our smoking history than actually I got asked at the smoking cessation clinic. She identified what it was we were smoking at the time, how much we were smoking, and then sort of looked at different strengths of the flavours what would suit us best. She recommended that I started on 18 mg strength nicotine liquid.(M44)

[The shop] were helpful in terms of finding something useable and reliable and had a big battery in it so you don’t have to constantly charge it, which is very important actually because I forget to charge it and then I’m in trouble because I don’t have my fall back.(M39)

They had a whole sort of display thing and they said “here’s all the different flavours that we sell, try some”. It was a case of just going through and trying and I just didn’t like the flavour of the tobacco ones, I just preferred the fruit flavours. Obviously when you stop smoking you start to get your taste back, so you could actually taste it more and more as time went on, so you were kind of “actually this is quite nice” and then you’d start to experiment with all the different flavours.(M46)

They didn’t offer much advice or information. They just had the e-cigarettes and the liquids and said this flavour’s nice, and this flavour’s nice, and there wasn’t really much conversation or information about it. It was very much like they just kind of wanted a sale on it.(F25)

3.3.2. Ongoing Support

I’m very reliant on going to the shop and going “help something has gone wrong”. They’ll just tut and go “you just do this like”. So I’ve got that reliance, I’ve almost got like a little help on hand.(F36a)

When they relapse find out why... “usually this is stress or because of drinking alcohol, sometimes because their coil started burning or liquid started leaking…. We can help with all those sorts of things”. I ask how he advises about stress or a night out, “that can be a good time to use the device more or maybe go up a level of nicotine”. He also tells me that “most people think their device is broken and they have relapsed, but if they bring it in and show us then we can fix it”.(Ob2)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Action on Smoking and Health (ASH). Facts at a Glance: Smoking and Disease. Available online: http://ash.org.uk/category/information-and-resources/fact-sheets/ (accessed on 22 November 2017).

- Etter, J.F.; Stapleton, J.A. Nicotine replacement therapy for long-term smoking cessation: A meta-analysis. Tobacco Control 2006, 15, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, R.; Beard, E.; Brown, J. Electronic Cigarettes in England—Latest Trends (2017 Q3). Available online: http://www.smokinginengland.info/sts-documents (accessed on 22 November 2017).

- Beard, E.; West, R.; Michie, S.; Brown, J. Association between electronic cigarette use and changes in quit attempts, success of quit attempts, use of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy, and use of stop smoking services in England: Time series analysis of population trends. Br. Med. J. 2016, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.; Beard, E.; Kotz, D.; Michie, S.; West, R. Real-world effectiveness of e-cigarettes when used to aid smoking cessation: A cross-sectional population study. Addiction. 2014, 109, 1531–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McRobbie, H.; Bullen, C.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Hajek, P. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation and reduction. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J. Learning to Smoke; Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2002; ISBN 10 0226359107. [Google Scholar]

- Notley, C.; Dawkins, L.; Ward, E.L.; Holland, R. Consumer experiences of quitting, switching, dual using, and ‘permissive lapse’ on the path to maintaining abstinence. In Proceedings of the 4th Global Forum on Nicotine, Warsaw, Poland, 15–17 June 2017; Available online: https://gfn.net.co/downloads/Presentations_2017_/Dr%20Caitlin%20Notley.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2017).

- Langley, T.; Bains, M. An insight into vape shops in the East Midlands. In Proceedings of the Cancer Research UK E-Cigarette Research Forum, London, UK, 23 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Farrimond, H. A typology of vaping: Identifying differing beliefs, motivations for use, identity and political interest amongst e-cigarette users. Int. J. Drug Policy 2017, 48, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, S.; Jakes, S. Nicotine and e-cigarettes: Rethinking addiction in the context of reduced harm. Int. J. Drug Policy 2017, 44, 84–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakes, S. Five E-Cigarette Summits on—What Are We Still Fighting about? In Proceedings of the E-Cigarette Summit, London, UK, 17 November 2017; Available online: https://nnalliance.org/blog/211-sarah-jakes-keynote-speech-at-the-e-cig-summit-2018 (accessed on 22 November 2017).

- Royal College of Physicians. Nicotine without Smoke: Tobacco Harm Reduction; Royal College of Physicians (RCP): London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/nicotine-without-smoke-tobacco-harm-reduction-0 (accessed on 22 November 2017).

- McNeil, A.; Brose, L.S.; Calder, R.; Hitchman, S.C.; Hajek, P.; McRobbie, H. E-Cigarettes: And Evidence Update; Public Health England: London, UK, 2015. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/457102/Ecigarettes_an_evidence_update_A_report_commissioned_by_Public_Health_England_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2017).

- The Tobacco Control Plan for England. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-tobacco-control-plan-for-england (accessed on 22 November 2017).

- McEwen, A.; McRobbie, H. Electronic Cigarettes: A Briefing to Stop Smoking Services; National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training: London, UK, 2016; Available online: http://www.ncsct.co.uk/usr/pub/Electronic_cigarettes._A_briefing_for_stop_smoking_services.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2017).

- Smoking in Pregnancy Challenge Group. Use of Electronic Cigarettes in Pregnancy: A Guide for Midwives and Other Healthcare Professionals. Available online: http://smokefreeaction.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/eCigSIP.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2017).

- Farrimond, H.; Abraham, C. E-cigarette friendly’ stop smoking services: The opportunities and barriers to incorporating e-cigarettes into health-care systems. In Proceedings of the 4th Global Forum on Nicotine, Warsaw, Poland, 15–17 June 2017; Available online: https://gfn.net.co/posters-2017/e-cigarette-friendly-stop-smoking-services-the-opportunities-and-barriers-to-incorporating-e-cigarettes-into-health-care-systems (accessed on 22 November 2017).

- Cancer Research UK and Action on Smoking and Health. Feeling the Heat: The Decline of Stop Smoking Services in England; CRUK: London, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/la_survey_report_2017.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2018).

- Moore, R.; Ross, L. Stop Smoking Services and e-cigarettes: Lessons from Leicester. Unpublished work. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stimson, G. A tale of two epidemics: Drugs harm reduction and tobacco harm reduction. In Proceedings of the London Drug & Alcohol Policy Forum, Guildhall, London, 14 April 2017; Available online: https://nicotinepolicy.net/documents/tale/Gerry%20Stimson%20-%20A%20tale%20of%20two%20epidemics.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2017).

- Action on Smoking and Health. Fact Sheet: Use of e-Cigarettes (Vaporisers) among Adults in Great Britain. Available online: http://ash.org.uk/media-and-news/press-releases-media-and-news/large-national-survey-finds-2-9-million-people-now-vape-in-britain-for-the-first-time-over-half-no-longer-smoke/ (accessed on 23 November 2017).

- Anastasopoulou, S. Almost 20% rise in vape store: UK Market Report. January 2018; ECigIntelligence. [Google Scholar]

- Independent Vape Trade Association. Available online: https://www.ibvta.org.uk/ (accessed on 23 November 2017).

- Electronic Cigarette Industry Trade Association. Available online: http://www.ecita.org.uk/ (accessed on 23 November 2017).

- Independent Vape Trade Association. Code of Conduct. Available online: https://www.ibvta.org.uk/join-us/code-of-conduct (accessed on 23 November 2017).

- New Nicotine Alliance. Assessing and Mitigating Unintended Consequences of Policies for Vapour Technologies and Other Low Risk Alternatives to Smoking. 2016. Available online: https://nnalliance.org/activities/consultations/114-nna-submits-comments-to-doh-on-unintended-consequences-of-vaping-policy (accessed on 14 December 2017).

- Independent British Vape Trade Association. The Battle for a Proportionate Regulatory Regime Continues. 2017. Available online: https://www.ibvta.org.uk/battle-proportionate-regulatory-regime-continues (accessed on 13 December 2017).

- Etter, J.; Farsalinos, K.; Hajek, P.; Le-Houezec, J.; McRobbie, H.; Bullen, C.; Kozlowski, L.T.; Nides, M.; Kouretas, D.; Polosa, R.; et al. Scientific Errors in the Tobacco Products Directive: A Letter Sent by Scientists to the European Union. 16 January 2016. Available online: http://www.ecigarette-research.com/web/index.php/2013-04-07-09-50-07/149-tpd-errors (accessed on 23 November 2017).

- Polosa, R.; Caponnetto, P.; Cibella, F.; Le-Houezec, J. Quit and Smoking Reduction Rates in Vape Shop Consumers: A Prospective 12-Month Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 3428–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, R.; Owen, L. Estimates of 52-Week Continuous Abstinence Rates Following Selected Smoking Cessation Interventions in England. Version 2. Available online: www.smokinginengland.info (accessed on 2 February 2018).

- Sussman, S.; Garcia, R.; Cruz, T.B.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Pentz, M.A.; Unger, J.B. Consumers’ perceptions of vape shops in Southern California: An analysis of online Yelp reviews. Tobacco Induced Dis. 2014, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notley, C.; Ward, E.; Dawkins, L.; Jakes, S.; Holland, R. Vaping as an alternative to smoking relapse following brief lapse. Unpublished work. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Allem, J.P.; Garcia, R.; Unger, J.B.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Sussman, S. Tobacco Attitudes and Behaviors of Vape Shop Retailers in Los Angeles. Am. J. Health Behav. 2015, 39, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheney, M.K.; Gowin, M.; Wann, T.F. Vapor Store Owner Beliefs and Messages to Customers. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2016, 18, 694–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, J.L.; Walker, K.L.; Sears, C.G.; Lee, A.S.; Smith, C.; Siu, A.; Keith, R.; Ridner, L. Vape Shop Employees: Public Health Advocates? Tobacco Prev. Cessat. 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burbank, A.D.; Thrul, J.; Ling, P.M. A Pilot Study of Retail ‘Vape Shops’ in the San Francisco Bay Area. Tobacco Prev. Cessat. 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sussman, S.; Allem, J.P.; Garcia, J.; Unger, J.B.; Cruz, T.B.; Garcia, R.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L. Who walks into vape shops in Southern California: A naturalistic observation of customers. Tobacco Induced Dis. 2016, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, G.; Unger, J.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Sussman, S. The associations between yelp online reviews and vape shops closing or remaining open one year later. Tobacco Prev. Cessat. 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sussman, S.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Garcia, R.; Barker, D.C.; Samet, J.M.; Leventhal, A.; Unger, J.B. Commentary: Forces That Drive the Vape Shop Industry and Implications for the Health Professions. Eval. Health Prof. 2016, 39, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E-cigarette Trajectories (ECtra): Real World Experiences of Using E-Cigarettes for Avoiding Relapse to Smoking: Success or Failure. A Qualitative Study. Ongoing September 2016–February 2018. Funded by Cancer Research UK. Available online: www.ecigsresearch.uea.ac.uk (accessed on 23 November 2017).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codes 1–3 in ONS Standard Occupational Classification Hierarchy. Available online: https://onsdigital.github.io/dp-classification-tools/standard-occupational-classification/ONS_SOC_hierarchy_view.html (accessed on 10 October 2017).

- Cancer Research, UK. Reasons Why Vaping Is Not as Bad for You as Smoking; Promotional Poster; CRUK: London, UK, 2017; Available online: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-us/cancer-news/press-release/2017-02-06-e-cigarettes-safer-than-smoking-says-long-term-study (accessed on 12 December 2017).

- Farrimond, H. E-cigarette regulation and policy: UK vapers’ perspectives. Addiction 2016, 111, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training. Training and Assessment Programme. Available online: http://www.ncsct.co.uk/publication_training-and-assessment-programme.php (accessed on 10 January 2018).

- Le Houezec, J.; Global Forum on Nicotine (GFN) Dialogue Speech. Presentation at the GFN Dialogues (Autumn 2017), Durham, UK, 2 November 2017; Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=17&v=k-W385qXc5I (accessed on 2 February 2018).

- National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training and New Nicotine Alliance. The Switch Films. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/user/NCSCTfilms/featured (accessed on 15 December 2017).

- Russell, C.; Dickson, T.; McKeganey, N. Advice from former-smoking e-cigarette users to current smokers on how to use e-cigarettes as part of an attempt to quit smoking. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2017, ntx176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirlway, F. Global Forum on Nicotine (GFN) Dialogue Speech. Presentation at the GFN Dialogues (Autumn 2017), Durham, UK, 2 November 2017; Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=3&v=LjHnkSFZpXY (accessed on 2 February 2017).

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ward, E.; Cox, S.; Dawkins, L.; Jakes, S.; Holland, R.; Notley, C. A Qualitative Exploration of the Role of Vape Shop Environments in Supporting Smoking Abstinence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020297

Ward E, Cox S, Dawkins L, Jakes S, Holland R, Notley C. A Qualitative Exploration of the Role of Vape Shop Environments in Supporting Smoking Abstinence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(2):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020297

Chicago/Turabian StyleWard, Emma, Sharon Cox, Lynne Dawkins, Sarah Jakes, Richard Holland, and Caitlin Notley. 2018. "A Qualitative Exploration of the Role of Vape Shop Environments in Supporting Smoking Abstinence" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 2: 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020297