Toughening Mechanisms in Nanolayered MAX Phase Ceramics—A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Toughening in Nanolayered MAX Phases

2.1. Particle Toughening

2.2. Whisker- and Fiber-Reinforced Toughening

2.3. Transformation Toughening

2.4. Texture Toughening

3. Toughening Models for MAX Phases

3.1. SiC Particle-Reinforced Ti3SiC2 MAX Phase

3.2. SiC Fiber-Reinforced Ti3SiC2 MAX Phase

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- To apply these nanolayered MAX phases as higher performance and reliable structural components, a further tailoring of the microstructure should be done to enhance both strength and toughness. Through additional microstructure modification e.g., by grain size control, it is probable that the flexural strength or fracture toughness can be further enhanced.

- (2)

- For the fiber toughening MAX phases, more work should be done to optimize the interface between MAX phase and fibers, e.g., by selecting different fibers which could be phase equilibrium with MAX phase during the high-temperature processing or by new processing methods that can consolidate the composites with fast densification technology to reduce or avoid the reaction between the fibers and MAX phase matrix.

- (3)

- The modeling work presented here is just a first attempt to predict the improved toughness of the MAX phase-based composites by using 3D-FEM. However, more modeling parameters such as selection of proper reinforcements, the volume fraction of reinforcement as well as size and dimensions of the reinforcements etc. need to be further investigated and refined, which may provide valuable theoretical guidelines for material design, process development, and optimization.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Song, K.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, N.; Zhong, L.; Shang, Z.; Shen, L.; Wang, J. Evaluation of Fracture Toughness of Tantalum Carbide Ceramic Layer: A Vickers Indentation Method. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2016, 25, 3057–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, M.; Come, J.; Dyatkin, B.; Presser, V.; Taberna, P.-L.; Simon, P.; Barsoum, M.W.; Gogotsi, Y. MXene: A promising transition metal carbide anode for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 2012, 16, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.F.; Zhang, J.; Luo, D.W.; Gu, F.; Tang, D.Y.; Dong, Z.L.; Tan, G.E.B.; Que, W.X.; Zhang, T.S.; Li, S.; et al. Transparent ceramics: Processing, materials and applications. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2013, 41, 20–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, M.V. Toughening Mechanisms for Ceramics A2—SALAMA, K. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference On Fracture (ICF7), Houston, TX, USA, 20–24 March 1989; Ravi-Chandar, K., Taplin, D.M.R., Rao, P.R., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1989; pp. 3739–3786. [Google Scholar]

- Guazzato, M.; Albakry, M.; Ringer, S.P.; Swain, M.V. Strength, fracture toughness and microstructure of a selection of all-ceramic materials. Part II. Zirconia-based dental ceramics. Dent. Mater. 2004, 20, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abram, T.; Ion, S. Generation-IV nuclear power: A review of the state of the science. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4323–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yvon, P.; Carré, F. Structural materials challenges for advanced reactor systems. J. Nucl. Mater. 2009, 385, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammel, E.C.; Ighodaro, O.L.R.; Okoli, O.I. Processing and properties of advanced porous ceramics: An application based review. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 15351–15370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillig, W.B. Strength and Toughness of Ceramic Matrix Composites. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1987, 17, 341–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogotsi, G.A. Fracture toughness of ceramics and ceramic composites. Ceram. Int. 2003, 29, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallauri, D.; Atías Adrián, I.C.; Chrysanthou, A. TiC–TiB2 composites: A review of phase relationships, processing and properties. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 28, 1697–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rühle, M.; Evans, A.G. High toughness ceramics and ceramic composites. Prog. Mater Sci. 1989, 33, 85–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, R.O. The conflicts between strength and toughness. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Launey, M.E.; Ritchie, R.O. On the Fracture Toughness of Advanced Materials. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 2103–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, W.J.; Kendall, K.; Alford, N.M.; Button, T.W.; Birchall, J.D. A simple way to make tough ceramics. Nature 1990, 347, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsoum, M.W.; Kangutkar, P.; Wang, A.S.D. Matrix crack initiation in ceramic matrix composites Part I: Experiments and test results. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1992, 44, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsoum, M.W. The MN+1AXN phases: A new class of solids: Thermodynamically stable nanolaminates. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2000, 28, 201–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.M. Progress in research and development on MAX phases: A family of layered ternary compounds. Int. Mater. Rev. 2011, 56, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.B.; Bao, Y.W.; Zhou, Y.C. Current Status in Layered Ternary Carbide Ti3SiC2, a Review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2009, 25, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.H.; Zhou, Y.C. Layered Machinable and Electrically Conductive Ti2AlC and Ti3AlC2 Ceramics: A Review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2010, 26, 385–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsoum, M.W.; Radovic, M. Elastic and Mechanical Properties of the MAX Phases. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 2011, 41, 195–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, G.P.; Gauthier-Brunet, V.; Tromas, C.; Dubois, S. Synthesis, characterization, and intrinsic hardness of layered nanolaminate Ti3AlC2 and Ti3Al0. 8Sn0.2C2 solid solution. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2012, 95, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.T.; Meng, F.L.; Zhou, Y.C.; Bao, Y.W.; Chen, J.X. Effect of grain size, notch width, and testing temperature on the fracture toughness of Ti3Si(Al)C2 and Ti3AlC2 using the chevron-notched beam (CNB) method. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 28, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Pan, L.; Gu, W.; Qiu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, S. Microstructure and mechanical properties of in situ synthesized (TiB2 + TiC)/Ti3SiC2 composites. Ceram. Int. 2012, 38, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, M.; Bao, Y.; Zhou, Y. Failure-mode dependence of the strengthening effect in Ti3AlC2/10 vol % Al2O3 composite. Int. Mater. Res. 2006, 97, 1115–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.M.; Xu, Q.; Sloof, W.G.; Li, S.B.; van der Zwaag, S. Toughening of a ZrC particle-reinforced Ti3AIC2 composite. In Mechanical Properties and Processing of Ceramic Binary, Ternary, and Composite Systems: Ceramic Engineering and Science Proceedings, Daytona Beach, Florida USA, 27 January–1 February 2008; Salem, J., Hilma, G., Fahrenholtz, W., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhou, A.; Wang, L.; Li, S.; Wu, D.; Yan, C. In situ synthesis of cBN–Ti3AlC2 composites by high-pressure and high-temperature technology. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2012, 29, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benko, E.; Klimczyk, P.; Mackiewicz, S.; Barr, T.L.; Piskorska, E. cBN–Ti3SiC2 composites. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2004, 13, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendjemil, B.; Bougdira, J.; Zhang, F.; Burkel, E. Nano-ceramics Ti3SiC2 max phase reinforced single walled carbon nanotubes by spark plasma sintering. Int. Nanoelectron. Mater. 2017, 10, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konoplyuk, S.; Abe, T.; Uchimoto, T.; Takagi, T. Synthesis of Ti3SiC2/TiC composites from TiH2/SiC/TiC powders. Mater. Lett. 2005, 59, 2342–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, C.B.; Córdoba, J.M.; Obando, N.H.; Radovic, M.; Odén, M.; Hultman, L.; Barsoum, M.W. The Reactivity of Ti2AlC and Ti3SiC2 with SiC Fibers and Powders up to Temperatures of 1550 °C. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 94, 1737–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S. Improvement of mechanical properties of SiC(SCS-6) fibre-reinforced Ti3AlC2 matrix composites with Ti barrier layer. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 36, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Hu, C.; Gao, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Kagawa, Y. SiC(SCS-6) fiber-reinforced Ti3AlC2 matrix composites: Interfacial characterization and mechanical behavior. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 35, 1375–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, F.; Krenkel, W. Fabrication of fiber composites with a MAX phase matrix by reactive melt infiltration. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2011, 18, 202030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, C.B.; Córdoba, J.M.; Obando, N.; Sakulich, A.; Radovic, M.; Odén, M.; Hultman, L.; Barsoum, M.W. Phase Evaluation in Al2O3 Fiber-Reinforced Ti2AlC During Sintering in the 1300 °C–1500 °C Temperature Range. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 94, 3327–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik Parrikar, P.; Gao, H.; Radovic, M.; Shukla, A. Static and Dynamic Thermo-Mechanical Behavior of Ti2AlC MAX Phase and Fiber Reinforced Ti2AlC Composites. In Dynamic Behavior of Materials, Proceedings of the 2014 Annual Conference on Experimental and Applied Mechanics; Song, B., Casem, D., Kimberley, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, L.M. Preparation and Properties of Ternary Ti3AlC2 and its Composites from Ti–Al–C Powder Mixtures with Ceramic Particulates. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2007, 90, 1312–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.L.; Pan, W. Toughening of Ti3SiC2 with 3Y-TZP addition by spark plasma sintering. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 447, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Shi, S.-L. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Ti3SiC2/3Y-TZP composites by spark plasma sintering. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2007, 27, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Sakka, Y.; Grasso, S.; Nishimura, T.; Guo, S.; Tanaka, H. Shell-like nanolayered Nb4AlC3 ceramic with high strength and toughness. Scr. Mater. 2011, 64, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Sakka, Y.; Grasso, S.; Suzuki, T.; Tanaka, H. Tailoring Ti3SiC2 Ceramic via a Strong Magnetic Field Alignment Method Followed by Spark Plasma Sintering. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 94, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapauw, T.; Vanmeensel, K.; Lambrinou, K.; Vleugels, J. A new method to texture dense Mn+1AXn ceramics by spark plasma deformation. Scr. Mater. 2016, 111, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Mishra, M.; Hirano, H.; Suzuki, T.S.; Sakka, Y. Fabrication of textured Ti3SiC2 ceramic by slip casting in a strong magnetic field and pressureless sintering. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2014, 122, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Sakka, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Nishimura, T.; Grasso, S. Fabrication of Textured Nb4AlC3 Ceramic by Slip Casting in a Strong Magnetic Field and Spark Plasma Sintering. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 94, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunfeng, H.; Yoshio, S.; Toshiyuki, N.; Shuqi, G.; Salvatore, G.; Hidehiko, T. Physical and mechanical properties of highly textured polycrystalline Nb4AlC3 ceramic. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2011, 12, 044603. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.B.; Hu, C.F.; Sato, K.; Grasso, S.; Estili, M.; Guo, S.Q.; Morita, K.; Yoshida, H.; Nishimura, T.; Suzuki, T.S.; et al. Tailoring Ti3AlC2 ceramic with high anisotropic physical and mechanical properties. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 35, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.R.; Patel, V.; Chen, W.; Tolpygo, S.; Lukens, J.E. Quantum superposition of distinct macroscopic states. Nature 2000, 406, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blatter, G. Schrödinger’s cat is now fat. Nature 2000, 406, 25–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Huang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Li, Z. Application of the C-Me segregating theory in solid alloys to ceramics. Sci. China Ser. E 2007, 50, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.J. Application of the TFD Model and Yu’s Theory to Material Design. Prog. Nat. Sci. 1993, 3, 211–230. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Lin, L.Z.; Qing, Z.Y. Theoretical Research on Phase Transformations in Metastable β-Titanium Alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2009, 40, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.R. The empirical electron theory of solids and molecules. Chin. Sci. Bull. 1978, 23, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

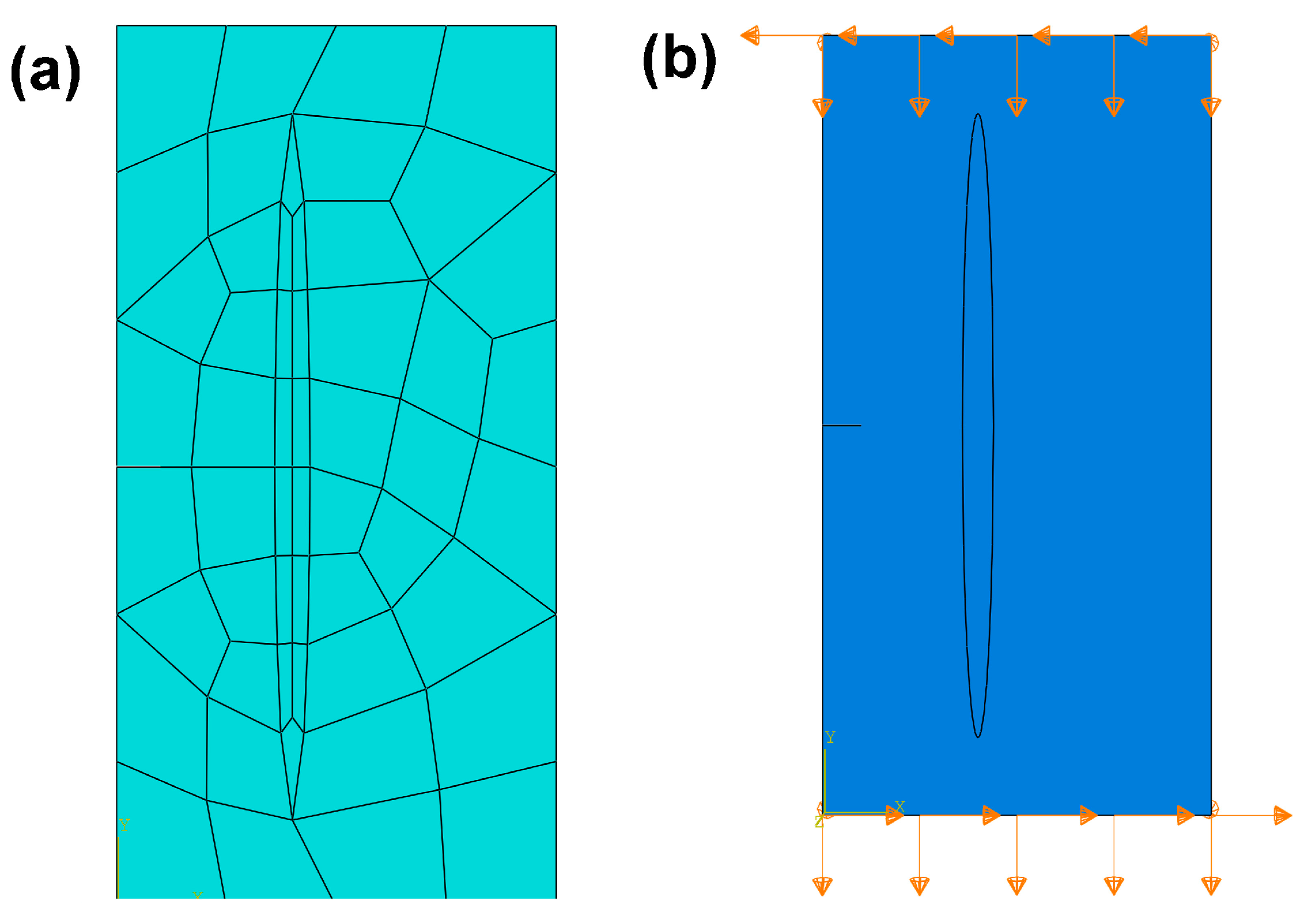

| Composites | Materials | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Dimension | Volume Fraction (%) | Half Crack Length (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiC-Ti3SiC2 system | Ti3SiC2 matrix | 333 | 0.2 | 0.05 × 0.1 × 0.002 mm3 | 93.2 | 0.005 |

| SiC particle | 440 | 0.14 | R = 0.006 mm | 6.8 | ||

| SiC-Ti3SiC2 system | Ti3SiC2 matrix | 333 | 0.2 | 0.05 × 0.1 × 0.002 mm3 | 95 | 0.005 |

| SiC-Fiber | 450 | 0.14 | a1 = 0.08 mm b1 = 0.004 mm | 5.0 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Bei, G. Toughening Mechanisms in Nanolayered MAX Phase Ceramics—A Review. Materials 2017, 10, 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10040366

Chen X, Bei G. Toughening Mechanisms in Nanolayered MAX Phase Ceramics—A Review. Materials. 2017; 10(4):366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10040366

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xinhua, and Guoping Bei. 2017. "Toughening Mechanisms in Nanolayered MAX Phase Ceramics—A Review" Materials 10, no. 4: 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10040366