Synthesis and In Vitro Characterization of Fe3+-Doped Layered Double Hydroxide Nanorings as a Potential Imageable Drug Delivery System

Abstract

:1. Introduction

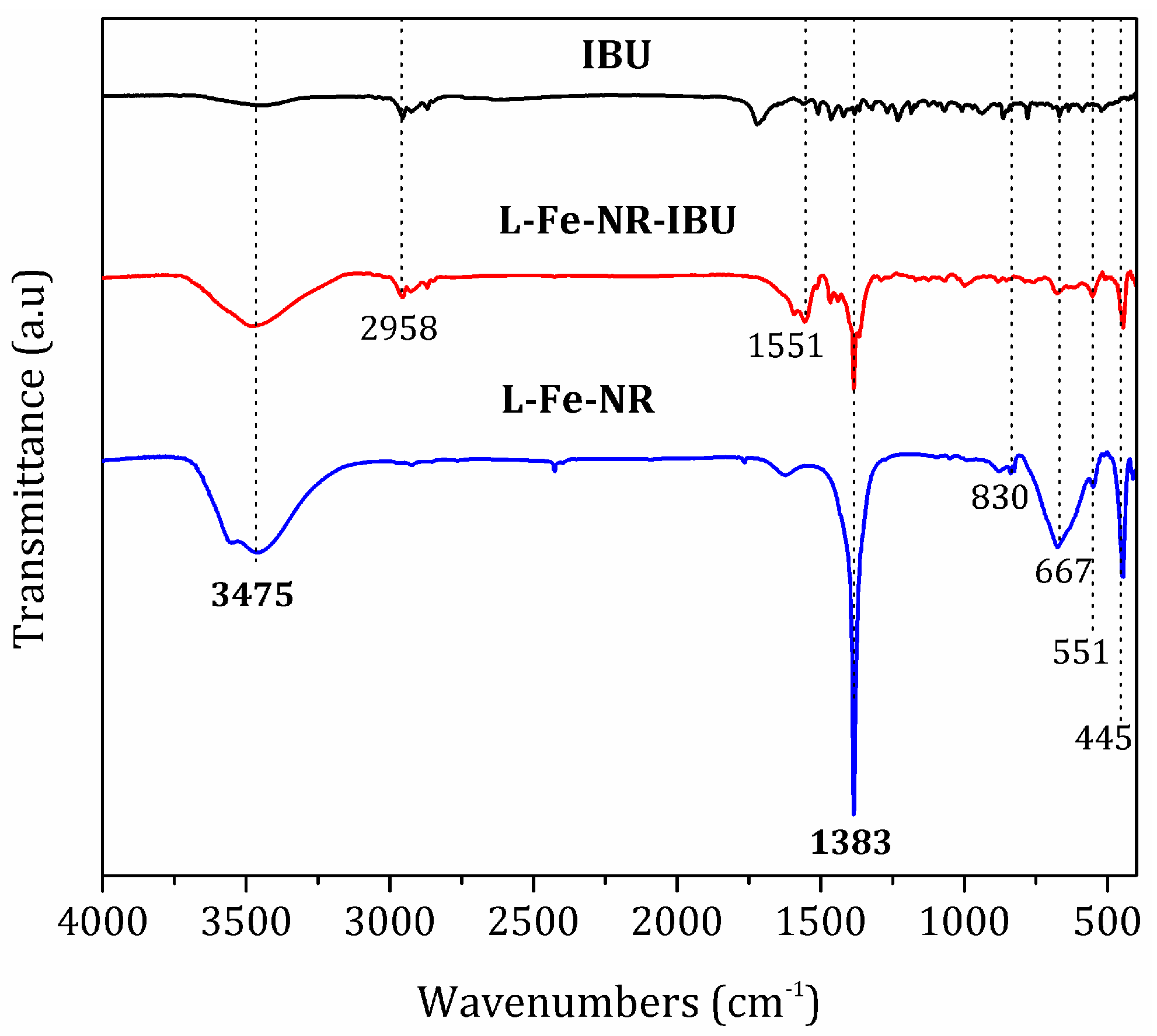

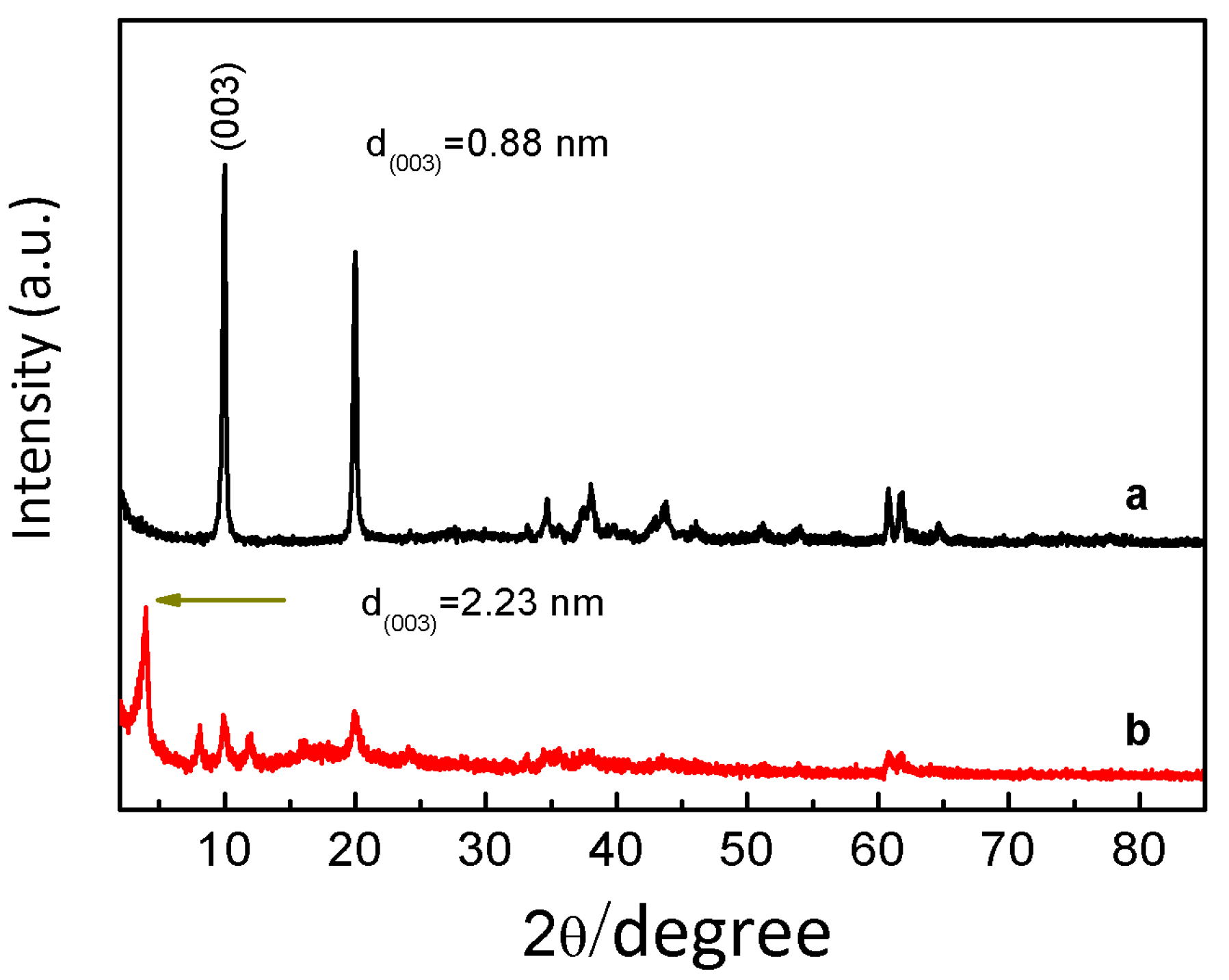

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

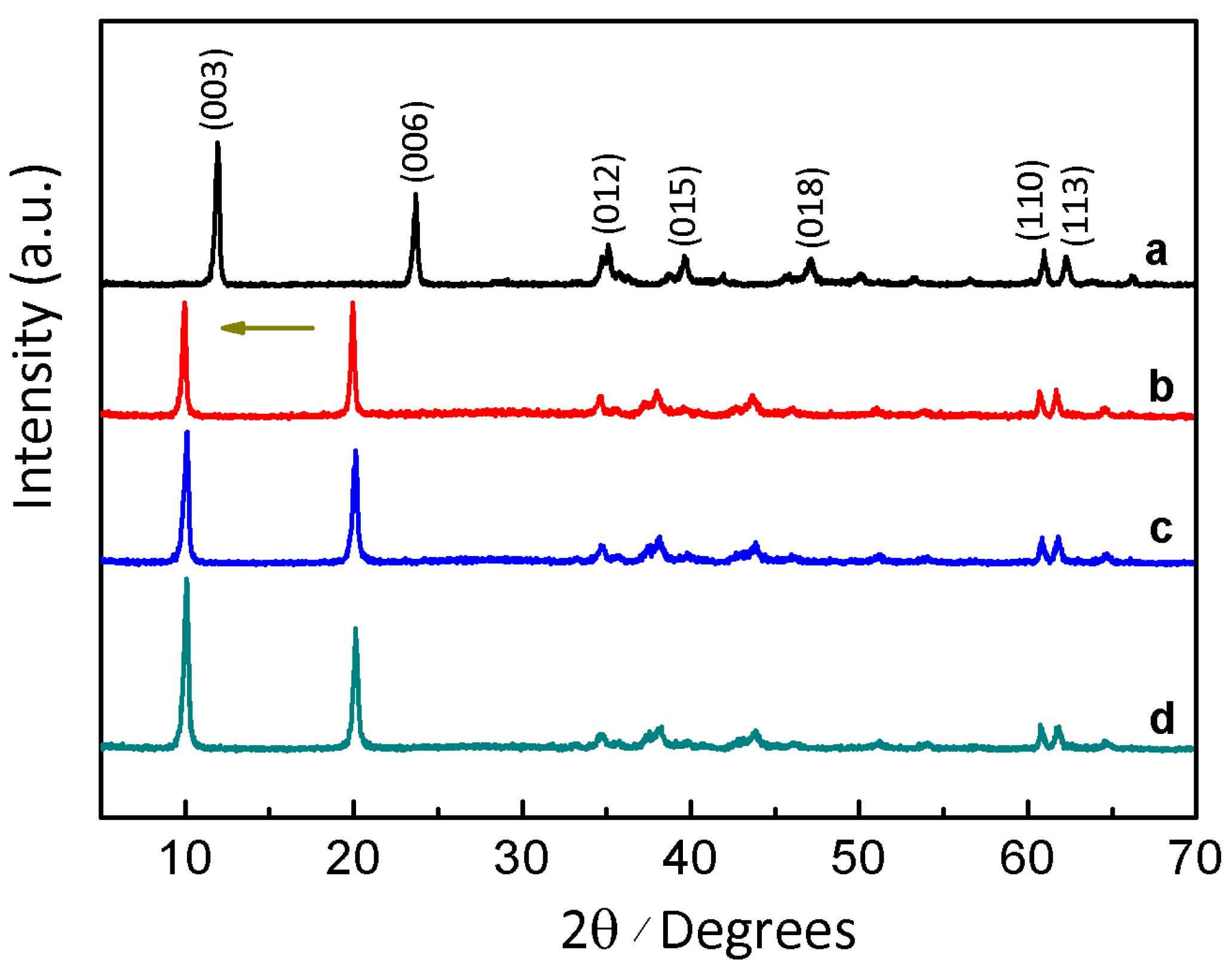

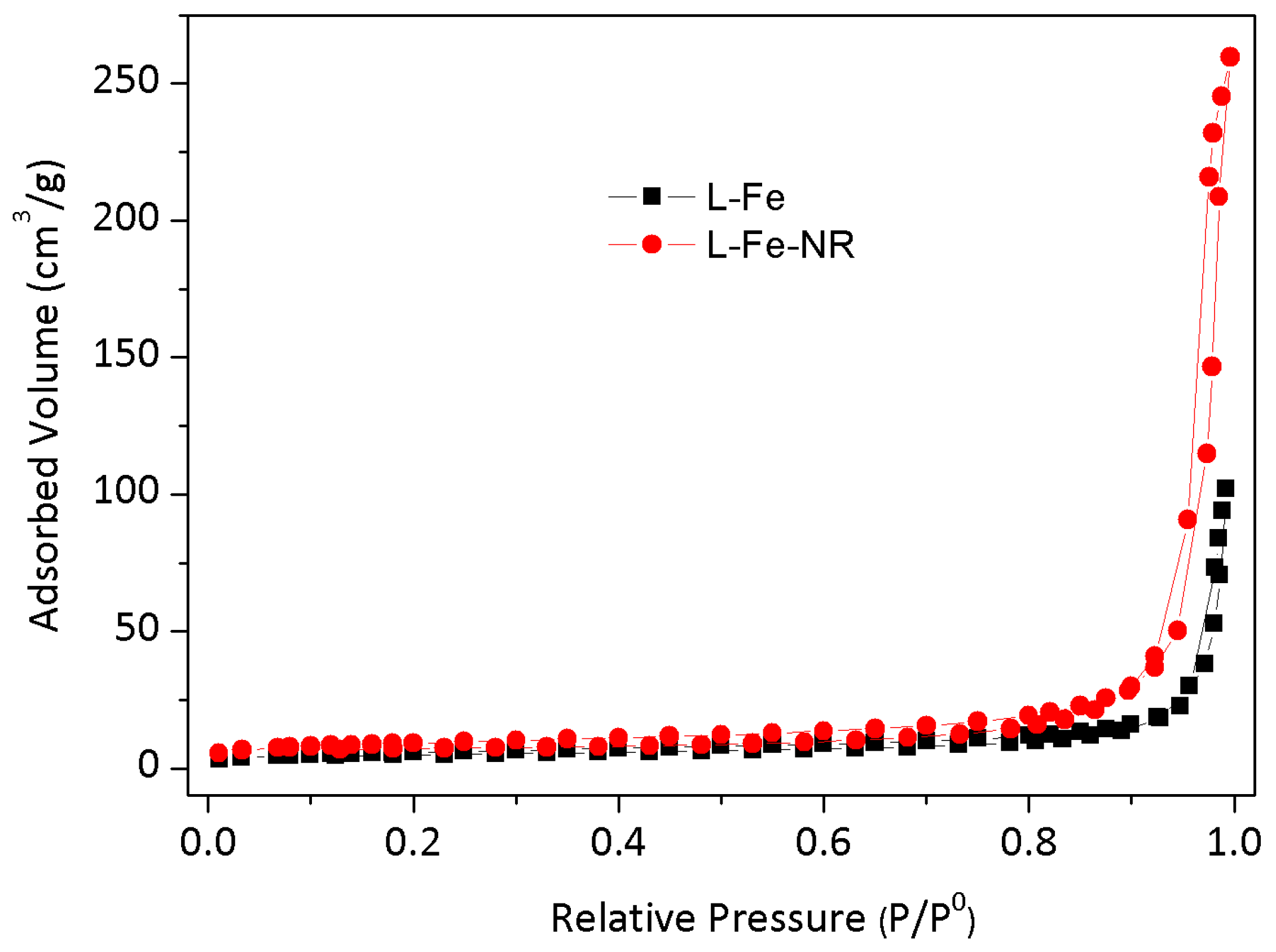

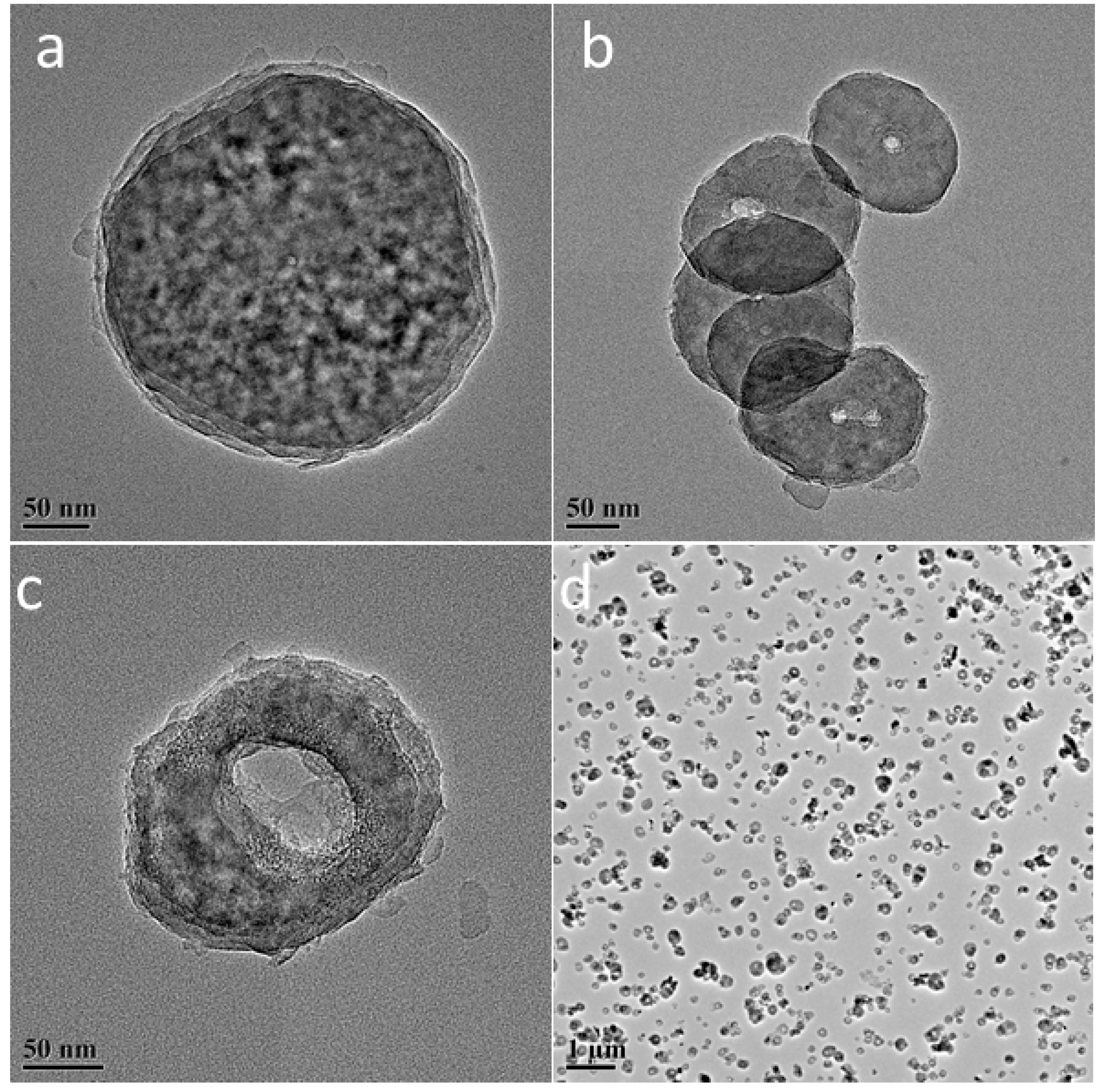

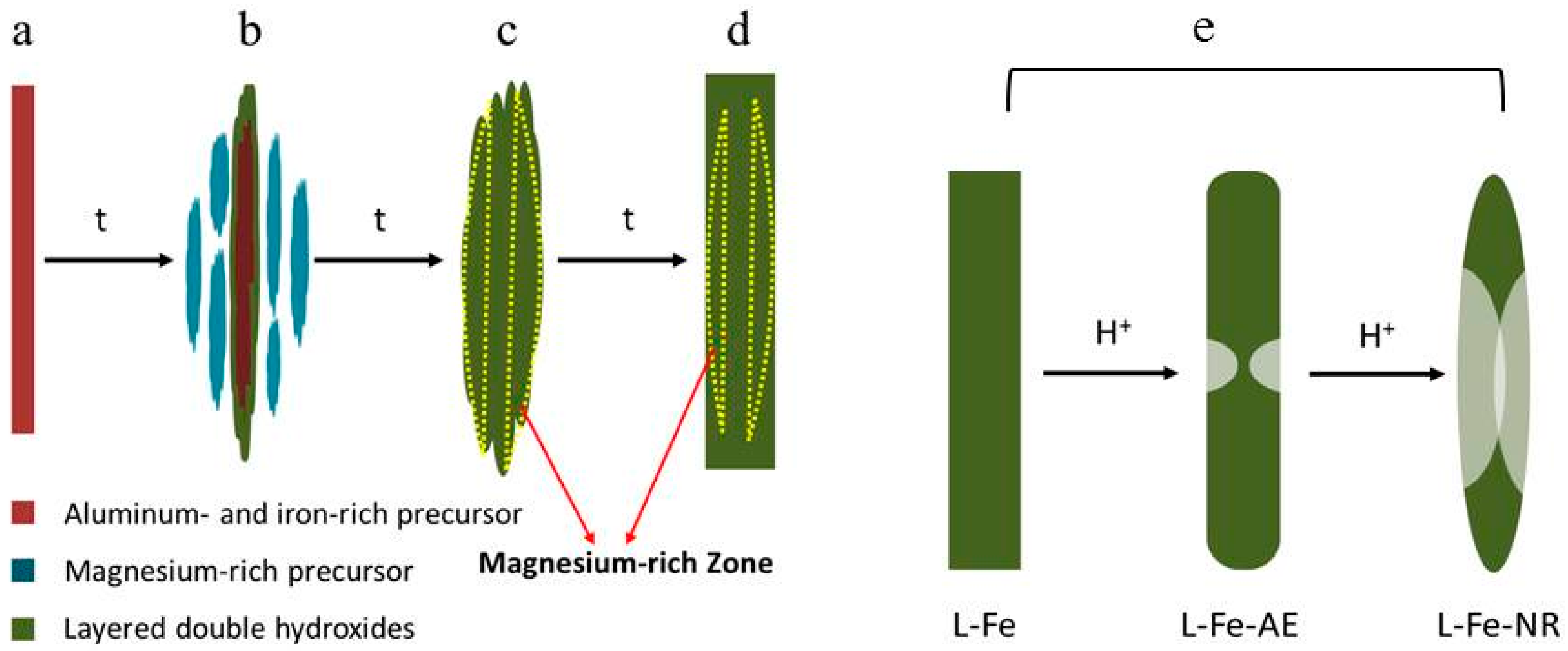

2.2. Preparation of L-Fe

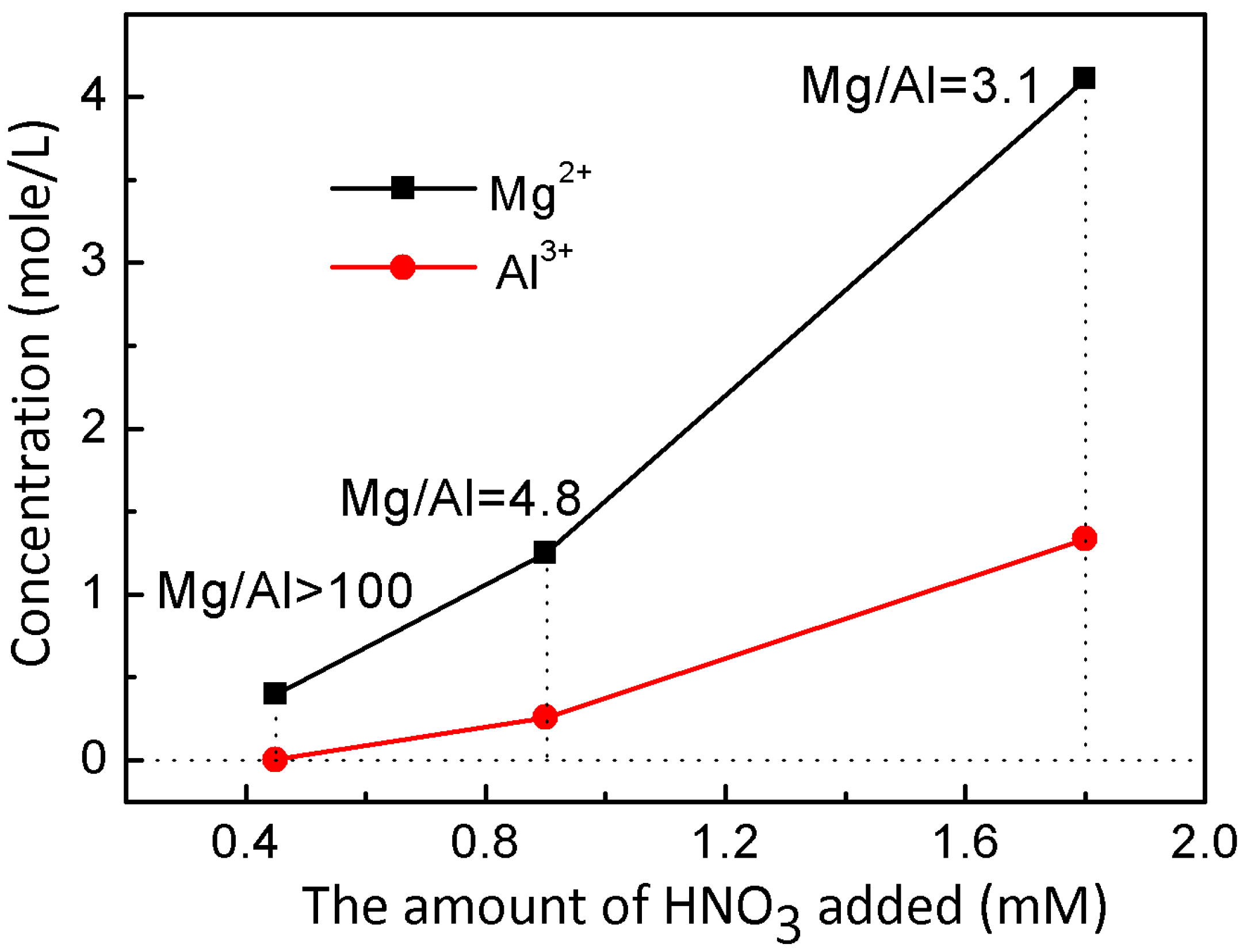

2.3. Preparation of L-Fe-NR

2.4. Characterization

2.5. Leaching of Fe3+ from the L-Fe-NR

2.6. MRI Performance Test

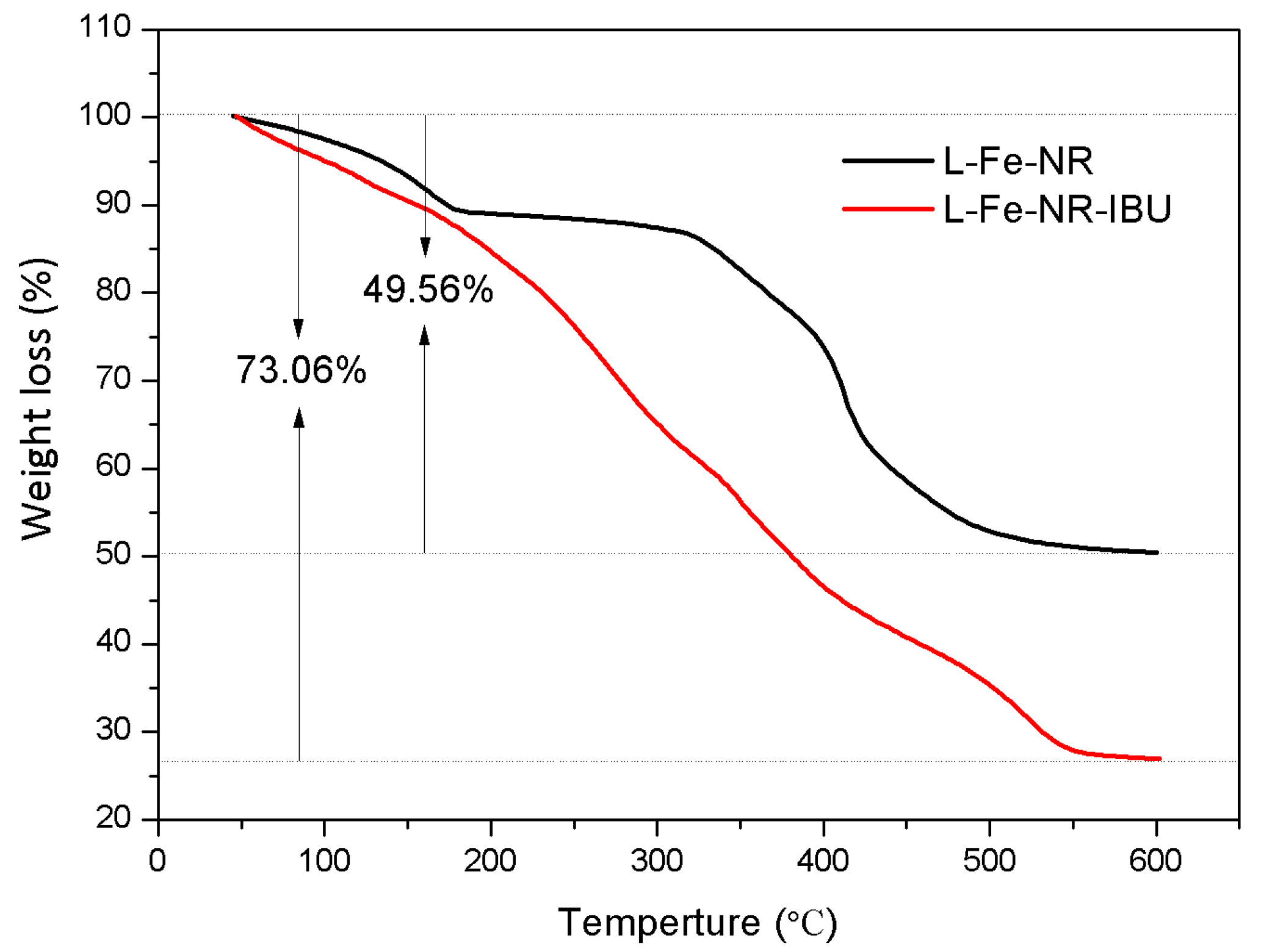

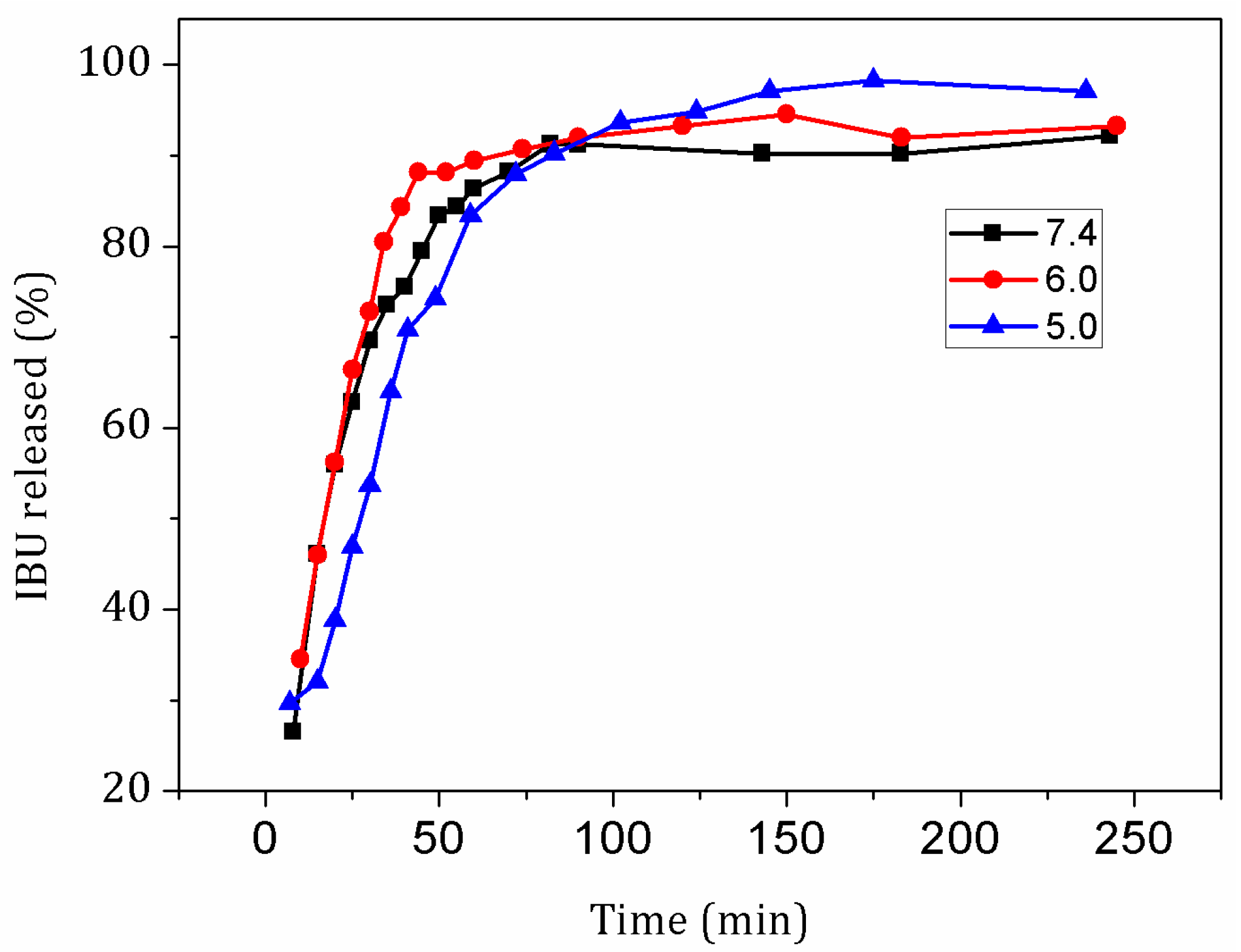

2.7. Drug Loading and Release

2.8. Cell Culture

2.9. Cytotoxicity Assay of L-Fe-NR

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Terreno, E.; Uggeri, F.; Aime, S. Image Guided Therapy: The Advent of Theranostic Agents. J. Control. Release 2012, 161, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, J.H.; Koo, H.; Sun, I.-C.; Yuk, S.H.; Choi, K.; Kim, K.; Kwon, I.C. Tumor-Targeting Multi-Functional Nanoparticles for Theragnosis: New Paradigm for Cancer Therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Bu, W.; Ni, D.; Zhang, S.; Li, Q.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yao, H.; Wang, Z.; Shi, J. Synthesis of Iron Nanometallic Glasses and Their Application in Cancer Therapy by a Localized Fenton Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 2101–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.; Qian, X.; Chen, Y.; Yu, L.; Lin, H.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, J. Metalloporphyrin-Encapsulated Biodegradable Nanosystems for Highly Efficient Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Guided Sonodynamic Cancer Therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, C.; Wilson, C.S.; Venuta, A.; Ferrari, M.; Arreto, C.D. Evolution of the Scientific Literature on Drug Delivery: A 1974–2015 Bibliometric Study. J. Control. Release 2017, 260, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.R.; Gambhir, S.S. Nanomaterials for in Vivo Imaging. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 901–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, T.; Li, F.; Baik, S.; Shao, W.; Ling, D.; Hyeon, T. Surface Design of Magnetic Nanoparticles for Stimuli-Responsive Cancer Imaging and Therapy. Biomaterials 2017, 136, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Bu, J.; Bu, W.; Zhang, S.; Pan, L.; Fan, W.; Chen, F.; Zhou, L.; Peng, W.; Zhao, K.; et al. Real-Time in Vivo Quantitative Monitoring of Drug Release by Dual-Mode Magnetic Resonance and Upconverted Luminescence Imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 126, 4639–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, R.; Mishra, S.; Maji, T.K.; Manna, K.; Kar, P.; Banerjee, S.; Dutta, S.; Sharma, S.K.; Lemmens, P.; Saha, K.D.; et al. A Novel Nanohybrid for Cancer Theranostics: Folate Sensitized Fe2O3 Nanoparticles for Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 3927–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Shin, W.S.; Sunwoo, K.; Kim, W.Y.; Koo, S.; Bhuniya, S.; Kim, J.S. Small Conjugate-Based Theranostic Agents: An Encouraging Approach for Cancer Therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6670–6683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, J.H.; Lee, S.; Son, S.; Kim, S.H.; Leary, J.F.; Choi, K.; Kwon, I.C. Theranostic Nanoparticles for Future Personalized Medicine. J. Control. Release 2014, 190, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, F.; Zhang, R.; Evans, D.G.; Duan, X. Preparation of Layered Double-Hydroxide Nanomaterials with a Uniform Crystallite Size Using a New Method Involving Separate Nucleation and Aging Steps. Chem. Mater. 2002, 14, 4286–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.P.; Lu, G.Q. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Layered Double Hydroxides (LDHs) from Mixed MgO and Al2O3: LDH Formation Mechanism. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, J.H.; Oh, J.M.; Park, M.; Sohn, K.M.; Kim, J.W. Inorganic-Biomolecular Hybrid Nanomaterials as a Genetic Molecular Code System. Adv. Mater. 2004, 16, 1181–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.J.; Shi, J.L.; Zhu, Y.; He, Q.J.; Xing, H.Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, F.; Chen, Y. Synthesis of a Multinanoparticle-Embedded Core/Mesoporous Silica Shell Structure as a Durable Heterogeneous Catalyst. Langmuir 2012, 28, 4920–4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.K.; Zhang, H.; Fan, T.; Chen, J.G.; Duan, X. Nearly Monodispersed Core-Shell Structural Fe3O4@DFUR-LDH Submicro Particles for Magnetically Controlled Drug Delivery and Release. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 908–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Thomas, A.C.; Xu, Z.P.; Campbell, J.H.; Lu, G.Q. In Vitro Sustained Release of LMWH from MgAl-Layered Double Hydroxide Nanohybrids. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 3715–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.F.; Ning, F.Y.; Zhao, J.W.; Wei, M.; Evans, D.G.; Duan, X. Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2@Layered Double Hydroxide Core-Shell Microspheres for Magnetic Separation of Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Harrison, R.; Zhou, J.Z.; Liu, T.T.; Yu, C.Z.; Lu, G.Q.; Qiao, S.Z.; Xu, Z.P. Synthesis of Nanorattles with Layered Double Hydroxide Core and Mesoporous Silica Shell as Delivery Vehicles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 21, 10641–10644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.F.; Yang, J.P.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Z.P.; Hao, N.; Wu, Z.X.; Lu, G.Q.; Zhao, D.Y. Synthesis of Well-Dispersed Layered Double Hydroxide Core@Ordered Mesoporous Silica Shell Nanostructure (LDH@MSiO2) and Its Application in Drug Delivery. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 4069–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.P.; Stevenson, G.S.; Lu, C.Q.; Lu, G.Q.M.; Bartlett, P.F.; Gray, P.P. Stable Suspension of Layered Double Hydroxide Nanoparticles in Aqueous Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.M.; Choi, S.J.; Lee, G.E.; Han, S.H.; Choy, J.H. Inorganic Drug-Delivery Nanovehicle Conjugated with Cancer-Cell-Specific Ligand. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 1617–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, J.D.; Li, Z.S.; Song, Y.C.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Z.H.; Zhang, M.L. Magnetic, Luminescent Eu-Doped Mg-Al Layered Double Hydroxide and Its Intercalation for Ibuprofen. Chem.-Eur. J. 2010, 16, 14404–14411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.X.; Hou, W.G.; Li, L.F.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.J. Synthesis and Characterization of 5-Fluorocytosine Intercalated Zn-Al Layered Double Hydroxide. J. Solid State Chem. 2008, 181, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.P.; Lu, J.; Wei, M.; Evans, D.G.; Duan, X. Sulforhodamine B Intercalated Layered Double Hydroxide Thin Film with Polarized Photoluminescence. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 1381–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Xing, H.; Zhang, S.; Ren, Q.; Pan, L.; Zhang, K.; Bu, W.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, L.; Peng, W.; et al. A Gd-Doped Mg-Al-LDH/Au Nanocomposite for Ct/Mr Bimodal Imagings and Simultaneous Drug Delivery. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 3390–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.; Hyeon, T. Designed Synthesis of Uniformly Sized Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Efficient Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2575–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, T.; Pouliot, P.; Avti, P.K.; Lesage, F.; Kakkar, A.K. Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Based Nanoprobes for Imaging and Theranostics. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 199, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.H.; Lee, N.; Kim, H.; An, K.; Park, Y.I.; Choi, Y.; Shin, K.; Lee, Y.; Kwon, S.G.; Na, H.B.; et al. Large-Scale Synthesis of Uniform and Extremely Small-Sized Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for High-Resolution T-1 Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12624–12631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.Y.; Ren, W.Z.; Zheng, J.J.; Cui, P.; Wu, A.G. Ultrasmall Water-Soluble Metal-Iron Oxide Nanoparticles as T-1-Weighted Contrast Agents for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 2631–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, H.B.; Hyeon, T. Nanostructured T1 Mri Contrast Agents. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 6267–6273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, H.B.; Lee, J.H.; An, K.; Park, Y.I.; Park, M.; Lee, I.S.; Nam, D.-H.; Kim, S.T.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, S.-W.; et al. Development of a T1 Contrast Agent for Magnetic Resonance Imaging Using Mno Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 119, 5493–5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.; Schnorr, J.; Pilgrimm, H.; Hamm, B.; Taupitz, M. Monomer-Coated Very Small Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Particles as Contrast Medium for Magnetic Resonance Imaging—Preclinical in Vivo Characterization. Investig. Radiol. 2002, 37, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfield, J.G.; Reilly, R.F. What Nephrologists Need to Know About Gadolinium. Nat. Clin. Pract. Nephr. 2007, 3, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtkot, J.; Snow, T.; Hiremagalur, B. Gadolinium and Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis: Association or Causation. Nephrology 2008, 13, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shellock, F.G.; Spinazzi, A. Mri Safety Update 2008: Part I, Mri Contrast Agents and Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2008, 191, 1129–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokouhimehr, M.; Soehnlen, E.S.; Hao, J.H.; Griswold, M.; Flask, C.; Fan, X.D.; Basilion, J.P.; Basu, S.; Huang, S.P.D. Dual Purpose Prussian Blue Nanoparticles for Cellular Imaging and Drug Delivery: A New Generation of T-1-Weighted Mri Contrast and Small Molecule Delivery Agents. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 5251–5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Su, Y.-D.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.-J.; Dong, L.; Gao, H.-L.; Lin, J.; Man, N.; et al. Mno Nanocrystals: A Platform for Integration of Mri and Genuine Autophagy Induction for Chemotherapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 1534–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulte, J.W.M.; Kraitchman, D.L. Iron Oxide Mr Contrast Agents for Molecular and Cellular Imaging. NMR Biomed. 2004, 17, 484–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tromsdorf, U.I.; Bruns, O.T.; Salmen, S.C.; Beisiegel, U.; Weller, H. A Highly Effective, Nontoxic T-1 Mr Contrast Agent Based on Ultrasmall Pegylated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Nano. Lett. 2009, 9, 4434–4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taboada, E.; Rodriguez, E.; Roig, A.; Oro, J.; Roch, A.; Muller, R.N. Relaxometric and Magnetic Characterization of Ultrasmall Iron Oxide Nanoparticles with High Magnetization. Evaluation as Potential T-1 Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agents for Molecular Imaging. Langmuir 2007, 23, 4583–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.Q.; Jia, Q.J.; Li, Y.L.; Gao, M.Y. Facile Synthesis of Ultrasmall Pegylated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Dual-Contrast T-1- and T-2-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Nanotechnology 2011, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.; Leporatti, S.; Donath, E.; Möhwald, H. Studies on the Drug Release Properties of Polysaccharide Multilayers Encapsulated Ibuprofen Microparticles. Langmuir 2001, 17, 5375–5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Lang, M.; Shi, J. Uniform Rattle-Type Hollow Magnetic Mesoporous Spheres as Drug Delivery Carriers and Their Sustained-Release Property. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 2780–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-F.; Shi, J.-L.; Li, Y.-S.; Chen, H.-R.; Shen, W.-H.; Dong, X.-P. Storage and Release of Ibuprofen Drug Molecules in Hollow Mesoporous Silica Spheres with Modified Pore Surface. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2005, 85, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorat, N.D.; Khot, V.M.; Salunkhe, A.B.; Ningthoujam, R.S.; Pawar, S.H. Functionalization of La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 Nanoparticles with Polymer: Studies on Enhanced Hyperthermia and Biocompatibility Properties for Biomedical Applications. Coll. Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 104, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.P.; Ma, R.Z.; Osada, M.; Iyi, N.; Ebina, Y.; Takada, K.; Sasaki, T. Synthesis, Anion Exchange, and Delamination of Co-Al Layered Double Hydroxide: Assembly of the Exfoliated Nanosheet/Polyanion Composite Films and Magneto-Optical Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 4872–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, A.K.; Sharma, P.; Sohn, H.-B.; Ghosh, S.; Das, R.K.; Hebard, A.F.; Zeng, H.; Baligand, C.; Walter, G.A.; Moudgil, B.M. Fe Doped Cdtes Magnetic Quantum Dots for Bioimaging. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 6312–6320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, M.; Jia, X.; Bai, J.; Ruan, Y.; Wang, C.; Sun, X.; Jiang, X. FeIII-Doped Two-Dimensional C3N4 Nanofusiform: A New O2-Evolving and Mitochondria-Targeting Photodynamic Agent for MRI and Enhanced Antitumor Therapy. Small 2016, 12, 5477–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuźnik, N.; Tomczyk, M.M.; Boncel, S.; Herman, A.P.; Koziol, K.K.K.; Kempka, M. Fe3+ Ions Anchored to Fe@O-Mwcnts as Double Impact T2 Mri Contrast Agents. Mater. Lett. 2014, 136, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ay, A.N.; Zümreoglu-Karan, B.; Temel, A.; Rives, V. Bioinorganic Magnetic Core–Shell Nanocomposites Carrying Antiarthritic Agents: Intercalation of Ibuprofen and Glucuronic Acid into Mg–Al–Layered Double Hydroxides Supported on Magnesium Ferrite. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 8871–8877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkhordari, S.; Yadollahi, M.; Namazi, H. pH Sensitive Nanocomposite Hydrogel Beads Based on Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Layered Double Hydroxide as Drug Delivery Systems. J. Polym. Res. 2014, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordijo, C.R.; Barbosa, C.A.S.; Ferreira, A.M.D.C.; Constantino, V.R.L.; Silva, D.D. Immobilization of Ibuprofen and Copper-Ibuprofen Drugs on Layered Double Hydroxides. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 94, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Arco, M.; Fernández, A.; Martín, C.; Rives, V. Solubility and Release of Fenbufen Intercalated in Mg, Al and Mg, Al, Fe Layered Double Hydroxides (LDH): The Effect of Eudragit® S 100 Covering. J. Solid State Chem. 2010, 183, 3002–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

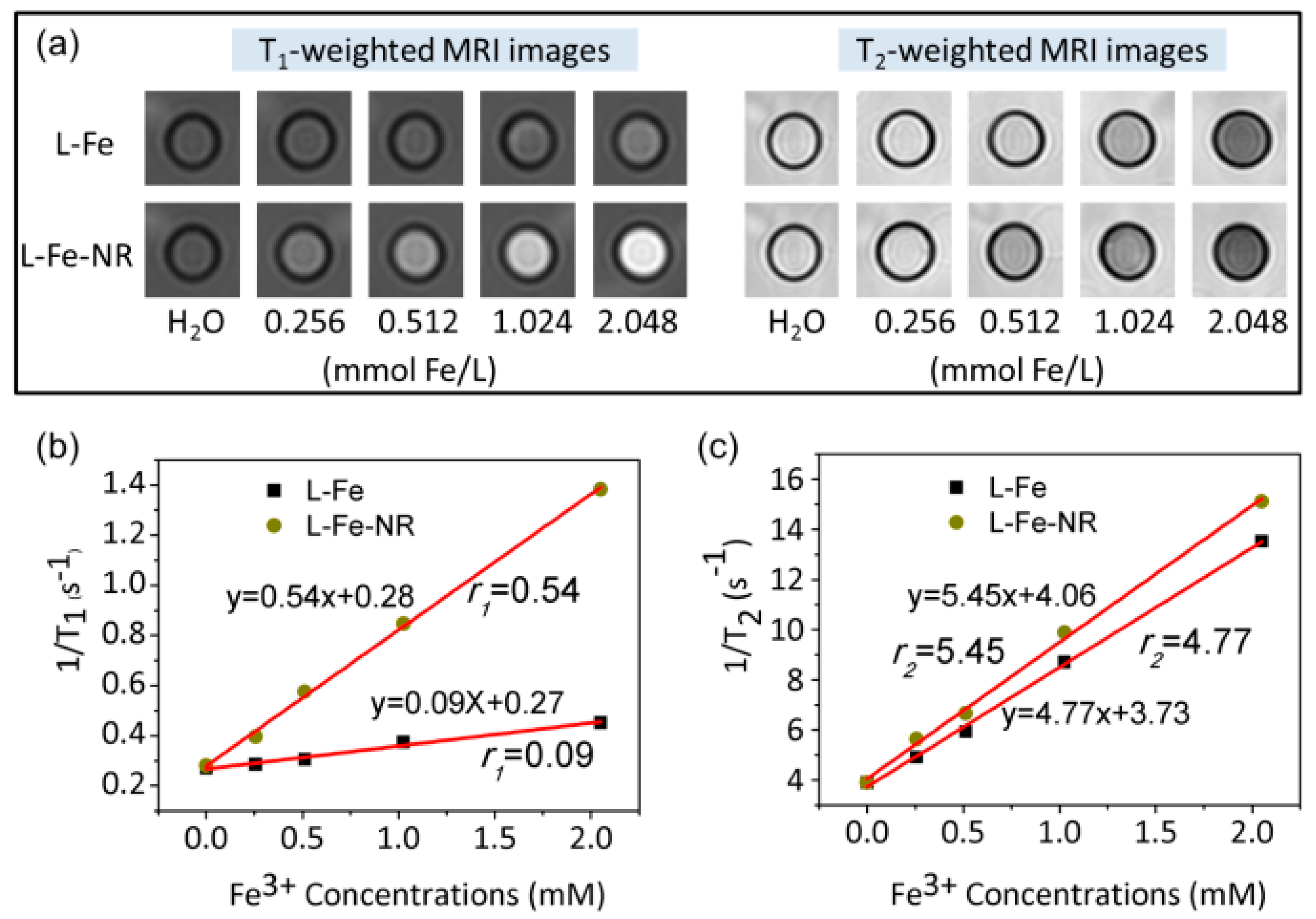

| Sample | L-Fe | L-Fe-AE-1 | L-Fe-AE-2 | L-Fe-NR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLS size (nm) | 266.1 | 169.4 | 152.0 | 94.5 |

| Zeta potential (mV) | 41.0 | 40.1 | 40.1 | 37.8 |

| SBET (m2/g) | 17.4 | 16.8 | 27.7 | 32.9 |

| Sample | Mg | Al | Fe | Al + Fe | Mg/(Al + Fe) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Fe | 66.0 | 32.7 | 1.3 | 34.0 | 1.94 |

| L-Fe-NR | 63.4 | 33.8 | 2.8 | 36.6 | 1.73 |

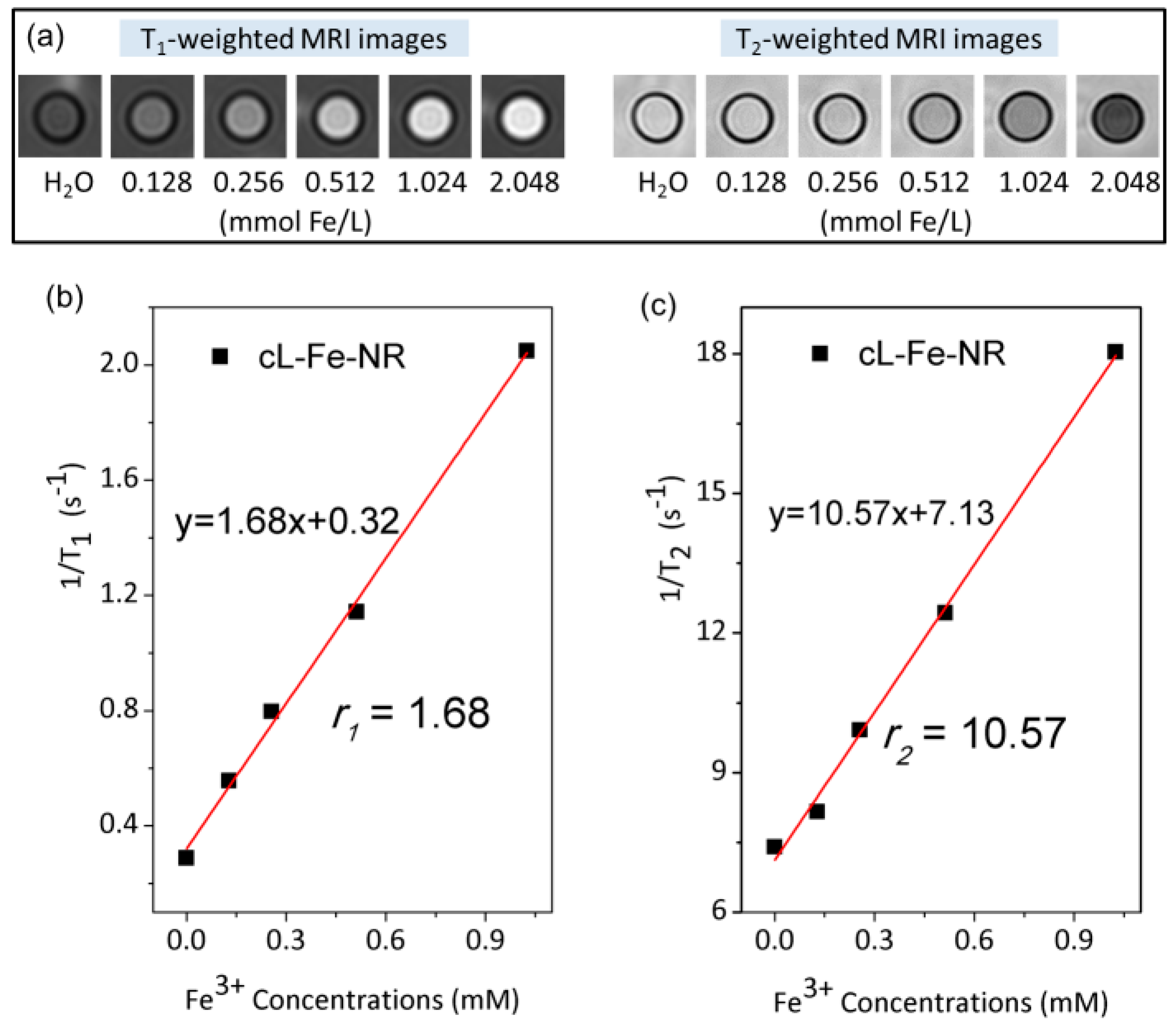

| Materials | r1 (mM−1·s−1) | r2 (mM−1·s−1) | r2/r1 | Magnetic Field Strength | Imaging Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Fe-NR | 0.54 | 4.77 | 8.83 | 3.0 T | T1 | This work |

| cL-Fe-NR | 1.68 | 10.57 | 6.29 | 3.0 T | T1 | This work |

| LDH-Gd(III) | 2.4 | - | - | 3.0 T | T1 | [26] |

| LDH-Gd(III)/Au | 6.6 | - | - | 3.0 T | T1 | [26] |

| CdTeS-Fe(III) | - | 3.60 | - | 4.7 T | T2 | [48] |

| C3N4-Fe(III) | 3.10 | 24.40 | 7.87 | 3.0 T | T1 | [49] |

| Fe@O-MWCNTs | 0.20 | 25.00 | 125 | 7.1 T | T2 | [50] |

| Fe(III)/Fe@O-MWCNTs | 0.21 | 35.00 | 167 | 7.1 T | T2 | [50] |

| MnO | 0.81 | - | - | 3.0 T | T1 | [38] |

| MnO@SiO2 | 1.34 | - | - | 3.0 T | T1 | [38] |

| MnO | 0.37 | 1.74 | 2.49 | 3.0 T | T1 | [32] |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Synthesis and In Vitro Characterization of Fe3+-Doped Layered Double Hydroxide Nanorings as a Potential Imageable Drug Delivery System. Materials 2017, 10, 1140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10101140

Wang L, Wang Y, Wang X. Synthesis and In Vitro Characterization of Fe3+-Doped Layered Double Hydroxide Nanorings as a Potential Imageable Drug Delivery System. Materials. 2017; 10(10):1140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10101140

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lijun, Yusen Wang, and Xiaoxia Wang. 2017. "Synthesis and In Vitro Characterization of Fe3+-Doped Layered Double Hydroxide Nanorings as a Potential Imageable Drug Delivery System" Materials 10, no. 10: 1140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10101140