1. Introduction

In recent years, the interest in air infiltrations has significantly grown. The uncontrolled intake access through the envelope of buildings generates a series of problems that affect its occupants [

1]: higher energy consumption, lack of thermal comfort, entry of pollutants and odours, noise, inadequate functioning of ventilation systems, less protection against fire, etc.

There are numerous studies that have been carried out in Northern Europe, USA, and Canada for decades [

2]. However, in Mediterranean countries there is still a lack of knowledge in this area [

3]. Some field studies have been carried out to characterize the behaviour of the envelope of residential buildings concerning infiltration (

Table 1):

In the south of Italy, an experimental study [

4] was carried out in 20 residential buildings of different periods (1810–2010), climatic zones, and typologies (cottages, terraced houses, apartments, and large buildings). The study focused on the impact of infiltrations on energy consumption and thermal comfort, analysing the influence of several parameters: net floor area, envelope area, internal volume, typology, type of window frames, and year of construction.

Another study in Italy [

5] analysed the airtightness of a three-story building of the 1970s recently renovated with six apartments to know the influence of air leakage on energy losses and indoor air quality. Repeated tests sealing different elements revealed the influence of each component on the total infiltration rate.

Sfakianaki et al. [

6] conducted a study in 20 single-family homes in the Attica area, Greece. Both the tracer gas decay and pressurization methods were used. In this way, the cases were classified into three categories according to EN ISO 13,790 [

14] and the influence of different parameters on the global infiltration rate was statistically evaluated.

In Coimbra, Portugal [

3], four retrofitted and original buildings of the historic centre were studied. Three of them were multi-family buildings and one was a detached house. The objective was to know the air change rate (ACH) of the chosen sample and to establish the minimum ACH to maintain good indoor air quality and acceptable thermal behaviour. Another more extensive testing campaign in Portugal [

7] analysed 49 apartments in two social housing neighbourhoods in order to know the relationship between the behaviour of the users of the dwellings and their airtightness and ventilation. One of the neighbourhoods had recently been rehabilitated. Tests were also carried out in an apartment to find out the individual impact of different elements on the airtightness of the whole envelope (window frame, self-regulated air inlets, mechanical extraction in kitchens, fixed air inlets in the laundry, and mechanical fan in the bathroom).

A study in Osijek, Croatia, [

8] obtained a database with airtightness test results in 58 residential units. The sample was considered representative in terms of year of construction after finding a relationship between the elements of the sample and the statistical data of residential buildings in Croatia. The purpose was to establish a method for predicting the airtightness of the envelope applying neural networks, which has been subsequently validated [

15,

16].

In Turkey [

9], another study was carried out after the detection of problems in dwellings such as inadequate air conditioning and ventilation or condensation. Airtightness tests were conducted in 52 newly built unoccupied homes to analyse the behaviour of the envelope and to proceed with a possible revision of the regulations.

In the case of Spain, only partial studies have been carried out so far to characterize the airtightness of the envelope of the housing stock. None of them has covered the entire geography of the country. The study with the largest number of tests fulfilled was conducted in recently built dwellings in northern Spain [

10] to determine the level of infiltration in residential buildings and to establish the determining factors. Also, in northern and central Spain, Meiss and Feijó-Muñoz [

11] developed a procedure to evaluate the excess energy consumption caused by air infiltration, analysing 13 homes in residential buildings. The lack of airtightness in Spain was estimated to represent between 10.5% and 25.4% of the energy demand in winter in buildings built under current regulations [

17].

Several social housing units in Madrid and Seville were analysed to determine the degree of airtightness and indoor air quality [

12]. The sample was chosen paying attention to the representativeness of the architectural and construction typologies used in the period 1940–1980 and presented different degrees of retrofitting of the envelope. The airtightness of the envelope in residential buildings at the beginning of the 21st century in the south of Spain has also been characterized [

13]. The selection of cases to be analysed in each building was made with a stratified probabilistic design.

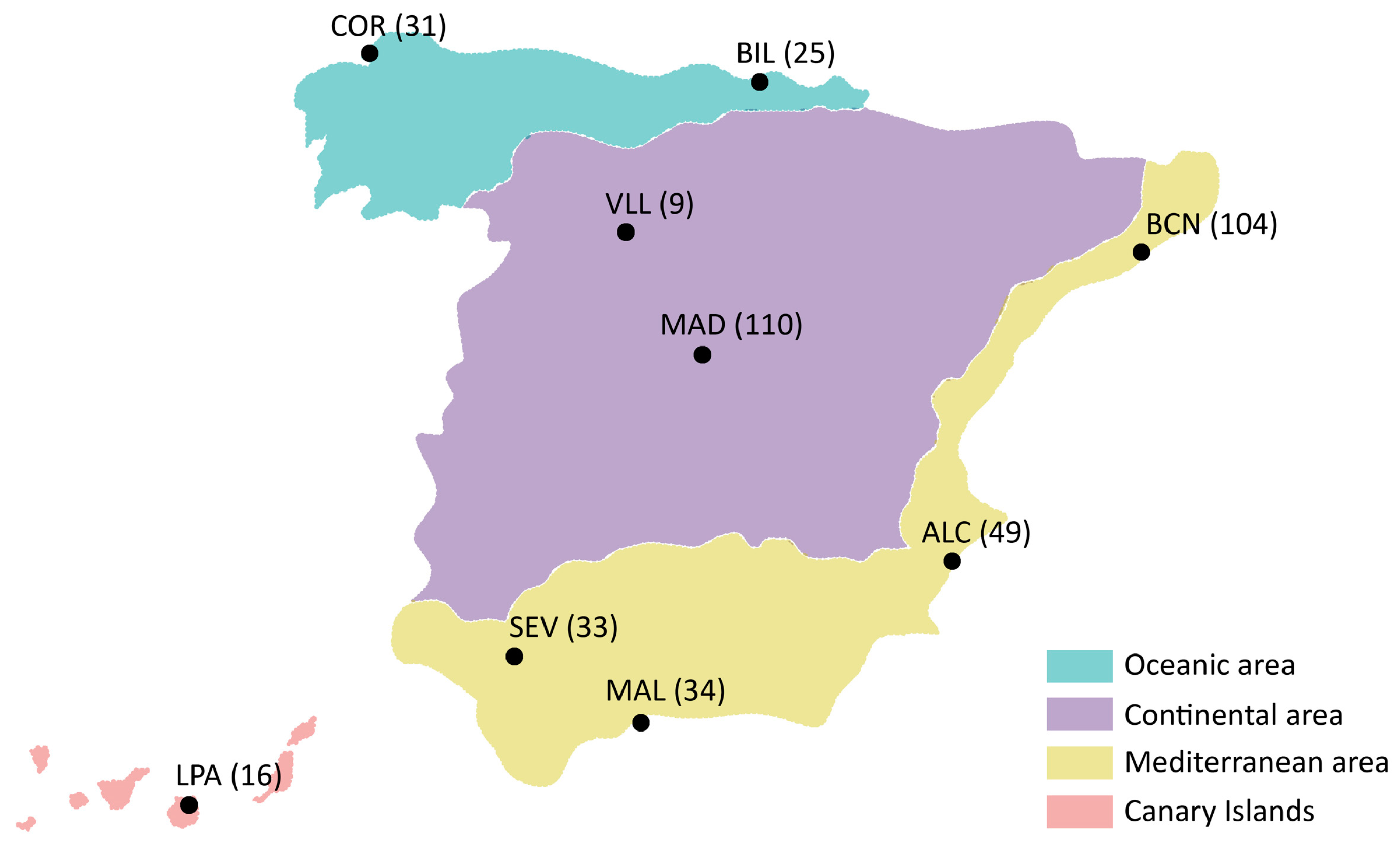

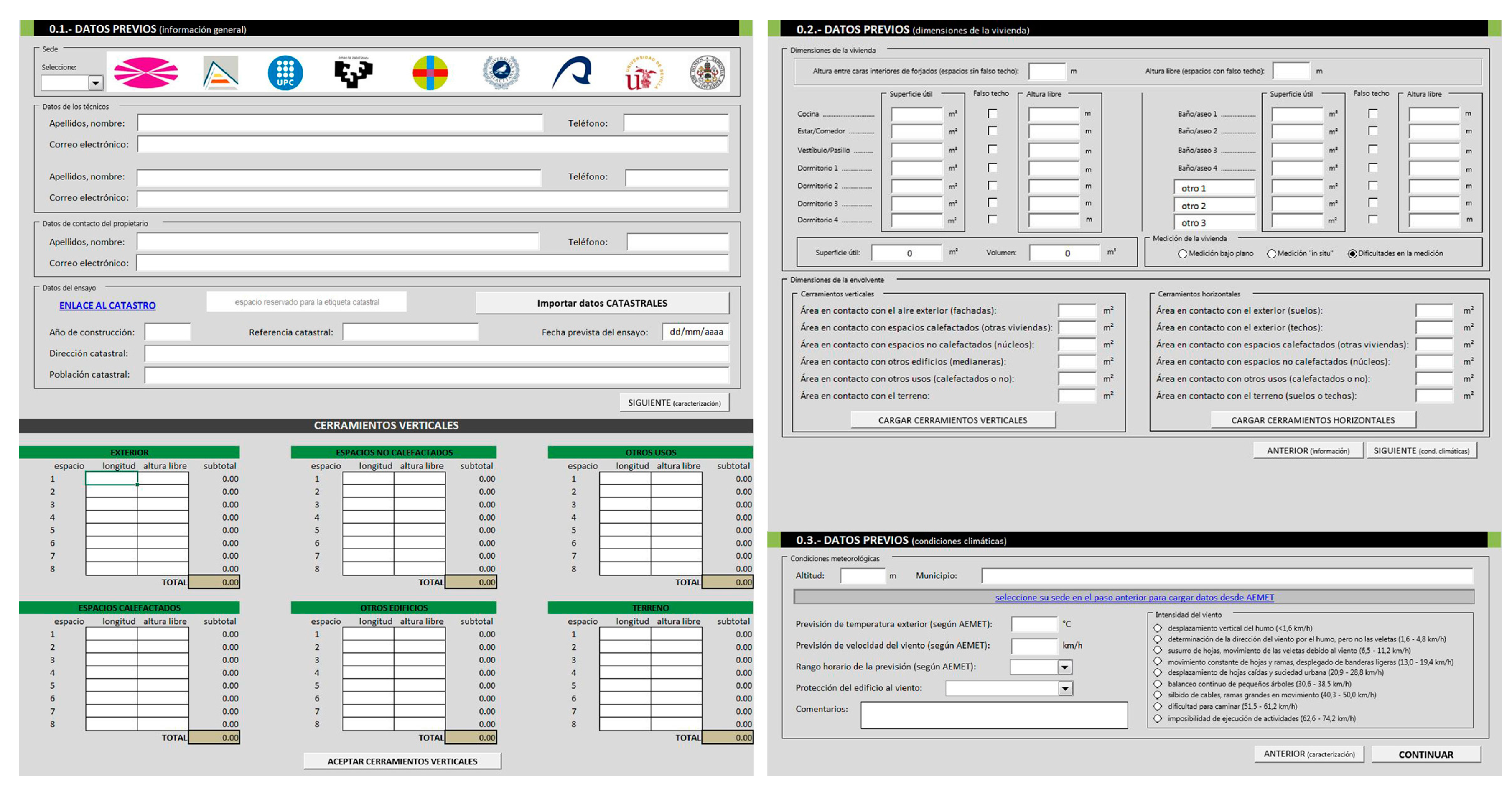

The objective of this work is to establish a rigorous and simple methodology in order to carry out a characterization of the envelope of residential buildings in Spain in terms of airtightness, through coordinated testing campaigns. A broad database of 411 cases that collects characterization information and results is being created. In a later phase, the analysis of the data under a unified procedure and criteria will be guaranteed. In this sense, it will be possible to know the impact that different factors have on airtightness, as well as the infiltration rates corresponding to the most widespread constructive solutions in Spain.

This methodology has been conceived in such a way that it is easily applicable to other countries that intend to evaluate the energy impact of air leakage of existing buildings.

Regulations in Spain

The European Directive on the energy performance of buildings [

18] is committed to the generalization of nearly-zero energy buildings (nZEB) by 2020. In response to it, many countries have been incorporating limitations in their regulations regarding the airtightness of the envelope [

19] since the beginning of the 2000s.

However, in Mediterranean countries with a temperate climate, where ventilation has traditionally been done in a natural and manually controlled way, infiltrations have been part of the air supply and have compensated the lack of regulation of specific controlled ventilation systems [

13].

In Spain, after the oil energy crisis in the 70s, the building regulations NBE-CT-79 [

20], relating to thermal conditions of buildings, tended to increase thermal insulation, achieving an improvement in the energy performance of buildings. NBE-CT-79 also affected indoor air quality as a consequence of the lack of ventilation. To give an answer to this problem, in 2006 regulations of the Technical Building Code (CTE) DB HS3 [

21] were approved. This document implemented specific ventilation requirements and proceedings to ensure adequate indoor air quality, establishing minimum ventilation flows.

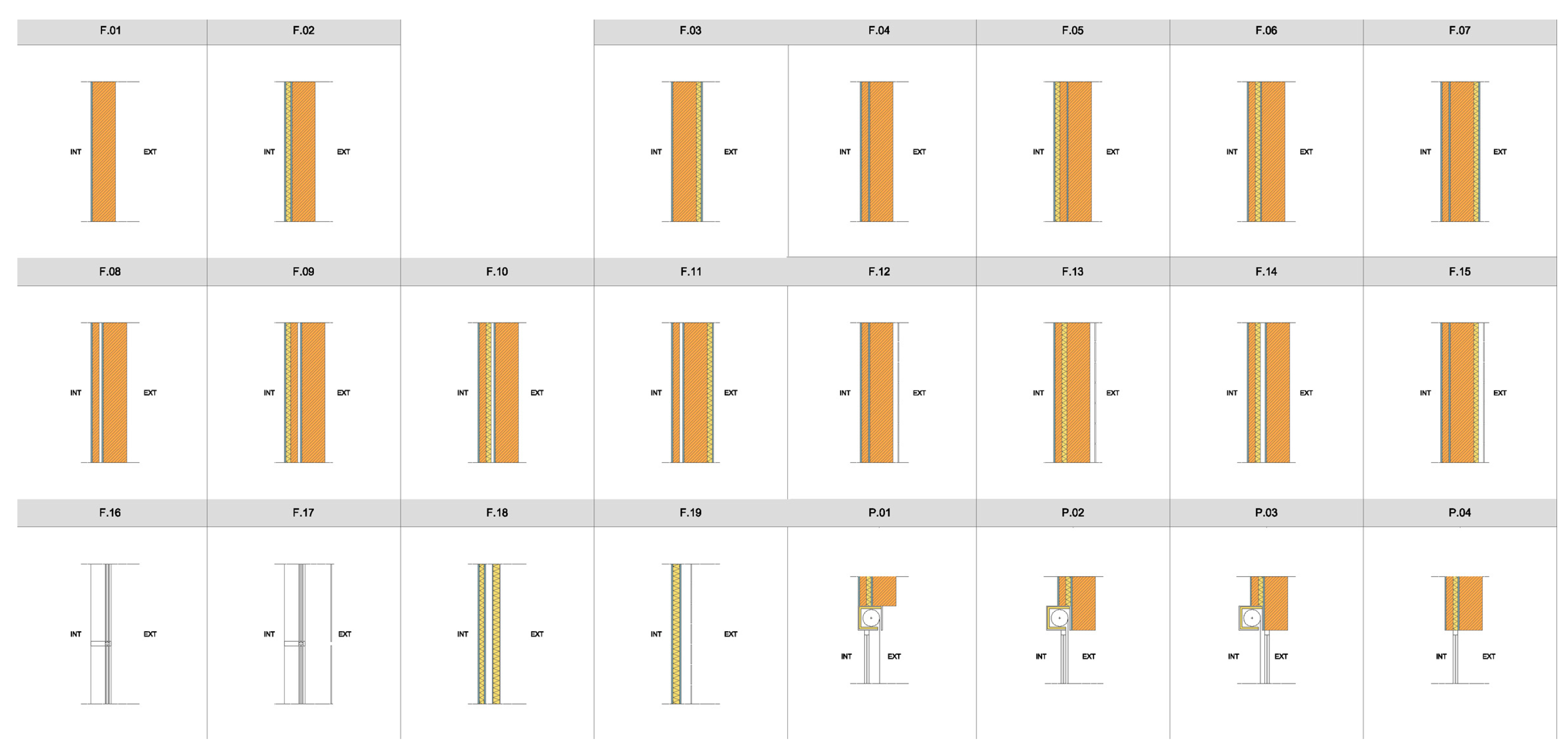

The current version of the CTE [

21], in spite of not contemplating a minimum requirement of global airtightness of the envelope, gives the option to consider the equivalent infiltration area as part of the ventilation opening area. In this way, using technical specifications tables or minimum values of airtightness established for each type of window (

Table 2) it is possible to adjust the required flow rates. However, the obtaining of a precise value for the entire enclosure considering not only the airtightness of its elements separately, but also the encounters of each solution, would be necessary. In any case, the lack of knowledge of airtightness values results in the oversizing of the ventilation systems.

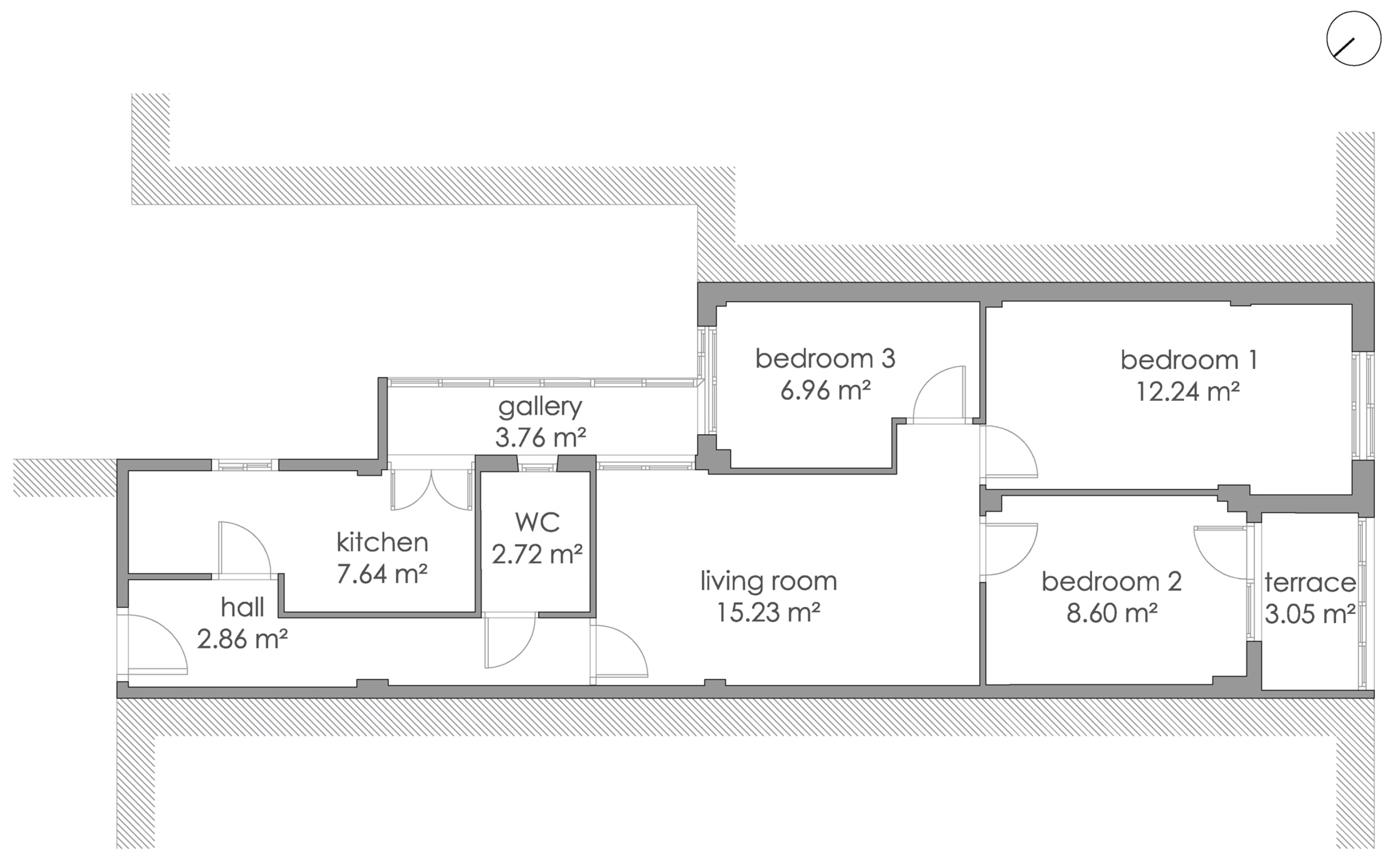

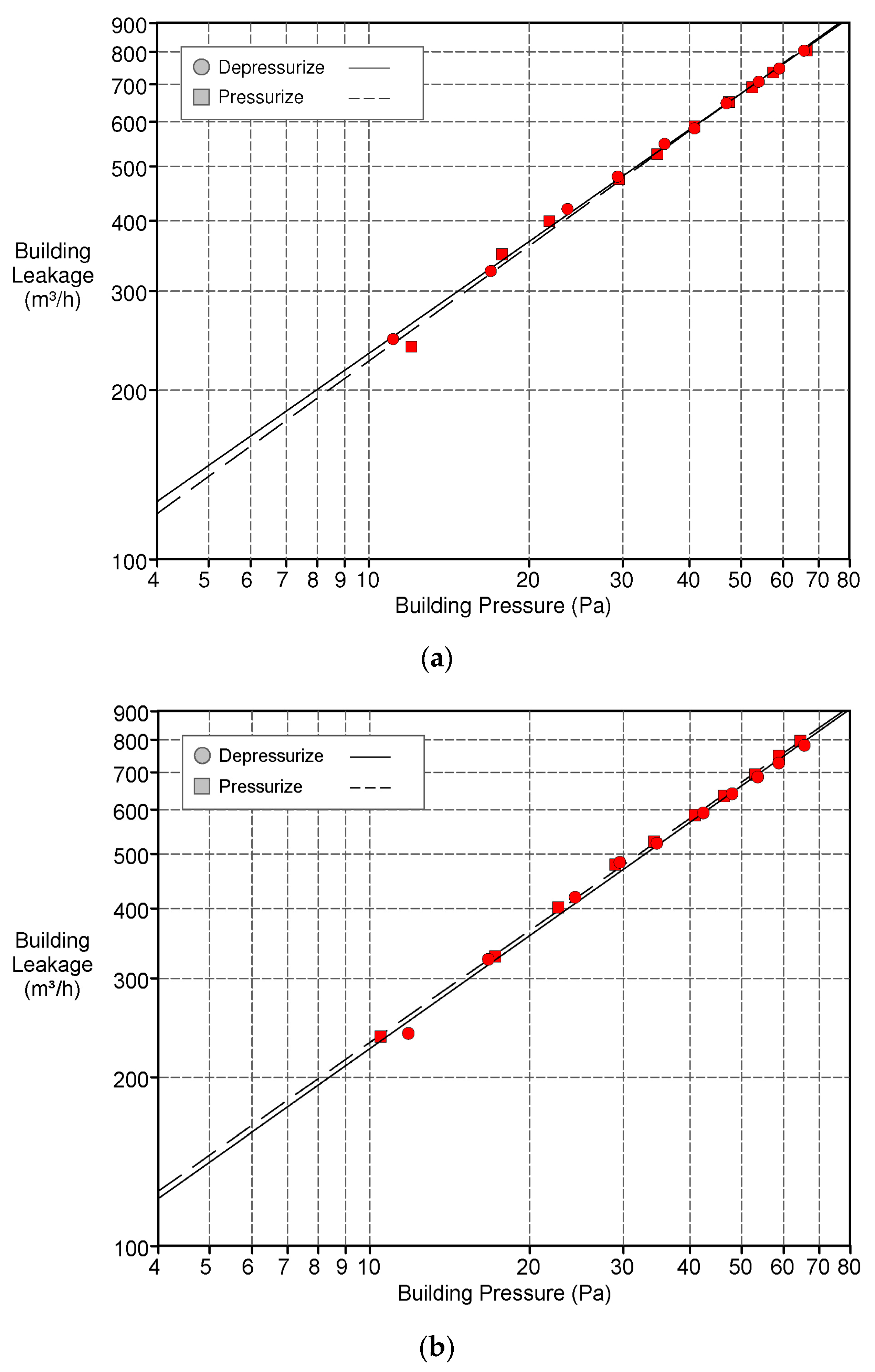

3. Case Study

A case study is presented in order to show the implementation of the designed methodology. An apartment located in the city centre of Valladolid (

Figure 8) has been chosen due to its representativeness of the residential building stock in Spain (case 09683460651630036). The climate of Valladolid belongs to the “Continental” area of the country and it is classified by CTE as D2 area.

The building was constructed in 1968, before regulations in Spain considering energy losses were implemented. The building consists of 9 floors and an attic. The apartment is on the ninth floor and has a south orientation in its main façade to Padilla Street and a secondary façade to a wide internal courtyard with east orientation (

Figure 9). All the specifics are detailed in

Table 7.

3.1. Results and Discussion

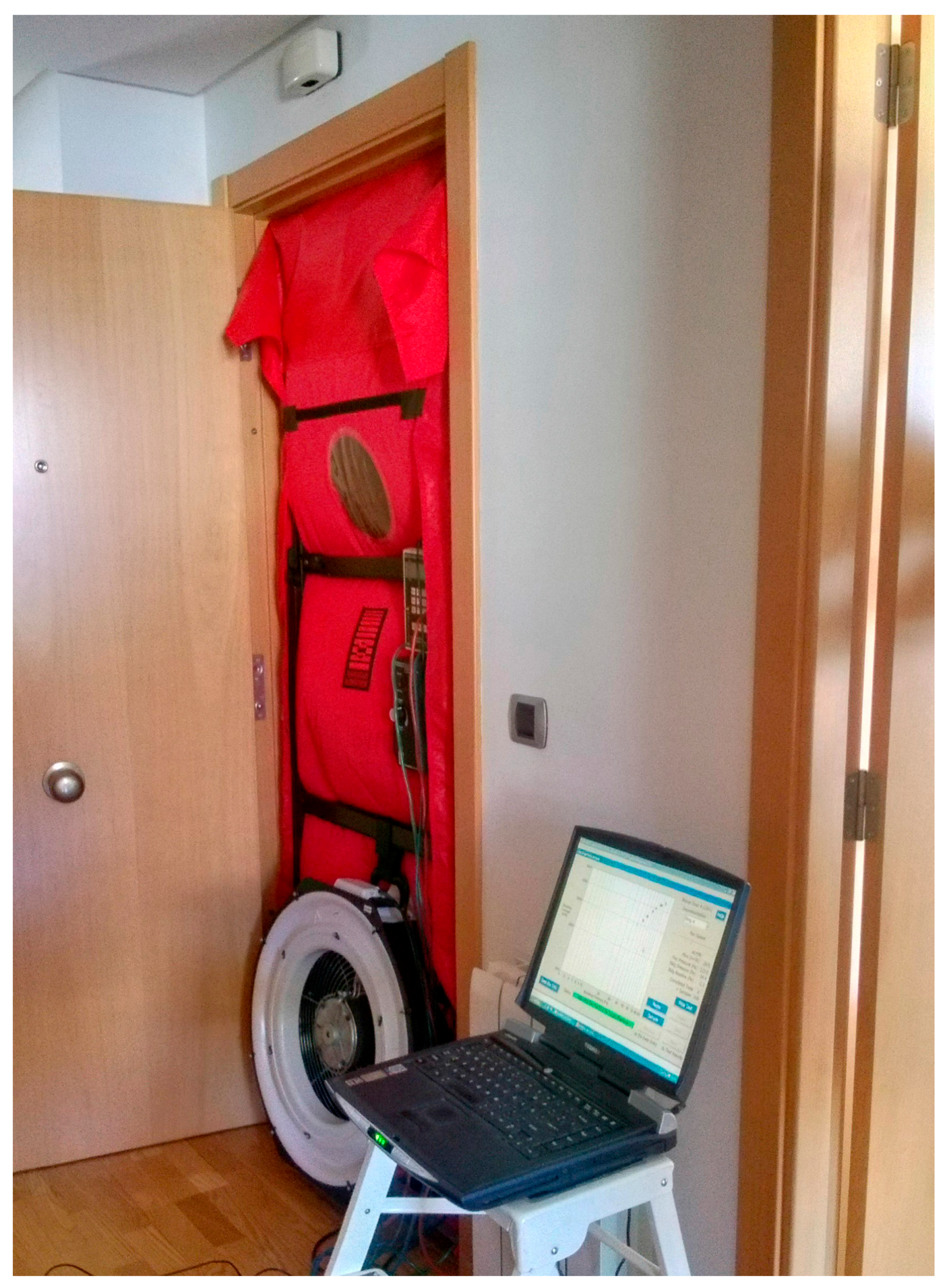

In order to measure the airtightness of the dwelling, blower door tests are carried out with an automated performance testing system and following the project protocols (

Figure 10). Tests were carried out in February 2017 with the environmental conditions described in

Table 8. Test results are detailed in

Table 9.

The overall uncertainty in the parameters obtained with the test using standard equipment remains below 15% in most cases [

4,

35,

45] under calm conditions.

The mean air change rate of the dwelling for Method B at 50 Pa (n50) is 4.38 h−1 and the mean air permeability rate at 50 Pa (q50) is 2.9 m3/m2·h.

The exponent n has a typical value close to 0.67. Consequently, the flow is neither fully turbulent nor dominated by laminar characteristics and the shape of leakage paths cannot be clearly defined.

There is barely any difference between the results obtained for Methods A (test of the building in use) and B (test of the building envelope). This can be explained because there are no mechanical supply or exhaust systems nor adjustable openings. There is only one natural ventilation grid in the kitchen, which was left open for the purposes of Method A and sealed for Method B.

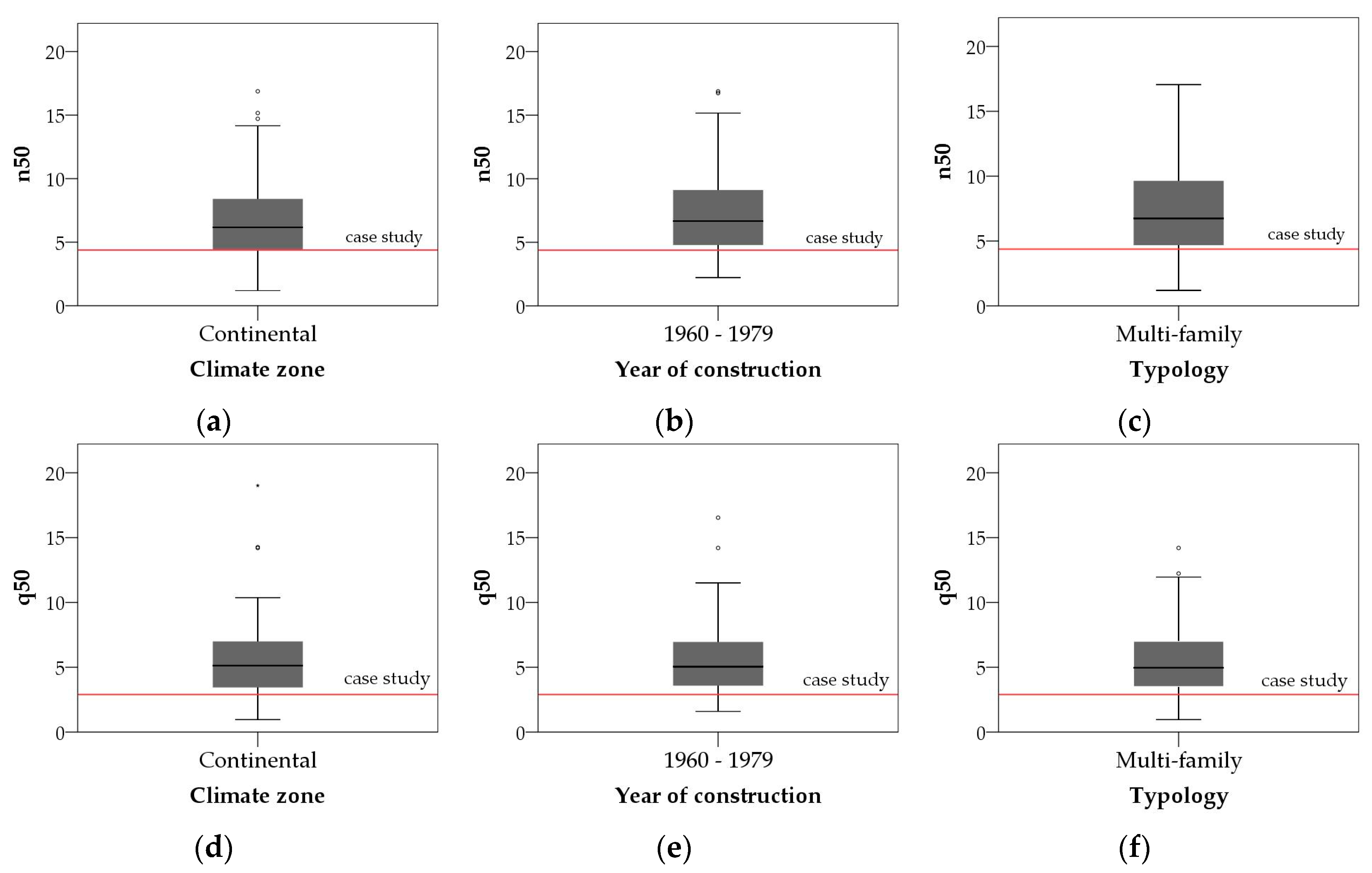

3.2. Comparison of the Results

The case study results are compared to preliminary results of 343 buildings tested in the database (

Table 10). Building airtightness is expressed by either the air change rate (n

50) or the air permeability rate (q

50).

As a preliminary analysis of the results, the control variables used to design the sample were studied: climate zone, year of construction, and typology.

Figure 11 represents graphically the comparison between the case study results and the database results for Method B concerning dwellings from the same climate zone (Continental), built within the same period (1960–1979) and dwellings with the same typology (multi-family housing).

Although there is a wide spread of the values obtained from the database, the mean values according to the chosen parameters do not differ in a meaningful way. It seems clear the fact that significantly better results have been obtained for the case study dwelling than the general trend of the database.

According to ISO 13790 [

14] the case-study dwelling has a “medium airtightness level”, having a value within the range of 2–5 h

−1. However, the mean n

50 value for multifamily dwellings of the database is 7.26 h

−1, which, according to ISO 13790 [

14], corresponds to a “low airtightness level”.

When compared to regulations in other European countries, the case study dwelling would comply with UK (q

50 < 10 m

3/m

2·h) and Ireland (q

50 < 7 m

3/m

2·h) or Czech Republic (n

50 < 4.5 h

−1) regulations but not with German regulations nor Polish recommendations (n

50 < 3 h

−1) for new buildings [

49]. The comparison with French regulations has not been made since its indicator is measured at 4 Pa and a direct translation of the results would not be accurate.

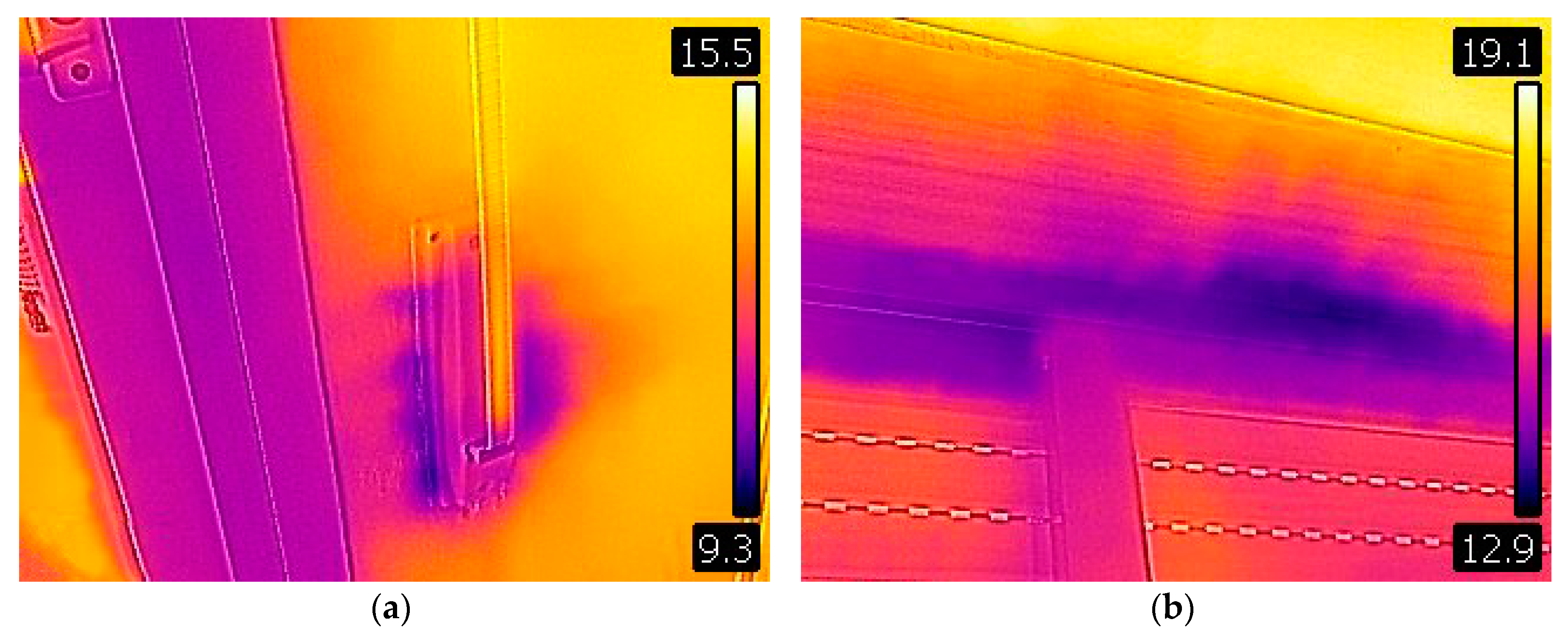

3.3. Leakages Location

To determine infiltration locations and distribution, thermal imaging was undertaken during the depressurization stage. Since there was a great temperature difference between the inside and the outside of the dwelling leakage points were easily visualized. Most leakages were located in window frames and shutter boxes (

Figure 12).

4. Conclusions

A methodology has been developed to investigate the airtightness of the architectural envelope of the existing residential stock in Spain through an experimental study carried out throughout the Spanish geography. Considering a proportional quota sampling scheme, a representative number of 411 cases has been selected. In this way it is possible to extrapolate the results to other Spanish residential buildings. The sample includes different typologies, construction years, and climatic zones. The study will allow the creation of an extensive database and the identification of the factors that have a greater impact on airtightness and the infiltration rates of typical constructive solutions. The methodology has been conceived in such a way that it can be applied to other countries where there is no data regarding the airtightness of the envelope in residential buildings.

A case study in Valladolid has been presented in order to show an example of the implementation of the methodology. Airtightness results are compared to mean values obtained from the database, considering the control variables used to design the sample: climate zone, year of construction, and typology. Results obtained indicate that the dwelling has a medium airtightness level, significantly higher than the mean values obtained from the database. Leakages at the case study were located mainly around window joints and frames and shutter boxes.

Further work will include a deep analysis of the complete dataset obtained during the test campaigns in order to establish infiltration rates for typical Spanish constructive solutions, the impact of different parameters on the envelope permeability, and the impact of infiltrations on the ventilation and energy performance of dwellings.