Bread and Shoulders: Reversing the Downward Spiral, a Qualitative Analyses of the Effects of a Housing First-Type Program in France

Abstract

:1. Background

1.1. The Housing First Approach to Homelessness and Psychiatric Disorders

1.2. Recovery, Homelessness, and Psychiatric Disorders

1.3. The Recovery Paradigm in France

2. The French Un Chez Soi d’Abord Qualitative Study: Overview

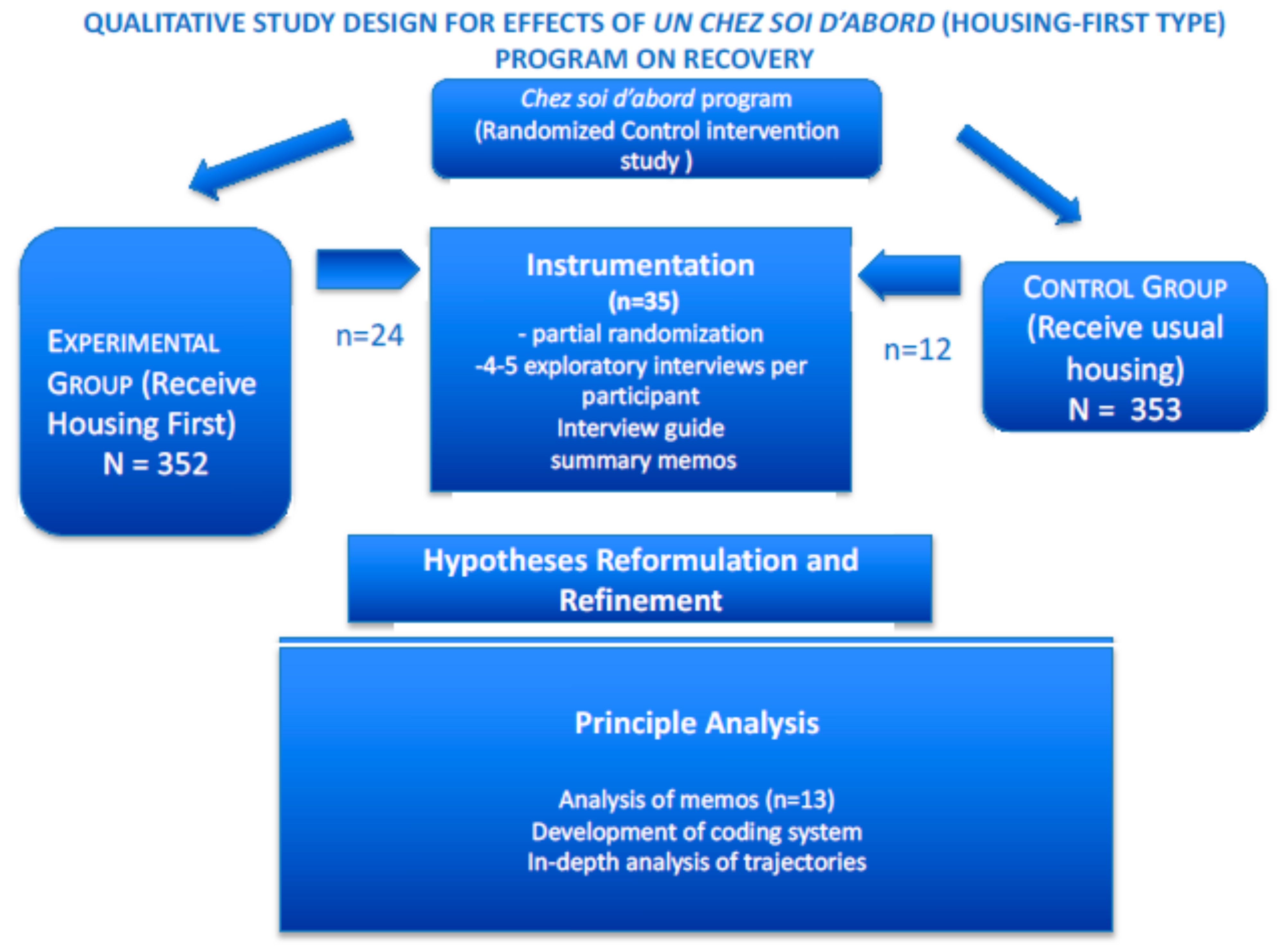

2.1. Presentation of the Study

2.2. Study Context:The Un Chez Soi d’Abord Randomized Controlled Trial Study

2.3. The Qualitative Study Component

2.4. Sampling Procedures

2.5. Analytic Strategy

3. Instrumentation Phase and Data Collection

3.1. Early Explorations and Instrument Development

3.2. Formalization of Interview Guidelines and Semi-Structured Interviews

4. Hypothesis Reformulation

5. Principal Analysis: Typology and Results

5.1. Analytic Strategy

5.2. Themes Emerging in Recovery Trajectories

5.2.1. A secure Space Favorable to Self-Reflexivity: “Settle down First, Start Thinking Later”

5.2.2. The Program’s “Honeymoon Effect”

“Before the program, no one helped me, I was hustling on my own.”

“It’s the first time I have had a choice. With this apartment… it’s the end of tough times.”

“Without Un Chez Soi d’Abord program, I never would have gotten an apartment.”

“I sleep better, eat better, I feel secure… The team brings me comfort.”

“Everything is better now. When I have a problem, I have someone I can count on.”

- T 0:

- My life is already better. I never thought that one day I’d have my own place. I had tears in my eyes when I got the envelope … I’m going to go to the self-help group, I’ll do everything I can to go… I hope I can hold myself together until my daughter has a child. I hope I’m not going to do what I used to do, wanting to end my life… Before, my life had no meaning.

- T + 3 months:

- No one loves me for who I am [he cries]. For years, I kept everything to myself, and now I’m just exploding and I turn away all the people who try to understand me.

- T + 12 months:

- I don’t like the Un Chez Ssoi d’Abord program’s group outings…First of all, I don’t want to see them. I hardly ever see [my partner]. Her place is tiny. She’s sick… It’s my weight that’s a problem. I lock myself in my house. I don’t even own clothes anymore… I went off my treatment cold turkey, it’s been six months, I know I got fat because of that… I don’t want to see a doctor… I no longer hear from my two children… Nothing is interesting to me except movies… I’m behind on my rent. I spent everything betting on the horses.

5.2.3. The Importance of Social Ties, Even When Weak

“My daughter… when I was homeless… I totally lost her. To find my father, I had to go to the cops, you know, like, start an investigation. And you know, he had really helped me when I was a kid. And then I’ve got memories—I can’t forget them. So I wanted to get in touch again. And then this weekend, he set up a meeting. He called me and he said, “I want to see you again”. So once in a while we’ll see each other. I took the train there yesterday. He was welcoming. Yeah, I was pleased.”

“It’s ancient history, I feel relaxed now. It’s been too long now. It’s been seven years. I know they know I was homeless. If they don’t know, that’s for the best. I would be ashamed because they’ve been working for several years; they have children, they have their house. Me, I didn’t do anything for 6 or 7 years. My mother, I know where she is. But it’s not good to talk to someone who’s bipolar, and the other way around, given her mental state.”

“My family? Oh, no, they’re miserable, always problems, fights, misunderstandings. It tires me out just talking about it. …my mother fell into alcoholism; my father is unhappy because his children didn’t do the right things like he wanted… My 22-year-old younger brother still rules at my mother’s house, and it’s difficult, so I’m in a hurry to leave… I’m leaving Friday and that’s already too long and I’m happy to leave. If not, there will be a murder. If I don’t leave, there will be a murder.”

5.2.4. Hope and Peer Support Give Meaning to Life

“We are not free in the shelter. At my age, freedom is important. I can live in a community if that community respects certain rules. It’s not easy. Sure, I need structure, but with structure there are always rules. If a person does not respect the rules, it creates bad vibes. The [shelter’s] schedule is one thing—waiting in the streets for three hours. I would go to M [another shelter], but you know, there’s a ton of people there and I don’t feel comfortable. It’s full of lost souls. How can I pull through if I hang out with them? Right now, I don’t have the energy. I need to socialize with people who aren’t losers.”

“Honestly, that’s the shitty mistake I made. If I had to talk to people who did not feel comfortable with themselves. Asking for help is not a weakness, maybe it’s even a strength. When we ask for help and we receive it, it means that on the one hand, there’s someone there for us, and that’s a strength not a weakness… it’s better to have someone around. What happened to me, is that when I started freaking out, being paranoid… I tried to fight it alone. I wouldn’t dare to… I had a feeling—how can I put it—of embarrassment. And I would tell myself that I’ve been in top shape for the past two years: I have an apartment, I’m self-confident, I was able to finish my studies and then all of the sudden I start going downhill, just like that. I didn’t want people to know. But the best thing to do is still to talk about it. The team [assigned to me], they are important. As much as they ever were, except it’s my turn to ask for their help. They are still as important, but if I don’t go see them, they won’t come to me. They aren’t in my head”.

5.3. The Complexity of Recovery Trajectories

5.3.1. A Balance between Risk and Protection

“Boxes of Risperdal are all I have in my fridge. Because I was in prison, my disability check was cut by 30%. So, I only get 250 euro (instead of almost 800). I have to give social services the paper that says I was released from prison, and they’ll get me back my disability check. My guardian had to pay the landlord and the electricity bill. So, I have nothing to eat and nothing to smoke. I keep trying to apply for benefits, but as I’m on disability benefits already and I’m under guardianship, I get nothing.”

5.3.2. Combining Factors in Recovery: Dilemmas and Vicious Circles

“Actually, it’s been ages since we’ve seen each other (…) and I don’t have enough money to take the two trains to go visit them… Last month, my daughter asked me to give her some pocket money for the annual sales. I wasn’t able to. I stopped paying child support because I was sick of it. I did something else with that money—I bought some boots and a pair of jeans. I get no news from my daughters. They never call me… As for the child support people, they’re going to summon me soon. That bothers me a lot. I have to ask for an evaluation all over again. I feel all over the place about that. It’s pretty intense. I feel guilty for not paying child support for the past two months. I’m afraid to call my daughters because their mother might answer. I’m waiting to get a job so that I can start paying child support again (…) I could call my old lawyer (…) but I don’t have the energy. In the present situation, I’m running away from things instead of facing them. It’s my fault because I spent all my money on cocaine. If I admit that, it will be used against me. Even today, with a home, I can’t make it mentally. It’s crazy.”

5.3.3. A Typology of Trajectories

Shifts in Trajectories Produced by Program Effects

- 1.-Sabine

- Cushioning Effect

- Type 1 Trajectory

- 2-Fouad

- Intermittent Positive Effects

- Type 2 Trajectory

- 3-Christian

- Rebound Effect

- Type 3 Trajectory

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Availability of Data and Material

Funding

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsemberis, S.; Gulcur, L.; Nakae, M. Housing First, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, P.H.; Wright, J.D.; Fisher, G.A.; Willis, G. The urban homeless: Estimating composition and size. Science 1987, 235, 1336–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmer, T.P.; Stefancic, A.; Ettner, S.L.; Manning, W.G.; Tsemberis, S. Effect of full-service partnerships on homelessness, use and costs of mental health services, and quality of life among adults with serious mental illness. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latimer, E.A.; Rabouin, D.; Cao, Z.; Ly, A.; Powell, G.; Aubry, T.; Distasio, J.; Hwang, S.W.; Somers, J.M.; Stergiopoulos, V.; et al. Costs of Services for Homeless People with Mental Illness in 5 Canadian Cities: A Large Prospective Follow-up Study. CMAJ Open 2017, 5, E576–E585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, C.; Rich, A.R. Outcomes of homeless adults with mental illness in a housing program and in case management only. Psychiatr. Serv. 2003, 354, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefancic, A.; Tsemberis, S. Housing First for long-term shelter dwellers with psychiatric disabilities in a suburban county: A four-year study of housing access and retention. J. Prim. Prev. 2007, 28, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.P.; Rollins, A.L. The Meaning of Recovery from Co-Occurring Disorder: Views from Consumers and Staff Members Living and Working in Housing First Programming. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2015, 13, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kirst, M.; Zerger, S.; Harris, D.W.; Plenert, E.; Stergiopoulos, V. The promise of recovery: Narratives of hope among homeless individuals with mental illness participating in a Housing First randomised controlled trial in Toronto, Canada. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittman, F.D.; Polcin, D.L.; Sheridan, D. The Architecture of Recovery: Two Kinds of Housing Assistance for Chronic Homeless Persons with Substance Use Disorders. Drugs Alcohol. Today 2017, 17, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, M.L.; Currie, L.; Rezansoff, S.; Somers, J.M. Exiting homelessness: Perceived changes, barriers, and facilitators among formerly homeless adults with mental disorders. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2015, 38, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauly, B.; Gray, E.; Perkin, K.; Chow, C.; Vallance, K.; Krysowaty, B.; Stockwell, T. Finding safety: A pilot study of managed alcohol program participants’ perceptions of housing and quality of life. Harm Reduct. J. 2016, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henwood, B.F.; Cabassa, L.J.; Craig, C.M.; Padgett, D.K. Permanent supportive housing: Addressing homelessness and health disparities? Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103 (Suppl. S2), S188–S192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polvere, L.; Macnaughton, E.; Piat, M. Participant perspectives on housing first and recovery: Early findings from the At Home/Chez Soi project. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2013, 36, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornes, M.; Manthorpe, J.; Joly, L.; O’Halloran, S. Reconciling recovery, personalisation and Housing First: Integrating practice and outcome in the field of multiple exclusion homelessness. Health Soc. Care Community 2014, 22, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, L.; Rakfeldt, J.; Strauss, J.; Davidson, L.; Rakfeldt, J.; Strauss, J. The Roots of Recovery Movement in Psychiatry: Lessons Learned; Willey-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; 282p. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus, H.A.; Spaeth-Rublee, B.; Sara, G.; Goldner, E.M.; Prince, P.N.; Ramanuj, P.; Gaebel, W.; Zielasek, J.; Großimlinghaus, I.; Wrigley, M.; et al. A Review of Mental Health Recovery Programs in Selected Industrialized Countries. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2016, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padgett, D.; Henwood, B.F.; Tsemberis, S.J. Housing First: Ending Homelessness, Transforming Systems, and Changing Lives; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, W. Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc. Rehabil. J. 1993, 16, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, N.; Greenley, D. What Is Recovery? A Conceptual Model and Explication. Psychiatr. Serv. 2001, 52, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amering, M.; Schmolke, M. Recovery in Mental Health: Reshaping Scientific and Clinical Responsibilities; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, K. Rethinking social recovery in schizophrenia: What a capabilities approach might offer. Soc. Sci. Med. 1982, 65, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, L.; Borg, M.; Marin, I.; Topor, A.; Mezzina, R.; Sells, D. Processes of Recovery in Serious Mental Illness: Findings from a Multinational Study. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil. 2005, 8, 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric, M.; Townley, G.; Nelson, G.; Caplan, R.; Macleod, T.; Polvere, L.; Isaak, C.; Kirst, M.; McAll, C.; Nolin, D.; et al. How does Housing First catalyze recovery? Qualitative findings from a Canadian multi-site randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil. 2016, 19, 136–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goering, P.; Girard, V.; Aubry, T.; Barker, J.; Fortanier, C.; Latimer, E.; Laval, C.; Tinland, C. Conducting Policy Relevant Trials of a Housing First Intervention: A Tale of two countries. Liens Social et Politiques 2012, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Girard, V.; Driffin, K.; Musso, S.; Naudin, J.; Rowe, M.; Davidson, L.; Lovell, A.M. La relation thérapeutique sans le savoir Approche anthropologique de la rencontre entre travailleurs pairs et personnes sans chez-soi ayant une cooccurrence psychiatrique. L’évolution Psychiatrique 2006, 71, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cardinal, P. Le ‘pair-aidant’, l’espoir du rétablissement, Prévenir la rechute. Santé Mentale 2008, 133, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Deegan, P.E. Recovery: The lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosoc. Rehabil. J. 1988, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachoud, B.; Leplège, A.; Plagnol, A. La problématique de l’insertion professionnelle des personnes présentant un handicap psychique: Les différentes dimensions à prendre en compte. Revue Française des Affaires Sociales 2009, 1, 257–277. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, A.M.; Troisoeufs, A.; Mora, M. Du handicap psychique aux paradoxes de sa reconnaissance: Éléments d’un savoir ordinaire des personnes vivant avec un trouble psychique grave. Revue Française des Affaires Sociales 2009, 1, 209–227. [Google Scholar]

- Greacen, T.; Jouet, E. Pour des Usagers de la Psychiatrie Acteurs de Leur Propre Vie. Available online: https://www.cairn.info/pour-des-usagers-de-la-psychiatrie-acteurs-de-leur--9782749216089.htm (accessed on 14 March 2018).

- Moreau, D.; Laval, C. Care et recovery: Jusqu’où ne pas décider pour autrui? L’exemple du programme «Un chez-soi d’abord». Eur. J. Disabil. Res. 2015, 9, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinland, A.; Fortanier, C.; Girard, V.; Laval, C.; Videau, B.; Rhenter, P.; Greacen, T.; Falissard, B.; Apostolidis, T.; Lançon, C.; et al. Evaluation of the Housing First program in patients with severe mental disorders in France: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2013, 14, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Glaser, B. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, U.C.; Kharawala, S. Informed consent in psychiatry clinical research: A conceptual review of issues, challenges, and recommendations. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2012, 3, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeste, D.V.; Saks, E. Decisional capacity in mental illness and substance use disorders: Empirical database and policy implications. Behav. Sci. Law 2006, 24, 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, G.; Sarradon-Eck, A.; Payan, N.; Bonin, J.; Perrot, S.; Vialars, V.; Boyer, L.; Tinland, A.; Simeoni, M. The analysis of a mobile mental health outreach team activity: From psychiatric emergencies on the street to practice of hospitalization at home for homeless people. Presse Medicale 2012, 41, E226–E237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A.; Strauss, A.L. Basics of Qualitative Research; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, L. Living Outside Mental Illness: Qualitative Studies of Recovery in Schizophrenia; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, A.M.; Pandolfo, S.; Das, V.; Laugier, S. Face aux Désastres: Une Conversation à Quatre Voix sur le” Care”, la Folie et les Grandes Détresses Collectives; Ithaque: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grard, J. Frontières Invisibles: L’expérience de Personnes Prises en Charge au Long Cours par la Psychiatrie Publique en France; EHESS: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Capability and Well-Being. In The Quality of Life; Nussbaum, M., Sen, A., Eds.; Oxford Clarendon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 30–53. [Google Scholar]

- Martucelli, D. Forgé par L’épreuve. L’individu Dans la France Contemporaine; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Castel, R.; Martin, C. Changements et Pensées du Changement; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J. Democr. 1995, 6, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamson, W.A. Talking Politics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Noiseux, S. Élaboration D’une Théorie du Rétablissement de Personnes Vivant Avec la Schizophrénie. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett, D.K.; Henwood, B.; Abrams, C.; Drake, R.E. Social relationships among persons who have experienced serious mental illness, substance abuse, and homelessness: Implications for recovery. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2008, 78, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henwood, B.F.; Matejkowski, J.; Stefancic, A.; Lukens, J.M. Quality of life after housing first for adults with serious mental illness who have experienced chronic homelessness. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 220, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Initial Interviews—1–2 per Participant |

|---|

| Challenges, constraints and favorable aspects of participant’s life conditions |

| Relationship to the body, health, health behavior and coping |

| Aspirations and projections for the future |

| Relationship to home |

| Past and present relationships to services |

| Social relations (friends, family, urban acquaintances) |

| Places for sociocultural, leisure and pleasure |

| “Ontological sense”: security/insecurity |

| Social utility: social usefulness/uselessness |

| Well-being/malaise |

| Relationship (absent/present) to surrounding world |

| Beliefs, spiritual references, and relations to the religious. |

| Subsequent Interviews—2–4 per Participant |

|---|

| Trajectories of vulnerability |

| Helping relations and obstructive relations |

| Effectiveness of choices |

| Challenges to reconfiguration of identity |

| Challenges to experiential learning |

| Challenges to the appropriation of ability to act |

| Challenges to citizenship practices. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rhenter, P.; Moreau, D.; Laval, C.; Mantovani, J.; Albisson, A.; Suderie, G.; French Housing First Study Group; Boucekine, M.; Tinland, A.; Loubière, S.; et al. Bread and Shoulders: Reversing the Downward Spiral, a Qualitative Analyses of the Effects of a Housing First-Type Program in France. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030520

Rhenter P, Moreau D, Laval C, Mantovani J, Albisson A, Suderie G, French Housing First Study Group, Boucekine M, Tinland A, Loubière S, et al. Bread and Shoulders: Reversing the Downward Spiral, a Qualitative Analyses of the Effects of a Housing First-Type Program in France. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(3):520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030520

Chicago/Turabian StyleRhenter, Pauline, Delphine Moreau, Christian Laval, Jean Mantovani, Amandine Albisson, Guillaume Suderie, French Housing First Study Group, Mohamed Boucekine, Aurelie Tinland, Sandrine Loubière, and et al. 2018. "Bread and Shoulders: Reversing the Downward Spiral, a Qualitative Analyses of the Effects of a Housing First-Type Program in France" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 3: 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030520