Permeation of Light Gases through Hexagonal Ice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Crystallization

2.2. Single-Crystal Permeation Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

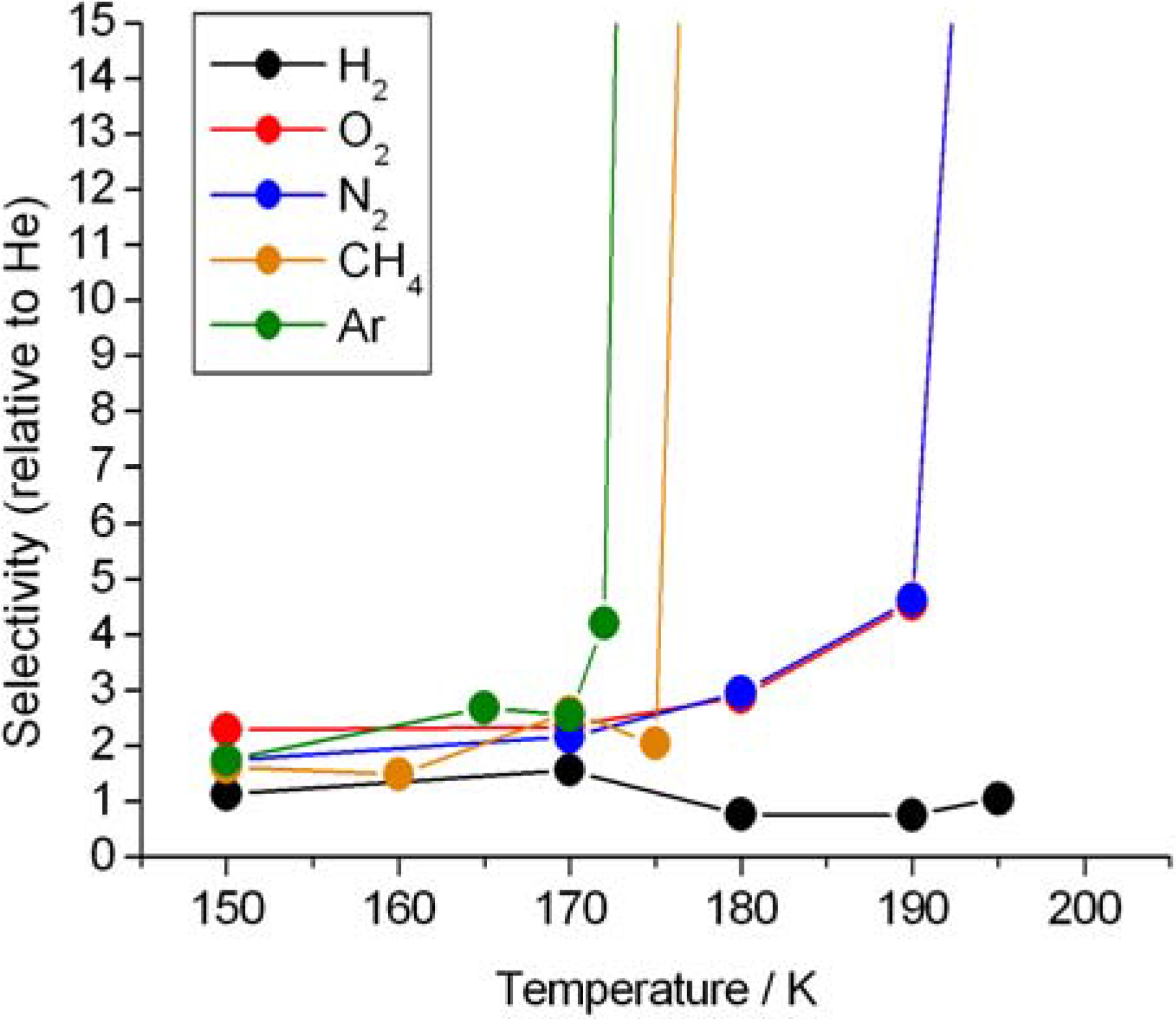

| Gas | Kinetic diameters (Å) | Gas excluding temperature (K) |

|---|---|---|

| Helium | 2.60 | >195 K |

| Hydrogen | 2.89 | >195 K |

| Oxygen | 3.46 | 195 K |

| Nitrogen | 3.64 | 195 K |

| Methane | 3.80 | 180 K |

| Argon | 3.40 | 175 K |

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Files

Supplementary File 1Acknowledgments

References

- Bernardo, P.; Drioli, E.; Golemme, G. Membrane gas separation: A review/state of the art. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 4638–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeson, L.M. The upper bound revisited. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 320, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bux, H.; Liang, F.; Li, Y.; Cravillon, J.; Wiebcke, M.; Caro, J. Zeolitic imidazolate framework membrane with molecular sieving properties by microwave-assisted solvothermal synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 16000–16001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, T.H.; Lee, J.S.; Qiu, W.; Koros, W.J.; Jones, C.W.; Nair, S. A high-performance gas-separation membrane containing submicrometer-sized metal-organic framework crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 9863–9866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatov, D.V.; Moudrakovski, I.L.; Ripmeester, J.A. Dipeptides as microporous materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 6308–6311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comotti, A.; Bracco, S.; Distefano, G.; Sozzani, P. Methane, carbon dioxide and hydrogen storage in nanoporous dipeptide-based materials. Chem. Commun. 2009, 3, 284–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, R.V.; Durão, J.; Mendes, A.; Damas, A.M.; Gales, L. Dipeptide crystals as excellent permselective materials: Sequential exclusion of argon, nitrogen, and oxygen. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 3034–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, R.; Mendes, A.; Gales, L. Peptide-based solids: Porosity and zeolitic behavior. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 1709–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameta, N.; Minamikawa, H.; Masuda, M. Supramolecular organic nanotubes: How to utilize the inner nanospace and the outer space. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 4539–4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L. The Structure and entropy of ice and of other crystals with some randomness of atomic arrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1935, 57, 2680–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatov, D.V.; Moudrakovski, I.L.; Grachev, E.V.; Ripmeester, J.A. Micropores in crystalline dipeptides as seen from the crystal structure, he pycnometry, and 129Xe NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6737–6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geil, B.; Kirschgen, T.M.; Fujara, F. Mechanism of proton transport in hexagonal ice. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72, 014304:1–014304:10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markland, T.E.; Manolopoulos, D.E. An efficient ring polymer contraction scheme for imaginary time path integral simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 129, 074501:1–074501:8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottger, K.; Endriss, A.; Ihringer, J.; Doyle, S.; Kuhs, W.F. Lattice constants and thermal expansion of H2O and D2O ice Ih between 10 and 265 K. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 1994, 50, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantl, G. Wärmeausdehnung von H2O- und D2O-einkristallen (In German). Z. Phys. 1962, 166, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhs, W.F.; Lehmann, M.S. The structure of ice Ih by neutron diffraction. J. Phys. Chem. 1983, 87, 4312–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhs, W.F.; Genov, G.; Staykova, D.K.; Hansen, T. Ice perfection and onset of anomalous preservation of gas hydrates. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2004, 6, 4917–4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, G.A. Comprehensive Supramolecular Chemistry; Atwood, J.L., Davies, J.E.D., MacNicol, D.D., Vogtle, F., Lehn, J.M., Eds.; Pergamon: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ripmeester, J.A.; Tse, J.S.; Ratcliffe, C.I.; Powell, B.M. A new clathrate hydrate structure. Nature 1987, 325, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udachin, K.A.; Ratcliffe, C.I.; Enright, G.D.; Ripmeester, J.A. Structure H hydrate: A single crystal diffraction study of 2,2-dimethylpentane·5(Xe, H2S)·34H2O. Supramol. Chem. 1997, 8, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Seo, Y.T.; Lee, J.W.; Moudrakovski, I.; Ripmeester, J.A.; Chapman, N.R.; Coffin, R.B.; Gardner, G.; Pohlman, J. Complex gas hydrate from the Cascadia margin. Nature 2007, 445, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavi, S.; Ripmeester, J.A. Hydrogen-gas migration through clathrate hydrate cages. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 6102–6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeya, S.; Ripmeester, J.A. Dissociation behavior of clathrate hydrates to ice and dependence on guest molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 1276–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fray, N.; Marboeuf, U.; Brissaud, O.; Schmitt, B. Equilibrium data of methane, carbon dioxide, and xenon clathrate hydrates below the freezing point of water. Applications to astrophysical environments. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2010, 55, 5101–5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, T.A.; Somayazulu, M.; Hemley, R.J. Phase behavior of H2 + H2O at high pressures and low temperatures. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 4898–4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch, V.; Devlin, J.P.; Monreal, I.A.; Jagoda-Cwiklik, B.; Uras-Aytemiz, N.; Cwiklik, L. Clathrate hydrates with hydrogen-bonding guests. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009, 11, 10245–10265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda-Fukazawa, T.; Horikawa, S.; Hondoh, T.; Kawamura, K. Molecular dynamics studies of molecular diffusion in ice Ih. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 3886–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda-Fukazawa, T.; Kawamura, K.; Hondoh, T. Diffusion of nitrogen gas in ice Ih. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 385, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda-Fukazawa, T.; Kawamura, K.; Hondoh, T. Mechanism of molecular diffusion in ice crystals. Mol. Simulat. 2004, 30, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demurov, A.; Radhakrishnan, R.; Trout, B.L. Computations of diffusivities in ice and CO2 clathrate hydrates via molecular dynamics and Monte Carlo simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 116, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitlin, S.; Lemak, A.S.; Torrie, B.H.; Leung, K.T. Surface adsorption and trapping of Xe on hexagonal ice at 180 K by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 9958–9963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.; Zimmermann, N.E.R.; Beckham, G.T.; Tester, J.W.; Trout, B.L. Path sampling calculation of methane diffusivity in natural gas hydrates from a water-vacancy assisted mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 17342–17350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballenegger, V.; Picaud, S.; Toubin, C. Molecular dynamics study of diffusion of formaldehyde in ice. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 432, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, A.; Hondoh, T. Theoretical study on the diffusion of gases in hexagonal ice by the molecular orbital method. Can. J. Phys. 2003, 81, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, J.; Klinger, J. Adsorption of N2 and CO2 on ice. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1982, 86, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, T.A.; Boxe, C.; Goddard, W.A. An inexpensive, widely available material for 4 wt% reversible hydrogen storage near room temperature. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 1417–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamoto, T.; Tasaki, Y.; Okada, T. Chiral ice chromatography. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 13135–13137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Durão, J.; Gales, L. Permeation of Light Gases through Hexagonal Ice. Materials 2012, 5, 1593-1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma5091593

Durão J, Gales L. Permeation of Light Gases through Hexagonal Ice. Materials. 2012; 5(9):1593-1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma5091593

Chicago/Turabian StyleDurão, Joana, and Luis Gales. 2012. "Permeation of Light Gases through Hexagonal Ice" Materials 5, no. 9: 1593-1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma5091593