Ternary CNTs@TiO2/CoO Nanotube Composites: Improved Anode Materials for High Performance Lithium Ion Batteries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Synthesis of TiO2 and TiO2/CoO Nanotubes

2.2. Synthesis of CNTs@TiO2/CoO NT Composite

2.3. Synthesis of Pure TiO2 and CNTs@TiO2 NTs

2.4. Material Characterization

2.5. Coin Cell Assembly and Electrochemical Testing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization

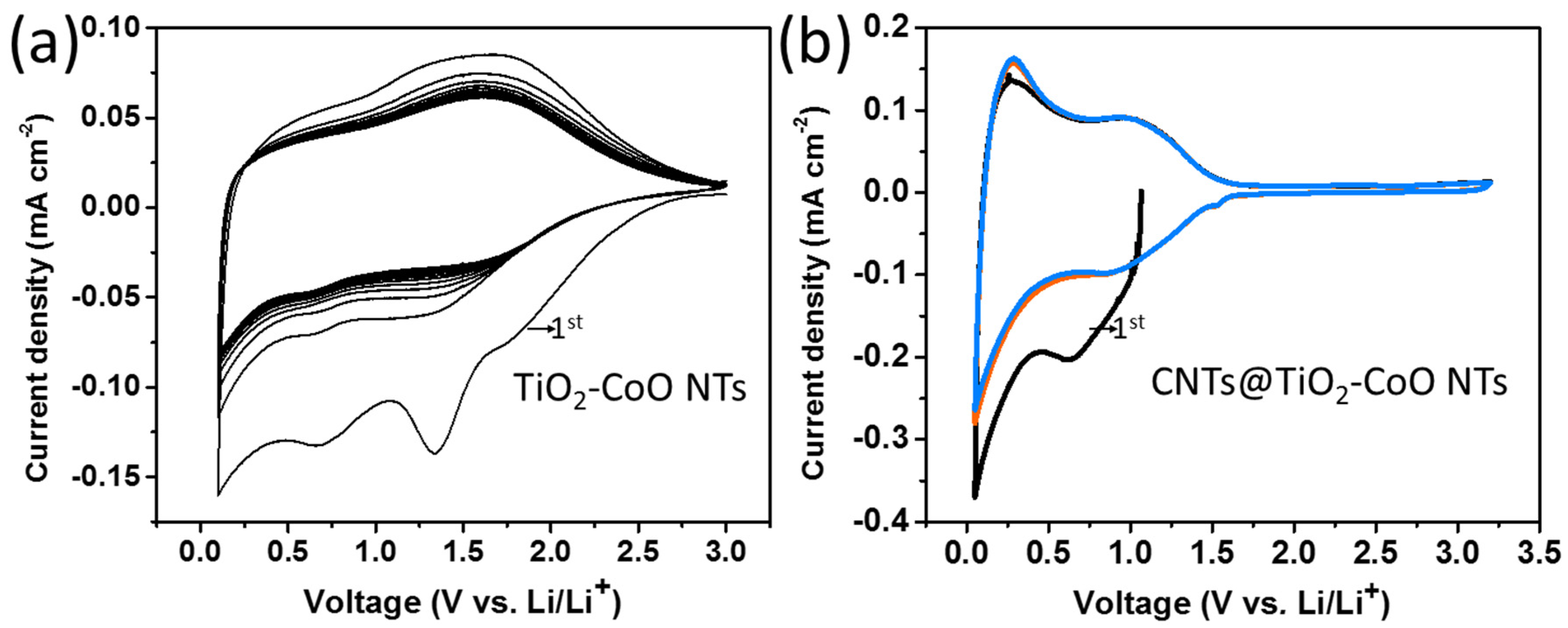

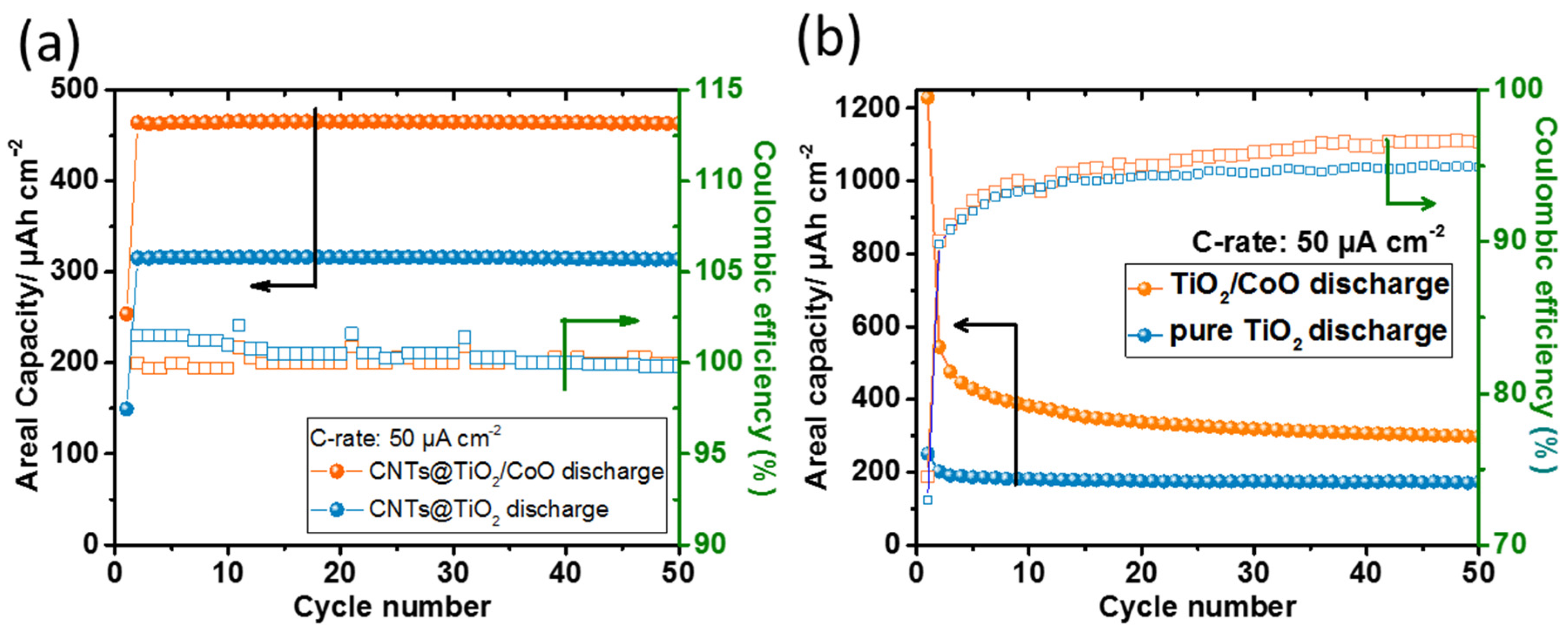

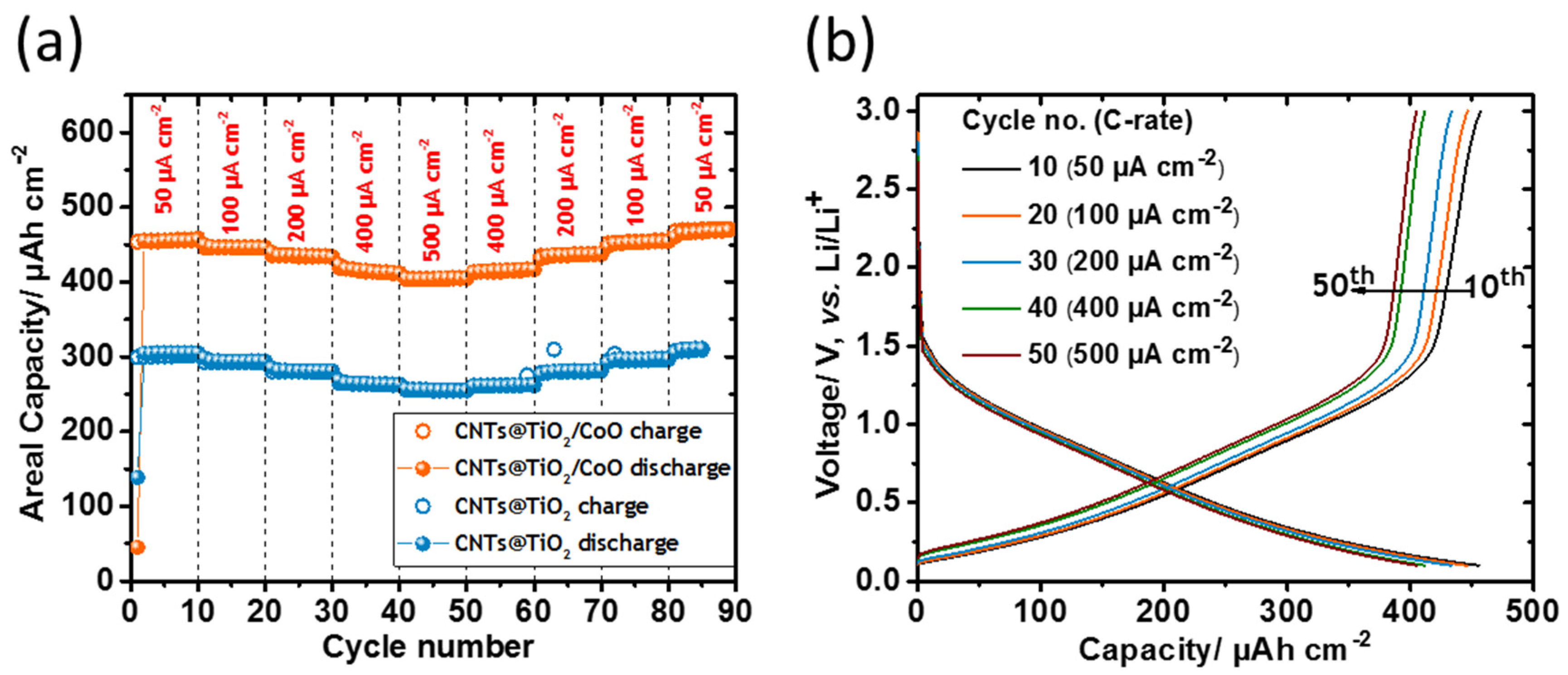

3.2. Electrochemical Testing

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, M.C.; Lee, Y.Y.; Xu, B.; Powers, K.; Meng, Y.S. TiO2 flakes as anode materials for Li-ion-batteries. J. Power Sources 2012, 207, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Ka, B.H.; Lee, C.; Park, M.; Oh, S.M. Preparation of nanotube TiO2-carbon composite and its anode performance in Lithium-ion batteries. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2009, 12, A28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Self, E.C.; Wycisk, R.; Pintauro, P.N. Electrospun titania-based fibers for high areal capacity Li-ion battery anodes. J. Power Sources 2015, 282, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mole, F.; Wang, J.; Clayton, D.A.; Xu, C.; Pan, S. Highly conductive nanostructured C-TiO2 electrodes with enhanced electrochemical stability and double layer charge storage capacitance. Langmuir 2012, 28, 10610–10619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, M.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Wu, S.; Yang, L.; Hu, S.; Xu, W.; Han, R.P.S.; Zou, R.; et al. Coaxial TiO2-carbon nanotube sponges as compressible anodes for Lithium-ion Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 7398–7405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, K.; Prakash, A.S.; Guruprakash, K.; Jayakumar, M. TiO2 coated carbon nanotubes for electrochemical energy storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 1757–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Feng, H.; Jiang, J.; Qian, D.; Li, J.; Peng, S.; Liu, Y. Anatase-TiO2/CNTs nanocomposite as a superior high-rate anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 603, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ran, R.; Tade, M.O.; Shao, Z. Self-assembled mesoporous TiO2/carbon nanotube composite with a three-dimensional conducting nanonetwork as a high-rate anode material for lithium-ion battery. J. Power Sources 2014, 254, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, N.T.H.; Ali, Z.; Kang, D.J. Mesoporous TiO2 spheres interconnected by multiwalled carbon nanotubes as an anode for high-performance lithium ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 3676–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, P.; Wu, Y.; Reddy, M.V.; Sreekumaran Nair, A.; Chowdari, B.V.R.; Ramakrishna, S. Long term cycling studies of electrospun TiO2 nanostructures and their composites with MWCNTs for rechargeable Li-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Le, Z.; Xu, Q.; Li, H.; Lu, Y. Mesoporous crystalline–amorphous oxide nanocomposite network for high-performance lithium storage. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 12056–12059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madian, M.; Giebeler, L.; Klose, M.; Jaumann, T.; Uhlemann, M.; Gebert, A.; Oswald, S.; Ismail, N.; Eychmüller, A.; Eckert, J. Self-organized TiO2/CoO nanotubes as potential anode materials for Lithium Ion batteries. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ummethala, R.; Fritzsche, M.; Jaumann, T.; Balach, J.; Oswald, S.; Nowak, R.; Sobczak, N.; Kaban, I.; Rümmeli, M.H.; Giebeler, L. Lightweight, free-standing 3D interconnected carbon nanotube foam as a flexible sulfur host for high performance lithium-sulfur battery cathodes. Energy Storage Mater. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ci, S.; Mao, S.; Cui, S.; Lu, G.; Yu, K.; Luo, S.; He, Z.; Chen, J. TiO2 nanoparticles-decorated carbon nanotubes for significantly improved bioelectricity generation in microbial fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2013, 234, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.W.; Zhou, L.K.; Li, H.X.; Wang, H.F.; Lang, J.P. One-pot growth of free-standing CNTs/TiO2 nanofiber membrane for enhanced photocatalysis. Mater. Lett. 2013, 95, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Cronin, S.B. Raman scattering of carbon nanotube bundles under axial strain and strain-induced debundling. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.C.; Jung, Y.M.; Noda, I.; Kim, S.B. A study of the mechanism of the electrochemical reaction of lithium with CoO by two-dimensional soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy (2D XAS), 2D Raman, and 2D Heterospectral XAS-Raman correlation analysis. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 5806–5811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, F.D. Raman spectroscopy of titania (TiO2) nanotubular water-splitting catalysts. J. Ark. Acad. Sci. 2011, 65, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Likodimos, V.; Stergiopoulos, T.; Falaras, P.; Kunze, J.; Schmuki, P. Phase composition, size, orientation, and antenna effects of self-assembled anodized titania nanotube arrays; a polarized micro-raman investigation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 12687–12696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüdiger, C.; Favaro, M.; Valero-Vidal, C.; Calvillo, L.; Bozzolo, N.; Jacomet, S.; Hejny, C.; Gregoratti, L.; Amati, M.; Agnoli, S.; et al. Fabrication of Ti substrate grain dependent C/TiO2 composites through carbothermal treatment of anodic TiO2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 9220–9231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgers, W.G.; Jacobs, F.M. Crystal structure of β-titanium. Z. Kristallogr. 1936, 94, 299–300. [Google Scholar]

- Skripov, A.V.; Buzlukov, A.L.; Soloninin, A.V.; Voronin, V.I.; Berger, I.F.; Udovic, T.J.; Huang, Q.; Rush, J.J. Hydrogen motion and site occupation in Ti2CoHx(Dx): NMR and neutron scattering studies. Physica B 2007, 392, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdett, J.K.; Hughbanks, T.; Miller, G.J.; Richardson, J.W.; Smith, J.V. Structural-electronic relationships in inorganic solids: Powder neutron diffraction studies of the rutile and anatase polymorphs of titanium dioxide at 15 and 295 K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 3639–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R.D.; Pask, J.A. Kinetics of the anatase-rutile transformation. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1965, 48, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madian, M.; Klose, M.; Jaumann, T.; Gebert, A.; Oswald, S.; Ismail, N.; Eychmüller, A.; Eckert, J.; Giebeler, L. Anodically fabricated TiO2–SnO2 nanotubes and their application in lithium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 2, 5542–5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Sun, X.; Zhou, C.; Cavanagh, A.S.; Sun, H.; Hu, T.; Wang, G.; Lian, J.; George, S.M. Amorphous ultrathin TiO2 atomic layer deposition films on carbon nanotubes as anodes for Lithium Ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, A974–A981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.T.; Liu, M.; Wang, D.W.; Sun, T.; Guan, D.S.; Li, F.; Zhou, J.; Sham, T.K.; Cheng, H.M. Comparison of the rate capability of nanostructured amorphous and anatase TiO2 for lithium insertion using anodic TiO2 nanotube arrays. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 225701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, R.T.; Niklasson, G.A.; Granqvist, C.G. Eliminating electrochromic degradation in amorphous TiO2 through Li-ion detrapping. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 5777–5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagemaker, M.; Borghols, W.J.H.; Mulder, F.M. Large Impact of particle size on insertion reactions. a case for anatase LixTiO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 4323–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubiak, P.; Pfanzelt, M.; Geserick, J.; Hörmann, U.; Hüsing, N.; Kaiser, U.; Wohlfahrt-Mehrens, M. Electrochemical evaluation of rutile TiO2 nanoparticles as negative electrode for Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2009, 194, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhu, H.; Pan, G.; Ye, S.; Lan, Y.; Wu, F.; Song, D. Preparation and electrochemical characterization of anatase nanorods for Lithium-inserting electrode material. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 2868–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Chen, J.S.; Lou, X.W.D. One-dimensional hierarchical structures composed of novel metal oxide nanosheets on a carbon nanotube backbone and their lithium-storage properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 4120–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.; Cai, C.; Wang, Y. Amorphous and crystalline TiO2 nanotube arrays for enhanced Li-ion intercalation properties. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2011, 11, 3641–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, H.; Yildirim, H.; Shevchenko, E.V.; Prakapenka, V.B.; Koo, B.; Slater, M.D.; Balasubramanian, M.; Sankaranarayanan, S.K.R.S.; Greeley, J.P.; Tepavcevic, S.; et al. Self-improving anode for Lithium-Ion batteries based on amorphous to cubic phase transition in TiO2 nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 3181–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, L.N.; Krause, R.W.; Kulkami, G.U.; Durbach, S.H. Synthesis and characterization of titania based binary metal oxide nanocomposite as potential environmental photocatalysts. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2011, 129, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, M.; Chen, G.; Deng, S.; Smirnov, S.; Luo, H.; Zou, G. Porous TiO2 conformal coating on carbon nanotubes as energy storage materials. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 169, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, C.; Yao, X.; Ma, R.; Wang, H.; Chen, P.; Zhang, K. Synthesis of carbon nanotube/mesoporous TiO2 coaxial nanocables with enhanced lithium ion battery performance. Carbon 2014, 75, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ci, S.; Mao, S.; Cui, S.; He, Z.; Chen, J. CNT@TiO2 nanohybrids for high-performance anode of lithium-ion batteries. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.D.; Wang, Y. Self-assembled echinus-like nanostructures of mesoporous CoO nanorod@CNT for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 6636–6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.C.; Hwang, I.S.; Seo, S.D.; Kim, D.W. Nanocomposite Li-ion battery anodes consisting of multiwalled carbon nanotubes that anchor CoO nanoparticles. Mater. Lett. 2013, 104, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Huang, K.; Fang, D.; Zhuang, S. Electrochemical properties of freestanding TiO2 nanotube membranes annealed in Ar for lithium anode material. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2012, 16, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Song, T.; Lee, E.K.; Devadoss, A.; Jeon, Y.; Ha, J.; Chung, Y.C.; Choi, Y.M.; Jung, Y.G.; Paik, U. Dominant factors governing the rate capability of a TiO2 nanotube anode for high power lithium ion batteries. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 8308–8315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Composition | Reversible Capacity/Current Density | Given Cycles | Preparation Method | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porous TiO2 nanoparticles/CNTs hybrid | 200 mAh·g−1/100 mA·g−1 | 100 | Sol-gel method | [36] |

| CNTs/mesoporous TiO2 coaxial nanocables | 183 mAh·g−1/168 mA·g−1 | 70 | Sol–gel and hydrothermal | [37] |

| Anatase /CNTs nanocomposite | 185 mAh·g−1/100 mA·g−1 | 100 | Hydrolysis | [7] |

| Mesoporous three-dimensional (3D) TiO2/carbon nanotube | 203 mAh·g−1/100 mA·g−1 | 100 | Solution-based synthesis process | [8] |

| Coaxial TiO2-Carbon Nanotube Sponges | 210 mAh·g−1/100 mA·g−1 | 100 | In situ hydrolysis | [5] |

| TiO2 nanoparticle-decorated carbon | 190 mAh·g−1/100 mA·g−1 | 120 | Thermal treatment | [38] |

| Mesoporous CoO nanorods@CNT | 703–746 mAh·g−1/3580 mA·g−1 | 200 | Hydrothermal technique | [39] |

| CoO nanoparticles/MWCNTs | 600–550 mAh·g−1/15 mA·g−1 | 100 | Electrophoretic deposition + CVD | [40] |

| CNTs@TiO2/CoO NT in this work | 410 mAh·g−1/45 mA·g−1 | 50 | Anodization followed by spray pyrolysis |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madian, M.; Ummethala, R.; Naga, A.O.A.E.; Ismail, N.; Rümmeli, M.H.; Eychmüller, A.; Giebeler, L. Ternary CNTs@TiO2/CoO Nanotube Composites: Improved Anode Materials for High Performance Lithium Ion Batteries. Materials 2017, 10, 678. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10060678

Madian M, Ummethala R, Naga AOAE, Ismail N, Rümmeli MH, Eychmüller A, Giebeler L. Ternary CNTs@TiO2/CoO Nanotube Composites: Improved Anode Materials for High Performance Lithium Ion Batteries. Materials. 2017; 10(6):678. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10060678

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadian, Mahmoud, Raghunandan Ummethala, Ahmed Osama Abo El Naga, Nahla Ismail, Mark Hermann Rümmeli, Alexander Eychmüller, and Lars Giebeler. 2017. "Ternary CNTs@TiO2/CoO Nanotube Composites: Improved Anode Materials for High Performance Lithium Ion Batteries" Materials 10, no. 6: 678. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10060678