Study on Flow in Fractured Porous Media Using Pore-Fracture Network Modeling

Abstract

:1. Introduction

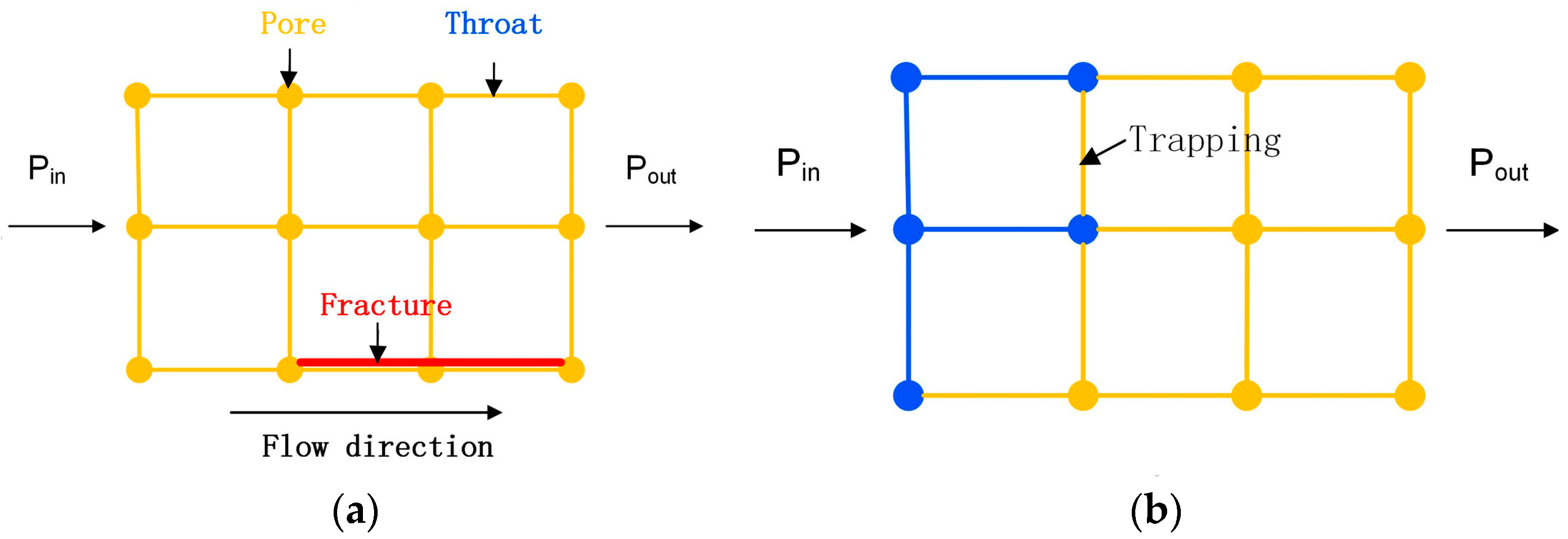

2. Pore-Fracture Network Model

2.1. Brief Introduction of Model

2.2. Governing Equations

2.2.1. Equations for Flow in Throats and Fractures

2.2.2. Calculation of Macro-Parameters

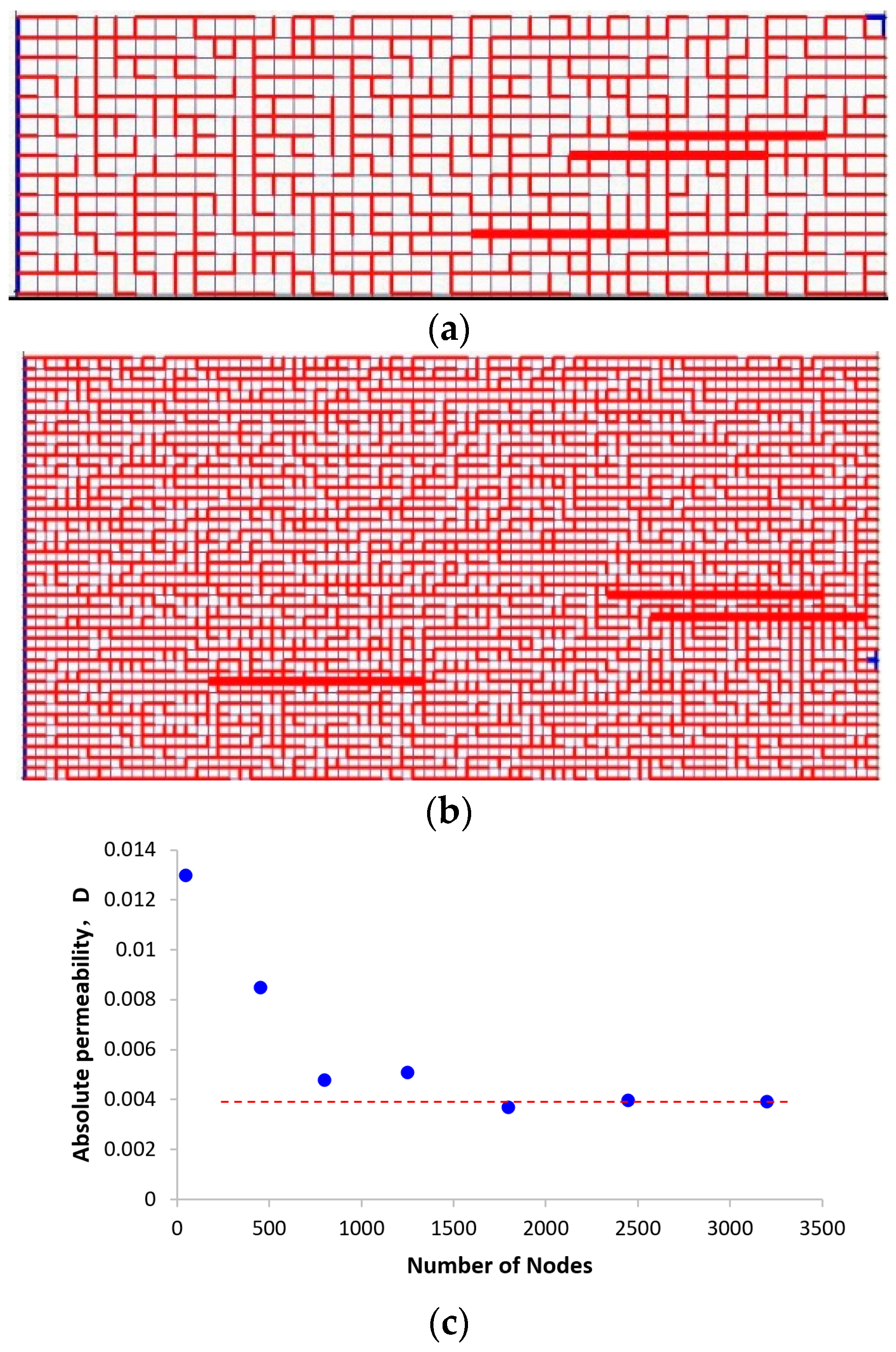

2.3. Computational Procedures

- Generation of PFNM: the statistical properties and topological parameters of the actual porous media are obtained first according to the measured data, including the size and direction distribution of the throats and fractures, coordination number, and spatial correlation. Then, PFNM is generated by the method introduced in Section 2.1.

- Computation of the absolute permeability: Let the wetting phase (water) flow through the network to obtain the absolute permeability using Equation (9).

- Computation of the irreducible water saturation: Let the non-wetting phase (oil) displace the wetting phase (water) based on the end status of Step ii. The water that has not been displaced forms the irreducible water.

- Computation of the residual oil saturation: Water flooding is processed to displace the oil in the network based on the end status of Step iii. Once the oil cannot flow out the network, the displacement is finished. Then, the residue oil, relative permeability, and oil displacement efficiency are calculated.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Two Flow Patterns in the Network

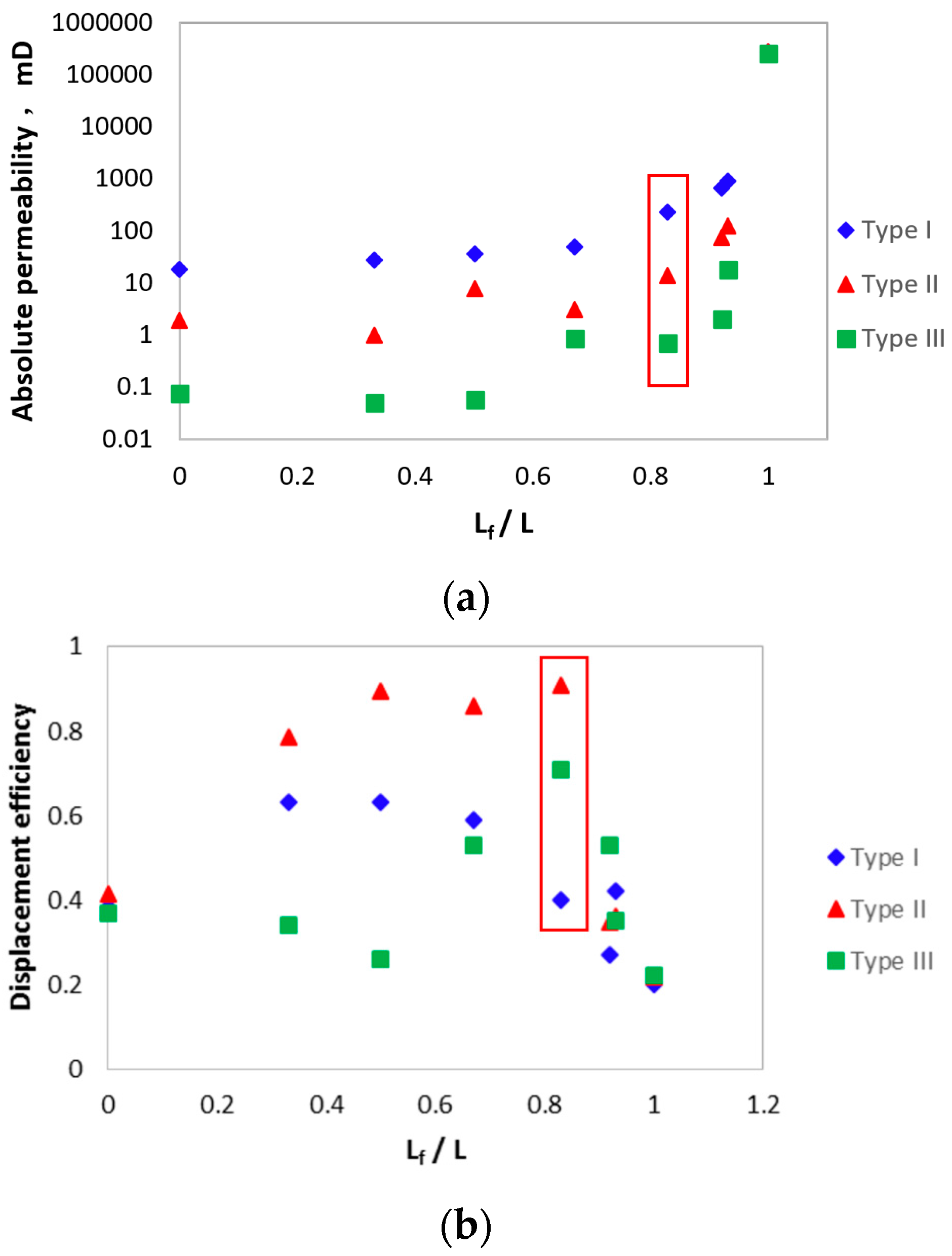

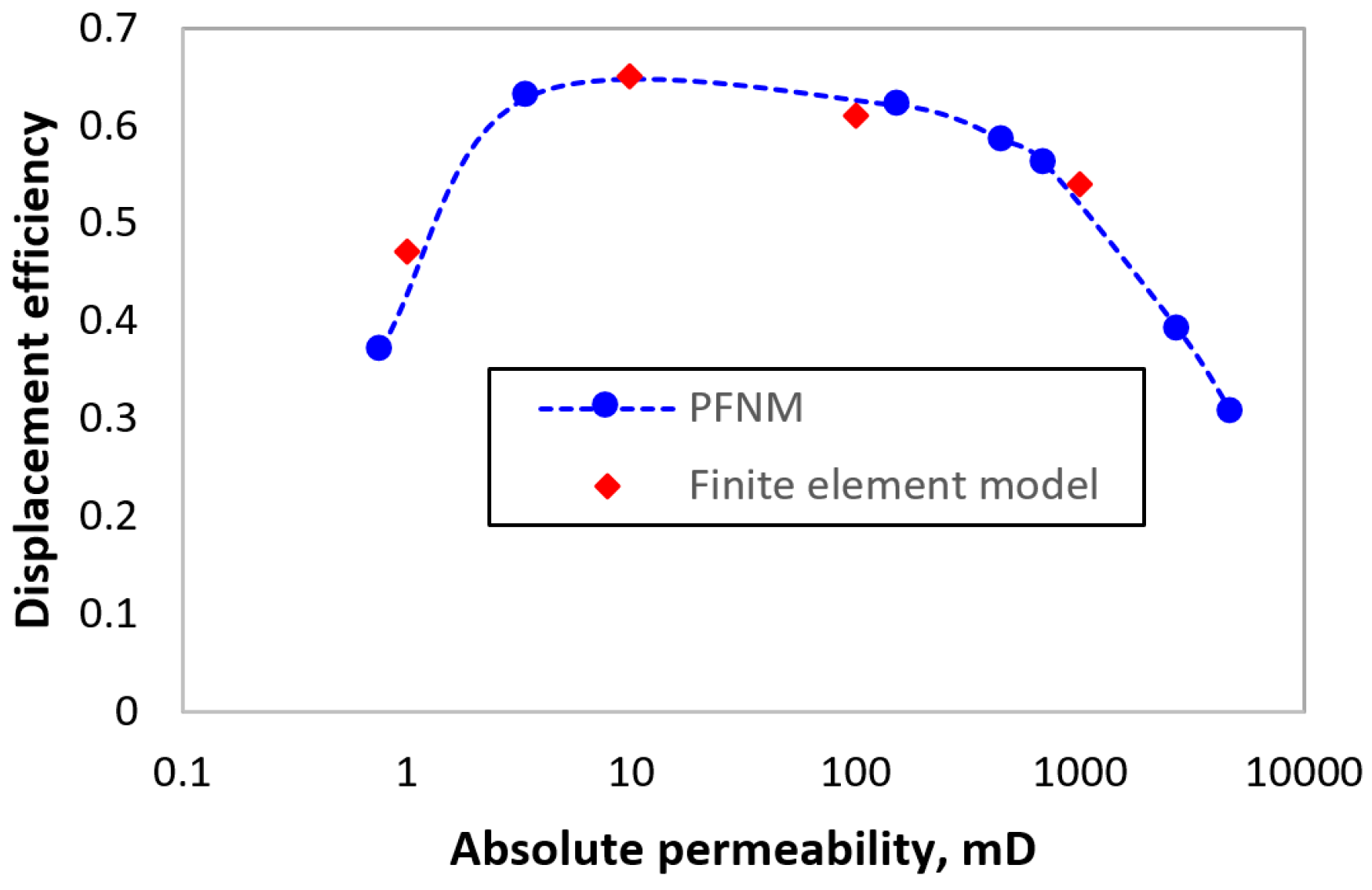

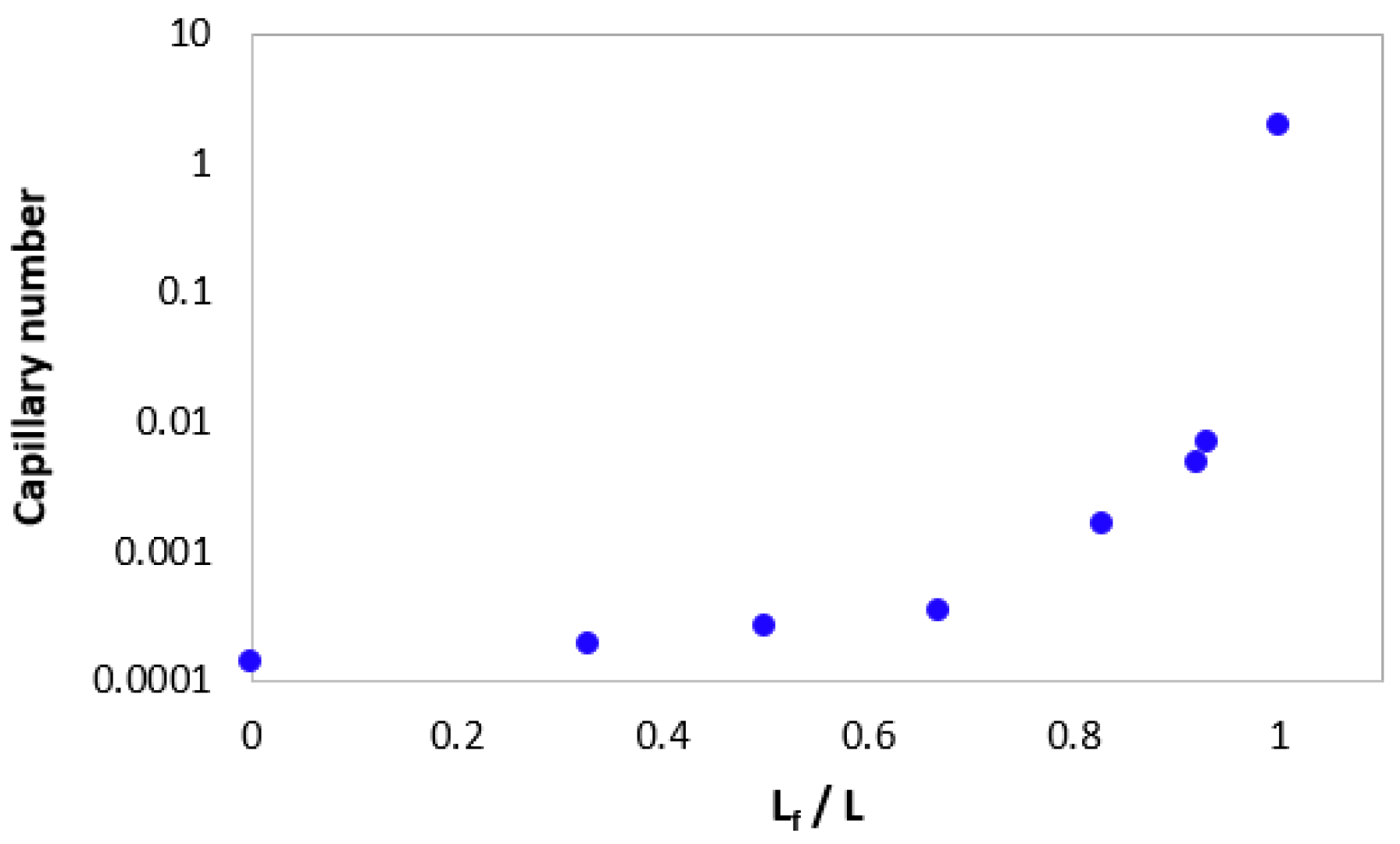

3.2. The Effect of lf/l

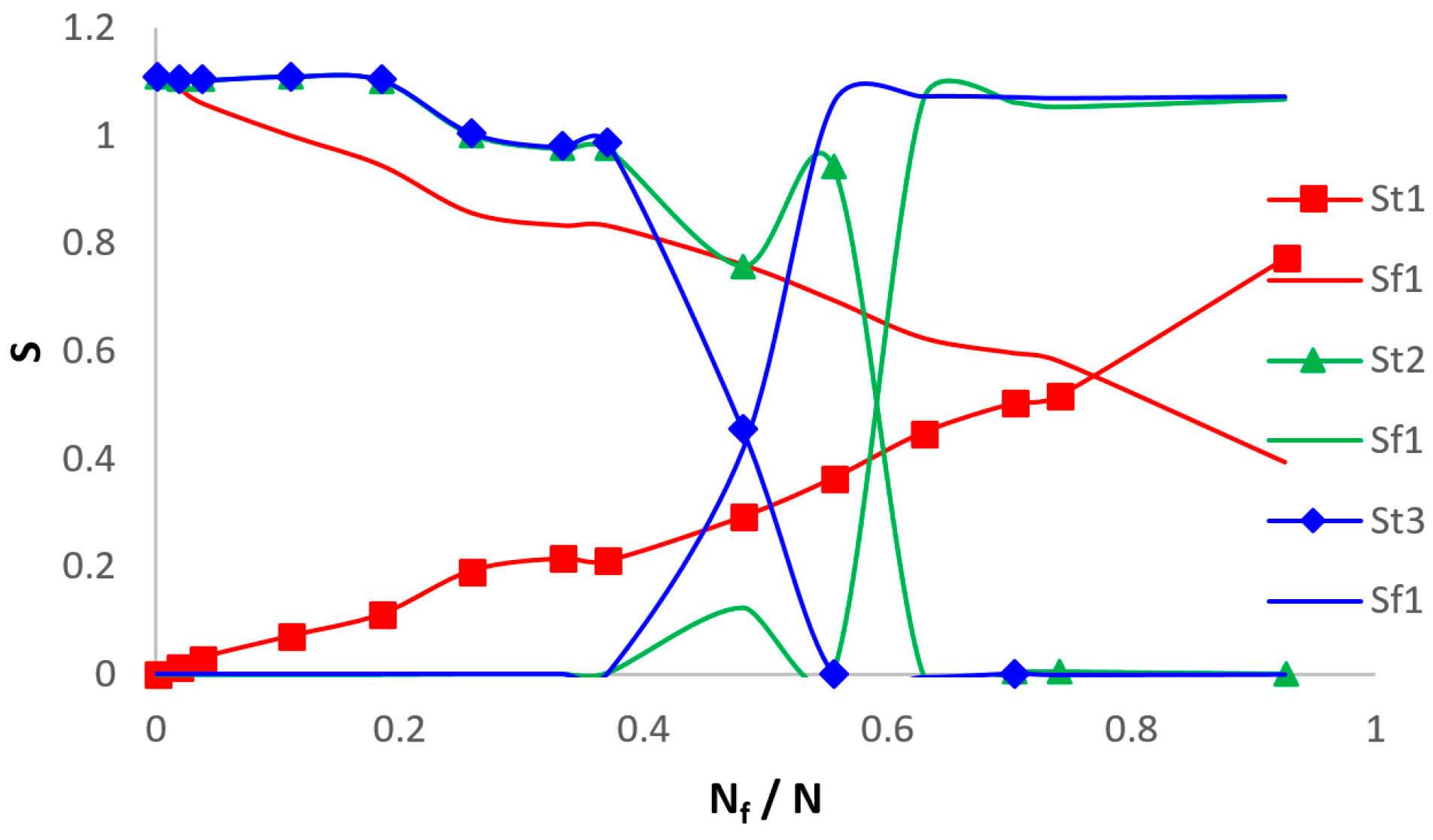

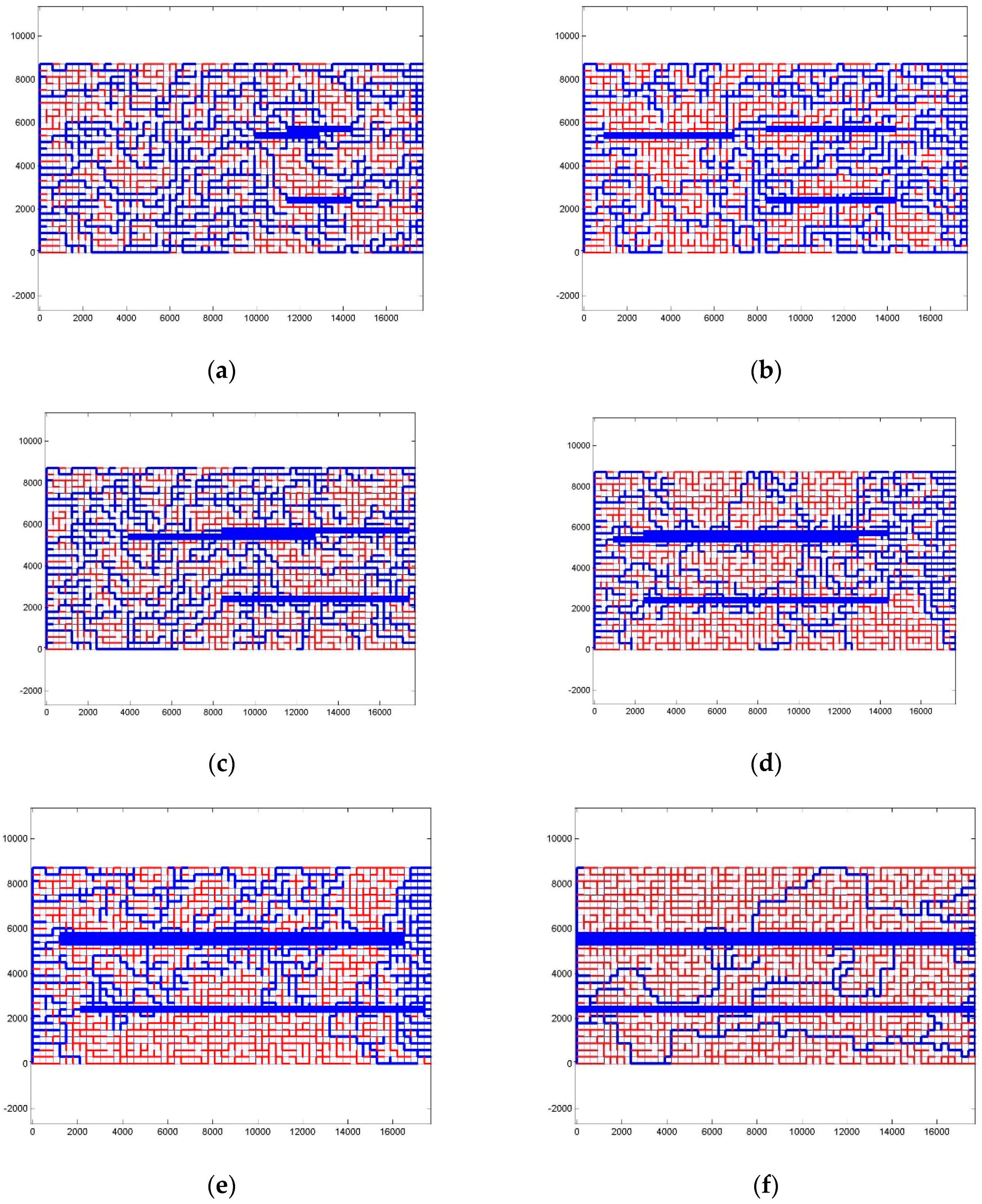

3.3. The Effect of Nf/N

3.4. The Effect of Direction

4. Conclusions

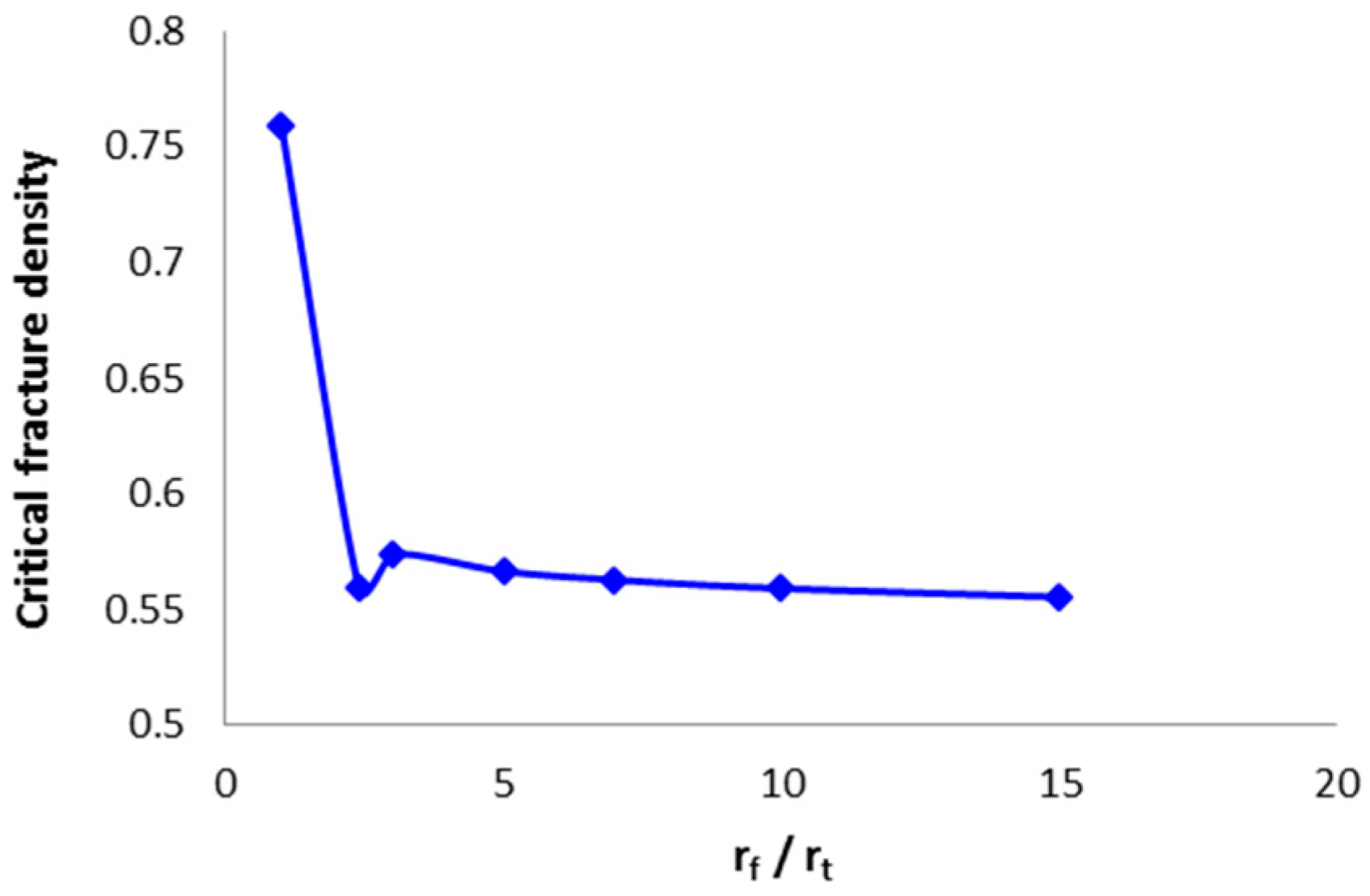

- (1)

- In the fractured pore-fracture network, matrix-dominant flow converts to fracture-dominant flow with the increase of fracture density and radius in the cases of single-phase flow. The critical fracture density for the transition decreases with the increase in the fracture radius.

- (2)

- The absolute permeability increases progressively with the increase in lf/l when lf/l < 0.8. Otherwise, it presents a sharp increase, at which point the water channeling occurs at lf/l = 1 and the displacement efficiency decreases to about 20%.

- (3)

- Both the fracture density and the pore structure of the matrix affect the absolute permeability and oil displacement efficiency. With the increase of fracture density, the absolute permeability increases rapidly and the oil displacement efficiency develops into three typical stages: when < 0.1, the oil displacement efficiency increases rapidly; when 0.1 < < 0.5, the oil displacement efficiency efficient changes slowly; and when > 0.5, the oil displacement efficiency decreases rapidly.

- (4)

- The absolute permeability increases when the fractures are parallel to the flow direction, while it decreases when the fractures are perpendicular to the flow direction. The existence of fractures can increase the displacement of the non-wetting phase, and the increase of the displacement efficiency is more pronounced when the fractures are parallel to the flow direction for Type I and Type II.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gaswirth, S.B.; Marra, K.R.; Cook, T.A.; Charpentier, R.R.; Gautier, D.L.; Higley, D.K.; Klett, T.R.; Lewan, M.D.; Lillis, P.G.; Schenk, C.J. Assessment of Undiscovered Oil Resources in the Bakken and Three Forks Formations, Williston Basin Province, Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota, 2013; US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2013.

- Jain, R. Natural resource development for science, technology, and environmental policy issues: The case of hydraulic fracturing. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2015, 17, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitrala, Y.; Moreno, C.; Sondergeld, C.; Rai, C. An experimental investigation into hydraulic fracture propagation under different applied stresses in tight sands using acoustic emissions. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2013, 108, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Lin, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y. Initiation, propagation, closure and morphology of hydraulic fractures in sandstone cores. Fuel 2017, 208, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, Z.; Winterfeld, P.; Ding, D.; Wu, Y.-S. In A multi-porosity, multi-physics model to simulate fluid flow in unconventional reservoirs. In Proceedings of the SPE Reservoir Simulation Conference, Montgomery, TX, USA, 20–22 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, J.F.; Reed, R.M.; Holder, J. Natural fractures in the Barnett Shale and their importance for hydraulic fracture treatments. AAPG Bull. 2007, 91, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, D.; Youssef, S.; Fleury, M.; Bekri, S.; Rosenberg, E.; Vizika, O. Improving the estimations of petrophysical transport behavior of carbonate rocks using a dual pore network approach combined with computed microtomography. Transp. Porous Media 2012, 94, 505–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Cheng, L.; Huang, S.; Wu, Y. A semi-analytical model for the flow behavior of naturally fractured formations with multi-scale fracture networks. J. Hydrol. 2016, 537, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, X.; Tian, C.; Shi, C.; Li, J.; Gang, H.; Hou, J.; Gao, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, P. Dynamic fractures are an emerging new development geological attribute in water-flooding development of ultra-low permeability reservoirs. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2015, 42, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Ma, D.; Wu, K. Measurement of three-phase relative permeabilities of various saturating histories and wettability conditions. In Proceedings of the International Symposium of the Society of Core Analysts, Aberdeen, UK, 27–30 August 2012; pp. 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, S.; Lu, W.; Liu, Q.; Leng, Z.; Li, T.; Liu, H.; Gu, H.; Xu, C.; Zhang, X.; Lu, X. Research on oil displacement mechanism in conglomerate using CT scanning method. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2014, 41, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatt, I. The network model of porous media. Petroleum Trans. AIME, 1956, 207, 144–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadpour, M.; Siavashi, M.; Doranehgard, M.H. Numerical simulation of two-phase flow in fractured porous media using streamline simulation and IMPES methods and comparing results with a commercial software. J. Cent. South Univ. 2016, 23, 2630–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadlelmula, F.; Mohamed, M.; Fraim, M.; He, J.; Killough, J.E. Discrete fracture-vug network modeling in naturally fractured vuggy reservoirs using multiple-point geostatistics: A micro-scale case. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, USA, 28–30 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Noetinger, B. A quasi steady state method for solving transient Darcy flow in complex 3D fractured networks accounting for matrix to fracture flow. J. Comput. Phys. 2015, 283, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Wang, Y.; Killough, J.E. Beyond dual-porosity modeling for the simulation of complex flow mechanisms in shale reservoirs. Comput. Geosci. 2016, 20, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, D.; Willemsen, J.F. Invasion percolation: A new form of percolation theory. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1983, 16, 3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, B.; Balberg, I. Percolation theory and its application to groundwater hydrology. Water Resour. Res. 1993, 29, 775–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joekar-Niasar, V.; Hassanizadeh, S.M. Uniqueness of specific interfacial area-capillary pressure-saturation relationship under non-equilibrium conditions in two-phase porous media flow. Transp. Porous Media 2012, 94, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joekar-Niasar, V.; Hassanizadeh, S. Analysis of fundamentals of two-phase flow in porous media using dynamic pore-network models: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 42, 1895–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Van Dijke, M.; Wu, K.; Couples, G.; Sorbie, K.; Ma, J. Stochastic pore network generation from 3D rock images. Transp. Porous Media 2012, 94, 571–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Lu, X. Comparisons of static, quasi-static and dynamic 3D porous media scale network models for two-phase immiscible flow in porous media. In New Trends in Fluid Mechanics Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 530–533. [Google Scholar]

- Ramstad, T.; Idowu, N.; Nardi, C.; Øren, P.-E. Relative permeability calculations from two-phase flow simulations directly on digital images of porous rocks. Transp. Porous Media 2012, 94, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lindquist, W. Dependence of pore-to-core up-scaled reaction rate on flow rate in porous media. Transp. Porous Media 2011, 89, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arns, C.H.; Bauget, F.; Limaye, A.; Sakellariou, A.; Senden, T.; Sheppard, A.; Sok, R.M.; Pinczewski, V.; Bakke, S.; Berge, L.I. Pore scale characterization of carbonates using X-ray microtomography. SPE J. 2005, 10, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joekar-Niasar, V.; Van Dijke, M.I.; Hassanizadeh, S. Pore-scale modeling of multiphase flow and transport: Achievements and perspectives. Transp. Porous Media 2012, 94, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bultreys, T.; Van Hoorebeke, L.; Cnudde, V. Multi-scale, micro-computed tomography-based pore network models to simulate drainage in heterogeneous rocks. Adv. Water Resour. 2015, 78, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barenblatt, G.; Zheltov, I.P.; Kochina, I. Basic concepts in the theory of seepage of homogeneous liquids in fissured rocks [strata]. J. Appl. Math. Mech. 1960, 24, 1286–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J.; Root, P.J. The behavior of naturally fractured reservoirs. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 1963, 3, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiroglou, C.D. A multi-scale approach to model two-phase flow in heterogeneous porous media. Transp. Porous Media 2012, 94, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, X.; Lu, X.; Zheng, W.; Liu, Q. A dual percolation model for predicting the connectivity of fractured porous media. Water Resour. 2016, 43, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibby, R. Mass transport of solutes in dual-porosity media. Water Resour. Res. 1981, 17, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, H.H.; Van Genuchten, M.T. Macroscopic representation of structural geometry for simulating water and solute movement in dual-porosity media. Adv. Water Resour. 1996, 19, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemonnier, P.; Bourbiaux, B. Simulation of naturally fractured reservoirs. State of the art-part 1-physical mechanisms and simulator formulation. Oil Gas Sci. Technol.-Revue de l’Institut Français du Pétrole 2010, 65, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemonnier, P.; Bourbiaux, B. Simulation of naturally fractured reservoirs. State of the art-part 2-matrix-fracture transfers and typical features of numerical studies. Oil Gas Sci. Technol.-Revue de l’Institut Français du Pétrole 2010, 65, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, S.-Z. The equivalent continuum media model of fracture sand stone reservoir. J. Chongqing Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2000, 23, 161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Q.; Yu, B. A fractal permeability model for gas flow through dual-porosity media. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 024316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Chen, H.; Xiao, S.; Cai, J. Research on relative permeability of nanofibers with capillary pressure effect by means of fractal-monte carlo technique. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 17, 6811–6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noetinger, B.; Jarrige, N. A quasi steady state method for solving transient Darcy flow in complex 3D fractured networks. J. Comput. Phys. 2012, 231, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Farah, N.; Bourbiaux, B.; Wu, Y.; Mestiri, I. Simulation of matrix-fracture interaction in low-permeability fractured unconventional reservoirs. In Proceedings of the SPE Reservoir Simulation Conference, Montgomery, TX, USA, 20–22 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Noetinger, B.; Estebenet, T. Up-scaling of double porosity fractured media using continuous-time random walks methods. Transp. Porous Media 2000, 39, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerbi, C.; Fourno, A.; Noetinger, B.; Delay, F. A new estimation of equivalent matrix block sizes in fractured media with two-phase flow applications in dual porosity models. J. Hydrol. 2017, 548, 508–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Qu, X.; Wang, C.; Lei, Q.; Cheng, L.; Yang, Z. Natural fracture distribution and a new method predicting effective fractures in tight oil reservoirs in Ordos Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2016, 43, 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahle, H.K.; Celia, M.A. A dynamic network model for two-phase immiscible flow. Comput. Geosci. 1999, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.G.; Deo, M.D. Finite element, discrete-fracture model for multiphase flow in porous media. AIChE J. 2000, 46, 1120–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.; Slobod, R. Displacement of oil by water-effect of wettability, rate, and viscosity on recovery. In Proceedings of the Fall Meeting of the Petroleum Branch of AIME, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–5 October 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, R.L.; Healy, R.N. Some physicochemical aspects of microemulsion flooding: A review. Improv. Oil Recovery Surfactant Polym. Flooding 1977, 383–437. [Google Scholar]

- AlQuaimi, B.; Rossen, W. New capillary number definition for displacement of residual nonwetting phase in natural fractures. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fracture Density Nf/N (0~1) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

| = c1 = c2 | = c1 × t1 = c2 | = c1 × t2 = c2 |

| Permeability Classification | Throat Radius (Normal Distribution) | Porosity of the Matrix (%) | Absolute Permeability of the Matrix (mD) | Oil Displacement Efficiency of the Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I (50~10 mD) | 0.1~20 μm, = 6, = 10 μm | 6.10 | 18.7 | 0.38 |

| Type II (10~1 mD) | 0.1~20 μm, = 6, = 8 μm | 4.38 | 2.23 | 0.64 |

| Type III (1~0.1 mD) | 0.1~20 μm, = 6, = 5 μm | 3.06 | 0.76 | 0.37 |

| Cases | K/mD Type I | K/mD Type II | K/mD Type III |

|---|---|---|---|

| No fracture | 18.8 | 2.2 | 0.8 |

| Parallel to the flow direction | 50.0 | 8.3 | 0.7 |

| Perpendicular to the flow direction | 41.4 | 5.2 | 2.6 |

| Multi-direction | 37.8 | 5.1 | 0.8 |

| 30° with the flow direction | 9.8 | 4.3 | 0.2 |

| Cases | Type I | Type II | Type III |

|---|---|---|---|

| No fracture | 0.38 | 0.64 | 0.37 |

| Parallel to the flow direction | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.53 |

| Perpendicular to the flow direction | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.54 |

| Multi-direction | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.53 |

| 30° of the flow direction | 0.73 | 0.66 | 0.56 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Lu, X.; Liu, Q. Study on Flow in Fractured Porous Media Using Pore-Fracture Network Modeling. Energies 2017, 10, 1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/en10121984

Liu H, Zhang X, Lu X, Liu Q. Study on Flow in Fractured Porous Media Using Pore-Fracture Network Modeling. Energies. 2017; 10(12):1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/en10121984

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Haijiao, Xuhui Zhang, Xiaobing Lu, and Qingjie Liu. 2017. "Study on Flow in Fractured Porous Media Using Pore-Fracture Network Modeling" Energies 10, no. 12: 1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/en10121984