A Dominant Voice amidst Not Enough People: Analysing the Legitimacy of Mexico’s REDD+ Readiness Process

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Case Study and Methods

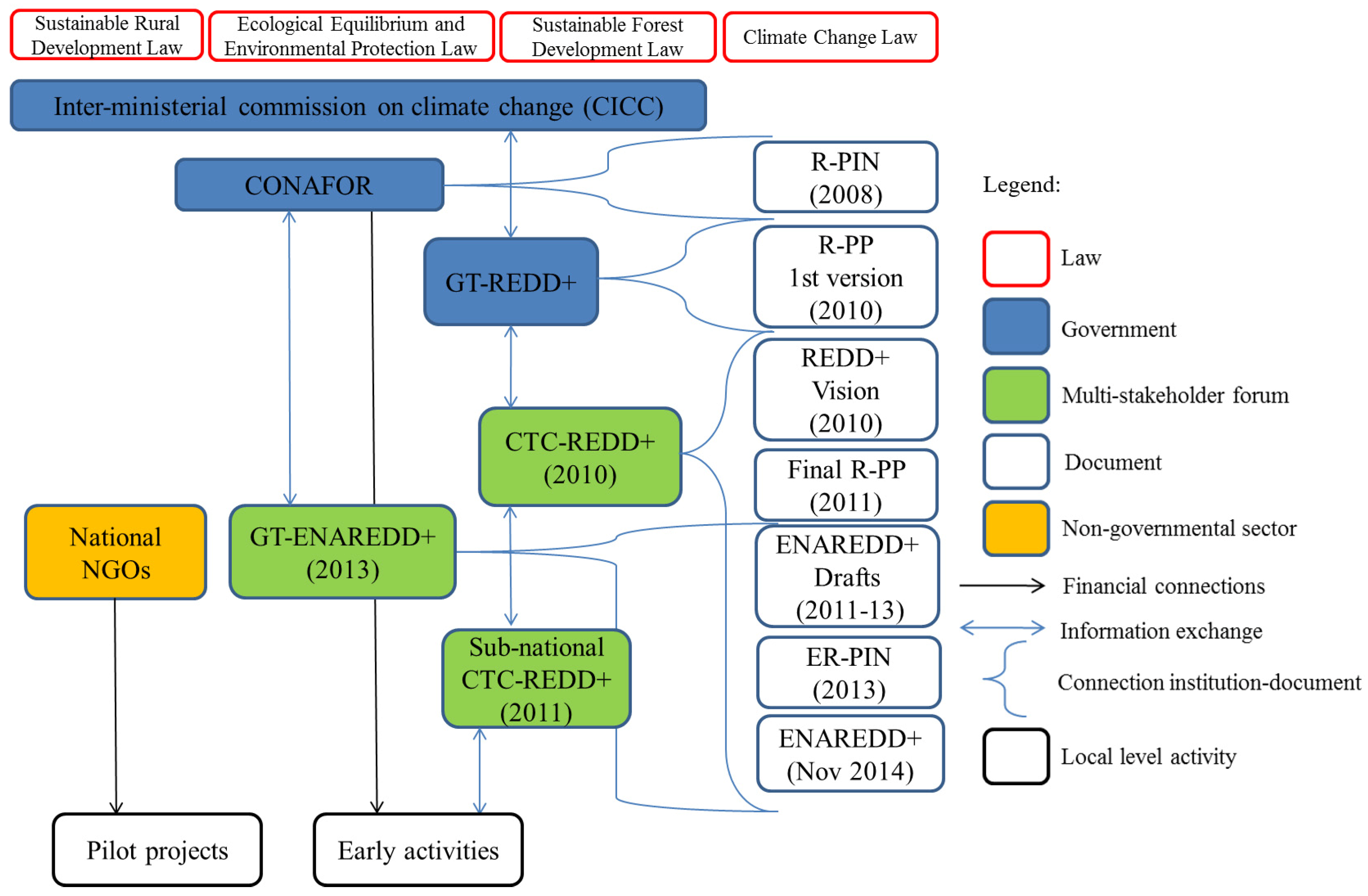

2.1. REDD+ Governance in Mexico

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Qualitative Content Analysis

2.3.2. Stakeholder Analysis

2.3.3. Discourse Analysis

3. Results

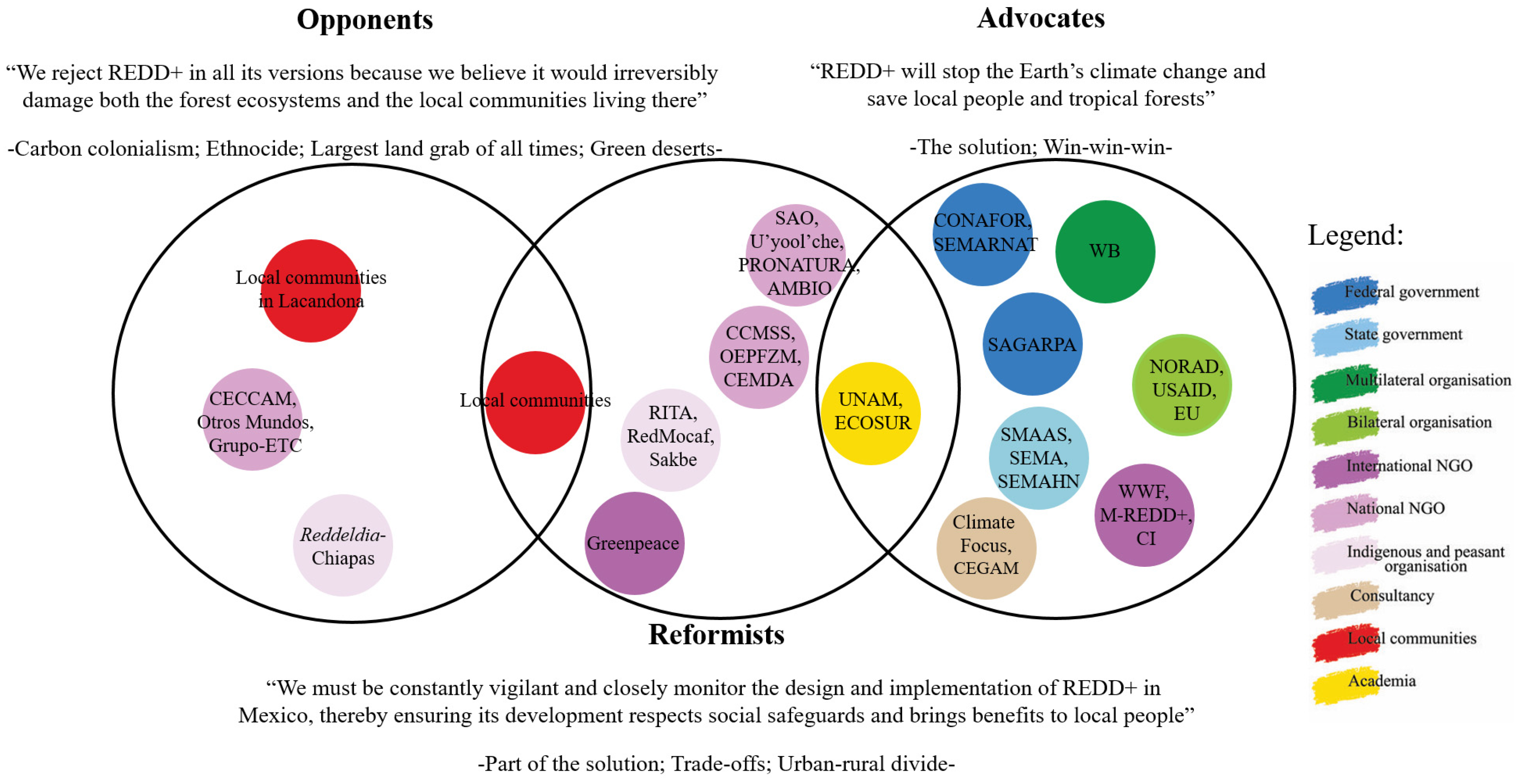

3.1. REDD+ Stakeholders

3.2. REDD+ Discourses

“They [the government] say to the communities: …we are fighting climate change, and we will pay you to help. Are you with us? The expected answer is: Of course we are.”(representative of Otros Mundos Chiapas in [76])

“Under the current legal framework, any change in land-use has to be authorised. Therefore if a person says: I will deforest; it is the same as if he says: I will kill three people, but if I instead kill only one, you have to compensate me.”(INECC officer, 05 February 2014)

“…if I take care of my forest but my neighbour gives his forest to a mining concession and therefore causes deforestation, the overall [carbon stock and emission reductions] measurements in a given territory will be affected. It is then a question of carbon ownership.”(RITA officer, 6 February 2014)

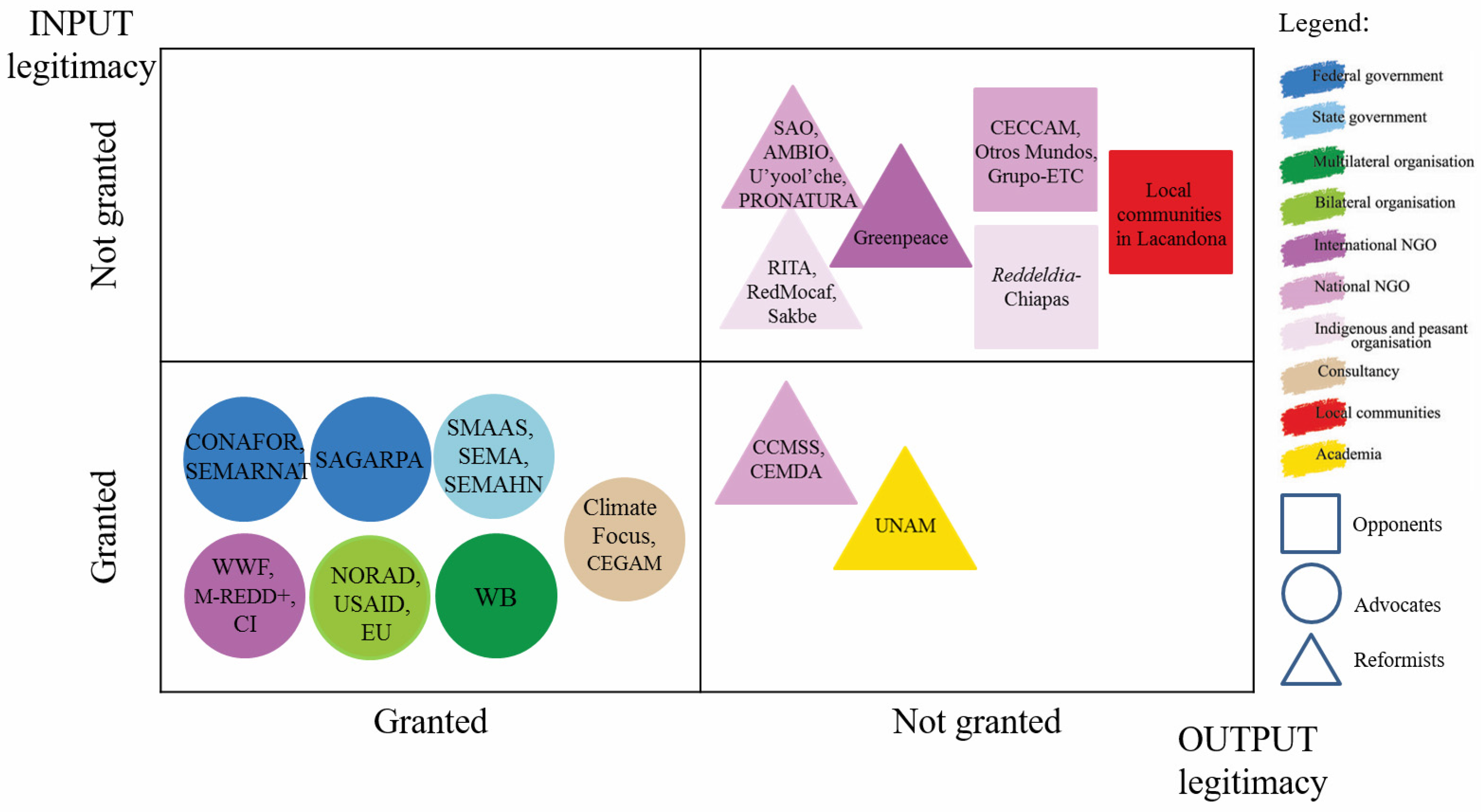

3.3. Degree of Discourse Influence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Corbera, E.; Schroeder, H. Governing and implementing REDD+. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.C.; Baruah, M.; Carr, E.R. Seeing REDD+ as a project of environmental governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, M. REDD+ governance. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2012, 3, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignola, R.; Guerra, L.; Trevejo, L.; Aymerich, J.P. REDD+ Governance across Scales in Latin America. Perceptions of the Opportunities and Challenges from the Model Forest Platform; REDD-Net Publications: London, UK, 2012; Available online: http://repositorio.bibliotecaorton.catie.ac.cr/bitstream/handle/11554/8285/REED_Governance_across_scales_in_Latin_America.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2016).

- Long, A. REDD+, Adaptation, and sustainable forest management: Toward effective polycentric global forest governance. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2013, 6, 384–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Plaza, C.; Visseren-Hamakers, I.J.; De Jong, W. The legitimacy of certification standards in climate change governance. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations Collaborative Programme on REDD+ (UN-REDD+). Programme Regions and Partner Countries. 2016. Available online: http://www.un-redd.org/partner-countries (accessed on 12 July 2016).

- Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) REDD+ Countries. 2016. Available online: https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/redd-countries-1 (accessed on 12 July 2016).

- Davis, C.; Nakhooda, S.; Daviet, F. Getting Ready. A Review of the World Bank Forest Carbon Partnership Facility Readiness Preparation Proposals, version 1.3; WRI Working Paper; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Available online: http://www.wri.org/gfi (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Bradley, A. Review of Cambodia’s REDD Readiness: Progress and Challenges, Forest and Conservation Project; Occasional Paper No. 4; Institute for Global Environmental Studies: Hayama, Japan, 2011; Available online: http://redd-database.iges.or.jp/redd/download/link?id=4 (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Nineteenth Session, Held in Warsaw from 11 to 23 November 2013. Available online: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2013/cop19/eng/10a01.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2016).

- Cadman, T.; Maraseni, T.N. The governance of REDD+: An institutional analysis in the Asia Pacific region and beyond. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2011, 55, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadman, T.; Maraseni, T.N. More equal than others? A comparative analysis of state and nonstate perceptions of interest representation and decisionmaking in REDD+ negotiations. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2013, 26, 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraseni, T.N.; Cadman, T. Comparative analysis of global stakeholders’ perceptions of the governance quality of the CDM and REDD+. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2015, 72, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Document FCCC/CP/2010/7/Add.1, Report of the Conference of the Parties Fifteenth Session, Held in Copenhagen from 7 to 19 December 2009. Available online: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2010/cop16/eng/07a01.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2016).

- Lyster, R. REDD+, transparency, participation and resource rights: The role of law. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Collaborative Programme on REDD+ (UN-REDD+). Legal Analysis of Cross-Cutting Issues for REDD+ Implementation. Lessons Learned from Mexico, Viet Nam and Zambia, 2013. UN-REDD Programme Secretariat International Environment House: Geneva, Switzerland. Available online: http://theredddesk.org/sites/default/files/resources/pdf/2013/legal-analysis-final-web_1.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2016).

- Cadman, T.; Maraseni, T.; López-Casero, F.; Ok Ma, H. Governance values in the climate change regime: Stakeholder perceptions of REDD+ legitimacy at the national level. Forests 2016, 7, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharpf, F. Governing in Europe. Effective and Democratic; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckstrand, K. Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainable development: Rethinking legitimacy, accountability and effectiveness. Eur. Environ. 2006, 16, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavola, J. Institutions and environmental governance: A reconceptualization. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 63, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatn, A.; Vedeld, P. National governance structures for REDD+. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, D.; Mayer, C. Making Sustainable Development a Reality: The Role of Social and Ecological Standards; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit: Kessel, Germany, 2003; p. 50. Available online: http://www.mekonginfo.org/assets/midocs/0002193-economy-making-sustainable-development-a-reality-the-role-of-social-and-ecological-standards.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Parkinson, J. Deliberating in the Real World: Problems of Legitimacy in Deliberative Democracy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vatn, A. Environmental Governance—A Conceptualization. In The Political Economy of Environment and Development in a Globalized World. Exploring the Frontiers; Kjosavik, D., Vedeld, P., Eds.; Tapir Academic Press: Trondheim, Norway, 2011; pp. 131–152. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The Cancun Agreements. 2010. Available online: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2010/cop16/eng/07a01.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Angelsen, A. Moving ahead with REDD: Issues, Options and Implications; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2008; Available online: http://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/Books/BAngelsen0801.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Veierland, K. Inclusive REDD+ in Indonesia? A Study of the Participation of Indigenous People in the Making of the National REDD+ Strategy in Indonesia; University of Oslo: Oslo, Norway, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Angelsen, A.; Brockhaus, M.; Sunderlin, W.D.; Verchot, L.V. Analysing REDD+: Challenges and Choices; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2012; Available online: http://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/Books/BAngelsen1201.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Aquino, A.; Guay, B. Implementing REDD+ in the Democratic Republic of Congo: An analysis of the emerging national REDD+ governance structure. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 36, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyika, K.F.K.; Kajembe, G.C.; Silayo, D.A.; Vatn, A. Strategic power and power struggles in the national REDD+ governance process in Tanzania: Any effect on its legitimacy? Tanzan. J. For. Nat. Conserv. 2013, 83, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mulyani, M.; Jepson, P.R. REDD+ and forest governance in Indonesia: A multistakeholder study of perceived challenges and opportunities. J. Environ. Dev. 2013, 22, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somorin, O.A.; Visseren-Hamakers, I.J.; Arts, B.; Sonwa, D.J.; Tiani, A.-M. REDD+ policy strategy in Cameroon: Actors, institutions and governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 35, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelli, F.; Erler, D.; Frank, S.; Hein, J.I.; Hotz, H.; Cruz-Melgarejo, A.M.S. Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) in Peru: A Challenge to Social Inclusion and Multi-Level Governance; German Development Institute: Bonn, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Minang, P.A.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Duguma, L.A.; Alemagi, D.; Do, T.H.; Bernard, F.; Agung, P.; Robiglio, V.; Catacutan, D.; Suyanto, S.; et al. REDD+ Readiness progress across countries: Time for reconsideration. Clim. Policy 2014, 14, 685–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttrell, C.; Resosudarmo, I.A.P.; Muharrom, E.; Brockhaus, M.; Seymour, F. The political context of REDD+ in Indonesia: Constituencies for change. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 35, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, D.B.; Pham, T.T.; Di Gregorio, M.; Karki, R.; Paudel, N.S.; Brockhaus, M.; Bhushal, R. REDD+ politics in the media: A case from Nepal. Clim. Chang. 2016, 138, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF). Readiness Plan Idea Note (R-PIN)—External Review Form, Mexico. 2008. Available online: https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/sites/forestcarbonpartnership.org/files/Mexico_TAP_Consolidated.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Comisió Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). The Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) Readiness Plan Idea Note (R-PIN) Mexico. 2008. Available online: https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/sites/forestcarbonpartnership.org/files/Mexico_FCPF_R-PIN.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). The Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF). Readiness Preparation Proposal (R-PP) Mexico. 2010. Available online: http://forestcarbonpartnership.org/sites/fcp/files/Documents/tagged/Mexico_120211_R-PP_Template_with_disclaimer.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). Visión de México Sobre REDD+. Hacia una Estrategia Nacional. 2010. Available online: http://www.conafor.gob.mx:8080/documentos/docs/35/2521Visi%C3%B3n%20de%20M%C3%A9xico%20para%20REDD_.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- U’yool’che and Servicios Ecosistémicos de la Selva Maya S.C. Plan Vivo Project Design Document (PDD), Much Kanan K’aax; U’yool’che and Servicios Ecosistémicos de la Selva Maya S.C.: Felipe Carrillo Puerto, Mexico, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Civil Mexicano para la Silvicultura Sostenible (CCMSS). Nota de Idea del Proyecto REDD+ Comunitario en la Zona Maya de José María Morelos, Quintana Roo. 2011. Available online: http://www.ccmss.org.mx/descargas/pin_jmm_140711.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- PRONATURA. El Zapotal. 2015. Available online: http://www.pronatura-ppy.org.mx/seccion.php?id=5 (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). Estrategia Nacional para REDD+ (ENAREDD+). Primer borrador. 2011. Available online: http://www.conafor.gob.mx:8080/documentos/docs/35/4859Elementos%20para%20el%20dise%C3%B1o%20de%20la%20Estrategia%20Nacional%20para%20REDD_.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). Participación. CTC-REDD+ Estatales. 2015. Available online: http://www.conafor.gob.mx/web/temas-forestales/bycc/redd-en-mexico/participacion/ (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Ley General de Desarrollo Forestal Sustentable (LGDFS). El Diario Oficial de la Federación el 25 de Febrero de 2003 (Última Reforma DOF 04-06-2012); Cámara de Diputados del H. Congreso de la Unión, Secretaría General, Secretaría de Servicios Parlamentarios: Mexico city, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ley General del Equilibrio Ecológico y la Protección al Ambiente (LGEEPA). El Diario Oficial de la Federación el 28 de enero de 1988 (Última Reforma DOF 04-06-2012); Cámara de Diputados del H. Congreso de la Unión, Secretaría General, Secretaría de Servicios Parlamentarios: Mexico city, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Nacional Forestal (CONAF). Memoria de Gestión de la Renovación del Consejo Nacional Forestal para el Periodo 2013–2014. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/82979/Memoria_de_Gestion_CONAF_2013_-2014.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Jagger, P.; Brockhaus, M.; Duchelle, A.E.; Gebara, M.F.; Lawlor, K.; Resosudarmo, I.A.P.; Sunderlin, W.D. Multi-level policy dialogues, processes, and actions: Challenges and opportunities for national REDD+ safeguards measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV). Forests 2014, 5, 2136–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). Estrategia Nacional Para REDD+ (ENAREDD+). Borrador Octubre de 2012. Available online: http://www.conafor.gob.mx:8080/documentos/docs/35/5303Elementos%20para%20el%20dise%C3%B1o%20de%20la%20Estrategia%20Nacional%20para%20REDD_.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). Estrategia Nacional Para REDD+ (ENAREDD+). Borrador Julio de 2013. Available online: http://www.conafor.gob.mx:8080/documentos/docs/35/4861Estrategia%20Nacional%20para%20REDD_.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). Estrategia Nacional Para REDD+ (ENAREDD+). Borrador Abril de 2014. Available online: http://www.conafor.gob.mx:8080/documentos/docs/35/5559Elementos%20para%20el%20dise%C3%B1o%20de%20la%20Estrategia%20Nacional%20para%20REDD_.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). Estrategia Nacional Para REDD+ (ENAREDD+) (Para Consulta Pública). Available online: http://www.conafor.gob.mx:8080/documentos/docs/35/6462Estrategia%20Nacional%20para%20REDD_%20(para%20consulta%20p%C3%BAblica)%202015.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) Carbon Fund. Emission Reductions Program. Idea Note (ER-PIN) Mexico. Available online: http://www.conafor.gob.mx:8080/documentos/docs/4/6170Propuesta%20de%20Nota%20de%20Idea%20de%20la%20Iniciativa%20de%20Reducci%C3%B3n%20de%20Emisiones%20%28ERPIN%29%20de%20M%C3%A9xico.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF). ER-PIN Template. 2013. Available online: http://www.bankinformationcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/FCPF-Carbon-Fund-ER-PIN-v4.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Beardsworth, A.; Keil, T. The vegetarian option: Varieties, conversions, motives, and careers. Sociol. Rev. 1992, 40, 253–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 4th ed.; Altamira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 186–210. [Google Scholar]

- Angelsen, A.; Bockhaus, M.; Kanninen, M.; Sills, E.; Sunderlin, W.D.; Wertz-Kanounnikoff, S. Realising REDD+: National Strategy and Policy Options; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2009; Available online: http://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/Books/BAngelsen0902.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2016).

- Mayers, J. Stakeholder Power Analysis; International Institute for and Environment Development (IIED): London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Diefenbach, T.; Sillince, J.A.A. Formal and informal hierarchy in different types of organization. Organ. Stud. 2011, 32, 1515–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overseas Development Administration. Guidance Note on How to Do Stakeholder Analysis of Aid Projects and Programmes; Overseas Development Department: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, J. Legitimacy problems in deliberative democracy. Polit. Stud. 2003, 51, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M.A. Discourse coalitions and the institutionalisation of practice: The case of acid rain in Great Britain. In The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning; Fischer, F., Forester, J., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham/London, UK, 1993; pp. 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dryzek, J. The Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N.; Benjaminsen, T.A.; Brown, K.; Svarstad, H. Advancing a political ecology of global environmental discourses. Dev. Chang. 2001, 32, 681–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashore, B. Legitimacy and the privatization of environmental governance: How Non State Market-Driven (NSMD) governance systems gain rule making authority. Governance 2002, 15, 503–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffek, J. The legitimation of international governance: A discourse approach. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 2003, 9, 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffek, J. Discursive legitimation in environmental governance. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffek, J.; Hahn, K. Evaluating Transnational NGOs: Legitimacy, Accountability, Representation; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, A.; Keohane, R.O. The legitimacy of global governance institutions. Ethics Int. Aff. 2006, 20, 405–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M.A. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 9–44. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Evaluaciones de la OCDE Sobre el Desempeño Ambiental: México 2013; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Evaluación de los Recursos Forestales Mundales, Informe Nacional, México; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010; Available online: http://www.fao.org/forestry/20262-1-176.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- De Ita, A. Land concentration in Mexico after PROCEDE. In Promised Land: Competing Visions of Agrarian Reform; Rosset, P.M., Patel, R., Courville, M., Eds.; Institute for Food and Development Policy: Oakland, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Conant, J. A Broken Bridge to the Jungle: The California-Chiapas Climate Agreement Opens Old Wounds; Global Justice Ecology Project. Climate Connections. 7 April 2011. Available online: http://climate-connections.org/2011/04/07/a-broken-bridge-to-the-jungle-the-california-chiapas-climate-agreement-opens-old-wounds/ (accessed on 31 August 2016).

- Lang, C. People’s Forum Against REDD+ in Chiapas, Mexico. Redd-Monitor. 24 September 2012. Available online: http://www.redd-monitor.org/2012/09/24/peoples-forum-against-redd-in-chiapas-mexico/ (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Papel Revolución. Comunicado REDDeldía Leido en el Foro de Gobernadores pro REDD+. Papel Revolución. 27 September 2012. Available online: http://www.papelrevolucion.com/2012/09/comunicado-reddeldia-leido-en-el-foro.html (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Reddeldia. Open letter from Chiapas about the Agreement between the States of Chiapas (Mexico), Acre (Brazil) and California (USA). Reddeldia. April 2013. Available online: http://reddeldia.blogspot.rs/2013/04/carta-abierta-de-chiapas-sobre-el.html (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Otros Mundos AC- Friends of the Earth Mexico. REDD: la codicia por los árboles (El Caso Chiapas: la Selva Lacandona al mejor postor). Otros Mundos AC, Friends of the Earth Mexico. 2011. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b0Md6WXj0pM (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Centro de Estudios Para el Cambio en el Campo Mexicano (CECCAM). REDD+ y los territorios indígenas y campesinos; CECCAM: Mexico city, Mexico, 2012; Available online: http://ceccam.org/sites/default/files/AAA-REDD%2BWeb.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Phelps, J.; Edward, L.W.; Agrawal, A. Does REDD+ threaten to recentralize forest governance? Policy Forum 2010, 328, 312–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biermann, F.; Betsill, M.M.; Gupta, J.; Kanie, N.; Lebe, L.; Liverman, D.; Schroeder, H.; Siebenhüner, B. Earth System Governance: People, Places and the Planet. Science and Implementation Plan of the Earth System Governance Project; Earth System Governance Report 1, IHDP Report 20; The Earth System Governance Project: Bonn, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Corbera, E.; Estrada, M.; May, P.; Navarro, G.; Pacheco, P. Rights to land, forests and carbon in REDD+: Insights from Mexico, Brazil and Costa Rica. Forests 2011, 2, 301–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjar, R.; Kozlak, A.R.; Inners, J.L. Is decentralization leading to “real” decision-making power for forest dependent communities? Case studies from Mexico and Brazil. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosie, T.; Herbst, T. Using Stakeholder Processes in Environmental Decision Making: An Evaluation of Lessons Learned, Key Issues, and Future Challenges; Ruder Finn Washington: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Forest Peoples Programme, Civil Society Groups in DRC Suspend Engagement with National REDD Coordination Process. Available online: http://www.forestpeoples.org/topics/redd-and-related-initiatives/news/2012/07/civil-society-groups-drc-suspend-engagement-nationa (accessed on 6 November 2016).

- Lang, C. COONAPIP, Panama’s Indigenous Peoples Coordinating Body, Withdraws from UN-REDD. REDD-Monitor, 2013. Available online: http://www.redd-monitor.org/2013/03/06/coonapip-panamas-indigenous-peoples-coordinating-body-withdraws-from-un-redd/ (accessed on 6 November 2016).

- Hatanaka, M.; Konefal, F. Legitimacy and standard development in multi-stakeholder initiatives: A case study of the leonardo academy’s sustainable agriculture standard initiative. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 2012, 20, 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- Boström, M.; Tamm Hallström, K. Global multi-stakeholder standard setters: How fragile are they? J. Glob. Ethics 2013, 9, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, P.H.; Millikan, B.; Gebara, M.F. The Context of REDD+ in Brazil: Drivers, Agents and Institutions; Occasional Paper 55, revised edition; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rantala, S.; Di Gregorio, M. Multistakeholder environmental governance in action: REDD+ discourse coalitions in Tanzania. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, J.; Naess, L.O.; Newsham, A.; Sitoe, A.; Fernandez, M.C. Carbon Forestry and Climate Compatible Development in Mozambique: A Political Economy Analysis; IDS Working Paper No. 448; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Di Gregorio, M.; Brockhaus, M.; Cronin, T.; Muharrom, E.; Santoso, L.; Mardiah, S.; Büdenbender, M. Equity and REDD+ in the Media: A comparative analysis of policy discourses. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boedeltje, M.; Cornips, J. Input and Output Legitimacy in Interactive Governance. NIG Annual Work Conference, Rotterdam (No. NIG2-01) 2004. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1765/1750 (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Hemmati, M. Multi-Stakeholder Processes for Governance and Sustainability beyond Deadlock and Conflict; Earthscan Publications Ltd.: London, UK; Sterling, VA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vijge, M.J.; Brockhaus, M.; Di Gregorio, M.; Muharrom, E. Framing REDD+ in the national political arena: A comparative discourse analysis of Cameroon, Indonesia, Nepal, PNG, Vietnam, Peru and Tanzania. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 39, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushley, R.B. REDD+ policy making in Nepal: Toward state-centric, polycentric, or market-oriented governance? Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushley, B.R.; Khatri, D.B. REDD+: Reversing, Reinforcing or Reconfiguring Decentralized Forest Governance in Nepal; Discussion Paper Series 11:3; Forest Action Nepal: Patan, Nepal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bastakoti, R.R.; Davidsen, C. Nepal’s REDD+ readiness preparation and multi-stakeholder consultation challenges. J. For. Livelihood 2015, 13, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | High | Moderate | Low | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attributes | ||||

| Relevance | Actors who design or implement public policies and activities that directly contribute to land-use change, either increasing or decreasing carbon stocks | Actors who provide financial resources and/or information for the development of specific land-use change activities that either increase or decrease carbon stocks | Actors whose activities do not have an impact (or whose impact would be hard to prove) on land-use change | |

| Influence | Actors who are primary recipients of relevant financial resources for REDD+ or who can directly influence policies given their position in formal social hierarchies | Actors receiving REDD+ financial resources from government, thus steering REDD+ design in ways that meet their expectations | Actors who do not hold significant financial REDD+ resources and who are not present in formal REDD+ decision-making forums | |

| Interest | Actors who financially invest in REDD+ and/or regularly participate in either the governmental or alternative REDD+ forums, contributing to discussions in oral and/or written forms | Actors with all preconditions to participate (e.g., financial resources, invited to meetings) but who only intermittently participate in the governmental or alternative REDD+ oral or written discussions | Actors who were formally invited to participate in either the governmental or alternative REDD+ forums, but neither participated nor communicated their views on REDD+ | |

| Conceptual Dimensions | All Storylines (3) | Less Than Three Storylines (2 or less) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategic Dimensions | |||

| Four or more storylines (4–7) | Dominant | Marginalised | |

| Less than four storylines (0–3) | Marginalised | Marginalised | |

| Input Legitimacy | Granted | Not Granted | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Output Legitimacy | |||

| Granted | Actors who perceive the CTC as a legitimate forum and share a ‘dominant’ discourse | Actors who perceive the CTC as an illegitimate forum and share a ‘dominant’ discourse | |

| Not granted | Actors who perceive the CTC as a legitimate forum and share a ‘marginalised’ discourse | Actors who perceive the CTC as an illegitimate forum and share a ‘marginalised’ discourse | |

| Key REDD+ Issues | Official REDD+ Statements |

|---|---|

| REDD+ goals and role | Deforestation is the third largest source of carbon emissions in the country and worldwide [54] (pp. 11, 20). Any disturbance of tropical forests significantly affects the global carbon cycle and contributes to climate change [54] (p. 12). Mexico has a great potential for REDD+ not only for reducing deforestation and forest degradation, but also for increasing forest carbon stocks [54] (p. 22). |

| Deforestation drivers | The main drivers of deforestation in the country are unsound agricultural policies followed by tourism, urban and industrial development; lack of coordination across these land-use sectors, and ineffective legislation [54] (p. 20); [55] (p. 28). Forest owners have few incentives to preserve them due to the market demand for specific products (e.g., timber, minerals, food, meat, biofuels, etc.), local needs, and population growth [55] (p. 27). |

| Local people and deforestation | Greater deforestation occurs in communities without forest management institutions [55] (p. 28). Forest degradation is caused by local forest users’ activities (e.g., selective harvesting, overgrazing, extraction of firewood, etc.) [55] (p. 26). |

| Implementation scale | The FCPF Carbon Fund pays for emission reductions to the National Fund, which transmits the sum (proportionally according to emissions reduction contribution) to a jurisdictional fund (state or interstate fund) [54] (p. 46); [55] (pp. 34, 64). |

| Benefit-sharing strategy | The scale of activities under REDD+ corresponds to a territory that includes a number of communities and obeys environmental limits (basin, sub-basin, biological corridor) [55] (p. 33). |

| Scope of activities | Sustainable rural development is the best way to realise REDD+ in Mexico [54] (pp. 26, 33). PES is one of the activities within the special programmes [55] (pp. 31–33). REDD+ offers new opportunities to effective management and expansion of protected areas to contribute to climate change mitigation [54] (p. 25). Community forest management can be more effective in controlling deforestation than protected areas [55] (pp. 31–33). Sustainable agricultural practices could be part of REDD+ [55] (p. 33). |

| Co-benefits | Co-benefits or collateral benefits refer to the additional benefits to carbon storage resulting from REDD+ implementation, such as poverty reduction, biodiversity conservation and improvement in forest governance [54] (p. 86). REDD+ in Mexico will generate substantial non-carbon benefits because it will be implemented in early action regions [55] (pp. 2, 30, 63). |

| Social safeguards | Safeguards are designed to prevent and mitigate any direct or indirect negative impact on ecosystems and local people [54] (pp. 67–68). REDD+ is of voluntary nature and a collective consent by community authorities will guarantee respect of social safeguards [55] (p. 80). Safeguard Information System and Safeguard National System should oversee safeguards implementation and respect [54] (p. 70); [55] (p. 14). |

| Land tenure | Mexico has a sound community land rights system, therefore there is little risk of land rights violations [55] (p. 36). |

| Carbon rights | The ownership over biomass and carbon stocks is in the hands of forest owners, as sanctioned by national legislation (Art. 134bis, General Law of Sustainable Forest Development). However, it is not legally or technically feasible to attribute emissions reductions that result from avoided deforestation to a particular forest owner within the landscape, who might only hold the rights [not the ownership] to benefit from these emissions reduction [54] (p. 35); [55] (p. 36). Avoided deforestation has not been defined as an environmental service in any legislation to date. If necessary, corresponding law reforms should be promoted [54] (p. 35). |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Špirić, J.; Corbera, E.; Reyes-García, V.; Porter-Bolland, L. A Dominant Voice amidst Not Enough People: Analysing the Legitimacy of Mexico’s REDD+ Readiness Process. Forests 2016, 7, 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/f7120313

Špirić J, Corbera E, Reyes-García V, Porter-Bolland L. A Dominant Voice amidst Not Enough People: Analysing the Legitimacy of Mexico’s REDD+ Readiness Process. Forests. 2016; 7(12):313. https://doi.org/10.3390/f7120313

Chicago/Turabian StyleŠpirić, Jovanka, Esteve Corbera, Victoria Reyes-García, and Luciana Porter-Bolland. 2016. "A Dominant Voice amidst Not Enough People: Analysing the Legitimacy of Mexico’s REDD+ Readiness Process" Forests 7, no. 12: 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/f7120313