Research on High Layer Thickness Fabricated of 316L by Selective Laser Melting

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experimental Equipment

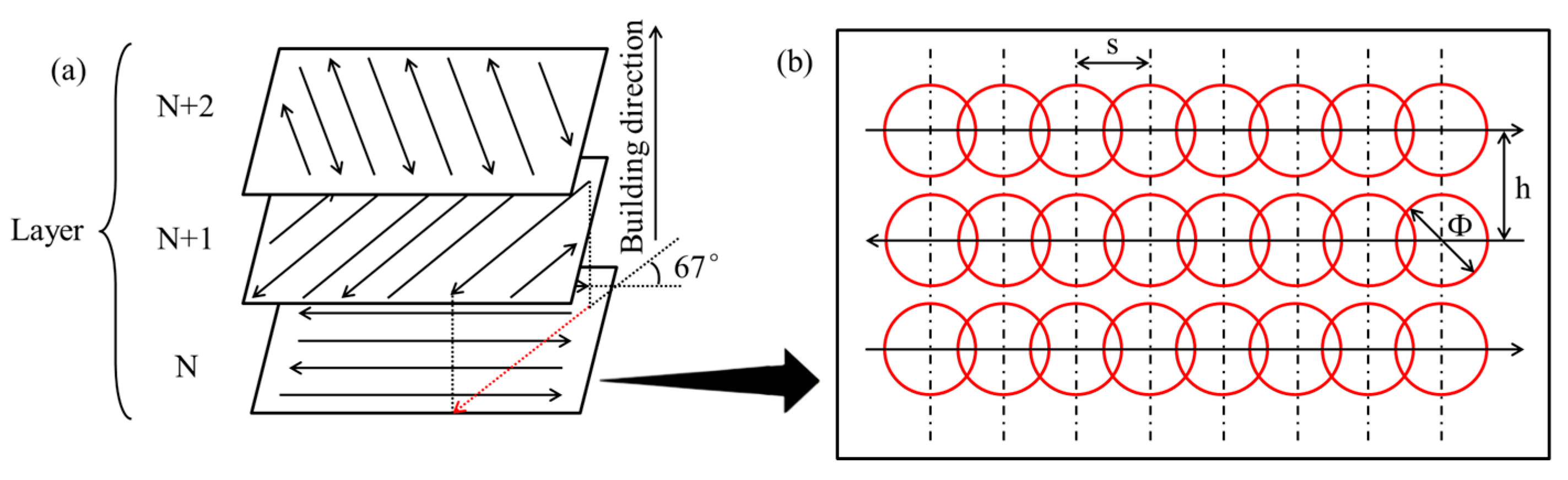

2.3. Experimental Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Single-Track Experiments

3.2. Multi-Layer Fabrications

3.2.1. Relative Density

3.2.2. Building Rate

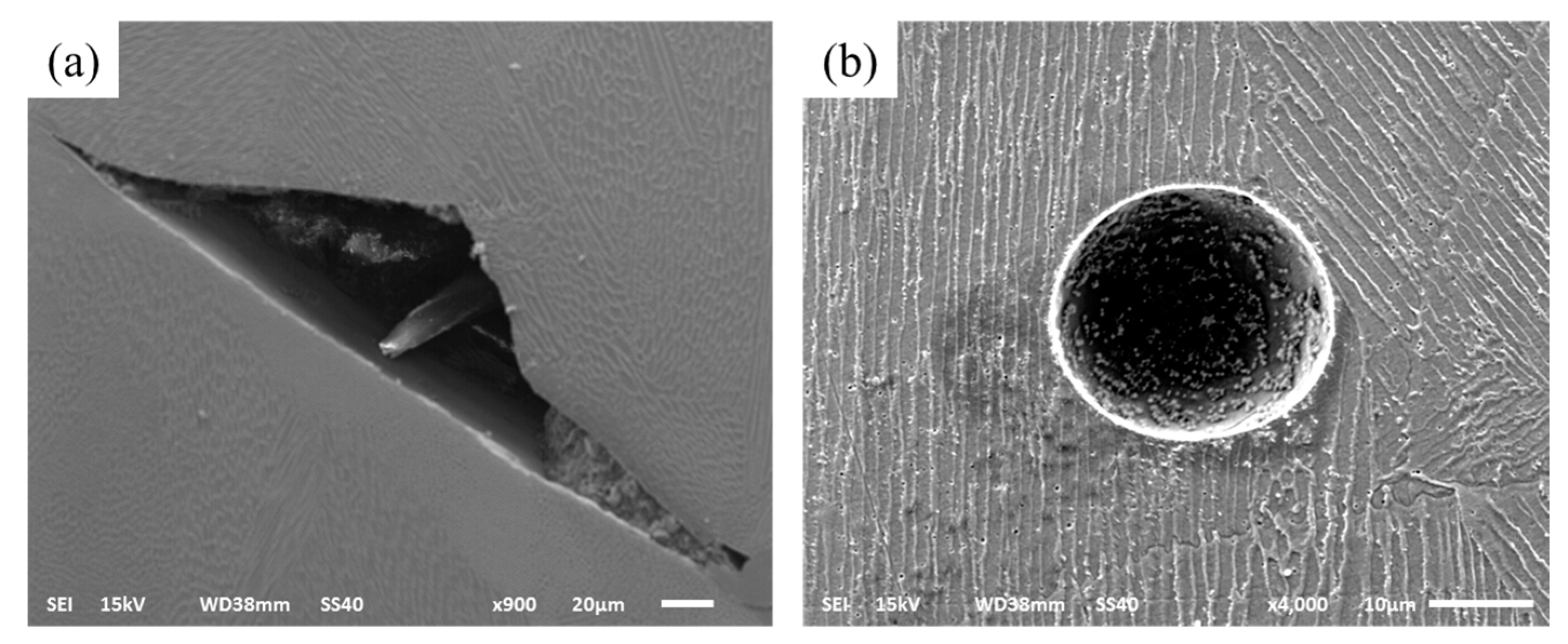

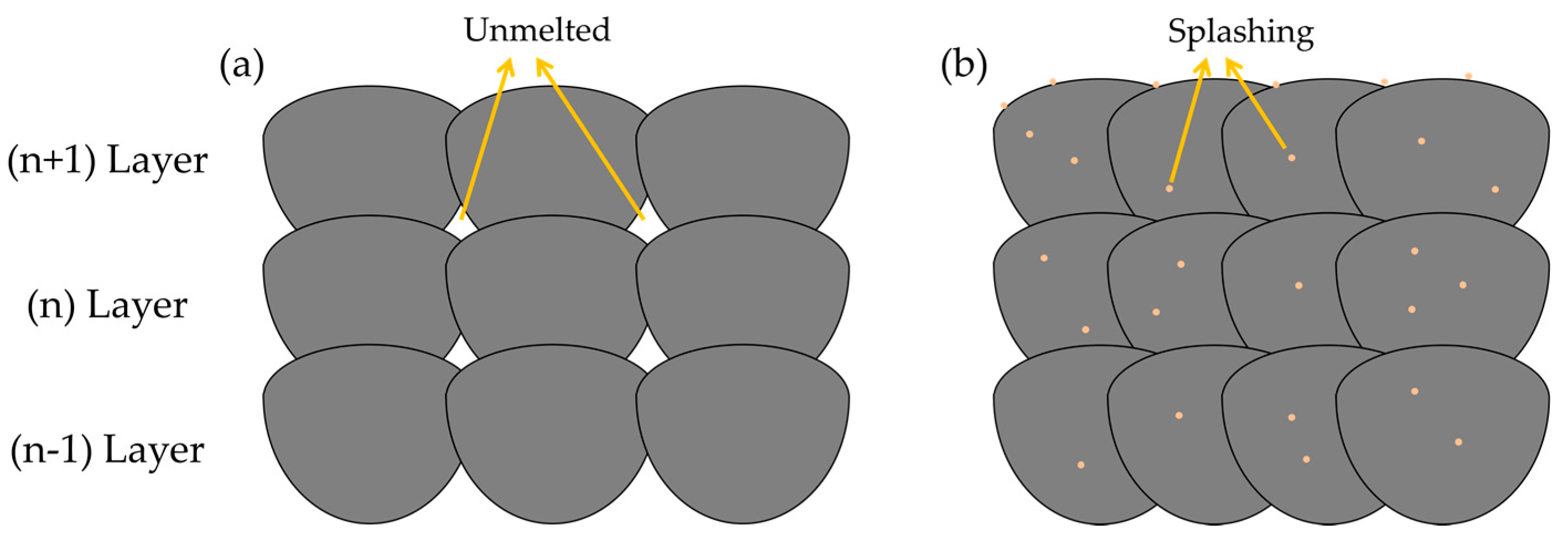

3.2.3. Analysis of Forming Defects

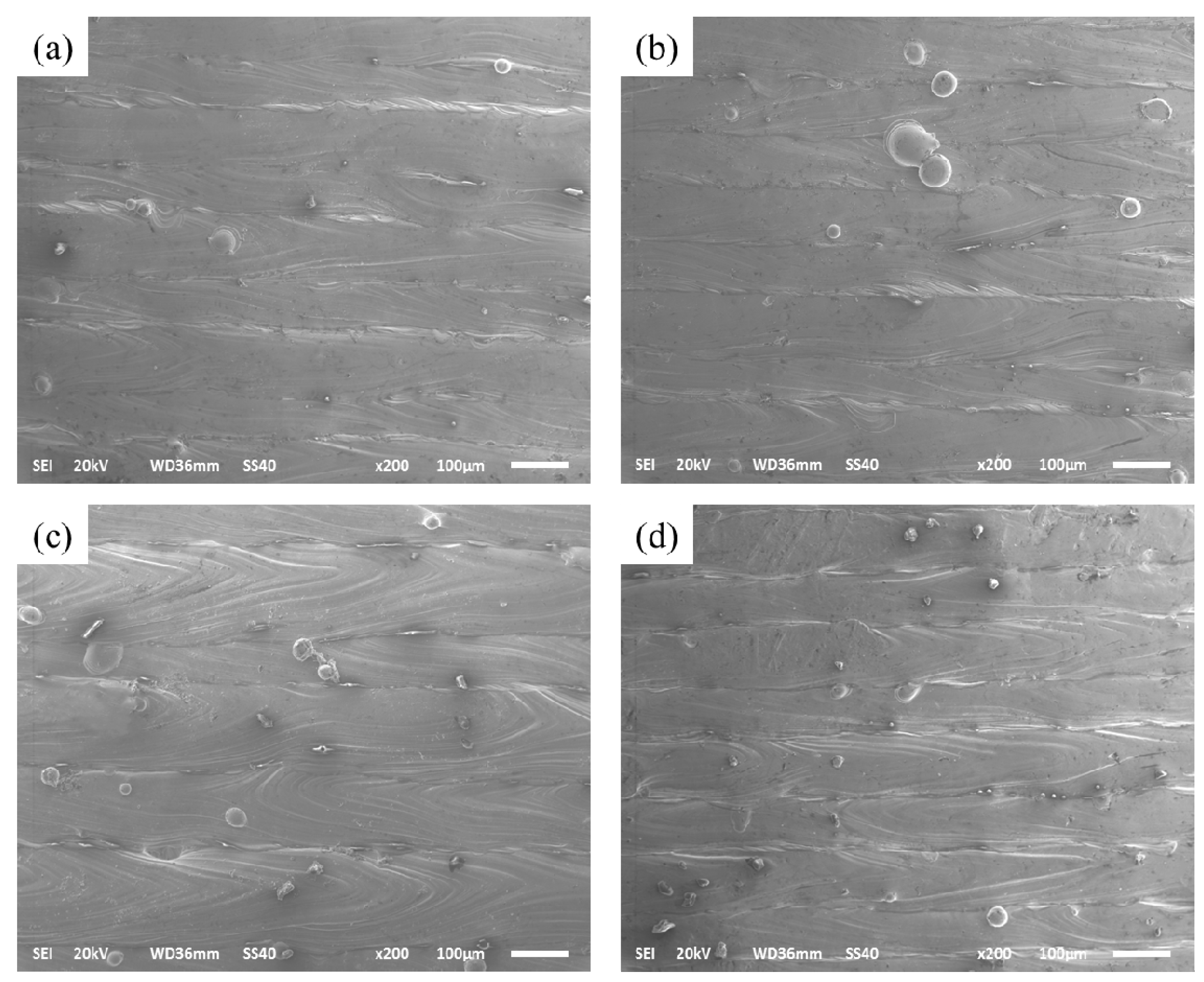

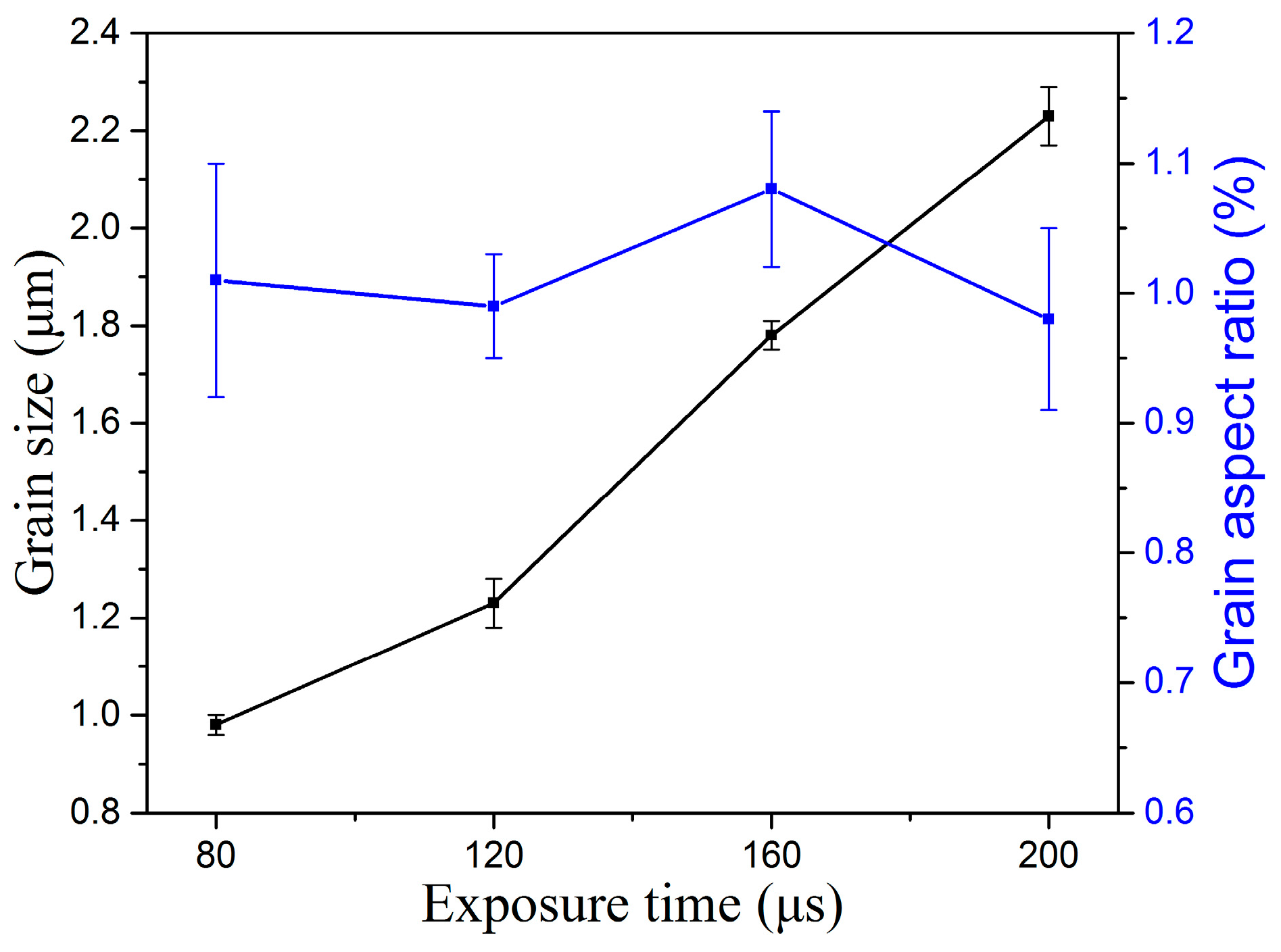

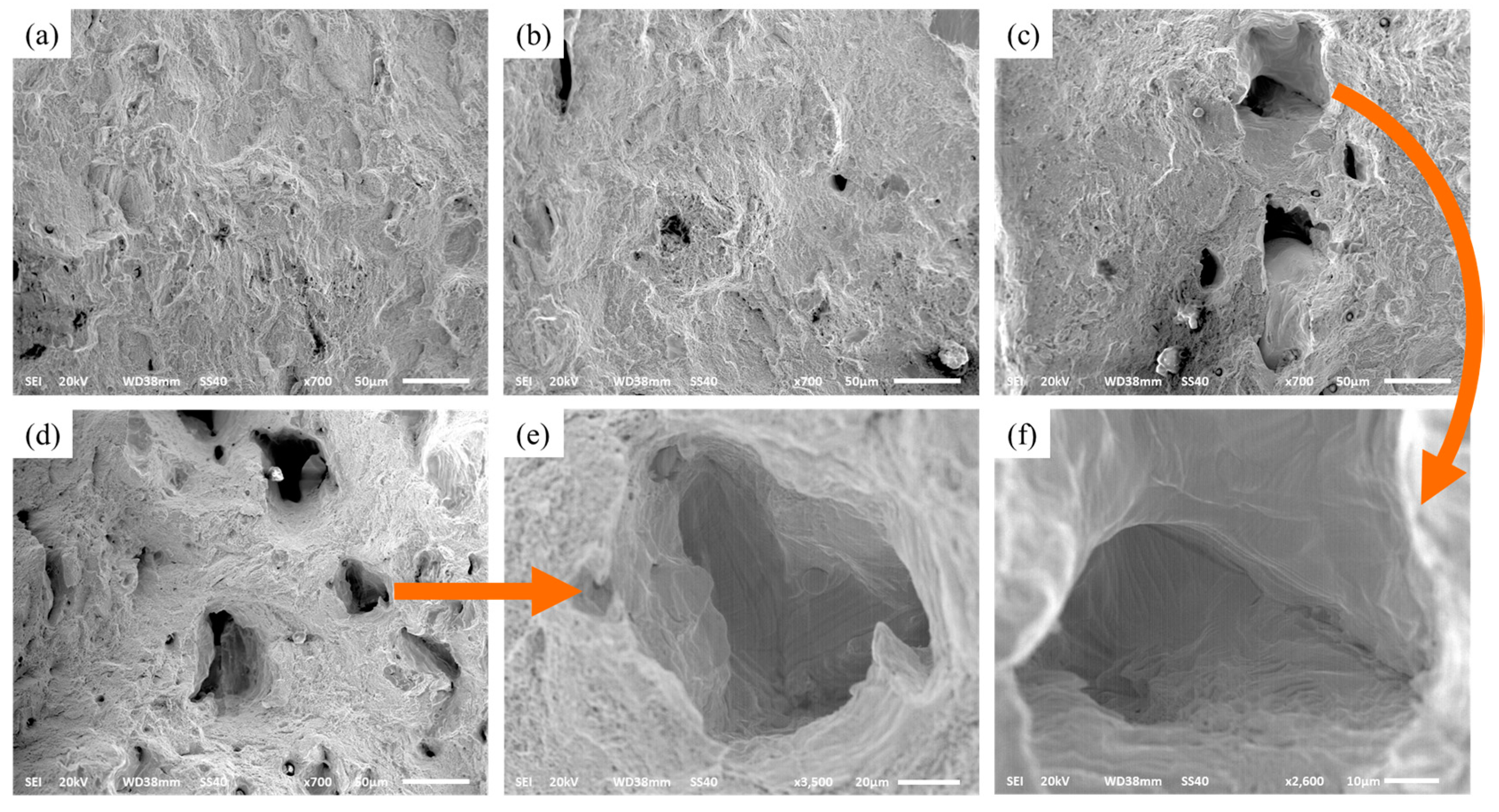

3.2.4. Microstructure

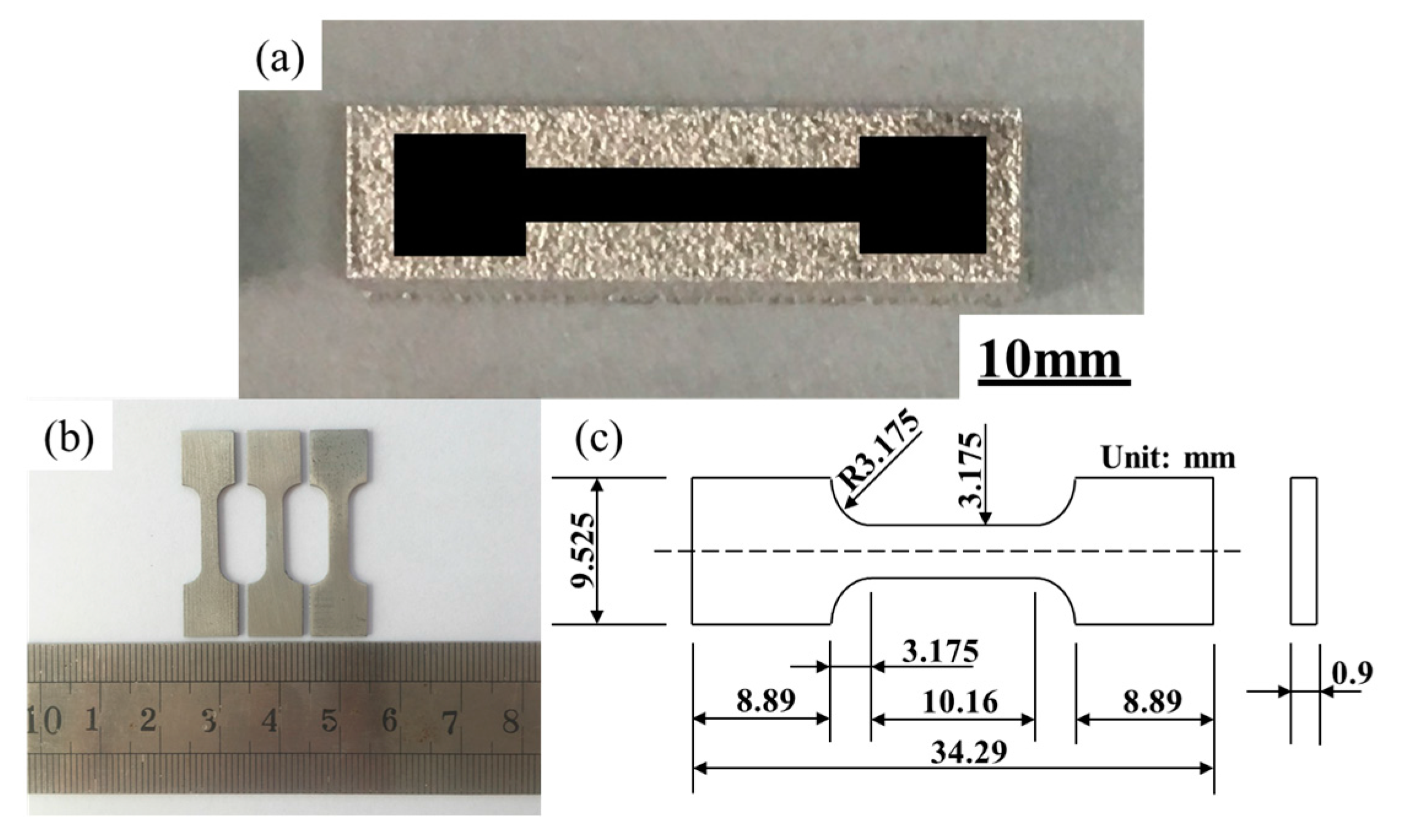

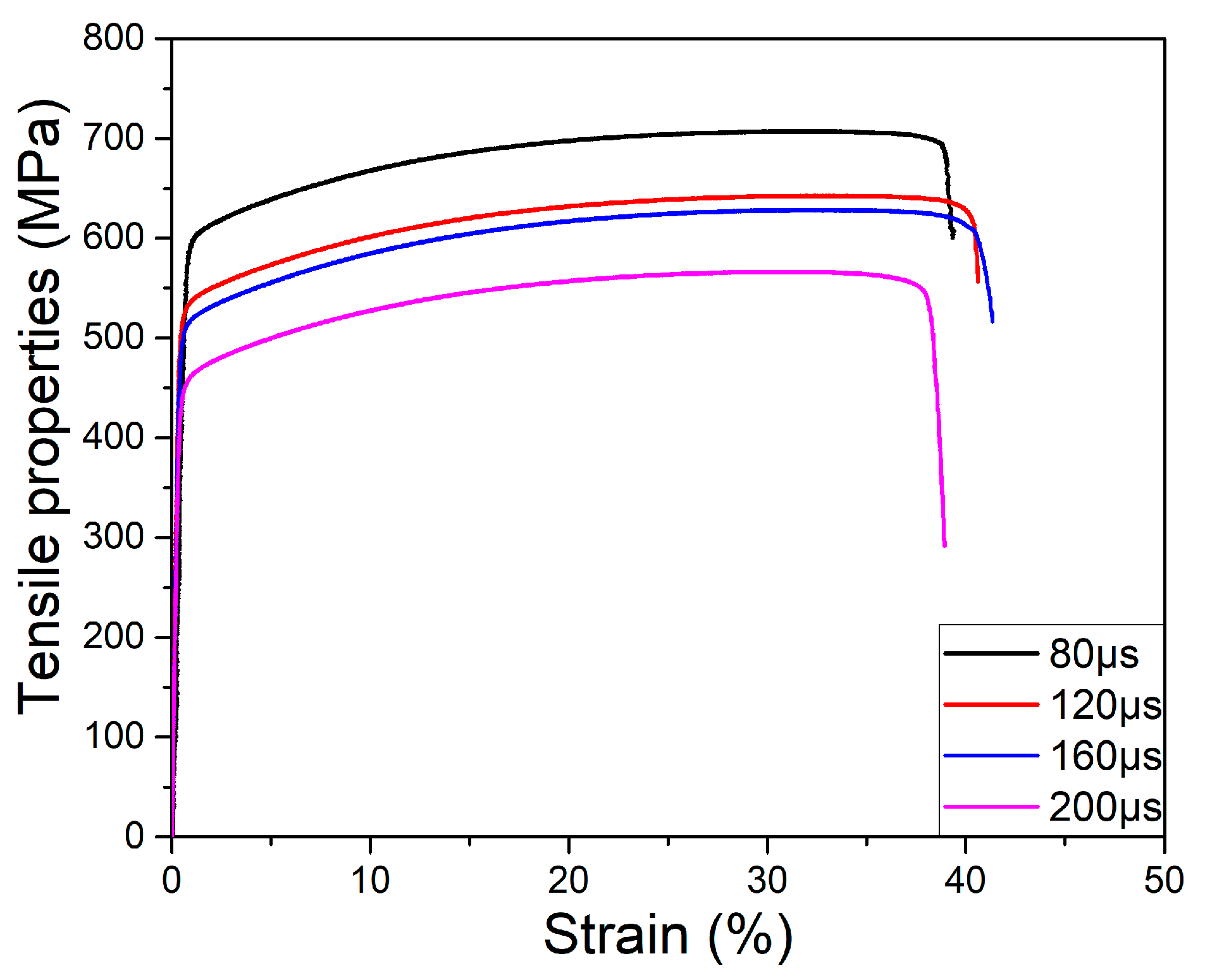

3.2.5. Tensile Properties

4. Conclusions

- Single-track experiments with different combinations of exposure times and point distances can effectively narrow down the selection windows.

- Multi-layer fabrications can be obtain approximation full-relative-density block ranges from 99.53% to 99.99%. The best relative density value can be reached at 99.99% when the process parameter of exposure time is 120 μs, the point distance is 40 μm, and the hatch space is 240 μm. The building rate can be up to 12 mm3/s, which is about 3 to 10 times higher than the previous studies.

- There are three typical defects: the un-melted defect between the molten pools, the micro-pore defect within the molten pool, and the irregular distribution of the splashing phenomenon. The un-melted defect, that has a huge influence on the relative density, can be completely eliminated by adjusting the process parameters. Micropore and splashing were caused by hollow powder, circulating gas, and splash slag with smaller influence on the relative density, which can be partly reduced (it is difficult to completely eliminate it only through adjusting process parameters).

- The microstructure of SLM high layer thickness fabricated indicates mostly fine equiaxed crystals and a small amount of columnar crystals because of a single molten pool with high degree of the subcooling. The average values of UTS, YS, and EL are 625 MPa, 525 MPa, and 39.9%, respectively, which are not significant difference in previous studies.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, X.-Y.; Fang, G.; Zhou, J. Additively manufactured scaffolds for bone tissue engineering and the prediction of their mechanical behavior: A review. Materials 2017, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokuldoss, P.K.; Kolla, S.; Eckert, J. Additive manufacturing processes: Selective laser melting, electron beam melting and binder jetting—Selection guidelines. Materials 2017, 10, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazier, W.E. Metal additive manufacturing: A review. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2014, 23, 1917–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Hao, L.; Hussein, A.; Young, P.; Raymont, D. Advanced lightweight 316L stainless steel cellular lattice structures fabricated via selective laser melting. Mater. Des. 2014, 55, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhong, Y.; Liu, L.; Wikman, S.; Cui, D.; Shen, Z. Intragranular cellular segregation network structure strengthening 316L stainless steel prepared by selective laser melting. J. Nucl. Mater. 2016, 470, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.F.; Gu, D.D.; Wu, P. Development of porous 316L stainless steel with controllable microcellular features using selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2013, 24, 1501–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, A.; Reginster, S.; Paydas, H.; Contrepois, Q.; Dormal, T.; Lemaire, O.; Lecomte-Beckers, J. Mechanical properties of alloy ti–6al–4v and of stainless steel 316L processed by selective laser melting: Influence of out-of-equilibrium microstructures. Powder Metall. 2014, 57, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Li, S.; Han, C.; Li, W.; Cheng, L.; Hao, L.; Shi, Y. Selective laser melting of stainless-steel/nano-hydroxyapatite composites for medical applications: Microstructure, element distribution, crack and mechanical properties. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2015, 222, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capek, J.; Machova, M.; Fousova, M.; Kubasek, J.; Vojtech, D.; Fojt, J.; Jablonska, E.; Lipov, J.; Ruml, T. Highly porous, low elastic modulus 316L stainless steel scaffold prepared by selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2016, 69, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Gu, D.; Yu, X. Preparation of honeycomb-like porous 316L stainless steel by selective laser melting. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2011, 40, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Shen, Y.F.; Gu, D.D. Development of porous 316L stainless steel with novel structures by selective laser melting. Powder Metall. 2013, 54, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, X. A comparison on metallurgical behaviors of 316L stainless steel by selective laser melting and laser cladding deposition. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 685, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemer, A.; Leuders, S.; Thöne, M.; Richard, H.A.; Tröster, T.; Niendorf, T. On the fatigue crack growth behavior in 316L stainless steel manufactured by selective laser melting. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2014, 120, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinhui, L.; Ruidi, L.; Wenxian, Z.; Liding, F.; Huashan, Y. Study on formation of surface and microstructure of stainless steel part produced by selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2013, 26, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, G.; Faria, S.; Bartolomeu, F.; Pinto, E.; Madeira, S.; Mateus, A.; Carreira, P.; Alves, N.; Silva, F.S.; Carvalho, O. Predictive models for physical and mechanical properties of 316L stainless steel produced by selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 657, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.; Mirzaeifar, R.; Moghaddam, N.S.; Turabi, A.S.; Karaca, H.E.; Elahinia, M. Effect of manufacturing parameters on mechanical properties of 316L stainless steel parts fabricated by selective laser melting: A computational framework. Mater. Des. 2016, 112, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casati, R.; Lemke, J.; Vedani, M. Microstructure and fracture behavior of 316L austenitic stainless steel produced by selective laser melting. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2016, 32, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Chen, J. Effects of scanning speed on in vitro biocompatibility of 316L stainless steel parts elaborated by selective laser melting. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Petrinic, N.; Siviour, C.R. Deformation behaviour of stainless steel microlattice structures by selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 614, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, C.; El-dasher, B.; Gallegos, G.F.; King, W.E.; Sisto, A. Density of additively-manufactured, 316L ss parts using laser powder-bed fusion at powers up to 400 w. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 74, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, J.A.; Davies, H.M.; Mehmood, S.; Lavery, N.P.; Brown, S.G.R.; Sienz, J. Investigation into the effect of process parameters on microstructural and physical properties of 316L stainless steel parts by selective laser melting. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 76, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Tan, X.; Tor, S.B.; Yeong, W.Y. Selective laser melting of stainless steel 316L with low porosity and high build rates. Mater. Des. 2016, 104, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Wang, Z.; Gao, M.; Zeng, X. Layer thickness dependence of performance in high-power selective laser melting of 1cr18ni9ti stainless steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2015, 215, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Ma, S.; Liu, C.; Chen, C.; Wu, Q.; Chen, X.; Lu, J. Performance of high layer thickness in selective laser melting of Ti6Al4V. Materials 2016, 9, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, L.; Dadbakhsh, S.; Sewell, N. Effect of selective laser melting layout on the quality of stainless steel parts. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2012, 18, 241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Yadroitsev, I.; Smurov, I. Selective laser melting technology: From the single laser melted track stability to 3d parts of complex shape. Phys. Procedia 2010, 5, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Gu, D. Tailoring surface quality through mass and momentum transfer modeling using a volume of fluid method in selective laser melting of tic/alsi10 mg powder. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2015, 88, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, S.A.; Anderson, A. Mesoscopic simulation model of selective laser melting of stainless steel powder. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2014, 214, 2627–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liu, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, L.; Jiang, W. Balling behavior of stainless steel and nickel powder during selective laser melting process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2011, 59, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Shi, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z. The key metallurgical features of selective laser melting of stainless steel powder for building metallic part. Powder Metall. Met. Ceramics 2011, 50, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunenthiram, V.; Peyre, P.; Schneider, M.; Dal, M.; Coste, F.; Fabbro, R. Analysis of laser–melt pool–powder bed interaction during the selective laser melting of a stainless steel. J. Laser Appl. 2017, 29, 022303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Jiang, W. Densification behavior of gas and water atomized 316L stainless steel powder during selective laser melting. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 256, 4350–4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wei, Q.S.; Lin, G.K.; Zhao, X.; Shi, Y.S. Effects of powder characteristics on selective laser melting of 316L stainless steel powder. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 189–193, 3664–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusarov, A.V.; Smurov, I. Modeling the interaction of laser radiation with powder bed at selective laser melting. Phys. Procedia 2010, 5, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Dembinski, L.; Coddet, C. The study of the laser parameters and environment variables effect on mechanical properties of high compact parts elaborated by selective laser melting 316L powder. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 584, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryawanshi, J.; Prashanth, K.G.; Ramamurty, U. Mechanical behavior of selective laser melted 316L stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 696, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Zhang, D.; Wei, P.; Zhang, K. Manufacturing feasibility and forming properties of Cu-4Sn in selective laser melting. Materials 2017, 10, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziętala, M.; Durejko, T.; Polański, M.; Kunce, I.; Płociński, T.; Zieliński, W.; Łazińska, M.; Stępniowski, W.; Czujko, T.; Kurzydłowski, K.J.; et al. The microstructure, mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of 316L stainless steel fabricated using laser engineered net shaping. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 677, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Zou, B.; Huang, C.; Gao, H. Study on microstructure, mechanical properties and machinability of efficiently additive manufactured aisi 316L. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2017, 2017, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wu, S.; Fu, F.; Mai, S.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Song, C. Mechanisms and characteristics of spatter generation in slm processing and its effect on the properties. Mater. Des. 2017, 117, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Mai, S.; Wang, D.; Song, C. Investigation into spatter behavior during selective laser melting of aisi 316L stainless steel powder. Mater. Des. 2015, 87, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, C.; Wu, Q.; Chen, X.; Lu, J. Wire arc additive manufacturing of az31 magnesium alloy: Grain refinement by adjusting pulse frequency. Materials 2016, 9, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.Z.; Wang, S.Z.; Li, B.L.; Yin, Z.M.; Wan, Q.; Liu, P. Grain growth and microstructure evolution based mechanical property predicted by a modified hall–petch equation in hot worked ni76cr19altico alloy. Mater. Des. 2014, 55, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, F.; Chen, D. A unified model for the prediction of yield strength in particulate-reinforced metal matrix nanocomposites. Materials 2015, 8, 5138–5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertens, A.; Reginster, S.; Contrepois, Q.; Dormal, T.; Lemaire, O.; Lecomte-Beckers, J. Microstructures and mechanical properties of stainless steel aisi 316L processed by selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Forum 2014, 783–786, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Fe | Cr | Ni | Mo | Mn | Si | N | O | P | C | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt % | Balance | 16–18 | 10–14 | 2–3 | 2 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.045 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Parameter | Value | Increment |

|---|---|---|

| Laser Power | 380 W | - |

| Exposure time | 80–200 μs | 40 μs |

| Point distance | 20–50 μm | 10 μm |

| Layer thickness | 150 μm | - |

| Laser beam spot size | 150 μm | - |

| Atmosphere | Oxygen target <200 ppm | - |

| Exposure Time (μs) | Point Distance (μm) | Hatch Space (μm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80 | 20 | 120 | 160 | 200 | 240 |

| 120 | 40 | 160 | 200 | 240 | 280 |

| 160 | 30 | 200 | 240 | 280 | 320 |

| 200 | 50 | 240 | 280 | 320 | 360 |

| Layer Thickness (μm) | Particle Size of D50 (μm) | Relative Density (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 42 | 99.00 | Kamath [20] |

| 50 | 27 | 98.60 | Zhang [35] |

| 50 | 30 | 99.62 | Cherry [21] |

| 50 | 42 | 99.88 | Sun [22] |

| 80 | 36 | 99.80 | Ma [23] |

| 150 | 18 | 99.99 | In this research |

| Layer Thickness [μm] | Hatch Space [μm] | Scanning Speed [mm/s] | Exposure Time [μs] | Building Rate [mm3/s] | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 55 | 1600 | - | 2.64 | Kamath [20] |

| 50 | 124 | - | 125 | 2.48 | Cherry [21] |

| 30 | 450 | 15 | - | 0.90 | Zietala [38] |

| 50 | 110 | - | 80 | 4.13 | Casati [17] |

| 50 | 35 | 1500 | - | 1.67 | Sun [22] |

| 100 | 3000 | 8.34 | - | 3.60 | Guo [39] |

| 150 | 240 | - | 120 | 12.00 | In this research |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Shi, W.; Qi, B.; Yang, J.; Zhang, F.; Han, D.; Ma, Y. Research on High Layer Thickness Fabricated of 316L by Selective Laser Melting. Materials 2017, 10, 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10091055

Wang S, Liu Y, Shi W, Qi B, Yang J, Zhang F, Han D, Ma Y. Research on High Layer Thickness Fabricated of 316L by Selective Laser Melting. Materials. 2017; 10(9):1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10091055

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Shuo, Yude Liu, Wentian Shi, Bin Qi, Jin Yang, Feifei Zhang, Dong Han, and Yingyi Ma. 2017. "Research on High Layer Thickness Fabricated of 316L by Selective Laser Melting" Materials 10, no. 9: 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10091055