Optimal Fixed Bed Reactor Network Configuration for the Efficient Recycling of CO2 into Methanol

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The heuristic approach, which relies on intuition and engineering experience and thought.

- The physical insight approach, which is based on exploiting basic physical principles.

- The optimization approach, which depends on mathematical programming techniques.

2. Reactor modeling

2.1. Single reactor modeling

| Quantity | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of tubes [-] | 2962 |

| Length of reactor [m] | 7.022 |

| Bulk density of bed [kg/m3] | 1132 |

| Void fraction of bed [m3/m3] | 0.39 |

| Internal radius of tubes [mm] | 38 |

| Catalyst diameter [mm] | 5.4 |

2.2. Auxiliary equations

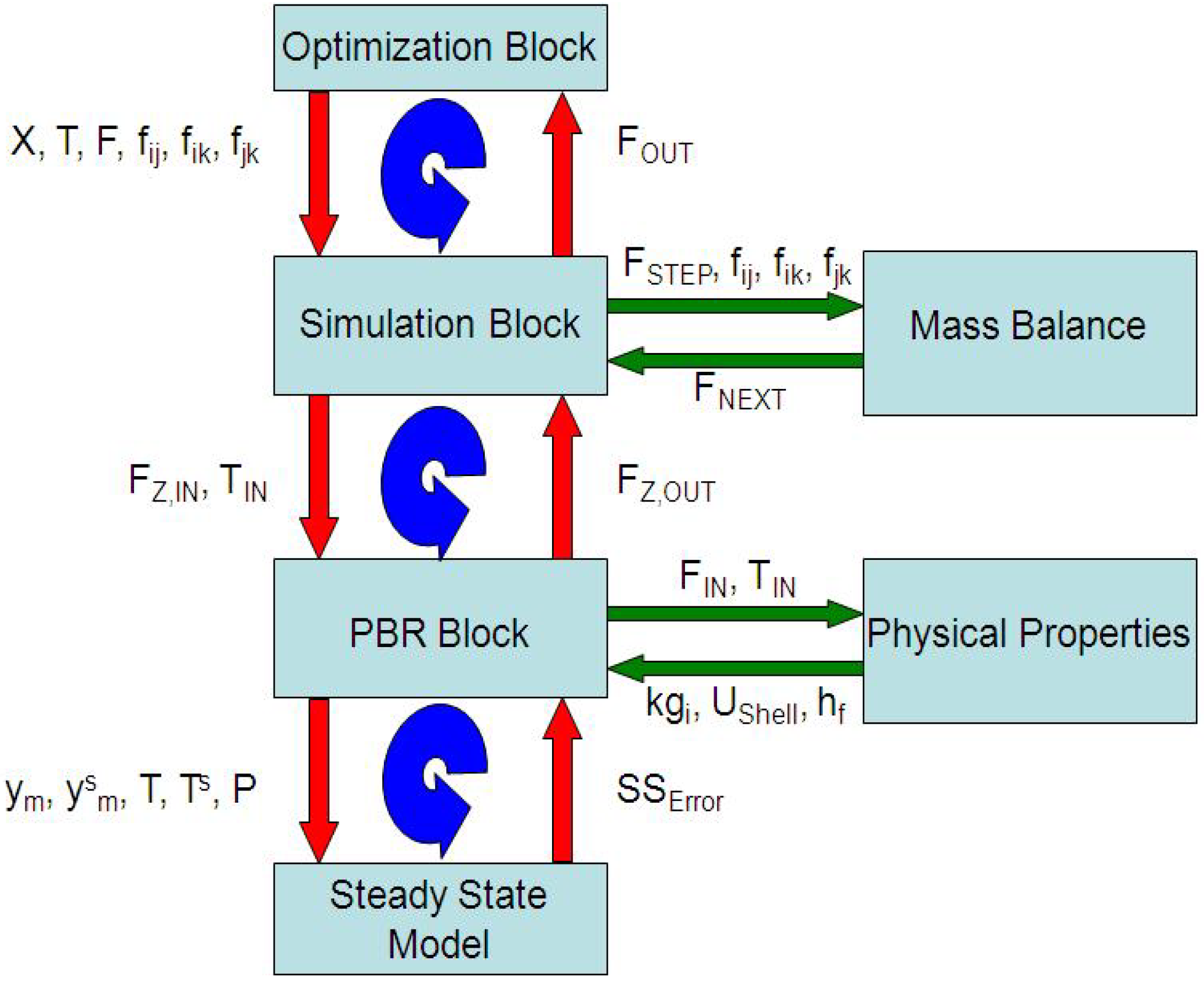

2.3. Simulation

| Plant data (ton/day) | Model (ton/day) | |

|---|---|---|

| 255.2 | 250.01 |

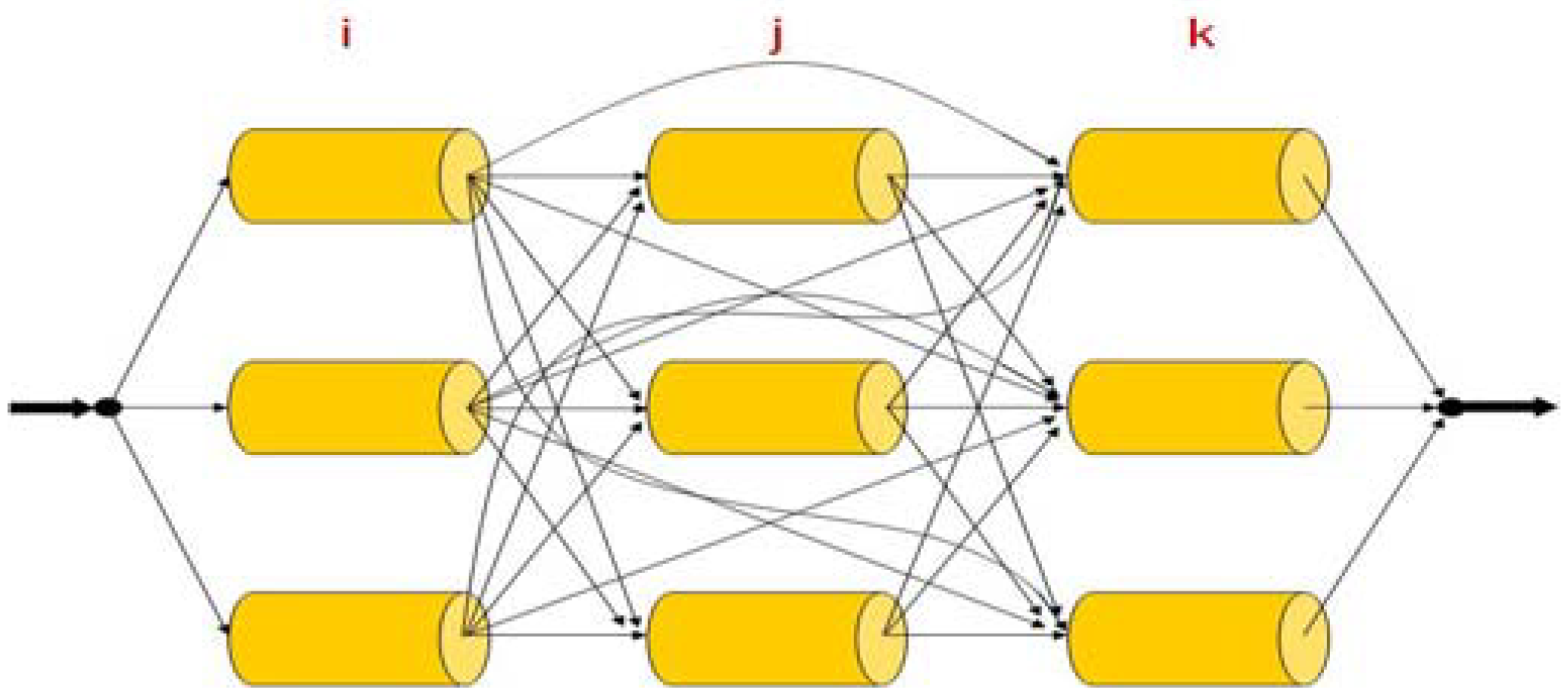

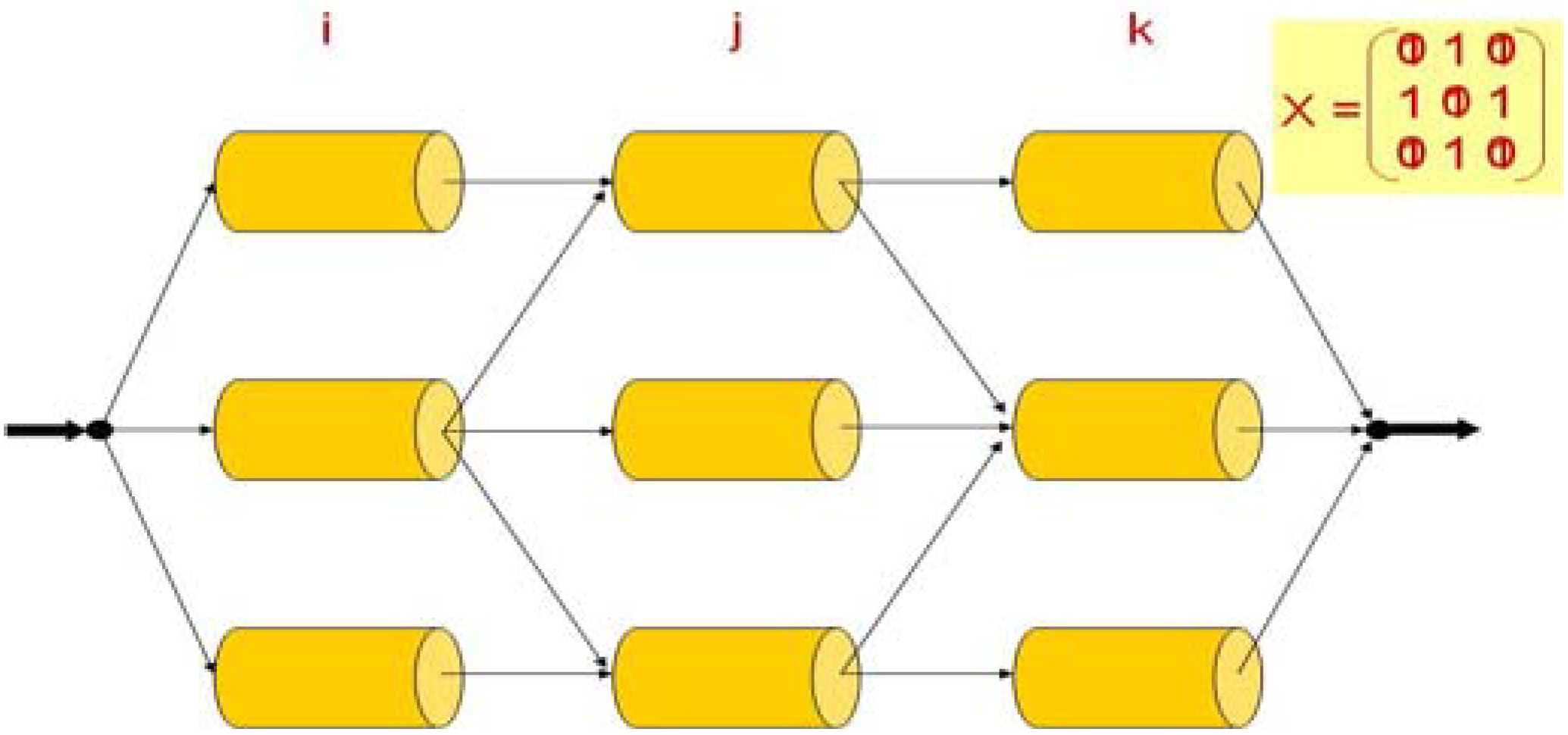

3. Superstructure

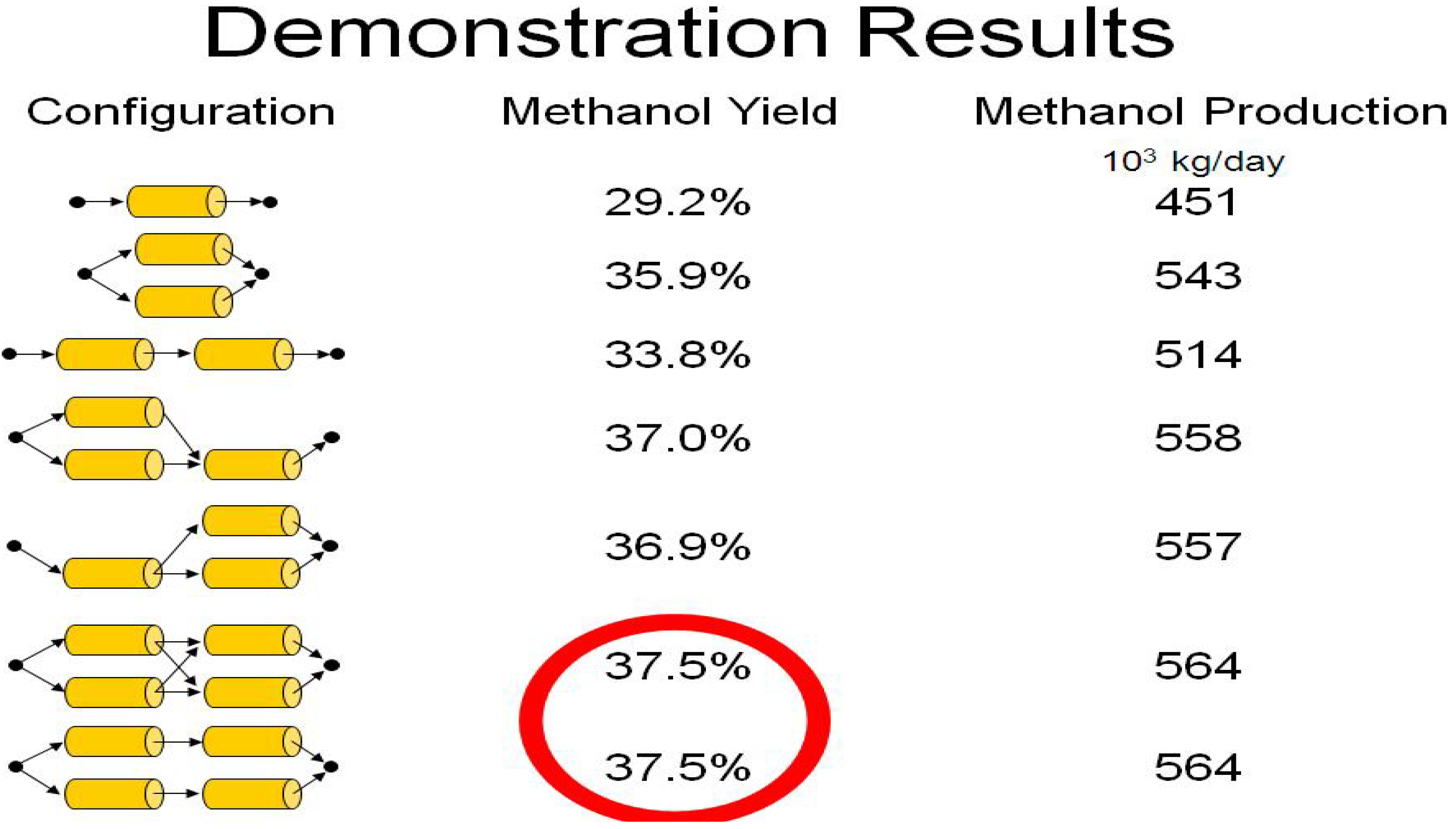

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Notation:

| [m2r] | cross area of each tube | |

| [m2s.m-3r] | external particle surface area per unit of reactor volume | |

| a | [-] | activity of catalyst |

| [j.mole-1] | specific heat of the gas at constant pressure | |

| [j.mole-1] | specific heat of the solid at constant pressure | |

| [mole.m-3g] | total concentration | |

| [mr] | tube inside diameter | |

| [mole.s-1] | total molar flow per tube | |

| [W.m-2s.K-1] | gas-solid heat transfer coefficient | |

| [m.s-1] | mass transfer coefficient for component i | |

| N | number of components | |

| Nr | number of reactions | |

| R | [j.mol-1.K-1] | universal gas constant |

| [mole.kg-1s.s-1] | reaction rate of component i | |

| T | [K] | bulk gas phase temperature |

| [K] | temperature of gas on the solid surface | |

| [K] | temperature of boiling water in the shell side | |

| [K] | reference temperature | |

| t | [s] | time |

| [W.m-2r.K-1] | boiling water-gas overall heat transfer coefficient | |

| [-] | bulk gas phase mole fraction for component i | |

| [-] | mole fraction of ith component in the solid phase | |

| z | [m] | axial reactor coordinate |

Greek letters:

| ΔHf,i | [j.mol-1] | enthalpy of formation of component i | |

| εB | [m3g.m-3r] | void fraction of catalytic bed | |

| εS | [m3g.m-3s] | solid particles’ void fraction | |

| ρB | density ( kg/m3 ) | ||

Superscripts and subscripts:

| 0 | inlet conditions |

| 0 | initial conditions |

References and Notes

- Kirk-Othmer. Concise Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology; J. Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, U.S.A., 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Merk. The Merck Index, 13th Edition ed; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, U.S.A., 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Methanex. 2007. www.methanex.com (accessed on April 1st, 2009).

- Lange, J.P. Methanol synthesis: a short review of technology improvements. Catal. Today 2001, 64, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lurgi. Integrated low pressure methanol process; Technical report; Gas Chemie BmbH: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lovik, I. Modelling, Estimation and Optimization of the Methanol Synthesis with Catalyst Deactivation. PhD Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Santacesaria, E.; Tesser, R.; Serio, M.D.; Guida, M.; Gaetano, D.; Garcia Agreda, A.; Cammarota, F. Comparing Different Reactor Configurations for the Reduction of Free Acidity in raw Materials for Biodisel Production. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 8355–8362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, G.; Elkamel, A.; Lohi, A.; Jahanmiri, A.; Rahimpor, M.R. Hybrid model formulation for the unsteady state simulation of a packed bed reactor for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Chem. Eng. J. 2005, 115, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, G.; Elkamel, A.; Lohi, A. Enhancing CO2 Conversion to Methanol Using Dynamic Optimization, Applied on Shell Temperature and Inlet Hydrogen during 4 Years Operation of Methanol Plant. Energy Sources 2007, 29, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, N.; Jahanmiri, A.; Moghtaderi, B.; Rahimpour, M.R. A comparison of homogeneous and heterogeneous dynamic models for industrial methanol reactors in the presence of catalyst deactivation. Chem. Eng. Process. 2005, 44, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckl, I.; Kovacs, Z.; Friedler, F.; Fan, L.T.; Liu, J. Algorithmic synthesis of Chemical Engineering and processing an optimal sepration network comprising separators of different classes. Chem. Eng. Process. 2007, 46, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPC. Shiraz petrochemical complex methanol reactor long sheet, 2002-2005.

- Graaf, G.H.; Stamhuis, E.J.; Beenackers, A.A.C.M. Kinetics of low-pressure methanol synthesis. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1988, 43, 3185–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graaf, G.H.; Scholtens, H.; Stamhuis, E.J.; M.Beenackers, A.A.C. Intra-particle diffusion limitations in low-pressure methanol synthesis. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1990, 45, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathwork. 2008. Available online: www.mathwork.com.

- Methanex Methanol Price Sheet. 2005. Available online: www.methanex.com/products/methanol price.html.

- Peters, M.; Timmerhaus, K. Plant Design and Economics for Chemical Engineers, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, U.S.A., 1991. [Google Scholar]

© 2009 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Elkamel, A.; Reza Zahedi, G.; Marton, C.; Lohi, A. Optimal Fixed Bed Reactor Network Configuration for the Efficient Recycling of CO2 into Methanol. Energies 2009, 2, 180-189. https://doi.org/10.3390/en20200180

Elkamel A, Reza Zahedi G, Marton C, Lohi A. Optimal Fixed Bed Reactor Network Configuration for the Efficient Recycling of CO2 into Methanol. Energies. 2009; 2(2):180-189. https://doi.org/10.3390/en20200180

Chicago/Turabian StyleElkamel, Ali, Gholam Reza Zahedi, Chris Marton, and Ali Lohi. 2009. "Optimal Fixed Bed Reactor Network Configuration for the Efficient Recycling of CO2 into Methanol" Energies 2, no. 2: 180-189. https://doi.org/10.3390/en20200180