Fabrication and Characterization of Porous MgAl2O4 Ceramics via a Novel Aqueous Gel-Casting Process

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Raw Materials and Preparation Process

2.2. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

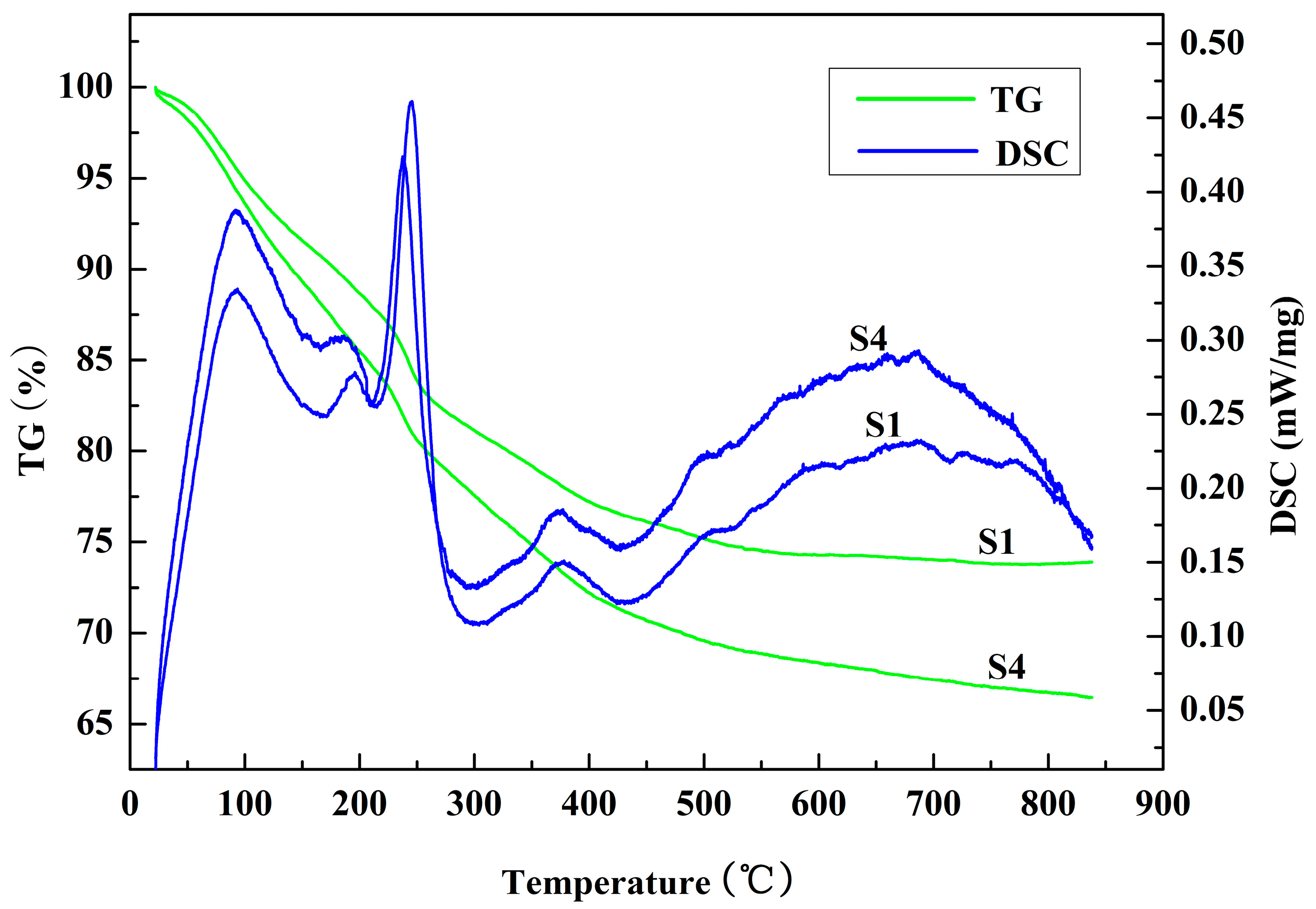

3.1. Hydration Properties

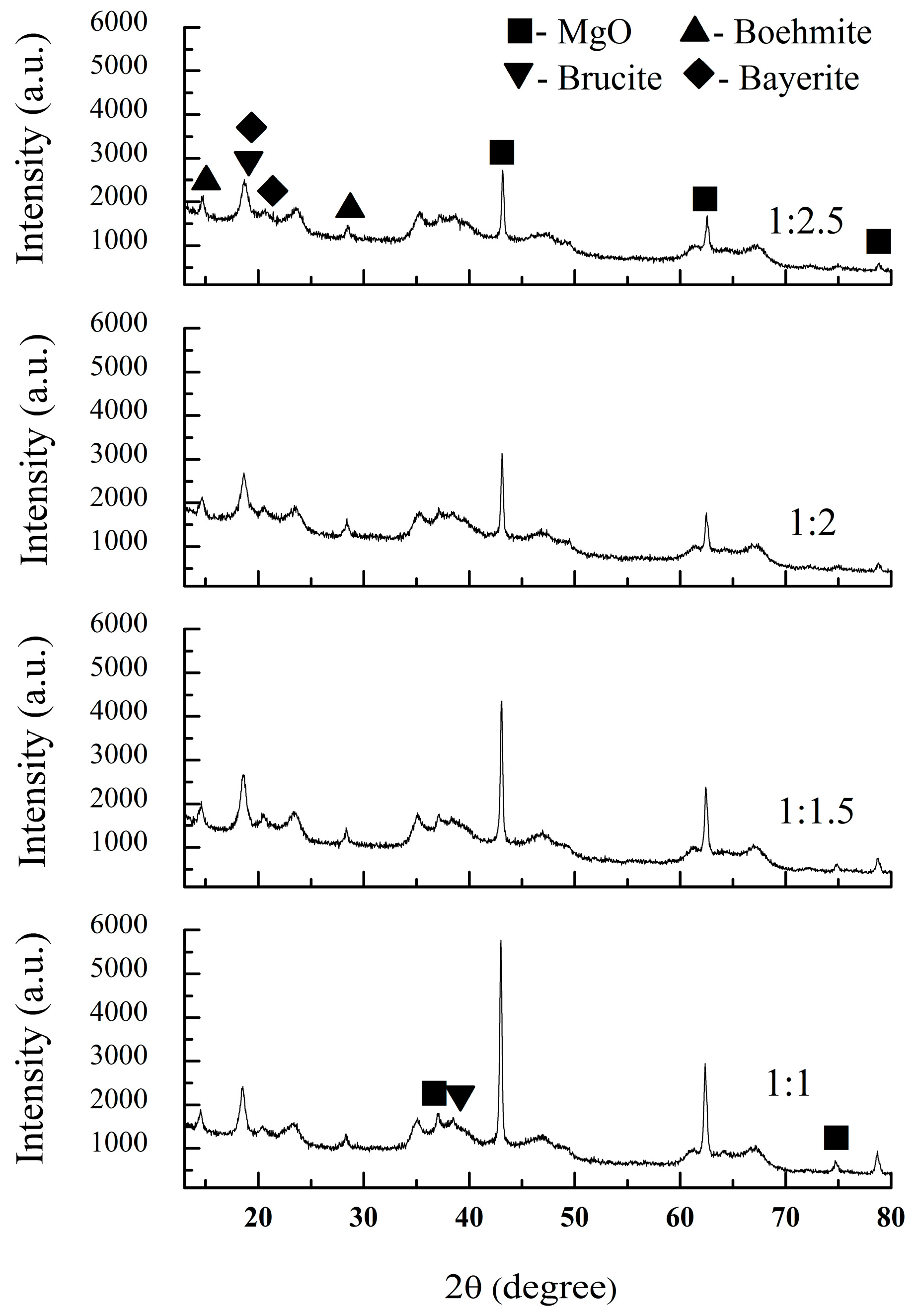

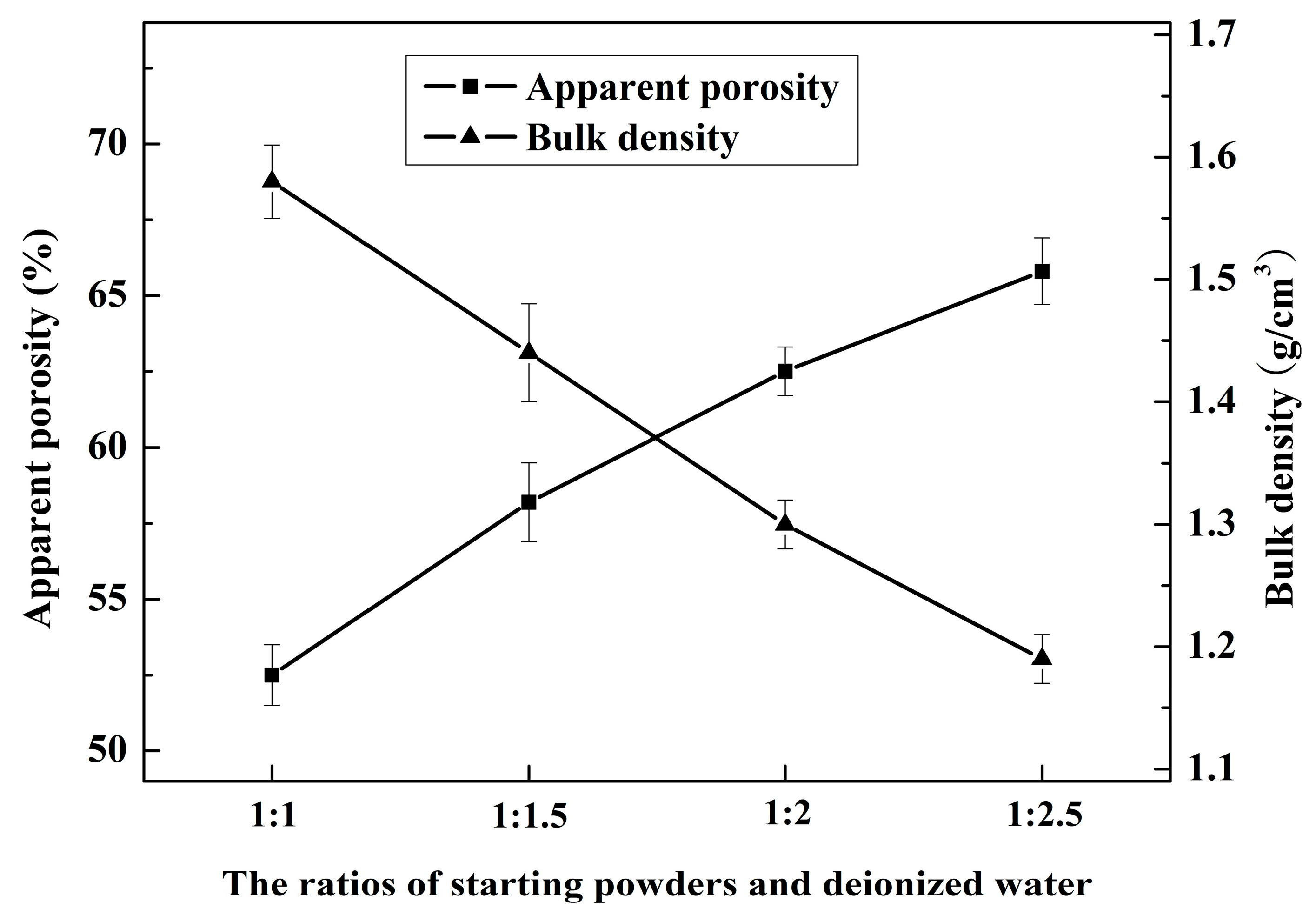

3.2. Phase Composition and Sintering Behaviors

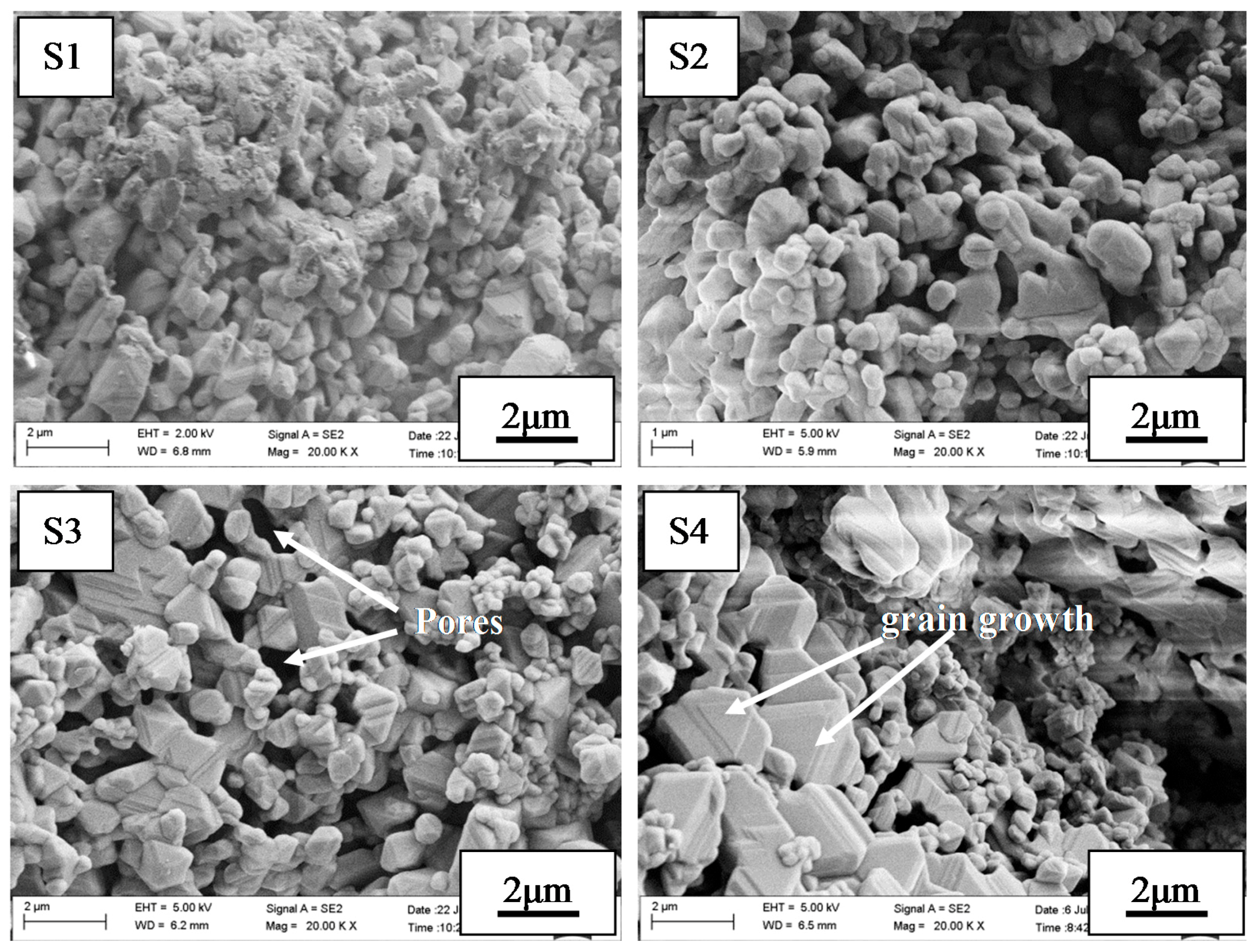

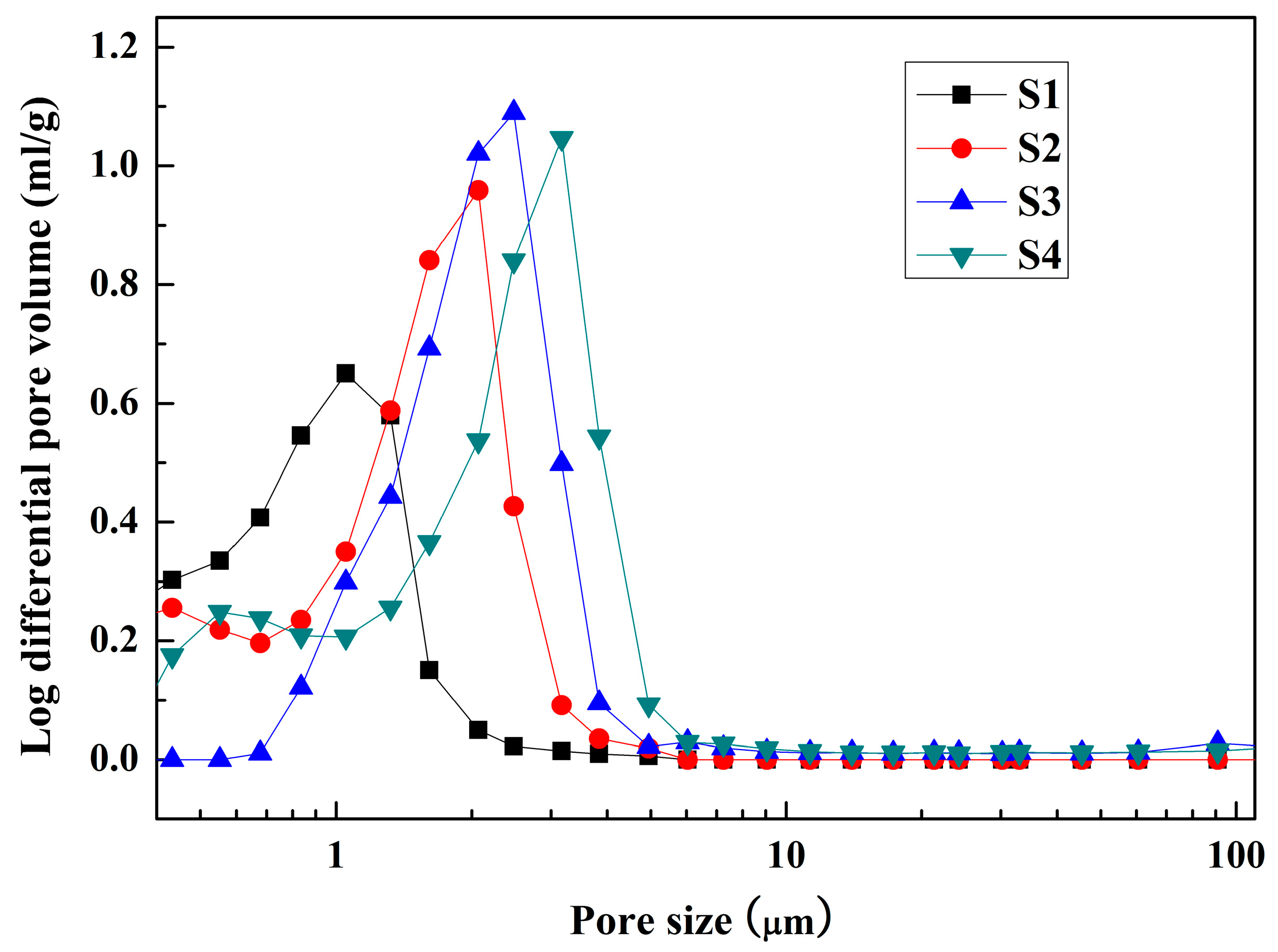

3.3. Microstructure and Pore Size Distribution

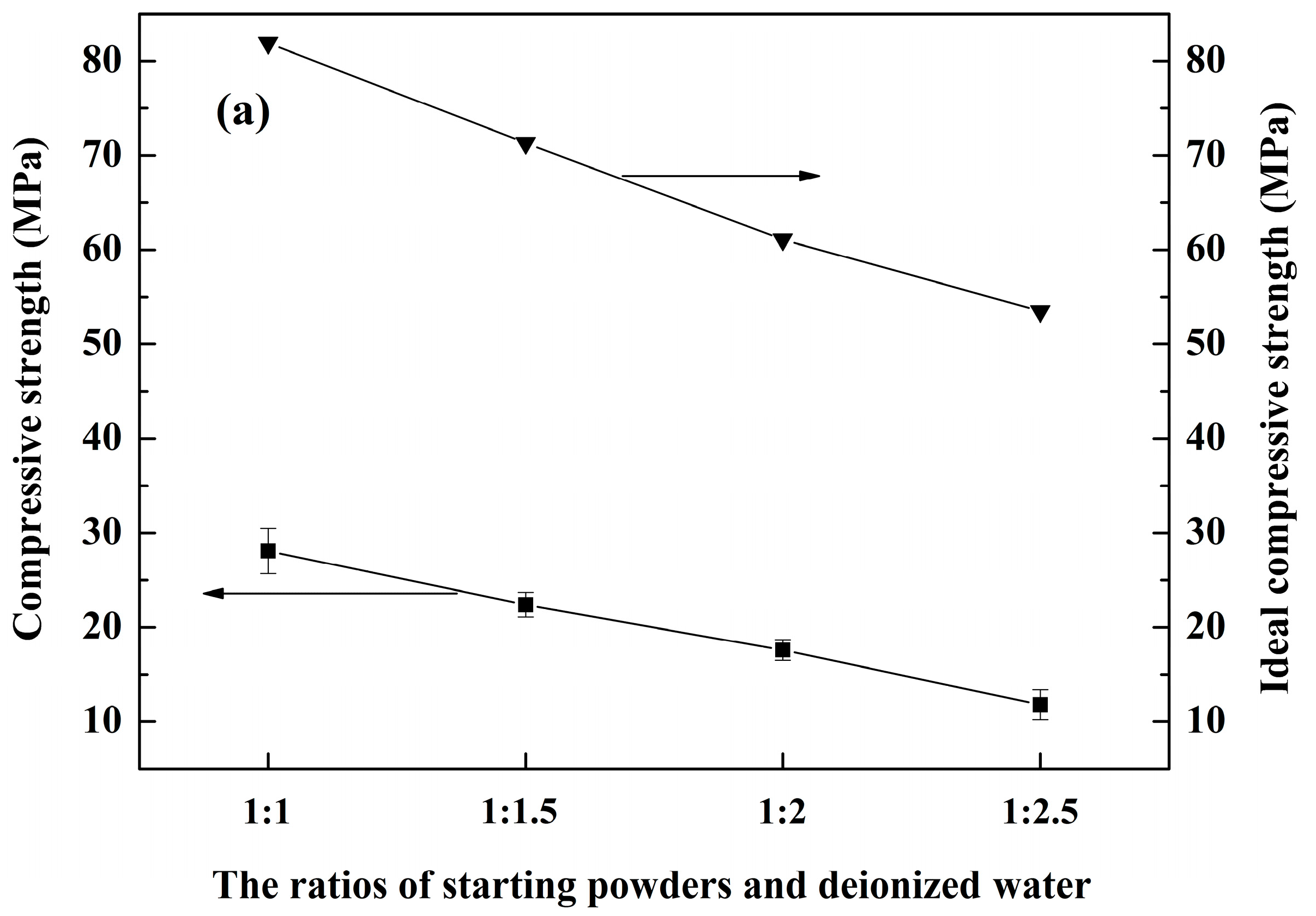

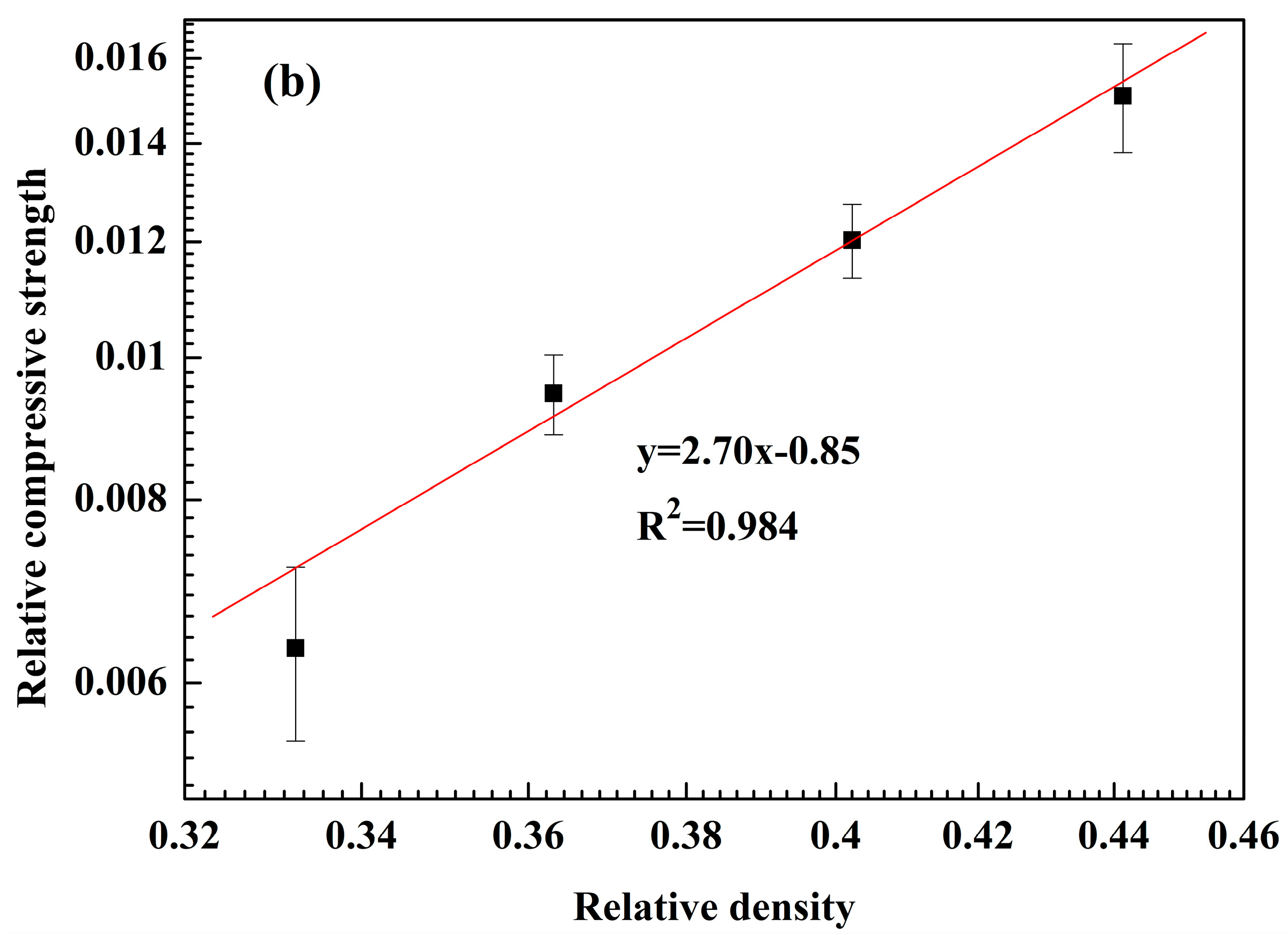

3.4. Mechanical Properties

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salomao, R.; Boas, M.O.C.V.; Pandolfelli, V.C. Porous alumina-spinel ceramics for high temperature applications. Ceram. Int. 2011, 37, 1393–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T.; Asoh, H.; Haraguchi, S.; Ono, S. Fabrication and characterization of single phase α-alumina membranes with tunable pore diameters. Materials 2015, 8, 1350–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesh, I. Fabrication of magnesium aluminate (MgAl2O4) spinel foams. Ceram. Int. 2011, 37, 2237–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Lin, X.L.; Chen, J.F.; Li, N.; Wei, Y.W.; Han, B.Q. Effect of TiO2 addition on microstructure and strength of porous spinel (MgAl2O4) ceramics prepared from magnesite and Al(OH)3. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 618, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ye, J.K.; He, G.; Liu, G.H.; Xie, Z.P.; Li, J.T. Preparation and characterization of porous MgAl2O4 spinel ceramic supports from bauxite and magnesite. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 2077–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, H.; Shokrollahi, H.; Alhaji, A. Optimizing the gel-casting parameters in synthesis of MgAl2O4 spinel. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 712, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, S.; Hashimoto, S.; Yase, S.; Daiko, Y.; Iwamoto, Y. Fabrication and thermal conductivity of highly porous alumina body from platelets with yeast fungi as a pore forming agent. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 13882–13887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, S.; Honda, S.; Hiramatsu, T.; Iwamoto, Y. Fabrication of porous spinel (MgAl2O4) from porous alumina using a template method. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 2077–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Chen, J.F.; Li, N.; Qiu, W.D.; Wei, Y.W.; Han, B.Q. Preparation and characterization of porous MgO-Al2O3 refractory aggregates using an in-situ decomposition pore-forming technique. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.H.; Wei, C.C.; Meng, F.T.; Liu, J.C.; Wang, P.; Du, Q.Y.; Tang, Z.X. Fabrication of porous Al2O3-MgAl2O4 ceramics using combustion-synthesized powders containing in situ produced pore-forming agents. Mater. Lett. 2011, 65, 1559–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, P.; Ortega, F.S.; Innocentini, M.D.M.; Pandolfelli, V.C. Properties of highly porous hydroxyapatite obtained by the gelcasting of foams. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2000, 83, 3021–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.P.; Li, Y.T.; Wang, C.A.; Tie, S.N. Fabrication of porous alumina-zirconia ceramics by gel-casting and infiltration methods. Mater. Des. 2014, 63, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Ma, B.Y.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, X.D.; Zhang, H.; Yu, J.K. Preparation and properties of mullite-bonded porous fibrous mullite ceramics by an epoxy resin gel-casting process. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 5478–5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Sun, L.C.; Wan, P.; Wang, J.Y. Preparation, microstructure and high temperature performances of porous γ-Y2Si2O7 by in situ foam-gelcasting using gelatin. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 14230–14238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhou, X.G.; Su, B. 3D interconnective porous alumina ceramics via direct protein foaming. Mater. Lett. 2009, 63, 830–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Feng, Y.B.; Yang, J.; Xu, S.; Qiu, T. Preparation of mesoporous silica ceramics with relatively high strength from industrial wastes by low-toxic aqueous gel-casting. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 35, 2163–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.G.; Wang, J.K.; Liu, J.H.; Zhang, H.J.; Li, F.L.; Duan, H.J.; Lu, L.L.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, W.G.; Zhang, S.W. Preparation and characterization of porous mullite ceramics via foam-gelcasting. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 9009–9017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, H.; Romero, A.R.; Ferroni, L.; Gardin, C.; Zavan, B.; Bernardo, E. Bioactive glass-ceramic scaffolds from novel ‘inorganic gel casting’ and sinter-crystallization. Materials 2017, 10, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, F.A.; Innocentini, M.D.M.; Miranda, M.F.S.; Valenzuela, F.A.O.; Pandolfelli, V.C. Drying behavior of hydratable alumina-bonded refractory castables. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2004, 24, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.P.; Brown, P.W. Mechanisms of reaction of hydratable aluminas. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1999, 82, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jia, Q.L.; Yan, S.; Zhang, S.M.; Liu, X.H. Microstructure and properties of hydratable alumina bonded bauxite andalusite based castables. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.F.; Ye, G.T.; Zhang, C.Y.; Zhu, L.L.; Song, X.J.; Ma, J. Chemical bonding and interlocking between hydratable alumina and microsilica after drying at 110 °C and firing at 800 °C. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 49, 3331–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomao, R.; Pandolfelli, V.C. The role of hydraulic binders on magnesia containing refractory castables: Calcium aluminate cement and hydratable alumina. Ceram. Int. 2009, 35, 3117–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lee, W.E. Carbon containing castables: Current status and future prospects. Br. Ceram. Trans. 2002, 101, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocentini, M.D.M.; Pardo, A.R.F.; Pandolfelli, V.C.; Menegazzo, B.A.; Bittencourt, L.R.M.; Rettore, R.P. Permeability of high-alumina refractory castables based on various hydraulic binders. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2002, 85, 1517–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.D.V.; Sousa, L.L.; Fernandes, L.; Cardoso, P.H.L.; Salomao, R. Al2O3-Al(OH)3-based castable porous structures. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 35, 1943–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.T.; Troczynski, T. Effect of magnesia on strength of hydratable alumina-bonded castable refractories. J. Mater. Sci. 2005, 40, 3921–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Troczynski, T. Hydration of hydratable alumina in the presence of various forms of MgO. Ceram. Int. 2006, 32, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, G.Q.; Liang, D.D. Preparation and properties of Al2O3-MgAl2O4 ceramic foams. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 3237–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilarska, A.A.; Klapiszewski, L.; Jesionowski, T. Recent development in the synthesis, modification and application of Mg(OH)2 and MgO: A review. Powder Technol. 2017, 319, 373–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.P.; Yan, Y.; Fan, X.Z.; Hu, Z.H.; Zhao, C.Y. Low-temperature synthesis of calcium-hexaluminate/magnesium-aluminum spinel composite ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 35, 2923–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersh, A.V.; Belyakov, A.V.; Mazalov, D.Y.; Solov’ev, S.A.; Sudnik, L.V.; Fedotov, A.V. Formation and sintering of boehmite and aluminum oxide nanopowders. Refract. Ind. Ceram. 2017, 57, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Zhang, J.; Liu, P.; Wang, S.W. Effect of polymorphism of Al2O3 on the sintering and microstructure of transparent MgAl2O4 ceramics. Opt. Mater. 2017, 71, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.J.; Ashby, M.F. Cellular Solids: Structure and Properties, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.G.; Wang, J.K.; Liu, J.H.; Zhang, H.J.; Han, L.; Zhang, S.W. Low cost foam-gelcasting preparation and characterization of porous magnesium aluminate spinel (MgAl2O4) ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 18215–18222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Starting Powders | Deionized Water | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ρ-Al2O3 | MgO | ||

| S1 | 37.0 | 13.0 | 50.0 |

| S2 | 29.6 | 10.4 | 60.0 |

| S3 | 24.6 | 8.7 | 66.7 |

| S4 | 21.2 | 7.4 | 71.4 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Z.; He, X.; Ma, B.; Zhu, Q.; Yu, J. Fabrication and Characterization of Porous MgAl2O4 Ceramics via a Novel Aqueous Gel-Casting Process. Materials 2017, 10, 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10121376

Yuan L, Liu Z, Liu Z, He X, Ma B, Zhu Q, Yu J. Fabrication and Characterization of Porous MgAl2O4 Ceramics via a Novel Aqueous Gel-Casting Process. Materials. 2017; 10(12):1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10121376

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Lei, Zongquan Liu, Zhenli Liu, Xiao He, Beiyue Ma, Qiang Zhu, and Jingkun Yu. 2017. "Fabrication and Characterization of Porous MgAl2O4 Ceramics via a Novel Aqueous Gel-Casting Process" Materials 10, no. 12: 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10121376