A Dynamic Control Strategy for Hybrid Electric Vehicles Based on Parameter Optimization for Multiple Driving Cycles and Driving Pattern Recognition

Abstract

:1. Introduction

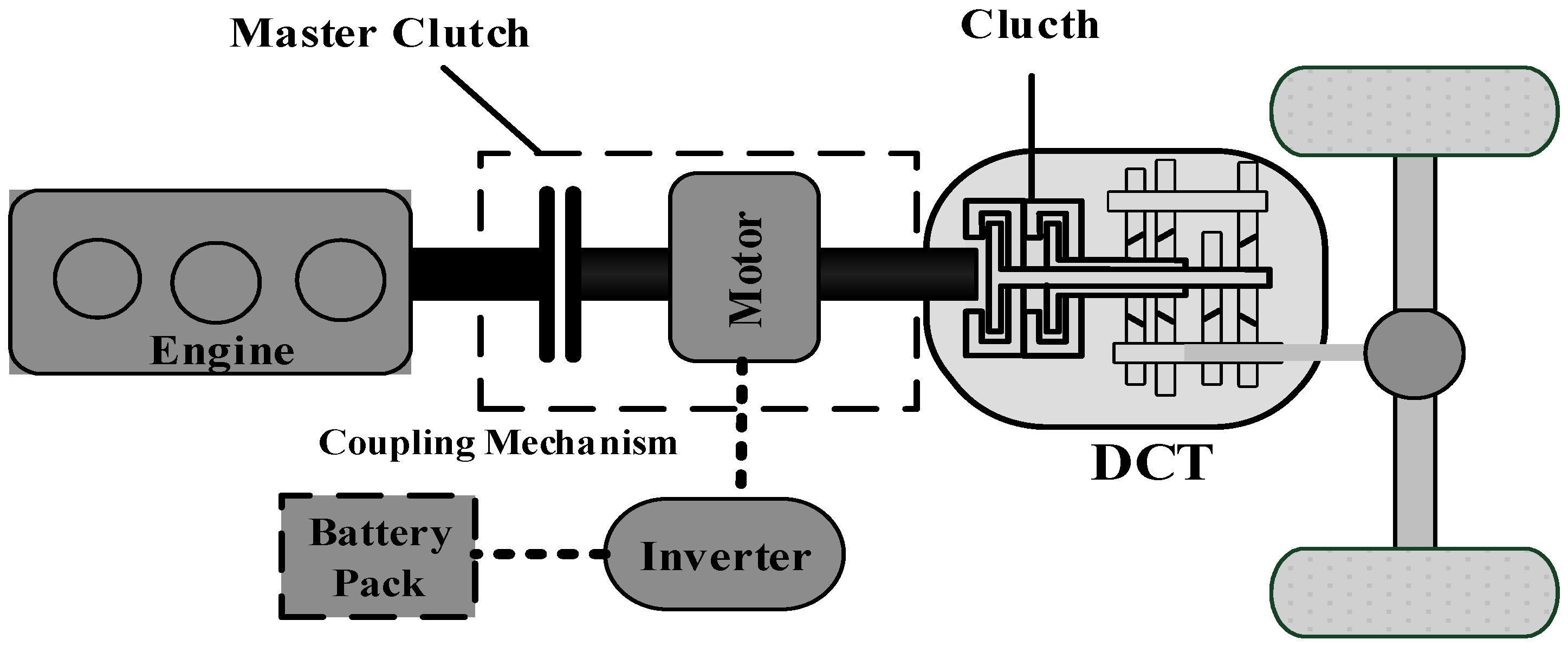

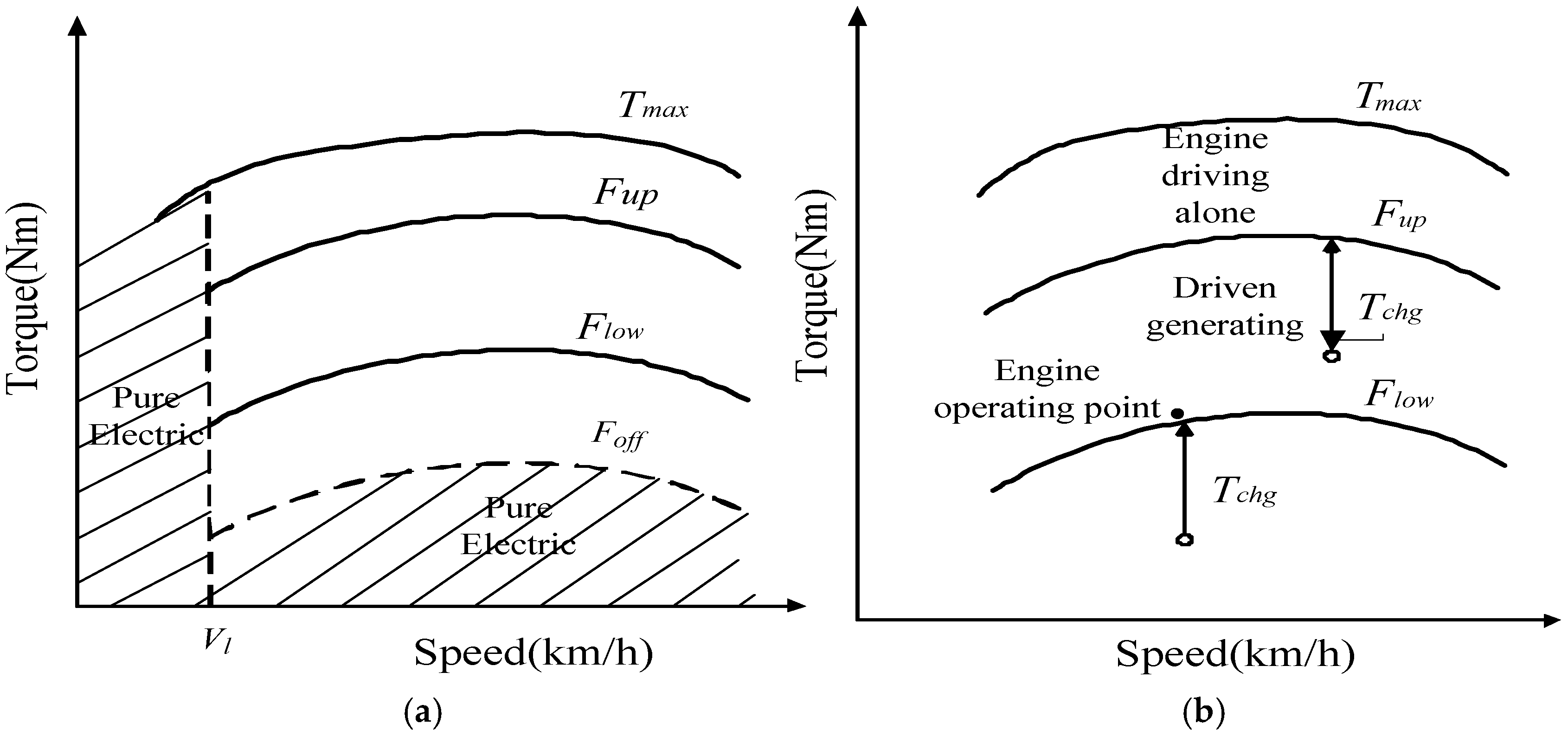

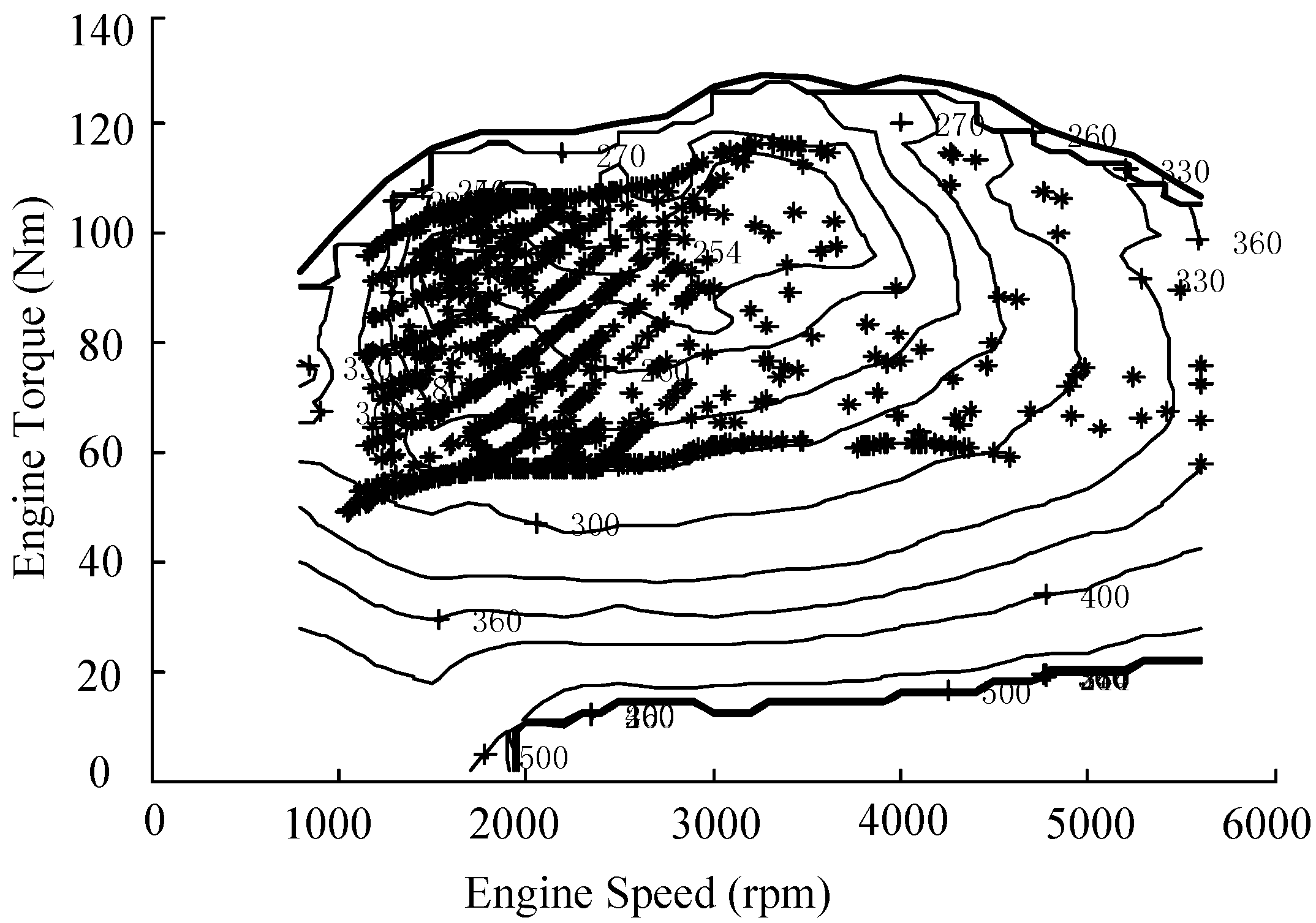

2. Hybrid Electric Vehicle (HEV) Rule-Based Energy Management Control Strategy

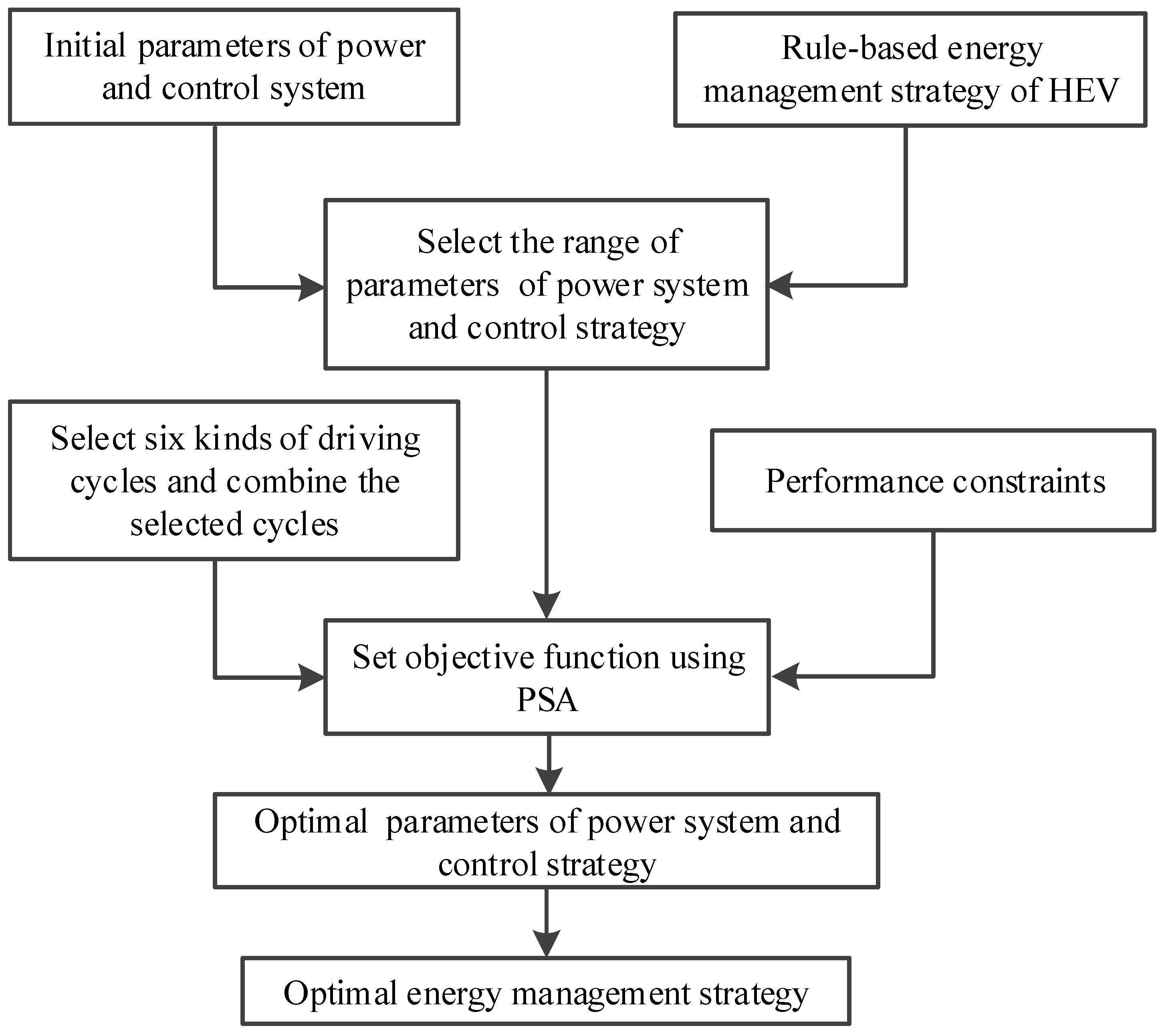

3. Power System and Control Strategy Parameter Optimization Based on Multiple Driving Cycles

3.1. Basic Idea for Parameter Optimization

- (1)

- The assumption that the revised rule-based EMS is used for HEV.

- (2)

- The initial parameters of power system and control strategy are selected and their values are chosen.

- (3)

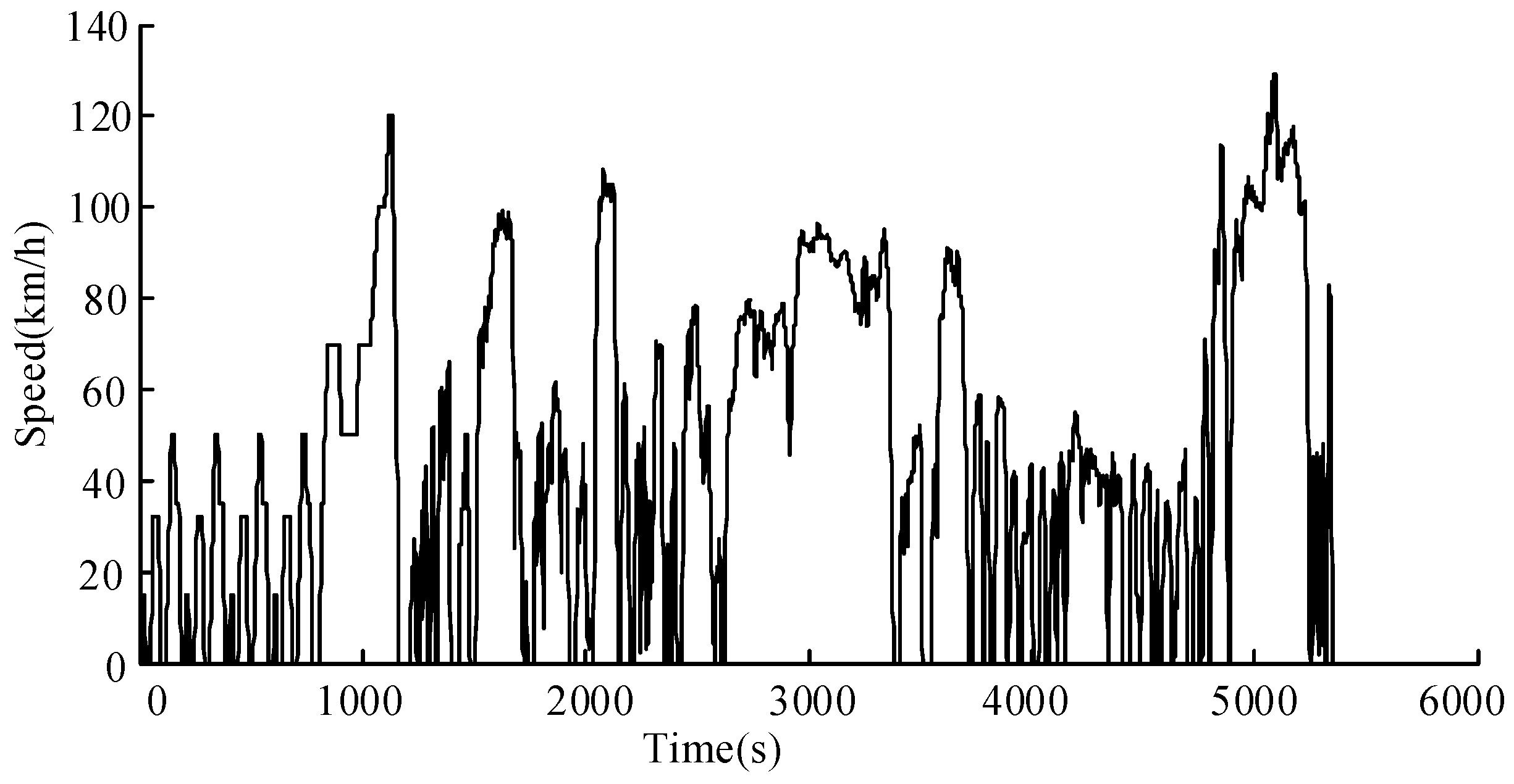

- Six types of driving cycles are selected and combined into a comprehensive driving cycle.

- (4)

- The simultaneous optimization for the main parameters of power system and control strategy is carried out using SA-PSO algorithm with vehicle performance constraints.

- (5)

- The optimal power system and control parameters are applied to the HEV EMS.

3.2. Parameter Definition of Power System and Control Strategy

3.3. State of Charge-Fuel Consumption Correction Method

3.4. Optimization Objective Function

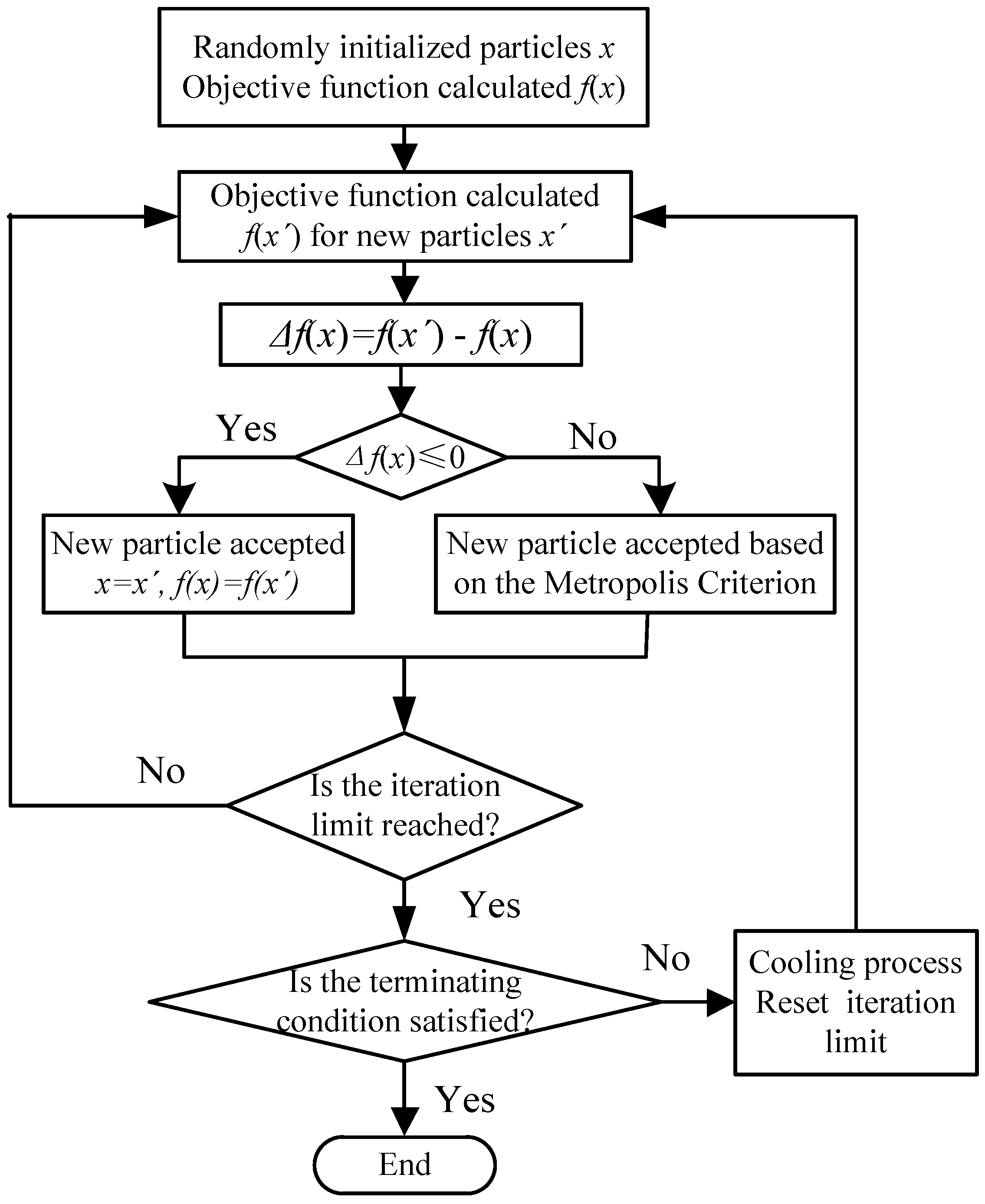

3.5. Parameter Optimization for HEV Based on Simulated Annealing Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm

- Step 1: Initialize a group of random particles. The inertia should be chosen to provide a balance between the global and local exploration. The initialization consists of the following major parameters:

- Generation number: 25 Constants; c1 and c2: 2.05, 2.05; Initial temperature T: 9000 °C; Final temperature T0: 0.05 °C; Anneal speed K: 0.9.

- Step 2: Calculate and update the fitness function f(x) of all particles. Determine and of the current generation. Update new velocities and positions of each particle according to Equations (3) and (4).

- Step 3: Calculate the difference between the optimal and non-optimal function value Δf(x). Accept the optimal solution if Δf(x) is greater than 0, otherwise generate a random number r within (0, 1). When r is lower than , accept the optimal solution and go to Step 2, or go to the next step.

- Step 4: Introduce the simulated annealing mechanism. Stop the program and output the optimal solution if the convergence criteria is satisfied, otherwise carry out the annealing process and the command “T = 0.9 × T”.

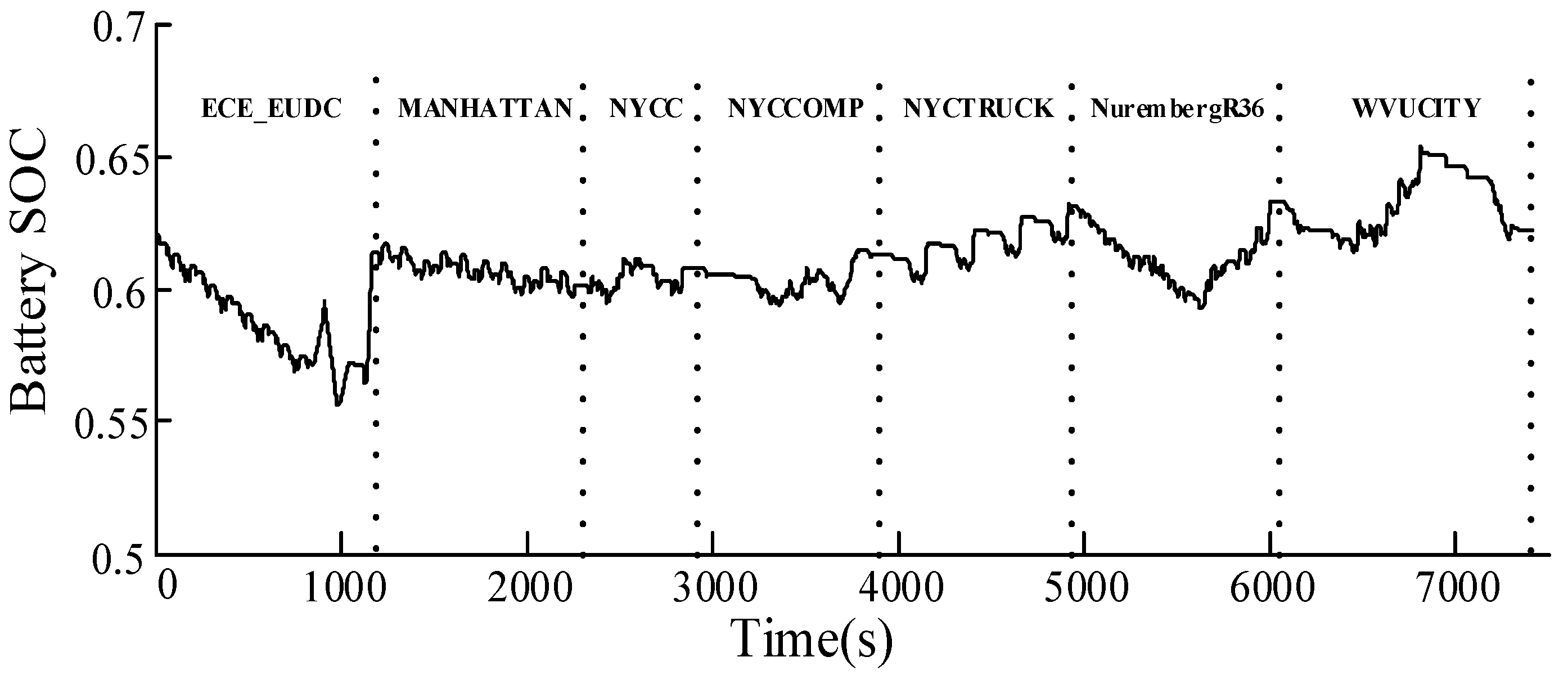

3.6. Simulation of Optimal Parameters Based on Multiple Driving Cycles

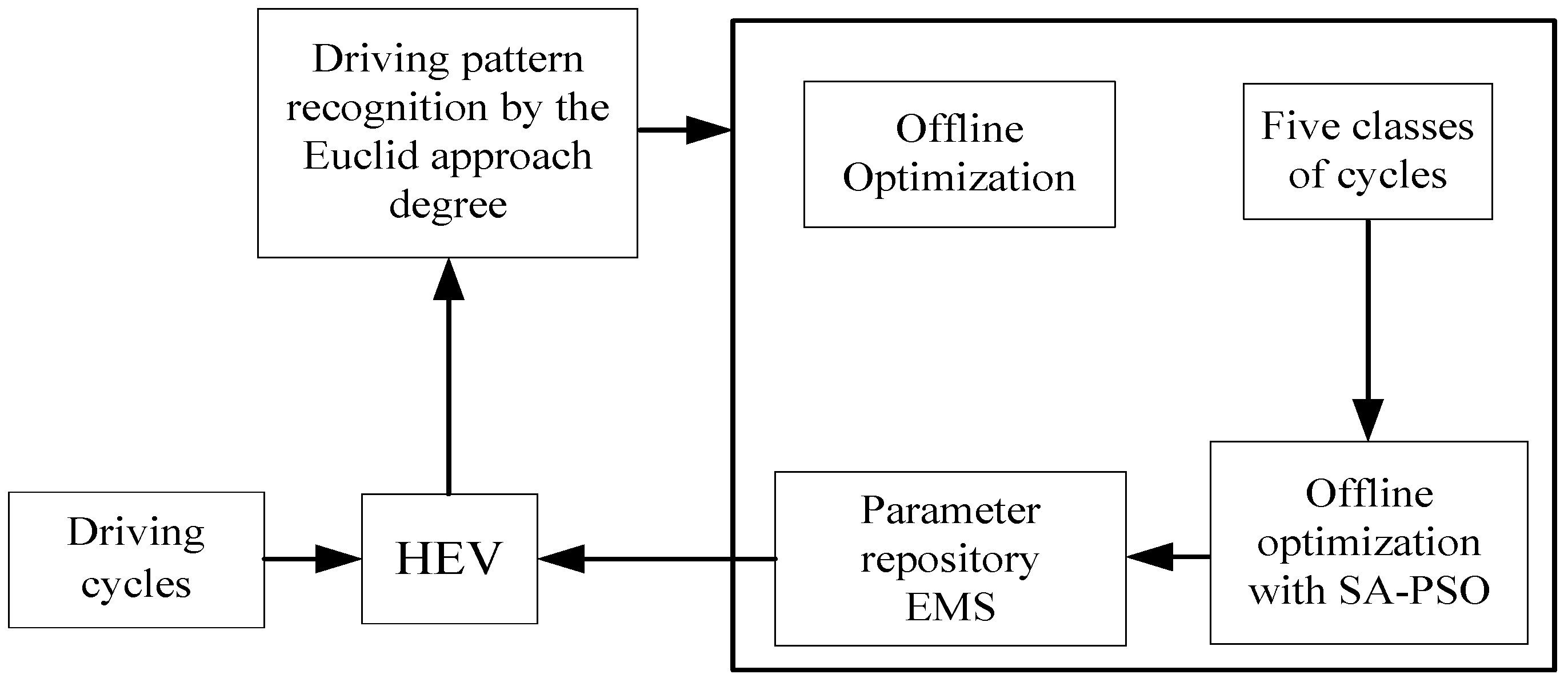

4. HEV Dynamic Control Strategy Based on Driving Pattern Recognition

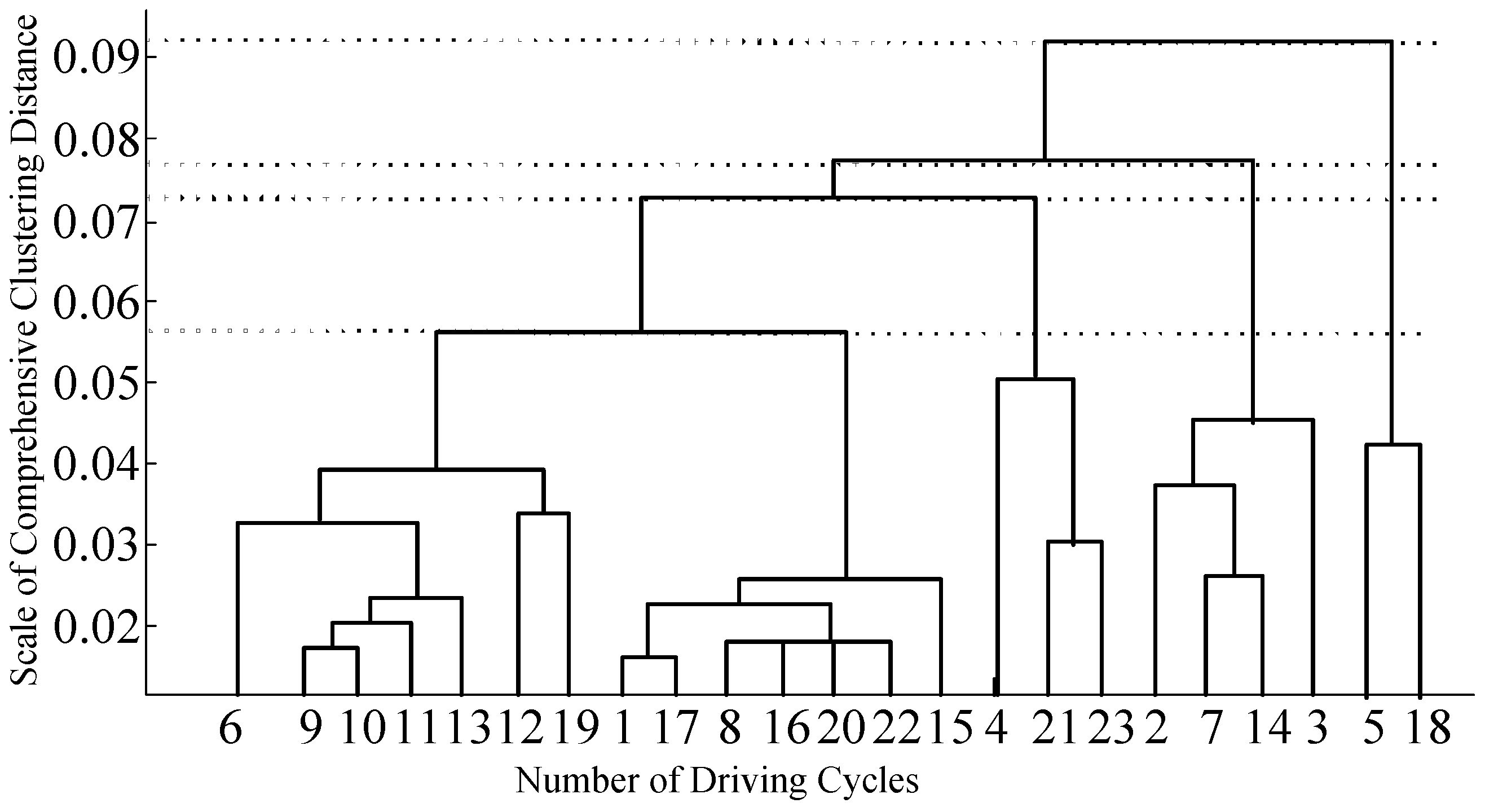

4.1. Selection and Classification of Characteristic Parameters for Typical Patterns

4.2. Recognition and Parameter Optimization of Driving Patterns

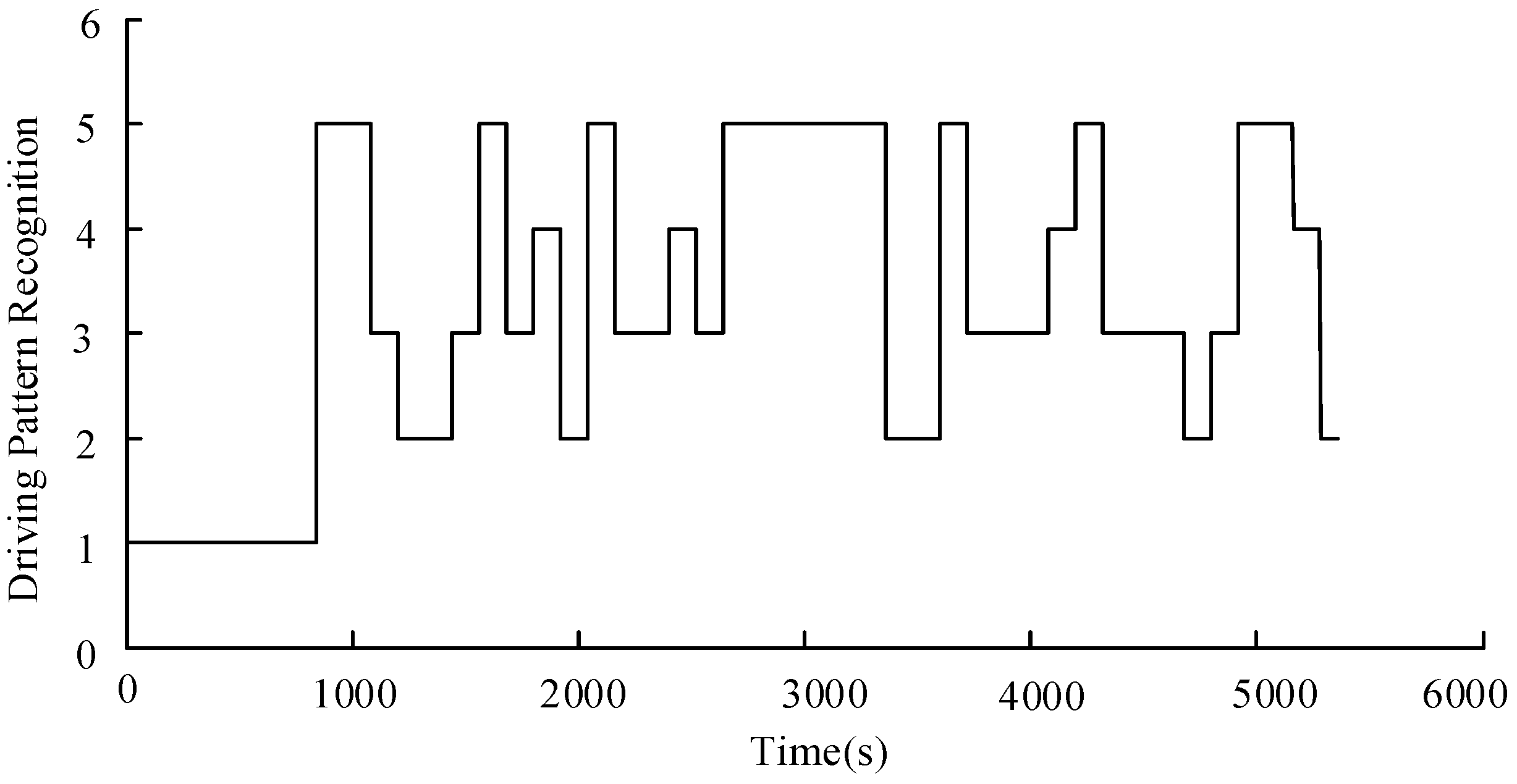

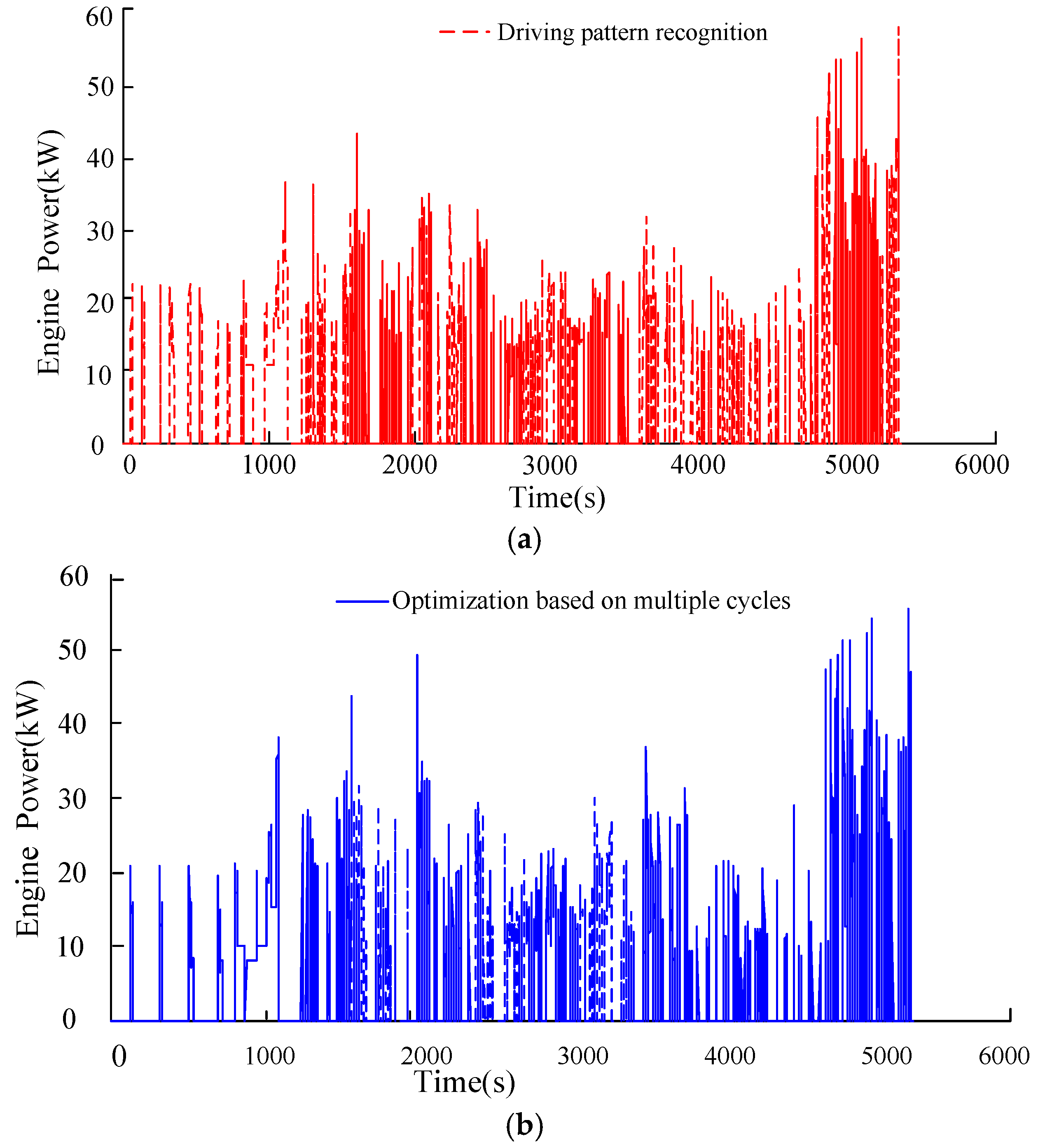

4.3. Optimization of Control Parameters Based on Driving Pattern Recognition

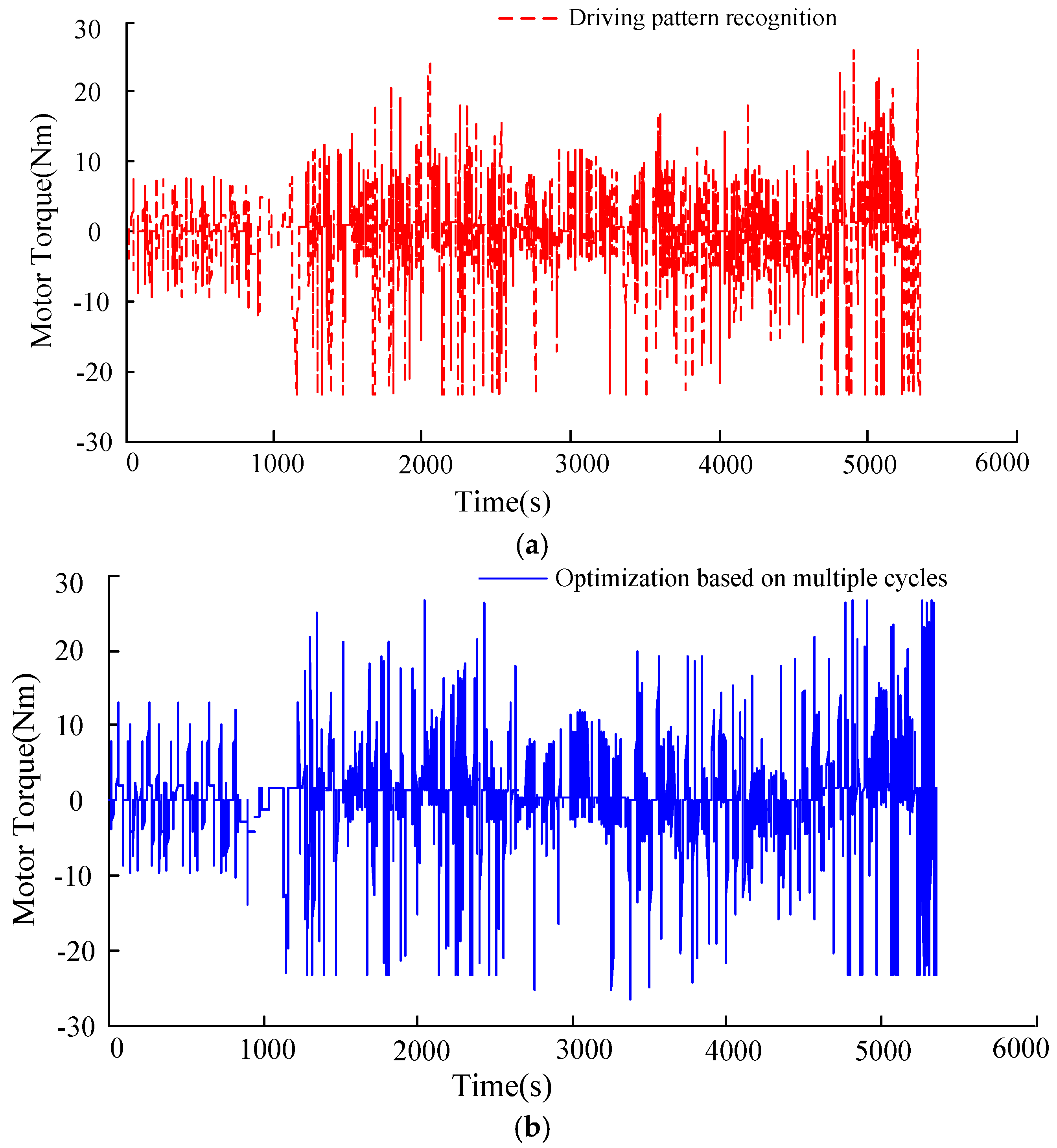

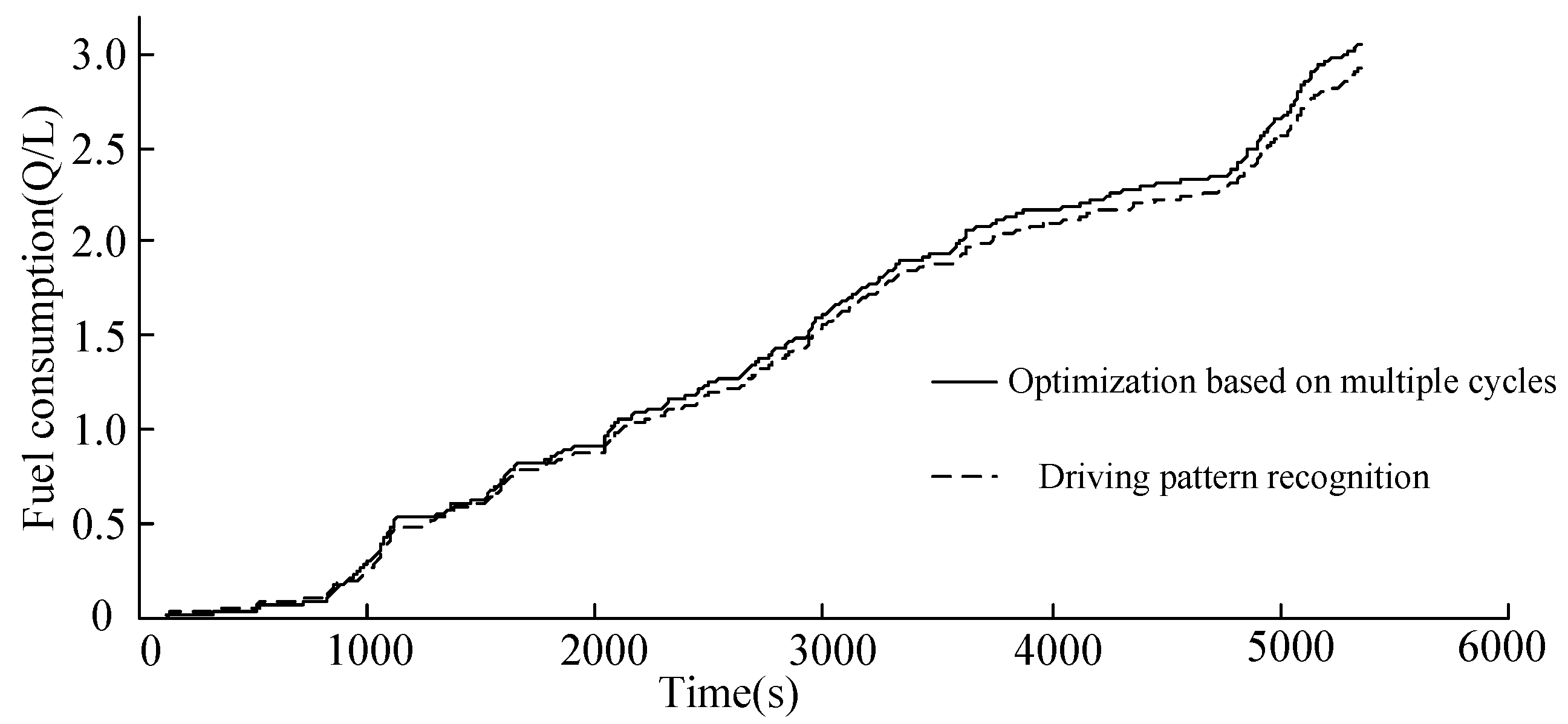

5. Simulation

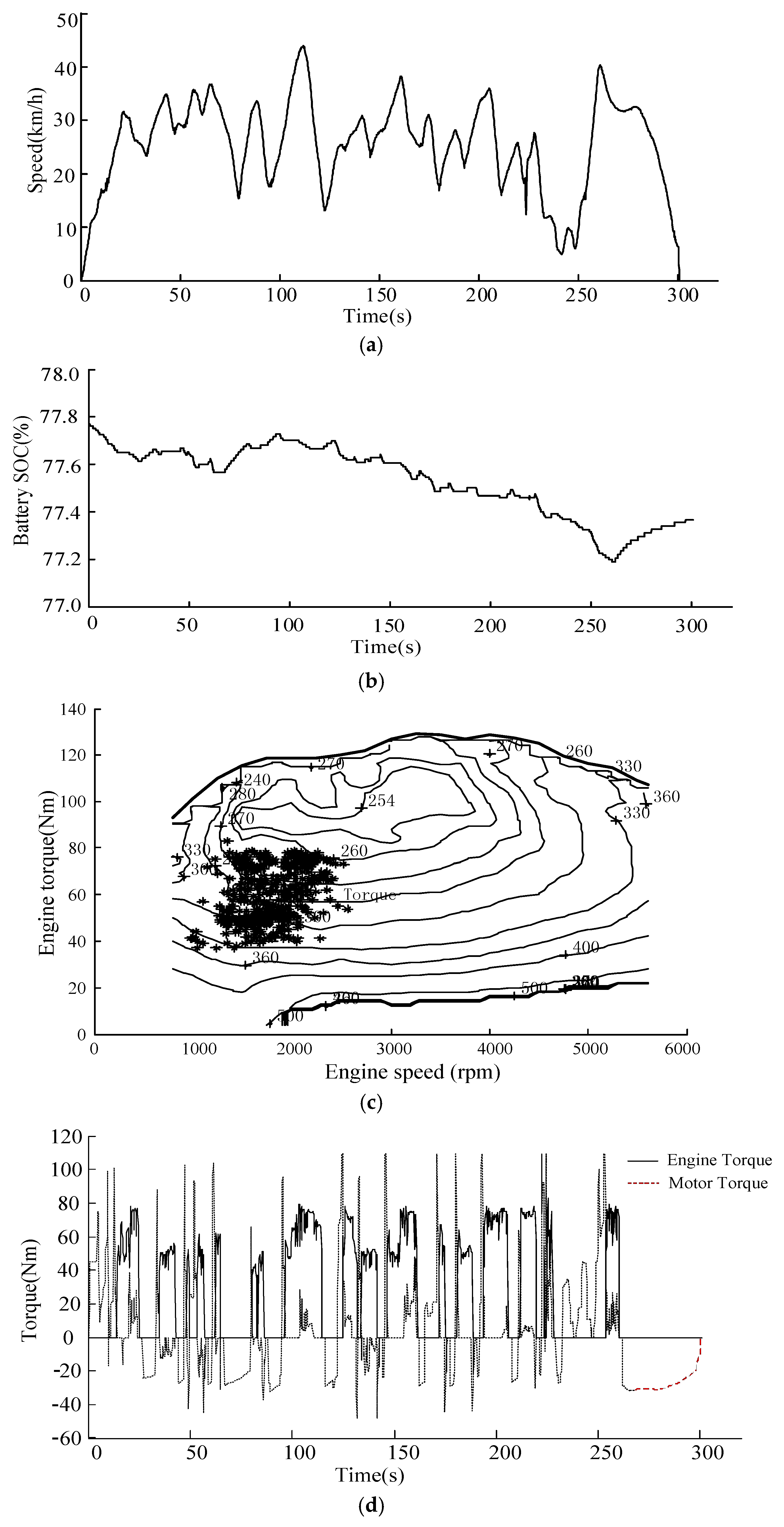

6. Road Test on the Prototype Vehicle

- (1)

- Since the prototype HEV can only be tested on campus, for the sake of safety, the road test is only carried out at the low speed. Although the campus condition is only classified as an urban driving cycle, it is still valid to analyze the effectiveness of the proposed optimization method of HEV control strategy.

- (2)

- The required torque during the whole test is too small compared with the maximum capacity of the HEV power system. To ensure that the vehicle operates in each mode without loss of generality, the parameters Foff = 0.20, Flow = 0.44, Fup = 0.64, Vl = 15 are designed as the optimal control strategy parameters according to the actual test conditions.

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- A new methodology for parameter optimization under multiple driving cycles using SA-PSO algorithm is proposed to the simultaneous optimization for parameters of power system and control strategy. It’s beneficial to achieve the best fuel consumption without impairing the dynamic performance.

- (2)

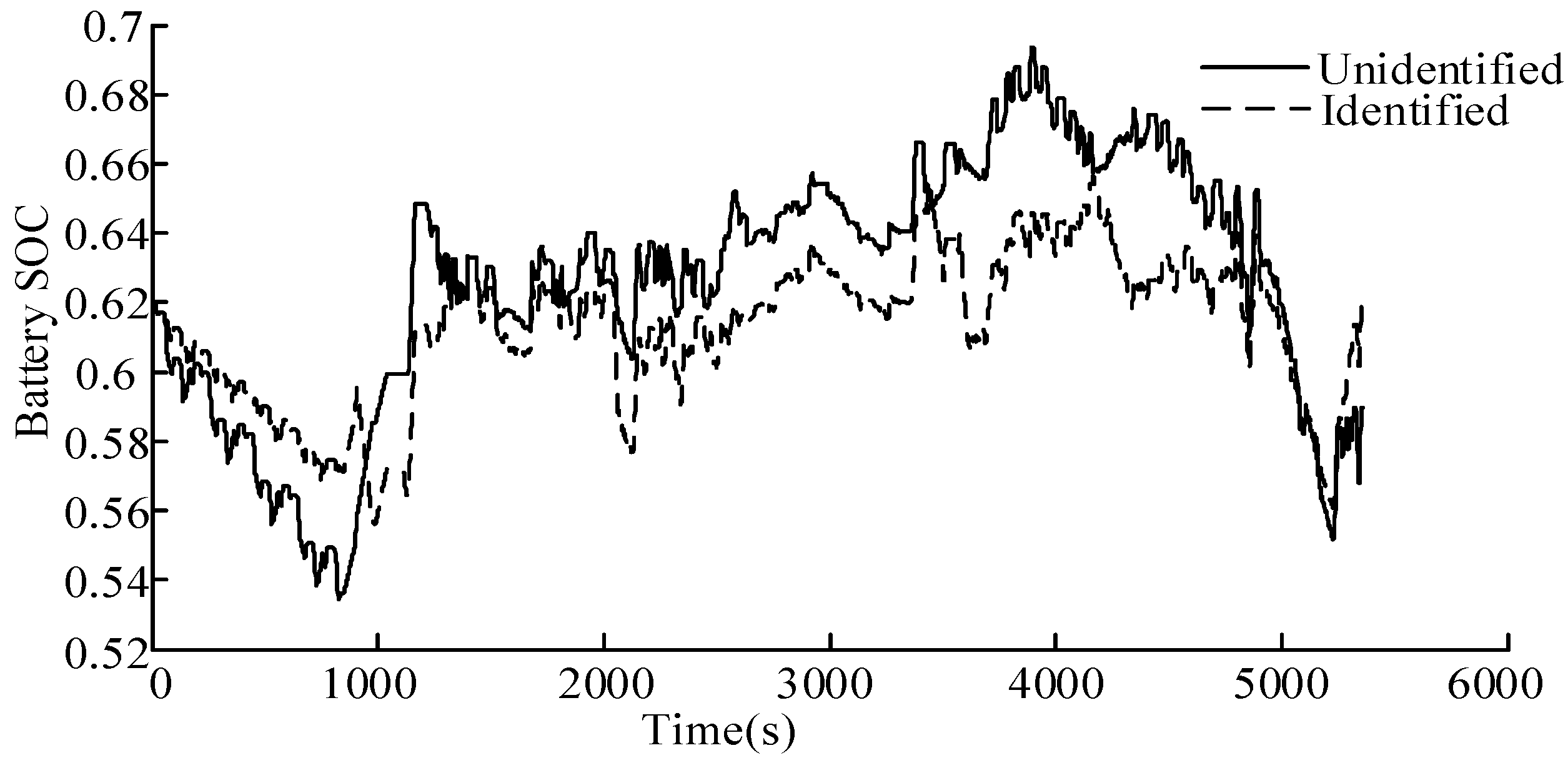

- The EMS of HEVs based on driving pattern recognition, which optimizes the control parameters in real-time, is proposed after the parameter optimization under multiple driving cycle conditions. The proposed dynamic control strategy for HEVs based on parameter optimization under multiple driving cycles and driving pattern recognition has been simulated using Matlab/Simulink platform under the comprehensive driving cycle. Basically, the problem that the optimization based on a certain driving cycle cannot keep the battery SOC balance in other cycles has been solved in this paper.

- (3)

- The simulation results show that compared with the original EMS, the former strategy reduces the fuel consumption by 4.36% and the latter one reduces the fuel consumption by 11.68%. The results validate the fact that the fuel consumption of EMS based on driving pattern recognition is greatly improved compared with that of the rule-based control strategy and more effective than that of multiple driving cycles. Meanwhile, the variation of battery SOC with the EMS based on driving pattern recognition is more reasonable than that of the optimization based on multiple driving cycles. It will serve as a guideline for calibrating the key parameters for road test.

- (4)

- The proposed dynamic control strategy for HEVs based on driving pattern recognition is validated on a prototype HEV by a road test. The test results show that the EMS developed in this paper can effectively distribute the engine torque and motor torque, and significantly improve the fuel consumption of the vehicle. Furthermore, the battery SOC fluctuates smoothly and the battery SOC balance is well maintained during the test process. It will serve a reference role in dynamic control strategy for HEVs in real world.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fang, L.; Qin, S.; Xu, G.; Li, T.; Zhu, K. Simultaneous optimization for hybrid electric vehicle parameters based on multi-objective genetic algorithms. Energies 2011, 4, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri-Gh, M.A. Application of genetic algorithm for optimization of control strategy in parallel hybrid electric vehicles. J. Frankl. Inst. 2006, 343, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panday, A.; Bansal, H.O. Energy Management strategy for hybrid electric vehicles using genetic algorithm. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2016, 8, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, P.; Han, B. The optimization of control parameters for hybrid electric vehicles based on genetic algorithm. In Proceedings of the SAE World Congress, Detroit, MI, USA, 8–10 April 2014.

- Varesi, K.; Radan, A. A Novel GA Based Technique for Optimizing Both the Design and Control Parameters in Parallel Passenger Hybrid Cars. Int. Rev. Electr. Eng. 2011, 63, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zeng, X.; Zhou, N.; Li, L. The Algorithmic Research of Multi-Operating Mode Energy Management System; SAE Technical Paper 2013-01-0988; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.A.; Wang, X.M.; He, H.W.; Guo, H.Q.; Tang, H.L. Powertrain matching based on driving cycle for fuel cell hybrid electricvehicle. Mech. Mater. 2013, 288, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, C.H.; Cui, N.X. PSO Algorithn-based parameter optimization for HEV powertrain and its control strategy. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2008, 38, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Xiong, R.; He, H. A systematic state-of-charge estimation framework for multi-cell battery pack in electric vehicles using bias correction technique. Appl. Energy 2016, 162, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xiong, R.; Wang, K.; Jiao, B. Optimal energy management strategy of a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle based on a particle swarm optimization algorithm. Energies 2015, 8, 3661–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Qin, S. Concurrent optimization for parameters of powertrain and control system of hybrid electric vehicle based on multi-objective genetic algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2006 SICE-ICASE International Joint Conference, Busan, Korea, 18–21 October 2006.

- Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, C.; Jiao, X.; Zhang, L.; Song, J. Hybrid genetic algorithm-based optimization of powertrain and control parameters of plug-in hybrid electric bus. J. Frankl. Inst. 2015, 352, 776–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Shen, P.; Zhan, X. optimization of key parameters of energy management strategy for hybrid electric vehicle using DIRECT algorithm. Energies 2016, 9, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.W.; Chen, K.L. Simulated Annealing Particle Swarm Algorithm Based Parameters Optimization for Hybrid Electric Vehicles. Autom. Eng. 2012, 34, 580–584. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, H.K.; McGordon, A.; Jennings, P.A. A generalized powertrain design optimization methodology to reduce fuel economy variability in hybrid electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2014, 63, 1055–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Xiong, R. Adaptive energy management of a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle based on driving pattern recognition and dynamic programming. Appl. Energy 2015, 155, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xiong, R.; Cao, J. Particle swarm optimization-based optimal power management of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles considering uncertain driving conditions. Energy 2016, 96, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.I.; Jo, S.; Park, Y.; Lee, J. Multi-mode driving control of a parallel hybrid electric vehicle using driving pattern recognition. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control Trans. ASME 2002, 124, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Jeon, S.; Peng, H. Driving pattern recognition for control of hybrid electric trucks. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2004, 42, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X. Intelligent energy management based on driving cycle identification using fuzzy neural network. In Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Design, Changsha, China, 12–14 December 2009; pp. 501–504.

- Dayeni, M.K.; Soleymani, M. Intelligent energy management of a fuel cell vehicle based on traffic condition recognition. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2016, 18, 1945–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Q.N.; Zeng, X.H.; Wang, P.Y.; Wang, J.N. Driving cycle recognition neural network algorithm based on the sliding time window for hybrid electric vehicles. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2015, 16, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Chen, Z.; Kiliaris, L.; Kuang, M.L.; Masrur, M.A.; Phillips, A.M.; Murphey, Y.L. Intelligent vehicle power control based on machine learning of optimal control parameters and prediction of road type and traffic congestion. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2009, 58, 4741–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Tan, Y.; He, X. An Intelligent Multifeature Statistical Approach for the Discrimination of Driving Conditions of a Hybrid Electric Vehicle. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2010, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xiong, R.; Cao, J.Y. Battery durability and longevity based power management for plug-in hybrid electric vehicle with hybrid energy storage system. Appl. Energy 2016, 179, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, E.; Ruiz, J.; Astruc, D. Power Management Optimization of an Experimental Fuel Cell/Battery/Supercapacitor Hybrid System. Energies 2015, 8, 6302–6327. [Google Scholar]

- Meintz, A.; Ferdowsi, M. Control strategy optimization for a parallel hybrid electric vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference (VPPC ‘08), Harbin, China, 3–5 September 2008.

- Wu, L.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, X.; Chen, Z. Multiobjective optimization of HEV fuel economy and emissions using the self-adaptive differential evolution algorithm. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2011, 60, 2458–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metropolis, N.; Rosenbluth, A.W.; Rosenbluth, M.N.; Teller, M.; Teller, E. Equation of state calculations by very fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 1953, 21, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, H.L.; Kuo, C.C.; Chiang, C.M. Modified particle swarm optimization algorithm with simulated annealing behavior and its numerical verification. Appl. Math. Comput. 2011, 218, 4365–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, V.H.; Wipke, K.B.; Rausen, D.J. HEV Control Strategy for Real Time Optimization on Fuel Economy and Emission. In Proceedings of the 2000 Future Car Congress, Arlington, VA, USA, 2–6 April 2000.

- Pisu, P.; Rizzoni, G. A comparative study of supervisory control strategies for hybrid electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2007, 15, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.; Xie, W.; Gautam, M.; Lyons, D.W.; Norton, P.; Balon, T. Hybrid Diesel-Electric Heavy Duty Bus Emissions: Benefits of Regeneration and Need for State of Charge Correction. In Proceedings of the 2000 International Fall Fuels and Lubricants Meeting and Exposition, Baltimore, MD, USA, 16–19 October 2000.

| Operating Mode | Constraint Condition | Torque Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Electric Driving Mode | 0 < Tv ≤ Toff SOCup > SOC > SOClow; V > Vl SOCup > SOC > SOClow; V ≤ Vl SOC > SOCup | Tm = Tv; Te = 0 |

| Driving & Charging Mode | Toff < Tv ≤ Tlow SOClow ≤ SOC ≤ SOCup; V > Vl 0 ≤ Tv ≤ Tup | Te = Tlow Tm = Tv − Tlow Te = Tup Tm = max(Tv − Tup, Tchg max) |

| Engine Driving Mode | Tlow ≤ Tv ≤ Tup SOCup > SOC > SOClow; V > Vl Tup ≤ Tv; SOC ≤ SOClow | Te = Tv; Tm = 0 |

| Motor Driving Mode | Tup < Tv; SOC > SOClow; V > Vl | Te = Tup; Tm = Tv − Tup |

| Regenerative Braking Mode | Tv ≤ 0; SOC < SOCup | Tv = Tm + Tmechanic |

| Tv ≤ 0 and SOC > SOCup | Tv = Tmechanic |

| Name | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|

| SOCup | - | Maximum expectation of battery SOC |

| SOClow | - | Minimum expectation of battery SOC |

| V | km/h | Current speed |

| Vl | km/h | Speed floor. When SOC > SOClow and V < Vl, pure electric mode starts |

| Tmax | Nm | Maximum steady-state torque of engine |

| Foff | - | Engine off torque coefficient, |

| Flow | - | Minimum torque coefficient of engine in high efficiency regions, |

| Fup | - | Maximum torque coefficient of engine in high efficiency regions, |

| Tchg | Nm | Active charging torque of ISG motor. Tchg max is the maximum charging torque of motor |

| Tv | Nm | Vehicle demand torque |

| Tm | Nm | Output torque of the ISG |

| Te | Nm | Output torque of the engine |

| Tmechanic | Nm | Mechanic braking torque |

| Max. Speed | Max. Slope of Climb | Acceleration Time from 0 to 100 km/h | |

|---|---|---|---|

| km/h | % | s | |

| 160 | ≥50 | ≥30 | ≤12 |

| (Engine Driving Mode) | (Electric Driving Mode) | (Engine Driving Mode) | (Hybrid Driving Mode) |

| Mode | FTP | LA92 | SC03 | UDDS | HWFET | US06_HWY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | urban congestion | suburban | highway | |||

| Description | Engine (PIC) | ISG Motor (PISG) |

|---|---|---|

| Max Power (kW) | 72 | 30 |

| Max Torque (Nm) | 137 | 115 |

| Optimal Variable | Initial Value | Variation Range |

|---|---|---|

| PIC (kW) | 72.0 | 21.6–122.4 |

| PISG (kW) | 30.0 | 9–51 |

| Flow | 0.6 | 0.43–0.73 |

| Fup | 0.9 | 0.75–0.93 |

| Foff | 0.235 | 0.2–0.4 |

| SOClow | 0.25 | 0.2–0.4 |

| SOCup | 0.8 | 0.75–0.9 |

| Vl | 32 | 10–50 |

| Optimal Variable | Initial Value | Optimal Value |

|---|---|---|

| PIC (kW) | 72.0 | 67.0 |

| PISG (kW) | 30.0 | 26.0 |

| Flow | 0.6 | 0.48 |

| Fup | 0.9 | 0.90 |

| Foff | 0.235 | 0.23 |

| SOClow | 0.25 | 0.30 |

| SOCup | 0.8 | 0.78 |

| Vl | 32 | 35.06 |

| Mode | vmax | vavg | amax | dmax | aavg | davg | ri |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 69.97 | 22.68 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.32 |

| 2 | 64.37 | 39.70 | 1.07 | 2.01 | 0.60 | 1.79 | 0.22 |

| 3 | 32.19 | 20.42 | 0.98 | 2.06 | 0.81 | 1.79 | 0.214 |

| 4 | 32.19 | 14.85 | 0.36 | 0.62 | 0.29 | 0.56 | 0.187 |

| 5 | 88.51 | 70.28 | 1.03 | 2.01 | 0.28 | 1.89 | 0.122 |

| 6 | 119.99 | 32.11 | 1.05 | 1.39 | 0.54 | 0.79 | 0.277 |

| 7 | 128.75 | 85.75 | 3.58 | 2.55 | 1.29 | 0.80 | 0.097 |

| 8 | 108.15 | 39.61 | 3.08 | 3.93 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.163 |

| 9 | 40.72 | 10.98 | 2.06 | 2.50 | 0.54 | 0.67 | 0.362 |

| 10 | 44.58 | 11.41 | 2.68 | 2.64 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.351 |

| 11 | 57.94 | 14.10 | 4.11 | 3.88 | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0.331 |

| 12 | 54.72 | 12.15 | 1.96 | 1.87 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.52 |

| 13 | 53.70 | 14.34 | 1.88 | 2.11 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.31 |

| 14 | 129.23 | 82.88 | 3.79 | 3.19 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.034 |

| 15 | 88.19 | 34.50 | 2.28 | 2.73 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.195 |

| 16 | 91.25 | 31.51 | 1.48 | 1.48 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 0.189 |

| 17 | 93.34 | 30.32 | 1.96 | 2.07 | 0.48 | 0.58 | 0.333 |

| 18 | 129.23 | 97.91 | 3.08 | 3.08 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.033 |

| 19 | 57.65 | 13.58 | 1.14 | 3.24 | 0.30 | 0.39 | 0.303 |

| 20 | 72.10 | 25.86 | 1.30 | 2.16 | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.252 |

| 21 | 129.20 | 70.03 | 3.53 | 3.62 | 0.66 | 0.70 | 0.075 |

| 22 | 49.99 | 18.26 | 1.06 | 0.83 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.33 |

| 23 | 91.23 | 47.07 | 1.47 | 1.56 | 0.44 | 0.68 | 0.05 |

| Classes | Flow | Fhigh | Foff | Vl |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 0.50 | 0.80 | 0.25 | 23.66 |

| Second | 0.48 | 0.90 | 0.23 | 35.06 |

| Third | 0.63 | 0.83 | 0.32 | 11.77 |

| Forth | 0.59 | 0.917 | 0.33 | 23.64 |

| Fifth | 0.68 | 0.80 | 0.40 | 15.98 |

| Mode | ECE_EUDC | MAN-HATTAN | NYCC | NYC-COMP |

| ΔSOC | −0.007 | −0.017 | 0.01 | 0.009 |

| Mode | NYC-TRUCK | NuremberR36 | WVU-CITY | Comprehensive |

| ΔSOC | 0.02 | 0.006 | −0.015 | 0.005 |

| Factor | Rule-Based Control Strategy | Multiple Driving Cycles Optimization | Driving Pattern Recognition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel Consumption (L) | 3.23 | 3.10 | 2.96 |

| Corrected Fuel Consumption (L) | 3.43 | 3.28 | 3.03 |

| Q100 (L/100 km) | 4.75 | 4.55 | 4.36 |

| Corrected Q100 (L/100 km) | 5.05 | 4.83 | 4.46 |

| Fuel Saving | - | 4.24% | 8.24% |

| Fuel Saving (SOC corrected) | - | 4.36% | 11.68% |

| ΔSOC | −0.28 | −0.250 | −0.098 |

| Main Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Curb weight (kg) | 1350 |

| Rated payload (kg) | 1875 |

| Effective radius (m) | 0.295 |

| Frontal area (m2) | 2.28 |

| Maximum engine torque (Nm) | 137 |

| Nominal motor power (kW) | 20 |

| Rated voltage (V) | 288 |

| Factor | Rule-Based Control Strategy | Multiple Driving Cycles Optimization | Driving Pattern Recognition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Mileage (km) | 21.67 | 22.23 | 21.24 |

| Fuel Consumption (L) | 1.38 | 1.34 | 1.25 |

| Corrected Fuel Consumption (L) | 1.45 | 1.40 | 1.27 |

| Corrected Q100 (L/100 km) | 6.69 | 6.30 | 5.98 |

© 2017 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lei, Z.; Cheng, D.; Liu, Y.; Qin, D.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Q. A Dynamic Control Strategy for Hybrid Electric Vehicles Based on Parameter Optimization for Multiple Driving Cycles and Driving Pattern Recognition. Energies 2017, 10, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/en10010054

Lei Z, Cheng D, Liu Y, Qin D, Zhang Y, Xie Q. A Dynamic Control Strategy for Hybrid Electric Vehicles Based on Parameter Optimization for Multiple Driving Cycles and Driving Pattern Recognition. Energies. 2017; 10(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/en10010054

Chicago/Turabian StyleLei, Zhenzhen, Dong Cheng, Yonggang Liu, Datong Qin, Yi Zhang, and Qingbo Xie. 2017. "A Dynamic Control Strategy for Hybrid Electric Vehicles Based on Parameter Optimization for Multiple Driving Cycles and Driving Pattern Recognition" Energies 10, no. 1: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/en10010054