Biodegradable Materials for Bone Repair and Tissue Engineering Applications

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Biodegradable Materials

| Material Type | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Young’s Modulus (GPA) | Elongation (%) | Degradation Time (Months) | Loss of Total Strength (Months) | Applications for Bone Repair and Regeneration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Bone | |||||||

| * Human cortical | 131–224 | 35–283 | 17–20 | 1.07–2.10 | NBR | none | Autograft and allograft used for defect filling, alveolar ridge augmentation, sinus |

| * Human cancellous | 5–10 | 1.5–38 | 0.05–0.1 | 0.5–3 | NBR | 0.5–1 | augmentation, dental ridge preservation [51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60] |

| B. Degradable | |||||||

| * Collagen | 0.5–1 | 50–150 | 0.002–5 | 3 | 2–4 | 1–4 | Carriers (sponges) for BMP [61,62,63], composite with HA [64], membranes for GBR [65,66], scaffolds [67] |

| * Chitosan | 1.7–3.4 | 35–75 | 2–18 | 1–2 | 4–6 | <3 | Scaffolds, microgranules, composite materials, VBA, membranes, xerogels [68,69,70,71,72] |

| * PGA | 340–920 | 55–80 | 5–7 | 15–20 | 3–4 | 1 | Internal fixation, graft material, scaffold, composite [73,74,75] |

| * PLLA | 80–500 | 45–70 | 2.7 | 5–10 | >24 | 3 | Carrier for BMP, scaffolds, composite with HA [76,77,78,79,80,81,82] |

| * D,L(PLA) | 15–25 | 90–103 | 1.9 | 3–10 | 12–16 | 4 | Fracture fixation, interference screws [83,84,85] |

| * L(PLA) | 20–30 | 100–150 | 2.7 | 5–10 | >24 | 3 | Fracture fixation, Interference screws, scaffolds, bone graft material [74,77,86,87,88,89] |

| * PLGA | 40–55 | 55–80 | 1.4–2.8 | 3–10 | 1–12 | 1 | Interference screws, microspheres and carriers for BMP, scaffolds, composite [90,91,92,93] |

| * PCL | 20–40 | 10–35 | 0.4–0.6 | 300–500 | >24 | >6 | Scaffolds and composites with HA fillers [94,95,96,97,98,99] |

| * Hydroxyapatite | 500–1000 | 40–200 | 80–110 | 0.5–1 | >24 | >12 | Scaffolds, composites, bone fillers (granules and blocks), pastes, vertebroplasty, drug delivery, coatings [100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111] |

| * TCP | 154 | 25–80 | 60–75 | 1–2 | >24 | 1–6 | Bone fillers, injectable pastes, cements [112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122] |

| * Brushite | 35–60 | 15–25 | 40–55 | 2–3 | >24 | 1–6 | Drug delivery, restoration of metaphyseal defects, ligament anchor, reinforcement of |

| * Monetite | 15–25 | 10–15 | 22–35 | 3–4 | 3–6 | 1–3 | Osteosynthesis screws, ridge preservation, vertical bone augmentation, defect filling, vertebroplasty [123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143] |

| * Magnesium | 65–1000 | 135–285 | 41–45 | 2–10 | 0.25 | <1 | Implants, osteosynthesis devices, plates, screws, ligatures, and wires [122,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158] |

| C. Non-Degradable | |||||||

| * Titanium alloy | 900 | 900–1000 | 110–127 | 10–15 | No | None | Implants, plates, screws, BMP carriers, orthognathic surgery, mid-facial fracture treatment [159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166] |

| * Stainless Steel | 500–1000 | 460–1700 | 180–205 | 10–40 | No | None | Implants, plates, mini–plates, screws [167,168,169,170] |

| * Bioglass | 40–60 | 120–250 | 35 | 0–1 | No | None | Bone defect fillers [171,172,173,174,175,176,177] |

2.1. Polymers

2.1.1. Natural Biodegradable Polymers

Collagen

Chitosan

2.1.2. Synthetic Biodegradable Polymers

Poly (Glycolic Acid)

Poly (Lactic Acid)

Poly (Lactide-co-glycolide)

Poly (ε-Caprolactone)

Benzyl Ester of Hyaluronic Acid

Poly-para-dioxanone

2.1.3. Polymer Based Composites

2.2. Bioceramics

2.2.1. Tricalcium Phosphate

2.2.2. Hydroxyapatite

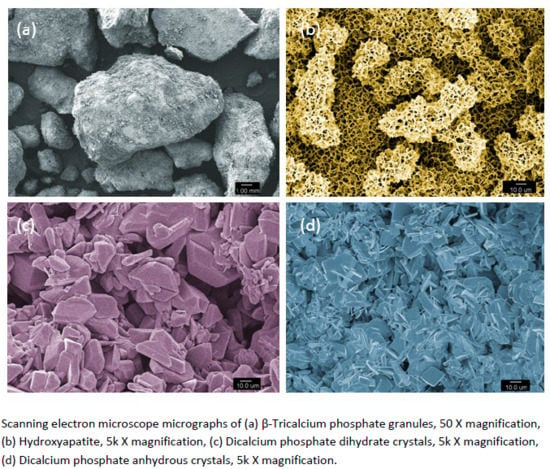

2.2.3. Dicalcium Phosphates

2.3. Magnesium Based Biodegradable Materials and Alloys

3. Biocompatibility of Implantable Materials and Their Degradation Products

4. Biodegradation of Implanted Materials and Bone Tissue Formation

5. Importance of Physical Properties and Geometrical Considerations of Biodegradable Scaffolds Used for Bone Tissue Engineering

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Driessens, F.C. Probable phase composition of the mineral in bone. Z. Naturfor. Sect. C 1980, 35, 357–362. [Google Scholar]

- Athanasiou, K.A.; Zhu, C.; Lanctot, D.R.; Agrawal, C.M.; Wang, X. Fundamentals of biomechanics in tissue engineering of bone. Tissue Eng. 2000, 6, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driessens, F.C.; van Dijk, J.W.; Borggreven, J.M. Biological calcium phosphates and their role in the physiology of bone and dental tissues I. Composition and solubility of calcium phosphates. Calcif. Tissue Res. 1978, 26, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaszemski, M.J.; Payne, R.G.; Hayes, W.C.; Langer, R.; Mikos, A.G. Evolution of bone transplantation: Molecular, cellular and tissue strategies to engineer human bone. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabie, A.B.; Wong, R.W.; Hagg, U. Composite autogenous bone and demineralized bone matrices used to repair defects in the parietal bone of rabbits. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2000, 38, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalcanti, S.C.; Pereira, C.L.; Mazzonetto, R.; de Moraes, M.; Moreira, R.W. Histological and histomorphometric analyses of calcium phosphate cement in rabbit calvaria. J. Cranio Maxillo Facial Surg. 2008, 36, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodrich, J.T.; Sandler, A.L.; Tepper, O. A review of reconstructive materials for use in craniofacial surgery bone fixation materials, bone substitutes, and distractors. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2012, 28, 1577–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, R.; Goldhahn, J.; Schwyn, R.; Regazzoni, P.; Suhm, N. Fixation principles in metaphyseal bone—A patent based review. Osteoporos. Int. 2005, 16, S54–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eglin, D.; Alini, M. Degradable polymeric materials for osteosynthesis: Tutorial. Eur. Cell Mater. 2008, 16, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Christensen, F.B.; Dalstra, M.; Sejling, F.; Overgaard, S.; Bunger, C. Titanium-alloy enhances bone-pedicle screw fixation: Mechanical and histomorphometrical results of titanium-alloy versus stainless steel. Eur. Spine J. 2000, 9, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eppley, B.L.; Sadove, A.M. A comparison of resorbable and metallic fixation in healing of calvarial bone grafts. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1995, 96, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marti, C.; Imhoff, A.B.; Bahrs, C.; Romero, J. Metallic versus bioabsorbable interference screw for fixation of bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft in arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A preliminary report. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 1997, 5, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, R.; Theodos, L. Fracture of the bone-grafted mandible secondary to stress shielding: Report of a case and review of the literature. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1993, 51, 695–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, D.R. Long-term implant fixation and stress-shielding in total hip replacement. J. Biomech. 2015, 48, 797–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanlalit, C.; Shukla, D.R.; Fitzsimmons, J.S.; An, K.N.; O’Driscoll, S.W. Stress shielding around radial head prostheses. J. Hand Surg. 2012, 37, 2118–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haase, K.; Rouhi, G. Prediction of stress shielding around an orthopedic screw: Using stress and strain energy density as mechanical stimuli. Comput. Biol. Med. 2013, 43, 1748–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabie, A.B.; Chay, S.H.; Wong, A.M. Healing of autogenous intramembranous bone in the presence and absence of homologous demineralized intramembranous bone. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2000, 117, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamradt, S.C.; Lieberman, J.R. Bone graft for revision hip arthroplasty: Biology and future applications. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2003, 417, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Urist, M.R. Bone transplants and implants. In Fundamental and Clinical Bone Physiology; MR, U., Ed.; JB Lippincott: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1980; pp. 331–368. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, V.M. Selection of bone grafts for revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2000, 381, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.H.; Samartzis, D.; An, H.S. Cell technologies for spinal fusion. Spine J. 2005, 5, 231S–239S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyne, P.J. Bone induction and the use of HTR polymer as a vehicle for osseous inductor materials. Compendium 1988, 10, S337–S341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Glowacki, J.; Mulliken, J.B. Demineralized bone implants. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1985, 12, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Banwart, J.C.; Asher, M.A.; Hassanein, R.S. Iliac crest bone graft harvest donor site morbidity. A statistical evaluation. Spine 1995, 20, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, N.; Tacconi, L.; Miles, J.B. Heterotopic bone formation causing recurrent donor site pain following iliac crest bone harvesting. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2000, 14, 476–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaggs, D.L.; Samuelson, M.A.; Hale, J.M.; Kay, R.M.; Tolo, V.T. Complications of posterior iliac crest bone grafting in spine surgery in children. Spine 2000, 25, 2400–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, B.N.; Eisenstein, S.M. Donor site pain from the ilium. A complication of lumbar spine fusion. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1989, 71, 677–680. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buck, B.E.; Malinin, T.I.; Brown, M.D. Bone transplantation and human immunodeficiency virus. An estimate of risk of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (aids). Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1989, 240, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shetty, V.; Han, T.J. Alloplastic materials in reconstructive periodontal surgery. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 1991, 35, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sabattini, V.B. Alloplastic implants (HA) for edentulous ridge augmentation before fixed dentures. Longitudinal reevaluation and histology. Prog. Odontoiatr. 1991, 4, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schaschke, C.; Audic, J.L. Editorial: Biodegradable materials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 21468–21475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, K.W.; Wong, K.H. Biodegradable metallic materials for orthopaedic implantations: A review. Technol. Health Care 2012, 20, 345–362. [Google Scholar]

- LeGeros, R.Z. Biodegradation and bioresorption of calcium phosphate ceramics. Clin. Mater. 1993, 14, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tevlin, R.; McArdle, A.; Atashroo, D.; Walmsley, G.G.; Senarath-Yapa, K.; Zielins, E.R.; Paik, K.J.; Longaker, M.T.; Wan, D.C. Biomaterials for craniofacial bone engineering. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freed, L.E.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G.; Biron, R.J.; Eagles, D.B.; Lesnoy, D.C.; Barlow, S.K.; Langer, R. Biodegradable polymer scaffolds for tissue engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. 1994, 12, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, L.G.; Naughton, G. Tissue engineering—Current challenges and expanding opportunities. Science 2002, 295, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burg, K.J.; Porter, S.; Kellam, J.F. Biomaterial developments for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 2347–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, Z.; Sima, C.; Glogauer, M. Bone replacement materials and techniques used for achieving vertical alveolar bone augmentation. Materials 2015, 8, 2953–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, Z.; Javaid, M.A.; Hamdan, N.; Hashmi, R. Bone regeneration using bone morphogenetic proteins and various biomaterial carriers. Materials 2015, 8, 1778–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, J.C.; Tipton, A.J. Synthetic biodegradable polymers as orthopedic devices. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 2335–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuisman, P.I.; Smit, T.H. Bioresorbable polymers: Heading for a new generation of spinal cages. Eur. Spine J. 2006, 15, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutmacher, D.; Hurzeler, M.B.; Schliephake, H. A review of material properties of biodegradable and bioresorbable polymers and devices for GTR and GBR applications. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 1996, 11, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ratner, B.D. Biomaterials Science: An introduction to Materials in Medicine. Academic Press: Waltham, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tamimi, F.; Sheikh, Z.; Barralet, J. Dicalcium phosphate cements: Brushite and monetite. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claes, L.E. Mechanical characterization of biodegradable implants. Clin. Mater. 1992, 10, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, J.; Hodgskinson, R.; Currey, J.D.; Mason, J.E. Mechanical properties of microcallus in human cancellous bone. J. Orthop. Res. 1992, 10, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.; Yu, X.; Wan, P.; Yang, K. Biodegradable materials for bone repairs: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2013, 29, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armentano, I.; Dottori, M.; Fortunati, E.; Mattioli, S.; Kenny, J. Biodegradable polymer matrix nanocomposites for tissue engineering: A review. Polymer Degrad. Stab. 2010, 95, 2126–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, F.; Hort, N.; Vogt, C.; Cohen, S.; Kainer, K.U.; Willumeit, R.; Feyerabend, F. Degradable biomaterials based on magnesium corrosion. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2008, 12, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoudis, P.V.; Dinopoulos, H.; Tsiridis, E. Bone substitutes: An update. Injury 2005, 36, S20–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury, F. Augmentation of the sinus floor with mandibular bone block and simultaneous implantation: A 6-year clinical investigation. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 1999, 14, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Block, M.S.; Degen, M. Horizontal ridge augmentation using human mineralized particulate bone: Preliminary results. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2004, 62, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolander, M.E.; Balian, G. The use of demineralized bone matrix in the repair of segmental defects. Augmentation with extracted matrix proteins and a comparison with autologous grafts. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1986, 68, 1264–1274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Araujo, P.P.; Oliveira, K.P.; Montenegro, S.C.; Carreiro, A.F.; Silva, J.S.; Germano, A.R. Block allograft for reconstruction of alveolar bone ridge in implantology: A systematic review. Implant Dent. 2013, 22, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterio, T.W.; Katancik, J.A.; Blanchard, S.B.; Xenoudi, P.; Mealey, B.L. A prospective, multicenter study of bovine pericardium membrane with cancellous particulate allograft for localized alveolar ridge augmentation. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2013, 33, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittaker, J.M.; James, R.A.; Lozada, J.; Cordova, C.; GaRey, D.J. Histological response and clinical evaluation of heterograft and allograft materials in the elevation of the maxillary sinus for the preparation of endosteal dental implant sites. Simultaneous sinus elevation and root form implantation: An eight-month autopsy report. J. Oral Implantol. 1989, 15, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valentini, P.; Abensur, D. Maxillary sinus floor elevation for implant placement with demineralized freeze-dried bone and bovine bone (bio-oss): A clinical study of 20 patients. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 1997, 17, 232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, J.S.; al-Jandan, B.A. Allograft for maxillary sinus floor augmentation: A retrospective study of 90 cases. Implant Dent. 2012, 21, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, G.; Neiva, R.; Misch, C.E.; Galindo-Moreno, P.; Benavides, E.; Rudek, I.; Wang, H.L. Clinical and histologic outcomes after the use of a novel allograft for maxillary sinus augmentation: A case series. Implant Dent. 2010, 19, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, D.S.; Lee, J.K.; An, K.M.; Shin, H.I. Histomorphometric evaluation of mineralized cancellous allograft in the maxillary sinus augmentation: A 4 case report. Implant Dent. 2009, 18, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, J.Y.; Jeong, S.I.; Shin, Y.M.; Kang, S.S.; Kim, S.E.; Jeong, C.M.; Huh, J.B. Sequential delivery of BMP-2 and BMP-7 for bone regeneration using a heparinized collagen membrane. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 4, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, J.K.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, S.H.; Cho, K.S.; Jung, U.W. Sinus augmentation using BMP-2 in a bovine hydroxyapatite/collagen carrier in dogs. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, M.; Li, R.; Friess, W. Collagen sponges for bone regeneration with rhbmp-2. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2003, 55, 1613–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, A.; Hong, L.; Ikada, Y.; Tabata, Y. A trial to prepare biodegradable collagen–hydroxyapatite composites for bone repair. J. Biomater. Sci. Polymer Ed. 2001, 12, 689–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.M.; Salkin, L.M.; Stein, M.D.; Freedman, A.L. Clinical evaluation of a biodegradable collagen membrane in guided tissue regeneration. J. Periodontol. 1990, 61, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matilinna, K.P. (Ed.) Barrier membranes for tissue regeneration and bone augmentation techniques in dentistry. In Handbook of Oral Biomaterials; Matilinna, K.P. (Ed.) Pan Stanford Publishing: Singapore, Singapore, 2014.

- Liu, X.; Ma, P.X. Polymeric scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2004, 32, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, G.; Ducheyne, P.; Reis, R. Materials in particulate form for tissue engineering. 1. Basic concepts. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2007, 1, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Shin, S.Y.; Rhyu, I.C.; Lee, Y.M.; Park, Y.J.; Chung, C.P.; Lee, S.J. Enhanced bone formation by transforming growth factor-β1-releasing collagen/chitosan microgranules. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2006, 76, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Ma, L.; Gao, C.; Shen, J. Fabrication and properties of mineralized collagen-chitosan/hydroxyapatite scaffolds. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2008, 19, 1590–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Jun, S.H.; Kim, H.E.; Kim, H.W.; Koh, Y.H.; Jang, J.H. Silica xerogel-chitosan nano-hybrids for use as drug eluting bone replacement. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2010, 21, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrose, C.G.; Hartline, B.E.; Clanton, T.O.; Lowe, W.R.; McGarvey, W.C. Polymers in orthopaedic surgery. In Advanced Polymers in Medicine; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Törmälä, P. Biodegradable self-reinforced composite materials; manufacturing structure and mechanical properties. Clin. Mater. 1992, 10, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christel, P.; Chabot, F.; Leray, J.; Morin, C.; Vert, M. Biodegradable composites for internal fixation. Biomaterials 1980, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Linhart, W.; Peters, F.; Lehmann, W.; Schwarz, K.; Schilling, A.F.; Amling, M.; Rueger, J.M.; Epple, M. Biologically and chemically optimized composites of carbonated apatite and polyglycolide as bone substitution materials. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001, 54, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Feng, Q.; Wang, M.; Guo, X.; Zheng, Q. Porous nano-HA/collagen/PLLA scaffold containing chitosan microspheres for controlled delivery of synthetic peptide derived from BMP-2. J. Controll. Release 2009, 134, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Z.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, R.; Sun, L. Fabrication of porous poly (l-lactic acid) scaffolds for bone tissue engineering via precise extrusion. Scr. Mater. 2001, 45, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, S.; Yamamuro, T.; Nakamura, T.; Ikada, Y.; Hyon, S.-H.; Jamshidi, K. Polymer-hydroxyapatite composites for biodegradable bone fillers. Biomaterials 1986, 7, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, S.I.A.; Sharif, N.; Rahman, W. Biodegradable polymers and their bone applications: A review. Int. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2012, 12, 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Vert, M. Aliphatic polyesters: Great degradable polymers that cannot do everything. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nejati, E.; Mirzadeh, H.; Zandi, M. Synthesis and characterization of nano-hydroxyapatite rods/poly (l-lactide acid) composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Compos. A 2008, 39, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagoa, A.L.; Wedemeyer, C.; von Knoch, M.; Löer, F.; Epple, M. A strut graft substitute consisting of a metal core and a polymer surface. J. Mater. Sci. 2008, 19, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warden, W.H.; Friedman, R.; Teresi, L.M.; Jackson, D.W. Magnetic resonance imaging of bioabsorbable polylactic acid interference screws during the first 2 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 1999, 15, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozic, K.J.; Perez, L.E.; Wilson, D.R.; Fitzgibbons, P.G.; Jupiter, J.B. Mechanical testing of bioresorbable implants for use in metacarpal fracture fixation. J. Hand Surg. 2001, 26, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignatius, A.; Claes, L.E. In vitro biocompatibility of bioresorbable polymers: Poly (l, dl-lactide) and poly (l-lactide-co-glycolide). Biomaterials 1996, 17, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenslag, J.W.; Pennings, A.J.; Bos, R.R.; Rozema, F.R.; Boering, G. Resorbable materials of poly (l-lactide): VII. In vivo and in vitro degradation. Biomaterials 1987, 8, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainionpää, S.; Kilpikari, J.; Laiho, J.; Helevirta, P.; Rokkanen, P.; Törmälä, P. Strength and strength retention vitro, of absorbable, self-reinforced polyglycolide (PGA) rods for fracture fixation. Biomaterials 1987, 8, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y.S.; Park, T.G. Porous biodegradable polymeric scaffolds prepared by thermally induced phase separation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1999, 47, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Chen, D.; Fu, J.; Yang, S.; Hou, R.; Suo, J. Macroporous biphasic calcium phosphate scaffolds reinforced by poly-l-lactic acid/hydroxyapatite nanocomposite coatings for bone regeneration. Biochem. Eng. J. 2015, 98, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Xu, G.P.; Zhang, Z.P.; Xia, J.J.; Yan, J.L.; Pan, S.H. BMP-2/PLGA delayed-release microspheres composite graft, selection of bone particulate diameters, and prevention of aseptic inflammation for bone tissue engineering. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 38, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavenis, K.; Schneider, U.; Groll, J.; Schmidt-Rohlfing, B. Bmp-7-loaded PGLA microspheres as a new delivery system for the cultivation of human chondrocytes in a collagen type I gel: The common nude mouse model. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2010, 33, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fei, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wu, D.; Wu, H.; Lu, R.; Bai, J.; Song, H. Preparation and property of a novel bone graft composite consisting of rhbmp-2 loaded PLGA microspheres and calcium phosphate cement. J. Mater. Sci. 2008, 19, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, F.A.; Ju, H.W.; Moon, B.M.; Lee, O.J.; Kim, J.H.; Park, H.J.; Kim, D.W.; Kim, D.K.; Jang, J.E.; Khang, G. Hybrid scaffolds based on PLGA and silk for bone tissue engineering. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Sun, K. Poly (ε-caprolactone)/hydroxyapatite composites: Effects of particle size, molecular weight distribution and irradiation on interfacial interaction and properties. Polymer Test. 2005, 24, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiria, F.; Leong, K.; Chua, C.; Liu, Y. Poly-ε-caprolactone/hydroxyapatite for tissue engineering scaffold fabrication via selective laser sintering. Acta Biomater. 2007, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Matthew, H.W.; Wooley, P.H.; Yang, S.Y. Effect of porosity and pore size on microstructures and mechanical properties of poly-ε-caprolactone-hydroxyapatite composites. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B 2008, 86, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, J.R.; Henson, A.; Popat, K.C. Biodegradable poly (ɛ-caprolactone) nanowires for bone tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, G.; Gratzl, M.; Kimmel, G.; Surles, J.; Sohindler, A. Aliphatic polyesters II. The degradation of poly (d,l-lactide), poly (ε-caprolactone), and their copolymers in vivo. Biomaterials 1981, 2, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosecká, E.; Rampichová, M.; Litvinec, A.; Tonar, Z.; Králíčková, M.; Vojtová, L.; Kochová, P.; Plencner, M.; Buzgo, M.; Míčková, A. Collagen/hydroxyapatite scaffold enriched with polycaprolactone nanofibers, thrombocyte-rich solution and mesenchymal stem cells promotes regeneration in large bone defect in vivo. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2015, 103, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balçik, C.; Tokdemir, T.; Şenköylü, A.; Koç, N.; Timuçin, M.; Akin, S.; Korkusuz, P.; Korkusuz, F. Early weight bearing of porous HA/TCP (60/40) ceramics in vivo: A longitudinal study in a segmental bone defect model of rabbit. Acta Biomater. 2007, 3, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quarto, R.; Mastrogiacomo, M.; Cancedda, R.; Kutepov, S.M.; Mukhachev, V.; Lavroukov, A.; Kon, E.; Marcacci, M. Repair of large bone defects with the use of autologous bone marrow stromal cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardziah, C.; Sopyan, I.; Ramesh, S. Strontium-doped hydroxyapatite nanopowder via sol-gel method: Effect of strontium concentration and calcination temperature on phase behavior. Trends Biomater. Artif. Organs 2009, 23, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Thian, E.; Huang, J.; Best, S.; Barber, Z.; Bonfield, W. Novel silicon-doped hydroxyapatite (Si-HA) for biomedical coatings: An in vitro study using acellular simulated body fluid. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B 2006, 76, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noshi, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Ikeuchi, M.; Dohi, Y.; Ohgushi, H.; Horiuchi, K.; Sugimura, M.; Ichijima, K.; Yonemasu, K. Enhancement of the in vivo osteogenic potential of marrow/hydroxyapatite composites by bovine bone morphogenetic protein. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 52, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonishi, H. Orthopaedic applications of hydroxyapatite. Biomaterials 1991, 12, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.D.; Thomas, K.A.; Kay, J.F.; Jarcho, M. Hydroxyapatite-coated titanium for orthopedic implant applications. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1988, 232, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sopyan, I.; Mel, M.; Ramesh, S.; Khalid, K. Porous hydroxyapatite for artificial bone applications. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2007, 8, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, U.; Osborn, J.; Duwe, F. Hydroxyapatite ceramic as a bone substitute. Int. Orthop. 1990, 14, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Biswas, K.; Basu, B. Hydroxyapatite-titanium bulk composites for bone tissue engineering applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2015, 103, 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumic-Cule, I.; Pecina, M.; Jelic, M.; Jankolija, M.; Popek, I.; Grgurevic, L.; Vukicevic, S. Biological aspects of segmental bone defects management. Int. Orthop. 2015, 39, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.B.; Majumdar, S. The composite of hydroxyapatite with collagen as a bone grafting material. J. Adv. Med. Dent. Sci. Res. 2014, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hing, K.A.; Wilson, L.F.; Buckland, T. Comparative performance of three ceramic bone graft substitutes. Spine J. 2007, 7, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandi, S.K.; Ghosh, S.K.; Kundu, B.; De, D.K.; Basu, D. Evaluation of new porous β-tri-calcium phosphate ceramic as bone substitute in goat model. Small Rumin. Res. 2008, 75, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Nandi, S.K.; Kundu, B.; Datta, S.; De, D.K.; Roy, S.K.; Basu, D. In vivo response of porous hydroxyapatite and β-tricalcium phosphate prepared by aqueous solution combustion method and comparison with bioglass scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B 2008, 86, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutright, D.E.; Bhaskar, S.N.; Brady, J.M.; Getter, L.; Posey, W.R. Reaction of bone to tricalcium phosphate ceramic pellets. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1972, 33, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohner, M. Physical and chemical aspects of calcium phosphates used in spinal surgery. Eur. Spine J. 2001, 10, S114–S121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peter, S.J.; Kim, P.; Yasko, A.W.; Yaszemski, M.J.; Mikos, A.G. Crosslinking Characteristics of an Injectable Poly (Propylene Fumarate)/β-tricalcium Phosphate Paste and Mechanical Properties of the Crosslinked Composite for Use as a Biodegradable Bone Cement; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, P.; Saiz, E.; Gryn, K.; Tomsia, A.P. Sintering and robocasting of β-tricalcium phosphate scaffolds for orthopaedic applications. Acta Biomater. 2006, 2, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galois, L.; Mainard, D.; Delagoutte, J. Beta-tricalcium phosphate ceramic as a bone substitute in orthopaedic surgery. Int. Orthop. 2002, 26, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Meng, S.; Huang, Y.; Xu, M.; He, Y.; Lin, H.; Han, J.; Chai, Y.; Wei, Y.; Deng, X. Electrospun gelatin/β-TCP composite nanofibers enhance osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and in vivo bone formation by activating Ca2+. Stem Cells Int. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Lun, D.X. Current application of β-tricalcium phosphate composites in orthopaedics. Orthop. Surg. 2012, 4, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadanbaz, S.; Dias, G.J. Calcium phosphate coatings on magnesium alloys for biomedical applications: A review. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamimi, F.; Kumarasami, B.; Doillon, C.; Gbureck, U.; le Nihouannen, D.; Cabarcos, E.L.; Barralet, J.E. Brushite-collagen composites for bone regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2008, 4, 1315–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamimi, F.; Torres, J.; al-Abedalla, K.; Lopez-Cabarcos, E.; Alkhraisat, M.H.; Bassett, D.C.; Gbureck, U.; Barralet, J.E. Osseointegration of dental implants in 3D-printed synthetic onlay grafts customized according to bone metabolic activity in recipient site. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 5436–5445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamimi, F.; Torres, J.; Bassett, D.; Barralet, J.; Cabarcos, E.L. Resorption of monetite granules in alveolar bone defects in human patients. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 2762–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamimi, F.; Torres, J.; Bettini, R.; Ruggera, F.; Rueda, C.; Lopez-Ponce, M.; Lopez-Cabarcos, E. Doxycycline sustained release from brushite cements for the treatment of periodontal diseases. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2008, 85, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamimi, F.; Torres, J.; Gbureck, U.; Lopez-Cabarcos, E.; Bassett, D.C.; Alkhraisat, M.H.; Barralet, J.E. Craniofacial vertical bone augmentation: A comparison between 3D printed monolithic monetite blocks and autologous onlay grafts in the rabbit. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6318–6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tamimi, F.; Torres, J.; Lopez-Cabarcos, E.; Bassett, D.C.; Habibovic, P.; Luceron, E.; Barralet, J.E. Minimally invasive maxillofacial vertical bone augmentation using brushite based cements. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Sato, S.; Kishida, M.; Asano, S.; Murai, M.; Ito, K. The use of porous beta-tricalcium phosphate blocks with platelet-rich plasma as an onlay bone graft biomaterial. J. Periodontol. 2007, 78, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinno, F.T.; Torres, J.; Tresguerres, I.; Jerez, L.B.; Cabarcos, E.L. Vertical bone augmentation with granulated brushite cement set in glycolic acid. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2007, 81, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Landuyt, P.; Peter, B.; Beluze, L.; Lemaitre, J. Reinforcement of osteosynthesis screws with brushite cement. Bone 1999, 25, 95S–98S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrke SA, F.G. Buccal dehiscence and sinus lift cases—Predictable bone augmentation with synthetic bone material. Implants 2010, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, J.Z.; Donnelly, K.; Keatch, R.P.; Baar, K.; Grover, L.M. Factors affecting the longevity and strength in an in vitro model of the bone-ligament interface. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 38, 2155–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paxton, J.Z.; Grover, L.M.; Baar, K. Engineering an in vitro model of a functional ligament from bone to bone. Tissue Eng. Part A 2010, 16, 3515–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrban, N.; Paxton, J.Z.; Bowen, J.; Bolarinwa, A.; Vorndran, E.; Gbureck, U.; Grover, L.M. Comparing physicochemical properties of printed and hand cast biocements designed for ligament replacement. Adv. Appl. Ceram. 2011, 110, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theiss, F.; Apelt, D.; Brand, B.; Kutter, A.; Zlinszky, K.; Bohner, M.; Matter, S.; Frei, C.; Auer, J.A.; von Rechenberg, B. Biocompatibility and resorption of a brushite calcium phosphate cement. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 4383–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Luchini, T.J.; Agarwal, A.K.; Goel, V.K.; Bhaduri, S.B. Development of monetite-nanosilica bone cement: A preliminary study. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B 2014, 102, 1620–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saska, S.; Mendes, L.S.; Gaspar, A.M.M.; de Oliveira Capote, T.S. Bone substitute materials in implant dentistry. Implant Dent. 2015, 2, 158–167. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, E.; Yanni, T.; Jamshidi, P.; Grover, L. Inorganic cements for biomedical application: Calcium phosphate, calcium sulphate and calcium silicate. Adv. Appl. Ceram. 2015, 114, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestres, G.; Santos, C.F.; Engman, L.; Persson, C.; Ott, M.K. Scavenging effect of trolox released from brushite cements. Acta Biomater. 2015, 11, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, L.C.; Chari, J.; Aghyarian, S.; Gindri, I.M.; Kosmopoulos, V.; Rodrigues, D.C. Preparation and characterization of injectable brushite filled-poly (methyl methacrylate) bone cement. Materials 2014, 7, 6779–6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wan, W.; Xu, K.; Yuan, Q.; Xing, M. Dual-functional biomaterials for bone regeneration and infection control. J. Biomater. Tissue Eng. 2014, 4, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, J.P.; Carroll, M.E.; Mccanless, J.D. Composite Bone Graft Substitute Cement and Articles Produced Therefrom. U.S. Patent 7,754,246, 13 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Staiger, M.P.; Pietak, A.M.; Huadmai, J.; Dias, G. Magnesium and its alloys as orthopedic biomaterials: A review. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 1728–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, H.M.; Yeung, K.W.; Lam, K.O.; Tam, V.; Chu, P.K.; Luk, K.D.; Cheung, K.M. A biodegradable polymer-based coating to control the performance of magnesium alloy orthopaedic implants. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 2084–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zeng, R.; Dietzel, W.; Witte, F.; Hort, N.; Blawert, C. Progress and challenge for magnesium alloys as biomaterials. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2008, 10, B3–B14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waizy, H.; Seitz, J.-M.; Reifenrath, J.; Weizbauer, A.; Bach, F.-W.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Denkena, B.; Windhagen, H. Biodegradable magnesium implants for orthopedic applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.-N.; Zheng, Y.-F. A review on magnesium alloys as biodegradable materials. Front. Mater. Sci. China 2010, 4, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, F. The history of biodegradable magnesium implants: A review. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 1680–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wan, P.; Tan, L.L.; Wang, K.; Yang, K. Preclinical investigation of an innovative magnesium-based bone graft substitute for potential orthopaedic applications. J. Orthop. Transl. 2014, 2, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyndon, J.A.; Boyd, B.J.; Birbilis, N. Metallic implant drug/device combinations for controlled drug release in orthopaedic applications. J. Controll. Release 2014, 179, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaya, A.; Yoshizawa, S.; Verdelis, K.; Myers, N.; Costello, B.J.; Chou, D.-T.; Pal, S.; Maiti, S.; Kumta, P.N.; Sfeir, C. In vivo study of magnesium plate and screw degradation and bone fracture healing. Acta Biomater. 2015, 18, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, G.; Li, Q.; Wang, C.; Dong, J.; He, G. Fabrication of graded porous titanium–magnesium composite for load-bearing biomedical applications. Mater. Des. 2015, 67, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.-S. Investigation on Mg-Mn-Zn Alloys as Potential Biodegradable Materials for Orthopaedic Applications; The University of Hong Kong: Pokfulam, Hong Kong, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chaya, A.; Yoshizawa, S.; Verdelis, K.; Noorani, S.; Costello, B.J.; Sfeir, C. Fracture healing using degradable magnesium fixation plates and screws. J. Oral Maxil. Surg. 2015, 73, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Huang, W.; Li, Q.; She, Z.; Chen, F.; Li, L. A novel multilayer model with controllable mechanical properties for magnesium-based bone plates. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khakbaz, H.; Walter, R.; Gordon, T.; Kannan, M.B. Self-dissolution assisted coating on magnesium metal for biodegradable bone fixation devices. Mater. Res. Express 2014, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, J.; Xie, X.; Zhang, P.; Lai, Y.; Li, Y.; Qin, L. Surface coating reduces degradation rate of magnesium alloy developed for orthopaedic applications. J. Orthop. Transl. 2013, 1, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Stok, J.; Koolen, M.; de Maat, M.; Yavari, S.A.; Alblas, J.; Patka, P.; Verhaar, J.; van Lieshout, E.; Zadpoor, A.; Weinans, H. Full regeneration of segmental bone defects using porous titanium implants loaded with BMP-2 containing fibrin gels. Eur. Cells Mater. 2015, 29, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Mikos, A.G.; Wong, M.E.; Young, S.W.; Kretlow, J.D.; Shi, M.; Kasper, K.F.; Spicer, P. Combined Space Maintenance and Bone Regeneration System for the Reconstruction of Large Osseous Defects. US Patent 20,150,081,034, 19 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, A.; Comerford, E.; Birch, R.; Innes, J.; Walton, M. Mechanical performance in axial compression of a titanium polyaxial locking plate system in a fracture gap model. Vet. Comp. Orthop. Traumatol. 2015, 28, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Moraissi, E.A.M.; Ellis, E. Biodegradable and titanium osteosynthesis provide similar stability for orthognathic surgery. J. Oral. Maxil. Surg. 2015, 73, 1795–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, I.G.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, S.T.; Choi, J.Y.; Sykes, J.M. Comparison of titanium and biodegradable plates for treating midfacial fractures. J. Oral. Maxil. Surg. 2014, 72, 761–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzoni, S.; Bianchi, A.; Schiariti, G.; Badiali, G.; Marchetti, C. Cad-cam cutting guides and customized titanium plates useful in upper maxilla waferless repositioning. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 201 2015, 73, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paeng, J.-Y.; Hong, J.; Kim, C.-S.; Kim, M.-J. Comparative study of skeletal stability between bicortical resorbable and titanium screw fixation after sagittal split ramus osteotomy for mandibular prognathism. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 40, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buijs, G.; van Bakelen, N.; Jansma, J.; de Visscher, J.; Hoppenreijs, T.; Bergsma, J.; Stegenga, B.; Bos, R. A randomized clinical trial of biodegradable and titanium fixation systems in maxillofacial surgery. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Bansal, V.; Kumar, S.; Mowar, A. Comparative analysis of osteosynthesis of mandibular anterior fractures following open reduction using “stainless steel lag screws and mini plates”. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2013, 12, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, S.; Chalivendra, V.; Rahbar, N.; el Wakil, S. Mechanical characterization and modeling of graded porous stainless steel specimens for possible bone implant applications. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2012, 53, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, K.K.; Hussein, S.Z.S.; Ahmad, A.L.; McPhail, D.S.; Boccaccini, A.R. Corrosion resistance study of electrophoretic deposited hydroxyapatite on stainless steel for implant applications. Key Eng. Mater. 2012, 507, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivic, F.; Babic, M.; Grujovic, N.; Mitrovic, S.; Adamovic, D. Influence of loose PMMA bone cement particles on the corrosion assisted wear of the orthopedic AISI 316LVM stainless steel during reciprocating sliding. Wear 2013, 300, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallittu, P.K.; Närhi, T.O.; Hupa, L. Fiber glass–bioactive glass composite for bone replacing and bone anchoring implants. Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamuro, T. Clinical applications of bioactive glass-ceramics. New Mater. Technol. Healthc. 2012, 1, 1–97. [Google Scholar]

- Rahaman, M.N.; Liu, X.; Bal, B.S.; Day, D.E.; Bi, L.; Bonewald, L.F. Bioactive glass in bone tissue engineering. Biomater. Sci. 2012, 237, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hench, L.L. Chronology of bioactive glass development and clinical applications. Sci. Res. 2013, 3, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balani, K.; Narayan, R.; Agarwal, A.; Verma, V. Surface engineering and modification for biomedical applications. Biosurfaces 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorilli, S.; Baino, F.; Cauda, V.; Crepaldi, M.; Vitale-Brovarone, C.; Demarchi, D.; Onida, B. Electrophoretic deposition of mesoporous bioactive glass on glass–ceramic foam scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheri, Z.S.; Giles, E.; El Sawi, I.; Amleh, A.; Schemitsch, E.H.; Zdero, R.; Bougherara, H. Osteogenesis and cytotoxicity of a new carbon fiber/flax/epoxy composite material for bone fracture plate applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 46, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzak, W.S.; Sarver, D.R.; Verstynen, M.L. Bioabsorbable polymer science for the practicing surgeon. J. Craniofac. Surg 1997, 8, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.A.; Brady, J.M.; Cutright, D.E. Degradation rates of oral resorbable implants (polylactates and polyglycolates): Rate modification with changes in PLA/PGA copolymer ratios. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1977, 11, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertesteanu, S.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Printza, A.G.; Marie-Paule, T.; Grumezescu, V.; Mihaela, V.; Lazar, V.; Grigore, R. Biomedical applications of synthetic, biodegradable polymers for the development of anti-infective strategies. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 3383–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulery, B.D.; Nair, L.S.; Laurencin, C.T. Biomedical applications of biodegradable polymers. J. Polymer Sci. Part B Polymer Phys. 2011, 49, 832–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Garreau, H.; Vert, M. Structure-property relationships in the case of the degradation of massive poly (α-hydroxy acids) in aqueous media. J. Mater. Sci. 1990, 1, 198–206. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, A.W. Interfacial bioengineering to enhance surface biocompatibility. Med. Device Technol. 2001, 13, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Domb, A.J.; Kost, J.; Wiseman, D. Handbook of Biodegradable Polymers; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby, S.W.; Burg, K.J. Absorbable and Biodegradable Polymers; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pachence, J.M.; Kohn, J. Biodegradable polymers. Princ. Tissue Eng. 2000, 3, 323–339. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, L.S.; Laurencin, C.T. Biodegradable polymers as biomaterials. Prog. Polymer Sci. 2007, 32, 762–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, G.H.; Diaz, F.; Jakuba, C.; Calabro, T.; Horan, R.L.; Chen, J.; Lu, H.; Richmond, J.; Kaplan, D.L. Silk-based biomaterials. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachence, J.; Berg, R.; Silver, F. Collagen: Its place in the medical device industry. Med. Device Diagn. Ind. 1987, 9, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chevallay, B.; Herbage, D. Collagen-based biomaterials as 3d scaffold for cell cultures: Applications for tissue engineering and gene therapy. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2000, 38, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddi, A.H. Role of morphogenetic proteins in skeletal tissue engineering and regeneration. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998, 16, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Chen, X.; Zhao, N. Biomimetic formation of hydroxyapatite/collagen matrix composite. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2006, 8, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roveri, N.; Falini, G.; Sidoti, M.; Tampieri, A.; Landi, E.; Sandri, M.; Parma, B. Biologically inspired growth of hydroxyapatite nanocrystals inside self-assembled collagen fibers. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2003, 23, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liao, S.; Cui, F. Hierarchical self-assembly of nano-fibrils in mineralized collagen. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 3221–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, M.; Itoh, S.; Ichinose, S.; Shinomiya, K.; Tanaka, J. Self-organization mechanism in a bone-like hydroxyapatite/collagen nanocomposite synthesized in vitro and its biological reaction in vivo. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 1705–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.H.; Lee, J.D.; Tanaka, J. Nucleation of hydroxyapatite crystal through chemical interaction with collagen. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2000, 83, 2890–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, F.Y.; Chueh, S.-C.; Wang, Y.J. Microspheres of hydroxyapatite/reconstituted collagen as supports for osteoblast cell growth. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 1931–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, J.; Goldie, E.; Connel, G.; Merry, J.; Grant, M. Osteoblast interactions with calcium phosphate ceramics modified by coating with type I collagen. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2005, 73, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.; Serricella, P.; Linhares, A.; Guerdes, R.; Borojevic, R.; Rossi, M.; Duarte, M.; Farina, M. Characterization of a bovine collagen-hydroxyapatite composite scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 4987–4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Weng, W.; Deng, X.; Cheng, K.; Liu, X.; Du, P.; Shen, G.; Han, G. Preparation and characterization of porous beta-tricalcium phosphate/collagen composites with an integrated structure. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 5276–5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneiders, W.; Reinstorf, A.; Pompe, W.; Grass, R.; Biewener, A.; Holch, M.; Zwipp, H.; Rammelt, S. Effect of modification of hydroxyapatite/collagen composites with sodium citrate, phosphoserine, phosphoserine/rgd-peptide and calcium carbonate on bone remodelling. Bone 2007, 40, 1048–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marouf, H.A.; Quayle, A.A.; Sloan, P. In vitro and in vivo studies with collagen/hydroxyapatite implants. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 1989, 5, 148–154. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, W.E. A new calcium phosphate, water-setting cement. Cements Res. Prog. 1987, 351–379. [Google Scholar]

- Barralet, J.; Grover, L.; Gbureck, U. Ionic modification of calcium phosphate cement viscosity. Part II: Hypodermic injection and strength improvement of brushite cement. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 2197–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.N.R. A review of chitin and chitosan applications. React. Funct. Polymers 2000, 46, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madihally, S.V.; Matthew, H.W. Porous chitosan scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, K.A.; Shah, A.R.; Hernandez, R.J.; LeBaron, R.G. Basic science of articular cartilage repair. Clin. Sports Med. 2001, 20, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornish, M.; Kaplan, D.; Skaugrud, Ø. Standards and guidelines for biopolymers in tissue-engineered medical products. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2001, 944, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhu, Y.; Ran, X.; Wang, M.; Su, Y.; Cheng, T. Therapeutic potential of chitosan and its derivatives in regenerative medicine. J. Surg. Res. 2006, 133, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeherman, H.; Li, R.; Wozney, J. A review of preclinical program development for evaluating injectable carriers for osteogenic factors. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2003, 85, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chesnutt, B.M.; Viano, A.M.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Guda, T.; Appleford, M.R.; Ong, J.L.; Haggard, W.O.; Bumgardner, J.D. Design and characterization of a novel chitosan/nanocrystalline calcium phosphate composite scaffold for bone regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2009, 88, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.-J.; Shin, D.-S.; Kim, H.-E.; Kim, H.-W.; Koh, Y.-H.; Jang, J.-H. Membrane of hybrid chitosan–silica xerogel for guided bone regeneration. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Qian, J.; Wang, J.; Yao, W.; Liu, C.; Chen, J.; Cao, X. Enhanced bioactivity of bone morphogenetic protein-2 with low dose of 2-n, 6-o-sulfated chitosan in vitro and in vivo. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 1715–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vert, M.; Li, S.; Spenlehauer, G.; Guérin, P. Bioresorbability and biocompatibility of aliphatic polyesters. J. Mater. Sci. 1992, 3, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seal, B.; Otero, T.; Panitch, A. Polymeric biomaterials for tissue and organ regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2001, 34, 147–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, J.F.; Sousa, R.A.; Boesel, L.F.; Neves, N.M.; Reis, R.L. Bioinert, biodegradable and injectable polymeric matrix composites for hard tissue replacement: State of the art and recent developments. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2004, 64, 789–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohn, J. Bioresorbable and Bioerodible Materials. In Biomaterials Science: An Introduction to Materials in Medicine; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jagur-Grodzinski, J. Biomedical application of functional polymers. React. Funct. Polymers 1999, 39, 99–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, L. Polymeric biomaterials. Acta Mater. 2000, 48, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezwan, K.; Chen, Q.; Blaker, J.; Boccaccini, A.R. Biodegradable and bioactive porous polymer/inorganic composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 3413–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godbey, W.; Atala, A. In vitro systems for tissue engineering. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2002, 961, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmus, M.N.; Hubbell, J.A. Materials selection. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 1993, 2, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, R.; Moore, E.; Hegyeli, A.; Leonard, F. Biodegradable poly (lactic acid) polymers. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1971, 5, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, P.X.; Zhang, R.; Xiao, G.; Franceschi, R. Engineering new bone tissue in vitro on highly porous poly (α-hydroxyl acids)/hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001, 54, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vert, M.; Mauduit, J.; Li, S. Biodegradation of PLA/GA polymers: Increasing complexity. Biomaterials 1994, 15, 1209–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winet, H.; Bao, J. Comparative bone healing near eroding polylactide-polyglycolide implants of differing crystallinity in rabbit tibial bone chambers. J. Biomater. Sci. Polymer Ed. 1997, 8, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Winet, H.; Bao, J. Acidity near eroding polylactide-polyglycolide in vitro and in vivo in rabbit tibial bone chambers. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 2373–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, C.M.; Athanasiou, K.A. Technique to control pH in vicinity of biodegrading PLA-PGA implants. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1997, 38, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.; Gilding, D. Biodegradable polymers for use in surgery—poly (glycolic)/poly (iactic acid) homo and copolymers: 2. In vitro degradation. Polymer 1981, 22, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikada, Y.; Tsuji, H. Biodegradable polyesters for medical and ecological applications. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2000, 21, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, K.A.; Niederauer, G.G.; Agrawal, C.M. Sterilization, toxicity, biocompatibility and clinical applications of polylactic acid/polyglycolic acid copolymers. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVicar, I.; Hatton, P.; Brook, I. Self-reinforced polyglycolic acid membrane: A bioresorbable material for orbital floor repair. Initial clinical report. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1995, 33, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurus, P.B.; Kaeding, C.C. Bioabsorbable implant material review. Oper. Tech. Sports Med. 2004, 12, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törmälä, P.; Vasenius, J.; Vainionpää, S.; Laiho, J.; Pohjonen, T.; Rokkanen, P. Ultra-high-strength absorbable self-reinforced polyglycolide (SR-PGA) composite rods for internal fixation of bone fractures: In vitro and in vivo study. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1991, 25, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutright, D.E.; Perez, B.; Beasley, J.D.; Larson, W.J.; Posey, W.R. Degradation rates of polymers and copolymers of polylactic and polyglycolic acids. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1974, 37, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, R.; Henry, M. Lactic acid: Recent advances in products, processes and technologies—A review. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2006, 81, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlotta, D. A literature review of poly (lactic acid). J. Polym. Environ. 2001, 9, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argarate, N.; Olalde, B.; Atorrasagasti, G.; Valero, J.; Cifuentes, S.C.; Benavente, R.; Lieblich, M.; González-Carrasco, J.L. Biodegradable bi-layered coating on polymeric orthopaedic implants for controlled release of drugs. Mater. Lett. 2014, 132, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H.; Ikada, Y. Blends of aliphatic polyesters. Ii. Hydrolysis of solution-cast blends from poly (l-lactide) and poly (e-caprolactone) in phosphate-buffered solution. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1998, 67, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, R. The case for polylactic acid as a commodity packaging plastic. J. Macromol. Sci. A 1996, 33, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawai, D.; Takahashi, K.; Imamura, T.; Nakamura, K.; Kanamoto, T.; Hyon, S.H. Preparation of oriented β-form poly (l-lactic acid) by solid-state extrusion. J. Polym. Sci. B 2002, 40, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, T.; Doi, Y. Morphology and enzymatic degradation of poly (l-lactic acid) single crystals. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 2461–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urayama, H.; Kanamori, T.; Kimura, Y. Properties and biodegradability of polymer blends of poly (l-lactide) s with different optical purity of the lactate units. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2002, 287, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, S.R.; Hakkarainen, M.; Inkinen, S.; Södergård, A.; Albertsson, A.-C. Polylactide stereocomplexation leads to higher hydrolytic stability but more acidic hydrolysis product pattern. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabir, M.I.; Xu, X.; Li, L. A review on biodegradable polymeric materials for bone tissue engineering applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2009, 44, 5713–5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, J.K.; Riley, S.L.; Palazzolo, R.; Brown, S.C.; Monkhouse, D.C.; Coates, M.; Griffith, L.G.; Landeen, L.K.; Ratcliffe, A. A three-dimensional osteochondral composite scaffold for articular cartilage repair. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 4739–4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandfils, C.; Flandroy, P.; Nihant, N.; Barbette, S.; Jérôme, R.; Teyssié, P.; Thibaut, A. Preparation of poly (D, L) lactide microspheres by emulsion–solvent evaporation, and their clinical applications as a convenient embolic material. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1992, 26, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, I.; Robinson, B.P.; Hollinger, J.O.; Szachowicz, E.H.; Brekke, J. Calvarial bone repair with porous d, l-polylactide. Otolaryngology 1995, 112, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, M.; Shea, L.; Peters, M.; Mooney, D. Bioabsorbable polymer scaffolds for tissue engineering capable of sustained growth factor delivery. J. Controll. Release 2000, 64, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ma, P.X. Porous poly (l-lactic acid)/apatite composites created by biomimetic process. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1999, 45, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikos, A.G.; Thorsen, A.J.; Czerwonka, L.A.; Bao, Y.; Langer, R.; Winslow, D.N.; Vacanti, J.P. Preparation and characterization of poly (l-lactic acid) foams. Polymer 1994, 35, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schugens, C.; Maquet, V.; Grandfils, C.; Jérôme, R.; Teyssie, P. Polylactide macroporous biodegradable implants for cell transplantation. II. Preparation of polylactide foams by liquid-liquid phase separation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1996, 30, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Ma, P.X. Macroporous and nanofibrous polymer scaffolds and polymer/bone-like apatite composite scaffolds generated by sugar spheres. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2006, 78, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieu, L.M.; Mueller, T.L.; Bourban, P.-E.; Pioletti, D.P.; Müller, R.; Månson, J.-A.E. Architecture and properties of anisotropic polymer composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jie, W.; Yubao, L. Tissue engineering scaffold material of nano-apatite crystals and polyamide composite. Eur. Polym. J. 2004, 40, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, Y.; Lau, K.-T. Preparation and characterization of a nano apatite/polyamide 6 bioactive composite. Compos. B 2007, 38, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flahiff, C.M.; Blackwell, A.S.; Hollis, J.M.; Feldman, D.S. Analysis of a biodegradable composite for bone healing. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1996, 32, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramay, H.R.; Zhang, M. Biphasic calcium phosphate nanocomposite porous scaffolds for load-bearing bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 5171–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunatillake, P.; Mayadunne, R.; Adhikari, R. Recent developments in biodegradable synthetic polymers. Biotechnol. Annu. Rev. 2006, 12, 301–347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hollinger, J.O. Preliminary report on the osteogenic potential of a biodegradable copolymer of polyactide (PLA) and polyglycolide (PGA). J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1983, 17, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, J.F.; Stanford, H.G.; Cutright, D.E. Evaluation and comparisons of biodegradable substances as osteogenic agents. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1977, 43, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunatillake, P.A.; Adhikari, R. Biodegradable synthetic polymers for tissue engineering. Eur. Cell Mater. 2003, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; Khang, G.; Lee, Y.M.; Lee, H.B. Interaction of human chondrocytes and NIH/3T3 fibroblasts on chloric acid-treated biodegradable polymer surfaces. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2002, 13, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Södergård, A.; Stolt, M. Properties of lactic acid based polymers and their correlation with composition. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2002, 27, 1123–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, W.L.; Kohn, D.H.; Mooney, D.J. Growth of continuous bonelike mineral within porous poly (lactide-co-glycolide) scaffolds in vitro. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 50, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knepper-Nicolai, B.; Reinstorf, A.; Hofinger, I.; Flade, K.; Wenz, R.; Pompe, W. Influence of osteocalcin and collagen I on the mechanical and biological properties of biocement D. Biomol. Eng. 2002, 19, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, C.D.; Costantino, P.D.; Takagi, S.; Chow, L.C. Bonesource™ hydroxyapatite cement: A novel biomaterial for craniofacial skeletal tissue engineering and reconstruction. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1998, 43, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Best, S.; Bonfield, W.; Brooks, R.; Rushton, N.; Jayasinghe, S.; Edirisinghe, M. In vitro assessment of the biological response to nano-sized hydroxyapatite. J. Mater. Sci. 2004, 15, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzatini, S.; Solito, R.; Morbidelli, L.; Lamponi, S.; Boanini, E.; Bigi, A.; Ziche, M. The effect of hydroxyapatite nanocrystals on microvascular endothelial cell viability and functions. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2006, 76, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, B.; Wachtel, H.; Noppe, C. Patterns of mineralization in vitro. Cell Tissue Res. 1991, 263, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciapetti, G.; Ambrosio, L.; Savarino, L.; Granchi, D.; Cenni, E.; Baldini, N.; Pagani, S.; Guizzardi, S.; Causa, F.; Giunti, A. Osteoblast growth and function in porous poly ε-caprolactone matrices for bone repair: A preliminary study. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 3815–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Kurashina, K.; de Bruijn, J.D.; Li, Y.; de Groot, K.; Zhang, X. A preliminary study on osteoinduction of two kinds of calcium phosphate ceramics. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 1799–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuboki, Y.; Jin, Q.; Takita, H. Geometry of carriers controlling phenotypic expression in bmp-induced osteogenesis and chondrogenesis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2001, 83, S105–S115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tamai, N.; Myoui, A.; Hirao, M.; Kaito, T.; Ochi, T.; Tanaka, J.; Takaoka, K.; Yoshikawa, H. A new biotechnology for articular cartilage repair: Subchondral implantation of a composite of interconnected porous hydroxyapatite, synthetic polymer (PLA-PEG), and bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2). Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2005, 13, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Hong, Z.; Yu, T.; Chen, X.; Jing, X. In vivo mineralization and osteogenesis of nanocomposite scaffold of poly (lactide-co-glycolide) and hydroxyapatite surface-grafted with poly (l-lactide). Biomaterials 2009, 30, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labet, M.; Thielemans, W. Synthesis of polycaprolactone: A review. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 3484–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kweon, H.; Yoo, M.K.; Park, I.K.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, H.C.; Lee, H.-S.; Oh, J.-S.; Akaike, T.; Cho, C.-S. A novel degradable polycaprolactone networks for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelberg, I.; Kohn, J. Physico-mechanical properties of degradable polymers used in medical applications: A comparative study. Biomaterials 1991, 12, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, A.; Rizzi, S.; Williamson, M.; Barralet, J.; Downes, S.; Wallace, W. Precipitation casting of polycaprolactone for applications in tissue engineering and drug delivery. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, C.; Ray, R.B. Biodegradable polymeric scaffolds for musculoskeletal tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001, 55, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondrinos, M.J.; Dembzynski, R.; Lu, L.; Byrapogu, V.K.; Wootton, D.M.; Lelkes, P.I.; Zhou, J. Porogen-based solid freeform fabrication of polycaprolactone–calcium phosphate scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 4399–4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishna, S.; Mayer, J.; Wintermantel, E.; Leong, K.W. Biomedical applications of polymer-composite materials: A review. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2001, 61, 1189–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, L.; Cortivo, R.; Berti, T.; Berti, A.; Pea, F.; Mazzo, M.; Moras, M.; Abatangelo, G. Biocompatibility and biodegradation of different hyaluronan derivatives (Hyaff) implanted in rats. Biomaterials 1993, 14, 1154–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, C.; Sanginario, V.; Ambrosio, L.; di Silvio, L.; Santin, M. Chemical-physical characterization and in vitro preliminary biological assessment of hyaluronic acid benzyl ester-hydroxyapatite composite. J. Biomater. Appl. 2006, 20, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, M.; Yamaguchi, M.; Sumitomo, S.; Takai, Y. Hyaluronan-based biomaterials in tissue engineering. Acta Histochem. Cytochem. 2004, 37, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanginario, V.; Ginebra, M.; Tanner, K.; Planell, J.; Ambrosio, L. Biodegradable and semi-biodegradable composite hydrogels as bone substitutes: Morphology and mechanical characterization. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 17, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollinger, J.O.; Battistone, G.C. Biodegradable bone repair materials synthetic polymers and ceramics. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1986, 207, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.-K.; Wang, X.-L.; Wang, Y.-Z. Poly (p-dioxanone) and its copolymers. J. Macromol. Sci. Part C 2002, 42, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzin, A.; Ekenstein, V.; Alberda, G.; Zavaglia, C.; Ten Brinke, G.; Duek, E. Poly (para-dioxanone) and poly (l-lactic acid) blends: Thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties. J. Appl. Polymer Sci. 2003, 88, 2744–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Zhang, Z.p.; Li, Q.; Chen, D.L.; Chen, H.C.; Zhao, N.; Xiong, C.D. Miscibility, morphology and thermal properties of poly (para-dioxanone)/poly (d, l-lactide) blends. Polymer Int. 2009, 58, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, W.S. Principles of development and use of absorbable internal fixation. Tissue Eng. 2000, 6, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roller, M.B.; Li, Y.; Yuan, J.J. Implantable Medical Devices and Methods for Making Same. U.S. Patent 7,572,298, 11 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, D. Introduction to Biomaterials; World Scientific: Singapore, Singapore, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, W.; Chen, D.; Li, Q.; Chen, H.; Zhang, S.; Huang, X.; Xiong, C.-D. In vitro hydrolytic degradation of poly (para-dioxanone) with high molecular weight. J. Polym. Res. 2009, 16, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Zhang, L.-F.; Li, Q.; Chen, D.-L.; Xiong, C.-D. In vitro hydrolytic degradation of poly (para-dioxanone)/poly (d, l-lactide) blends. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2010, 122, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, I.M.; Sweeney, J. Mechanical Properties of Solid Polymers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schimming, R.; Schmelzeisen, R. Tissue-engineered bone for maxillary sinus augmentation. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2004, 62, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutmacher, D.W. Scaffolds in tissue engineering bone and cartilage. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 2529–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, P.K. Fiber-Reinforced Composites: Materials, Manufacturing, and Design; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mehboob, H.; Chang, S.-H. Application of composites to orthopedic prostheses for effective bone healing: A review. Compos. Struct. 2014, 118, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriano, K.P.; Daniels, A.; Heller, J. Biocompatibility and mechanical properties of a totally absorbable composite material for orthopaedic fixation devices. J. Appl. Biomater. 1992, 3, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, L.; Ahmed, I.; Felfel, R.; Qian, C. Finite element modelling of the flexural performance of resorbable phosphate glass fibre reinforced pla composite bone plates. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2012, 15, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, A.J.; Ahmed, I.; Haque, P.; Fitzpatrick, B.; Niazi, M.I.; Walker, G.S.; Rudd, C.D. Phosphate glass fibre composites for bone repair. J. Bionic Eng. 2009, 6, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, P.; Parsons, A.J.; Barker, I.A.; Ahmed, I.; Irvine, D.J.; Walker, G.S.; Rudd, C.D. Interfacial properties of phosphate glass fibres/PLA composites: Effect of the end functionalities of oligomeric pla coupling agents. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2010, 70, 1854–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Jones, I.; Parsons, A.; Bernard, J.; Farmer, J.; Scotchford, C.; Walker, G.; Rudd, C. Composites for bone repair: Phosphate glass fibre reinforced PLA with varying fibre architecture. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 22, 1825–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, G.; Zbib, A.; el-Ghannam, A.; Khraisheh, M.; Zbib, H. Characterization of a novel bioactive composite using advanced X-ray computed tomography. Compos. Struct. 2005, 71, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannillo, V.; Chiellini, F.; Fabbri, P.; Sola, A. Production of bioglass® 45s5-polycaprolactone composite scaffolds via salt-leaching. Compos. Struct. 2010, 92, 1823–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Parsons, A.; Palmer, G.; Knowles, J.; Walker, G.; Rudd, C. Weight loss, ion release and initial mechanical properties of a binary calcium phosphate glass fibre/PCL composite. Acta Biomater. 2008, 4, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felfel, R.M.; Ahmed, I.; Parsons, A.J.; Haque, P.; Walker, G.S.; Rudd, C.D. Investigation of crystallinity, molecular weight change, and mechanical properties of PLA/PBG bioresorbable composites as bone fracture fixation plates. J. Biomater. Appl. 2012, 26, 765–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, I.; Cronin, P.; Abou Neel, E.; Parsons, A.; Knowles, J.; Rudd, C. Retention of mechanical properties and cytocompatibility of a phosphate-based glass fiber/polylactic acid composite. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B 2009, 89, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felfel, R.; Ahmed, I.; Parsons, A.; Rudd, C. Bioresorbable screws reinforced with phosphate glass fibre: Manufacturing and mechanical property characterisation. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2013, 17, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felfel, R.; Ahmed, I.; Parsons, A.; Rudd, C. Bioresorbable composite screws manufactured via forging process: Pull-out, shear, flexural and degradation characteristics. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2013, 18, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felfel, R.; Ahmed, I.; Parsons, A.; Harper, L.; Rudd, C. Initial mechanical properties of phosphate-glass fibre-reinforced rods for use as resorbable intramedullary nails. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 47, 4884–4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.S.; Ahmed, I.; Parsons, A.J.; Rudd, C.D.; Walker, G.S.; Scotchford, C.A. Investigating the use of coupling agents to improve the interfacial properties between a resorbable phosphate glass and polylactic acid matrix. J. Biomater. Appl. 2012, 28, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felfel, R.; Ahmed, I.; Parsons, A.; Walker, G.; Rudd, C. In vitro degradation, flexural, compressive and shear properties of fully bioresorbable composite rods. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2011, 4, 1462–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hench, L.L. The story of bioglass®. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 17, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, Z.A.A.; Javaid, M.A.; Abdallah, M.N. Bone replacement graft materials in dentistry. In Dental Biomaterials (Principle and Its Application), 2nd ed.; Khurshid, S.Z., Ed.; Paramount Publishing Enterprise: Karachi, Pakistan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, Z.; Geffers, M.; Christel, T.; Barralet, J.E.; Gbureck, U. Chelate setting of alkali ion substituted calcium phosphates. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 10010–10017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Descamps, M.; Dejou, J.; Koubi, G.; Hardouin, P.; Lemaitre, J.; Proust, J.P. The biodegradation mechanism of calcium phosphate biomaterials in bone. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2002, 63, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radin, S.; Campbell, J.T.; Ducheyne, P.; Cuckler, J.M. Calcium phosphate ceramic coatings as carriers of vancomycin. Biomaterials 1997, 18, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogose, A.; Hotta, T.; Kawashima, H.; Kondo, N.; Gu, W.; Kamura, T.; Endo, N. Comparison of hydroxyapatite and beta tricalcium phosphate as bone substitutes after excision of bone tumors. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B 2005, 72, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daculsi, G.; LeGeros, R.; Heughebaert, M.; Barbieux, I. Formation of carbonate-apatite crystals after implantation of calcium phosphate ceramics. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1990, 46, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigaku, S.; Katsuyuki, F. Beta-tricalcium phosphate as a bone graft substitute. Jikeikai Med. J. 2005, 52, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hak, D.J. The use of osteoconductive bone graft substitutes in orthopaedic trauma. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2007, 15, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cameron, H.; Macnab, I.; Pilliar, R. Evaluation of a biodegradable ceramic. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1977, 11, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skorokhod, V.; Solonin, S.; Dubok, V.; Kolomiets, L.; Katashinskii, V.; Shinkaruk, A. Pressing and sintering of nanosized hydroxyapatite powders. Powder Metall. Metal Ceram. 2008, 47, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbe, E.; Marx, J.; Clineff, T.; Bellincampi, L. Potential of an ultraporous β-tricalcium phosphate synthetic cancellous bone void filler and bone marrow aspirate composite graft. Eur. Spine J. 2001, 10, S141–S146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ryu, H.S.; Lee, J.K.; Seo, J.H.; Kim, H.; Hong, K.S.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, D.H.; Chang, B.S.; Lee, C.K. Novel bioactive and biodegradable glass ceramics with high mechanical strength in the cao-SiO2-B2O3 system. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2004, 68, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.; Valerio, P.; Goes, A.; Leite, M.; Heneine, L.; Mansur, H. Biocompatibility evaluation of hydroxyapatite/collagen nanocomposites doped with Zn2+. Biomed. Mater. 2007, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irigaray, J.; Oudadesse, H.; Jallot, E.; Brun, V.; Weber, G.; Frayssinet, P. Materials in Clinical Applications; World Ceramics Congress and Forum on New Materials: Florence, Italy, 1999; pp. 399–403. [Google Scholar]

- Nurit, J.; Margerit, J.; Terol, A.; Boudeville, P. Ph-metric study of the setting reaction of monocalcium phosphate monohydrate/calcium oxide-based cements. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2002, 13, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, T.R.; Bhaduri, S.B.; Tas, A.C. A self-setting, monetite (CaHPO4) cement for skeletal repair. Adv. Bioceram. Biocompos. II 2007, 27, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Tamimi, F.; le Nihouannen, D.; Eimar, H.; Sheikh, Z.; Komarova, S.; Barralet, J. The effect of autoclaving on the physical and biological properties of dicalcium phosphate dihydrate bioceramics: Brushite vs. Monetite. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 3161–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohner, M.; Merkle, H.P.; Landuyt, P.V.; Trophardy, G.; Lemaitre, J. Effect of several additives and their admixtures on the physico-chemical properties of a calcium phosphate cement. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 1999, 11, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina, S.; Torres, P.M.; Goetz-Neunhoeffer, F.; Neubauer, J.; Ferreira, J.M.F. Newly developed Sr-substituted alpha-TCP bone cements. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilley, K.J.; Wright, A.J.; Farrar, D.; Barralet, J.E. Cement from nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite: Effect of sulphate ions. Bioceramics 2005, 284–286, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, F.T.; Torres, J.; Hamdan, M.; Rodriguez, C.R.; Cabarcos, E.L. Advantages of using glycolic acid as a retardant in a brushite forming cement. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2007, 83, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamimi, F.; Torres, J.; Kathan, C.; Baca, R.; Clemente, C.; Blanco, L.; Cabarcos, E.L. Bone regeneration in rabbit calvaria with novel monetite granules. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2008, 87, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aberg, J.; Brisby, H.; Henriksson, H.; Lindahl, A.; Thomsen, P.; Engqvist, H. Premixed acidic calcium phosphate cement: Characterization of strength and microstructure. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B 2010, 93, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryf, C.; Goldhahn, S.; Radziejowski, M.; Blauth, M.; Hanson, B. A new injectable brushite cement: First results in distal radius and proximal tibia fractures. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2009, 35, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, R.Q.; Byron, R.T.; Osborne, P.B.; West, K.P. PMMA: An essential material in medicine and dentistry. J. Long Term Effects Med. Implants 2005, 15, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, S.M.; Frondoza, C.G.; Lennox, D.W. Effects of polymethylmethacrylate exposure upon macrophages. J. Orthop. Res. 1988, 6, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stürup, J.; Nimb, L.; Kramhøft, M.; Jensen, J.S. Effects of polymerization heat and monomers from acrylic cement on canine bone. Acta Orthop. 1994, 65, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]