Uniaxial Tension Test of Slender Reinforced Early Age Concrete Members

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Materials and Mix Proportion of Concrete

| C: blast furnace slag cement (B) JIS R 5211 | |

| density | 3.04 g/cm3 |

| blaine fineness | 3770 cm2/g |

| setting time start-end | 3 h. 39 m.–4 h. 57 m. |

| comp. strength at 3day | 21.5 MPa |

| at 7day | 37.7 MPa |

| at 28day | 63.2 MPa |

| S: fine aggregate (sea sand) | |

| density | 2.56 g/cm3 |

| maximum size | 5 mm |

| absorption | 1.3 % |

| G: coarse aggregate (crushed andesite rock) | |

| density | 2.73 g/cm3 |

| max. / min. size | 20/5 mm |

| absorption | 0.6% |

| Ad: chemical admixture (AE water reducing agent) | |

| standard amount for use | 1.0% vs cement weight |

| density | 1.08 g/cm3 |

| Water cement ratio (W/C) | 0.57 (57%) |

| Water W | 165 kg/m3 |

| Blast furnace slag cement C | 290 kg/m3 |

| Fine aggregate S | 812 kg/m3 |

| Coarse aggregate G | 1030 kg/m3 |

| Admixture Ad | 2.9 kg/m3 |

| Air | 4.5% |

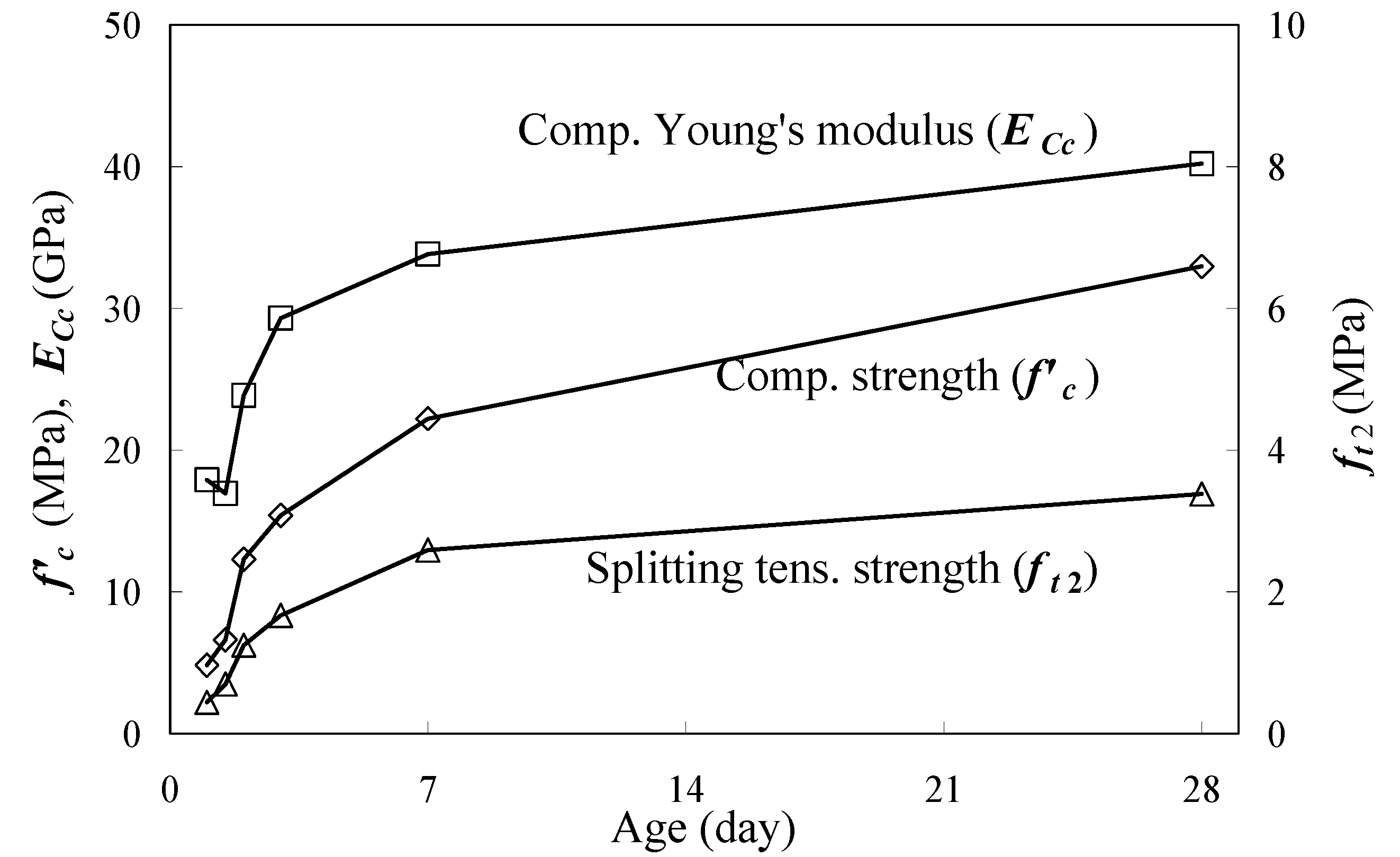

2.2. Mechanical Properties of Concrete

| Age (days) | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 28 |

| Compressive strength test* | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Splitting tensile test** | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Uniaxial tension test*** | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

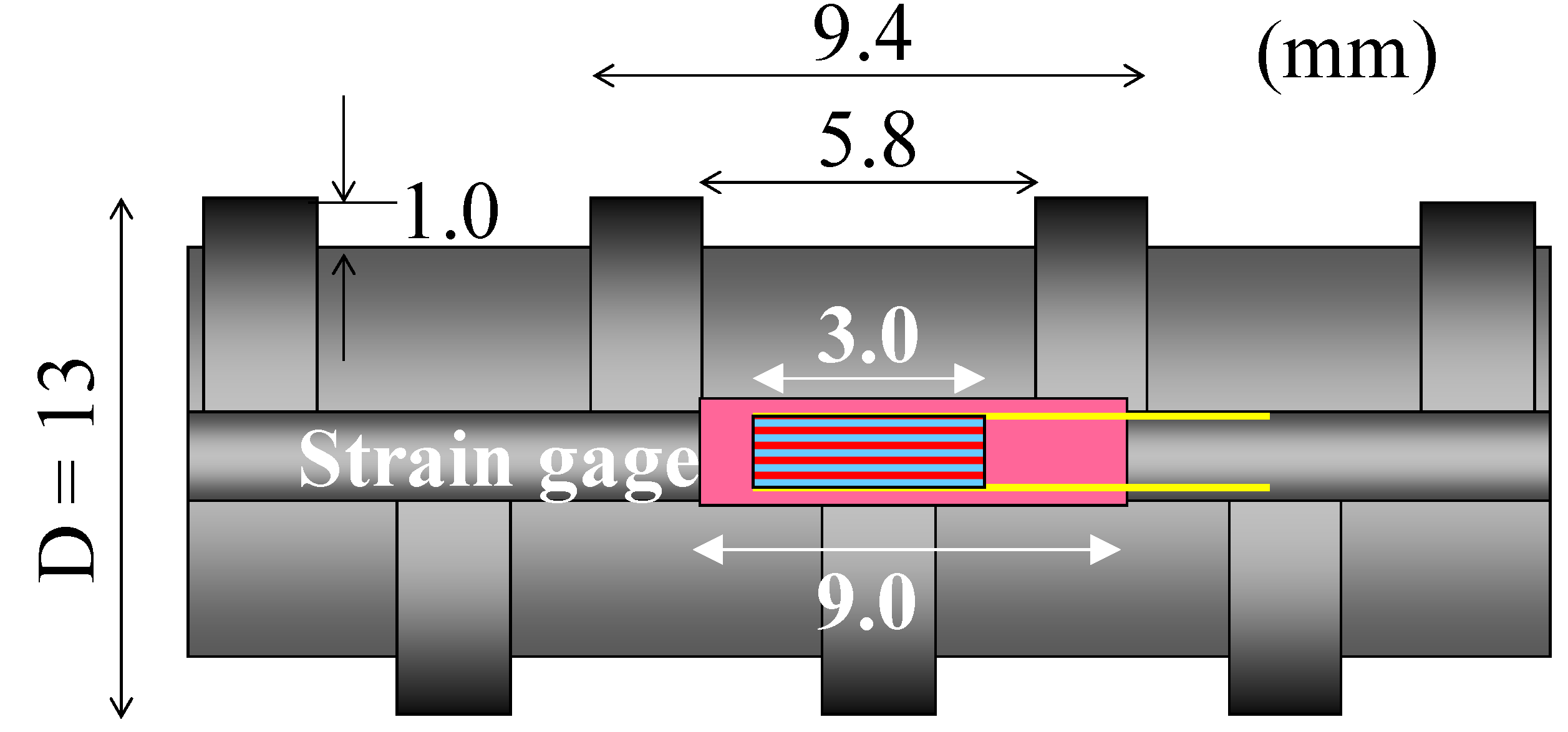

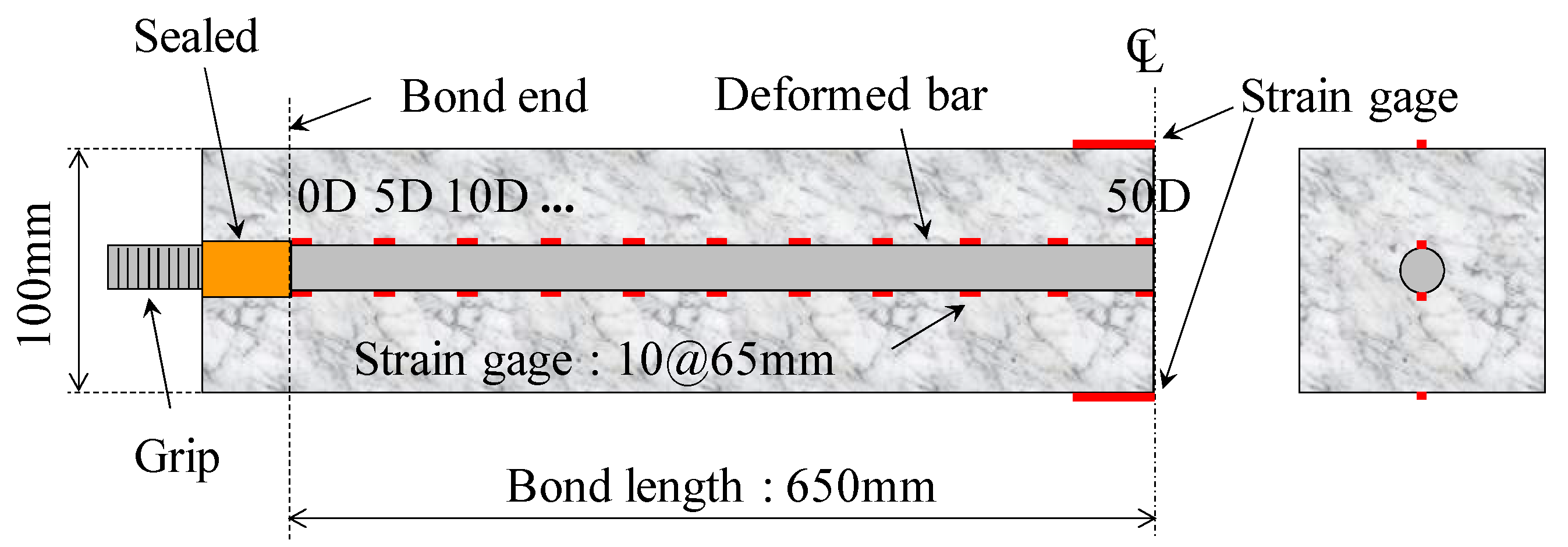

2.3. RC Specimen

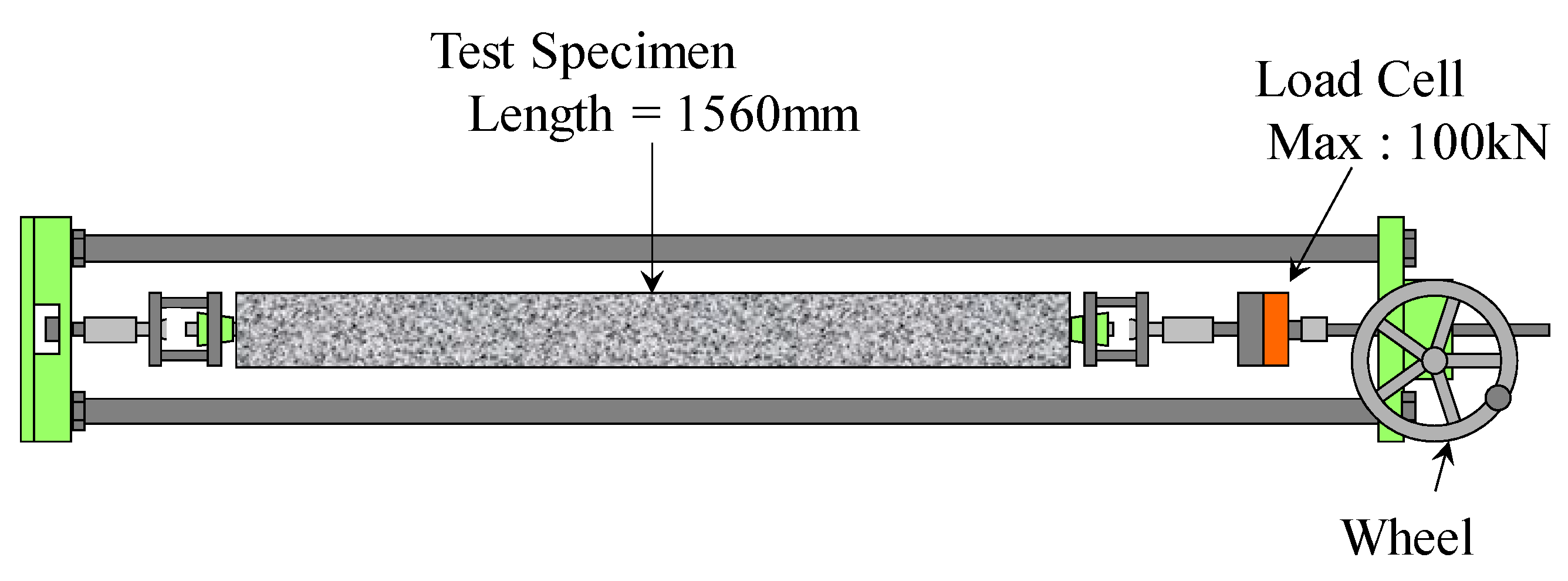

2.4. Uniaxial Tension Test

3. Cracking Behavior of Early Age Concrete

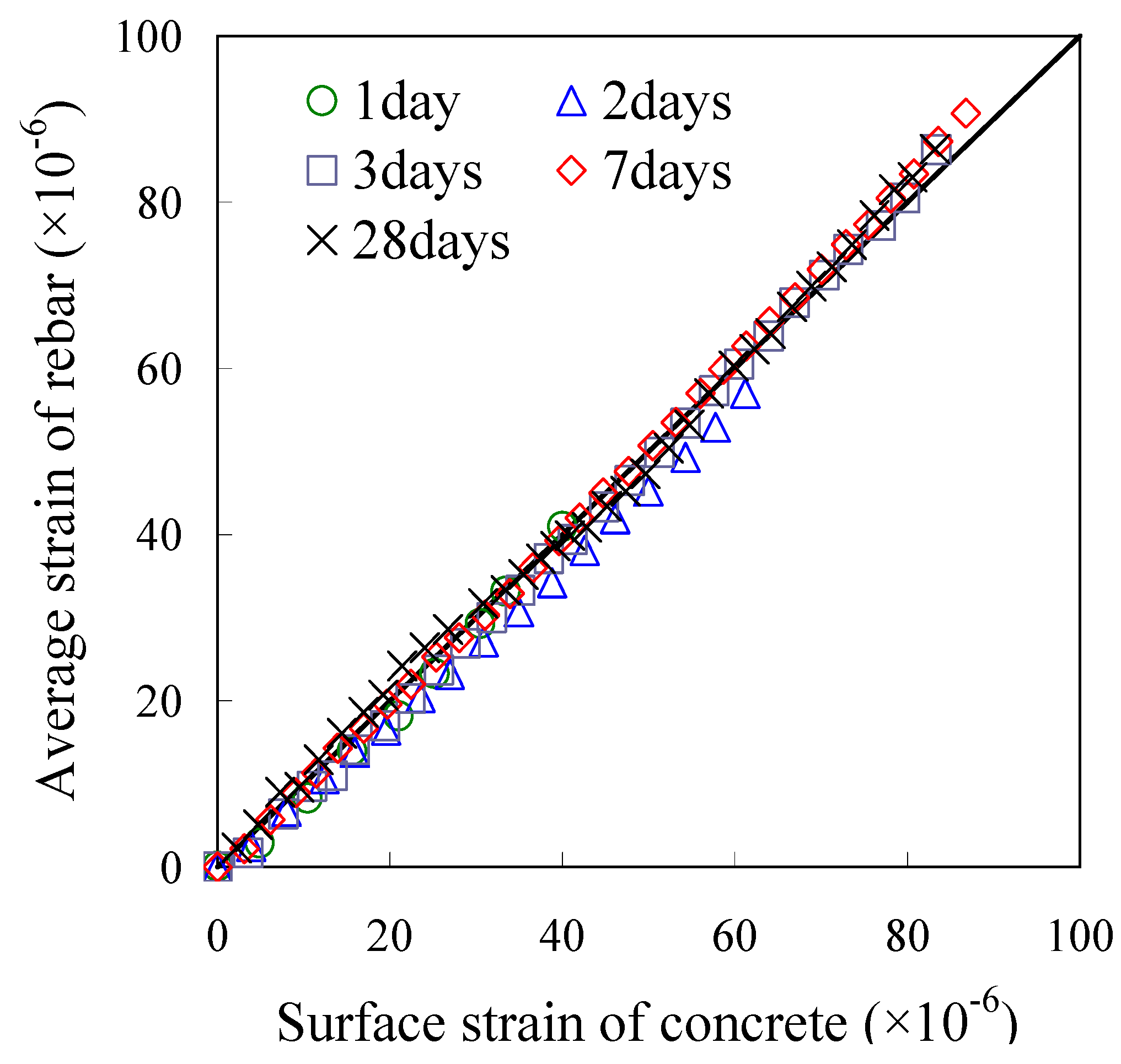

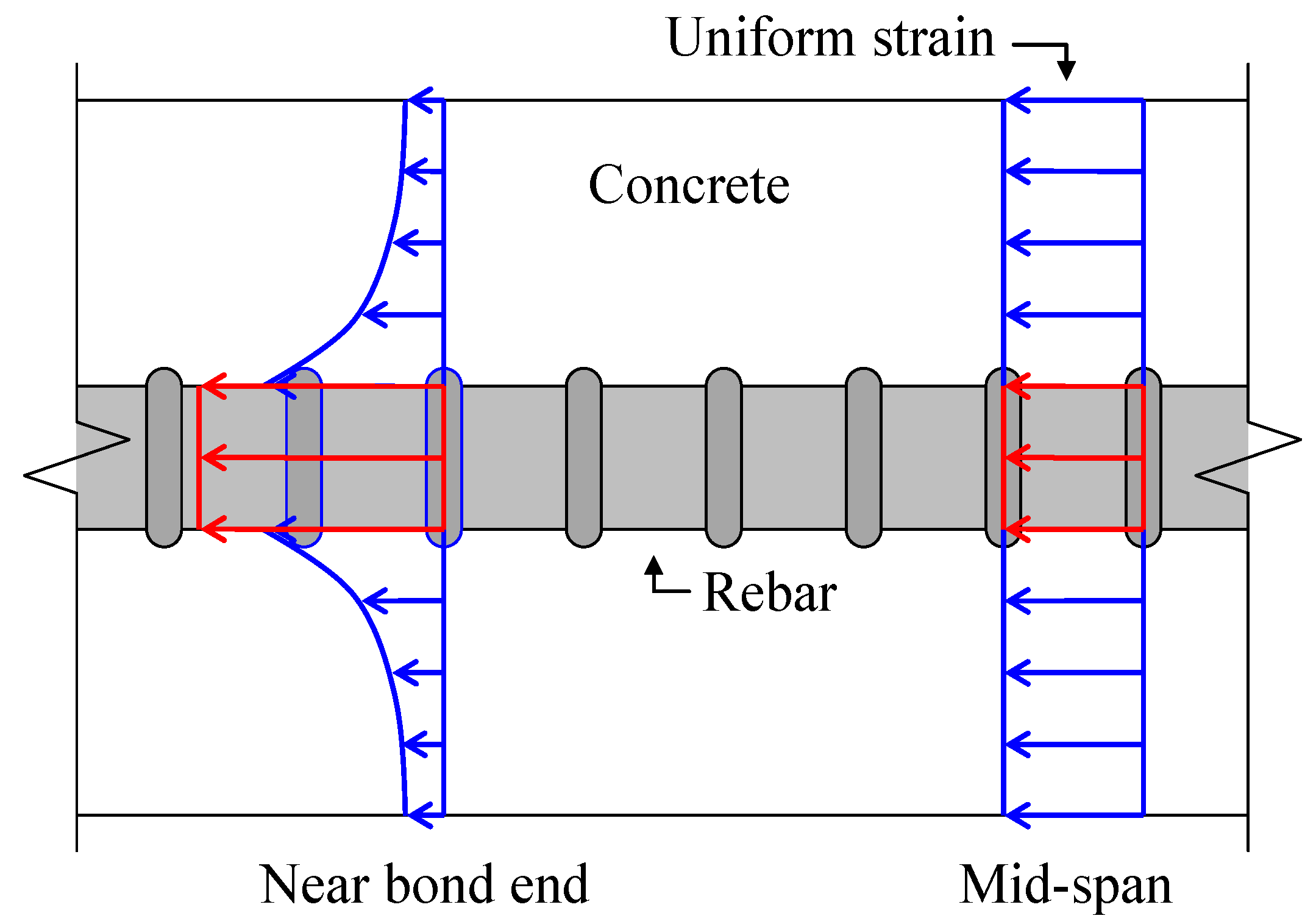

3.1. Evaluation Method for Stress of Concrete

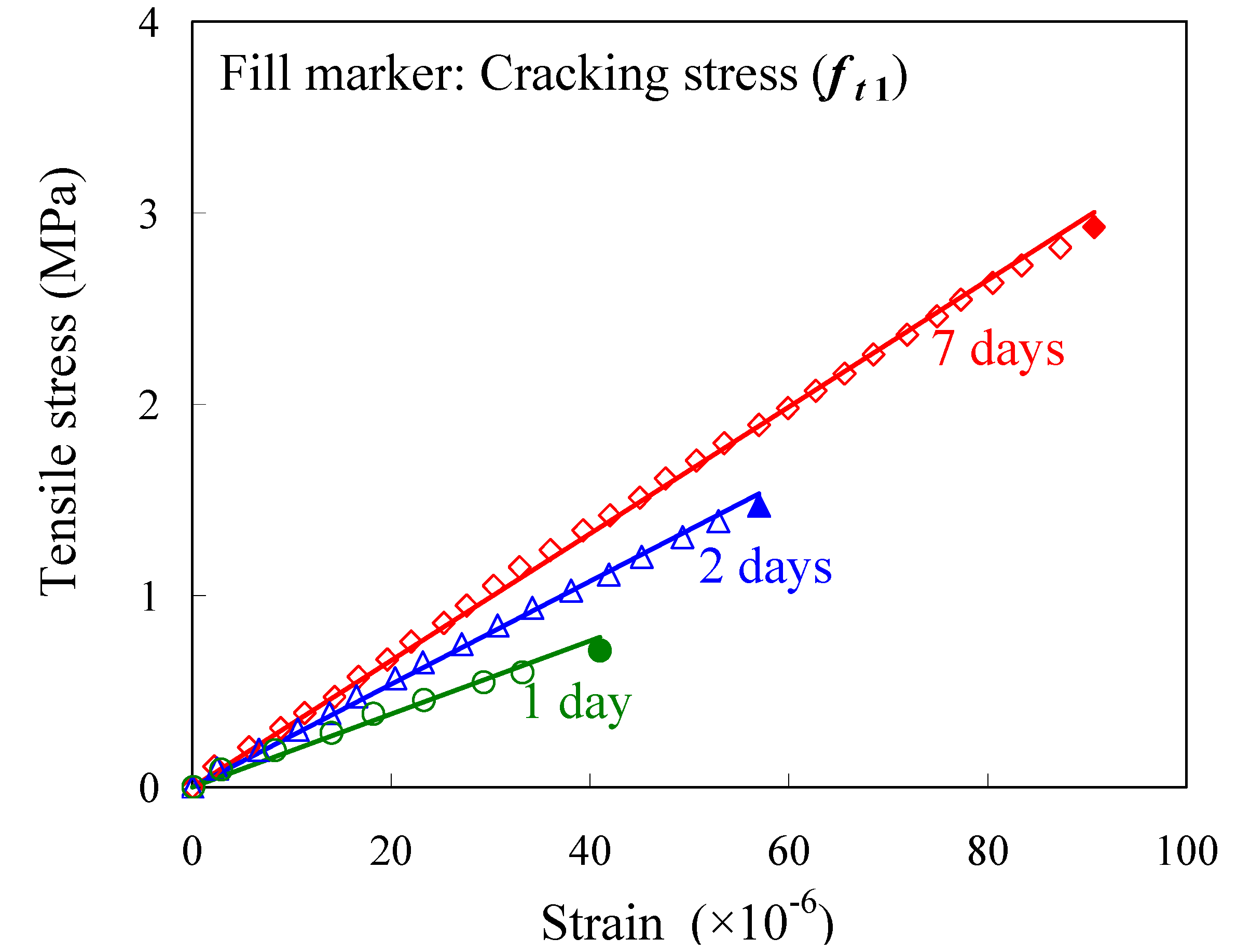

3.2. Tensile Stress-Strain Response

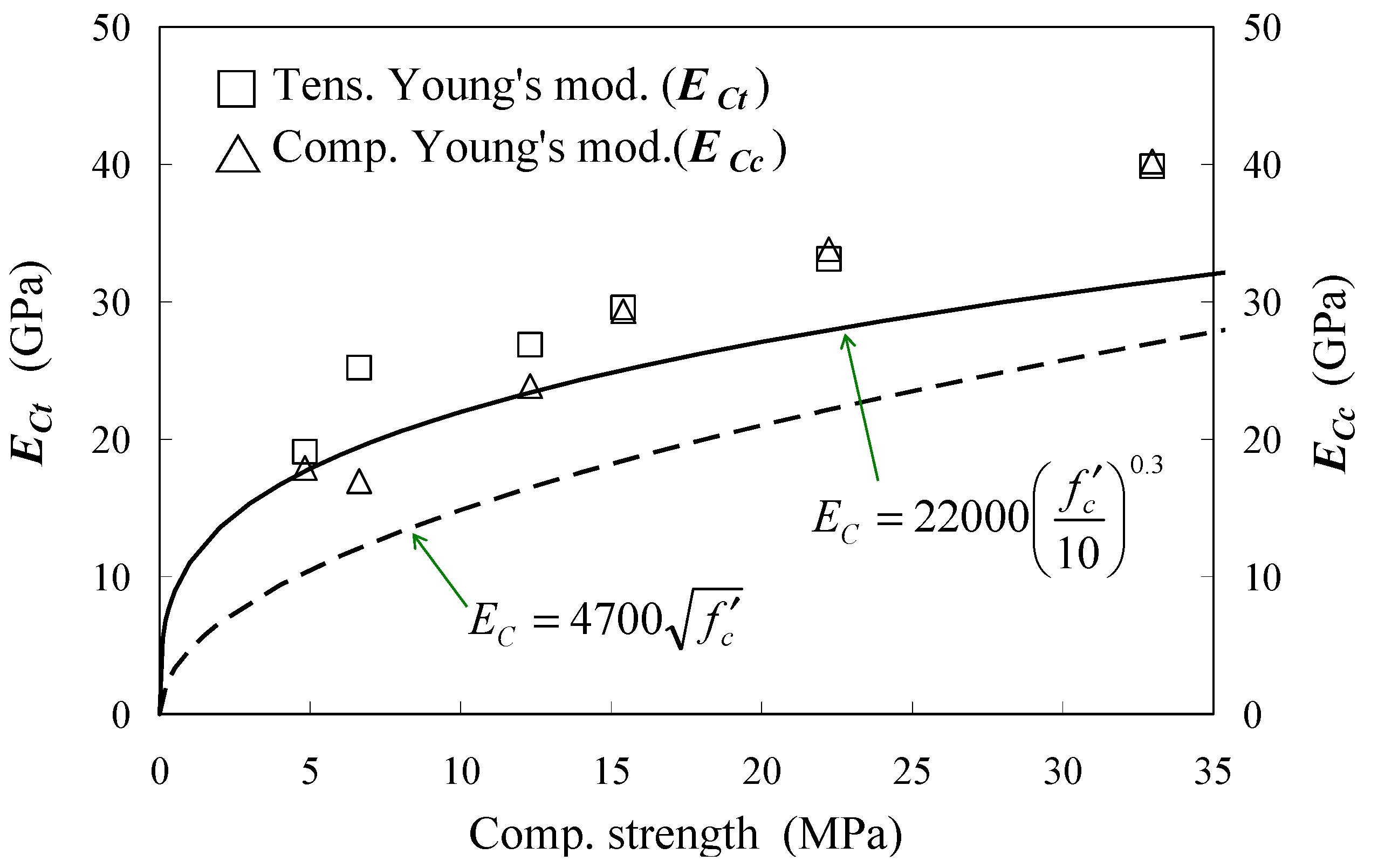

3.3. Tensile Young’s Modulus

3.4. Cracking Stress

3.5. Tensile Strain Capacity

| Age (days) | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 28 |

| Tens. strain capacity (×10−6) | -- | 41 | 54 | 57 | 86 | 91 | 86 |

| Cracking stress (MPa) | -- | 0.71 | 1.32 | 1.47 | 2.44 | 2.93 | 3.34 |

| Splitting tensile strength (MPa)* | -- | 0.44 | 0.70 | 1.25 | 1.67 | 2.59 | 3.38 |

| Comp. strength (MPa)* | 0.41 | 4.8 | 6.6 | 12.3 | 15.4 | 24.6 | 33.0 |

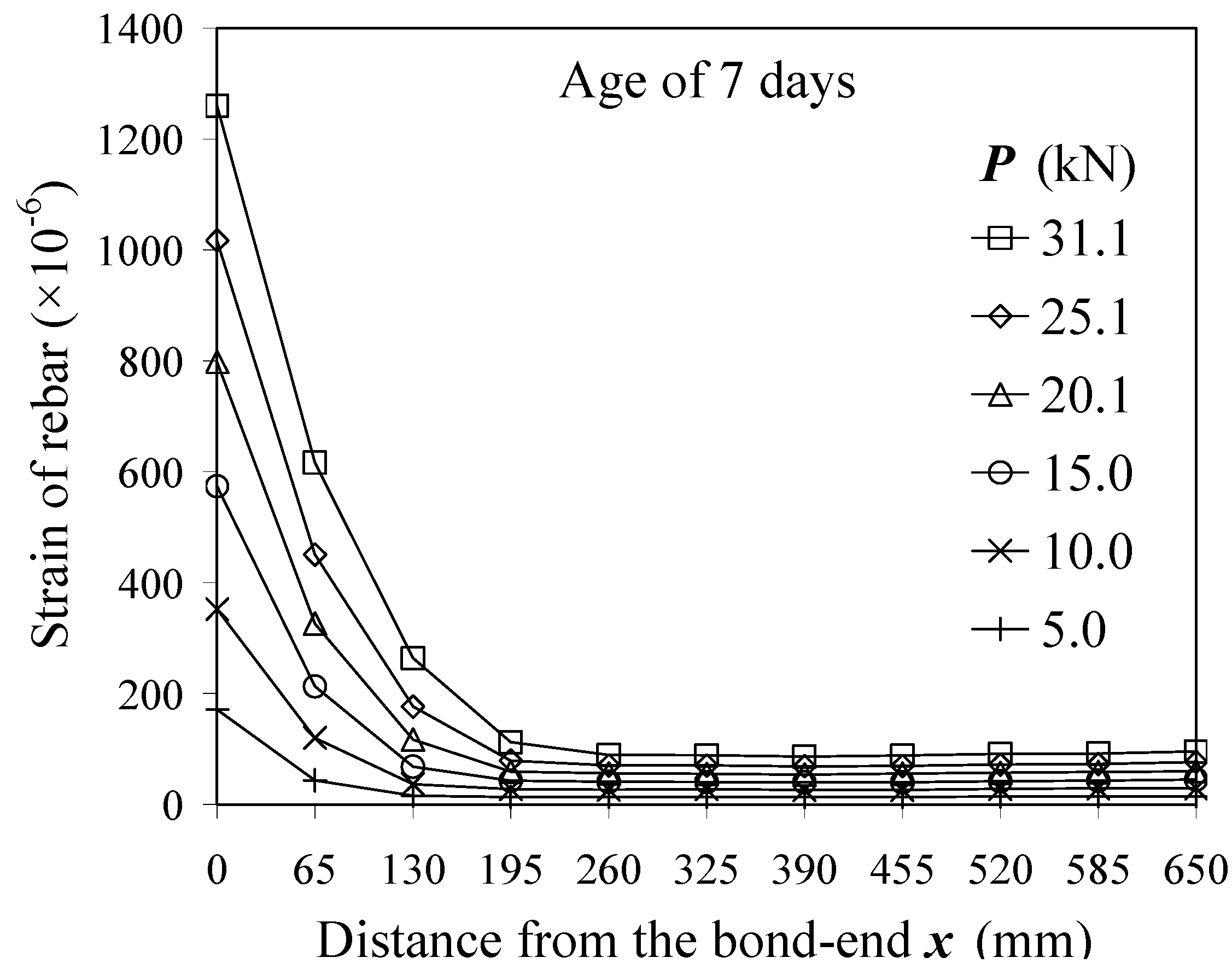

4. Bond Properties between Early Age Concrete and Deformed Bars

4.1. Evaluation Method for Bond and Slip

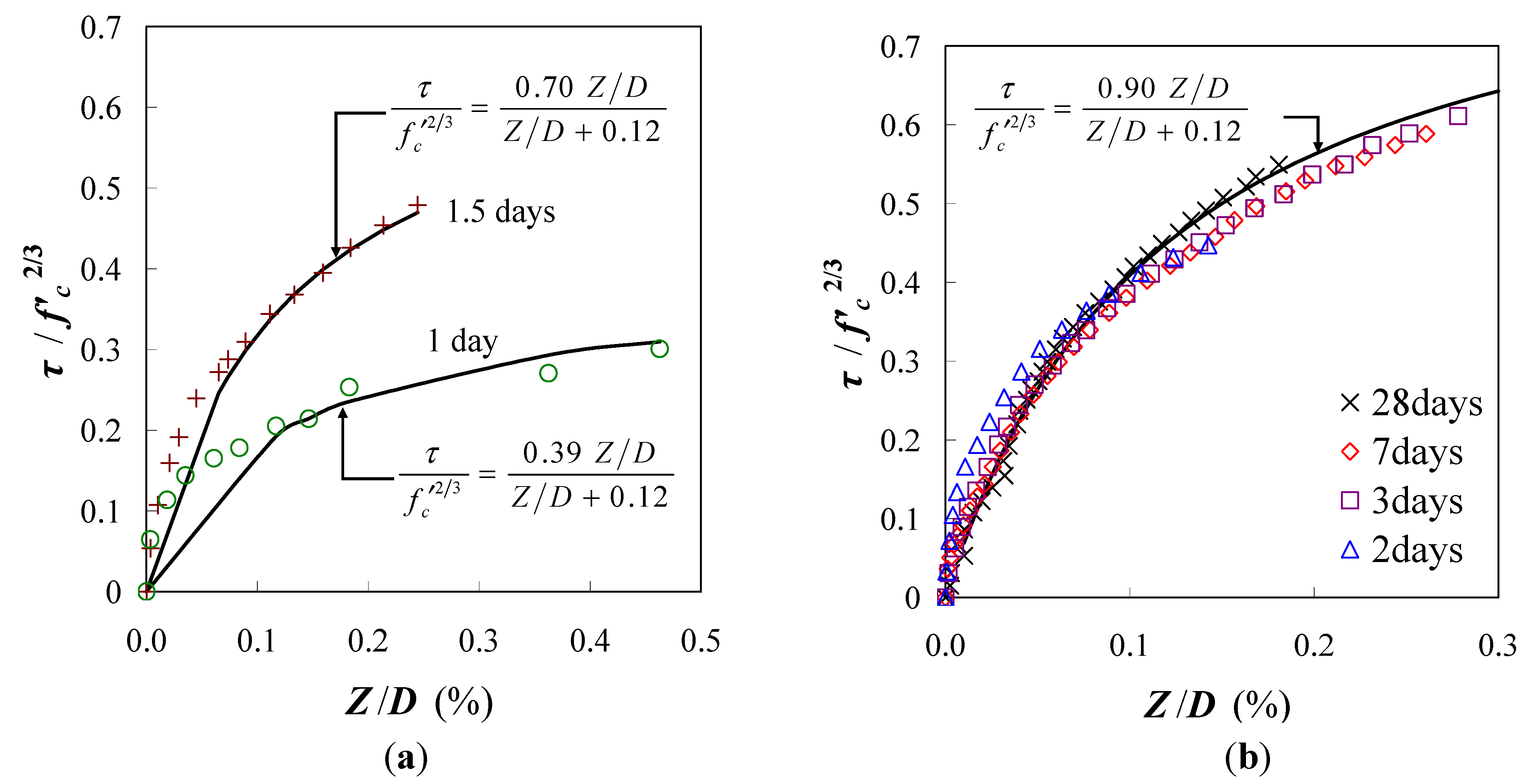

4.2. Bond Stress-Slip Relation

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Concrete strain can be estimated by using the strain of a rebar having a long embedment length. Tensile stress-strain responses of early age concrete are extremely linear.

- (2)

- Tensile Young’s modulus is higher than compressive modulus of early age concrete, and both moduli gradually become equal as hydration develops over time. The prediction formulae shown in the previous codes may underestimate tensile Young’s modulus of early age concrete.

- (3)

- The empirical equation for mature concrete can be applied to the relationship between uniaxial tensile strength and splitting tensile strength even in early age concrete.

- (4)

- Bond behaviors after the age of 2 days are almost equal, so an equation can be applied to this behavior. The empirical equation based on the test is proposed in the paper.

Acknowledgements

References

- JCI Committee on Computer Code Development for Crack Control in Massive Concrete; JCMAC3. JCI Committee: Tokyo, Japan, 2009. Available online: http://civil.design.csse.yamaguchi-u.ac.jp/masscon/index.html (accessed on 26 July 2011).

- ACI 231-10. Report on Early-Age Cracking: Causes, Measurement, and Mitigation; ACI: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom, S.G.; Byfors, J. Properties of concrete at early age. Mater. Struct. 1979, 13, 265–274. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, D.L. Determining tensile strain capacity of mass concrete. ACI J. 1976, 73, 691–700. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X; Li, Z. Investigation on mechanical properties of young concrete. Mater. Struct. 2000, 33, 627–633. [Google Scholar]

- Hagihara, S.; Nakamura, S.; Masuda, Y.; Kono, M. Experimental study on mechanical properties and creep behavior of high-strength concrete in early age. Concr. Res. Technol. 2000, 11, 39–50. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, Y.; Shimano, K.; Iijima, D.; Hirano, Y. Examination on simple uniaxial tensile test of concrete. Proc. Jpn. Concr. Inst. 2007, 29, 531–536. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Yoshitake, I.; Ishikawa, Y.; Kawano, H.; Mimura, Y. On the tensile Young’s moduli of early age concrete. J. Mater. Concr. Struct. Pavements 2007, 63, 677–688. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaddiwudiwudhipong, S.; Lu, H.; Wee, T. Direct tension test and tensile strain capacity of concrete at early age. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 2077–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, Y.; Yi, S. Fracture characteristics of concrete at early age. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, R.A.; Shah, S.P. Early-age bond strength in reinforced concrete. ACI Mater. J. 1987, 84, 501–510. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, B.P.; Videla, C. Design criteria for early-age bond strength in reinforced concrete. Mater. Struct. 1992, 25, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sule, M.; Breugel, K. Cracking behavior of reinforced concrete subjected to early-age shrinkage. Mater. Struct. 2001, 34, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sule, M.; Breugel, K. The effect of reinforcement on early-age cracking due to autogenous shrinkage and thermal effects. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2004, 26, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JIS-R-5211-2003 Portland Blast-Furnace Slag Cement; Japan Industrial Standard, JISC: Tokyo, Japan, 2003. (in Japanese)

- JIS-G-3112 Steel Bars for Concrete Reinforcement; Japan Industrial Standard, JISC: Tokyo, Japan, 2004. (in Japanese)

- JIS-A-1108 Method of Test for Compressive Strength of Concrete; Japan Industrial Standard, JISC: Tokyo, Japan, 2006. (in Japanese)

- JIS-A-1149 Method of Test for Static Modulus of Elasticity of Concrete; Japan Industrial Standard, JISC: Tokyo, Japan, 2001. (in Japanese)

- JIS-A-1113 Method of Test for Splitting Tensile Strength of Concrete; Japan Industrial Standard, JISC: Tokyo, Japan, 2006. (in Japanese)

- JSCE. Standard Specifications for Concrete Structures-2007, 1st ed.; Japan Society for Civil Engineers: Tokyo, Japan, 2007. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- ACI 318-08. Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary; ACI: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures. Part 1—General Rules and Rules for Buildings, German version EN 1992-1-1:2004 + AC:2010; The Concrete Centre: Blackwater, Camberley, UK, 2002. Available online: http://www.concretecentre.com/codes__standards/eurocodes/eurocode_2.aspx (accessed on 26 July 2011).

- Yoshimoto, A. Deformation and Fracture of Concrete, 1st ed.; Gakkensya: Tokyo, Japan, 1990; pp. 143–144. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.C.; McDonald, J.E. Prediction of tensile strain capacity of mass concrete. ACI J. 1978, 75, 192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Mimura, Y.; Yoshitake, I.; Morimoto, K.; Hamada, S. Experimental study on local bond characteristics of deformed bar embedded in early-age concrete. J. Mater. Concr. Struct. Pavements 2007, 63, 410–423. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamao, Y.; Chou, L.; Niwa, J. Experimental study of local bond-slip relationship. J. JSCE 1984, 343, 219–228. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Shima, H.; Chou, L.; Okamura, H. Bond-slip-strain relationship of deformed bars embedded in massive concrete. J. Mater. Concr. Struct. Pavements 1987, 378, 165–174. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Mimura, Y.; Yoshitake, I.; Zhang, W. Uniaxial Tension Test of Slender Reinforced Early Age Concrete Members. Materials 2011, 4, 1345-1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma4081345

Mimura Y, Yoshitake I, Zhang W. Uniaxial Tension Test of Slender Reinforced Early Age Concrete Members. Materials. 2011; 4(8):1345-1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma4081345

Chicago/Turabian StyleMimura, Yoichi, Isamu Yoshitake, and Wenbo Zhang. 2011. "Uniaxial Tension Test of Slender Reinforced Early Age Concrete Members" Materials 4, no. 8: 1345-1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma4081345